Abstract

This review examined effects of structured exercise (aerobic walking, with or without complementary modes of exercise) on cardiorespiratory measures, mobility, functional status, healthcare utilization, and Quality of Life in older adults (≥60 years) hospitalized for acute medical illness. Inclusion required exercise protocol, at least one patient-level or utilization outcome, and at least one physical assessment point during hospitalization or within 1 month of intervention. MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL databases were searched for studies published from 2000 to March 2015. Qualitative synthesis of 12 articles, reporting on 11 randomized controlled (RCT) and quasi-experimental studies described a heterogeneous set of exercise programs and reported mixed results across outcome categories. Methodological quality was independently assessed by 2 reviewers using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias tool. Larger, well-designed RCTs are needed, incorporating measurement of pre-morbid function, randomization with intention-to-treat analysis, examination of a targeted intervention with pre-defined intensity, and reported adherence and attrition.

Keywords: Exercise, Hospitalization, Outcome Assessment, Quality of Life, Older Adults

Introduction

All stakeholders - health care providers, delivery systems, policy communities, patients and families - share concern for older adults who require hospitalization and seek interventions that support restorative processes. Hospitalized older adults are at high risk for rapid deconditioning and functional decline (Anpalahan & Gibson, 2008; Cynthia M. Boyd et al., 2008; Kenneth E. Covinsky, Pierluissi, & Johnston, 2011; Creditor, 1993; Kortebein, 2009; Mahoney, Sager, & Jalaluddin, 1998; Sager et al., 1996). Within 24 to 48 hours of bed rest inactivity, multiple changes in organ system physiology begin to occur and contribute to overall weakness and functional decline (Creditor, 1993; Kleinpell RM, 2008). Even in healthy older adults prolonged bed rest results in substantial loss of lean body mass in the lower extremities, primarily as a result of skeletal muscle wasting (Kortebein et al., 2008; Puthucheary et al., 2013). Without a preventive intervention, hospital-associated deconditioning and disability has the potential to precipitate short and long-term consequences including loss of mobility, independence and quality of life. Additional negative outcomes may include falls, the need for higher levels of care, and readmission, all resulting in higher healthcare costs (Kalisch, Dabney, & Lee, 2013). Older adults who are already functionally compromised prior to admission may be at particularly high risk of these outcomes.

Based on its well-recognized, positive effects in healthy, community-dwelling adults, structured exercise is one intervention of interest. It has been shown to thwart the process of deconditioning, build resilience (Luthar SS, 2000), abbreviate the periods of exacerbation of acute illness, and reduce the impact of subsequent health crises (Hawkley LC, 2005). In contrast, for older adults hospitalized with acute illness the specific effects of structured exercise remain ill-defined.

Our systematic review refines and extends previous work by de Morton, Keating, & Jeffs, specifically the 2007 Cochrane review of 9 trials, 7 of which were published between 1986 and 2000. Of the 9 trials, 6 represented multicomponent intervention versus 3 exercise-only intervention trials. Reviews of multicomponent programs for hospitalized older adults, which included exercise as one of its components, have been associated with improved patient outcomes (Bachmann et al., 2010; Baztan, Suarez-Garcia, Lopez-Arrieta, Rodriguez-Manas, & Rodriguez-Artalejo, 2009; Counsell et al., 2000; Fleck et al., 2012; Inouye, Bogardus, Baker, Leo-Summers, & Cooney, 2000; Landefeld, Palmer, Kresevic, Fortinsky, & Kowal, 1995). In multicomponent models, however, it is not possible to disentangle effects of structured exercise from other intervention components, such as a specially designed environment or input from a multidisciplinary team (Landefeld et al., 1995). Multicomponent programs have not been widely adopted, and this may be due in part to uncertainty about the relative impact of individual program features.

Our literature review, starting in 2000 and extending through March 2015 overlaps and advances the 2007 Cochrane review by focusing exclusively on structured exercise interventions, thus allowing a more precise estimate of its isolated effects among hospitalized older adults in the inpatient setting and extending to home/community-based interventions.

This review examined effects of structured exercise (defined as aerobic walking, with or without complementary modes of exercise) on performance measures, mobility, functional status, healthcare utilization and Quality of Life, in older adults hospitalized for acute medical illness. Specific objectives of this review were to answer the following key questions: 1) How effective are structured exercise interventions for older adults hospitalized with medical illness in improving the above mentioned outcomes?, and 2) How do variables such as exercise parameters, target population, and health care setting modify the effectiveness of exercise interventions?

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

Using pre-defined PICOT guidelines (summarization of population, intervention, comparison, outcome and time) as shown in Table 1 and in consultation with a medical librarian, we searched MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL with a combination of subject headings and text words for inpatients, elderly, and exercise. We narrowed results to randomized controlled (RCT) and quasi-experimental trials using a modified version of the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions). Results were further limited to those published in the English language from 2000 to March 2015 to achieve overlap with timeframe of the 2007 Cochrane Review as described above. The full search strategy is available in Appendix 1. Duplicate citations were eliminated using EndNote software, resulting in 2506 citations. The Prospero registration number for this study is CRD42015019161.

Table 1:

PICOT guidelines

| Study characteristic | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Older adults hospitalized with acute medical

episode; studies for which older adults’ participation is

recorded for:

|

Studies without significant population of older adults (as defined above); studies that exclusively enrolled patients expected to have a new mobility impairment (i.e., stroke, hip fracture); post-surgical patients; patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). |

| Intervention |

“Structured exercise

intervention” includes inpatient execution of:

|

Multicomponent intervention, i.e., programs that include elements not focused on exercise or mobility, e.g., medical or geriatric consultation |

| Comparator | Usual care; attention control | None; study must have an external control condition |

| Outcome | At least one patient level or utilization outcome | Only reports safety outcomes |

| Timing | At least one assessment point during hospitalization or within 1 month of intervention | No assessment |

| Setting | Inpatient acute care unit |

|

| Study design |

|

Cross-sectional studies and other observational study designs not specifically listed as “included” study designs |

| Publications |

|

|

Study Selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were pre-specified to focus on older adults who were hospitalized for an acute medical episode (PICOT Table 1). Studies in which all patients were ≥60 years, median age of ≥60, and with at least 50% of participants ≥60 years were included. The intervention setting included at least an inpatient hospital stay with the possibility of extending the intervention to a home/community-based setting. The comparator was usual care or attention control. In brief, included articles had to report: exercise protocol and parameters, at least one patient-level or utilization outcome, and at least one physical assessment point during hospitalization or within 1 month of intervention.

Specifically excluded were studies of multicomponent interventions, that is programs that included medical or geriatric consultation, studies that only reported safety outcomes, and specific settings of intensive care, psychiatric units, skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation centers and exclusively outpatient settings.

Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

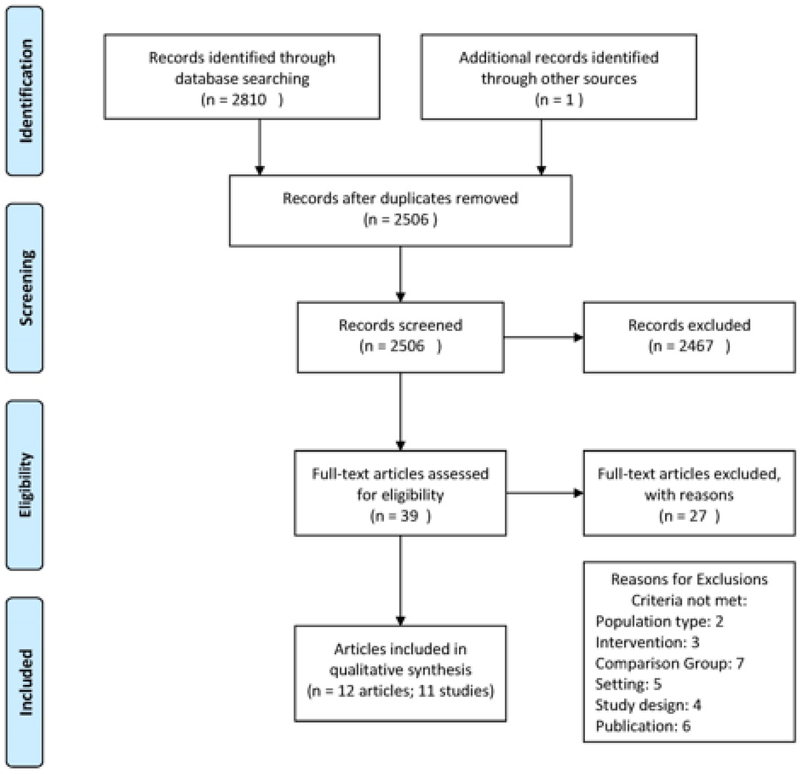

A publicly available abstracting tool, Abstrackr, was used for citation management (Wallace BC, 2012). Two investigators independently assessed titles and abstracts. Full-text articles identified by either investigator as relevant were retrieved for further review; disagreements on inclusion/exclusion were resolved by discussion or by a third investigator. The PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1 outlines the process steps and outcomes of the literature search Total records identified in the search were 2506; 39 articles received full-text review. Twelve articles, reporting on 11 trials described effects of exercise intervention on patient-level or utilization outcomes.

