To the Editor: Clinical symptom spectrum of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is consisted of chronic intravascular hemolysis, hemoglobinuria, relative bone marrow failure, and the rarity of thrombosis.[1] The neurological complications generated by PNH were almost exclusively a result of cerebral venous thrombosis.[1,2,3] However, moyamoya syndrome (MMS) secondary to PNH (PNH-MMS) is rarely described in the literature.[2,3,4,5] We report herein a case of PNH-MMS to raise the awareness of this disease in PNH patients presenting with acute neurological deficits.

In May 2000, a 21-year-old male patient with no past medical or family history first visited our hospital for 1-week weakness and lumbago. The hemograms disclosed the picture of pancytopenia (platelet counts: 8 × 109/L, hemoglobin: 50 g/dl, and leukocyte counts: 2 × 109/L). Bone marrow examination (BME) showed hypocellularity in the myeloid and megakaryocytic series. Cytogenetic studies of bone marrow cells revealed normal male karyotype (46XY), and sugar-water test was negative. Therefore, aplastic anemia (AA) was diagnosed, and prednisolone and androgen were administrated to him. After 5-year medical treatment, surprisingly, his hemograms had recovered to normal level; meanwhile, drugs were withdrawn from him without any complications.

In July 2011, he visited our clinic for repeated hemoglobinuria. Hemolytic pattern of peripheral blood smear was noted with hemoglobin: 36 g/L, red cell counts: 2.0 × 1012/L, platelet counts: 112 × 109/L, and leukocyte counts: 8.95 × 109/L. BME demonstrated hypercellularity in the erythroid series. Rest tests were negative. However, Ham and sugar-water tests showed strong positive results. PNH was verified by flow cytometric measurement on erythrocytes and granulocytes. This patient received prednisolone and washed red blood cell transfusion (WRBCT). Since then, occasional blood transfusions were needed for severe anemia.

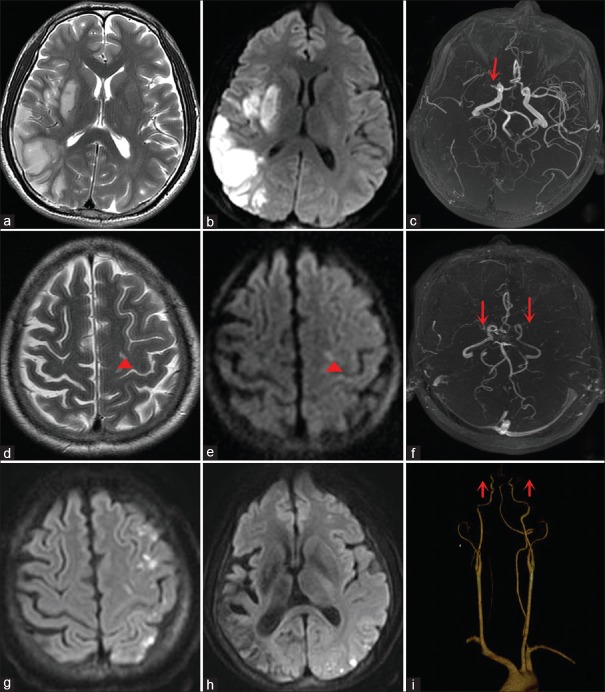

Unfortunately, 1 year later, he was brought to our unit with chief complaint of the left limb weakness for 2 days. The thorough neurological examination was remarkable including the finding of dysarthria, moderate left-side hemiparesis, and right facial palsy of central type. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 7. Laboratory examination showed typical hemolytic anemia (hemoglobin: 50 g/L, red cell counts: 2.5 × 1012/L, platelet counts: 110 × 109/L, and leukocyte counts: 9.0 × 109/L). Rest tests were negative including repetitive electrocardiograms, coagulation function, D-dimer testing, and autoimmune antibody screening. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggested acute cerebral infarction [Figure 1a and 1b]. Brain magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) revealed high-grade stenosis or obstruction in the right middle cerebral artery [Figure 1c]. There were no vascular risk factors except PNH found in this patient including hypercoagulable states, oral contraceptive use, paradoxical emboli related to an intracardiac shunt (patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect), atherosclerotic risk factors, or cardiac arrhythmias. After admission, aspirin, prednisolone, and WRBCT were administrated. On day 7, the patient was discharged for some improvements in neurological deficits. In the following 12 months of telephone follow-up, this patient did not go through new neurological deficits, but he refused cerebrovascular reexamination.

Figure 1.

(a and b) Brain MRI scanned in 2011 showed acute infarction in the right temporal lobe and basal ganglion. (c) MRA showed high-grade stenosis in the right middle cerebral artery (red arrow). (d and e) Brain MRI scanned in 2016 showed punctuate infarction in the left frontal lobe (red short arrowheads). (f) MRA showed severe stenosis in the terminal portion of bilateral internal carotid arteries (red arrows). (g and h) Repeated DWI showed multiple punctate hyperintensity in the left hemisphere. (i) CTA showed severe stenosis in terminal portion of bilateral internal carotid arteries (red arrows). MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; MRA: Magnetic resonance angiography; DWI: Diffusion-weighted imaging; CTA: Computed tomography angiography.

