Abstract

Introduction

Bosasso General Hospital is located in Puntland Somalia, an area affected by prolonged civil conflict, terrorism, clan fighting and piracy. International evidence highlights that staff skills and competence may have a significant impact on patient outcomes however there has been little research on emergency education in such an austere and volatile environment. The purpose of this study therefore was to identify current practices and gaps in delivering emergency medicine education in this resource-deprived environment.

Methods

A mixed methods approach was adopted to inform convergent parallel data collection techniques including questionnaire (n = 16), key informant (n = 5) and focus group interviews (n = 16). Data analysis, following data triangulation, produced descriptive quantitative statistics of themes such as emergency care, educational provision, enablers and barriers.

Results

The research showed that among health care staff at the hospital, 19% of the nurses felt that visiting nurses offer some knowledge on emergency care, while 38% of knowledge was gained from visiting doctors. Regarding knowledge of emergency medicine, 88.9% of the nurses felt that emergency medicine is basically first aid.

Discussion

Emergency care was perceived by the majority as essentially ‘first aid’. Many indicated that they received little or no regular or formal training on emergency care and related essential topics. In terms of challenges faced in delivering emergency care education demonstrated a common factor in the limited resources available which included lack of teaching materials, reading materials, online resources, health care professionals, equipment and mentors. Conclusions drawn suggest that the knowledge of emergency medicine by front line professionals is limited. Therefore, the development of field curricula, practical and theoretical training by visiting practitioners, provision of additional teaching aids, tools and equipment, integration of multiple disciplines in training and financial resource mobilisation would be beneficial in improving knowledge, attitudes and practices of emergency care.

Keywords: Health care professionals, Emergency care, Emergency medicine education, Visiting practitioners

African relevance

-

•

There is a need for identification of innovative ways of teaching emergency health care in resource-constrained environments.

-

•

There is a need to highlight the challenges faced when teaching emergency health care in Africa.

Introduction

The Federal Republic of Somalia is situated on the horn of the Eastern coast of Africa, with an estimated population of ten million. In 1960, the independent Somali Republic was established; however, in 1991, the government collapsed as the enduring civil war broke out. Somalia has since divided into three regional entities, including Somaliland, a self-declared Republic, Puntland, a Federal State of Somalia and South Central Somalia, the highly volatile remnant of the original Somali State [1]. Somalia is slowly on the path of reconstruction [2]. However, it remains a fragile state, with Islamic groups and rival clans in a highly fragile co-existence [1]. According to Somalia’s statistical health profile by the World Health Organisation (WHO), the life expectancy at birth is 53 years of age, with only 5% of the Somali population living over the age of 60. This can be inferred from the fact that the population is at risk as characterised by ongoing periods of civil unrest, terrorist attacks and conflict, which account for 4.1% of Somali deaths [3]. Furthermore, conflict also gives rise to physical and psychological injury to the population, and are thus contributing to the increasing burden of non-communicable diseases [4].

The health system in Somalia is organised and governed according to the states highlighted above (Somaliland, Puntland and South Central Somalia). The context for this research was the Puntland State of Somalia, a semi-volatile state with continued civil unrest, armed conflict and terrorism. Puntland is divided in to nine regions; the Bari region, which is the focus of the study, contains the only public health referral hospital, namely the Bossaso General Hospital. The Bossaso General Hospital is in the Central Business District (CBD) with two other private hospitals located less than a kilometre away. Bossaso General Hospital, funded by private donors and the local government, provides health services to a population of over one million people. As of 2014, Bossaso General Hospital had seven main departments, namely medical, surgical, paediatric, outpatient, operating theatres, maternity and an emergency centre (EC). Each department is staffed with health professionals of different cadres. The staff compliment of 76 comprises twelve doctors, 17 registered nurses (RN, Diploma), five administrative and 42 technical staff. The EC is staffed with two nurses, and whilst eleven nursing students are allocated to learn, they are encouraged to participate in clinical activities and rotate through the EC in this capacity, so supporting the team. Further, the facilities available in the ED are limited to basic First Aid equipment, vital sign measuring devices and improvised immobilisation devices.

