Abstract

Background

Schwannomatosis is a genetic disorder that belongs to NF family. The mutation of SMARCB1 gene has been related to this entity and Coffin-Siris syndrome, as well. We reported a case of a female patient with SMARCB1 mutation who has developed a spontaneuous spleen rupture.

Case description

A 28 years old female patient with a story of a Sjogren syndrome, celiac disease and a surgically treated schwannoma, presented to our observation in July 2013 for a pain on the left elbow, where a tumefation was present. After neuroradiological evaluations, a surgical resection was performed and a schwannoma was diagnosed. Genetic exams revealed a puntiform SMARCB1 gene mutation. During 2015, she was subdued to the removal of an another schwannoma located into the cervical medullary canal. Few months later, she was operated in an another hospital for a spontaneous spleen rupture in a possible context of wandering spleen.

Conclusion

We think that the patient could suffer from a partially expressed Coffin-Siris syndrome. No cases of spontaneous rupture in a context of wandering spleen have been ever described as for as schwannomatosis or Coffin-Siris syndrome are concerned. More cases are necessary to establish a direct relationship.

Keywords: Schwannomatosis, Coffin-Siris, Spleen rupture, Sjogren, Wandering

Highlights

-

•

Schwannomatosis is a particular form of neurofibromatosis

-

•

Coffin-Siris and Schwannomatosis are related to mutations of SMARCB-1 gene

-

•

Wandering spleen has not described as related to Coffin-Siris syndrome

-

•

A particular puntiform mutation of SMARCB1 could be the cause

1. Introduction

When we speak about neurofibromatosis (NF), we mean a group of autosomal dominant hereditary diseases linked to the development of tumors of nervous and other organ systems. The three principal entities are NF1, NF2 and schwannomatosis. This last rare condition has been recognized recently and mutation of SMARCB1 gene has been found in 40–50% of familiar forms [1]; nevertheless, mutation of this gene has been found in Coffin-Siris syndrome (CSS), as well. Clinically, schwannomatosis is linked to the appearance of peripheral schwannomas, in absence of other organ involvements. We present the case of a patient with a schwannomatosis and Sjogren syndrome who has developed a spontaneous spleen rupture at the age of 31 years.