Figure 1:

PRISMA flow diagram.

Risk of bias (ROB) (Appendix 2) and outcome data were then abstracted independently by two investigators. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or a third investigator. Risk of bias assessment was performed, at the study level, using key quality criteria described in the Cochrane Collaboration ROB Tool (CCRBT) (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions). This ROB tool evaluates 6 different domains with guidelines to score each item; each domain was evaluated as low, unclear/medium, or high ROB.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We identified five outcome categories of interest. Cardiorespiratory capacity and/or performance represent measurable capacity (e.g., maximum oxygen consumption and airflow obstruction) and performance (e.g., walk distances, walk time). Mobility refers to assessments of basic motor skills required for functional ambulation (e.g., Timed Up and Go [TUG] Functional Ambulatory Classification Score). Functional status includes self-reported measures of Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL). Healthcare utilization comprises all measures of planned and unplanned use of health care services and discharge destination. QoL/patient experience incorporates responses to validated, survey instruments, perception of health status, and self-reported patient experience.

The studies were stratified by setting (Inpatient Hospital versus Inpatient Hospital to Home/Community Settings) and within setting by exercise intervention mode to: 1) identify and compare patterns of outcome measures, both primary and secondary, and 2) to evaluate the relationship of characteristics of individual studies and their findings.

Results

Summary study characteristics

Total records identified in the search were 2506; 39 articles received full-text review. Twelve articles, representing 11 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis. (Figure 1) Table 2 provides an overview of characteristics and outcomes of exercise interventions for included studies distinguished by exercise mode. Overall the review included data from 11 published studies, including 7 RCTs, (Behnke M, 2003; Courtney et al., 2012; Eaton T, 2009; Greening NJ, 2014; Jones CT, 2006; Ozdirenc M, 2004; Siebens, Aronow, Edwards, & Ghasemi, 2000) 3 cluster randomized trials, (de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, Jackson, & Lim, 2007; Mudge AM, 2008; Mundy, Leet, Darst, Schnitzler, & Dunagan, 2003) and 1 non-randomized, concurrent control study (Hastings, Sloane, Morey, Pavon, & Hoenig, 2014). Assessment of ROB found 2 studies as low risk (i.e. high quality) (Jones CT, 2006; Siebens et al., 2000), 5 studies as unclear/medium risk (de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Eaton T, 2009; Greening NJ, 2014; Hastings et al., 2014; Mudge AM, 2008), and 4 studies as high risk (Behnke M, 2003; Courtney et al., 2012; Mundy et al., 2003; Ozdirenc M, 2004). Studies were conducted at hospitals in Australia (5), USA (3), UK (1), Germany (1), and Turkey (1). Six studies included patients with general medical conditions (Courtney et al., 2012; de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Hastings et al., 2014; Jones CT, 2006; Mudge AM, 2008; Siebens et al., 2000), 4 with respiratory illness (Behnke M, 2003; Eaton T, 2009; Greening NJ, 2014; Mundy et al., 2003), and 1 with type II diabetes (Ozdirenc M, 2004). Exercise intervention mode included aerobic walking alone in 4 studies (Behnke M, 2003; Hastings et al., 2014; Mudge AM, 2008; Mundy et al., 2003), aerobic and resistance exercise in 3 studies (de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Eaton T, 2009; Greening NJ, 2014), and aerobic, resistance, balance and/or flexibility exercise in 4 studies (Courtney M, 2009; Courtney et al., 2012; Jones CT, 2006; Ozdirenc M, 2004; Siebens et al., 2000). Six studies performed the intervention in the inpatient setting only (de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Hastings et al., 2014; Jones CT, 2006; Mudge AM, 2008; Mundy et al., 2003; Ozdirenc M, 2004), 4 studies extended it to home-based setting (Behnke M, 2003; Courtney M, 2009; Courtney et al., 2012; Greening NJ, 2014; Siebens et al., 2000), and 1 study extended to both home-based and outpatient settings (Eaton T, 2009). Outcome assessment was executed at variable time points, ranging from the end of hospital stay to 18 months post-hospitalization.

Table 2:

Study characteristics and outcomes of exercise interventions for hospitalized older adults by setting

| First author, year Design Dx Focus Setting |

Participants: Total

N Intervention/Control N Age % Male % Attrition % Adherence ROB Power calculation Intention to treat principle |

Primary outcome | Outcome Measures by Categories | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardio-respiratory capacity and/or performance | Mobility | Functional status | Utilization | QoL/patient experience | ||||||

| INPATIENT HOSPITAL SETTING | ||||||||||

| Aerobic Exercise | ||||||||||

|

Hastings,

2014 Non-randomized concurrent control [29] Dx: Medical |

Participants: 127 I=92/C=35 Age: 74±7/75±8 % Male: 96.7/3.3 % Attrition: 7 % Adherence: 76 ROB: Unclear risk Power calculation: Not reported Intention to treat principle: No |

None specified | Discharge to home I=92%; C=74% p=0.007 Median Length of Stay;30-day ED visits and readmission rate |

|||||||

|

Mudge,

2008

Cluster randomized trial [30] Dx:Medical |

Participants:

124 I=62/C=62 Age:81.7±7.8/82.4±7.4 % Male:43.5/40.3 % Attrition: No attrition % Adherence: Not reported ROB: Unclear risk Power calculation: Not reported Intention to treat principle: Yes |

Modified Barthel

Index p=0.03 |

Timed Up and Go | modified Barthel Index I=8.5 points (IQR 3–19); C=3.5 points (IQR 0–15) p=0.03 |

Change in mobility Length of Stay Discharge destination 30-day readmission |

|||||

| Mundy, 2003 Cluster randomized trial [33] Dx: Community Acquired Pneumonia |

Participants:

458 I=227/C=231 Age: 17–103 % Male: 44/56 % Attrition: No attrition % Adherence: 73 ROB: High risk Power calculation: Yes Intention to treat principle: Yes |

Length of

stay Significant reduction; No p value reported |

Length of stay I=5.8 (0.43) 95% CI 0.0 – 2.2; C=6.9 (0.36) 95% CI 0.2 – 5.0 Significant reduction; No p value reported Emergency Department visits (30 and 90 days) |

Mundy,

2003 Cluster randomized trial [33] Dx: Community Acquired Pneumonia Setting: Inpatient |

||||||

|

Aerobic and Resistance

Exercise | ||||||||||

|

deMorton,

2007 Cluster randomized trial [26] Dx: Medical |

Participants:

236 I=110/C=126 Age: 80±8 % Male: 44.5/46 % Attrition: 29 % Adherence: Not reported ROB: Unclear risk Power calculation: Yes Intention to treat principle: Yes |

Discharge destination – no significant effect on any outcome | Functional Ambulatory

Classification Score Timed Up and Go |

Barthel Index | Discharge destination Length of Stay Intensive Care Unit admission 28-day readmission |

|||||

| Aerobic, Resistance, Balance and/or Flexibility Exercise | ||||||||||

| Jones, 2006 RCT [24] Dx: Medical |

Participants:

160 I=80/C=80 Age:81.9±8/82.9±7.6 % Male:42.6/38.7 % Attrition: 24 % Adherence: 94 ROB: Low risk Power calculation: Yes Intention to treat principle: Yes |

Modified Barthel Index – in multivariate analysis when admission mBI scores were low, there was a greater improvement in mBI scores in intervention group compared with control group | Timed Up and Go (decrease in seconds) I=5.4 (1.0, 12.4); C= 1.2 (−0.9, 4.3) p=0.012 |

Modified Barthel Index – in multivariate analysis when admission mBI scores were low, there was a greater improvement in mBI scores in intervention group compared with control group | Discharge destination Length of stay in acute care; Length of stay in sub-acute care; Total Length of stay (acute plus sub-acute): HR 1.46 (95%CI 1.04 – 2.05); p = 0.026 Admission to Intensive Care Unit |

Jones, 2006 RCT [24] Dx: Medical Setting: Inpatient |

||||

| Ozdirenc,

2003 RCT [34] Dx:Type II Diabetes Mellitus |

Participants:

44 I=23/C=21 Age:60.9±19.9 % Male:78.3/88.9 % Attrition: Not reported % Adherence: Not reported ROB: High risk Power calculation: Not reported Intention to treat principle: Not reported |

