Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to compare the short- and long-term outcomes after laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) between elderly and non-elderly patients with gastric cancer.

Methods: A retrospective analysis was performed using clinical and follow-up data from 168 patients treated with LTG for gastric cancer at our institution from January 2010 to December 2017. For this study, the short- and long-term outcomes (including tumor recurrence rate, disease-free survival rate, and overall survival rate) were compared between the elderly group (≥70 years) and non-elderly group (<70 years).

Results: The preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists score and Charlson Comorbidity Index were higher in the elderly group than in the non-elderly group, while there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of operation duration, intraoperative blood loss, and rate of conversion to laparotomy. The incidence of postoperative 30-day complications in the elderly group was higher than that in the non-elderly group due to a higher incidence of pulmonary infection, while the incidence of major complications was similar in both groups. The tumor recurrence rate was also similar in both groups. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of 5-year disease-free survival and 5-year overall survival rate.

Conclusions: LTG is safe and feasible for elderly patients with gastric cancer and is associated with relatively good long-term outcomes.

Keywords: laparoscopic total gastrectomy, gastric cancer, elderly, survival, minimally invasive surgery

Introduction

Gastric cancer is one of the most common gastrointestinal malignancies in East Asia 1, 2. As the aging population continues to increase, the proportion of elderly patients with gastric cancer has shown an associated rising trend 3, 4. Surgery is the only cure for patients with gastric cancer which can create a problem for elderly patients 5-8. Due to the impaired reserve function of important organs combined with medical comorbidities, many elderly patients have poor tolerance to surgery and higher risks of perioperative complications and death 5-8. In recent years, randomized control trials (RCT) have shown that laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG) has advantages for patients since it is generally less invasive, associated with a faster recovery, has comparable or fewer complications, and similar long-term outcomes to laparotomy 9-14. Therefore, its application in the treatment of gastric cancer has been increasingly widespread 15-32. As this approach has become more accepted, LG has also been gradually used in the treatment of elderly patients with gastric cancer 33-45. However, as reported in the literatures, laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (LDG) has been the main approach of LG used in the treatment of elderly patients with gastric cancer 33, 35-45. Currently, only two English studies have reported on the use of laparoscopic total gastrectomy LTG in the treatment of elderly patients with gastric cancer 34, 35. So far, there has been no comparison made regarding long-term outcomes of LTG between elderly and non-elderly patients with gastric cancer. This study aims to explore the clinical application value of LTG in the treatment of elderly patients with gastric cancer by comparing the short- and long-term outcomes of LTG between elderly and non-elderly patients.

Patients and methods

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki rules. This retrospective research was approved by the Ethics Committee of China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University. The need for informed consent from all patients was waived because this was retrospective study.

A total of 168 patients with gastric cancer underwent LTG at our institution from January 2010 to December 2017. Patients satisfying the following criteria were included in this study: (1) Definitive diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma was made by pathological examination based on preoperative endoscopic biopsy; (2) Clinical and follow-up information was complete; (3) The mode of operation was LTG, including intraoperative conversion to laparotomy; (4) Clinical stage I-III; (5) No neoadjuvant therapy was performed. Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) History of other malignant tumors, such as gastric lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma, stromal tumors and neuroendocrine tumors confirmed by preoperative or postoperative pathological examination; (2) Patients with esophageal-gastric junction adenocarcinoma that required thoracoabdominal surgery; (3) Patients that required combined organ resection due to local tumor invasion; (4) Patients with other concurrent malignant tumors. After screening, a total of 159 cases were included in this study. The short- and long-term outcomes (including tumor recurrence rate, disease-free survival and overall survival rate) were compared between the elderly group (≥70 years, 64 cases) and the non-elderly group (<70 years, 95 cases). Our institution began to perform laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer in March 2008. After performing this procedure for two years, the authors have mastered laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. The authors began performing laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) for gastric cancer in January 2010.

Electronic endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography, cranial, chest and abdominal CT scan, abdominal ultrasonography and other tests were performed prior to the surgery to determine the clinical stage and rule out metastasis 6. PET-CT and bone scans were performed when necessary. Laboratory tests, pulmonary function tests, electrocardiography, echocardiography and other tests were also performed prior to the surgery to evaluate whether the patients could tolerate it. Preoperative comorbidities were evaluated using the Charlson Comorbidity Scoring System 7. Details on LTG have been reported in previous literature 35. The severity of postoperative 30-day complications was graded using the Clavien-Dindo classification 45, which ranks the severity of postoperative complications into 5 grades. Mild complications are classified as grades 1 and 2, while severe complications are classified as grades 3, 4, and 5 45.

