Abstract

The therapeutic effect of interferon (IFN) on chronic hepatitis C and its adverse effects have been well documented. Although the incidence of IFN-related cardiotoxicity is low, careful observation is necessary because of its possible fatal outcome. We describe a 45-year-old woman who suffered from sinus node dysfunction after the combination therapy of pegylated IFN-alpha and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. Despite the cessation of IFN therapy, sinus node dysfunction was not reversible, and led her to the implantation of permanent pacemaker. Physicians should therefore be aware of the possibility of sinus node dysfunction in patients receiving IFN therapy.

<Learning objective: Pegylated interferon-alpha has been widely used to treat hepatitis C virus infection, which is associated with a wide variety of adverse effects. There is a limited number of case reports regarding suspected interferon-induced cardiotoxicity, especially bradyarrhythmia. We report a case with chronic hepatitis C who developed sick sinus syndrome after interferon-alpha therapy.>

Keywords: Interferon, Sick sinus syndrome, Chronic hepatitis C, Side effect

Introduction

Interferon (IFN)-alpha has been widely used to treat hepatitis C virus infection and various malignant diseases. A wide variety of adverse effects of IFN has been reported previously [1]. There is a limited number of cases in the literature reporting bradyarrhythmia as an adverse drug reaction to IFN 2, 3. Here, we report a case of a 45-year-old woman with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1b treated with pegylated IFN-alpha (PEG-IFN) and ribavirin who developed sick sinus syndrome.

Case report

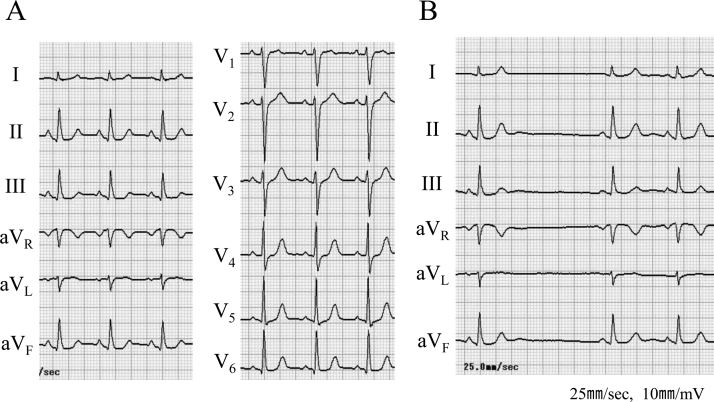

A previously healthy 45-year-old woman was referred to a hepatologist for the work up for liver injury incidentally spotted at an annual health check-up. On physical examination, her blood pressure was 140/80 mmHg, and pulse rate was 90 beats per minute (regular rhythm). There was no jugular venous dilatation, abnormal sounds on chest auscultation, or lower extremity edema. She had received a laboratory diagnosis of chronic hepatitis C, genotype 1b, and initiated combined therapy using PEG-IFN (80 μg/week) and ribavirin (600 mg/day) for 48 weeks. Electrocardiogram (ECG) before the therapy showed no rhythm abnormality (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Electrocardiogram before interferon therapy (A) and sino-atrial block found after 6 months (B).

Six months after the initiation of PEG-IFN therapy, she suffered from general malaise and, her ECG revealed sino-atrial (SA) block (Fig. 1B). Sinus cycle length was gradually decreased to 47/min during the therapy. She was diagnosed as having IFN-related hypothyroidism [thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) 41.13 μU/ml, free thyroxine (FT) 4 0.59 ng/dl, FT3 2.98 pg/ml], and treated with levothyroxine. Even after the normalization of TSH (1.85 μU/ml), her symptoms were not improved and were considered as a psychosomatic side effect, a common side effect of IFN therapy, and no further examination concerning bradycardia was performed. After the completion of scheduled PEG-IFN therapy, she consulted our division for a work up for presyncope and sinus bradycardia.

