Abstract

Background

Organ transplantation is considered the ultimate therapy for end-stage organ disease. While pharmacologic immunosuppression is the mainstay of therapeutic strategies to prolong the survival of the graft, long-term use of immunosuppressive medications carries the risk of organ toxicity, malignancies, serious opportunistic infections, and diabetes. Therapies that promote recipient tolerance in solid organ transplantation are able to improve patient outcomes by eliminating the need for long-term immunosuppression.

Summary

Establishing tolerance to an allograft has become an area of intense study and would be the ideal therapy in clinical practice. The discovery of a subset of T cells naturally committed to perform immunoregulation has led to further investigation into their role in the immunopathogenesis of transplantation. Evidence suggests that regulatory T cells (Tregs) are fundamentally involved in promoting allograft tolerance. Efforts to characterize specific markers for Tregs, while challenging, have identified Foxp3 gene expression as a crucial step in promoting the tolerance-inducing features of Tregs. A number of approaches, including those based on targeting the glycogen synthase kinase 3β signaling pathway or activating the melanocortinergic pathway, have been tested as a way to promote Treg lineage commitment and maintenance as well as to facilitate immune tolerance. In order to be effective in clinical practice, Tregs must be allospecific and possess a specific phenotype to avoid suppression of other aspects of the immune system or increasing the risk of malignancy or infections. Multiple experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated the impact of currently used immunosuppressants on the immunoregulatory activities of Tregs and their Foxp3 expression status. Pharmacological induction of tolerogenic Tregs for inducing transplant tolerance, including epigenetic therapies, is in the ascendant.

Key Messages

Therapies that promote Treg function and survival may represent a novel strategy for achieving immune tolerance in transplant patients.

Keywords: Transplant, Allograft, Immune tolerance, Regulatory T cells, Immunosuppressants, Glycogen synthase kinase 3β, Melanocortin

Background

Organ transplantation is the definitive therapy for patients with end-stage organ failure. The major challenge for clinical transplant practice is to deal with the balance between control of the allogeneic immune response and major adverse effects of the immunosuppressive drugs, mainly including life-threatening infection, organ toxicity, diabetes, hypertension, and malignancies [1]. Avoidance of long-term immunosuppression by achieving immunologic tolerance would be the ultimate solution to improve long-term patient and allograft organ survival and provide transplant patients with a better quality of life [2]. The ultimate goal would be to identify an induction protocol to achieve allospecific tolerance as a standard of care for appropriate transplant recipients [3]. Unfortunately, owing to the complex immunopathogenesis, a true immunologic tolerance to avert alloresponse has been difficult to achieve. In particular, once the alloresponse is established, it is extremely difficult to control it because of its strong and self-amplifying effector mechanisms [3].

Transplant tolerance has been defined as maintenance of stable allograft function in the absence of immunosuppressive therapy [2]. An increasing number of “operationally tolerant” patients have been described in literature, demonstrating that this state feasibly exists in humans [4]. The role of regulatory T cells (Treg) in the generation and maintenance of immune tolerance is an attractive yet elusive one [5]. In the early 1970s, a seminal study by Gershon and Kondo [6] unveiled the existence of a population of suppressor T cells. After almost three decades, Sakaguchi et al. [7] demonstrated the existence of a subset of T cells (CD4+CD25+) that appeared to be naturally committed to exert immunoregulation. Several key immunologic findings led to the major effort to induce tolerance by ablation of the mature immune system to allow the establishment of chimerism by transfer of donor bone marrow or lymphoid cells [8]. In adults, ablation of the immune system has been achieved by whole-body irradiation, total lymphoid irradiation, myeloablation by cytotoxic agents, selective T-cell depletion by monoclonal antibodies, or antilymphocyte globulin, which all has led to successful transplant outcomes.

T Cells and Immunology

In the early 1980s, T cells were broadly divided into T-helper cells, which were later better characterized as expressing CD4, and CD8-expressing cytotoxic T cells, which were also thought to include a subpopulation of suppressor T cells [9]. Nearly all studies on suppressor T cells identified suppressor T cells to be CD8 positive. In contrast, T cells positive for CD4 alone could mediate tolerance and actively suppress immune response in an antigen-specific manner [10].

