Abstract

Background:

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease under genetic control. Growing evidences support the genetic predisposition of HLA-DRB1 gene polymorphisms to SLE, yet the results are not often reproducible. The purpose of this study was to assess the association of two polymorphisms of HLA-DRB1 gene (HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15) with the risk of SLE via a comprehensive meta-analysis.

Methods:

This study complied with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement. Case-control studies on HLA-DRB1 and SLE were searched from PubMed, Elsevier Science, Springer Link, Medline, and Cochrane Library database as of June 2018. Analysis was based on the random-effects model using STATA software version 14.0.

Results:

A total of 23 studies were retained for analysis, including 5261 cases and 9838 controls. Overall analysis revealed that HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms were associated with the significant risk of SLE (odds ratio [OR]: 1.60, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.316–1.934, P = 0.129 and OR: 1.68, 95% CI: 1.334–2.112, P = 0.001, respectively). Subgroup analyses demonstrated that for both HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms, ethnicity was a possible source of heterogeneity. Specifically, HLA-DR3 polymorphism was not associated with SLE in White populations (OR: 1.60, 95% CI: 1.320–1.960, P = 0.522) and HLA-DR15 polymorphism in East Asian populations (OR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.248–2.173, P = 0.001). In addition, source of control was another possible source for both HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms, with observable significance for HLA-DR3 in only population-based studies (OR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.370–1.990, P = 0.244) and for HLA-DR15 in both population-based and hospital-based studies (OR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.078–1.760, P = 0.123 and OR: 2.08, 95% CI: 1.738–2.490, P = 0.881, respectively).

Conclusions:

HLA-DRB1 gene may be a SLE-susceptibility gene, and it shows evident ethnic heterogeneity. Further prospective validations across multiple ethnical groups are warranted.

Keywords: HLA-DR15, HLA-DR3, HLA-DRB1, Meta-Analysis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

摘要

背景:

系统性红斑狼疮是一种遗传性自身免疫疾病,研究发现其发病与HLA-DRB1基因遗传多态性相关。本研究旨在通过荟萃分析评估HLA-DRB1基因的两个基因多态性(HLA-DR3和HLA-DR15)与SLE风险之间的关系。

方法:

本研究符合PRISMA声明。从PubMed,Elsevier Science,Springer Link,Medline和Cochrane图书馆数据库中搜索了截至2018年6月对HLA-DRB1和SLE的病例对照研究。通过STATA14.0软件建立随机效应模型进行分析。

结果:

本文共纳入23篇文献进行分析,包括5261例和9838例对照。总体分析显示,HLA-DR3和HLA-DR15多态性与SLE的显着风险相关(优势比[OR]:1.595,95%置信区间(CI):1.316-1.934,P <0.01和OR:1.678,95 %CI:1.334-2.112,分别为P <0.001)。亚组分析表明, HLA-DR3和HLA-DR15多态性,种族是异质性的可能来源。具体而言,HLA-DR3多态性与白人群体中的SLE显著相关(OR:1.60,95%CI:1.29-1.99,P <0.01),以及东亚人群中的HLA-DR15多态性(OR:1.646,95%CI: 1.248-2.173,P <0.01)。此外,患者来源是HLA-DR3和HLA-DR15异质性的另一个可能来源,社区来源的人群分析研究中可发现HLA-DR3异质性有统计学意义(OR:1.65,95%CI:1.37-1.99,P <0.01)。在HLA-DR15社区/医院人群来源分析中,同样具有统计学意义(OR:1.378,95%CI:1.078-1.760,P <0.01和OR:2.08,95%CI:1.738-2.49,P <0.01)。

结论:

HLA-DRB1基因可能是SLE易感基因,具有种族异质性。

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic multisystem autoimmune disease predominantly affecting women, and its clinical features always include hematological abnormalities, skin and joint diseases, renal disease, and neuropsychiatric complications.[1,2] SLE is characterized by the development of dysregulated autoreactive B-cell-derived autoantibodies directed against nuclear and cellular components and the activation of complex inflammatory cascades, thereby resulting in multisystem organ damage.[1,2]

It is well established that the pathogenesis of SLE is multifactorial, to which genetic, endocrine immunologic, and environmental factors contribute interactively.[1,2] A better understanding of the genetic basis of SLE has recently emerged from studies of families, candidate genes, and genome-wide scanning. There is evidence that monozygotic twins were observed to have a much higher rate of disease concordance than dizygotic twins, indicating a strong genetic component in SLE.[3] In addition, more than 52 candidate loci in predisposition to SLE have been identified by a large panel of genome-wide association studies across various ethnical groups in the past two decades.[4,5,6,7,8,9] It is of interest to notice that a majority of SLE candidate genes and loci are functionally relevant to immune system, in particular the genes located in human lymphocyte antigen (HLA) regions.[10] The HLA gene is mapped on chromosome 6p21.3, and it encodes the major histocompatibility complex proteins in humans,[11] which has a pivotal role in the regulation of immune system. The genomic sequences of HLA gene are highly polymorphic, and growing evidence indicate that its different alleles are able to modulate the adaptive immune system.[11] It is widely recognized that dysregulation of antigen presentation by HLA proteins to T-cells leads to abnormal T-cell-mediated adaptive response, which may explain why different HLA gene alleles contribute to the pathogenic development of SLE.[1,2] Several HLA haplotypes were strongly linked to the pathogenic development of SLE. For example, three HLA haplotypes were significantly associated with SLE susceptibility in Caucasians.[12] In addition, Natalia et al.[13] conducted a meta-analysis, showing that HLA-DR2 and HLA-DR3 genes were associations with the risk of SLE in Latin Americans.

