Abstract

Sweeping social change is occurring in India with regard to the proposed transgender legislation and the enshrinement of associated rights. This progressive legislative change occurs as existing Indian law is profoundly reshaped by the judiciary with regard to other members of this sexually diverse group, the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) group. Now as a group of immense interest within high-income countries, this article through Government, legal, and medical literature, explores the possible population of interest in India, relevant law and associated health disparities. The author considers the evidence of a mental health burden, among the estimated 45.4 million LGBT people in 2011. The complex contribution of psychiatrists is noted, and a prism for care delivery is suggested. The underlying goal of lower morbidity for the entire LGBT community is through enhanced care opportunities, understanding, and reduced societal discrimination.

Keywords: CanMEDS, gender, inequity, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender

BACKGROUND

The remnants of India's colonial past are carried today in systems that have styled inequities that create a clear health burden for some Indian citizens. European hegemony has long ended and a global world of communication, evidence, and a deeper understanding of the interaction of our traditional cultural heritage, and roles have produced new vistas for all of us, as participants in this future world. The role of medical specialists, and in particular, of psychiatrists is integral to assisting our communities. As experts, we often assist society during the navigation of major transitions while safeguarding the mental health of members of our communities and informing the community as a whole.

On one issue, The Republic of India, the second most populous country on earth, has until now been out of step. Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code of 1860 made homosexual intercourse an offense.[1] This law borne of Britain is extinguished in the country of its origin. The 2012 Delhi High Court challenge to this law through Naz Foundation v. Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi found that this position was a violation of fundamental rights provided by the Indian Constitution, but this decision was reviewed and effectively reversed.[2] In the attempts to overturn the Delhi High Court challenge, arguments were made that this legislation affected very few people. Section 377 thus remained in place until 2018. Yet, a contrary argument also emerged, and along with it, that this group may have social needs.[3]

The Supreme Court decision to finally overturn Section 377 (in Navtej Singh Johar and Ors versus Union of India, The Secretary Ministry of Law and Justice) on September 6, 2018, is a deeply humanistic one. Amid the 495-page judgment, with broad constitution reach, Chief Justice Dipak Misra and Justice AM Khanwilkar's on page 6 write:

“The natural identity of an individual should be treated to be absolutely essential to his being. What nature gives is natural. That is called nature within. Thus, that part of the personality of a person has to be respected and not despised or looked down upon. The said inherent nature and the associated natural impulses in that regard are to be accepted. Nonacceptance of it by any societal norm or notion and punishment by law on some obsolete idea and idealism affects the kernel of the identity of an individual. Destruction of individual identity would tantamount to crushing of intrinsic dignity that cumulatively encapsulates the values of privacy, choice, freedom of speech, and other expressions. It can be viewed from another angle. An individual in the exercise of his choice may feel that he/she should be left alone but no one, and we mean, no one should impose solitude on him/her.”[4]

This victory of constitutional jurisprudence will now extend to almost all of India. Importantly, it is also a victory for the individual amid the crowd.

There may be one regional exception with similar criminal offenses against gay sex still remaining in the state of Jammu and Kashmir that has the Ranbir Penal Code, and a separate constitution.[5]

With a focus on this group, can we make sense of matters and distill if there are specific health needs?

In considering how we can approach this challenge, as psychiatrists within our region, we need to frame the challenge as a series of questions. What is the possible population under consideration? What is the possible issue of concern? Can I obtain objective evidence from a reliable source outside of the country, such as the United Nations (UN)? What are the core qualities of a specialist? Thus, how should a specialist act? What are other countries doing? Specifically, are there other examples from the Asia Pacific region? And do we already have examples of excellence in our own country that can serve as models of strength?

LEARNING ABOUT THE LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER POPULATION IN INDIA

The 2011 census identified at least 1210 million Indian citizens, with reports from the censusindia that the population is continuing to grow.[6] Censusindia also introduced a new category for the first time in the 2011 census with the move away from the binary perspective of gender with three options: “female,” “male,” and “other.” No accurate figures exist for the size of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) population. Prejudice and fear prevent disclosure of identity in many instances, and thus, population estimates are difficult to predict.

The most reliable data are derived from populations that are not Indian. High-income countries with reporting measures are sources of interest. In 2011, the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that 1% of all couples in Australia were prepared to disclose that they were in a same-sex relationship,[7] but in one study, far greater numbers were prepared to report same-sex attraction with women 15% and men 9% of the same sex attracted.[8] The United States of America has a diverse and large immigrant population with 41 million known immigrants in 2011, and almost one in four children in the USA have at least one foreign-born parent.[9] In 2011, Gates, of the Williams Institute, University of California, Los Angeles School of Law, estimated the LGBT population of the United States, with estimates calculated from a large number of international studies that used large cohorts of people, sometimes longitudinally sampled. This research and its conclusions are widely cited, estimating that 3.5% of adults are lesbian, gay, or bisexual, while 0.3% are transgender. Specific sex estimates are female – 2.2% bisexual and 1.1% lesbian; male – 1.4% bisexual and 2.2% gay. This may still be underreporting as participants may be unwilling to report the status of their sexuality.[10]