Animals with transplant tolerance can accept graft organs from donors of the same strain in the absence of any immunosuppression or immune manipulation. At the same time, those tolerant hosts reject grafts from a second donor [11], suggesting that transplant tolerance is likely donor specific. In support of this, specific CD4+ T cells from a tolerant host can only suppress the immune response against antigens from its particular donor, but not immune rejection against a second donor [11]. The first evidence that animals with specific immunologic unresponsiveness have an active regulation of suppressor T-cell response was demonstrated by transfer from tolerant hosts of lymph node and spleen cells, which could not restore rejection of donor grafts but still mount an immune response to third-party allografts [11]. A study by Hall [12] to decipher the role of suppressor T cells in maintaining transplant tolerance found that animals given a large number of tolerant peripheral lymphocytes did not reject their grafts; when their grafts had survived more than 75 days, challenge with a large number of naïve T cells did not alter rejection, suggesting that there was an active process suppressing rejection. T cells that can transfer tolerance are short-lived, and if the allograft is removed, the tolerance-transferring capacity will be lost, implying that suppressor T cells are dependent on T-cell-derived cytokines to survive [13].

Development and Subsets of Tregs

Tregs are defined as those anergic and hyporesponsive to stimulation of T-cell receptor (TCR) with suppressive action on the proliferation and activation of helper CD4+ T cells and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells via cell-to-cell contact. Tregs with their Foxp3-expressing marker are strongly suppressive of proliferation of effector T cells and memory T cells, thus controlling excess immune response to foreign antigens, and maintain self-tolerance.

Several studies have examined the characteristic biomarkers of active Tregs in transferring tolerance. Best described is the marker CD25, which is an IL-2 receptor alpha chain that makes those CD4+ T cells responsive to IL-2, a cytokine crucial for inducing T-cell immune response. Another important study found that class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) expression is required to transfer tolerance. The expression of CD25 and that of MHC class II are two of the most common markers of Tregs [14, 15]. Accumulating clinical evidence strongly suggests that a favorable allograft outcome in humans is frequently associated with a robust population of CD4+CD25+ Tregs.

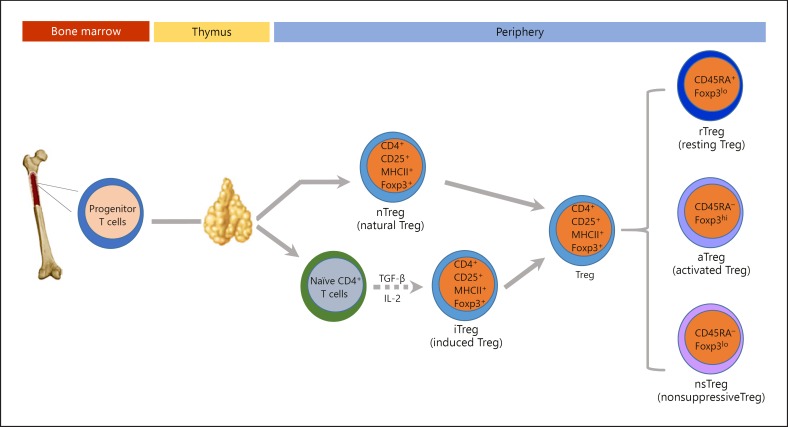

Two major subsets of Tregs have been defined based on their developmental origin: (1) thymus-derived natural Tregs (nTregs), characterized by constitutive Foxp3 expression, and (2) peripheral induced Tregs (iTregs), where Foxp3 expression seems unstable [14]. Although both T-cell subsets possess regulatory properties, they differ in their developmental pathways, TCR repertoires, and activation requirements. nTregs develop within the thymic medulla, around Hassall's corpuscles, under the effect of both IL-2 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (Fig. 1). The other crucial step for Treg development is the engagement of TCRs with MHCII molecules loaded with self-peptides. After exiting the thymus, nTregs form 5–10% of the total peripheral T cells. Their presence in the periphery as a stable population of T cells contributes to the maintenance of peripheral tolerance and prevents the development of autoimmunity [16]. In contrast, iTregs develop in the periphery under the influence of different cytokines as an adaptive immune response. A milieu rich in IL-2 and TGF-β appears to polarize the naïve T cells towards iTregs [14, 16]. This makes iTregs display more flexible biomarker features with the capacity to transform into different T-cell subtypes depending on the prevailing cytokine milieu [17]. Clinical trials have shown that iTregs generated in vitro are comparable to nTregs in immunoregulatory activity. However, withdrawal of the TGF-β from iTreg cultures will result in rapid loss of Foxp3 expression, along with a reversion to a cell phenotype akin to conventional CD4+ T cells [18]. In stark contrast, Foxp3 expression by nTregs is independent of TGF-β, as evidenced by the normal amount and function of nTregs in TGF-β-deficient mice [19].

