Abstract

There is a significant gap in our knowledge of the microbe–host relationship between urban and traditional rural populations. We conducted a large-scale study to examine the gut microbiota of different traditional rural and urban lifestyles in human populations. Using high-throughput 16S ribosomal RNA gene amplicon sequencing, we tested urban French, Saudi, Senegalese, Nigerian and Polynesian individuals as well as individuals living in traditional rural societies, including Amazonians from French Guiana, Congolese Pygmies, Saudi Bedouins and Algerian Tuaregs. The gut microbiota from individuals living in traditional rural settings clustered differently and presented significantly higher diversity than those of urban populations (p 0.01). The bacterial taxa identified by class analysis as contributing most significantly to each cluster were Phascolarctobacterium for traditional rural individuals and Bifidobacterium for urban individuals. Spirochaetae were only present in the gut microbiota of individuals from traditional rural societies, and the gut microbiota of all traditional rural populations was enriched with Treponema succinifaciens. Cross-transmission of Treponema from termites or swine to humans or the increased use of antibiotics in nontraditional populations may explain why Treponema is present only in the gut microbiota of traditional rural populations.

Keywords: Geography, gut microbiota, metagenomics, probiotics, traditional living, treponema

Introduction

Sequencing surveys of the human intestinal microbiota have revealed differences in the gut microbiota between people of different origins, indicating that geography may be an important factor affecting the gut microbiota [1], [2], [3], [4]. Studies between unindustrialized rural communities from Africa and South America and industrialized Western communities from Europe and North America have revealed specific gut microbiota adaptations to their respective lifestyles [4]. Nonindustrialized rural societies are the target for understanding trends in human gut microbiota interactions, as they use fewer antibiotics and often consume a greater diversity of seasonally available, unrefined foods [5]. Dietary habits are considered to be one of the main factors contributing to the diversity and composition of human gut microbiota because dietary fermentable fibre or fat content changes its composition [6].

It is not yet fully understood how the different environments and wide range of diets that modern humans follow around the world has affected the microbial ecology of the human gut. Exposure to the large variety of environmental microbes associated with a high-fibre diet may increase potentially beneficial bacterial genomes, enriching the gut microbiota. A reduction in microbial richness may be one of the undesirable effects of globalization. Few studies have focused on the gut microbiota of individuals from traditional rural communities [1], [2], [7], [8]. Moreover, all these studies were based on the comparison of a few traditional communities and a small number of individuals. On the basis of these studies, it appears that Spirochaetes have only been observed in the gut microbiota of traditional rural human populations with non-Westernized lifestyles [7], [8].

Despite the recent focus on traditional rural societies, there remains a significant gap in our knowledge of the microbe–host relationship between urban and traditional rural populations. As a result of the cultural, behavioral and ecological environment, we hypothesized that traditional rural populations harbour different gut microbiota profiles than those living in urban or rural environments. Our aim was to compare the gut microbiota between these two populations in order to enable us to understand how the human microbiota adjusts with a foraging lifestyle. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a large-scale study testing the gut microbiota of different traditional rural and urban lifestyles in various human populations using high-throughput 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene amplicon sequencing.

Patients and methods

Subject selection criteria

We tested urban and semiurban adult volunteers from France, Saudi Arabia, French Polynesia, French Guyana, Nigeria and Senegal. In addition, we tested adult volunteers living traditional rural lifestyles, including Bedouins from Saudi Arabia, Tuaregs from southern Algeria, an Amazonian population living in the village of Trois-Sauts and Pygmies living in the villages of Thanry-Ipendja, Pokola and Bene-Gamboma in Congo. The exclusion criteria were individuals under the age of 18; those with a history of colon cancer, inflammatory bowel disease and acute or chronic diarrhea in the previous 8 weeks; and treatment with an antibiotic in the 2 months before faecal sampling. Stool samples were collected under aseptic conditions using clean, dry, screw-top containers and were immediately stored at −20°C.