Although the association between HLA genes and SLE has been widely evaluated, the results are not often reproducible, and most studies are limited by small sample sizes and genetic heterogeneity.[12,14,15] It is universally recognized that individual studies in small sample size may have not enough statistical power to detect a small risk factor or give a fluctuated estimation. Genetic heterogeneity is an inevitable problem in any disease identification strategy that can be avoided when large homogeneous populations are used. To overcome these limitations and fill this gap in knowledge, we designed the present meta-analysis of all case-control studies in the medical literature to comprehensively assess the genetic association of HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms in HLA-DRB1 gene with the risk of having SLE.

METHODS

The conduct of this meta-analysis conformed to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.[16]

Literature search strategy

The electronic databases used for literature search included PubMed, Springer Link, Elsevier Science, and Cochrane Library database, and search process was conducted independently by two investigators (Xue K and Niu WQ), restricting the publications included to English language studies and humans only. The key words included “systemic lupus erythematosus” or “SLE” and “human lymphocyte antigen” or “HLA” or “HLA-DRB” or “HLA-DR3” or “HLA-DR15”. In addition, hand searching of the reference lists of retrieved articles was also conducted.

Study selection

Studies were included if they satisfied the following criteria: (1) the diagnosis of SLE according to the American College of Rheumatology 1979 or 1982 revised classification criteria; (2) study design: cross-sectional or nested case-control design; (3) raw data including odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were provided, or enough information to calculate OR was supplied in the study; and (4) the article was published in peer-reviewed journals as original contributions, rather than in the form of conference abstract or poster or case series or letter to the editor.

Data extraction

Two investigators (Xue K and Niu WQ) independently extracted data from each eligible study using a standardized data extraction form, and any discrepancies were resolved by adjudicated by a third investigator (Cui Y). The items extracted included the first author's family name, publication year, country or area where the study was performed, sample size, ethnicity, diagnostic method, genotyping method, and genetic distributions of HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms in SLE patients and controls.

Statistical analysis

In a random-effects model, the OR and 95% CI for the risk prediction of HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms for SLE were calculated. The Chi-squared test and inconsistency index (I2) statistic were used to quantify the heterogeneity of effect-size estimates both in overall and subgroup analyses. I2 statistics were used to quantify the percentage of the total variance between-study heterogeneity; Pm < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. 95% CIs were analyzed to determine the diagnostic accuracy of SLE.

The proportion of the total variation increases with the percentage of I2. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was test in control groups. Random-effects model was constructed to calculate the P value for heterogeneity. Based on the ascending order of publication dates, a cumulative analysis was performed to identify the impact of the first published study on the following publications and the evolution of the pooled estimates over time. Subgroup analysis and meta-regression analysis were conducted to estimate the potential confounding factors such as race, control source, and matched status between patients and controls. The Begg's funnel plot was employed to assess the probability of publication bias. The trim-and-fill method was employed to estimate the number of potentially missing studies caused by publication bias. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA software (Version 14.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Eligible studies

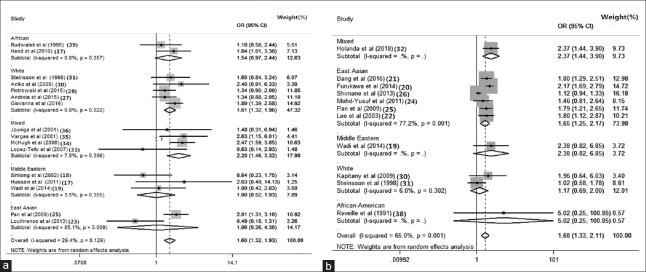

Based on literature search strategy, a total of 238 potentially relevant articles were identified. Among them, only 16 studies were eligible for the association of HLA-DR3 allele with the risk of SLE and 11 studies for the association of HLA-DR15. A flow diagram of the selection process with detailed reasons for exclusion is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy and study selection on polymorphisms of HLA-DRB1 gene with the risk of SLE. SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of all eligible studies in this meta-analysis are presented in Table 1. Twenty-three studies including a total of 5261 patients with SLE and 9838 controls were used to evaluate the association of HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms with the risk of SLE. Among the 23 qualified studies, seven studies included East Asian populations,[17,18,19,20,21,22,23] five studies included White populations,[24,25,26,27,28] five studies included mixed populations,[29,30,31,32,33] three studies included Middle Eastern populations,[34,35,36] and three studies included African populations.[37,38,39] Ten studies involving SLE patients and controls matched on gender and age. Seven studies recruited controls from hospitals and 17 studies from populations.

Table 1.

Characteristicsof 23 studies included in the meta-analysis

| Author (year) | Ethnicity | Assessment method | Detection methods | Controlsource |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hend et al. (2018)[36] | African | ARC | PCR-SSP | Hospital |

| Giovanna et al. (2016)[27] | White | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Piotrowski et al. (2015)[28] | White | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Andreia et al. (2015)[26] | White | ARC | PCR-SSP | Hospital |

| Louthrenoo et al. (2013)[22] | East Asian | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Wadi et al. (2014)[18] | Middle Eastern | ARC | PCR-SSP | Hospital |

| Hussain et al. (2011)[16] | Middle Eastern | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Pan et al. (2009)[24] | East Asian | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Aniko et al. (2009)[29] | White | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Lopez-Tello et al. (2007)[32] | Mixed | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| McHugh et al. (2006)[33] | Mixed | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Sirikong et al. (2002)[17] | Middle Eastern | ARC | PCR-SSP | Hospital |