Of 2336 inpatient admissions at Bossaso General Hospital in 2013, over 15% resulted from injuries. Injuries in this case are defined as physical trauma to the external human body such as burns, stab wounds, gunshot wounds, falls and road traffic accidents. This burden of disease is not unique to Somalia alone. Although epidemiological data is rarely collected or published [5], injuries are becoming an increasingly significant threat globally. However, the problem is growing considerably faster in the developing world [6], with 90% of injury related deaths occurring in low and middle-income countries [7]. Furthermore, injuries often involve a younger, predominantly male population, and can lead to long-term health issues increasing the strain on the already challenged health system.

In resource-limited settings, the lack of equipment and personnel are major obstacles to effective care and positive patient outcomes [8]. In turn, health care professionals have reduced skills and competence, influencing negatively, leading to suboptimal care and negative patient outcomes. Indeed, international morbidity and mortality rates are often influenced by the knowledge and skills of the health care professionals who provide emergency care [9].

The lack of timely assessment, monitoring and intervention concerning the physical needs of the critically ill and deteriorating patient is a causative factor of suboptimal care globally [9]. Therefore, health care professionals’ development is essential to support the acquisition and maintenance of competence, to ensure they are ‘equipped’ to handle presenting emergencies in the EC. It is essential that a robust education infrastructure be put in place to ensure the practice competence and continuing professional development.

The purpose of this study therefore was to identify current practices and gaps in delivering emergency medicine education in this resource-deprived environment. This in turn provided the opportunity to inform ongoing educational requirements, and strengthen the development of innovative methods of teaching and learning to support the delivery of effective care in this challenging setting, within the associated limited resources.

Methods

A ‘convergent parallel’ mixed-methods approach was used in this study, which included two distinct phases. The mixed-methods approach captured quantitative and qualitative data to arrive at a comprehensive analysis of the problem [10]. A non-probability sampling frame enabled purposive selection of participants. Inclusion criteria were health care professionals that had a minimum of three years’ post-registration experience involved in first emergency response. This was to ensure relevance of questions to gain informative results from the participants. Prior to data collection, a Participant Information Sheet was provided to explain the purpose of the study and what was asked of them. They were all informed of the purpose of the study, including the principal researcher’s position in the organisation. All participants were assured that confidentiality would be upheld, and that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any point without it influencing their role or status. It is worth noting that a Research and Ethics Committee does not exist at the Ministry of Health. However, written ethical approval was given through the Hospital Board of Directors, specifically the Hospital Director. The quantitative instrument was subjected to an initial pilot phase, adjusted by referring to the WHO Disease Patterns for the region, and consequently strengthened by collaborative expert input of senior Ministry of Health officials.

Phase one

This phase involved a closed answer questionnaire written in English and was distributed before the work shift began to 20 participants working at Bossaso General Hospital who are involved in first emergency response. The sample size of 20 was drawn from all staff who participate in emergency response procedures. This comprised four doctors, 14 nurses and two laboratory technicians. An 80% response rate was achieved as 16 participants completed phase one. The questionnaire was developed and designed by the Principal Researcher and guided by a group of Senior Officials from the Ministry of Health to better inform the process. The questionnaire was designed to elicit the self-informed knowledge, skills and attitudes from the participants. A local translator was trained on the objective of the research and use of the data collection tools, to aid the non-English speaking participants in completion of the questionnaire. The African Federation of Emergency Medicine (AFEM) 2013 Handbook of Acute and Emergency Care was the reference book used to measure their knowledge of emergency medicine.