6MWD p<0.05 |

6MWD I=537.6 m; C= 511.5 m p<0.05 Estimated VO2 max I=18.2;C= 14.9 p<0.05 |

|||||||

| INPATIENT HOSPITAL TO HOME/COMMUNITY SETTINGS | ||||||||||

| Aerobic Exercise | ||||||||||

|

Behnke,

2003 RCT [31] Dx: COPD |

Participants: 26 I=14/C=12 Age: 64±7.5/69.0±6.9 % Male: 78.6/75 % Attrition: 13 % Adherence: Not reported ROB: High risk Power calculation: Not reported Intention to treat principle: NR |

# hospital admissions I=3; C=14 p=0.026 |

6MWD I=518 (438; 597); C=208 (148; 270) p<0.001 |

# hospital

admissions p=0.026 |

Chronic Respiratory Disease

Questionnaire I=117 (108;126); C=77 (62; 92) p<0.001 Transitional Dyspnea Index I=4.4 (4.4; 2.9); C= −3.1 (−5.4; −0.7) p<0.05 |

|||||

| Aerobic and Resistance Exercise | ||||||||||

| Eaton,

2008 RCT [27] Dx:COPD |

Participants: 97 I=47/C=50 Age: 78 (65–96) % Male: 38/62 % Attrition: 13 % Adherence: 40 ROB: Unclear risk Power calculation: Yes Intention to treat principle: Yes |

# COPD-related readmission days – no significant difference | BODE Index Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea score Exercise capacity index SaO2 airflow obstruction 6MWD |

# COPD-related readmission days Time to 1st COPD-related readmission Length of stay |

Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire–Self

Administered (fatigue) T0–T1 (3 months) significant differences between intervention and control groups on all subscales except dyspnea SF-36 Physical Component Score Intervention T0–T1 (3 months) Intervention attendees (vs. non-attendees) significantly better than control (p=0.04) Hospital anxiety and depression scale (anxiety) T0–T1 (3 months) Significantly less for intervention attendees vs. control (p=0.02) |

|||||

|

Greening,

2014 RCT [28] Dx: Chronic respiratory disease |

Participants:

389 I=196/C=193 Age: 45–93 yrs. % Male: 45/44 % Attrition: 32 % Adherence: 86 ROB: Unclear risk Power calculation: Yes Primary outcome only Intention to treat principle: Yes |

Unplanned readmission at 12 months – no significant difference between groups | Endurance shuttle

walk Author notes adherence associated with increases in exercise training walk times (76s, 95% CI 56 −96s) p<0.001 |

Unplanned readmissions (12

months) Length of stay Time for first readmission # unplanned admissions by cause (respiratory/non-respiratory) |

St. George’s respiratory score | |||||

| Aerobic, Resistance, Balance and/or Flexibility Exercise | ||||||||||

| Courtney, 2009, 2012 RCT [32,35] Dx: Medical |

Participants:

128 I=64/C=64 Age:78.1±6.3/79.4±7.3 % Male: 37.9/62.1 % Attrition: I=22/C=9 % Adherence: 72 ROB: Unclear risk Power calculation: Part of a larger study in which power calculation was reported Intention to treat principle: Yes |

WIQ distance WIQ speed WIQ stairs T0–T4 biggest improvement in first 4 weeks p<0.001 ADL I (4 weeks) p<0.001 I (24 weeks) p<0.001 IADL I (4 weeks) p<0.001 I (24 weeks) p<0.001 Emergency hospital admissions T0–T1 (4 weeks) p<.05 T0–T3 (24 weeks) p=.007 Emergency GP visits T0–T1 (4 weeks) p<.005 T0–T3 (24 weeks) p=.001 Emergency Allied health visits T0–T1 (4 weeks) p<.05 T0–T3 (24 weeks) p=.04 SF-12 Physical Component Score I (24 weeks) p<0.001 SF-12 Mental Component Score I (24 weeks) p<0.001 |

Modified Walking Impairment

Questionnaire (WIQ) WIQ distance Intervention (4weeks)=53.62(25.88); C=28.90 (30.21) p<0.001 WIQ speed I (4 weeks) =41.30 (21.90); C=22.09 (22.52); p<0.001 WIQ stairs I (4 weeks)= 46.73 (29.35); C=26.06 (25.65); p<0.001 |

ADLs I (4 weeks) 0.07 (0.25); C=0.69 (1.21) p<0.001 I (24 weeks) 0.16 (0.42) C=1.27 (1.71) F(3, 282)=9.733, p<0.001 IADLs I (4 weeks)1.47 (1.50); C=3.29 (2.03) p<0.001 I (24 weeks) 1.13 (1.71); C=4.33 (2.15) F(3, 282)- 30.645, p<0.001 |

Emergency hospital

admissions T0–T1 (4 weeks) p<.05 T0–T3 (24 weeks) I= 22%; C=46.7% p=.007 Emergency General Practitioner visits T0–T1 (4 weeks) p<.005 T0–T3 (24 weeks) I= 25.0%; 67.3% p=.001 Emergency Allied health visits T0–T1 (4 weeks) p<.05 T0–T3 (24 weeks) I=2; C=13 p=.04 |

SF-12 Physical Component Score I (24 weeks) = 43.8±9.4; C=26.0±9.9 p<0.001 SF-12 Mental Component Score I (24 weeks) =59.4±5.1; C=48.3±7.7 p<0.001 |

||||

|

Siebens,

2000 RCT [25] Dx: Medical & Surgical |

Participants:

300 I=149/C=151 Age: 78.5/78.2 %Male: 40.9/37.8 % Attrition: 10 % Adherence: 42 ROB: Low risk Power calculation: Yes Intention to treat principle: Yes |

Length of stay – no significant difference | IADLs I= mean 5.1 (SD 2.0); C= 4.6 (2.2) (Beta=.443; 95% CI .044,.842 p<.05 Functional Independence Measure Locomotion scale Frequency of leaving neighborhood National Health Interview Survey physical activity scale |

Length of stay | RAND general health scale |

|||||

| # of positive outcomes per category (#, % of total) |

12/19; 63% | 3/9; 33% | 4/7; 57% | 5/11; 45% | 7/35; 20% | 7/9; 78% | ||||

Notes: DX – diagnosis; Gen Med-General Medical; CAP-community acquired pneumonia; DM-diabetes mellitus; I-intervnetion; C-control; A-aerobic; R-resistance; B/F-balance and/or flexibility; NR-not reported; min.-minutes; mBI-modified Barthel index; TUG-timed up and go; LOS-length of stay; 6MWD-6 minute walking distance; PT-physical therapy; SF-12 PCS - short form physical component score; SF12 MCS-short form mental component score; Surg-surgical; COPD- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ADL-activities of daily living; IADL-instrumental activities of daily living; WIQ-walking impairment questionnaire; GP-general practitioner; TDI-transitional dyspnea index; CRD-chronic respiratory disease questionnaire; w/i-within;ROB-risk of bias;ED-emergency department; T0- time point 0;T1-time point 1; ‘+’-positive increase in intervention group; ‘−’- effective reduction in measure for intervention group; NS-not specified

In total, the review considers studies of 2089 participants. Study sizes included 3 studies with <100 participants (Behnke M, 2003; Eaton T, 2009; Ozdirenc M, 2004), 4 studies between 101 and 200 participants (Courtney et al., 2012; Hastings et al., 2014; Jones CT, 2006; Mudge AM, 2008), and 4 studies between 201 and 500 participants(de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Greening NJ, 2014; Mundy et al., 2003; Siebens et al., 2000). The age range of study participants was 17 to 103 years; 2 studies enrolled participants below the age of 60 years (Greening NJ, 2014; Mundy et al., 2003). Average age, among 9 studies reporting mean age, was 75 years (range 60 to 96 years). Males represented between 38% and 97% of study populations.

Key Question 1: Effect of exercise on cardiorespiratory capacity and/or performance, mobility, functional status, healthcare utilization, and quality of life (QoL)/patient experience

Study results are summarized in Table 2. In general, findings were mixed both within and across the 5 outcome categories.

Cardiorespiratory capacity and/or performance.

Five studies reported cardiorespiratory measures, though none was considered a primary outcome (Behnke M, 2003; Eaton T, 2009; Greening NJ, 2014; Mundy et al., 2003; Ozdirenc M, 2004). More consistent impact was observed for performance than for capacity measures. Three studies showed significant findings toward beneficial effects in performance (Behnke M, 2003; Greening NJ, 2014; Ozdirenc M, 2004); 6 minute walk distance (6MWD) was improved in the Behnke (Behnke M, 2003) and Ozdirenc (Ozdirenc M, 2004) studies which used aerobic and aerobic, resistance and flexibility exercises respectively as the intervention; and the endurance shuttle walk time improved in the Greening study (Greening NJ, 2014), which used aerobic and resistance exercise as the intervention. The Ozdirenc (Ozdirenc M, 2004) study demonstrated a significant difference in capacity, as measured by estimated maximal oxygen consumption (Vo2 max), between intervention and control groups.