Of interest, very specific information is available, in India, about the transgender group with legislation enacted providing rights and protection. The Rights of Transgender Persons Bill, 2014, passed the Rajya Sabha (Upper House of the Indian Parliament) on April 24, 2015. It is currently before the Lok Sabha (Lower House). The Act guarantees many rights for Transgender Indians, including access to education, employment, housing, medical care, and freedom from discrimination. It includes consideration about the need for curriculum review and enhanced medical education, to equip the workforce with the competency required to meet the needs of this population. This is extremely forward thinking. Of great importance, the Act highlights the familial bond and the primacy of a sense of self-identity. It also mentions the pivotal role that a psychiatrist may play and refers to other professional groups.[11]

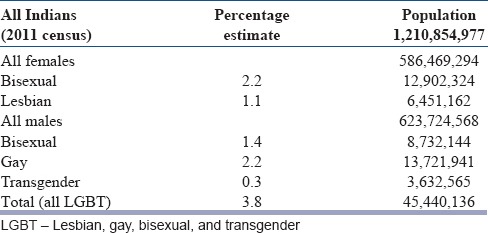

It is highly probable that the size of the LGBT population in India is no different to that of other national cohorts. The rich diversity of a large country of immigrants such as the United States also provides the best proxy.[10] Thus, if India is similar to the populations encountered in research in the developed countries, where estimates are gained, when participants are not in immense fear for being members of the LGBT group and can report with some level of freedom, it may be that 3.8% of the population[10] of India fall within the LGBT group, an estimated 45.4 million people in 2011, based on the last national Indian census.[6] Table 1 shows the estimated LGBT population of India 2011 (based on the Gates, Williams Institute Estimates).

Table 1.

Estimated lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender population of India 2011

It must be noted that the cultural experience of an LGBT person in India may be vastly different to someone in the USA; yet, the experience of discrimination and invalidation because of membership of the LGBT group may share common themes.

THE HEALTH OF LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER INDIVIDUALS

LGBT individuals generally experience a life where they are told their wishes, hopes, and dreams do not match the expectations and desires of those around them. Their own wishes may also be egodystonic as they feel deep regret about their inability to meet the familial and historic traditions that have been gifted to them. Navigating a life without role models and against the tide is very difficult. The term minority stress has often been used to describe this experience of navigating a life from this position.[12] Legal prohibitions against your very existence only heighten this stress.

The rates of depression, anxiety, and suicide are far greater in LGBT individuals.[13] The rates of suicidal ideation and attempts in the transgender group are extremely high.[14] This is a significant health gap, a true health inequity that is reversible. It is a not a symptom of being LGBT but an imposed social product.

Conversion therapies offer to change the sexual orientation of someone who is homosexual to heterosexual. Such therapies have previously been delivered by our profession, the psychological profession, and are still offered by religious groups, but they are now widely discredited (and often banned in some jurisdictions). They may also be harmful to patients who seek our care.[15,16]

THE UNITED NATIONS POSITION ON LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER RIGHTS AND HEALTH

In 2016, the UN appointed an independent expert on human rights for the LGBT community. The purpose is to report on discrimination and violence globally. Spokesman for the UN Stéphane Dujarric commented: “It is clear that there's still so much that needs to be done to protect people from violence, tackle discrimination at work, end bullying in schools, and ensure access to health care, housing, and essential services.” This supports the notion of a health inequity at a global level.[17]

QUALITIES OF A SPECIALIST

The CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (this includes psychiatrists) provides a very clear model to articulate our role as specialist doctors. The six building blocks of CanMEDS come together to define a medical expert which are as follows: professional, communicator, scholar, collaborator, health advocate, and leader.[18] This Canadian system of framing the role of a specialist has been widely adopted across many countries. Reflecting on the health inequities facing the LGBT population in India, it is very clear that as psychiatrists, we need a range of skills to work with patients, to understand their predicament, to advocate for them, and to provide expert leadership within our communities.

Identifying LGBT patients and their needs is important. Do we see people for who they are, or who we want them to be? LGBT patients may not readily disclose their status. If they do, understanding the cultural expectations that we may bring to the relationship and our countertransference can assist in providing the best possible care.

When taking personal histories, we can remove gender bias by asking patients open questions. For example, “Can you tell me about the history of your romantic relationships?” or “what's your partner's name?” rather than “what's your wife's name?” That works well in the developed western world. This approach, of course, needs to be styled to the appropriate sociocultural context and language of the patient.