Phase two

This phase involved key informant individual interviews and focus group discussions from various participants led by the principal researcher before the work shift began. Due to the experience and strategic knowledge, five administrative hospital management personnel were invited for the key informant individual interviews. Two focus group discussions totalling 16 participants, including two technical staff, and clinical staff comprising ten nurses and four doctors, were conducted by the principal researcher. The principal researcher then transcribed the interviews and focus group discussions verbatim for accuracy. The data was then manually coded and categorised into specific themes. This allowed further analysis across the qualitative datasets influenced by Braun and Clarke’s (2006) [11]. Method of Thematic Analysis, essentially a process for identifying significant patterns in the data. Both authors then immersed themselves in the data, developed individual codes and themes then came together to negotiate the final thematic presentation.

Since the study was a convergent parallel mixed method, the quantitative and qualitative data were analysed individually. The data was then converged and presented in the results section.

Results

The findings upon merging the qualitative and quantitative data are described below.

Emergency care context

The research showed that among health care staff at the hospital, 19% (n = 3) felt that ‘visiting nurses’ offer some knowledge on emergency care, while 38% (n = 6) of knowledge was gained from ‘visiting doctors’. Regarding knowledge of emergency medicine, 88.9% (n = 14) felt that emergency medicine is in essence first aid.

To explore the situation further, it was essential to gain an understanding of the participant’s contextual awareness of what constitutes ‘emergency care’. 81% (n = 13) stated that they were not familiar with the African Federation of Emergency Medicine (2013) [12] guidelines. In contrast, however, 75% (n = 12) of the staff said they regularly consulted emergency medicine protocols, mainly derived from a variety of available reference books which are often donated and therefore often outdated. One participant stated, “the library does not have enough books that we can read in emergency medicine topics, so we have to rely on handouts”.

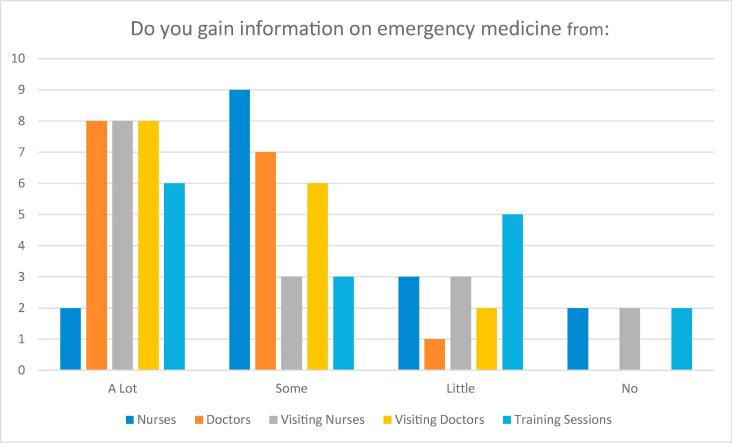

Furthermore, on exploration of the personnel responsible for emergency care delivery, most of the nurses indicated they gain ‘some’ knowledge from other nurses who they work with. A limited number of the nurses (6%) indicated that doctors were responsible for emergency care as it is their ‘specialty’ (Fig. 1). Yet only three (19%) nurses ‘agreed’ that poor resource settings like that of Bossaso General Hospital cannot practice emergency care. The majority concurred that it was a responsibility of all staff working in the hospital, especially in cases where there were mass casualty incidents (MCI). One participant stated, “There is no fixed rule that only nurses and doctors should participate – everyone tends to join in from all departments, even the radiology department”.

Fig. 1.

Emergency care perceptions.

Educational provision

Regarding the current provision and the actual requirements for emergency medicine education, most concurred and expressed the need for ongoing development for all disciplines to benefit the patient. Furthermore, participants described that education would also benefit community staff in their roles as first line responders. All participants included in the research had experience of emergency care. 69% (n = 11) however indicated that they have received little or no regular (monthly) training on emergency care and related topics.

Preliminary research among health care staff at the hospital (n = 16) (Fig. 2) showed that ‘visiting practitioners’ are a positive resource and provide knowledge and skills development on emergency care; 50% (n = 8) identified that ‘a lot’ of knowledge was gained from visiting practitioners and 37% (n = 6) answered that ‘some’ knowledge was gained. A ‘visiting practitioner’ in this context is any foreign medical practitioner nurse and/or doctor who is appointed for a continuous period of twelve months under a standard service contract approved by the government’s Ministry of Health (Somalia).