Mobility.

Four studies (Courtney et al., 2012; de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Jones CT, 2006; Mudge AM, 2008) specified a mobility outcome including Timed Up and Go, Functional Ambulatory Classification Score, and Modified Walking Impairment Questioinnaire. Positive mobility effects were evident in two studies that combined walking plus resistance, balance and/or flexibility exercises. The Courtney study, including exercise in inpatient and home settings, found significant between-group differences (P<.001) in the primary outcome measure of modified walking impairment (mWIQ) for distance, speed and stairs with the largest improvement in the first 4 weeks post-hospitalization (Courtney et al., 2012). Jones, an inpatient-setting only trial, showed a significant difference (P=0.01) in Timed Up and Go (Jones CT, 2006).

Functional Status.

Three studies specified one or more functional status measures as a primary outcome (Courtney et al., 2012; Jones CT, 2006; Mudge AM, 2008). Of 3 studies examining inpatient exercise alone (de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Jones CT, 2006; Mudge AM, 2008), Mudge (Mudge AM, 2008) reported significant improvement in ADLs using the Barthel Index, while deMorton (de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007) did not. Jones (Jones CT, 2006) reported a greater improvement in Modified Barthel Index (mBI) scores in the intervention group when admission mBI scores were low.

Among studies that examined multiple settings, Siebens (Siebens et al., 2000) and Courtney (Courtney et al., 2012) reported significant improvement in IADLs. Courtney collected outcome data at 4, 12, and 24 weeks following discharge and reported the greatest improvement in both ADLs and IADLs was observed in the first 4 weeks post hospitalization.

Utilization.

A total of 35 utilization measures (9 specified as primary) were reported among 10 of 11 studies; yet only 20% of measures were significant. Primary outcome measures that significantly favored the intervention group in any study included: length of stay (LOS) (Mundy et al., 2003); number of hospital admissions (Behnke M, 2003); and percent of emergency hospital admissions, emergency general practitioner visits and emergency allied health services (Courtney M, 2009). Seven studies measured LOS (de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Eaton T, 2009; Greening NJ, 2014; Hastings et al., 2014; Mudge AM, 2008; Mundy et al., 2003; Siebens et al., 2000). Only one study in this review, Mundy et al, reported a statistically significant reduction in hospital length of stay (Mundy et al., 2003); notably this study (n=458) was explicitly powered to detect a one-day difference in LOS for patients with community acquired pneumonia (Mundy et al., 2003). It is unclear how many of the other included studies were adequately powered to assess this outcome. Seven studies included readmission measures (Behnke M, 2003; Courtney M, 2009; de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Eaton T, 2009; Greening NJ, 2014; Hastings et al., 2014; Mudge AM, 2008); 2 studies showed significant findings (Behnke M, 2003; Courtney et al., 2012). The Courtney study, (Courtney et al., 2012) which implemented both inpatient and home-based exercise, evidenced multiple positive utilization findings with significantly fewer emergency readmissions at both 4 and 24 weeks in the intervention group (Courtney M, 2009). Significant findings of secondary outcomes of utilization included between group differences in discharge disposition in Hastings (Hastings et al., 2014) walking study.

Quality of life/patient experience.

Five of 11 studies measured QoL/patient experience (Behnke M, 2003; Courtney M, 2009; Eaton T, 2009; Greening NJ, 2014; Siebens et al., 2000). The QoL/patient experience findings tended to be the most consistently positive category of outcomes across studies; 7 of a total of 9 (78%) measures (i.e., chronic respiratory disease questionnaire, transitional dyspnea index, SF-12 physical component score, hospital anxiety and depression index, St. George’s respiratory score, SF-12 mental component score, and Rand general health scale)demonstrated significant findings. The Courtney study which was the only one to specify QoL/patient experience as a primary outcome measure, found highly significant differences at 24 weeks in both Short Form (SF)-12 Physical Health Component Score (PCS) and Mental Health Component Score (MCS) with greater improvement for the intervention group (Courtney M, 2009).

Key Question 2: Factors modifying effectiveness of interventions

Intervention characteristics.

Exercise interventions varied considerably across studies and are summarized in Table 3. Four studies encompassing 395 patients included aerobic walking as the sole exercise mode (Behnke M, 2003; Hastings et al., 2014; Mudge AM, 2008; Mundy et al., 2003); all except Behnke were inpatient-only programs. Three studies accounting for 393 participants applied aerobic and resistance exercise interventions; 1 was inpatient only (de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007), 1 combined inpatient and home-based, (Greening NJ, 2014), and 1 used inpatient, outpatient and home-based settings (Eaton T, 2009). Four studies with 316 total participants used aerobic, resistance and balance and/or flexibility exercises; of these, 2 studies were conducted in inpatient settings (Jones CT, 2006; Ozdirenc M, 2004) and 2 studies extended to home (Courtney et al., 2012; Siebens et al., 2000). Six studies specified the timeframe to initiate the exercise intervention, ranging from 24 to 72 hours of admission. Inpatient exercise was prescribed at least once each day in all but one study (Courtney et al., 2012), and 4 studies specified twice daily inpatient exercise (de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Jones CT, 2006; Mudge AM, 2008; Siebens et al., 2000). In contrast to a daily routine, the Courtney study (Courtney M, 2009) provided exercise 2–3 times per week while inpatient and markedly increased frequency for home based exercise to 3 to 4 days per week and 1 to 3 times per day (Courtney et al., 2012). Where specified, session duration ranged from 5 to 45 minutes and averaged 20–30 minutes per day. Intervention duration varied from the length of hospital stay (5 to 12 days) to 18 months, with varying specifications for intensity and progression. Individualized training was noted in 5 studies (Behnke M, 2003; Courtney et al., 2012; de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Greening NJ, 2014; Jones CT, 2006); of these, 3 tailored exercise according to the patient’s functional status (de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Jones CT, 2006; Mudge AM, 2008).

Table 3:

Exercise interventions, prescriptions, and settings

| First author, | Mode of Training | Setting | Program duration | Session duration | Frequency | Intensity | Progression | Supervision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INPATIENT HOSPITAL SETTING | ||||||||

| Aerobic Exercise | ||||||||

| Hastings [29] |

Walking | Inpatient | Hospital length of stay | As tolerated up to 20 min | Daily | Not Specified | Increase as tolerated up to 20 min | Physical Therapist, Walking Aide |

| Mudge [30] |

Exercise determined by functional status: bed, sitting, standing, or walking-based exercise | Inpatient | Within 48 hours and through hospital length of stay | Not Specified | 2x/day | Not Specified | Increase exercise level per functional status | Physiotherapist |

| Mundy [33] |

Mobility (movement out of bed with change from horizontal to upright position, including walking) | Inpatient | Within first 24hr of admission and through hospital length of stay | ≥ 20 min | Daily | Not Specified | Progressive mobilization each subsequent day of hospitalization | Not Specified |

| Aerobic and Resistance Exercise | ||||||||

| deMorton [26] |

Exercise Levels determined by functional

status: Level 1 – bed exercise; Level 2 – sitting

exercise; Level 3 – standing exercise; Levels 4 – stair

exercise. All levels performed Upper Extremity, Lower Extremity, and trunk strengthening (gravity, body weight, and/or light weights) |

Inpatient | Within 48 hours of admission and through hospital length of stay | 20–30 min | Inpatient: 2x/day, 5 days/week | Not Specified | Walking: Once at level to do so, increase

distance as tolerated Strengthening: Increase resistance upon completion of 10 reps |

Physiotherapist, Allied Health Assistant |

| Aerobic, Resistance, Balance and/or Flexibility Exercise | ||||||||

| Jones [24] |

Exercise level determined by functional status: Level 1 – bed and sitting exercise; Level 2 – sitting to standing exercise; Level 3 – standing to walking exercise; Level 4 – walking to stair climbing exercise. All levels performed strengthening (gravity, body weight), and balance | Inpatient | Hospital length of stay | 30 min | 2x/day | Not Specified | Increase exercise level per functional status | Allied Health Assistant |

| Ozdirenc [34] |

Walking; strengthening (resistance bands); flexibility | Inpatient | Hospital Length of stay | 10–45 min | 5x/week | Not Specified-submaximal | Walking: Increase to 30

min Strengthening: increase reps and/or resistance as tolerated |

Physiotherapist |

| INPATIENT HOSPITAL TO HOME/COMMUNITY SETTINGS | ||||||||

| Aerobic Exercise | ||||||||

| Behnke [31] |

Walking (corridor, treadmill) | Combined (Inpatient, Home-based) | Inpatient: 10 days Home-based: 18 months |

