Abstract

Studies have often described a specific model or models of permanent supportive housing, yet few studies have systematically examined what services are typically offered to PSH tenants in any given service system and how those services are offered. Using telephone surveys from 23 PSH agency supervisors and qualitative data collected from 11 focus groups with 60 frontline providers and 17 individual interviews with supervisors from a subset of surveyed agencies – all of which were completed between July 2014 and December 2015, the goal of this study is to better understand what services are being offered in PSH organizations located in Los Angeles and what barriers frontline providers face in delivering these services. Survey findings using statistical frequencies suggest the existence of robust support services for a high-needs population and that single-site providers may offer more services than scatter-site providers. Qualitative thematic analysis of interview and focus group transcripts suggests services may be less comprehensive than they appear. If PSH is to be regarded as an intervention capable of more than “just” ending homelessness, further consideration of the provision of supportive services is needed.

Keywords: Permanent supportive housing, Homelessness, Frontline providers, Mixed methods, Homelessness, Housing First, Case management, Mixed-methods

Permanent supportive housing (PSH), in conjunction with the Housing First approach is regarded as an evidence-based intervention to end homelessness (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016; U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, 2010) and has been credited with a decline in the number of chronically homeless adults in the United States since 2007 (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2015). PSH has become an umbrella term that refers to multiple combinations of housing and supportive services for homeless adults (U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, 2010) that can be complicated given different funding sources, regulatory oversight, and possible configurations. For example, in the literature the definitions of the delivery of supportive services in PSH are varied. Services can range from low intensity, such as case management, to high intensity, such as assertive community treatment, which is an evidence-based, multidisciplinary, team-based intervention (Aubry et al., 2015; Matejkowski & Draine, 2009). Supportive services may refer to health or psychosocial interventions or both, can be located off-site or collocated with housing, and can be delivered in a clinic or at home. Finally, although U.S. federal policy promotes the use of Housing First in all PSH programs for homeless adults (i.e. low-barrier access to housing, consumer driven services, harm reduction), not all PSH program necessarily follow a Housing First philosophy (Padgett, Henwood, & Tsemberis, 2016).

PSH also subsumes an earlier distinction between “supportive” and “supported” housing, where the former referred to a congregate living situations with on-site supervision that did not embrace a housing first approach and the latter referred to independent living in scatter-site apartments with community-based supports that initially defined housing first (Ridgway & Zipple, 1990; Tsemberis & Eisenberg, 2000). Today, PSH using a housing first approach refers to either single-site housing (i.e., one building that is designated for formerly homeless tenants, which may have congregate/shared living arrangements or independent apartments (Collins, Malone, & Clifasefi, 2013) or scatter-site housing units rented throughout a neighbourhood from private landlords (Tsemberis, Gulcur, & Nakae, 2004). PSH providers may differently match housing and services (e.g., single-site programs providing intensive, in-home services and scatter-site programs relying on clinic-based operations) or may combine multiple types of housing and service approaches in one organization (Foster, LeFauve, Kresky-Wolff, & Rickards, 2010; Kresky-Wolff, Larson, O’Brien, & McGraw, 2010; McGraw et al., 2010).

Few studies have systematically examined what services are typically offered to PSH tenants in any given service system and how those services are offered (e.g., on-site versus off-site). A study of 93 programs across California found significant variation in fidelity to housing first and the array of services offered, due to numerous factors including the specific county system in which the program was located (Gilmer, Katz, Stefancic, & Palinkas, 2013; Gilmer, Stefancic, Henwood, & Ettner, 2015). Other studies of PSH that have considered variation in service delivery have been part of experimental designs to test Housing First rather than reflecting typical programmatic differences (Aubry et al., 2015). Although there is not a one-size-fits-all model of PSH, the literature suggests that how PSH is implemented can affect housing retention (Gilmer, Stefancic, Sklar, & Tsemberis, 2013; Goering et al., 2016; Watson, Orwat, Wagner, Shuman, & Tolliver, 2013), which includes the availability of comprehensive services that would also likely affect health and well-being outcomes for a population that has experienced a lifetime of cumulative adversity (Padgett, Smith, Henwood, & Tiderington, 2012), carries a significant disease burden (Hwang et al., 2001), and experiences mortality rates 3 to 4 times that of the general population (O’Connell, 2005).