Fig. 2.

Access to emergency care education.

Due to the low resource setting, 63% (n = 16) of the staff reported that much of the educational provision that takes place at Bossaso General Hospital is primarily through practical sessions during On-the-Job-Training (OJT). According to one participant, “more detailed teaching of emergency medicine would involve visiting practitioners working in partnership with the Puntland Government”. In addition, “…the hospital has a library containing a variety of general medical textbooks, although many are not specific to emergency medicine”.

In terms of the guides used to inform staff on emergency medical care, there were multiple individuals who cited that they rely on doctors to teach them on a case-by-case basis. One participant said, “I use the help of the doctor who comes to assist in the casualty department”.

While two doctors and five nurses mentioned that practice is what guides them, the multidisciplinary team approach was also one of the ways mentioned to inform case management of patients presenting in the emergency room. However, a participant explained, “Apart from trauma cases – for medical cases, most of the time we have integrated other trainings but they are not specific to emergency medicine only”.

Barriers

In terms of barriers faced in delivering emergency care education, the participants consistently referred to the issue of limited resources. This included limited educational equipment, quality reading materials, online resources, available practitioners and experienced mentors. “There are not enough resources such as teaching material, practical sessions, books and online materials from the hospital,” one participant lamented.

Furthermore, no online resources were accessible in the hospital. “We do not have an online data base in the hospital where we can even access this kind of information even during the day when we are on break- if we had at least two or three online data bases, we can do a lot of self-learning,” according to a participant.

The participants also focused on the current nursing shortage in the hospital and predicted that this would only worsen the situation, especially if they had to be trained on emergency medical education outside the country. Regarding budgetary allocation of hospital funds to improving emergency medicine education, a key informant said, “there has never been a budget allocation for emergency medical education, because it has never been recognised as a specialty on its own”.

The medical doctor expressed that most of the financial donations as well as visiting practitioner’s fees are channelled to other departments and not necessarily to the emergency medical education budget.

Enablers

In terms of what can be done to improve the challenges faced in emergency medical education, a consistent message from all 16 participants was the increased need for more continuous medical educational (CME). A participant explained, “I believe books and reading material would be very important. When the staff read, at least they shall have some knowledge. This is because they do not have access to online information as they should.”

Others felt that OJT, additional resources such as online reading materials, textbooks, visiting practitioners, alternative sources of funding, and mentorship in emergency medicine would greatly improve the situation. A participant said, “how about educating the staff during work shift, so that they can engage in the practical training too? There should be a mentor or guide who comes from outside to teach them on emergency education.”

The perception of the contribution of senior management to improve the emergency medicine education received a mix response, with limited access to resources being the most common reason for the lack of training. One doctor mentioned, “we do undergo continuous medical education sessions from time to time that are facilitated by the senior consultant. The only problem is that we do not focus on emergency medicine education. The doctors are not that many and they are not trained in emergency medicine, so even the teaching and training is more of what we learn from each other and cases in the casualty department.”

When sustainable strategies were explored to ensure CME’s in emergency medicine education, 87% of the responses (n = 16) showed that visiting practitioners were key, due to a continuous presence, actual follow up, and range of material taught. In addition to this, the continuous provision of reading materials was also considered as key in sustainability. A participant explained, “for starters, there should be enough reading material available, whether it will be books or online information.”

Discussion

It is thus clear that very few staff were trained on emergency medicine. Furthermore, the frequency of and access to continuous medical education is limited. This is similar to other regions that have experienced conflict over many years. Ashton et al., on a study done on the impact of medical education in Iraq [13], showed that 50% of the students felt that the lack of training in medical education had been hampered by the ongoing conflict in the country. In terms of infrastructure, the emergency centre in the current study is comprised of three beds, basic surgical supplies and a measuring device for vital signs. In a similar study on the existing infrastructure post-conflict Rwanda [14], the converse was reported in the sense that infrastructure, personnel, equipment and supplies had improved due to support from the National Government. Although many staff do not seem to have a clear understanding of emergency care, reassuringly many show a keen interest in learning emergency medicine to benefit the patient.