In 2016, he was referred to our clinic again due to 4-day dizziness and inarticulacy. NIHSS score was 3. Brain MRI disclosed subacute lacunar infarction in the left frontal lobe [Figure 1d and 1e]. Brain MRA revealed severe stenosis in the terminal portion of bilateral internal carotid arteries, suggesting moyamoya changes [Figure 1f]. Laboratory examination showed typical hemolytic anemia (hemoglobin: 73 g/L and red cell counts: 2.10 × 1012/L). Normal findings were found including repetitive electrocardiograms, coagulation function, D-dimer testing, and autoimmune antibody screening. On following day, the patient developed progressive inarticulacy accompanied with twice hemoglobinuria. NIHSS score was 5. An urgent repeated diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) suggested multiple acute infarcts in the left hemisphere [Figure 1g and 1h]. Meanwhile, computed tomography angiography demonstrated imaging characteristics of moyamoya disease [Figure 1i]. Moreover, the diagnosis of PNH-MMS was established. Both digital subtraction angiography and bypass surgery were suggested and refused. After a course of conservative treatments including aspirin, prednisolone, and WRBCT, his symptoms had some improvements. However, l year later, we knew from a telephone follow-up that he had lost the ability to work for deteriorating weakness of the right limbs.

MMS is a chronic occlusive cerebrovascular disease characterized by steno-occlusive changes around the terminal portions of bilateral or unilateral internal carotid artery and proximal arteries accompanied by the development of fragile collateral network usually with various underlying diseases (hematopathy, Down's syndrome, and autoimmune disorder).[6] However, to the best of our knowledge, PNH-MMS was rare, with only four published cases reported in the literature to date.[2,3,4,5]

The pathogenesis of PNH-MMS is multifactorial. It was suggested that chronic arterial thrombosis secondary to autoimmunity may be the main cause of MMS formation.[2,3] In PNH patient, deficiency of two important complement regulatory proteins on cell surfaces, CD55 and CD59, makes blood cells more sensitive and vulnerable to the action of complement response. Subsequently, increased free hemoglobin, activation of platelet, endothelial dysfunction, and inflammatory reaction can cause chronic hemodynamic changes and further hypoxia, vascular ischemia, or thrombosis, which is closely related to the formation of MMS.[1,7,8] Thus, we propose that PNH-MMS may be associated with a series of secondary hemodynamic changes mediated by autoimmunity. Moreover, a 9-year-old PNH-MMS boy had obvious improvement both in symptoms and follow-up brain angiography after being treated by eculizumab alone, which also can support such hypothesis.[4]

In the early stage of disease, our PNH-MMS patient was initially diagnosed as AA, which has been similarly reported in previous literature.[2,5] PNH associated with AA could be an immune-mediated disease, and this immune process could provide the selection pressure that favors the outgrowth of PNH clone.[7] Moreover, when PNH was associated with AA, a high probability of response to immunosuppressive therapy and a favorable prognosis were observed in these patients, suggesting that they would be in a subclinical PNH state.[7,8] This may explain why our patient was initially diagnosed as AA and had improvement in the early stage of the disease.

In conclusion, MMS should be also considered apart from cerebral venous thrombosis in PNH patients presenting with acute neurological deficit. In this situation, intracranial vessels should be regularly assessed for PNH patients.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that his name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Qiang Shi

REFERENCES

- 1.Griffin M, Munir T. Management of thrombosis in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: A clinician's guide. Ther Adv Hematol. 2017;8:119–26. doi: 10.1177/2040620716681748. doi: 10.1177/2040620716681748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin HC, Chen RL, Wang PJ. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria presenting as moyamoya syndrome. Brain Dev. 1996;18:157–9. doi: 10.1016/0387-7604(95)00145-x. doi: 10.1016/0387-7604(95)00145-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mugikura S, Higano S, Fujimura M, Shimizu H, Takahashi S. Unilateral moyamoya syndrome involving the ipsilateral anterior and posterior circulation associated with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Jpn J Radiol. 2010;28:243–6. doi: 10.1007/s11604-009-0412-6. doi: 10.1007/s11604-009-0412-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yen TA, Lu MY, Kuo MF, Huang CC, Chen JS, Yang YL. Eculizumab treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria presenting as moyamoya syndrome in a 9-year-old male. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:203–4. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24070. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang HZ, Pan LM, Wu JS. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria with moyamoya disease: A case report (in Chinese) Chin J Hematol. 2001;22:557. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott RM, Smith ER. Moyamoya disease and moyamoya syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devalet B, Mullier F, Chatelain B, Dogné JM, Chatelain C. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: A review. Eur J Haematol. 2015;95:190–8. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12543. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weitz IC. Thrombosis in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria-insights into the role of complement in thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2010;125(Suppl 2):S106–7. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(10)70026-8. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(10)70026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]