This study adopted a fast-track method for perioperative management. Solid food was prohibited for 6 hours and liquids were prohibited for 2 hours before surgery; no routine indwelling gastric tube was used before surgery, and any indwelling gastric tube already in place was removed one to two days after surgery; mechanical bowel preparation was not performed before surgery; prophylactic antibacterial agents were administered half an hour before surgery; general anesthesia or general anesthesia combined with epidural anesthesia was used; a urinary catheter was inserted after successful anesthesia and was removed one to two days after surgery; strict intraoperative thermal insulation was used; multimodal analgesia was given after surgery; a routine indwelling abdominal drainage tube was used and was removed after drainage ceased; careful rehydration was performed after surgery; oral intake of solid foods resumed as soon as possible after surgery; ambulation began on the first postoperative day 7.

Follow-up treatment was provided in different settings, which included outpatient visits, telephone calls, e-mails and home visits. The patients were followed-up once every 3 to 6 months within 2 years after the surgery, once every 6 months within 2 to 5 years after the surgery, and once a year over 5 years after the surgery 6. Patient assessments at follow up appointments included physical examinations, laboratory tests, and imaging studies. Follow-up appointments until January 1, 2018 were included in this study. The overall survival was assessed from the date of LTG until the last follow-up or death of any cause. The disease-free survival was calculated from the date of the LTG until the date of cancer recurrence or death from any cause 6.

Statistics

Variables were presented as mean and standard deviations for variables following normal distribution and were analyzed by t test. For variables following non-normal distribution, data were expressed as median and range and were compared by Wilcoxon test. Differences of semiquantitative results were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U-test. Differences of qualitative results were analyzed by chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Survival rates were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between two groups were analyzed with the log-rank test. Univariate analyses were performed to identify prognostic variables related to overall survival and disease-free survival. Univariate variables with probability values less than 0.10 were selected for inclusion in the multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model. Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) along with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. All statistical tests were two-sided, with the threshold of significance set at P<0.05 level.SPSS 14.0 for Microsoft ® Windows® version (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score and Charlson Comorbidity Index in the elderly group were higher than those in the non-elderly group. No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups of patients in terms of body mass index (BMI), sex, or TNM staging (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the two groups

| Non-elderly group (n=95) | Elderly group (n=64) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62 (51-69) | 73 (70-76) | 0.000 |

| Sex | 0.981 | ||

| Male | 64 | 43 | |

| Female | 31 | 21 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.001 | ||

| ≤ 2 | 86 | 45 | |

| > 2 | 9 | 19 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23 (19-27) | 22 (17-26) | 0.258 |

| Tumor location | 0.736 | ||

| Upper | 56 | 36 | |

| Middle | 39 | 28 | |

| Clinical TNM stage | 0.486 | ||

| IB | 23 | 11 | |

| IIA | 45 | 34 | |

| IIB | 27 | 19 | |

| ASA score | 0.020 | ||

| I | 66 | 38 | |

| II | 22 | 17 | |

| III | 7 | 9 | |

| Retrieved lymph nodes | 19 (16-25) | 17 (16-21) | 0.177 |

| Residual tumor (R0/R1/R2) | 95/0/0 | 64/0/0 | 1.000 |

| Histological subtype | 0.789 | ||

| Differentiated | 41 | 29 | |

| Undifferentiated | 54 | 35 | |

| Pathological TNM stage | |||

| IB | 17 | 8 | 0.818 |

| IIA | 31 | 25 | |

| IIB | 19 | 12 | |

| IIIA | 14 | 10 | |

| IIIB | 8 | 5 | |

| IIIC | 6 | 4 |

BMI: body mass index; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists

Comparisons of the operation duration, intraoperative blood loss, rate of conversion to laparotomy, postoperative exhaust time and time to first flatus after surgery did not reveal any statistically significant difference between the elderly group and the non-elderly group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Short-term outcomes of the two groups

| Non-elderly group (n=95) | Elderly group (n=64) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time (min) | 190 (160-260) | 210 (150-290) | 0.108 |