Inpatient: Not Specified Home-based: 15 min |

Inpatient: 1x/day Home-based: 3x/day |

Walking: achieving in each 15 min session 125% of the best hospital self-paced, horizontal 6MWD | Not Specified | IN: Not Specified HB: Medical

Doctor |

| Aerobic and Resistance Exercise | ||||||||

| Eaton [27] |

Walking; strengthening | Combined: Inpatient, Outpatient, Home-based | Inpatient: Within 48 hours of admission and

through hospital length of stay Outpatient: 8 weeks Home-based: 8 weeks |

Inpatient: 30 min Outpatient: 60 min Home-based: 30 min |

Inpatient: Daily Outpatient: 2x/week Home-based: Daily |

Not Specified | Increase as tolerated ≥ 30 min | Inpatient: Nursing Outpatient: Not Specified Home-based: Not Specified |

| Greening [28] |

Walking; strengthening (gravity, body weight,

weights); Neuro-muscular electrical stimulation to quadriceps |

Combined: Inpatient, Home-based | Inpatient: Hospital LOS Home-based: 6 weeks |

Inpatient: Not specified for walking or

strengthening; 30 min Neuro-muscular electrical stimulation

Home-based: Not specified |

Inpatient: Daily Home-based: Walking (daily); strengthening (3x/week); Neuro-muscular electrical stimulation (daily) |

Walking: 85% predicted VO2 max,

3–5 Borg breathless-ness score (DOE), ≤ 13 Borg Rating

Perceived Exertion Strengthening: 3 sets 8 reps or 70% 1RM |

Walking: Increase time at set walking

speed Strengthening: Increase load by 0.5 kg once 3 sets 8 reps performed at RPE < 13 |

Inpatient: Pulmonary rehabilitation team (Physical Therapy, Nursing) |

| Aerobic, Resistance, Balance and/or Flexibility Exercise | ||||||||

| Courtney [32,35] |

Walking; UE and LE strengthening (resistance band); balance; flexibility | Combined (Inpatient, Home-based) | Inpatient: Within 72 hours of admission and

through hospital length of stay Home-based: 24 weeks |

Inpatient: Not Specified Home-based: Not Specified |

Walking, strengthening,

flexibility: Inpatient: 2–3x/week Home-based: 3–4x/week Balance: daily |

Walking: slow pace for 3–5 min,

moderate pace for 5–10 min, slow pace for 3–5

min Strengthening: lowest level resistance band, contraction held 3–5 sec, 1 set x 5 reps |

Walking: 2–3x/week to

3–4x/week Strengthening: 2–3x/week to 3–4x/week, build to 2–3 sets of 10 reps, progress level of resistance band |

Inpatient: Physiotherapist,

Nursing Home-based: Nursing |

| Siebens [25] |

Walking; strengthening; flexibility | Combined: Inpatient, Home-based | Inpatient: Within 48 to 72 hours of admission

through hospital Length of stay Home-based: 4 weeks |

Inpatient: 5–30 min Home-based: 5–30 min |

Inpatient: 2x/day (1x/day with aide, 1x/day

independently) Home-based: 3x/week (24 sessions) |

Walking: 60–80% predicted Heart Rate

max, talk test Strengthening: 5 reps of 8 exercises |

Walking: Increase from 5 min to 30

min Strengthening: Increase to 10 reps |

Inpatient: Physical Therapy, Physical Therapy

aide Home-based: None |

Notes: DX – diagnosis; Gen Med-General Medical; CAP-community acquired pneumonia; DM-diabetes mellitus; I-intervnetion; C-control; A-aerobic; R-resistance; B/F-balance and/or flexibility; NR-not reported; min.-minutes; mBI-modified Barthel index; TUG-timed up and go; LOS-length of stay; 6MWD-6 minute walking distance; PT-physical therapy; SF-12 PCS - short form physical component score; SF12 MCS-short form mental component score; Surg-surgical; COPD- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ADL-activities of daily living; IADL-instrumental activities of daily living; WIQ-walking impairment questionnaire; GP-general practitioner; TDI-transitional dyspnea index; CRD-chronic respiratory disease questionnaire; w/i-within;ROB-risk of bias;ED-emergency department; T0- time point 0;T1-time point 1; ‘+’-positive increase in intervention group; ‘−’- effective reduction in measure for intervention group; NS-not specified

Setting.

Studies examining interventions that extended beyond hospitalization evidenced a greater absolute number of significant findings. Five studies extended the intervention to home and/or outpatient settings. Of four studies that included home-based exercise (Behnke M, 2003; Courtney et al., 2012; Greening NJ, 2014; Siebens et al., 2000), all but 1 reported between 2 and 5 significant between-group differences (Siebens et al., 2000). All five studies that included home-based exercise included some level of patient support follow-up including home visit (Courtney et al., 2012), telephone calls (Siebens et al., 2000; Courtney et al., 2012; Greening NJ, 2014; Behnke M, 2003), and an encouragement postcard (Siebens et al, 2000). The Eaton study offered free outpatient oxygen to participants, free door-to-door transport to an outpatient exercise program, and a free prescription to a local gym to maintain an exercise regimen. One trial, Eaton et al (Eaton T, 2009), used all three settings and reported 3 significant findings in QoL category only (CRQ-Self Administered fatigue score, SF-36 PCS, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety score) (Eaton T, 2009). In contrast, the 6 inpatient-only studies evidenced a more limited number of significant findings. One study did not report any significant finding (de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007) and 5 reported one significant finding each (Hastings et al., 2014; Jones CT, 2006; Mudge AM, 2008; Mundy et al., 2003; Ozdirenc M, 2004) across outcome categories (discharge to home, mBI, LOS, TUG, and 6MWD). Mudge (Mudge AM, 2008) instituted ward-based nursing and interdisciplinary training, as well as patient group sessions.

Population.

Five studies enrolled patients with defined diagnoses (e.g., respiratory illness, COPD, diabetes, pneumonia) (Behnke M, 2003; Eaton T, 2009; Greening NJ, 2014; Mundy et al., 2003; Ozdirenc M, 2004). These studies were more likely to measure and report cardiorespiratory capacity and/or performance outcomes with 3 out of 4 studies demonstrating significant positive impact in measures in this category.

Few studies incorporated sub-group analyses to explore potentially important moderators of intervention effectiveness (Jones CT, 2006; Mudge AM, 2008; Mundy et al., 2003). Mundy’s study of those with community-acquired pneumonia distinguished effect of exercise by participants’ pneumonia severity index (PSI) group (Mundy et al., 2003). Jones reported that greater improvement in mBI scores were observed in the intervention group for those whose admission mBI was low and the effect diminished as the admission mBI score increased (Jones CT, 2006).

Exercise Type.

There was no clear pattern of benefit among studies examining walking plus additional exercise modes (N=7) versus walking alone (N=4). However it is notable that the Courtney study, which used the most comprehensive mode, showed beneficial effects on multiple outcome categories, namely mobility, functional status, utilization, and QoL/patient experience (Courtney M, 2009; Courtney et al., 2012). This study employed a multimodal approach, combining aerobic, resistance, flexibility and balance exercises that extended to home-based intervention for a total of 24 weeks. Post-hospital follow up support and encouragement occurred via nurse telephone calls, weekly in the first month post discharge.

Discussion

While there is broad clinical consensus that immobility among hospitalized older adults contributes to functional decline and other adverse outcomes, evidence of exercise intervention effects is inconsistent. The previously cited Cochrane review (deMorton, Keating, Jeffs, 2007) that included evaluation of 3 exercise-only interventions concluded that “for older patients who are admitted to hospital, exercise sessions may not lead to any difference in function, harms, length of stay in hospital, or whether they go home or to a nursing home or other care facility.” Cumulative evidence from more recent studies on hospital exercise adds little more to this conclusion.

This systematic review summarizes the current state of literature on exercise-only interventions for hospitalized older adults and factors that modify effectiveness, and offers several key observations and recommendations for future work in this area. We found 11 studies examining exercise-only interventions for hospitalized older adults published in the past 15 years. Only 3 of the reviewed studies were conducted in the U.S. despite the fact that more than 1 in 5 Medicare beneficiaries are hospitalized at least once annually and thus are at risk of hospital-associated functional decline. With downward pressure on hospital LOS, especially in the US healthcare system, the ability of short-term exercise interventions to generate rapidly the measurable, positive patient outcomes we seek may be severely challenged. Increasingly older adult patients who are admitted to the inpatient setting are of more advanced age, of higher complexity, in less stable condition (C. M. Boyd et al., 2008; Buurman et al., 2011). Furthermore implications for the inpatient care process are influenced by the use of hospitalists with a focus on readiness for discharge (Yoo et al., 2014).