This study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the King Abdul Aziz University under agreement number 014-CEGMR-2-ETH-P and by the ethics committee of the Institut Fédératif de Recherche IFR48, Faculty of Medicine, Marseille, France. The agreement of the ethics committee of the IFR48 (Marseille, France) was obtained under reference 09-022 and the agreement of the ethics committee of the Institute Louis Malardé was obtained under reference 67-CEPF. Agreement was also obtained from the Ministry for Health of the Republic of Congo (000208/MSP/CAB.15 du Ministère de la Santé et de la Population, 20 August 2015).

All methods in this study were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. Informed consent forms were provided to all participants and were obtained at the time of sample collection. For the Pygmies and Tuaregs, all permissions were granted orally, as the participants were illiterate. The representatives of a local health centre and the village elders accompanied the researchers to ensure that information was correctly translated into local languages and that the villagers were willing to take part in the study.

Extraction of DNA from stool samples and 16S rRNA sequencing using MiSeq technology

Faecal DNA was extracted from samples using the NucleoSpin Tissue Mini Kit (Macherey Nagel, Hoerdt, France) according to a previously described protocol [9]. Samples were sequenced for 16S rRNA using MiSeq technology as previously described [8], [10].

Data processing: filtering the reads, dereplication and clustering

Paired-end fastq files were assembled using FLASH [11]. A total of 7 518 258 joined reads were filtered, then analysed in QIIME by choosing Chimeraslayer for removing chimera and Uclust [11], [12] for operational taxonomic unit (OTU) extraction as described in [8], [10]. Extracted OTUs were blasted [13] against the Silva SSU and LSU database [14] of release, and taxonomy was assigned with majority voting [15], [16].

Database of obligate anaerobes

We conducted a bacterial oxygen tolerance database based on the literature (http://www.mediterranee-infection.com/article.php?laref=374). Each phylotype was defined as obligate anaerobe, aerotolerant or unknown, depending on oxygen tolerance.

Statistical analysis

The richness and biodiversity index was calculated using QIIME [11]. Richness was measured using the Chao1 index and diversity (how uniformly sequences are spread in different OTUs) was measured using the nonparametric Shannon formula. Nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney analyses were performed to identify significantly different bacterial taxa among the study participants. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed in QIIME [11] by rarefying 10 000 sequences for each sample and using weighted unifrac [11] distances. We also performed an Adonis [17] test using the weighted unifrac distance. Linear discriminant analysis was performed using LEfse [18] with a normalized option. The Jensen-Shannon distance of genus abundance was used for clustering [19], the Calinski-Harabasz index [20] was used to assess the optimal number of clusters and the Silhouette coefficient [21] was used for cluster validation. PCoA and between-class analysis were performed, and the results were plotted [19]. Other statistical analyses were performed by SPSS 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) [11].

Results

We tested 177 volunteers living in urban and semiurban societies, including 59 individuals from France [22], [23], 18 from Saudi Arabia [23], 70 from Senegal [24], 17 from Nigeria [24] and 13 from Polynesia. In addition, we tested 222 volunteers living in traditional rural societies, including 37 Amazonians, 127 Pygmies, 11 Bedouins [23] and 47 Tuaregs (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Composition of gut microbiota

The analysis of the high-quality reads revealed that the predominant phyla in the gut microbiota of all individuals contained sequences mostly belonging to Firmicutes, followed by Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2). No significant difference was found in the relative abundance of Firmicutes among the populations. However, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria was significantly lower in the gut microbiota of Saudis and Bedouins compared to the other populations tested (p 0.002 and p 0.005, respectively). Moreover, the relative abundance of Actinobacteria was significantly lower in the gut microbiota of Pygmies, Amazonians, Tuaregs and Nigerians (p 0.0005, p 0.0007, p 0.008 and p 0.01 respectively). The relative abundance of Bacteroidetes was significant lower in the gut microbiota of Bedouins, Saudis and Senegalese (p 0.0008, p 0.009 and p 0.02 respectively). Spirochaetae existed only in the gut microbiota of Amazonians, Pygmies, Bedouins and Tuaregs, whereas Fibrobacteres existed only in Amazonians and Pygmies.

Table 1.