The goal of this study is to better understand how supportive services are being offered in PSH across a community sample of organizations in Los Angeles, California and whether there appears to be differences between single- and scatter-site settings. In addition, we examine what barriers, if any, frontline providers face in delivering these services. To achieve this goal, this study uses both quantitative data from 23 telephone surveys with agency supervisors about the types of housing and services that are offered and qualitative data collected from 11 focus groups with 60 frontline providers and 17 individual interviews with supervisors from a subset of surveyed agencies. Because the population served by PSH often has high needs that require multiple health and psychosocial services that may be difficult for a single organization to provide (Henwood, Weinstein, & Tsemberis, 2011), providers were asked to distinguish between services that are made available to residents through their PSH organization and those coordinated with an outside agency. This study seeks to answer specific questions: Are programs able to provide comprehensive services, either in-house or in collaboration with community partners? Are there differences between single- and scatter-site PSH organizations? How are providers working to overcome barriers that may impede clients from receiving the comprehensive services that they need?

Methods

This study relies on data from a larger project funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse that is investigating changes in social networks and health risk behaviours as adults aged 39 or older transition from homelessness to PSH (Wenzel, 2014). The study takes place in Los Angeles County, which has the largest unsheltered homeless population in the United States, with a large concentration of the population located in the downtown Skid Row area (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2015). The larger study recruited participants from 26 agency partners located in a 20-mile radius of downtown Los Angeles or in the Long Beach area, representing the vast majority of PSH providers for adults in Los Angeles County. Quantitative data for this study were drawn from telephone surveys conducted with agency supervisors at 23 out of the 26 PSH partnering agencies; two agencies were excluded because they largely provided housing subsidies rather than support services and one agency did not respond to the survey request. Qualitative interviews with 17 supervisory staff members and 11 focus groups with 60 frontline staff members were conducted with providers from a subset of the 23 partner agencies and analysed to better understand survey responses, thus reflecting a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design (Cresswell & Plano Clark, 2011). Both quantitative and qualitative data for this study were collected between July 2014 and December 2015, and were included in the design of the larger study. All questions and procedures were approved by the affiliated institutional review board.

Survey design

Agency staff who helped coordinate recruitment for the larger study and who had knowledge of overall agency operations were asked to participate in a telephone administered survey that assessed agency characteristics including the proportion of single- versus scatter-site units, number of formerly homeless residents, average number of residents in a case manager’s caseload, specialty populations served, and services offered. Services in each agency were assessed through several questions pertaining to the type of service offered (e.g., mental health care, physical health care, life skills, and employment; 13 different services) provided in a list derived from existing literature (Malone, Collins, & Clifasefi, 2015; Mares & Rosenheck, 2011). Respondents were asked whether services were delivered by the agency in-house or through a partnering agency and whether they were delivered on-site or off-site. For scatter-site services, on-site is defined as services delivered in the resident’s home, whereas for single-site agencies, this is defined as either services provided in an on-site clinic or at the resident’s home. The telephone survey was piloted and revised for clarity. An electronic copy of telephone survey procedures was sent to the telephone survey respondents prior to conducting the survey and informed consent was obtained verbally. Written informed consent was waived since respondents were not asked to provide identifying information and the nature of the questions was not deemed to be sensitive. Statistical frequencies were generated in SAS version 9.4.

Qualitative component

Purposive sampling (Patton, 2002) was used to select a subsample of 11 PSH agencies that either contributed larger portions of participant referrals to the parent study or served special populations, such as veterans or women. Individual interviews, which focused on organizational policies and procedures that affect service delivery, were then conducted with 17 staff members who held a supervisory position at these 11 agencies. Supervisors were purposively selected to gather information related to political and organizational factors that affect service delivery from supervisors in various supervisory roles (e.g. services, retention, operations). Individual interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. 11 focus groups were conducted with 60 frontline providers, namely case managers, program managers, and leasing office employees. Agencies were asked to arrange for up to 10 frontline providers to take part in the focus groups. An average of five providers participated in each focus group (range: 3–11), with groups lasting approximately 1 hour. Focus group discussion was facilitated via a semi structured interview guide; two members of the investigative team asked questions and provided hypothetical scenarios related to service provision in PSH. Both interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Written informed consent was waived as no identifying information of participants was collected. Participants were asked to refrain from providing identifying information and were assured that all identifying information, including individual statements or views from the organization would be removed from transcription and would remain confidential. Participating supervisors received a $25 incentive for their time, and frontline staff received a $20 incentive for participation. Phone interview participants were not compensated.