THE INTERNATIONAL MOVEMENT IN LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER RIGHTS AND THE RECOGNITION OF SPECIFIC HEALTH-CARE NEEDS

The rise in marriage equality (where two individuals regardless of gender can marry each other), among many high- and middle-income countries, echoes the increased understanding of needs in this group. An interest in the health disparities has been an important motivator for this legislative change. The impact of discrimination on physical health has been less well understood than the profound impact on mental health. Specific pieces of evidence continue to emerge such as the decrease in adolescent suicide attempts in the United States following the state same-sex marriage policies (762,678 students).[19] This is reflected in multiple other studies where the absence of marriage equality has been demonstrated to be a mental health issue because it is a discriminatory burden.[20]

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists released Position Statement 83 Recognising and meeting the needs of the LGBT intersex population in 2016. This statement formally frames the position of the 4000 psychiatrists and 1500 trainees in the two countries. The statement considers the historical context, epidemiology, evidence, sociocultural prisms, and the specific health needs across the age spectrum. It was developed after wide consultation and makes a number of recommendations.[21]

The economic benefit of a fully inclusive society that supports individuals and their inherent identity is increasingly valued by business. The interconnections between the workplace and well-being have seen Australian businesses rally behind the support for marriage equality, and the recognition of LGBT equality in the workplace, to increase harmony and productivity.[22] In 2016, the Prime Minister of Australia attended the annual LGBT Mardi Gras Parade in Sydney, a street event of national significance.

Yet, the greatest example that the world is changing in this sphere, and led by the Indian diaspora, is Leo Varadkar, the Prime Minister of Ireland, who is the son of a man from Mumbai and is also openly gay.[23]

CONCLUSIONS

Psychiatrists in The Republic of India are not immune to the challenges facing the world. Sweeping social change is occurring across the developed world as LGBT individuals are accorded long-awaited human rights, and this is reflected in legislation. Among nations, India is a world leader in the legislative development of transgender rights. Indian constitutional jurisprudence has dispensed with colonial-era law and brought focus to the individual and restored rights for the LGBT person. There is a notable health disparity in this group, who experience major mental health morbidity, secondary to social pressures. As medical specialists, we can play a role in recognizing the individual and the specific needs of this group, while providing advocacy when possible, to close the health gap. As leaders in Asia, Indian psychiatrists are well positioned in this domain to improve health outcomes.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.The Indian Penal Code. ACT NO 45; 1860. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 11]. Available from: http://www.aiclindia.com/Acts/Indian%20Penal%20Code%201860.pdf .

- 2.Naz Foundation vs. Government of NCT of Delhi and Others. The High Court of Delhi at New Delhi, India: Naz Foundation vs. Government of NCT of Delhi and Others. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Philippines: Rappler; 2015. Dec 19, [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 11]. Rappler. India Parliament Blocks MP's Bill to Decriminalize Gay Sex. Available from: http://www.rappler.com/world/regions/south-central-asia/116433-india-blocks-mpvote-decriminalize-gay-sex . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navtej Singh Johar & Ors vs. Union of India, The Secretary, Ministry of Justice, The Supreme Court of India at New Delhi, India. 2018. [Last accessed on 2018 Sep 08]. Available from: https://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/realtime/sc_decriminalises_section_377_read_full_judgement.pdf .

- 5.India: 2018. Sep 08, [Last accessed on 2018 Sep 08]. The Times of India. SC Decriminalizes Gay Sex, but J&K will have to Wait Longer. Available from: https://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/section-377-pride-not-extended-to-jk/articleshow/65714300.cms . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Census India. The Office of the Registrar & Census Commissioner, India, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2011. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 11]. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/

- 7.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Social Trends, Same Sex Couples. 2011. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 11]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4102.0Main+Features10July+2013 .

- 8.Rosenstreich G. Revised 2nd ed. Sydney: National LGBTI Health Alliance; 2013. LGBTI People Mental Health and Suicide. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh GK, Rodriguez-Lainz A, Kogan MD. Immigrant health inequities in the United States: Use of eight major national data systems. Scientific World J. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/512313. [Doi: 10.1155/2013/512313] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gates GJ. UCLA: The Williams Institute; 2011. Apr, [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 11]. How Many People are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender? Available from: https://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/09h684x2 . [Google Scholar]

- 11.New Delhi, India: Lok Sabha, Indian Parliament; 2016. The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino Lesbian, Gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:346–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, et al. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in Lesbian, Gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer GR, Scheim AI, Pyne J, Travers R, Hammond R. Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: A respondent driven sampling study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:525. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1867-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royal College of Psychiatrists. Statement on Sexual Orientation Position Statement PS02/2014. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychological Association. Report of the Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.New York: 2016. Jul 01, [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 11]. UN Agrees to Appoint Human Rights Expert on Protection of LGBT. Available from: http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=54385#.WLEtvPl97IU . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J, editors. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raifman J, Moscoe E, Austin SB, McConnell M. Difference-in-differences analysis of the association between state same-sex marriage policies and adolescent suicide attempts. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:350–6. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kealy-Bateman W, Pryor L. Marriage equality is a mental health issue. Australas Psychiatry. 2015;23:540–3. doi: 10.1177/1039856215592318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melbourne: Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists; 2016. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Position Statement 83 Recognizing and Addressing the Mental Health Needs of the LGBTI Population. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sydney: [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 11]. The Sydney Morning Herald. Business is Gay Australia's Best Friend. Available from: http://www.smh.com.au/comment/business-isgay-australias-best-friend-20170228-gun1gv.html . [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Guardian. Ireland's First Gay Prime Minister Leo Varadkar Formally Elected. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jun/14/leo-varadkar-formally-elected-as-prime-minister-of-ireland .