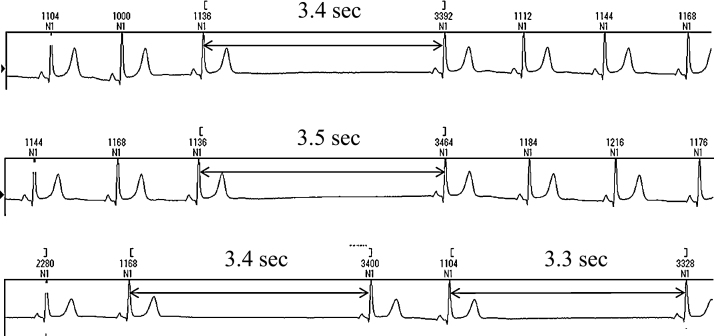

On physical examination, her consciousness was clear, blood pressure was 158/97 mmHg, and pulse rate was 57/min (regular rhythm). There was no jugular venous dilatation, abnormal sounds on chest auscultation, abnormal abdominal findings, or lower extremity edema. Examination of hematological and biochemical parameters revealed no abnormality except subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH 6.8 μU/ml, FT4 1.54 ng/dl, FT3 3.12 pg/ml). Echocardiography showed preserved cardiac function, and denied the existence of organic heart disease. We could confirm sinus bradycardia and frequent occurrences of SA block concomitant with presyncope on Holter ECG recordings (Fig. 2). The maximum, minimum, and mean heart rate was 98, 31, and 55/min, and total heart beats of the day was 74,327. RR intervals more than 3 s were observed 511 times a day, and reached 3.9 s in the maximum duration. There was no atrial fibrillation in Holter recordings repeated during follow-up.

Fig. 2.

Holter electrocardiographic recordings showing recurrent sino-atrial block accompanied with presyncope.

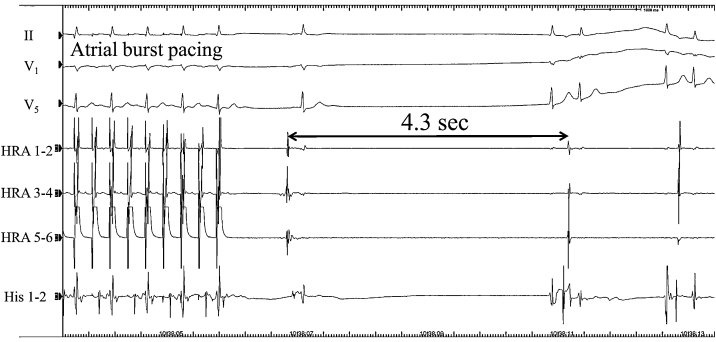

Electrophysiological study performed to evaluate the indication for pacemaker showed 4.3 s of the secondary pause following atrial overdrive pacing (Fig. 3). Atrio-ventricular conduction was preserved intact. From these findings, we made diagnosis of her illness as sick sinus syndrome, an adverse side effect of IFN.

Fig. 3.

Atrial overdrive pacing induced sinus pause and faintness. Even after the cessation of interferon therapy, sinus node dysfunction remained.

After the implantation of a permanent atrial pacemaker, her symptoms completely disappeared. Six months after the implantation, her heart rate was mostly dependent on the pacemaker even in day time. Her thyroid function was confirmed to be euthyroid (TSH 4.23 μU/ml, FT4 1.31 ng/dl, FT3 3.38 pg/ml). We temporarily decreased lower rate of the device to 45 bpm, and performed 24 h Holter ECG recording to re-evaluate her sinus node function. Almost a quarter (23%) of heart beats were produced by atrial pacing (45/min), that suggested sinus node dysfunction was irreversible.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report in which a previously healthy patient developed irreversible sinus node dysfunction after IFN therapy. In this case, we could not find any other cause of sinus node insufficiency except IFN therapy, and the implantation of permanent cardiac pacemaker was necessary.

IFN therapy has been performed widely to treat chronic hepatitis C virus infection, which is associated with several side effects, such as fever, feeling of malaise, headache, blood cell count decrease, and depression. A small number of cases of suspected IFN-induced cardiotoxicity have been reported in the literature. The most common manifestations of cardiotoxicity were tachyarrhythmias, such as paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation, which were mostly observed in patients with underlying heart disease [4]. Teragawa et al. reported that 10 of 295 patients with chronic hepatitis C experienced cardiovascular adverse effects of IFN [2]. One patient temporarily suffered from sinus bradycardia during IFN therapy, and improved after the cessation of IFN administration. Ribavirin, concomitantly used with IFN, reinforces the effects of IFN on sustained virologic responses. Torriani et al. reported in their randomized, placebo-controlled trial, that ribavirin did not affect the frequency of adverse events in IFN therapy [5].