| Estimated blood loss (ml) | 200 (150-300) | 220 (180-390) | 0.150 |

| Conversion to open surgery | 5 | 4 | 1.000 |

| Time to first flatus (days) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-5) | 0.408 |

| Patients with postoperative 30-day complications | 10 | 15 | 0.028 |

| Pulmonary infection | 1 | 6 | 0.034 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 3 | 2 | 1.000 |

| Ileus Anastomotic stricture |

2 2 |

2 1 |

1.000 1.000 |

| Duodenal stump leakage | 1 | 2 | 0.728 |

| Abdominal infection | 2 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Liver dysfunction | 1 | 2 | 0.728 |

| Patients with postoperative 30-day major complications |

2 | 2 | 1.000 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days) | 7 (5-23) | 9 (7-28) | 0.239 |

| Readmission | 1 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Postoperative 30-day mortality | 0 | 0 | - |

The incidence of postoperative 30-day complications in the elderly group was higher than that in the non-elderly group because the incidence of pulmonary infection was higher in the in the elderly group than in the non-elderly group. However, the incidence of other complications, including the major complications was similar in both groups. None of the patients died during the surgery or within 30 days after the surgery (Table 2). Comparisons of the pathological data between the two groups did not reveal any statistically significant difference (Table 1).

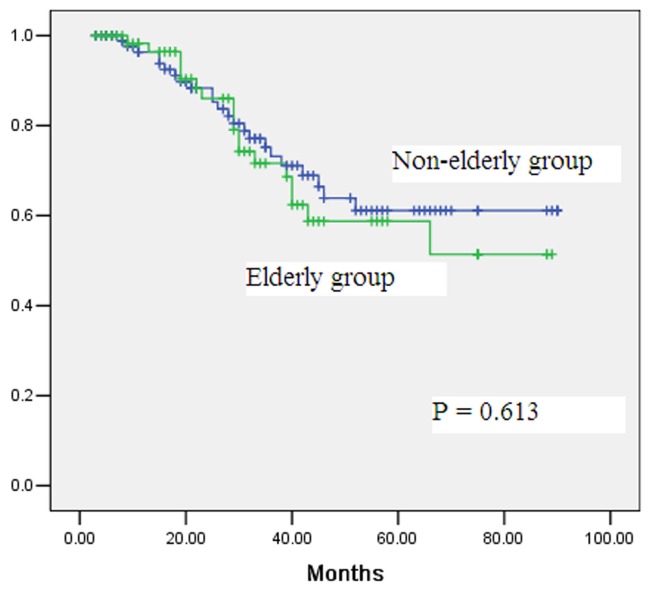

The median follow-up time for the elderly and non-elderly groups was 34 months and 37 months respectively, with no statistically significant difference. During the follow-up period, 18 and 23 deaths occurred in the elderly and non-elderly groups, respectively (Table 3). The 5-year overall survival rates in the elderly and non-elderly groups were 59% and 61%, respectively, with no statistically significant difference (Figure 1, P = 0.613). Multivariate analysis showed that the T staging, N staging and tumor differentiation status were independent predictors of overall survival rate (Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 3.

The follow-up data of the elderly and middle-aged group

| Non-elderly group (n=95) | Elderly group (n=64) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor recurrence n | 26 | 24 | 0.177 |

| Locoregional | 6 | 8 | |

| Distant | 17 | 14 | |

| Mixed | 3 | 2 | |

| Time to first recurrence (median, months) | 23 (8-50) | 21 (7-40) | 0.159 |

| Last follow up | |||

| Died of cancer recurrence | 21 | 16 | 0.672 |

| Died of non-oncological causes | 2 | 2 | 1.000 |

Figure 1.

Comparison of overall survival rates after laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer between elderly group (≥70 years) and non-elderly group (<70 years) (P=0.613).