Focus group and individual interview transcripts were entered into ATLAS.ti qualitative software and analysed using constant comparative methods (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) that involved a process of both open and template-style coding. Open coding refers to a technique in which codes are derived inductively from the data (Charmaz, 2006), whereas a template approach involves using predetermined codes in an area of interest and then organizing and coding transcripts based on these codes (Crabtree & Miller, 1999). For example, template codes include provider roles, housing retention, and care coordination. Open codes include rules and regulation, focus on housing stability, and hands-on versus hands-off approaches. Initially, two authors independently coded three transcripts and then compared results to reach consensus regarding the list of codes. They then independently coded all transcripts using the agreed-upon codes and compared the appropriateness of assigning a particular code to a given passage or quote. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus, resulting in an initial set of themes identified by reviewing coded material. For purposes of this study, themes are selected that shed light on survey findings.

Results

Survey findings

As shown in Table 1, the 23 participating agencies offer a range of services. All agencies reported offering case management, which is available on-site in most cases. All but two agencies indicated offering mental health services and primary health care, although most rely on an outside primary care provider and one third rely on an outside mental health agency. Education and HIV prevention programs are the service least commonly offered. The majority of agencies indicated that most services are available on-site, with education, job, and legal services being an exception.

TABLE 1.

Services Offered and Proportion of Providers Relying on Outside Agencies and Providing Services On-Site (N = 23)

| Service | Services Offered Within PSH |

Services Coordinated With Outside Agency |

Services Available On-Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Case management | 23 (100) | 0 (0) | 21 (96) |

| Mental health treatment | 21 (91) | 7 (33) | 13 (62) |

| Substance use treatment | 19 (83) | 4 (21) | 12 (63) |

| Trauma servicesa | 17 (74) | 1 (6) | 11 (65) |

| Primary health care | 21 (91) | 13 (62) | 11 (52) |

| Education services | 9 (39) | 4 (44) | 3 (33) |

| Job services | 15 (65) | 4 (27) | 6 (40) |

| Life skills | 22 (96) | 0 (0) | 17 (77) |

| Support groupsb | 18 (78) | 0 (0) | 13 (72) |

| Social groups | 15 (65) | 0 (0) | 10 (67) |

| Clothing assistance | 14 (61) | 2 (14) | 8 (57) |

| Food assistance | 15 (65) | 0 (0) | 11 (73) |

| Exercise classes | 14 (61) | 0 (0) | 10 (57) |

| HIV prevention | 13 (57) | 1 (11) | 9 (69) |

| Legal services | 12 (52) | 10 (83) | 4 (33) |

| Transportation services | 18 (78) | 0 (0) | 14 (78) |

| SS application assistancec | 20 (87) | 0 (0) | 16 (80) |

| Art classes | 15 (65) | 0 (0) | 12 (80) |

Note.—The 1st column represents the proportion of agencies that indicated a service was made available to PSH clients. The 2nd column indicates proportion of agencies that relied solely on outside agency partnerships to provide the service, instead of delivering the service themselves. The 3rd column reflects the proportion of agencies that provided the service on-site at the PSH location as opposed to a service location off-site. Proportions in the 2nd and 3rd columns are relative to only agencies that reported offering the service in the 1st column rather than the full sample.

Examples include trauma-informed care and treatment for domestic violence.

Examples include Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous.

Refers to assistance with an application to receive Social Security benefits.