2. Case description

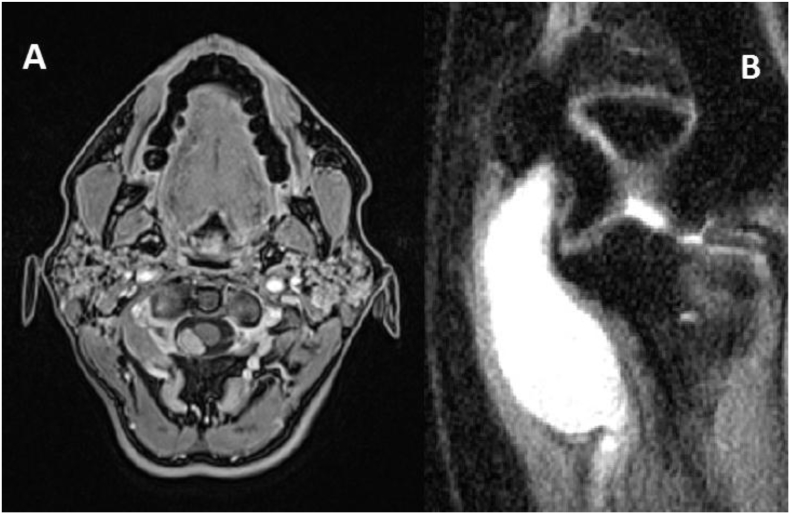

During July of 2013, a 28 years old female patient with an history of Sjogren syndrome, appendicectomy, celiac disease, multinodular thyroid goiter, ovarian cyst asportation, mild heart valvular insufficiency and left subfascial lumbar schwannoma treated in 2013, presented to our observation for the appearance of a tumefation into the left elbow. Moreover, he reported pain and left hand disestesiae (into the territory of ulnar nerve) and electric shock sense during palpation. Objective neurological examination revealed a subcutaneous left elbow tumefation in the region of ulnar nerve without any neurological deficit. An MRI with gadolinium was performed and showed a lesion with radiological attitudes of schwannoma (Fig. 1b). An electromiography showed evidence of medium grade entrapment of left ulnar nerve. We decided to remove the lesion from the left arm. During intervention we found a great neoplasia of 5 × 2.5 cm strictly adherent to the ulnar nerve. We performed an accurate dissection form the nerve, reaching a gross total resection. Pathology exam revealed an S100 positive lesion with micro- and macroscopic attitudes compatibles with a schwannoma. Postoperative course was regular and patient was discharged in a week without neurological deficits. We recommended genetic investigations and they revealed the mutation c.1120C > T (p.R374W) of gene SMARCB1 in chromosome 22; no puntiform mutations in NF1 and NF2 locus gene were found. Two years later, a follow-up MRI with gadolinium revealed an intradural extramedullary lesion at C1-C2 level (Fig. 1a). Clinically, she presented a normal objective neurological examination. So, we decided to operate her and a gross total resection was performed. Pathology exam revealed attitudes of schwannoma. No neurological deficits appeared after intervention. Postoperative course was regular and patient was discharged one week later. In March 2016 she was admitted to the Emergency of an another Hospital for the sudden appearance of an acute abdomen. No trauma history was reported. An urgent CT-scan revealed an hemoperitoneum with a spleen torsion likely. So, an urgent laparotomy was performed and a wandering, congested and ruptured spleen was found and removed. During postoperative period she was subdued to the vaccinations against S. Pneumoniae, N. Meningitidis and H. Influenzae and she was discharged two weeks later. Nowadays, she is in good conditions and no other new lesions suspected for schwannomas have been found.

Fig. 1.

MRI studies representing cervical (A) and elbow (B) schwannomas.

3. Discussion

Schwannomatosis is the most recent found form of neurofibromatosis, characterized by the development of schwannomas and chronic pain, with two distinct forms of pathology. Schwannomatosis 1 is related to mutation of SWI/SBF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily B, member 1, so-called SMARCB1, gene; on the contrary shwannomatosis 2 is linked to the germ-line inactivating mutation of leucine zipper-like transcriptional regulator 1, so-called LZTR1, gene [2]. SMARCB1 is considered an oncosuppressor gene because it permits the synthesis of a protein that regulates the transcription of p16INK4a and p21 and represses cyclin D13. In fact, its downregulation has been descripted as related to the formation of pediatric chordoma [3], while an epigenetic regulation by some miRNAs has been found in soft tissue sarcomas [4]. Moreover, some missense germ-line mutations of this gene have been related to CSS and to the possibility of malignant tumors [5].

We have described the case of a female patient with an history of multiple peripheral lesions. Two of them were operated and they revealed to be schwannomas. During follow-up radiological evaluation no sign of malignancy was found. So, it seems that her neoplastic history is limited to the presence of peripheral nervous system schwannoma. The particular attitude of her story is that in March 2016 she suffered from an acute abdomen due to an hemoperitoneum in absence of trauma history. During preoperative radiological evaluations, a spleen rupture in a context of hilum torsion was suspected and surgical intervention confirmed those suspects. Moreover, spleen was dislocated lower than its original position. This condition, that predisposes to organ infarction and rupture, is noted as wandering spleen. It is a rare condition, with an incidence of less than 0,2% among all cases of splenectomy [6], due to an absence or underdevelopment of spleen ligaments: gastrosplenic, colicosplenic, phrenocolic and phrenosplenic (splenorenal) ligament [7]. Classically, this condition is associated with multiparity and abdominal wall weakness [8] and can cause the torsion of spleen pedicle with a various degree. Possible surgical treatment consist of splenectomy and splenopexy [9].

Our patient did not have any pregnancy and she did not suffer from excessive thinness. Nevertheless, her history was remarkable for a Sjogren syndrome. It is a connective tissue disease, but in literature no case of wandering spleen related to this syndrome were reported. On the other hand, the fact that SMARCB1 gene mutations can be related to CSS cannot be forgotten. This syndrome is characterized by ectodermal anomaly that lead to hypo/aplasia of fifth phalanges and a certain degree of intellectual disability, as hypertrichosis/hirsutism and development delay. Moreover, organ anomalies, such as cardiac congenital defects and spinal anomalies can be found. Our patient did not have ectodermal anomalies described previously, but she brought us an echocardiography reporting a mild tricuspid, mitral and aortic valvular insufficiency, without clinical signs of congestive heart failure [10]. So, we don't have sufficient elements to formulate a diagnosis of Coffin-Siris syndrome but we can speculate that a less severe variant of this entity has occurred in our patient. Diets and colleagues, in their recent work, have described four cases of missense mutation in exon 2, resulting in the substitution of arginine with histidine. Clinically, this last finding has been seen related with a more severe form of syndrome, characterized by choroid plexus hyperplasia and hydrocephalus [11]. Our patient reported the mutation c.1120C > T (p.R374W) in exon 9, with arginine replaced by triptophane. Usually, in this exon, mutations related with a full-expressed Coffin-Siris syndrome were reported. Nevertheless, arginine in position 374 was replaced by glutamine [11]. To our knowledge, this type of mutation has never been described. For these reason, we can argue that patient could have a CSS without full phenotype expression, only with weakness of connective tissue. This could explain the presence of valvular insufficiency and wandering spleen, while the birth of peripheral schwannomas could be an acquired condition. In fact, some studied showed how a multiple hit mechanism is necessary to generate schwannomas [12]. A similar situation has been already described by Gossai et al. in 2015 [5] but, on the contrary, their patient had a frank Coffin-Siris syndrome with ectodermal anomalies and intellectual disability.