Overall the data regarding the effectiveness of structured exercise interventions for older adults hospitalized with medical illness were mixed across the five outcome categories that we examined: cardiorespiratory capacity and/or performance, mobility, functional status, healthcare utilization, and quality of life (QoL)/patient experience. Across the 11 studies, significant findings accounted for between 20% (healthcare utilization) to 78% (QOL/patient experience) of total measures within the categories. Functional measure impacts were variable depending on modes of exercise and potentially limited by ceiling or floor effects as described further below. Future studies aiming to understand the true potential value of exercise programs for hospitalized older adults should include patient-centered measures from physical and cognitive health domains including QoL (Courtney M, 2009; Eaton T, 2009). Patient-reported outcomes that evaluate QoL for the older adult are increasingly as meaningful as physiologic measures since they may more effectively reflect patient’s life goals including independence (Tinetti, Fried, & Boyd, 2012). In general, we found that programs that continued in the home-based setting appeared to be more consistently associated with positive results.

The results of this review highlight several challenges and opportunities for the design of future research. Our limited ability to draw firm conclusions based on this review reflects the challenges faced by practitioners and researchers in designing and implementing exercise interventions in acutely hospitalized older adults who may simultaneously be negatively affected by inadequate nutrition, polypharmacy, pain, and sleep deprivation. Patients’ complexity and variability throughout hospitalization likely contributed to the dual challenge of attrition and adherence consistently found among the studies, with drop-out rates of 7% to 32% and adherence rates between 40% and 94%, when reported. Since those who choose not to participate or adhere to an intervention are likely substantially different from those who do, randomized designs with intention to treat analysis are critical to estimate unbiased effect sizes. The low adherence rates also suggest the need for better targeting, tailoring and implementing interventions. Evidence from the Jones study suggests that targeting exercise to those with moderate or severe baseline impairments likely will have the largest effect (Jones CT, 2006); a secondary analysis of pooled data by deMorton supports the targeting strategy for patients who required assistance or supervision to ambulate at the time of hospital admission (De Morton, Jones, et al., 2007). An environment that actively promotes physical activity and patient adherence to exercise participation, established through staff training and telephone home follow-up (Courtney et al., 2012; Greening NJ, 2014; Mudge AM, 2008) may provide more effective, positive interactions than didactic strategies alone. Interdisciplinary, collaborative teams can more effectively influence the culture of patient care. (Yoo et al., 2014).

Selecting appropriate measures for a highly heterogeneous population experiencing a variety of acute stressors is a particular challenge. The Barthel Index, for example, may not be appropriate for patients who are highly robust or very frail prior to admission. Mobility measures (e.g., TUG) can be challenging to carry out among inpatients who have intravenous lines, telemetry monitors, urinary catheters, and are experiencing acute physical symptoms. Utilization measures such as readmission are highly influenced by factors such as social support and co-morbidities, and health system factors and thus may not be sufficiently sensitive to exercise intervention. Evidence suggests that a trade-off relationship exists between LOS and readmission rates that may be particularly relevant for older adults (News, 2015). That said, LOS is an important performance measure for hospital systems; outliers, especially in a heterogeneous patient population, can skew these data (Haines et al., 2015). Studies reporting LOS as an outcome should report whether the study was adequately powered to detect an effect. New measures that take account of premorbid function and the physiologic reserve capacity to meet the demands of exercise during periods of acute illness may be useful (Goldspink, 2005; Hill, Dranka, Zou, Chatham, & Darley-Usmar, 2009; Whitson et al., 2016). Patient or provider-reported measures such as the Activity Measure for Post Acute Care (AMPAC) have been shown to be clinically meaningful, comparable within and across settings, and sensitive to 1, 6, and 12 month follow up (Jette et al., 2014).

A relevant study by Brown and colleagues (Brown et al., 2016) that was published after our search activities were completed provides substantive additional information complementary to our original summation of the literature. This study reinforces the importance of patients’ self-reported measures reported by the current review, especially those that may more effectively reflect older adults’ QoL goals, including maintaining one’s social role in the community.

In the Brown study, implications for recovery of pre-admission mobility level attributable to an in-hospital mobility program are highlighted using self-reported ADL and a community mobility measure, Aging Life-Space Assessment (LSA) (Brown et al., 2016). The LSA is a composite measure based on the level, degree of independence in achieving each level, and frequency of attaining each level of distance traversed during the preceding 4 weeks. At 1-month post hospitalization, patients who had received the intervention (walking up to twice daily) versus those who had received usual care (twice-daily visits by a research assistant; request to document frequency of visitors, both family and health care professionals in a diary) demonstrated a significantly higher LSA, similar to the LSA score at admission. A decline of approximately 10 points was observed in the 1-month LSA score for the usual care group compared to their admission score. Notwithstanding this important QoL outcome, no effect on ADL function was observed.

Our review has several limitations. Risk of bias assessment found 5 studies as unclear/medium risk (de Morton, Keating, Berlowitz, et al., 2007; Eaton T, 2009; Greening NJ, 2014; Hastings et al., 2014; Mudge AM, 2008), and 4 studies as high risk (Behnke M, 2003; Courtney et al., 2012; Mundy et al., 2003; Ozdirenc M, 2004) raising concerns about validity. Studies of low or unclear ROB showed limitations in design and absence of important information. Small study sizes limited the generalizability of findings. Studies were often not adequately powered to detect changes in outcomes. The international nature of these studies is noteworthy. Inherent health system differences among the five countries represented, including local admission, medical treatment, personnel resources, and health systems policies, can affect generalizability of findings.

Conclusion

While there is broad clinical consensus that immobility among hospitalized older adults contributes to functional decline and other adverse outcomes, evidence of 11 exercise-only intervention studies across 5 outcome categories is inconsistent. Larger, well-designed RCTs are needed to further delineate the potential impact and value of hospital-based exercise programs for older adults. Specifically, an ideal study design would incorporate the following elements: a targeted moderate and/or severe risk group (e.g., defined by Modified Barthel Scale), (“Modified Barthel Index (Shah Version): Self-Care Assessment,”) measurement of pre-morbid function, randomization to exercise intervention with a pre-defined intensity, intention to treat, adherence and attrition measures, validated outcome measures without ceiling/floor effects, QoL/patient experience and function after discharge, and subgroups of interest should be identified a priori. Furthermore, it is recommended that future studies measure and report intervention fidelity and enroll adequate numbers of participants to ensure appropriate statistical power to determine intervention effectiveness in light of the considerable risk of attrition in this population and setting.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources:

Dr. Kanach is supported by Advanced Fellowship in Geriatrics, Geriatrics Research, Education and Clinical Center, Durham Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System and the Office of Academic Affiliations.

Dr. Pastva is supported by R01-AG045551–01A1.

Dr. Hall is funded by a Career Development Award from the Rehabilitation Research and Development Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs (2RX001316).

Dr. Pavon is supported by the T. Franklin Williams Scholars Program.

Drs. Pastva, Morey, Hall, and Pavon are supported by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, NIA – P30 – AG028716 and P30-AG028716.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Megan Von Isenburg, and Drs. Cathleen Colon-Emeric and Susan N. Hastings.

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Durham VA Healthcare System.

The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Appendix 1: Search Strategy

Database: PubMed

Date: 3/9/2015

| Search | Query | Items found |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | “Inpatients”[Mesh] OR Inpatient[tiab] OR inpatients[tiab] OR “Hospitalization”[Mesh] OR “Hospitalization”[tiab] OR “Hospitalized”[tiab] OR “Hospitalised”[tiab] OR “Hospitalisation”[tiab] OR “Immobilized”[tiab] OR “Immobilised”[tiab] | 371939 |

| #2 | “Aged”[Mesh] OR “Aged”[tiab] OR “Geriatrics”[Mesh] OR “Geriatrics”[tiab] OR “Geriatric”[tiab] OR “older adult”[tiab] OR “older adults”[tiab] OR “elderly”[tiab] | 2700247 |

| #3 | “Exercise Movement Techniques”[Mesh] OR “Physical Therapy Modalities”[Mesh:NoExp] OR “Exercise Therapy”[Mesh] OR “Exercise Movement Techniques”[Mesh:NoExp] OR “Early Ambulation”[Mesh] OR “Exercise”[Mesh:NoExp] OR “exercise”[tiab] OR “Walking”[Mesh] OR “walk”[tiab] OR “walks”[tiab] OR “walking”[tiab] OR “Muscle Stretching Exercises”[Mesh] OR “Resistance Training”[Mesh] OR “Physical Conditioning, Human”[Mesh] OR mobility[tiab] OR physiotherapy[tiab] OR physical therapy[tiab] OR physical therapist[tiab] OR physical rehabilitation[tiab] OR mobilization[tiab] | 456353 |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | 5129 |