| Vargas et al. (2001)[34] | Mixed | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Steinsson et al. (1998)[30] | White | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Rudwaleit et al. (1995)[38] | African | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Jzuniga et al. (2001)[35] | Mixed | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Holanda et al. (2018)[31] | Mixed | ARC | PCR-SSP | Hospital |

| Bang et al. (2016)[20] | East Asian | ARC | PCR-SSP | Hospital |

| Furukawa et al. (2014)[19] | East Asian | ARC | PCR-SSP | Hospital |

| Shimane et al. (2013)[25] | East Asian | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Mohd-Yusuf et al. (2011)[23] | East Asian | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Lee et al. (2003)[21] | East Asian | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

| Reveille et al. (1991)[37] | African-American | ARC | PCR-SSP | Population |

After excluding studies, no changes in overall estimates were found which violated the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Overall analysis

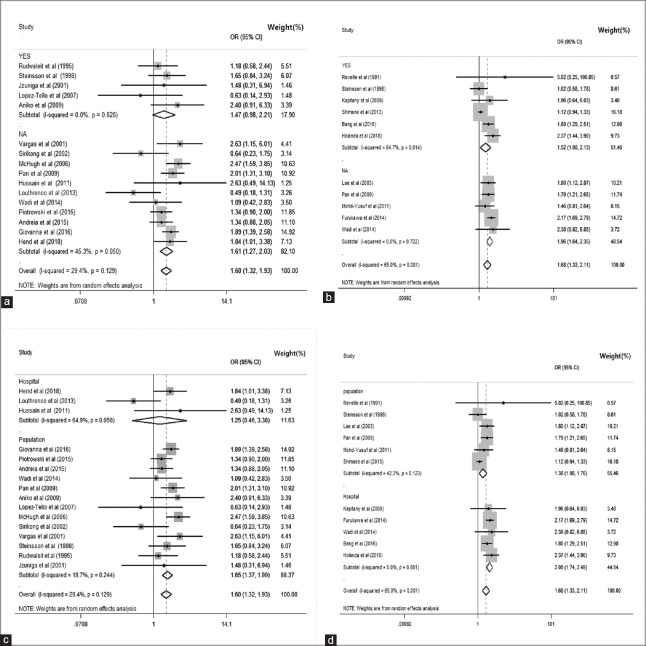

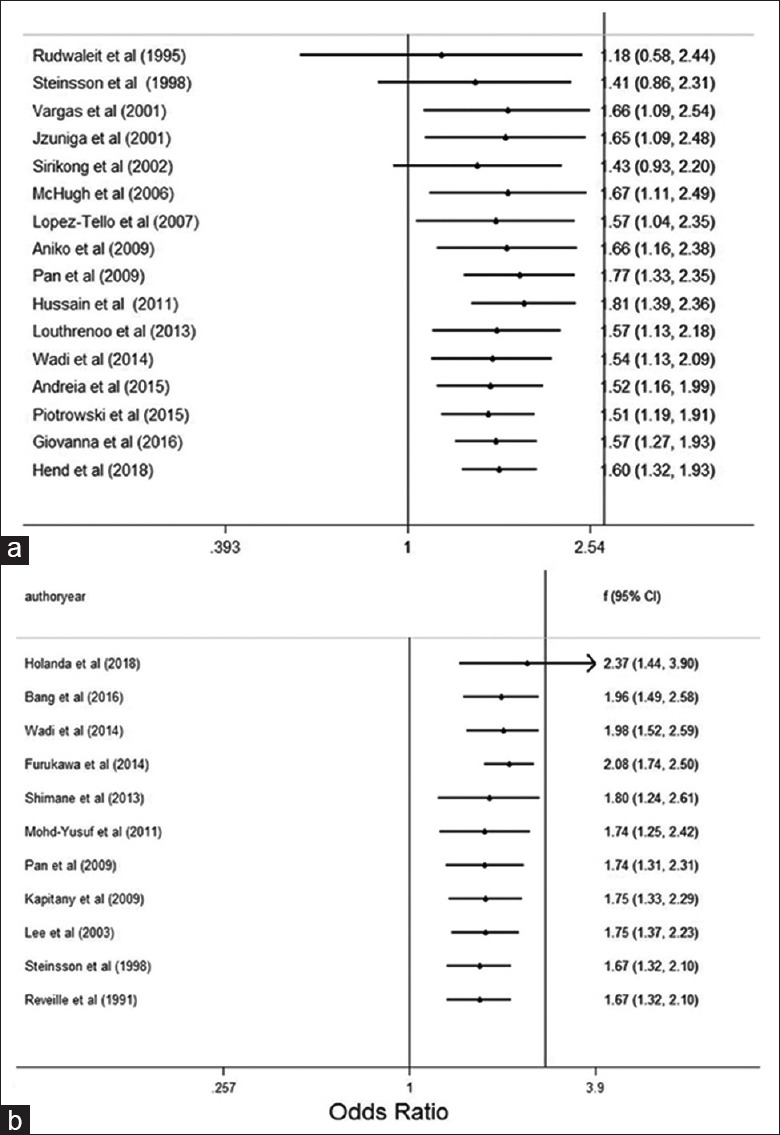

There were 16 and 11 studies with HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms, respectively. Under random-effects models, overall analysis revealed that HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms were associated with the significant risk of SLE (OR: 1.595, 95% CI: 1.316–1.934, P = 0.129 and OR: 1.678, 95% CI: 1.334–2.112, P = 0.001, respectively) [Figure 2a and 2b].