The findings clearly indicated that the visiting practitioners were seen to offer a significant solution to delivering emergency medical education to both the medical and non-medical staff. This is partly due to the limited finances available to employ permanent emergency physicians. The hospital setting accommodates visiting practitioners, but mostly in other specialties such as medical, obstetrics, gynaecology and surgical departments. A cited example is a study done by Cunningham et al. on developing an emergency nursing short course in Tanzania, where partnerships with western institutions provide a great resource in emergency care [15]. It is apparent that the specialty of emergency medicine is not recognised, similar to conflict zones such as Iraq [13], hence senior management acknowledged this as a potential ‘quick fix’ solution that would benefit from visiting practitioners who are ideally emergency medicine specialists. In Ghana, a similar study on the development of an emergency nursing training curriculum, showed that external faculty (Western institution partnerships) proved to be an integral part in training of emergency medical education [7]. However, these partnerships have challenges based on the willingness of visiting practitioners to teach in highly volatile settings. In addition, recognition of emergency medicine as a specialty proved to be a foreign concept; in turn, respect and support was initially difficult [7].

The discussions overwhelmingly indicated that staff are not adequately trained, but did have a positive attitude to providing the best possible care within their ability for the emergency patient.

As much of the resources to employ emergency medical practitioners are limited, it was expressed that the provision of reading and learning materials should be made available in the form of textbooks, online training modules, and an in-hospital online information database, which can be used while staff are on duty. The guidelines provided in the AFEM handbook, which were donated to the staff in all departments, were very helpful. However, they were not sufficient for all the staff.

Other avenues to which emergency medicine education is being introduced is through practical and On-the-Job-Training (OJT). A similar study conducted in post conflict Nagorno-Karabagh looked at the impact of participation in the CME and obstacles to the application of obtained skills. All the respondents in the study indicated that the continuing medical education programme created important physician networks absent in this post-conflict zone, updated professional skills, and improved professional confidence among participants [16]. Rather than relying solely on a formal training program, the incorporation of teaching while on the job can be beneficial for both the staff and the patient. The staff learn best through practical teaching sessions, problem-based learning and continuous medical education [17]; however, it should be noted that this also requires the expertise and availability of personnel that can provide this knowledge, such as an emergency medicine physician and/or an emergency nurse specialist. As much as this would be the ideal in such a setting, the financial implication of employing such individuals proves to be one of the main challenges. This also proved to be a challenge in Ghana, on the debut of an emergency nursing training curriculum, where one of the major challenges faced was the recruitment, funding and support for external faculty [7]. Additionally, the perceived reluctance of foreign visiting practitioners to conduct teaching in Somalia is solely attributed to the volatile security situation. In this regard, other methods of learning could be explored, such as long distance online courses with opportunities to visit ideal EC facilities in order to put theory into practice. Shared learning can also be used as a method of improving the learning outcome by allowing for comparison with other EC staff in conflict stricken countries.

The major challenges to improving the deficit in emergency medicine education in such a context are access to contemporary quality evidence based information, as well as variability in the basic levels of education, cultural diversity, lack of funding, limited educational aids and equipment, time constraints, language barriers, unusual profile of the clients and the current security situation.

Whilst research within this setting is unique, the limitations include the relatively small sample size. The response rate may have been influenced by the data collection period being scheduled during the summer (June-August); the temperatures are high and thus most of the staff relocate to the cooler parts of the country and a skeleton staff base remains at the hospital.

In conclusion, this research suggests that the knowledge of emergency medicine by health care professionals in this context is limited and consequently present significant areas of concern that requires addressing as a matter of priority.