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram depicting regulatory T cell development, polarization, and subpopulations. Foxp3, forkhead box P3; IL-2, interleukin-2; MHCII, major histocompatibility complex class II; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; Treg, regulatory T cell.

To add complexity to Treg heterogeneity, there is evidence suggesting that even Foxp3+ Tregs are not functionally homogeneous. Kuczma et al. [20] showed that human CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs are actually composed of three distinct subpopulations: CD45RA+Foxp3lo, CD45RA–Foxp3hi, and CD45RA–Foxp3lo cells (Fig. 1). CD45RA+Foxp3lo and CD45RA–Foxp3hi cells both possess the functionality of suppressive Tregs as proved in vitro. However, CD45RA–Foxp3lo Tregs are mostly considered as a nonsuppressive subtype and secrete distinct cytokines, which ultimately have no suppressive activity [20].

Markers of Authenticity of Tregs

The phenotypic plasticity displayed by iTregs, when compared to nTregs, may be due to a relatively unstable expression of Foxp3 in the former population, which in turn could be partially attributable to epigenetic differences in the Foxp3 gene between these two Treg subsets [21]. The Foxp3 gene is demethylated in the so-called Treg-specific demethylation region (TSDR) in nTregs, but is methylated in iTregs [22]. Demethylation in the TSDR on the Foxp3 gene has bene proposed to be a hallmark characteristic of authentic Tregs, differentiating them from recently activated CD4+ T cells [23], which can also express Foxp3 transiently upon activation [22, 23]. However, unlike in nTregs, the TSDR gene is methylated in recently activated T cells. Therefore, researchers have proposed that an analysis of the methylation status in the Foxp3 gene TSDR can differentiate genuine Tregs from recently activated conventional T cells. This epigenetic modification of Tregs includes histone modification, chromatin interaction, and DNA methylation, and thus plays an important role in Treg differentiation [24]. Thus, demethylation in the Foxp3 gene region is important not only for the expression of Foxp3 but also to ensure the suppressive function of those particular Tregs [24, 25]. Researchers have concluded that a more precise, reliable delineation of the real phenotype of Tregs based on methylation status is likely to better reflect the true clinical significance and potential diagnostic and clinical implications of Tregs.

Although expression of Foxp3, a transcriptional repressor, appears to be the most reliable signature of both nTregs and iTregs [25], Foxp3 is not expressed on the cell membranes, which precludes its use as a selection marker for isolation. Nevertheless, detection of Foxp3 expression or transcription has been employed by many investigators as a surrogate marker for the presence or involvement of Tregs in immunoregulation [26].

Researchers have confirmed the importance of TGF-β1 in vitro for the expansion of Foxp3-expressing Tregs. They also have shown in vitro that TGF-β1 can protect T cells from apoptosis and convert naïve CD4+CD25– T cells into Foxp3-expressing Tregs [27]. More than 40% of the differentially expressed genes in blood cells from tolerant patients are dependent on the TGF-β1 signaling pathway. TGF-β1 in conjunction with TCR stimulation can progressively induce complete demethylation of the Foxp3 gene in Tregs in vivo.

Epigenetic Immunotherapy

Epigenetic therapy has been defined as regulation of gene expression via modification of either chromosomal DNA or proteins interacting with DNA without inducing changes in the DNA sequence of the genome. This type of therapy mostly consists of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibition or histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition. Lal and Bromberg [21] demonstrated the ability of both DNMT inhibitors and HDAC inhibitors to generate stable Foxp3+ Tregs and to mediate immunosuppression. DNMT inhibitors mostly consist of nucleoside analogs and a few nonnucleoside DNMT inhibitors. It has been shown that decitabine or 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, a nucleoside analog used in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome, was able to regulate Foxp3 demethylation in naïve CD4+CD25– T cells and to generate functional, stable, and specific Tregs [28]. To date, the only approved DNMT inhibitors for therapy belong to the nucleoside-based family of drugs, which, however, may lead to toxic side effects and display poor specificity as well as high chemical instability. Only a few nonnucleoside DNMT inhibitors have been identified so far, and even fewer have been validated in diseases like cancer. As to HDAC inhibition, pan-HDAC inhibitors, including trichostatin A, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, and other similar hydroxamate compounds, are able to induce stable Foxp3 expression and boost Treg function even at nanomolar concentrations in both experimental models and human T cells [29].