Differences between urban and traditional rural populations

| Characteristic | Traditional rural | Urban |

|---|---|---|

| No. of different phyla | 19 | 21 |

| Significantly enriched phyla |

|

|

| Unique phyla |

|

None |

| No. of genera | 1748 | 918 |

| No. of unique genera | 1093 | 263 |

| Most abundant genera |

|

|

When we compared the gut microbiota of individuals living in urban societies to those living in traditional rural societies, we found no significant difference in the relative abundance of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria, whereas urban societies presented significantly higher Actinobacteria (p 0.03) and significantly lower Bacteroidetes (p 0.01). In addition, the relative abundance of Elusimicrobia, Tenericutes, Fusobacteria, Lentisphaerae, Cyanobacteria and Acidobacteria was significantly higher in the gut microbiota of traditional rural societies (p < 0.05), whereas Synergistetes, Chlamydiae, Verrucomicrobia and Saccharibacteria were significantly higher in the gut microbiota of those living in urban societies (p < 0.05). Finally, Spirochaetae, Fibrobacteres and Latescibacteria were present only in the gut microbiota of those living in traditional rural societies.

Urban individuals presented 918 different genera and traditional rural individuals 1748 different genera in their gut microbiota (Supplementary Fig. 3). All participants shared a core set of bacterial genera that was recovered from a majority of individuals in every sampled population. We detected 614 genera in >50% of traditional rural individuals and 584 genera in >50% of urban individuals (Supplementary Fig. 4). A linear discriminant analysis score of >2.0 revealed that Prevotella, Succinivibrio and Faecalibacterium were more abundant in the gut microbiota of traditional rural individuals, whereas Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus and Lactobacillus genera were more abundant in the gut microbiota of urban individuals (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6).

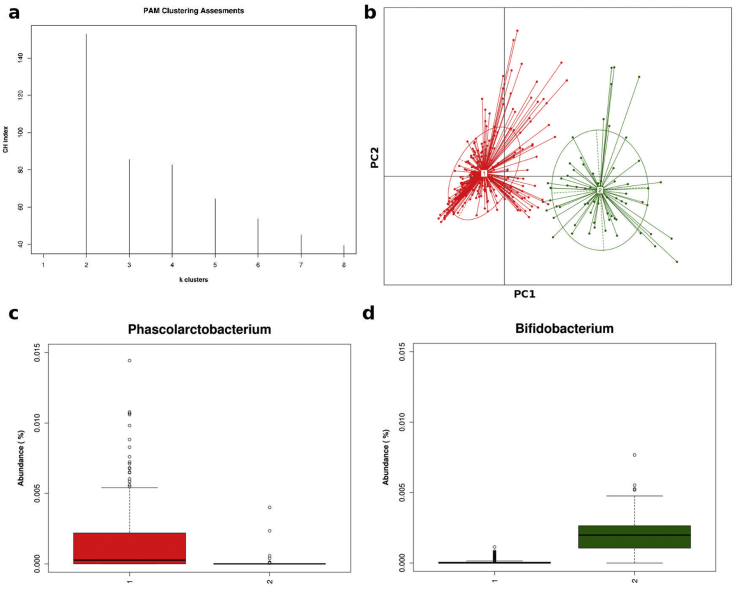

PCoA (Fig. 1a) revealed that the gut microbiota of the tested individuals is based on their genus-level compositions into two distinct clusters (Fig. 1b). The bacterial taxa identified by class analysis as contributing most significantly to each cluster were Phascolarctobacterium for traditional rural individuals and Bifidobacterium for urban individuals (Figs. 1c, d; Table 2). We found differences in the prevalence of several bacterial genera such as Phascolarctobacterium, Ruminococcaceae, Coprococcus and Prevotella, which were overrepresented in traditional rural individuals, whereas Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus and Actinomyces were overrepresented in urban individuals (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 1.

(a) Calinski-Harabasz (CH) index showing optimal number of clusters. (b) Principal coordinate analysis of overall composition of genera communities. (c, d) Two abundant genera in corresponding clusters of urban (green) and traditional rural (red) individuals. Two optimal clusters were revealed by CH index after clustering genus abundances using Jensen-Shannon divergence and partitioning around medoids (PAM) clustering algorithm, which derives from basic k-means algorithm.