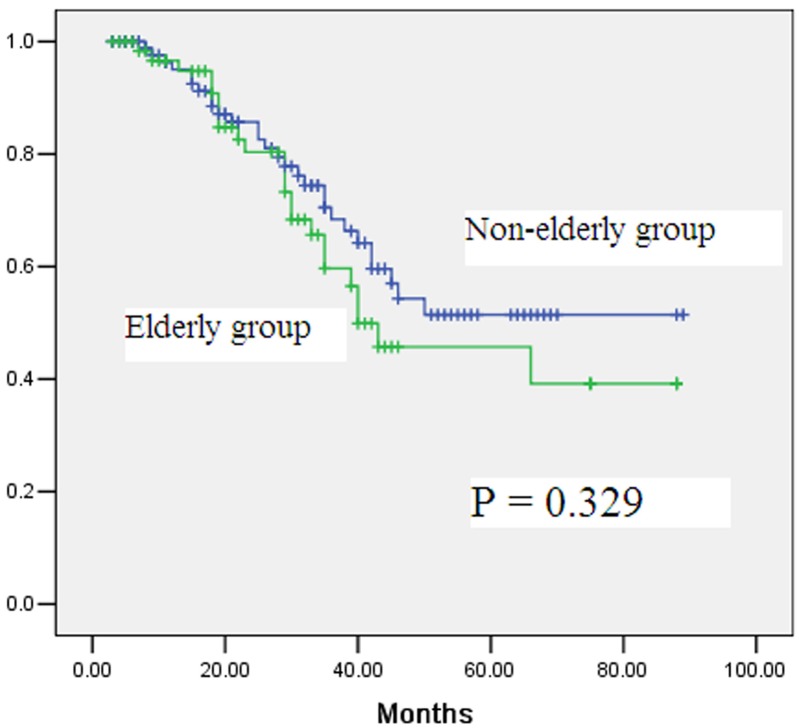

Table 4.

Univariate Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival

| Variable | Five-year overall survival | P value | Five-year disease-free survival | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.613 | 0.329 | ||

| <70 years | 61 | 51 | ||

| ≥70 years | 59 | 46 | ||

| Gender | 0.127 | 0.208 | ||

| Male | 64 | 54 | ||

| Female | 57 | 49 | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0.078 | 0.120 | ||

| ≤ 2 | 67 | 56 | ||

| > 2 | 51 | 47 | ||

| ASA score | 0.091 | 0.074 | ||

| I-II | 65 | 55 | ||

| III | 52 | 42 | ||

| Tumor differentiation | 0.017 | 0.038 | ||

| Differentiated | 71 | 61 | ||

| Undifferentiated | 48 | 46 | ||

| T stage | 0.010 | 0.018 | ||

| T1-T2 | 72 | 64 | ||

| T3-T4 | 43 | 40 | ||

| N stage | 0.023 | 0.020 | ||

| N0-N1 | 69 | 65 | ||

| N2-N3 | 46 | 44 | ||

| Postoperative complications | 0.247 | 0.187 | ||

| No | 63 | 58 | ||

| Yes | 56 | 51 | ||

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazards model for survival

| Variables | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index ≤ 2 versus > 2 | 1.389 (0.751-1.808) | 0.238 |

| ASA score I-II versus III | 1.254 (0.548-1.700) | 0.120 |

| T stage T1-T2 versus T3-T4 N stage N0-N1 versus N2-N3 |

1.980 (1.287-2.950) 2.456 (1.540-3.014) |

0.026 0.013 |

| Tumor differentiation Differentiated versus Undifferentiated | 1.544 (1.187-1.989) | 0.030 |

| Disease-free survival | ||

| ASA score I-II versus III | 1.387 (0.701-1.547) | 0.175 |

| T stage T1-T2 versus T3-T4 N stage N0-N1 versus N2-N3 |

1.701 (1.400-2.510) 2.017 (1.488-3.240) |

0.030 0.010 |

| Tumor differentiation Differentiated versus Undifferentiated | 1.300 (0.874-1.687) | 0.071 |

During the follow-up period, 24 and 26 patients, respectively, in the elderly and non-elderly groups experienced tumor recurrence (Table 3). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the rates and sites of tumor recurrence (Table 3). The 5-year disease-free survival rates in the elderly and non-elderly groups were 46% and 51%, respectively, with no significant difference (Figure 2, P = 0.329). Multivariate analysis showed that T staging and N staging were independent predictors of disease-free survival (Table 4 and Table 5).

Figure 2.

Comparison of disease-free survival rates after laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer between elderly group (≥70 years) and non-elderly group (<70 years) (P=0.329).