Figure 2.

Forest plots for meta-analysis of HLA-DRB1 gene. (a) Overall analysis association between HLA-DR3 polymorphisms and the significant risk of SLE. (b) Overall analysis association between HLA-DR15 polymorphisms and the significant risk of SLE. The ORs with 95% CI were calculated by the Mantel–Haenszel method. The gray squares represent the studies in relation to their weights. CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; I2: Higgins test.

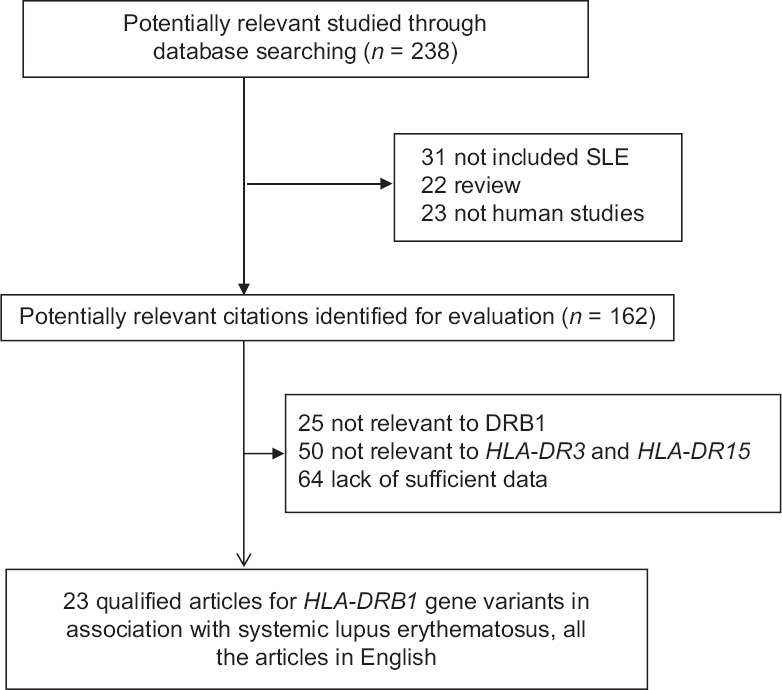

Subgroup analysis

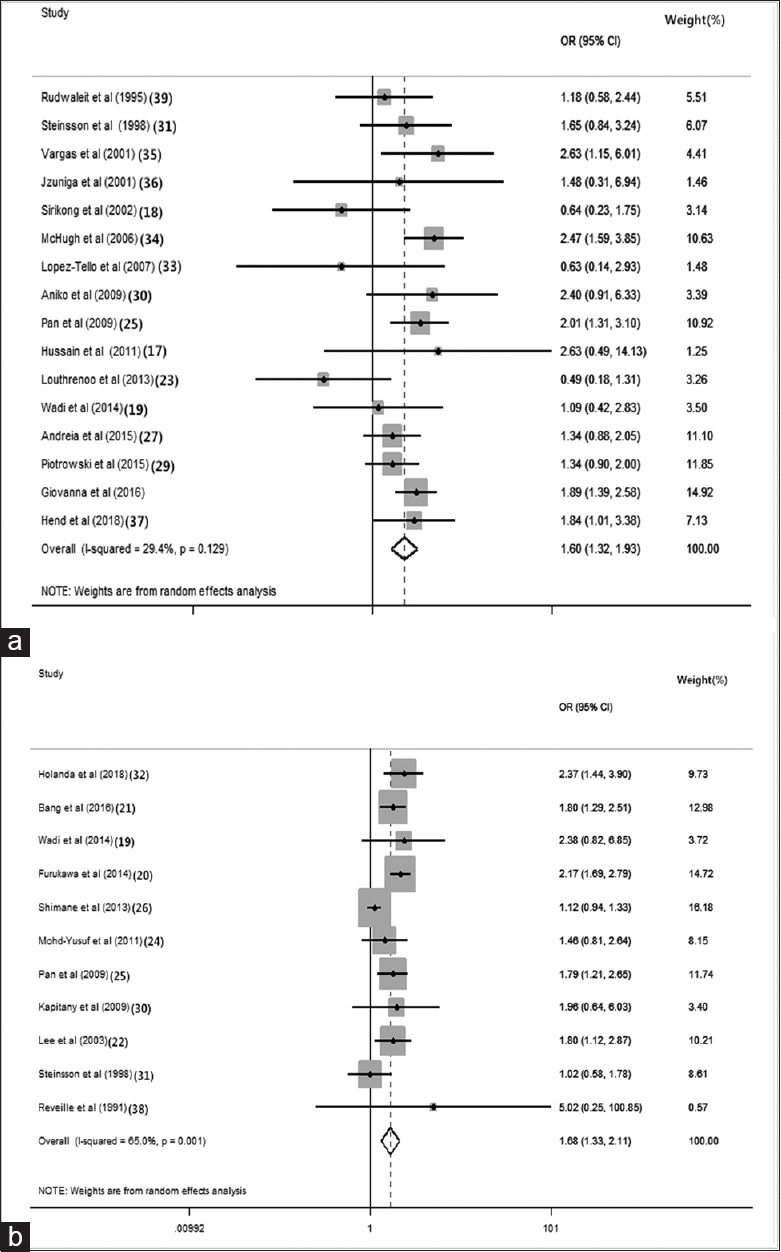

To explore potential sources of between-study heterogeneity, we conducted a set of subgroup analyses. In subgroup analysis for HLA-DR3 polymorphism, we found the following results: 47.32% (OR: 1.610, 95% CI: 1.320–1.960, P = 0.522) in White populations, 17.9% (OR: 1.470, 95% CI: 0.980–2.210, P = 0.626) in matched studies, and 88.37% (OR: 1.650, 95% CI: 1.370–1.990, P = 0.244) in studies involving population-based controls [Figures 3a, 4a and 4c].