Table 2.

Frequencies of bacterial taxa overrepresented within each population group

| Characteristic | Traditional rural | Urban |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional rural | ||

| Phascolarctobacterium | 0.151 | <0.0001 |

| Ruminococcaceae | 0.002 | <0.0001 |

| Coprococcus | 0.002 | <0.0001 |

| Urban | ||

| Bifidobacterium | 0.025 | 0.147 |

| Streptococcus | 0.027 | 0.069 |

| Actinomyces | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Traditional rural communities have richer and more strict anaerobic genera

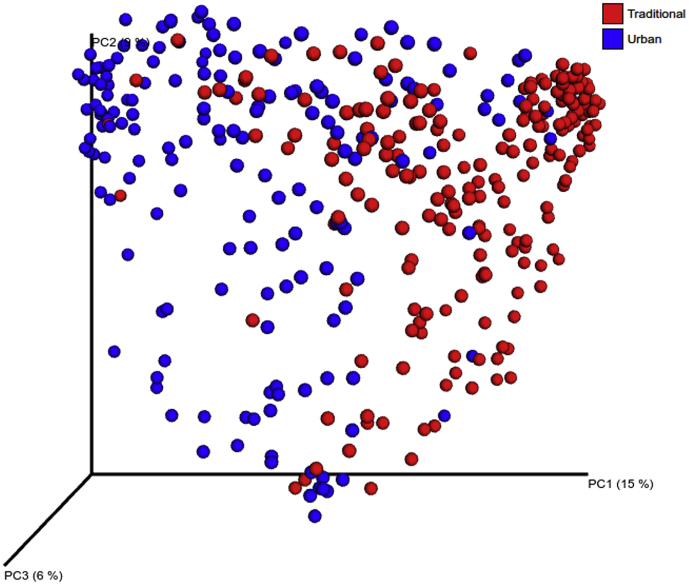

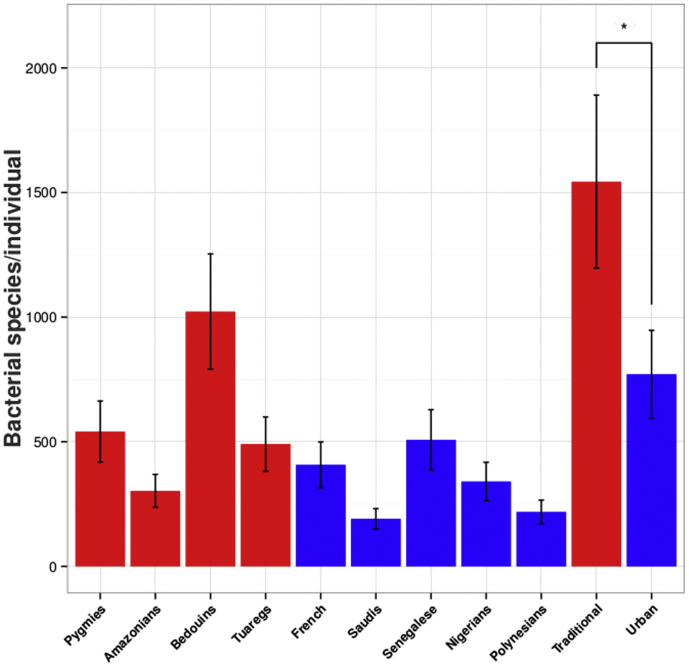

PCoA of the overall composition of the genera communities revealed that the gut microbiota of traditional rural individuals clustered differently to those of urban individuals (Fig. 2). On the basis of species-level Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, we found that the gut microbiota of traditional rural individuals presented significant higher diversity than those living in urban societies (p 0.01) (Fig. 3). This was also confirmed by the rarefaction with the Chao1 measure, which showed that the samples from the traditional rural individuals were richer and more diverse than those of the urban individuals (Supplementary Fig. 7). Moreover, microbial richness revealed that the gut microbiota of Bedouins had greater richness and biodiversity than the other populations tested, while the gut microbiota of Saudis presented lower richness and biodiversity than the other populations.