In conclusion, we have described the case of a female patient with schwannomatosis and a spontaneous spleen rupture due to a wandering spleen, with a mutation of SMARCB1 gene. To our knowledge, this is the first case described with a similar behavior and we think that it is related to a Coffin-Siris syndrome not fully expressed, probably caused by the particular puntiform mutation of the gene, but more cases are necessary to establish a tight relationship.

4. Conclusion

We described the case of a patient with a schwannomatosis, a spontaneous spleen rupture and a mutation of SMARCB1 gene. In consideration of her clinical history, we think that she could suffer from a partially expressed Coffin-Siris syndrome. No cases of spontaneous rupture in a context of wandering spleen have been ever described as for as schwannomatosis or Coffin-Siris syndrome are concerned. More cases are necessary to establish a direct relationship.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributor Information

G. Bellantoni, Email: g.bellantoni@gmail.com.

F. Guerrini, Email: frague21@gmail.com.

M. Del Maestro, Email: mattiadelmaestro@gmail.com.

R. Galzio, Email: r.galzio@smatteo.pv.it.

S. Luzzi, Email: s.luzzi@smatteo.pv.it.

References

- 1.Kresak J.L., Walsh M. Neurofibromatosis: a Review of NF1, NF2, and Schwannomatosis. J Pediatr Genet. 2016 Jun;5(2):98–104. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1579766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caltabiano R., Magro G., Polizzi A. A mosaic pattern of INI1/SMARCB1 protein expression distinguishes Schwannomatosis and NF2-associated peripheral schwannomas from solitary peripheral schwannomas and NF2-associated vestibular schwannomas. Child Nerv System. 2017 Jun;33(6):933–940. doi: 10.1007/s00381-017-3340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malgulwar P.B., Pathak P., Singh M. Downregulation of SMARCB1/INI1 expression in pediatric chordomas correlates with upregulation of miR-671-5p and miR-193a-5p expressions. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2017 Aug;20 doi: 10.1007/s10014-017-0295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sapi Z., Papp G., Szendroi M. Epigenetic regulation of SMARCB1 by miR-206, −381 and −671-5p is evident in a variety of SMARCB1 immunonegative soft tissue sarcomas, while miR-765 appears specific for epithelioid sarcoma. A miRNA study of 223 soft tissue sarcomas. Genes Chromosom. Cancer. 2016 Oct;55(10):786–802. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gossai N., Biegel J.A., Messiaen L. Report of a patient with a constitutional missense mutation in SMARCB1, Coffin-Siris phenotype, and schwannomatosis. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2015 Dec;167A(12):3186–3191. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tagliabue F., Chiarelli M., Confalonieri G. The Wandering Spleen. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2017 Sep;05 doi: 10.1007/s11605-017-3560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostermann P.A., Schreiber H.W., Lierse W. The ligament system of the spleen and its significance for surgical interventions. Langenbecks Arch. Chir. 1987;371(3):207–216. doi: 10.1007/BF01259432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chauhan N.S., Kumar S. Torsion of a Wandering Spleen Presenting as Acute Abdomen. Pol. J. Radiol. 2016;81:110–113. doi: 10.12659/PJR.895972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stringel G., Soucy P., Mercer S. Torsion of the wandering spleen: splenectomy or splenopexy. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1982 Aug;17(4):373–375. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(82)80492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vergano S.S., Deardorff M.A. Clinical features, diagnostic criteria, and management of Coffin-Siris syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. C: Semin. Med. Genet. 2014 Sep;166C(3):252–256. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diets I.J., Prescott T., Champaigne N.L. A recurrent de novo missense pathogenic variant in SMARCB1 causes severe intellectual disability and choroid plexus hyperplasia with resultant hydrocephalus. Genet Med. 2018 Jun;15 doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kehrer-Sawatzki H., Farschtschi S., Mautner V.F. The molecular pathogenesis of schwannomatosis, a paradigm for the co-involvement of multiple tumour suppressor genes in tumorigenesis. Hum. Genet. 2017 Feb;136(2):129–148. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1753-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]