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis forest plot of HLA by ethnicity. (a) The association between HLA-DR3 alleles and the significant risk of SLE with different ethnicity. (b) The association between HLA-DR15 alleles and the significant risk of SLE with different ethnicity. CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; I2: Higgins test.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis forest plot of HLA alleles with matching situation and hospital/population-sourced data. (a) Meta-analysis forest plot of HLA-DR3 alleles with matched or not applicable; (b) meta-analysis forest plot of HLA-DR15 alleles with matched or NA; (c) meta-analysis forest plot of HLA-DR3 alleles with hospital/population-sourced data; (d) meta-analysis forest plot of HLA-DR15 alleles with hospital/population-sourced data. SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus; CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; I2: Higgins test; NA: Not applicable.

For HLA-DR15 subgroup analyses, we found the following results: 73.98% (OR: 1.646, 95% CI: 1.248–2.173, P = 0.001) in East Asian populations, 51.46% (OR: 1.519, 95% CI: 1.084–2.130, P < 0.050) in matched studies, and 55.46% (OR: 1.378, 95% CI: 1.078–1.760, P = 0.123) in studies involving population-based controls [Figures 3b and 4b, 4d].

Cumulative analysis

The cumulative analysis for HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms in association with the risk of SLE was conducted, showing stable ORs and 95% CIs, and none of these studies affected pooled ORs and 95% CIs [Figure 5a and 5b]. The pooled estimates of the HLA-DR3 polymorphism remained stable with the accumulation of genetic data over time.

Figure 5.

Forest plot for cumulative analysis of HLA. (a) Forest plot for cumulative analysis of HLA-DR3; (b) forest plot for cumulative analysis of HLA-DR15. HLA: Human lymphocyte antigen.

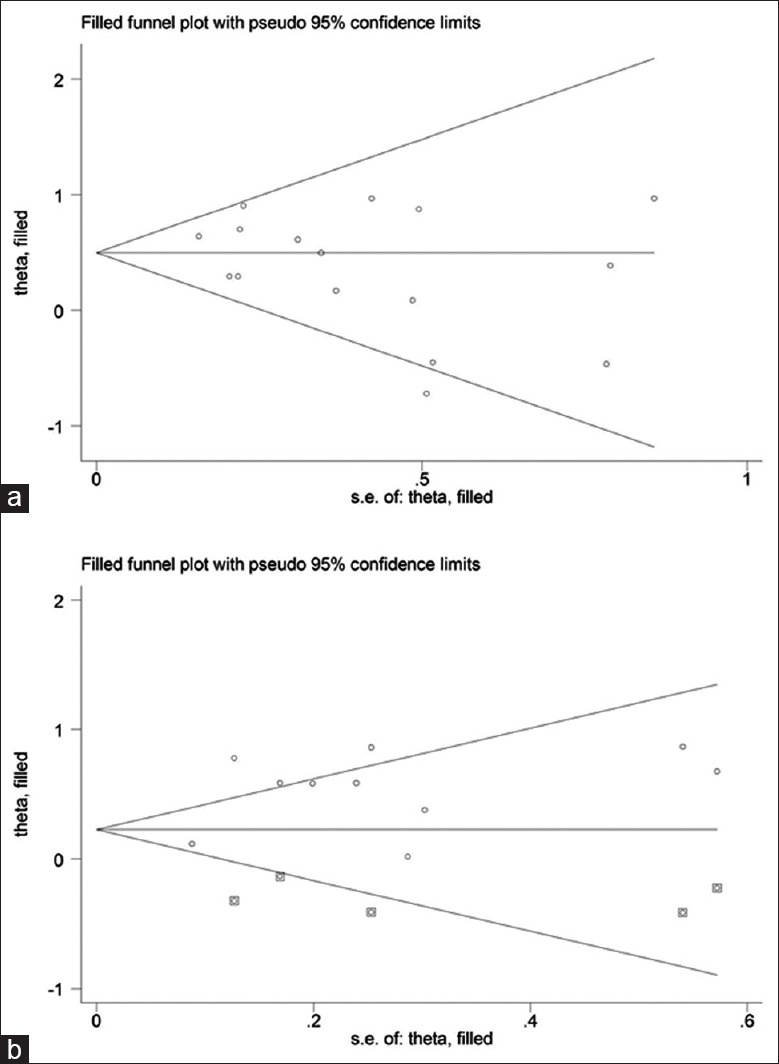

Publication bias

The probability of publication bias was justified by the Begg's funnel plots, which was proved to be relatively symmetric for both HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms. By contrast, five potentially missing studies were required to make the funnel plot symmetrical [Figure 6a and 6b].

Figure 6.

Fill funnel plots and Egger's linear regression test for publication bias. (a) Fill funnel plots for studies investigating the effect of HLA-DR3; (b) fill funnel plots for studies investigating the effect of HLA-DR15. Each spot represents a separate study. Hollow circles are the actual studies included in this meta-analysis, and solid squares are missing studies required to achieve symmetry.