Fig. 2.

Principal coordinate analysis comparison of microbial community composition between traditional rural and urban individuals.

Fig. 3.

Gut microbiota diminished diversity among populations. Mean numbers of observed bacterial genera per individual at a sequencing depth of 20 000 reads. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals; asterisks denote statistically significant differences at p < 0.001.

We then investigated the distribution of aerobic and strict anaerobic genera residing in the gut microbiota of these groups using the taxonomic classification provided by 16S amplicon analysis. The difference in anaerobic genus counts revealed that French participants had 104 different genera; Saudi participants had 65, Senegalese participants 101, Nigerian participants 94 and Polynesian participants 98 different anaerobic genera in their gut microbiota. In addition, traditional rural Amazonians had 97 different anaerobic genera in their gut microbiota, Pygmies had 112, Bedouins had 93 and Tuaregs had 106. We found that the relative abundance of anaerobic genera was significantly higher in the gut microbiota of Amazonians, Polynesians and Pygmies compared to the other populations (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 8). Finally, we compared the relative abundance of anaerobic genera between traditional rural and urban societies and found that the former presented significant more anaerobic genera in their gut microbiota than the latter (p 0.02).

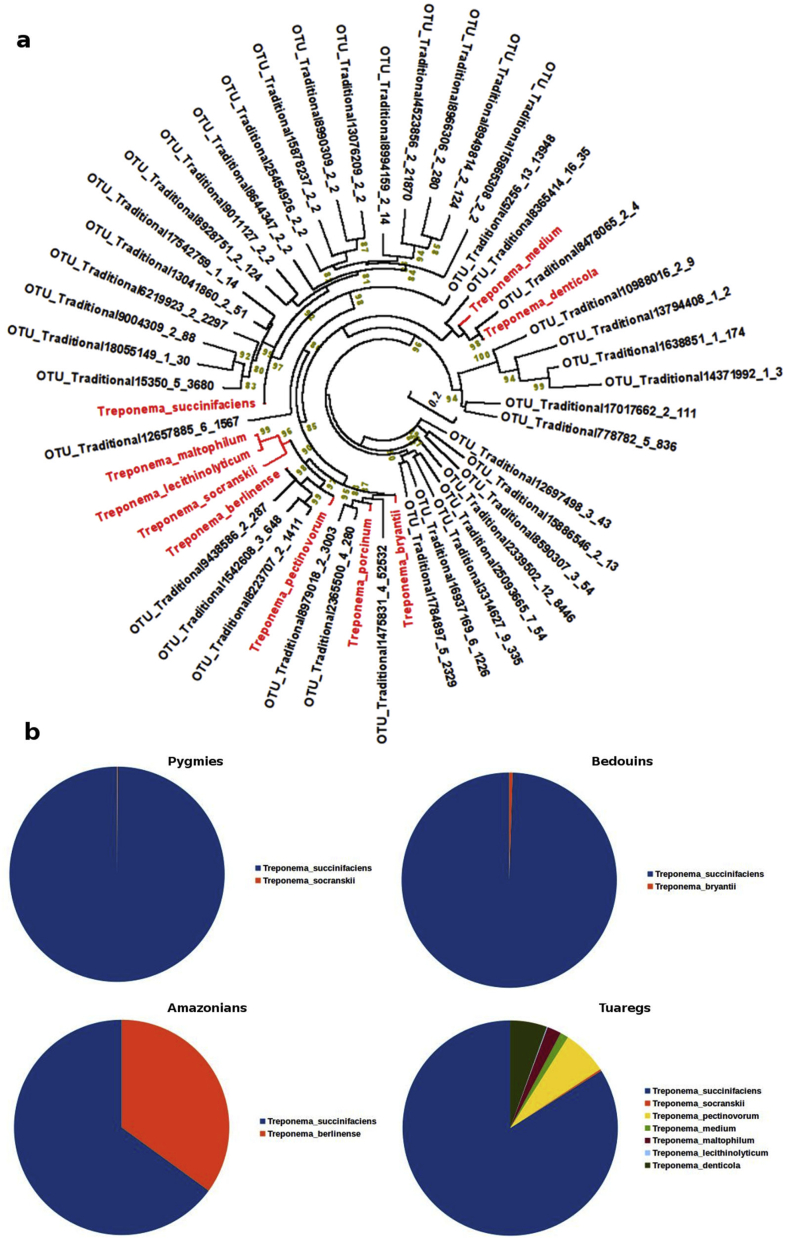

Treponema and traditional rural populations

The presence of Spirochaetes has been reported in the gut microbiota of nonhuman primates [8] and in traditional rural human populations with non-Westernized lifestyles. In line with these studies on traditional rural populations, we found that traditional rural individuals were enriched with Spirochaetes, specifically of the genus Treponema. In contrast, we did not detect any Spirochaetes in the urban populations (Supplementary Fig. 9). Phylogenetic analysis of these Spirochaetes indicated the presence of nine Treponema OTUs found in traditional rural populations. In addition, we performed a neighbour-joining phylogenetic analysis with the nonidentified Treponema OTUs from the 16S rRNA of all samples, and we identified that they belong to at least 48 potentially unidentified Treponema species (Fig. 4a). We then looked for the relative abundance of these Treponema species in the gut microbiota of traditional rural populations. We found that the gut microbiota of all traditional rural populations was enriched with Treponema succinifaciens (Fig. 4b). Moreover, Treponema berlinense was also commonly detected in the gut microbiota of Amazonians, while in the Tuaregs we detected the presence of at least seven different Treponema in gut microbiota.

Fig. 4.

(a) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree constructed using 16S ribosomal RNA sequences from unidentified Treponema operational taxonomic units. (b) Relative abundance of Treponema spp. among different traditional rural populations.

Discussion