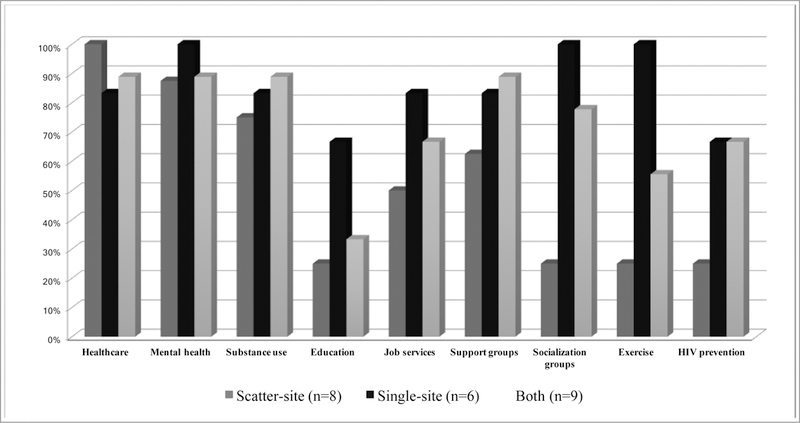

Of the 23 agencies interviewed in the telephone survey, eight provide only scatter-site housing, six provide only single-site housing, and nine provide a mixture of both. Although the average number of residents served by these three types of providers varies (M = 310.5, SD = 248.0; M = 1,161.7, SD = 850.7; and M = 733.0, SD = 1,073.2, respectively), the average caseload is 35.5 (SD = 24.8) residents per provider and is similar across the three types of agencies (M = 33.9, SD = 29.2; M = 38.8, SD = 19.3; and M = 34.8, SD = 26.4, respectively). Figure 1 shows that across housing models there were high rates of health care, mental health, and substance abuse services but also that programs that provided scatter-site as compared to single-site housing appeared to provide fewer educational services (25% versus 67%), job services (50% versus 83%), support groups (63% versus 83%), social skills groups (25% versus 100%), exercise (25% versus 100%), and HIV prevention (25% versus 67%).

FIGURE 1.

Services available in permanent supportive housing (PSH) programmes that provide scatter-site, single-site, or both.

Qualitative findings

Despite the availability of comprehensive services in PSH, qualitative analysis reveal that providers perceive multiple barriers to effective service delivery, including a patchwork services approach, relying on outside agencies, and limited provider capacity.

Patchwork services approach

As one provider expressed, “Services, in many ways, are kind of patchworked together.” Differences in housing subsidy programs are seen as contributing to this patchwork approach, with one provider explaining, “So for VASH [Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing] it looks one way, for a Section 8 it looks another way. And there’s, depending on who the contract is with or if there’s a contract, it’ll be different things.” Having to contract with multiple outside service providers makes consistent access to service difficult. As one provider explained, “We do have some buildings where we are in partnership with some sort of health agency. And it depends. Another building, as well, we have like a clinic on site in the building. But right now we do have some other buildings that are not connected.” Providers also noted that newer buildings are more likely to have these services, which are more easily incorporated through recent design and planning. “Some of the older buildings don’t have all of those wraparound services.”

Variation or inconsistency in the distance between residents’ homes and locations where health services could be accessed was regarded as problematic. “Even though it might be a block away, a block away on Skid Row is huge, so someone that is in a building where they don’t have on-site services, they may or may not make it to the buildings that have services.” Case managers agreed that having more on-site services will likely increase residents’ use of appropriate care. “Service-enriched housing where you have these things available and the person can just come out of their door and go to it probably will have more participation than if the person had to go through extraordinary things to go to it.” Some providers offer transportation to and from off-site services, but acknowledged this is time consuming and could interfere with managing other cases: “I have a lady right now that I spent 10 to 15 hours with her, or more, this past week, driving her.”

Relying on outside agencies

Having a patchwork service approach also requires increased communication with providers at other agencies, and as one participant expressed, “a lot of the time the third parties don’t even want to communicate with you.” Having a formalized institution relationship, such as a memorandum of understanding, is viewed as helpful, but some providers said lack of communication with outside providers is “just because they don’t think you’re worth dealing with,” given the population being served.

Some providers said they would prefer directly delivering services rather than relying on outside providers if they had adequate training. For example, case managers in one focus group agreed that if they had skills to deliver harm reduction interventions or motivational interviewing, they could provide substance use treatment when appropriate, rather than solely depending on referrals. “A lot of trainings are free, but we haven’t come across a free motivational interviewing one. That is a tool that I know I would really benefit from.” Providers indicated some of the reasons they lack these skills include a lack of affordable trainings, limited time to attend such trainings, and the absence of relevant information in trainings. “[Harm reduction trainings] talk about drugs the whole time, but they don’t actually talk about, like, hands-on techniques.”