Discussion

Compared with laparotomy, LG has advantages as it is less invasive, it is associated with less intraoperative blood loss, less pain, rapid recovery after surgery and similar long-term outcomes 9-14. Therefore, it has been widely implemented in East Asia where the incidence of gastric cancer has been high 15-32. According to the range of surgeries, LG can be divided into LDG and LTG 7-9. Compared with LDG, LTG has characteristics such as a wide scope of lymph node dissection, a relatively complicated digestive tract reconstruction process, longer operation duration and higher rate of conversion to laparotomy 20-26. In recent years, LG has been widely used for elderly patients 33-45. However, most studies have reported on patients who received LDG which is less invasive, while only limited studies have reported on patients who received LTG which is more difficult to perform 34, 35. According to a search in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and other abstract databases by the author, currently only two English original articles have reported the use of LTG for the treatment of elderly patients with gastric cancer 34, 35. One study, reported by Korean surgeons Jung et al., compared the short-term outcomes of LTG between elderly patients (≥70 years) and non-elderly patients, but did not investigate the long-term outcomes 34. In another article by Chinese surgeons Lu et al., the study compared the short- and long-term outcomes between LTG and open TG in elderly patients with gastric cancer 35; however, the age of elderly patients included in that study was ≥65 years 35. To the best of the author's knowledge, this study is the first to report a comparison of short- and long-term outcomes of LTG between elderly patients (≥70 years) and non-elderly patients. The results of this study showed that the short- and long-term outcomes were similar in both groups except for the higher incidence of complications in the elderly group than in the non-elderly group. This indicates that LTG is safe and feasible for the treatment of elderly patients with gastric cancer, with similar long-term outcomes to that in non-elderly patients.

The incidence of postoperative 30-day complications in the elderly group was higher than that in the non-elderly group due to the higher incidence of pulmonary infections. However, studies have shown that advanced age along is a risk factor for pulmonary infection 6-9. In this study, the preoperative ASA score and Charlson Comorbidity Index were higher in elderly patients than in non-elderly patients, indicating decreased tolerance to surgery in elderly patients, which, combined with perioperative stress, led to the pulmonary infection. However, the lung infections in this study were all minor complications and recovered after intravenous administration of antibiotics. Comparison of the incidence of major complications and postoperative recovery between the two groups did not reveal any difference, suggesting that LTG is safe and feasible in elderly patients. If perioperative treatment is strengthened, good short-term efficacy can be achieved.

Conversion to laparotomy is unavoidable in LTG 9-19. The rate of conversion to laparotomy in LTG for gastric cancer reported in the literature was 3% to 15%, which varied according the patient's condition and surgical experience of the surgeons 15-37. In this study, the rates of conversion to laparotomy in the elderly group and non-elderly group were 6% and 5%, respectively, similar to previously reported results with larger sample sizes 15-37. In this study, most of the cases that converted to laparotomy were due to uncontrollable bleeding, followed by adhesion, while for only one case, it was due to a bulky tumor. So far, no English studies have reported on the rate of conversion to laparotomy in elderly patients undergoing LTG. This study for the first time showed that LTG had similar rate of conversion to laparotomy in elderly patients with gastric cancer to that in non-elderly patients.

In this study, long-term outcomes in both groups were similar, including tumor recurrence rate, overall survival and disease-free survival rate. According to previous reports, patients with gastric cancer who underwent LTG had a tumor recurrence rate of 10-30%, a 5-year overall survival rate of 50-70% and a 5-year disease-free survival rate of 41-60% 15-37. The results of this study were similar to those in previous reports 15-37. To the best of our knowledge, so far there is only one English article that reports the long-term outcomes of LTG-treated elderly patients with gastric cancer 35. In that article, the patients' 3-year overall survival rate was 55.8% 35. So far, there is no literature that reports on the 5-year overall survival rate and 5-year disease-free survival rate in LTG-treated elderly patients with gastric cancer. This study for the first time demonstrated that LTG-treated elderly patients with gastric cancer can achieve similar long-term outcomes to that in non-elderly patients.

Currently, there is no a clear definition of age for “elderly patients” in surgical oncology. In previous literature, the age limit of elderly patients with malignant tumors undergoing surgery was generally 65 to 75 years 33-44. In previous reports on LTG-treated elderly patients with gastric cancer, the age limit of the patients was 65 to 70 years 34, 35. Therefore, in this study, age ≥70 years was set as the cutting point for elderly patients with gastric cancer.