We conducted what is to our knowledge the largest-scale study testing the gut microbiota of different human populations living traditional rural and urban lifestyles. The samples that were part of previous studies were processed again, and all samples were analysed the same way. We found that all the traditional rural populations were enriched for Treponema, while in contrast Treponema was not detected at all in the gut microbiota of urban individuals. Spirochaetes have been commonly reported in the gut microbiota of primates such as wild apes [25], macaques [26] and wild hominids [27], and similarly, Treponema have been detected in ancient [28] and traditional rural populations [1], [7]. All the traditional rural populations we tested were enriched for T. succinifaciens; these species are clustered with other Treponema reported from termites [7]. T. succinifaciens was also detected in traditional rural populations from Peru [7]. Moreover, T. berlinense and T. succinifaciens were previously isolated from the gastrointestinal tract of swine [29], [30]. Moreover, because Spirochaetes present increased antimicrobial sensitivity [31], [32], we believe that increased antibiotic use in the nontraditional populations may explain the absence of Spirochaetes from their gut microbiota.

Previous reports have indicated that Western populations have less microbial richness than non-Western populations [3], and our analyses of microbial richness yielded similar results. Indeed, the exposure to a large variety of environmental microbes, associated with a high-fibre diet, could enrich the microbiota [2], [8], [33], [34]. It was also proposed that the microbial diversity of the gut microbiota was possibly decreased during human civilization [35], and recent lifestyle changes in humans have depleted the human microbiota of microbial diversity that was present in ancestors living more wildly [36]. Much of the microbial diversity in the human microbiota may be attributable to the spectrum of microbial enzymatic capacity needed to degrade nutrients, particularly the many forms of complex polysaccharides that are consumed by humans [33], [34].

It has been proposed that Bacteroidetes are the likely primary degraders of the many complex polysaccharides in the plant cell wall, owing to the fact that these bacteria have an expanded repertoire of carbohydrate-active enzymes [34]. Moreover, whole grains are concentrated sources of dietary fibres, resistant starch and oligosaccharides, as well as carbohydrates that escape digestion in the small intestine and are fermented in the gut, producing short-chain fatty acids; for the digestion of plant material through fermentation, an anaerobic environment in the gut is critical [34]. As a result, it is possible that the gut microbiota of traditional rural populations is adapted and enriched with more anaerobic bacteria in order to deal with the increased uptake of starch, fibre and plant polysaccharides. In addition, it is possible that the presence of Prevotella and Treponema in the gut microbiota of traditional rural populations indicates the presence of a bacterial community using xylan, xylose and carboxymethylcellulose to produce high levels of short-chain fatty acids [37]. Indeed, these bacteria can ferment both xylan and cellulose through carbohydrate-active enzymes such as xylanase, carboxymethylcellulase and endoglucanase (http://www.cazy.org/).