| #5 | (“Comparative Study”[pt] OR “Controlled Clinical Trial”[pt] OR Nonrandom[tiab] OR non-random[tiab] OR nonrandomized[tiab] OR non-randomized[tiab] OR nonrandomized[tiab] OR non-randomised[tiab] OR quasi-experiment*[tiab] OR quasiexperiment*[tiab] OR quasirandom*[tiab] OR quasi-random*[tiab] OR quasi-control*[tiab] OR quasicontrol*[tiab] OR (controlled[tiab] AND (trial[tiab] OR study[tiab])) OR randomized controlled trial[pt] OR randomized[tiab] OR randomised[tiab] OR randomization[tiab] OR randomisation[tiab] OR randomly[tiab] OR trial[tiab] OR groups[tiab]) NOT (animals[mh] NOT humaNot Specified[mh]) NOT (Editorial[ptyp] OR Letter[ptyp] OR Case Reports[ptyp] OR Comment[ptyp]) | 2744728 |

| #6 | #4 AND #5 | 2324 |

| #7 | #6, limited to English and 2000- | 1645 |

Database: Embase

Date: 3/9/2015

| Search | Query | Items found |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | ‘hospital patient’/exp OR ‘hospitalization’/exp OR Inpatient:ab,ti OR inpatients:ab,ti OR Hospitalization:ab,ti OR Hospitalized:ab,ti OR Hospitalised:ab,ti OR Hospitalisation:ab,ti OR Immobilized:ab,ti OR Immobilised:ab,ti | 519614 |

| #2 | ‘aged’/exp OR ‘geriatrics’/exp OR Aged:ab,ti OR Geriatrics:ab,ti OR Geriatric:ab,ti OR ‘older adult’:ab,ti OR ‘older adults’:ab,ti OR elderly:ab,ti | 2651541 |

| #3 | ‘kinesiotherapy’/exp OR ‘physiotherapy’/de OR ‘exercise’/exp OR ‘mobilization’/exp OR ‘walking’/exp OR walk:ab,ti OR walks:ab,ti OR walking:ab,ti OR mobility:ab,ti OR physiotherapy:ab,ti OR ‘physical therapy’:ab,ti OR ‘physical therapist’:ab,ti OR ‘physical rehabilitation:ab,ti’ OR mobilization:ab,ti | 590549 |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | 5840 |

| #5 | (‘comparative study’/exp OR ‘controlled clinical trial’/exp OR ‘randomized controlled trial’/exp OR ‘crossover procedure’/exp OR ‘double blind procedure’/exp OR ‘single blind procedure’/exp OR random* OR factorial* OR crossover* OR cross NEAR/1 over* OR placebo* OR doubl* NEAR/1 blind* OR singl* NEAR/1 blind* OR assign* OR allocat* OR volunteer* OR Nonrandom OR non-random OR nonrandomized OR non-randomized OR nonrandomized OR non-randomised OR quasi NEAR/1 experiment* OR quasiexperiment* OR quasirandom* OR quasi NEAR/1 random* OR quasi NEAR/1 control* OR quasicontrol* OR (controlled AND (trial OR study))) NOT (‘case report’/exp OR ‘case study’/exp OR ‘editorial’/exp OR ‘letter’/exp OR ‘note’/exp) | 6197281 |

| #6 | #4 AND #5 | 2601 |

| #7 | #6 AND [humaNot Specified]/lim AND [english]/lim AND [embase]/lim NOT [medline]/lim | 395 |

Database: CINAHL

Date: 3/9/2015

| Search | Query | Items found |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | (MH “Inpatients”) OR (MH “Hospitalization+”) OR TI ( Inpatient OR inpatients OR Hospitalization OR Hospitalized OR Hospitalised OR Hospitalisation OR Immobilized OR Immobilised ) OR AB ( Inpatient OR inpatients OR Hospitalization OR Hospitalized OR Hospitalised OR Hospitalisation OR Immobilized OR Immobilised ) | 150702 |

| #2 | (MH “Aged+”) OR (MH “Geriatrics”) OR TI ( Aged OR Geriatrics OR Geriatric OR “older adults” OR elderly ) OR AB ( Aged OR Geriatrics OR Geriatric OR “older adults” OR elderly ) | 580202 |

| #3 | (MH “Therapeutic Exercise+”) OR (MH “Physical Therapy”) OR (MH “Early Ambulation”) OR (MH “Exercise+”) OR TI ( exercise OR walk OR walks OR walking OR mobility OR physiotherapy OR “physical therapy” OR “physical therapist” OR “physical rehabilitation” OR mobilization ) OR AB ( exercise OR walk OR walks OR walking OR mobility OR physiotherapy OR “physical therapy” OR “physical therapist” OR “physical rehabilitation” OR mobilization) | 157220 |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | 2849 |

| #5 | (PT randomized controlled trial) OR (MH “Randomized Controlled Trials”) OR (MH “Comparative Studies”) OR (MH “Nonrandomized Trials”) OR (MH “Clinical Trials”) OR TI (Nonrandom OR non-random OR nonrandomized OR non-randomized OR nonrandomised OR non-randomised OR quasi-experiment* OR quasiexperiment* OR quasirandom*OR quasi-random* OR quasi-control* OR quasicontrol* OR randomized OR (controlled AND (trial OR study)) OR randomised OR randomization OR randomisation OR randomly OR trial) OR AB (Nonrandom OR non-random OR nonrandomized OR non-randomized OR nonrandomised OR non-randomised OR quasi-experiment* OR quasiexperiment* OR quasirandom*OR quasi-random* OR quasi-control* OR quasicontrol* OR randomized OR (controlled AND (trial OR study)) OR randomised OR randomization OR randomisation OR randomly OR trial) | 337446 |

| #6 | #4 AND #5 | 859 |

| #7 | #6, limited to English and 2000- | 770 |

Appendix 2: Risk of Bias Assessment by Setting

| Inpatient Hospital Setting | Inpatient Hospital to

Home/Community Setting |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jones, 2006 | deMorton, 2007 | Mudge, 2008 | Hastings, 2014 | Mundy, 2003 | Ozdirenc, 2003 | Siebens, 2000 |

Courtney,2009 Courtney,2012 |

Greening,2014 | Eaton, 2008 | Behnke, 2003 | ||

| + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | ? | + | ? | Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? | |

| + | ? | + | − | − | ? | + | ? | ? | + | ? | Was allocation adequately concealed? | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Was knowledge of the allocation intervention adequately prevented during the study? | |

| + | ? | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | ? | ? | Was knowledge of the allocation intervention adequately prevented from the outcome assessors? | |

| + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | ? | Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? | |

| + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? | |

| + | + | + | + | ? | ? | + | ? | + | + | ? | Are reports of the study free from other bias due to problems not covered above? | |

| + | ? | ? | ? | − | − | + | − | ? | ? | − | Overall | |

For overall score, low ROB required random sequencing, allocation concealment, and blinding in order to be scored low risk with no other important concerns; unclear ROB was assigned if 1 or 2 domains were scored not clear or not done; high ROB was assigned if >2 domains were scored not clear or not done.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Note: This article will be published in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. This article appears here in its accepted, peer-reviewed form; it has not been copy edited, proofed, or formatted by the publisher.

References

- Anderson-Hanley C, Nimon JP, & Westen SC (2010). Cognitive health benefits of strengthening exercise for community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 32(9), 996–1001. doi: 10.1080/13803391003662702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anpalahan M, & Gibson SJ (2008). Geriatric syndromes as predictors of adverse outcomes of hospitalization. Internal Medicine Journal, 38(1), 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann S, Finger C, Huss A, Egger M, Stuck AE, & Clough-Gorr KM (2010). Inpatient rehabilitation specifically designed for geriatric patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ, 340, c1718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baztan JJ, Suarez-Garcia FM, Lopez-Arrieta J, Rodriguez-Manas L, & Rodriguez-Artalejo F (2009). Effectiveness of acute geriatric units on functional decline, living at home, and case fatality among older patients admitted to hospital for acute medical disorders: meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed), 338, b50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean JF, Vora A, & Frontera WR (2004). Benefits of exercise for community-dwelling older adults. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 85(7 Suppl 3), S31–42; quiz S43–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke MJR, Magnussen H (2003). Clinical benefits of a combined hospital and home-based exercise programme over 18 months in patients with severe COPD. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease. Archivio Monaldi per Le Malattie Del Torace, 59(1), 44–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CM, Landefeld CS, Counsell SR, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Kresevic D, … Covinsky KE (2008). Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56(12), 2171–2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CM, Landefeld CS, Counsell SR, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Kresevic D, … Covinsky KE (2008). Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56(12), 2171–2179. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02023.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CJ, Foley KT, Lowman JD Jr., MacLennan PA, Razjouyan J, Najafi B, … Allman RM (2016). Comparison of Posthospitalization Function and Community Mobility in Hospital Mobility Program and Usual Care Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, de Haan RJ, Abu-Hanna A, Lagaay AM, Verhaar HJ, … de Rooij SE (2011). Geriatric conditions in acutely hospitalized older patients: prevalence and one-year survival and functional decline. PloS One, 6(11), e26951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. (Vol. 5.1.0).