Little is known about the mechanism of IFN-induced sinus node dysfunction, but Sasaki et al. reported that sensibility of sinus node to IFN varies according to the type of IFN or total dose [3]. The combination therapy with IFN-alpha and ribavirin reduces the liver expression of transforming growth factor beta-1 which promotes liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. On the other hand, the expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) is increased in sinusoidal cells [6]. With respect to the heart, MMP subfamilies degrade extracellular matrix proteins and increase cardiac fibrosis, which leads to myocardial remodeling 7, 8, 9. Previous studies showed that fibrosis in and around the sinus node provokes sinus node dysfunction 10, 11, 12. Cardiotoxicity of IFN is potentiated in pathophysiological conditions such as hypertensive heart disease [13]. High blood pressure observed in the present case might aggravate toxicity and make sinus node dysfunction irreversible. However, the exact pathogenic mechanisms of irreversible sinus node dysfunction remain to be elucidated.

The side effects of IFN show various manifestations, which can result in misdiagnosis of the cause of them. In the administration of IFN therapy, we should consider the possibility of sick sinus syndrome and check ECG regularly.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Russo M.W., Fried M.W. Side effects of therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1711–1719. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00394-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teragawa H., Hondo T., Amano H., Hino F., Ohbayashi M. Adverse effects of interferon on the cardiovascular system in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Jpn Heart J. 1996;37:905–915. doi: 10.1536/ihj.37.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sasaki M., Sata M., Suzuki H., Tanikawa K. A case of chronic hepatitis C with sinus bradycardia during IFN therapy. Kurume Med J. 1998;45:161–163. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.45.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonnenblick M., Rosin A. Cardiotoxicity of interferon. A review of 44 cases. Chest. 1991;99:557–561. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torriani F.J., Rodriguez-Torres M., Rockstroh J.K., Lissen E., Gonzalez-García J., Lazzarin A., Carosi G., Sasadeusz J., Katlama C., Montaner J., Sette H., Jr., Passe S., De Pamphilis J., Duff F., Schrenk U.M. Peginterferon Alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:438–450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guido M., De Franceschi L., Olivari N., Leandro G., Felder M., Corrocher R., Rugge M., Pasino M., Lanza C., Capelli P., Fattovich G. Effects of interferon plus ribavirin treatment on NF-kappaB, TGF-beta1, and metalloproteinase activity in chronic hepatitis C. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1047–1054. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zavadzkas J.A., Mukherjee R., Rivers W.T., Patel R.K., Meyer E.C., Black L.E., McKinney R.A., Oelsen J.M., Stroud R.E., Spinale F.G. Direct regulation of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase following myocardial infarction causes changes in survival, cardiac function, and remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1656–H1666. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00141.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y.Y., Feldman A.M., Sun Y., McTiernan C.F. Differential expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in the failing human heart. Circulation. 1998;98:1728–1734. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.17.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spinale F.G. Myocardial matrix remodeling and the matrix metalloproteinases: influence on cardiac form and function. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1285–1342. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thery C., Gosselin B., Lekieffre J., Warembourg H. Pathology of sinoatrial node. Correlations with electrocardiographic findings in 111 patients. Am Heart J. 1977;93:735–740. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(77)80070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bharati S., Nordenberg A., Bauernfiend R., Varghese J.P., Carvalho A.G., Rosen K., Lev M. The anatomic substrate for the sick sinus syndrome in adolescence. Am J Cardiol. 1980;46:163–172. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(80)90619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakabe M., Fujiki A., Nishida K., Sugao M., Nagasawa H., Tsuneda T., Mizumaki K., Inoue H. Enalapril preserves sinus node function in a canine atrial fibrillation model induced by rapid atrial pacing. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:1209–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.50100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Odashiro K., Hiramatsu S., Yanagi N., Arita T., Maruyama T., Kaji Y., Harada M. Arrhythmogenic and inotropic effects of interferon investigated in perfused and in vivo rat hearts: influences of cardiac hypertrophy and isoproterenol. Circ J. 2002;66:1161–1167. doi: 10.1253/circj.66.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]