The gut microbiota of urban people was enriched by many probiotic bacteria, including Bifidobacterium sp. and Lactobacillus sp. (Supplementary Fig. 6). However, these bacteria were absent from the gut microbiota of traditional rural individuals. Functional food and yoghurts contain very large numbers of living bacteria that can modify the composition of the intestinal microbiota [38]. The market for probiotics is rapidly expanding; the majority of probiotics for human use are Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Saccharomyces [39]. In addition, probiotics have been associated with the reduction of the intestinal microbial diversity in rats [40]. As a result, it is possible that the less microbial richness we found in urban people is also due to the increased consumption of probiotics in this population.

In conclusion, we provide evidence that the gut microbiota of traditional rural societies is different from that of people living in cities. Cross-transmission of Spirochaetes between humans and animals as well as increased antibiotic use by nontraditional populations may explain the fact that Treponema was enriched only in the gut microbiota of the traditional rural populations. Although we conducted a very large study, testing for the first time the gut microbiota of many different traditional rural and urban populations, we believe that our results strongly support the need for human microbiota research on a larger sample of human lifestyles and traditions.

Acknowledgement

Supported in part by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (grant 3-140-1434-HiCi).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2018.10.009.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Schnorr S.L., Candela M., Rampelli S., Centanni M., Consolandi C., Basaglia G. Gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3654. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Filippo C., Cavalieri D., Di Paola M., Ramazzotti M., Poullet J.B., Massart S. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14691–14696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yatsunenko T., Rey F.E., Manary M.J., Trehan I., Dominguez-Bello M.G., Contreras M. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486:222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escobar J.S., Klotz B., Valdes B.E., Agudelo G.M. The gut microbiota of colombians differs from that of Americans, Europeans and Asians. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:311. doi: 10.1186/s12866-014-0311-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehlers S., Kaufmann S.H. Infection, inflammation, and chronic diseases: consequences of a modern lifestyle. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angelakis E., Armougom F., Million M., Raoult D. The relationship between gut microbiota and weight gain in humans. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:91–109. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obregon-Tito A.J., Tito R.Y., Metcalf J., Sankaranarayanan K., Clemente J.C., Ursell L.K. Subsistence strategies in traditional societies distinguish gut microbiomes. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6505. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angelakis E., Yasir M., Bachar D., Azhar E.I., Lagier J.C., Bibi F. Gut microbiome and dietary patterns in different Saudi populations and monkeys. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32191. doi: 10.1038/srep32191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zoetendal E.G., Booijink C.C., Klaassens E.S., Heilig H.G., Kleerebezem M., Smidt H. Isolation of RNA from bacterial samples of the human gastrointestinal tract. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:954–959. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angelakis E., Bachar D., Henrissat B., Armougom F., Audoly G., Lagier J.C. Glycans affect DNA extraction and induce substantial differences in gut metagenomic studies. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26276. doi: 10.1038/srep26276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caporaso J.G., Kuczynski J., Stombaugh J., Bittinger K., Bushman F.D., Costello E.K. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edgar R.C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. 2013;10:996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quast C., Pruesse E., Yilmaz P., Gerken J., Schweer T., Yarza P. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guillou L., Bachar D., Audic S., Bass D., Berney C., Bittner L. The Protist Ribosomal Reference database (PR2): a catalog of unicellular eukaryote small sub-unit rRNA sequences with curated taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D597–D604. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Segata N., Izard J., Waldron L., Gevers D., Miropolsky L., Garrett W.S. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Aust Ecol. 2001;26:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schloss P.D., Westcott S.L., Ryabin T., Hall J.R., Hartmann M., Hollister E.B. Introducing Mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arumugam M., Raes J., Pelletier E., Le P.D., Yamada T., Mende D.R. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calinski T., Harabasz J. A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Commun Stat. 1972;3:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rousseeuw P.J. Silhouettes: a graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J Comput Appl Math. 1987;20:53–65. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubourg G., Lagier J.C., Hue S., Surenaud M., Bachar D., Robert C. Gut microbiota associated with HIV infection is significantly enriched in bacteria tolerant to oxygen. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3 doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2016-000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasir M., Angelakis E., Bibi F., Azhar E.I., Bachar D., Lagier J.C. Comparison of the gut microbiota of people in France and Saudi Arabia. Nutr Diabetes. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/nutd.2015.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Million M., Tidjani A.M., Khelaifia S., Bachar D., Lagier J.C., Dione N. Increased gut redox and depletion of anaerobic and methanogenic prokaryotes in severe acute malnutrition. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26051. doi: 10.1038/srep26051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Bittar F., Keita M.B., Lagier J.C., Peeters M., Delaporte E., Raoult D. Gorilla gorilla gorilla gut: a potential reservoir of pathogenic bacteria as revealed using culturomics and molecular tools. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7174. doi: 10.1038/srep07174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKenna P., Hoffmann C., Minkah N., Aye P.P., Lackner A., Liu Z. The macaque gut microbiome in health, lentiviral infection, and chronic enterocolitis. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochman H., Worobey M., Kuo C.H., Ndjango J.B., Peeters M., Hahn B.H. Evolutionary relationships of wild hominids recapitulated by gut microbial communities. PLoS Biol. 2010;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tito R.Y., Knights D., Metcalf J., Obregon-Tito A.J., Cleeland L., Najar F. Insights from characterizing extinct human gut microbiomes. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cwyk W.M., Canale-Parola E. Treponema succinifaciens sp. nov., an anaerobic spirochete from the swine intestine. Arch Microbiol. 1979;122:231–239. doi: 10.1007/BF00411285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nordhoff M., Taras D., Macha M., Tedin K., Busse H.J., Wieler L.H. Treponema berlinense sp. nov. and Treponema porcinum sp. nov., novel spirochaetes isolated from porcine faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1675–1680. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63388-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Angell J.W., Clegg S.R., Sullivan L.E., Duncan J.S., Grove-White D.H., Carter S.D. In vitro susceptibility of contagious ovine digital dermatitis associated Treponema spp. isolates to antimicrobial agents in the UK. Vet Dermatol. 2015;26:484–485. doi: 10.1111/vde.12269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans N.J., Murray R.D., Carter S.D. Bovine digital dermatitis: current concepts from laboratory to farm. Vet J. 2016;211:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cantarel B.L., Lombard V., Henrissat B. Complex carbohydrate utilization by the healthy human microbiome. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Kaoutari A., Armougom F., Gordon J.I., Raoult D., Henrissat B. The abundance and variety of carbohydrate-active enzymes in the human gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:497–504. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moeller A.H., Degnan P.H., Pusey A.E., Wilson M.L., Hahn B.H., Ochman H. Chimpanzees and humans harbour compositionally similar gut enterotypes. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1179. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blaser M.J., Falkow S. What are the consequences of the disappearing human microbiota? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:887–894. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flint H.J., Bayer E.A., Rincon M.T., Lamed R., White B.A. Polysaccharide utilization by gut bacteria: potential for new insights from genomic analysis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:121–131. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angelakis E., Million M., Henry M., Raoult D. Rapid and accurate bacterial identification in probiotics and yoghurts by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. J Food Sci. 2011;76:M568–M572. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angelakis E., Merhej V., Raoult D. Related actions of probiotics and antibiotics on gut microbiota and weight modification. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:889–899. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uronis J.M., Arthur J.C., Keku T., Fodor A., Carroll I.M., Cruz M.L. Gut microbial diversity is reduced by the probiotic VSL#3 and correlates with decreased TNBS-induced colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:289–297. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.