The recommendations refer to the development of field curricula, practical and theoretical advancements specific for the speciality of emergency care. Possible solutions include visiting practitioners, provision of emergency care teaching and learning tools and equipment. Integration of multi-disciplinary education and financial resource mobilisation could go some way to improving knowledge, attitudes and practices to emergency care. Additionally, an exploration of how information technology may influence future education provision is recommended, as there is a wealth of material available on the internet to enhance emergency care training. The question is whether the appropriate body for the quality of the training may add value to the learning process.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Bossaso General Hospital Administration for authorising access for the research, the staff of Bossaso General Hospital for participating in interviews and focus group discussions, and the Medical Emergency Response Team, United Nations Department of Safety and Security, Somalia for providing logistic support.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Dissemination of results

The results from this study were shared with staff members as well as at multiple conferences held in Africa and Europe respectively.

Authors’ contributions

IM conceived the original idea. IM designed the experiments. IM and MA collected the data. IM and JG carried out the analysis of the data. JG and IM drafted the manuscript. JG and MP revised it. IM, JG, MA and MP approved the final version that was submitted.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of African Federation for Emergency Medicine.

References

- 1.Quayad M.G. Health care services in transitional Somalia: challenges and recommendations. Int J Somal Stud. 2007;7:190–192. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farah A., Muchie M., Gundel J. Adonis & Abbey Publishers Ltd.; London: 2007. Somalia: Diaspora and State Reconstruction in the Horn of Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO Statistics profile 2002. [Cited 2014 April 8]. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/countries/som.pdf?ua=1.

- 4.World Health Organization. Non-communicable diseases and mental health: Non-communicable diseases country profiles 2011. [Cited 2014 March 5]. WHO Country Profile Brief. Available from: http://www.who.int/countries/som/en/.

- 5.Chandra A., Mullan P., Ho-Foster A. Epidemiology of patients presenting to the emergency care center of Princess Marina Hospital in Gaborone. Botswana. 2014;4:109–114. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seidenberg P., Cerwensky K., Brown R. Epidemiology of injuries, outcomes and hospital resource utilization at a tertiary teaching hospital in Lusaka, Zambia. Afr J Emerg Med. 2014;4(4):115–1112. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell S., Rockefeller O., Redman R. Development of an emergency nursing curriculum in Ghana. Int Emerg Nurs. 2014;22(2):202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osei K., Baker H., Freeman F. Essentials of emergency care: lessons from an inventory assessment of an emergency centre in Sub-Saharan Africa. Afr J Emerg Med. 2014;4(4):174–177. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donaldson R.I., Shanovich P., Shetty P. A survey of national physicians working in an active conflict zone: the challenges of emergency medical care in Iraq. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2012;27(2):153–161. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X12000519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creswell J.W. Sage; London: 2015. A concise introduction to mixed methods research. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. ISSN 1478-0887. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallis A.L., Reynolds T.A. Oxford University Press (Pty) Ltd; Cape Town, South Africa: 2013. AFEM Handbook of Acute and Emergency Care. African Federation of Emergency Medicine. 1st ed. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnett-Vanes A., Hassounah S., Shawki M. Impact of conflict on medical education: a cross-sectional survey of students and institutions in Iraq. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010460. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leana S.W., Douglas M.C. Existing infrastructure for the delivery of emergency care in post-conflict Rwanda: an initial descriptive study. Afr J Emerg Med. 2011;1(2):57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunninghama C., Brysiewiczb P., Sepekucf A., Whited L., Murraye B., Lobuef N. Developing an emergency nursing short course in Tanzania. Afr J Emerg Med. 2017;7(4):147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arin A.B., Hambardzum S., Kim H., Byron C. Adapting continuing medical education for post-conflict areas: assessment in Nagorno Karabagh – a qualitative study. Human Resour Health. 2014;12:39. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Azri H., Ratnapalan S. Problem-based learning in continuing medical education. Can Family Phys Publ. 2014;60(2):157–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]