Cell Signaling Pathways That Control Treg Lineage Commitment and Maintenance

In addition to epigenetic regulation, a number of cell signaling pathways have been implicated in controlling Treg polarization and dictating immune tolerance versus immunity. These include the Wnt pathway, JAK/STAT signaling, CD28 signaling, and toll-like receptor signaling [30]. As a multitasking cell signaling kinase situated at the nexus of diverse pathways involved in the control of Treg lineage commitment and maintenance, glycogen synthase kinase (GSK) 3β has recently attracted attention [31] as a protein kinase that mediates immune intolerance [31]. As a matter of fact, both NFκB, the transcription factor responsible for inflammation and immune response, and CREB, a key transcription factor transmitting anti-inflammation and immune tolerance, are substrates for GSK3β [32]. GSK3β catalyzes the phosphorylation of NFκB and CREB and regulates the counterbalance of NFκB-mediated immunity and CREB-mediated immune tolerance [31]. Inhibition of GSK3β was able to prolong Foxp3 expression in Tregs [33]. Systemic administration of GSK3β inhibitor resulted in prolonged islet survival in an allotransplant mouse model, suggesting that GSK3β could be a promising therapeutic target to increase the stability and function of Tregs for inducing allotransplant tolerance [33]. Inhibition of GSK3β could be achieved by a number of cytokines, growth factors, and humoral factors in humans [34], including some neuropeptides like melanocortins and adrenocorticotropic hormone [35, 36, 37, 38]. In support of this, treatment of primed T cells with the melanocortin peptide α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) could induce tolerance/anergy in primed CD4+ T-helper cells and mediate induction of CD25+CD4+ Tregs through an MC5R-dependent mechanism, thus resulting in tolerance to experimental autoimmune injuries [39, 40, 41]. Moreover, α-MSH treatment is able to augment Foxp3 messaging in effector T cells and converts them into Tregs, which suppress immunity by targeting specific antigens and tissues [39]. Collectively, novel regimens based on targeting the GSK3β signaling pathway or activating the melanocortinergic pathway may represent promising therapeutic strategies for boosting Tregs and attaining immune tolerance.

Effects of Immunosuppressive Drugs on Foxp3+ Tregs

Immunosuppressive drugs that are used to prevent or treat rejection in kidney transplant patients have different effects on Tregs. Most immunosuppressive agents target intracellular signals that are involved in T-cell activation following antigen stimulation. Recent clinical studies have shown that different immunosuppressive agents have different effects on the quantity and functionality of Tregs (Table 1). As outlined earlier, specific phenotypes of Tregs, such as CD4, CD25, and Foxp3, are critical to programing the suppressor activity of T cells. Understanding the molecular intracellular signaling mechanisms of diverse immunosuppressants is crucial to decipher the effects of different drugs on the quantity as well as the quality of Tregs. In aggregate, at least three major signaling pathways are implicated in Treg regulation: (1) the calcineurin-NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T cells) pathway; (2) the IL-2 receptor-STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) pathway; and (3) the TGF-β-Smad (small mothers against decapentaplegic) pathway. To date, a number of animal and clinical studies have been conducted to assess the functional and phenotypic status of Tregs under the influence of various immunosuppressive drugs in an effort to prevent rejection and induce tolerance if possible.

Table 1.

Effects of currently used immunosuppressants on Tregs

| Immunosuppressants | Effects on Tregs | Reference No. |

|---|---|---|

| Induction therapy | ||

| Anti-thymocyte globulins (ATG) | Potentiate Treg expansion, as evidenced in experimental models | 53 |

| Basiliximab, daclizumab (anti-IL-2R antibodies) | Controversial in vivo and in vitro data | 54–56 |

| Alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 antibody) | Potentiates Treg expansion, as shown in experimental models | 57 |

| Maintenance therapy | ||

| Corticosteroids | Preserve the suppressive activity and prolong the survival of Tregs both in vivo and in vitro | 50, 51 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | Controversial effects on Tregs | 47–49 |

| Calcineurin inhibitors | Inhibit Foxp3 expression and suppress Treg function in vitro and in vivo, as evidenced by some clinical data | 47 |