- Counsell SR, Holder CM, Liebenauer LL, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Kresevic DM, … Landefeld CS (2000). Effects of a multicomponent intervention on functional outcomes and process of care in hospitalized older patients: A randomized controlled trial of Acute Care for Elders (ACE) in a community hospital. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(12), 1572–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney MEH, Chang A, Parker A, Finlayson K, Hamilton K. (2009). Fewer Emergency Readmissions and Better Quality of Life for Older Adults at Risk of Hospital Readmission: A Randomized Controlled Trial to Determine the Effectiveness of a 24-Week Exercise and Telephone Follow-Up Program. JAGS, 57(3), 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney MD, Edwards HE, Chang AM, Parker AW, Finlayson K, Bradbury C, & Nielsen Z (2012). Improved functional ability and independence in activities of daily living for older adults at high risk of hospital readmission: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(1), 128–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Counsell SR, Stewart AL, Kresevic D, … Landefeld CS (2003). Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51(4), 451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, & Johnston CB (2011). Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure”. JAMA, 306(16), 1782–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creditor MC (1993). Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Annals of Internal Medicine, 118(3), 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Morton NA, Jones CT, Keating JL, Berlowitz DJ, MacGregor L, Lim WK, … Brand CA (2007). The effect of exercise on outcomes for hospitalised older acute medical patients: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Age and Ageing, 36(2), 219–222. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Morton NA, Keating JL, Berlowitz DJ, Jackson B, & Lim WK (2007). Additional exercise does not change hospital or patient outcomes in older medical patients: a controlled clinical trial. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 53(2), 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Morton NA, Keating JL, & Jeffs K (2007). Exercise for acutely hospitalised older medical patients. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews(1), CD005955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton TYP, Fergusson W, Seng I, O’Kane F, Good N, Rhodes L, Poole P, Kolbe J. (2009). Does early pulmonary rehabilitation reduce acute health-care utilization in COPD patients admitted with an exacerbation? A randomized controlled study. Respirology, 14, 230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleck SJ, Bustamante-Ara N, Ortiz J, Vidan MT, Lucia A, & Serra-Rexach JA (2012). Activity in GEriatric acute CARe (AGECAR): rationale, design and methods. BMC Geriatrics, 12, 28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldspink DF (2005). Ageing and activity: their effects on the functional reserve capacities of the heart and vascular smooth and skeletal muscles. Ergonomics, 48(11–14), 1334–1351. doi: 10.1080/00140130500101247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greening NJ WJ, Hussain SF, Harvey-Dunstan TC, Bankart MJ, Chaplin EJ, Vincent EE, Chimera R, Morgan MD, Singh SJ, Steiner MC, LNR C. (2014). An early rehabilitation intervention to enhance recovery during hospital admission for an exacerbation of chronic respiratory disease: randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 349: g4315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines TP, O’Brien L, Mitchell D, Bowles KA, Haas R, Markham D, … Skinner EH (2015). Study protocol for two randomized controlled trials examining the effectiveness and safety of current weekend allied health services and a new stakeholder-driven model for acute medical/surgical patients versus no weekend allied health services. Trials, 16, 133. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0619-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings SN, Sloane R, Morey MC, Pavon JM, & Hoenig H (2014). Assisted early mobility for hospitalized older veterans: preliminary data from the STRIDE program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62(11), 2180–2184. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC BG, Engeland CG, Marucha PT, Masi CM, Cacioppo JT. (2005). Stress, aging, and resilience: Can accrued wear and tear be slowed? Canadian Psychology, 46(3), 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hill BG, Dranka BP, Zou L, Chatham JC, & Darley-Usmar VM (2009). Importance of the bioenergetic reserve capacity in response to cardiomyocyte stress induced by 4-hydroxynonenal. Biochemical Journal, 424(1), 99–107. doi: 10.1042/bj20090934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulya TD, Sevi YS, Serap A, & Ayse OE (2015). Factors affecting the benefits of a six-month supervised exercise program on community-dwelling older adults: interactions among age, gender, and participation. J Phys Ther Sci, 27(5), 1421–1427. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr., Baker DI, Leo-Summers L, & Cooney LM Jr. (2000). The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital Elder Life Program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(12), 1697–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, & Jette AM (2014). Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Physical Therapy, 94(3), 379–391. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CT LA, MacGregor L, Brand CA. (2006). A randomised controlled trial of an exercise intervention to reduce functional decline and health service utilisation in the hospitalised elderly. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 25(3), 126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch BJ, Dabney BW, & Lee S (2013). Safety of mobilizing hospitalized adults: review of the literature. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 28(2), 162–168. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e31827c10d5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinpell RM FK, Jennings BM. (2008). Advances in Patient Safety Reducing Functional Decline in Hospitalized Elderly. (RG H Ed.). Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortebein P (2009). Rehabilitation for hospital-associated deconditioning. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation / Association of Academic Physiatrists, 88(1), 66–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortebein P, Symons TB, Ferrando A, Paddon-Jones D, Ronsen O, Protas E, … Evans WJ (2008). Functional impact of 10 days of bed rest in healthy older adults. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 63(10), 1076–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosse NM, Dutmer AL, Dasenbrock L, Bauer JM, & Lamoth CJ (2013). Effectiveness and feasibility of early physical rehabilitation programs for geriatric hospitalized patients: a systematic review. BMC Geriatrics, 13, 107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, Fortinsky RH, & Kowal J (1995). A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. The New England journal of medicine, 332(20), 1338–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS CD, Becker B (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney JE, Sager MA, & Jalaluddin M (1998). New walking dependence associated with hospitalization for acute medical illness: incidence and significance. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 53(4), M307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modified Barthel Index (Shah Version): Self-Care Assessment.

- Mudge AM GA, Mgt MA, Cutler AJ (2008). Exercising Body and Mind: An Integrated Approach to Functional Independence in Hospitalized Older People. JAGS, 56(4), 630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy LM, Leet TL, Darst K, Schnitzler MA, & Dunagan WC (2003). Early mobilization of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest, 124(3), 883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, Duncan PW, Judge JO, King AC, … American Heart A (2007). Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation, 116(9), 1094–1105. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- News KH (2015). Health Law Penalties May Be Skewing Hospital Readmission Rates for Medicare Patients. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdirenc MKG, Guntekin R (2004). The acute effects of in-patient physiotherapy program on functional capacity in type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 64, 167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penedo FJ, & Dahn JR (2005). Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 18(2), 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, Connolly B, Ratnayake G, Chan P, … Montgomery HE (2013). Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. JAMA, 310(15), 1591–1600. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager MA, Franke T, Inouye SK, Landefeld CS, Morgan TM, Rudberg MA, … Winograd CH (1996). Functional outcomes of acute medical illness and hospitalization in older persons. Archives of Internal Medicine, 156(6), 645–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddarth D, Siddarth P, & Lavretsky H (2014). An observational study of the health benefits of yoga or tai chi compared with aerobic exercise in community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(3), 272–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebens H, Aronow H, Edwards D, & Ghasemi Z (2000). A randomized controlled trial of exercise to improve outcomes of acute hospitalization in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(12), 1545–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinetti ME, Fried TR, & Boyd CM (2012). Designing health care for the most common chronic condition--multimorbidity. JAMA, 307(23), 2493–2494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace BC SK, Brodley CE, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. (2012). Deploying an interactive machine learning system in an evidence-based practice cneter: abstrackr. Proceedings of the ACM Intrnational Health Informatics Symposium, 819–824. [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, Yeh CJ, Wang CW, Wang CF, & Lin YL (2011). The health benefits following regular ongoing exercise lifestyle in independent community-dwelling older Taiwanese adults. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 30(1), 22–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2010.00441.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitson HE, Duan-Porter W, Schmader KE, Morey MC, Cohen HJ, & Colon-Emeric CS (2016). Physical Resilience in Older Adults: Systematic Review and Development of an Emerging Construct. Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 71(4), 489–495. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo JW, Seol H, Kim SJ, Yang JM, Ryu WS, Min TD, … Kim S (2014). Effects of hospitalist-directed interdisciplinary medicine floor service on hospital outcomes for seniors with acute medical illness. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 14(1), 71–77. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]