Abstract

A 57-year-old male underwent mechanical mitral valve replacement for severe mitral regurgitation of a prolapsed myxomatous mitral valve. The patient's post-operative recovery period was uneventful until the eighth day when he decompensated into pulseless electrical activity arrest. A bedside transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a large, smooth-edged mass nearly obliterating the right atrial cavity. Color Doppler demonstrated flow within the right atrium around the mass. After computed tomography scan showed that an intrapericardial hematoma was extrinsically compressing the right atrium, the patient underwent emergent mediastinal exploration with evacuation of 700 ml of coagulated blood. The patient made a full recovery.

<Learning objective: Loculated intrapericardial hematoma is an infrequently encountered but serious complication of cardiac surgery that may lead to life-threatening cardiac tamponade. When clinically suspected, computed tomographic imaging or transesophageal echocardiography may be useful to confirm diagnosis. Hemodynamically significant intrapericardial hematoma should be treated by urgent surgical evacuation.>

Keywords: Tamponade, Post-operative hematoma, Intrapericardial hematoma, Cardiac surgery

Case report

A 57-year-old male presented to our institution with new-onset dyspnea and orthopnea. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed severe mitral regurgitation secondary to flail leaflet of a prolapsed myxomatous mitral valve (MV). After medical stabilization, he underwent successful MV replacement with a mechanical prosthesis. Closure was complicated by minor localized bleeding due to tissue friability, but hemostasis was achieved without significant difficulty. His initial post-operative course was uneventful and therapeutic anti-coagulation was achieved on coumadin with international normalized ratio staying in boundaries of therapeutic range.

On the 8th day of recovery, the patient began complaining of shortness of breath. His respiratory rate was 23 breaths/min with an SpO2 of 92% on room air. Telemetry revealed new onset atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response of 130 bpm. His blood pressure at that time was 110/68 mmHg when taken manually from the right arm in a seating position. Anterior–posterior chest X-ray was unremarkable. Eight hours later, the patient's condition deteriorated with his SpO2 lowering to 83% and his blood pressure then at 80/45 mmHg. He subsequently went into pulseless electrical activity arrest. Electromechanical association was restored following intubation, however his systolic blood pressure plummeted to 54 mmHg soon afterward necessitating initiation of ionotropic and vasopressor support to maintain adequate tissue perfusion. Physical examination revealed intact sternal incision site, clear lung fields, normal valvular click, and mild jugular venous distension. The remaining cardiac examination was unremarkable. Of note, his serum hemoglobin level was 8.6 g/dl compared to 12.1 g/dl prior to surgery.