| mTOR inhibitors | Promote Treg survival and function and augment its suppressive activity, as evidenced by in vivo, in vitro, and clinical data | 47 |

| Tregs, regulatory T cells. | ||

Effects of Maintenance Immunosuppressive Therapies on Foxp3+ Tregs

Much research effort has been dedicated to comparing mechanistically the effects of mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) inhibitors with those of calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) on suppressive Tregs. Foxp3+ Tregs can be expanded with rapamycin without losing their suppressive activity [42]. San Segundo et al. [43] performed a clinical cohort study to evaluate renal transplant recipients with stable function under maintenance treatment with CNIs or rapamycin. Twelve months after transplantation, the number of Foxp3+ Tregs was significantly lower in the patients treated with CNIs than in the rapamycin-treated patients, as measured by flow cytometry. However, the expression level of Foxp3 on individual Tregs was not affected [43]. In another study, Baan et al. [44] examined heart transplant recipients and found that rapamycin inhibited IL-2 production, but preserved TGF-β1, which is essential to the induction of the regulatory phenotype of CD4+CD25– T cells. Unlike CNIs, rapamycin promotes Treg survival and function by suppressing effector T cells. In addition, in vivo studies have demonstrated that treatment with rapamycin exerts favorable effects on Treg induction, as evidenced by ex vivo expansion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs and prevention of rejection in islet transplantation, possibly again mediated by a TGF-β1-dependent mechanism [45]. In a clinical cohort study, Chu and Ji [46] investigated the prevalence of Tregs in renal transplant recipients receiving different types of immunosuppressive drugs. Their results were in line with previous findings and revealed that CNIs significantly decreased the percentage of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs, while the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus did not [46]. They concluded that sirolimus facilitates the induction of Tregs, whereas CNI hampers their development. Surprisingly, graft function after 5 years did not correlate with the level of CD4+CD25+ T cells, suggesting the involvement of multiple factors in determining the function of the graft [46].

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and mycophenolate sodium are prodrugs of mycophenolic acid, an inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase that blocks de novo synthesis of guanosine nucleotides essential for T-cell proliferation. Zeiser et al. [47] provided the first line of evidence that MMF and rapamycin, rather than CNI, preserve functional Treg expansion and Foxp3 expression in mice. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that rapamycin and MMF profoundly affect the phenotype and function of the antigen-presenting cells by reducing the uptake of the antigens and by mitigating the expression of costimulatory molecules, favoring the differentiation of tolerant T cells [48]. In contrast, some studies demonstrated that MMF reduces CD25 expression in a dose-dependent manner. Aside from these conflicting findings on the effect of MMF on Tregs, the concomitant use of other immunosuppressants may make it difficult to assess the individual effect of MMF on Tregs in humans [49].

Corticosteroids are known to exert an inhibitory effect on transcriptional factors (NFκB, Stat3, etc.) that are involved in the production of IL-2 and other cytokines, like TNF-α and INF-γ. In addition, CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells express the glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor, which regulates Treg function to promote peripheral tolerance [50]. In some experimental studies, dexamethasone triggered short- and long-term Foxp3 and IL-10 expression in T-cell cultures while preserving the suppressive ability of Tregs [51]. It has been shown that corticosteroids can improve the suppressive activity of Tregs both in vitro and in vivo, likely dependent on IL-2 inhibition.

Effects of Induction Immunosuppressive Therapies on Foxp3+ Tregs

In the field of allotransplantation, anti-thymocyte globulins (ATGs) are the most commonly used induction therapy in diverse transplant centers [52]. ATGs induce T-lymphocyte depletion through different mechanisms, including complement-dependent cell lysis and T-cell apoptosis predominantly in the circulating compartment. Interestingly, several studies have shown that ATGs also play a role in modulating human Treg expansion and functionality and Foxp3 expression both in vivo and in vitro [53]. ATG treatment caused rapid and sustained Treg expansion in cultured human lymphocytes with high expression of Foxp3. Both in vivo and in vitro data have demonstrated that ATG has a profound effect on the number of CD4+CD25+ T cells but does not affect their function.