Limited provider capacity

In addition to limited agency resources that make staff training and development challenging, large caseloads are viewed as problematic. Providers often struggle with whether to focus on fewer residents with high service needs or meeting program guidelines regarding frequency of interactions with all residents. One participant described this concern by stating, “We can’t keep building and building and building on the caseloads when people aren’t yet stable.” As a result, many providers agreed that their primary job is to oversee residents’ retention of housing. As one participant explained, “As a provider of permanent supportive housing … the primary purpose is to support the tenants with their having the capacity or ability to keep that key, if you will, to be able to maintain their tenancy.” Retention services are described as communicating with property managers, assisting with social service assistance applications, helping to resolve landlord disputes, and managing rental payments, with less focus on health and intensive recovery services. Although providers are interested in providing such services, most said they are sceptical that this will ever be a possibility because it would require “smaller caseloads. That’s wishful thinking; ain’t gonna happen.”

Discussion

The findings from this study present a mixed picture regarding the availability of support services in PSH. On one hand, most PSH programs in Los Angeles County appear to offer critical services including case management, primary and mental health care, and substance abuse treatment, although the lack of HIV prevention services is noteworthy given this high-risk population (Brown et al., 2012; Wenzel, Tucker, Elliott, & Hambarsoomians, 2007). These programs also appear to have the ability to provide on-site services in either single- or scatter-site housing, with a significant portion of the sample indicating that they provide both types of housing, which is not typically reported in experimental studies of PSH (Aubry et al., 2015; Larimer et al., 2009; Tsemberis et al., 2004). Still, organizations that provide scattered-site housing appear to provide fewer services such as education, socialization groups, and exercise, which may reflect the fact that traveling to deliver such services is time intensive and may compromise organizational capacity to deliver comprehensive care especially given large caseloads (Matejkowski & Draine, 2009). This may suggestion a tension in some fidelity standards between providing scattered-site housing and comprehensive services that can meet tenants’ needs (Gilmer et al., 2013).

Although the survey findings appear to suggest that robust support services exist for this high-needs population especially within single-site housing providers, qualitative findings from interviews with PSH staff members suggest otherwise. That is, although services may be available to some residents, PSH staff members indicated that services are not necessarily routinely accessible to all residents depending on factors such as housing location or different provider contracts. In addition, the availability of services does not imply that they are integrated or even well-coordinated, which is especially important for individuals with complex health and social needs (Craig, Eby, & Whittington, 2011). PSH program staff members indicated that even communicating with outside providers is often challenging, which may reflect underlying discrimination and stigma towards homeless adults (Wen, Hudak, & Hwang, 2007).

It is important to note that although taken in isolation, quantitative and qualitative results may suggest contradictory findings, the strength of using mixed methods (Cresswell & Plano Clark, 2011) is that when taken together, the findings provide a more complete assessment of the availability of services in PSH and should be considered when measuring program fidelity. Similarly, qualitative findings indicate that an average caseload of approximately 36 residents per staff member may prohibit PSH providers from focusing on anything more than keeping people housed. Although this may be regarded as the ultimate marker of success for PSH, it misses the importance of delivering person-centered care that is a housing first fidelity standard (Gilmer et al., 2013) and precludes the potential of PSH to serve as an effective platform to address the lifetime cumulative adversity and health disparities experienced by adults who have experienced chronic homelessness (Henwood, Cabassa, Craig, & Padgett, 2013). Lack of comprehensive services may also explain why previous studies of PSH have found lack of improvement outcomes such as community integration (Tsai, Mares & Rosenheck, 2012) and substance use (Somers, Moniruzzaman & Palepu, 2015). Whether services are available remains a different question than whether individuals access services (Padgett, Henwood, Abrams, & Davis, 2008), which underscores the importance of patient-centered service design and delivery (Bao, Casalino, & Pincus, 2013).

In addition to using a mixed-methods approach in which the qualitative data provide important context and expand on the survey findings (Palinkas, Horwitz, Chamberlain, Hurlburt, & Landsverk, 2011), a strength of this study is its inclusion of a large community sample of PSH programs to better understand real-world service delivery (Padgett, 2012) that does not readily fit with models of PSH described elsewhere in the literature (Collins et al., 2013; Tsemberis et al., 2004). However, one of the main limitations of this study is that the sample is specific to Los Angeles County; it is unclear the extent to which this reflects how PSH is implemented elsewhere. Further, the survey instrument addresses overall organizational operations and does not differentiate among multiple programs in one agency that may operate differently. Response bias related to overstating the availability of services is also possible. Finally, the qualitative findings are based on staff members employed by the PSH recruitment agencies and do not include many providers who may be considered part of PSH but are employed by other agencies, particularly medical, mental, and behavioural health treatment specialists. Although the focus groups and interviews were anonymous, there may be an under- or over-reporting of services and capacities. Nevertheless, multiple strategies of rigor for qualitative methods were used, including co-coding, peer team debriefing, and triangulation of multiple sources of data (Padgett, 2012).