DISCUSSION

It is well recognized that meta-analysis is a powerful tool to summarize results of individual studies, and it can increase statistical power and resolution.[40,41] In this present meta-analysis of published case-control studies, our findings indicated that HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms are associated with the significant risk of SLE, consistent with the results of most previous studies. The included literature usually does not report in detail to assess the validity and clinical characteristics of the preliminary study. It is best to avoid this in the initial trials. Unfortunately, for many of the biases in the study, such as poor distribution concealment, the precise effects are not known and cannot be corrected. To shed light on this issue, our subgroup analysis demonstrated that the association between HLA-DR3 polymorphism and SLE was significant in White populations, while the association between HLA-DR15 polymorphism and SLE was only significant in East Asian populations, indicating strong evidence of genetic heterogeneity across different racial or ethnical groups. A meta-regression model was built to explore other sources of between-study heterogeneity by combining covariates of various research levels. A large part of the heterogeneity for HLA-DR15 polymorphism under random-effects models was consistent with the results of subgroup analysis of differences in hospital or population (regression coefficient: 0.43; P = 0.003). The race source (coefficient: 0.151; P = 0.051) and other factors (matched or not applicable [NA]: coefficient: −0.276; P = 0.091) contributed no heterogeneous with SLE. As meta-regression analysis involved the limitation of sample size, it may not be fully to detect differences in small or moderate sample. Unfortunately, in this HLA-DR3 meta-analysis, randomized effector regression analysis showed no significance for these polymorphisms. It is important to remind that meta-regression does not have the methodological rigor of a designed study that is tended to test the effect of these covariates. Sensitivity analysis showed that none of the studies influenced the overall results significantly [Supplementary Figure 1a (393.1KB, tif) and 1b (393.1KB, tif) ]. There are several causes of heterogeneity: artefactual, methodological, and clinical. It will not always be possible to examine all sources of clinical heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis of HLA. (a) Sensitivity analysis of HLA-DR3; (b) sensitivity analysis of HLA-DR15.

SLE is a complex multistep and multifactorial disease. There is strong evidence for a genetic component in the pathogenesis of SLE.[1,2,4] HLA proteins regulate the immune response of autoreactive T-cells that can help B-cells to recognize the same autoantigen and produce autoantibodies, further resulting in the multisystem organ damage.[1,2] A large panel of case-control studies and meta-analyses have been undertaken and demonstrated that in HLA, genetic variation represents a major susceptibility factor for SLE. However, many previous studies are limited by insufficient sample sizes, which may lead to unstable or fluctuated effect-size estimates. Meta-analysis is deemed as a good method widely used for gathering results from individual studies with the same objectives. We thus performed a comprehensive meta-analysis of all available case-control studies to assess the association of two polymorphisms, HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 in HLA-DRB1 gene with the risk of having SLE in the medical literature.

A series of case-control studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that HLA-DRB1 is one of the most important susceptibility genes in SLE pathogenesis. For instance, HLA-DR3, HLA-DR9, and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms were identified as significant risk factors for SLE, while HLA-DR4, HLA-DR11, and HLA-DR14 polymorphisms were identified as protective factors for SLE. In the present meta-analysis, integrating 23 studies including 5261 patients and 9838 controls, we found that HLA-DR3 showed an OR of 1.595 (P < 0.01) and HLA-DR15 showed OR of 1.678 (P = 0.001), indicating the susceptibility of HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms to SLE.

To explore potential sources of heterogeneity across studies, we conducted a set of subgroup analyses, such as by ethnicity. Ethnic and genetic heterogeneities have been reported leading to the complexity of its clinical presentation.[12] Many meta-analyses demonstrated that ethnicity could affect the association between HLA gene polymorphisms and SLE predisposition. The distribution of HLA risk alleles and haplotypes and the association of HLA with the risk of SLE varied across racial and ethnical groups, and it is of importance to conduct genetic association studies in homogeneous populations.[12,14,15] In this study, for the HLA-DR3 subgroup analyses, 47.32% (OR: 1.611, P = 0.522) in White populations, and in the HLA-DR15 subgroup analyses, 73.98% (OR: 1.646, P < 0.01) in East Asian populations, indicating that HLA-DR3 was a risk factor for the development of SLE in White populations and HLA-DR15 in East Asian populations. This study further revealed that the frequencies of the HLA-DRB1 polymorphisms in SLE patients differed remarkably across ethnic groups.

Why the frequency of the HLA-DRB1 polymorphisms in SLE patients may be different across ethnic groups? A recent study showed that HLA-DR3 could restrict T-cell epitope on SmD79–93 (one of the SmD proteins) to activate T-cells reactive, thereby inducing autoimmune response to lupus-associated antigen SmD in SLE.[42] SmD79–93 and its molecular mimics could induce autoantibodies against SmD in SLE, which have been demonstrated mainly in lupus patients of North America.[43] This might explain why the association between HLA-DR3 and SLE patients was significant in White populations in this present meta-analysis. Moreover, the significant association between HLA-DR15 and SLE in East Asian populations indicated that there may be similar mechanism for HLA-DR15 regulating T-cell immune response in SLE of East Asian populations, which is worth for further investigations.

Some limitations need to be acknowledged in this meta-analysis. First, a wide range of articles to identify the role of HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 gene polymorphisms in SLE development were included in our study, and some specific differences existed within these articles that may lead to a potential source of bias. Second, all available articles in this study were published data; there may be some relevant articles with insufficient raw data or some unpublished studies with negative results which were not identified in our meta-analysis. Although no hints of publication bias were noticed in this meta-analysis, publication bias cannot be excluded absolutely. Third, although control groups of selected articles in our meta-analysis were mainly healthy, some specific genetic effects may exit. Moreover, it could not be entirely ruled out that whether these genetic effects will influence SLE incidence in the future. Fourth, although significant heterogeneity of HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms in different population was demonstrated in this meta-analysis, several other reasons may account for the heterogeneity, such as endocrine immunologic and environmental factors. Thus, more functional studies or meta-analyses should be performed to figure out this question in the future. Fifth, based on our analyses of ethnicity, matched status, and source of control groups, the association of HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms with lupus nephritis or other complications was not included.