IL-2 receptor antagonists are a second, widely used induction immunosuppressive therapy, comprising the chimeric antibody basiliximab and the humanized antibody daclizumab. These monoclonal antibodies directly interfere with IL-2 receptor signaling by blocking IL-2 binding to its receptor and the subsequent phosphorylation of the receptor's alpha and beta chains [33]. The effect of IL-2R antagonists on Tregs is controversial. Some studies have shown an inhibitory effect on the induction of Foxp3 mRNA by daclizumab in allostimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells [44]. Along the same lines, Wang et al. [54] demonstrated a downregulation in the number of CD25+ T cells after short-term basiliximab treatment, though the immunosuppressive activity of Tregs was likely unaffected. The decreased number of CD25+ T cells, however, may be a technical artifact, because basiliximab has been shown to interfere with anti-CD25 monoclonal antibodies used for flow cytometry detection. In agreement, others have demonstrated that donor-reactive Tregs are minimally affected in transplant patients after basiliximab or daclizumab induction [55], and CD25 does not appear to be essential for maintaining human peripheral Tregs in vivo [56]. Alemtuzumab is another biologic drug used for induction immunosuppression. It is a humanized antibody targeting CD52 that is expressed by T and B lymphocytes. Recent experimental evidence suggests that alemtuzumab is likely able to increase the proportion of Tregs in vitro [57].

Conclusion and Perspectives

Therapies that promote Treg function and survival are likely able to improve kidney transplantation outcomes by eliminating the need for immunosuppressants and their adverse effects. In addition to their promise in inducing graft tolerance and minimizing the use of immunosuppressants in transplant patients, Tregs have been used experimentally to explore treatment of other autoimmune disease conditions, such as colitis, lupus, diabetes mellitus, and glomerulonephritis. The first proof-of-concept clinical trial of polyclonal adaptive Treg transfer to treat graft-versus-host disease turned out to be promising [58]. A major limitation of polyclonal Tregs is the low abundance of the specific clones of interest within the polyclonal repertoire. While antigen-specific Tregs would be superior, their isolation and expansion are still challenging. Recently, Trivedi et al. [59] conducted a clinical trial on a group of live-donor renal transplantation patients using pretransplant stem cell transplantation. The patients achieved successful withdrawal of the immunosuppressants with low-dose daily steroid monotherapy. They concluded that generation of peripheral Tregs was necessary to maintain tolerance and that the survival and presence of Tregs is important to protect the graft from chronic rejection.

Future research on Treg cellular therapy should be focused on optimizing Treg expansion with specific phenotypic features that convey the suppressive functionality and on minimizing contamination by other nonsuppressive Tregs. Pharmacological approaches targeting epigenetic mechanisms as well as other cell signaling pathways, like the GSK3β or melanocortinergic pathways, may represent novel therapeutic strategies for achieving better tolerance by increasing the specific suppressive activity of Tregs in the periphery and in the graft. This would be particularly attractive for the repurposed use of FDA-approved drugs that are able to target these pathways, like lithium carbonate and the melanocortin neuropeptide adrenocorticotropic hormone, which both have demonstrated powerful immunotolerogenic activity that is attributable to their potent modulatory effect on Tregs.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed.