Conclusion

Whether PSH programs can effectively serve as the locus for comprehensive, integrated services has not been established, yet PSH has been included in healthcare redesign efforts to create a locus for health care delivery for unstably housed or homeless adults with complex health and social needs (Doran, Misa, & Shah, 2013). Findings from this study suggest several considerations if PSH is to be regarded as an intervention capable of more than “just” ending homelessness. First, PSH programs may need increased capacity to deliver services rather than trying to coordinate with outside providers. Second, current resident-to-staff ratios in PSH should be reviewed to ensure providers have the capacity to do more than focus on housing retention. Third, staff development and training could be an important mechanism to consolidate some services in-house rather than always needing to refer individuals to outside providers. Although specific PSH programs have incorporated such considerations (Weinstein et al., 2013), findings from this study suggest they represent an exception rather than the norm. Larger system-level work that includes a direct source of funding for both the housing and service components of PSH could have a direct impact on the types of community programs that participated in this study.

What is known about this topic:

-

-

Supportive housing effectively addresses homelessness

-

-

There are different models of supportive housing.

-

-

Barriers exist to delivering adequate supportive services

What this paper adds:

-

-

Systematic assessment of what and how services are offered within a community sample

-

-

Despite offering comprehensive services many programs experience gaps in services

-

-

Single-site housing programs appear to offer more services than scatter-site programs

Acknowledgements:

This work was funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse, 1R01DA036345-01A1

Footnotes

Disclaimers: None

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Aubry T, Tsemberis S, Adair CE, Veldhuizen S, Streiner D, Latimer E, … Goering P (2015). One-year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of Housing First with ACT in five Canadian cities. Psychiatric Services, 66, 463–469. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Casalino LP, & Pincus HA (2013). Behavioral health and health care reform models: Patient-centered medical home, health home, and accountable care organization. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 40, 121–132. 10.1007/s11414-012-9306-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Kennedy DP, Tucker JS, Wenzel SL, Golinelli D, Wertheimer SR, & Ryan GW (2012). Sex and relationships on the street: How homeless men judge partner risk on Skid Row. AIDS and Behavior, 16, 774–784. 10.1007/s10461-011-9965-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2006). Constructing grounded theory Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Malone DK, & Clifasefi SL (2013). Housing retention in single-site Housing First for chronically homeless individuals with severe alcohol problems. American Journal of Public Health, 103, S269–S274. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree BF, & Miller WL (1999). Doing qualitative research Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Craig C, Eby D, & Whittington J (2011). Care coordination model: Better care at lower cost for people with multiple health and social needs Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell JW, & Plano Clark VL (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Doran KM, Misa EJ, & Shah NR (2013). Housing as health care—New York’s boundary-crossing experiment. New England Journal of Medicine, 369, 2374–2377. 10.1056/NEJMp1310121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S, LeFauve C, Kresky-Wolff M, & Rickards LD (2010). Services and supports for individuals with co-occurring disorders and long-term homelessness. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 37, 239–251. 10.1056/NEJMp1310121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer TP, Katz ML, Stefancic A, & Palinkas LA (2013). Variation in the implementation of California’s Full Service Partnerships for persons with serious mental illness. Health services research, 48(6pt2), 2245–2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer TP, Stefancic A, Henwood BF, & Ettner SL (2015). Fidelity to the Housing First model and variation in health service use within permanent supportive housing. Psychiatric Services, 66, 1283–1289. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer TP, Stefancic A, Sklar M, & Tsemberis S (2013). Development and validation of a Housing First fidelity survey. Psychiatric Services, 64, 911–914. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goering P, Veldhuizen S, Nelson GB, Stefancic A, Tsemberis S, Adair CE, … Streiner DL (2016). Further validation of the Pathways Housing First fidelity scale. Psychiatric Services, 67, 111–114. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henwood BF, Cabassa LJ, Craig CM, & Padgett DK (2013). Permanent supportive housing: Addressing homelessness and health disparities? American Journal of Public Health, 103, S188–S192. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henwood BF, Weinstein LC, & Tsemberis S (2011). Creating a medical home for homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 62, 561–562. 10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SW, O’Connell JJ, Lebow JM, Bierer MF, Orav EJ, & Brennen TA (2001). Health care utilization among homeless adults prior to death. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 12, 50–58. 10.1353/hpu.2010.0595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresky-Wolff M, Larson MJ, O’Brien RW, & McGraw SA (2010). Supportive housing approaches in the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness (CICH). Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 37, 213–225. 10.1007/s11414-009-9206-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, Atkins DC, Burlingham B, Lonczak HS, … Marlatt GA (2009). Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301, 1349–1357. 10.1001/jama.2009.414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone DK, Collins SE, & Clifasefi SL (2015). Single-site Housing First for chronically homeless people. Housing, Care and Support, 18, 62–66. 10.1108/HCS-05-2015-0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares AS, & Rosenheck RA (2011). A comparison of treatment outcomes among chronically homelessness adults receiving comprehensive housing and health care services versus usual local care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38, 459–475. 10.1007/s10488-011-0333-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matejkowski J, & Draine J (2009). Investigating the impact of Housing First on ACT fidelity. Community Mental Health Journal, 45, 6–11. 10.1007/s10597-008-9152-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw SA, Larson MJ, Foster SE, Kresky-Wolff M, Botelho EM, Elstad EA, … Tsemberis S (2010). Adopting best practices: Lessons learned in the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness (CICH). Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 37, 197–212. 10.1007/s11414-009-9173-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell JJ (2005). Raging against the night: Dying homeless and alone. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 16, 262–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK (2012). Qualitative and mixed methods in public health Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK, Henwood B, Abrams C, & Davis A (2008). Engagement and retention in services among formerly homeless adults with co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse: Voices from the margins. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 31, 226–233. 10.2975/31.3.2008.226.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK, Henwood BF, & Tsemberis SJ (2016). Housing First: Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives Oxford University Press, USA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK, Smith BT, Henwood BF, & Tiderington E (2012). Life course adversity in the lives of formerly homeless persons with serious mental illness: Context and meaning. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82, 421–430. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01159.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Chamberlain P, Hurlburt MS, & Landsverk J (2011). Mixed-methods designs in mental health services research: A review. Psychiatric Services, 62, 255–263. 10.1176/ps.62.3.pss6203_0255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway P, & Zipple AM (1990). The paradigm shift in residential services: From the linear continuum to supported housing approaches. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 13(4), 11. [Google Scholar]