In summary, our findings indicate that HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR15 polymorphisms are significantly associated with the risk of SLE. Based on ethnicity analysis, we further found that the association between HLA-DR3 and SLE was significant in White populations, while the association between HLA-DR15 and SLE was significant in East Asian populations. Our results enrich the repertoire of HLA genes that have potential roles in the pathogenesis of SLE, and we agree that more biological studies are needed to further confirm these associations and explain different association of different population.

Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Chinese Medical Journal website.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by grants from the National Key Basic Research Program of China (No. 2014CB541901), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 81573033), and the National Key Research Program of China (No. 2016YFC0906102).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Ning-Ning Wang

REFERENCES

- 1.Han EC. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:573–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1115196. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1115196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapoport M, Bloch O. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:574. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1115196. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1115196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Block SR, Winfield JB, Lockshin MD, D'Angelo WA, Christian CL. Studies of twins with systemic lupus erythematosus. A review of the literature and presentation of 12 additional sets. Am J Med. 1975;59:533–52. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(75)90261-2. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(75)90277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentham J, Morris DL, Graham DS, Pinder CL, Tombleson P, Behrens TW, et al. Genetic association analyses implicate aberrant regulation of innate and adaptive immunity genes in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1457–64. doi: 10.1038/ng.3434. doi: 10.1038/ng.3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gateva V, Sandling JK, Hom G, Taylor KE, Chung SA, Sun X, et al. Alarge-scale replication study identifies TNIP1, PRDM1, JAZF1, UHRF1BP1 and IL10 as risk loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1228–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.468. doi: 10.1038/ng.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han JW, Zheng HF, Cui Y, Sun LD, Ye DQ, Hu Z, et al. Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1234–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.472. doi: 10.1038/ng.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Consortium for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Genetics (SLEGEN) Harley JB, Alarcón-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA, Jacob CO, Kimberly RP, et al. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat Genet. 2008;40:204–10. doi: 10.1038/ng.81. doi: 10.1038/ng.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito I, Kawasaki A, Ito S, Hayashi T, Goto D, Matsumoto I, et al. Replication of the association between the C8orf13-BLK region and systemic lupus erythematosus in a Japanese population. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:553–8. doi: 10.1002/art.24246. doi: 10.1002/art.24246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris DL, Sheng Y, Zhang Y, Wang YF, Zhu Z, Tombleson P, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in Chinese and European individuals identifies ten new loci associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2016;48:940–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.3603. doi: 10.1038/ng.3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghodke-Puranik Y, Niewold TB. Immunogenetics of systemic lupus erythematosus: A comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2015;64:125–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.08.004. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sestak AL, Fürnrohr BG, Harley JB, Merrill JT, Namjou B. The genetics of systemic lupus erythematosus and implications for targeted therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(Suppl 1):i37–43. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138057. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong M, Tsao BP. Current topics in human SLE genetics. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2006;28:97–107. doi: 10.1007/s00281-006-0031-6. doi: 10.1007/s00281-006-0031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castaño-Rodríguez N, Diaz-Gallo LM, Pineda-Tamayo R, Rojas-Villarraga A, Anaya JM. Meta-analysis of HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DQB1 polymorphisms in Latin American patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7:322–30. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.12.002. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smikle M, Christian N, DeCeulaer K, Barton E, Roye-Green K, Dowe G, et al. HLA-DRB alleles and systemic lupus erythematosus in Jamaicans. South Med J. 2002;95:717–9. doi: 10.1097/00007611-200295070-00011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerbase-Delima M, Pinto LC, Grumach A, Carneiro-Sampaio MM. HLA antigens and haplotypes in IgA-deficient Brazilian paediatric patients. Eur J Immunogenet. 1998;25:281–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2370.1998.00098.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1988.tb01659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussain N, Jaffery G, Sabri AN, Hasnain S. HLA association in SLE patients from Lahore-Pakistan. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2011;11:20–6. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2011.2618. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2011.2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sirikong M, Tsuchiya N, Chandanayingyong D, Bejrachandra S, Suthipinittharm P, Luangtrakool K, et al. Association of HLA-DRB1*1502-DQB1*0501 haplotype with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in Thais. Tissue Antigens. 2002;59:113–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.590206.x. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.590206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wadi W, Elhefny NE, Mahgoub EH, Almogren A, Hamam KD, Al-Hamed HA, et al. Relation between HLA typing and clinical presentations in systemic lupus erythematosus patients in Al-Qassim region, Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2014;8:159–65. doi: 10.12816/0006082. doi: 10.12816/0006082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furukawa H, Kawasaki A, Oka S, Ito I, Shimada K, Sugii S, et al. Human leukocyte antigens and systemic lupus erythematosus: A protective role for the HLA-DR6 alleles DRB1*13:02 and *14:03. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim K, Bang SY, Yoo DH, Cho SK, Choi CB, Sung YK, et al. Imputing variants in HLA-DR beta genes reveals that HLA-DRB1 is solely associated with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee HS, Chung YH, Kim TG, Kim TH, Jun JB, Jung S, et al. Independent association of HLA-DR and FCgamma receptor polymorphisms in Korean patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:1501–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg404. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Louthrenoo W, Kasitanon N, Wichainun R, Wangkaew S, Sukitawut W, Ohnogi Y, et al. The genetic contribution of HLA-DRB5*01:01 to systemic lupus erythematosus in Thailand. Int J Immunogenet. 2013;40:126–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2012.01145.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2012.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohd-Yusuf Y, Phipps ME, Chow SK, Yeap SS. HLA-A*11 and novel associations in Malays and Chinese with systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol Lett. 2011;139:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2011.05.001. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan CF, Wu CJ, Chen HH, Dang CW, Chang FM, Liu HF, et al. Molecular analysis of HLA-DRB1 allelic associations with systemic lupus erythematous and lupus nephritis in Taiwan. Lupus. 2009;18:698–704. doi: 10.1177/0961203308101955. doi: 10.1177/0961203308101955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimane K, Kochi Y, Suzuki A, Okada Y, Ishii T, Horita T, et al. An association analysis of HLA-DRB1 with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis in a Japanese population: Effects of *09:01 allele on disease phenotypes. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:1172–82. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes427. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bettencourt A, Carvalho C, Leal B, Brás S, Lopes D, Martins da Silva A, et al. The protective role of HLA-DRB1(*) 13 in autoimmune diseases. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:948723. doi: 10.1155/2015/948723. doi: 10.1155/2015/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cruz GI, Shao X, Quach H, Ho KA, Sterba K, Noble JA, et al. Achild's HLA-DRB1 genotype increases maternal risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2016;74:201–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.06.017. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piotrowski P, Wudarski M, Sowińska A, Olesińska M, Jagodziński PP. TNF-308 G/A polymorphism and risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in the Polish population. Mod Rheumatol. 2015;25:719–23. doi: 10.3109/14397595.2015.1008778. doi: 10.3109/14397595.2015.1008778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapitany A, Tarr T, Gyetvai A, Szodoray P, Tumpek J, Poor G, et al. Human leukocyte antigen-DRB1 and -DQB1 genotyping in lupus patients with and without antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:545–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04642.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinsson K, Jónsdóttir S, Arason GJ, Kristjánsdóttir H, Fossdal R, Skaftadóttir I, et al. A study of the association of HLA DR, DQ, and complement C4 alleles with systemic lupus erythematosus in Iceland. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:503–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.8.503. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.8.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Holanda MI, Klumb E, Imada A, Lima LA, Alcântara I, Gregório F, et al. The prevalence of HLA alleles in a lupus nephritis population. Transpl Immunol. 2018;47:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2018.02.001. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.López-Tello A, Rodríguez-Carreón AA, Jurado F, Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Castillo-Vázquez M, Chávez-Muñoz C, et al. Association of HLA-DRB1*16 with chronic discoid lupus erythematosus in MEXICAN mestizo patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:435–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02391.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McHugh NJ, Owen P, Cox B, Dunphy J, Welsh K. MHC class II, tumour necrosis factor alpha, and lymphotoxin alpha gene haplotype associations with serological subsets of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:488–94. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.039842. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.039842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vargas-Alarcón G, Salgado N, Granados J, Gómez-Casado E, Martinez-Laso J, Alcocer-Varela J, et al. Class II allele and haplotype frequencies in Mexican systemic lupus erythematosus patients: The relevance of considering homologous chromosomes in determining susceptibility. Hum Immunol. 2001;62:814–20. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(01)00267-1. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(01)00267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zúñiga J, Vargas-Alarcón G, Hernández-Pacheco G, Portal-Celhay C, Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Granados J. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter polymorphisms in Mexican patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Genes Immun. 2001;2:363–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363793. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hachicha H, Kammoun A, Mahfoudh N, Marzouk S, Feki S, Fakhfakh R, et al. Human leukocyte antigens-DRB1*03 is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus and anti-SSB production in South Tunisia. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2018;12:21–7. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(01)00267-1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reveille JD, Barger BO, Hodge TW. HLA-DR2-DRB1 allele frequencies in DR2-positive black Americans with and without systemic lupus erythematosus. Tissue Antigens. 1991;38:178–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1991.tb01892.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1991.tb01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudwaleit M, Tikly M, Gibson K, Pile K, Wordsworth P. HLA class II antigens associated with systemic lupus erythematosus in black South Africans. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:678–80. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.8.678. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.8.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang JY, Tian GH, Li YP, Wu TX, Bian ZX, Du L, et al. Systematic reviews/meta-analyses of integrative medicine in Chinese need regulation and monitoring urgently and some suggestions for its solutions. Chin J Integr Med. 2018;24:83–6. doi: 10.1007/s11655-017-2427-7. doi: 10.1007/s11655-017-2427-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uman LS. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:57–9. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-415794-1.00013-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deshmukh US, Sim DL, Dai C, Kannapell CJ, Gaskin F, Rajagopalan G, et al. HLA-DR3 restricted T cell epitope mimicry in induction of autoimmune response to lupus-associated antigen Smd. J Autoimmun. 2011;37:254–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.07.002. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Migliorini P, Baldini C, Rocchi V, Bombardieri S. Anti-Sm and anti-RNP antibodies. Autoimmunity. 2005;38:47–54. doi: 10.1080/08916930400022715. doi: 10.1080/08916930400022715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sensitivity analysis of HLA. (a) Sensitivity analysis of HLA-DR3; (b) sensitivity analysis of HLA-DR15.