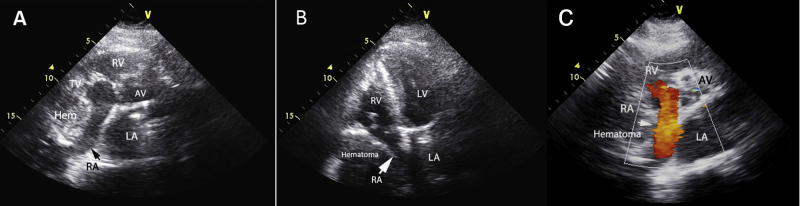

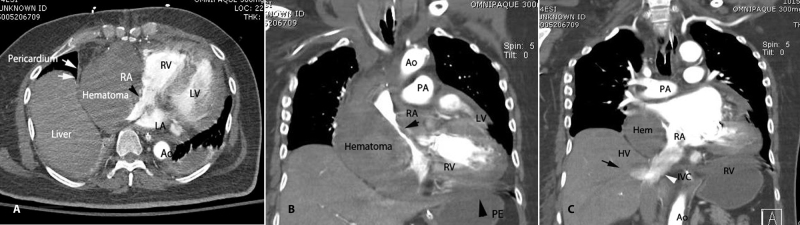

A repeat chest X-ray showed prominent widening of the right heart border and mediastinum not evident on previous chest X-ray. A bedside transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a large, smooth-edged mass nearly obliterating the right atrial cavity (Fig. 1A and B). Color Doppler demonstrated flow within the right atrium around the mass (Fig. 1C) and 2D imaging revealed motion independent of the walls of the heart suggestive of location outside of the right atrium. A computed tomography scan excluded intracavitary thrombus and confirmed that an intrapericardial hematoma (attenuation value of 60 Hounsfield Units) was extrinsically compressing the right atrium and leading to hemodynamic embarrassment from compromised ventricular filling (Fig. 2A–C). Additionally, there was unloculated pericardial hemorrhage that was missed on transthoracic echocardiography (Fig. 2A). The patient underwent emergent mediastinal exploration with removal of a total of 700 ml of coagulated blood from the pericardial space. Two days later a repeat echocardiogram demonstrated return of normal right atrial dimensions and ventricular filling. The patient made a full recovery.

Fig. 1.

Transthoracic echocardiogram. Parasternal short-axis view (A) and 4-chamber apical view. (B) Demonstrate presence of a large hematoma obliterating the RA cavity (white and black arrows). Addition of Color Doppler (C) shows flow in the RA (white arrow) around the hematoma suggesting extrinsic compression. RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; AV, aortic valve; TV, tricuspid valve; Hem, hematoma.

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography. Axial view (A) shows hematoma within the boundaries of the pericardium (white arrows). The hematoma is large enough to distort the RA cavity (black arrowhead). Coronal view (B) demonstrates unloculated pericardial effusion (black arrowhead) not detected initially by transthoracic echocardiography. In this coronal view (C) reflux of contrast down the inferior vena cava (white arrowhead) to level of the hepatic veins (black arrow) is seen, suggestive of severely elevated RA filling pressure. RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; Ao, aorta; PE, pericardial effusion; PA, pulmonary artery; IVC, inferior vena cava; HV, hepatic vein.

Discussion

Post-operative pericardial effusion and mediastinal bleeding are common sequelae of open heart surgery. In a study of 122 patients, 84% went on to develop post-operative effusions; however only one case progressed to hemodynamically significant effusion requiring intervention [1]. Excessive mediastinal bleeding warranting exploration has not been shown to be related to pre-operative coagulation study levels, use of aspirin or warfarin, total bypass time, or number of vessels bypassed [2]. While infrequent, loculated hematoma may form in the pericardial space and lead to regionalized, yet life-threatening tamponade from extrinsic compression of one or more cardiac chambers.

Post-operative hemorrhage can be missed if outside the planes visualized during routine transthoracic echocardiography or if echodense, coagulated blood in the pericardial space is not distinguishable from surrounding tissue [3]. When clinical suspicion remains high, computed tomography is useful to confirm presence of hematoma and to identify location and size [4], [5]. We postulate that continued localized bleeding after surgery due to tissue friability of the myocardium was the cause of intrapericardial hematoma accumulation in this case. Bleeding in this space likely became hemodynamically apparent once the patient went into atrial fibrillation and lost a significant portion of ventricular filling by the atria. Rapid recognition of expanding hematoma on surface echocardiography and confirmation of extracardiac location resulted in timely, life-saving intervention.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Weitzman L.B., Tinker W.P., Kronzon I., Cohen M.L., Glassman E., Spencer F.C. The incidence and natural history of pericardial effusion after cardiac surgery—an echocardiographic study. Circulation. 1984;69:506–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.69.3.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michelson E.L., Torosian M., Morganroth J., MacVaugh H. Early recognition of surgically correctable causes of excessive mediastinal bleeding after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Am J Surg. 1980;139:313–317. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(80)90284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerber R.E., Payvandi M.N. Echocardiography in acute hemopericardium: production of false negative echocardiograms by pericardial clots. Circulation. 1977;55–56(Suppl. 111):11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fyke E., III, Tancredi R.G., Shub C., Juslrud P.R., Sheedy P.F., II Detection of intrapericardial hematoma after open heart surgery: the roles of echocardiography and computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:1496–1499. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kochar G.S., Jacobs L.E., Kotler M.N. Right atrial compression in postoperative cardiac patients: detection by transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;16:511–516. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90613-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]