However, this study has several limitations. First, it was based on a single-center, retrospective analysis, not on a prospective randomized analysis. Second, the sample size was small, and the follow-up period was not very long. These limitations should be considered when interpreting our study results. In the future, a multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled study with a longer follow-up period is necessary to validate the safety of LTG for elderly patients with gastric cancer.

In conclusion, LTG is safe and effective in elderly patients with gastric cancer and can achieve satisfactory short-term and long-term outcomes. However, it should be noted that the surgical risk is generally higher in elderly patients than in non-elderly patients. Therefore, perioperative care and prevention and treatment of postoperative complications should be emphasized.

References

- 1.Sugano K. Screening of gastric cancer in Asia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;29(6):895–905. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sitarz R, Skierucha M, Mielko J, Offerhaus GJA, Maciejewski R, Polkowski WP. Gastric cancer: epidemiology, prevention, classification, and treatment. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:239–248. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S149619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan BA, Jang RW, Wong RK, Swallow CJ, Darling GE, Elimova E. Improving Outcomes in Resectable Gastric Cancer: A Review of Current and Future Strategies. Oncology (Williston Park) 2016;30(7):635–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim HS, Kim JH, Kim JW, Kim BC. Chemotherapy in Elderly Patients with Gastric Cancer. J Cancer. 2016;7(1):88–94. doi: 10.7150/jca.13248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coburn N, Cosby R, Klein L. et al. Staging and surgical approaches in gastric cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;63:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badgwell B. Multimodality Therapy of Localized Gastric Adenocarcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(10):1321–1327. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blakely AM, Miner TJ. Surgical considerations in the treatment of gastric cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42(2):337–357. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maduekwe UN, Yoon SS. An evidence-based review of the surgical treatment of gastric adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(5):730–741. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1477-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiki N, Katai H, Mizusawa J. et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with suprapancreatic nodal dissection for clinical stage I gastric cancer: a multicenter phase II trial (JCOG0703) Gastric Cancer. 2018;21(1):155–161. doi: 10.1007/s10120-016-0687-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu Y, Huang C, Sun Y. et al. Morbidity and Mortality of Laparoscopic Versus Open D2 Distal Gastrectomy for Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(12):1350–1357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.7215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi Y, Xu X, Zhao Y. et al. Short-term surgical outcomes of a randomized controlled trial comparing laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for advanced gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(5):2427–2433. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5942-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai J, Wei D, Gao CF, Zhang CS, Zhang H, Zhao T. A prospective randomized study comparing open versus laparoscopy-assisted D2 radical gastrectomy in advanced gastric cancer. Dig Surg. 2011;28(5-6):331–337. doi: 10.1159/000330782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inaki N, Etoh T, Ohyama T. et al. A Multi-institutional, Prospective, Phase II Feasibility Study of Laparoscopy-Assisted Distal Gastrectomy with D2 Lymph Node Dissection for Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer (JLSSG0901) World J Surg. 2015;39(11):2734–2741. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3160-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park YK, Yoon HM, Kim YW. et al. Laparoscopy-assisted versus Open D2 Distal Gastrectomy for Advanced Gastric Cancer: Results From a Randomized Phase II Multicenter Clinical Trial (COACT 1001) Ann Surg. 2018;267(4):638–645. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bo T, Peiwu Y, Feng Q. et al. Laparoscopy-assisted vs. open total gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: long-term outcomes and technical aspects of a case-control study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17(7):1202–1208. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee MS, Lee JH, Park DJ, Lee HJ, Kim HH, Yang HK. Comparison of short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy and open total gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(7):2598–2605. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2796-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin J, Huang C, Zheng C, Li P, Xie J, Wang J, Lu J. A matched cohort study of laparoscopy-assisted and open total gastrectomy for advanced proximal gastric cancer without serosa invasion. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127(3):403–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SR, Kim HO, Son BH, Shin JH, Yoo CH. Laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy versus open total gastrectomy for upper and middle gastric cancer in short-term and long-term outcomes. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24(3):277–282. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182901290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong O, Jung MR, Kim GY, Kim HS, Ryu SY, Park YK. Comparison of short-term surgical outcomes between laparoscopic and open total gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma: case-control study using propensity score matching method. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(2):184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen K, Pan Y, Zhai ST. et al. Totally laparoscopic versus open total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A case-matched study about short-term outcomes. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(38):e8061. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim EY, Choi HJ, Cho JB, Lee J. Totally Laparoscopic Total Gastrectomy Versus Laparoscopically Assisted Total Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2016;36(4):1999–2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen K, Pan Y, Cai JQ. et al. Totally laparoscopic versus laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy for upper and middle gastric cancer: a single-unit experience of 253 cases with meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:96. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0860-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang GT, Zhang XD, Xue HZ. Open Versus Hand-assisted Laparoscopic Total Gastric Resection With D2 Lymph Node Dissection for Adenocarcinoma: A Case-Control Study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2017;27(1):42–50. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagai E, Nakata K, Ohuchida K, Miyasaka Y, Shimizu S, Tanaka M. Laparoscopic total gastrectomy for remnant gastric cancer: feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(1):289–296. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3186-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emile SH. Evolution and clinical relevance of different staging systems for colorectal cancer. Minim Invasive Surg Oncol. 2017;1(2):43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shu B, Lei S, Li F, Hua S, Chen Y, Huo Z. Laparoscopic total gastrectomy compared with open resection for gastric carcinoma: a case-matched study with long-term follow-up. J BUON. 2016;21(1):101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu H, Li W, Chen G. et al. Outcome of laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. J BUON. 2016;21(3):603–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye M, Jin K, Xu G. et al. Short- and long-term outcomes after conversion of laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a single-center study. J BUON. 2017;22(1):126–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y, Jiang B, Liu T. Laparoscopic versus open total gastrectomy for advanced proximal gastric carcinoma: a matched pair analysis. J BUON. 2016;21(4):903–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emile SH. Advances in laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: fluorescence- guided surgery. Minim Invasive Surg Oncol. 2017;1(2):53–65. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ielpo B, Duran H, Diaz E. et al. Colorectal robotic surgery: overview and personal experience. Minim Invasive Surg Oncol. 2017;1(2):66–73. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emile SH. Laparoscopic intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer: technique, oncologic, and functional outcomes. Minim Invasive Surg Oncol. 2017;1(2):74–84. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu D, Li Y, Yang Z, Feng X, Lv Z, Cai G. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma in elderly patients: a pair-matched study. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9(2):3465–3472. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jung HS, Park YK, Ryu SY, Jeong O. Laparoscopic Total Gastrectomy in Elderly Patients (≥70 Years) with Gastric Carcinoma: A Retrospective Study. J Gastric Cancer. 2015;15(3):176–182. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2015.15.3.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu J, Huang CM, Zheng CH. et al. Short- and Long-Term Outcomes After Laparoscopic Versus Open Total Gastrectomy for Elderly Gastric Cancer Patients: a Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1949–1957. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2912-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohri Y, Yasuda H, Ohi M. et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic gastrectomy in elderly patients with gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(6):1627–1635. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3856-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tandon A, Rajendran I, Aziz M, Kolamunnage-Dona R, Nunes QM, Shrotri M. Laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy in the elderly: experience from a UK centre. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99(4):325–331. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida M, Koga S, Ishimaru K. et al. Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy is feasible also for elderly patients aged 80 years and over: effectiveness and long-term prognosis. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(11):4431–4437. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5493-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujisaki M, Shinohara T, Hanyu N. et al. Laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer in the elderly patients. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(4):1380–1387. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng L, Lu L, Jiang X, Jian W, Liu Z, Zhou D. Laparoscopy-assisted versus open distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer in elderly patients: a retrospective comparative study. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(9):4069–4077. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4722-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyasaka Y, Nabae T, Yanagi C. et al. Laparoscopy-Assisted Distal Gastrectomy for the Eldest Elderly Patients with Gastric Cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61(132):1133–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamada H, Kojima K, Inokuchi M, Kawano T, Sugihara K. Laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy in patients older than 80. J Surg Res. 2010;161(2):259–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumagai K, Hiki N, Nunobe S. et al. Potentially fatal complications for elderly patients after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17(3):548–555. doi: 10.1007/s10120-013-0292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park HA, Park SH, Cho SI. et al. Impact of age and comorbidity on the short-term surgical outcome after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma. Am Surg. 2013;79(1):40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao H, Xie P, Zhou K. et al. Clavien-Dindo classification and risk factors of gastrectomy-related complications: an analysis of 1049 patients. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(5):8262–8268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]