Acknowledgements

The research work of the authors was supported in part by US National Institutes of Health grants DK092485 and DK114006 (to Rujun Gong) and by Natural Science Foundation of China grant 81770672. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of this study, the collection and interpretation of the data, or the preparation and approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Halloran PF. Immunosuppressive drugs for kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2715–2729. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra033540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scandling JD, Busque S, Shizuru JA, Engleman EG, Strober S. Induced immune tolerance for kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1359–1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1107841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starzl TE. Immunosuppressive therapy and tolerance of organ allografts. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:407–411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0707578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roussey-Kesler G, Giral M, Moreau A, Subra JF, Legendre C, Noël C, et al. Clinical operational tolerance after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:736–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braza F, Durand M, Degauque N, Brouard S. Regulatory T cells in kidney transplantation: new directions? Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2288–2300. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gershon RK, Kondo K. Infectious immunological tolerance. Immunology. 1971;21:903–914. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25) Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155:1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scandling JD, Busque S, Dejbakhsh-Jones S, Benike C, Millan MT, Shizuru JA, et al. Tolerance and chimerism after renal and hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:362–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Adra AR, Pilarski LM, McKenzie IF. Surface markers on the T cells that regulate cytotoxic T-cell responses I. The Ly phenotype of suppressor T cells changes as a function of time, and is distinct from that of helper or cytotoxic T cells. Immunogenetics. 1980;10:521–533. doi: 10.1007/BF01572587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alpdogan O, van den Brink MR. Immune tolerance and transplantation. Semin Oncol. 2012;39:629–642. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall BM. Mechanisms maintaining enhancement of allografts. I. Demonstration of a specific suppressor cell. J Exp Med. 1985;161:123–133. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Boehmer H. Dynamics of suppressor T cells: in vivo veritas. J Exp Med. 2003;198:845–849. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waight JD, Takai S, Marelli B, Qin G, Hance KW, Zhang D, et al. Cutting edge: epigenetic regulation of Foxp3 defines a stable population of CD4+ regulatory T cells in tumors from mice and humans. J Immunol. 2015;194:878–882. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green DR, Flood PM, Gershon RK. Immunoregulatory T-cell pathways. Annu Rev Immunol. 1983;1:439–463. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.01.040183.002255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molinero LL, Yang J, Gajewski T, Abraham C, Farrar MA, Alegre ML. CARMA1 controls an early checkpoint in the thymic development of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:6736–6743. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, Lei KJ, Li L, Marinos N, et al. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25 naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-β induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selvaraj RK, Geiger TL. A kinetic and dynamic analysis of Foxp3 induced in T cells by TGF-β. J Immunol. 2007;179 11 p following 1390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fahlén L, Read S, Gorelik L, Hurst SD, Coffman RL, Flavell RA, et al. T cells that cannot respond to TGF-β escape control by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:737–746. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuczma M, Pawlikowska I, Kopij M, Podolsky R, Rempala GA, Kraj P. TCR repertoire and Foxp3 expression define functionally distinct subsets of CD4+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:3118–3129. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lal G, Bromberg JS. Epigenetic mechanisms of regulation of Foxp3 expression. Blood. 2009;114:3727–3735. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron U, Floess S, Wieczorek G, Baumann K, Grützkau A, Dong J, et al. DNA demethylation in the human FOXP3 locus discriminates regulatory T cells from activated FOXP3+ conventional T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2378–2389. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bestard O, Cuñetti L, Cruzado JM, Lucia M, Valdez R, Olek S, et al. Intragraft regulatory T cells in protocol biopsies retain Foxp3 demethylation and are protective biomarkers for kidney graft outcome. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2162–2172. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lafaille JJ. Natural and adaptive Foxp3+ regulatory T cells: more of the same or a division of labor? Immunity. 2009;30:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko SA, Ramsdell F. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:337–342. doi: 10.1038/ni909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo X, Jie Y, Ren D, Zeng H, Zhang Y, He Y, et al. In vitro-expanded CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ regulatory T cells controls corneal allograft rejection. Hum Immunol. 2012;73:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brouard S, Mansfield E, Braud C, Li L, Giral M, Hsieh SC, et al. Identification of a peripheral blood transcriptional biomarker panel associated with operational renal allograft tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15448–15453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705834104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kehrmann J, Tatura R, Zeschnigk M, Probst-Kepper M, Geffers R, Steinmann J, et al. Impact of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine and epigallocatechin-3-gallate for induction of human regulatory T cells. Immunology. 2014;142:384–395. doi: 10.1111/imm.12261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lal G, Zhang N, van der Touw W, Ding Y, Ju W, Bottinger EP, et al. Epigenetic regulation of Foxp3 expression in regulatory T cells by DNA methylation. J Immunol. 2009;182:259–273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li MO, Rudensky AY. T cell receptor signalling in the control of regulatory T cell differentiation and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:220–233. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woodgett JR, Ohashi PS. GSK3: an in-Toll-erant protein kinase? Nat Immunol. 