- Somers JM, Moniruzzaman A, & Palepu A (2015). Changes in daily substance use among people experiencing homelessness and mental illness: 24‐month outcomes following randomization to Housing First or usual care. Addiction, 110(10), 1605–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, & Corbin J (1998). Basics of qualitative research Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Mares AS, & Rosenheck RA (2012). Does housing chronically homeless adults lead to social integration? Psychiatric Services, 63(5), 427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsemberis S, & Eisenberg RF (2000). Pathways to housing: Supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric services, 51(4), 487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, & Nakae M (2004). Housing First, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 651–656. 10.2105/AJPH.94.4.651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2015). The 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress Washington, DC: Office of Community Planning and Development. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness. (2010). Opening doors: Federal strategic plan to prevent and end homelessness Washington, DC: U. S. Interagency Council on Homelessness. [Google Scholar]

- Watson DP, Orwat J, Wagner DE, Shuman V, & Tolliver R (2013). The Housing First Model (HFM) fidelity index: Designing and testing a tool for measuring integrity of housing programs that serve active substance users. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 8, 16 10.1186/1747-597X-8-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein LC, Lanoue MD, Plumb JD, King H, Stein B, & Tsemberis S (2013). A primary care–public health partnership addressing homelessness, serious mental illness, and health disparities. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 26, 279–287. 10.3122/jabfm.2013.03.120239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen CK, Hudak PL, & Hwang SW (2007). Homeless people’s perceptions of welcomeness and unwelcomeness in healthcare encounters. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(7), 1011–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel SL (2014). HIV risk, drug use, social networks: Homeless persons transitioned to housing (Grant No. R01DA036245) Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel SL, Tucker JS, Elliott MN, & Hambarsoomians K (2007). Sexual risk among impoverished women: Understanding the role of housing status. AIDS and Behavior, 11(Suppl. 2), 9–20. 10.1007/s10461-006-9193-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]