2005;6:751–752. doi: 10.1038/ni0805-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin M, Rehani K, Jope RS, Michalek SM. Toll-like receptor-mediated cytokine production is differentially regulated by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:777–784. doi: 10.1038/ni1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graham JA, Fray M, de Haseth S, Lee KM, Lian MM, Chase CM, et al. Suppressive regulatory T cell activity is potentiated by glycogen synthase kinase 3β inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32852–32859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.150904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beurel E, Grieco SF, Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;148:114–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gong R. Leveraging melanocortin pathways to treat glomerular diseases. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21:134–151. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiao Y, Berg AL, Wang P, Ge Y, Quan S, Zhou S, et al. MC1R is dispensable for the proteinuria reducing and glomerular protective effect of melanocortin therapy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27589. doi: 10.1038/srep27589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang P, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Brem AS, Liu Z, Gong R. Acquired resistance to corticotropin therapy in nephrotic syndrome: role of de novo neutralizing antibody. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20162169. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonzalez-Rey E, Chorny A, Delgado M. Regulation of immune tolerance by anti-inflammatory neuropeptides. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:52–63. doi: 10.1038/nri1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor AW, Lee DJ. The alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone induces conversion of effector T cells into Treg cells. J Transplant. 2011;2011:246856. doi: 10.1155/2011/246856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luger TA, Kalden D, Scholzen TE, Brzoska T. α-Melanocyte-stimulating hormone as a mediator of tolerance induction. Pathobiology. 1999;67:318–321. doi: 10.1159/000028089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor AW. The immunomodulating neuropeptide α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) suppresses LPS-stimulated TLR4 with IRAK-M in macrophages. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;162:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Battaglia M, Stabilini A, Roncarolo MG. Rapamycin selectively expands CD4+CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Blood. 2005;105:4743–4748. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.San Segundo D, Ruiz JC, Fernández-Fresnedo G, Izquierdo M, Gómez-Alamillo C, Cacho E, et al. Calcineurin inhibitors affect circulating regulatory T cells in stable renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:2391–2393. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.08.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baan CC, van der Mast BJ, Klepper M, Mol WM, Peeters AM, Korevaar SS, et al. Differential effect of calcineurin inhibitors, anti-CD25 antibodies and rapamycin on the induction of FOXP3 in human T cells. Transplantation. 2005;80:110–117. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000164142.98167.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pothoven KL, Kheradmand T, Yang Q, Houlihan JL, Zhang H, Degutes M, et al. Rapamycin-conditioned donor dendritic cells differentiate CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells in vitro with TGF-β1 for islet transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1774–1784. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chu ZQ, Ji Q. Sirolimus did not affect CD4+CD25high forkhead box p3+ T cells of peripheral blood in renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:153–156. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.07.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zeiser R, Nguyen VH, Beilhack A, Buess M, Schulz S, Baker J, et al. Inhibition of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell function by calcineurin-dependent interleukin-2 production. Blood. 2006;108:390–399. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hackstein H, Taner T, Logar AJ, Thomson AW. Rapamycin inhibits macropinocytosis and mannose receptor-mediated endocytosis by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2002;100:1084–1087. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dummer CD, Carpio VN, Gonçalves LF, Manfro RC, Veronese FV. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells: from suppression of rejection to induction of renal allograft tolerance. Transpl Immunol. 2012;26:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karagiannidis C, Akdis M, Holopainen P, Woolley NJ, Hense G, Rückert B, et al. Glucocorticoids upregulate FOXP3 expression and regulatory T cells in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1425–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen X, Oppenheim JJ, Winkler-Pickett RT, Ortaldo JR, Howard OM. Glucocorticoid amplifies IL-2-dependent expansion of functional FoxP3+CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells in vivo and enhances their capacity to suppress EAE. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2139–2149. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hardinger KL, Brennan DC, Klein CL. Selection of induction therapy in kidney transplantation. Transpl Int. 2013;26:662–672. doi: 10.1111/tri.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lopez M, Clarkson MR, Albin M, Sayegh MH, Najafian N. A novel mechanism of action for anti-thymocyte globulin: induction of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2844–2853. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Z, Shi BY, Qian YY, Cai M, Wang Q. Short-term anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody administration down-regulated CD25 expression without eliminating the neogenetic functional regulatory T cells in kidney transplantation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;155:496–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Furukawa A, Wisel SA, Tang Q. Impact of immune-modulatory drugs on regulatory T cell. Transplantation. 2016;100:2288–2300. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Goër de Herve MG, Gonzales E, Hendel-Chavez H, Décline JL, Mourier O, Abbed K, et al. CD25 appears non essential for human peripheral Treg maintenance in vivo. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Havari E, Turner MJ, Campos-Rivera J, Shankara S, Nguyen TH, Roberts B, et al. Impact of alemtuzumab treatment on the survival and function of human regulatory T cells in vitro. Immunology. 2014;141:123–131. doi: 10.1111/imm.12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Di Ianni M, Falzetti F, Carotti A, Terenzi A, Castellino F, Bonifacio E, et al. Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:3921–3928. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trivedi HL, Vanikar AV, Kute VB, Patel HV, Gumber MR, Shah PR, et al. The effect of stem cell transplantation on immunosuppression in living donor renal transplantation: a clinical trial. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2013;4:155–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]