Abstract

Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome (PHS) is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of the management of Parkinson's disease (PD). Central hypodopaminergic state which results due to abrupt withdrawal of dopaminergic medications in patients with PD is the postulated cause. Clinical manifestations of PHS are very akin to neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). Here, we report a case of a 60-year-old male with 13-year history of PD, who was on Levodopa (300 mg) + Carbidopa (75 mg). On abrupt stoppage of Levodopa (300 mg) + Carbidopa (75 mg), he presented with symptoms akin to NMS, with raised creatine kinase. As soon as the antiparkinsonian medications are reinstituted, the patient recovered completely. Literature in this area is limited to few case reports only. Existing literature recommends prompt reinstitution of antiparkinsonian medications as the mainstay of therapy for patients presenting with PHS.

Keywords: Hyperpyrexia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, Parkinson's disease, Parkinson's hyperpyrexia syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome (PHS), first described in 1981,[1] is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of the management of Parkinson's disease (PD).[2] It is an outcome of central hypodopaminergic state which results due to abrupt withdrawal of dopaminergic drug in patients with PD.[2] It is considered to be an underreported medical emergency that usually goes unrecognized due to its rare occurrence, and mild cases are often mislabeled as sepsis or worsening of parkinsonism.[3] Clinical manifestations of PHS are very akin to neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). The clinical picture is characterized by hyperpyrexia, rigidity, altered consciousness, dysautonomia, leukocytosis, and elevated creatine kinase (CK).[2] When not recognized in time, PHS is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.[2] Early recognition and prompt reintroduction of antiparkinsonian medications are keys to the successful management of this syndrome.[4]

Existing literature on PHS is still limited. In this report, we present a case of PHS and review the existing literature.

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old male presented to the emergency department in a state of altered sensorium. Exploration of history revealed that he has been suffering from hypertension and hypothyroidism for the last 15 years and was diagnosed with PD 13 years prior to presentation. Since being diagnosed with PD, he had been on a combination of levodopa and carbidopa combination (100 + 25 mg respectively thrice a day) and had been taking the medications with good compliance and following up regularly with the neurologist. A day prior to presentation to emergency department, the patient met a minor road traffic accident in which he sustained minor abrasions on the forearms. There was no associated history of head injury, vomiting, or any loss of consciousness. Due to the accident, he missed the afternoon dose of his antiparkinsonian medications. On the same day evening, he appeared a bit drowsy, confused, and also developed low-grade fever. He also started talking irrelevantly and misidentified the family members. Due to this, his antiparkinsonian medications were stopped by the family members; however, other medications were continued. By the next morning, his condition worsened further, and developed fever, altered sensorium, and respiratory difficulty, following which he was brought to the emergency department.

In the emergency department, on examination, he was found to have high-grade fever (103°F), cogwheel rigidity of all the four limbs, diaphoresis, and altered sensorium. In view of the history and examination findings, possibilities of encephalopathy and NMS were considered and he was investigated accordingly. There was no history of intake of any psychotropic medications or intake of any licit or illicit substance during this period. On investigation, his hemogram, liver function test, renal function test, serum electrolytes, blood culture, urine routine microscopy, and urine culture did not reveal any abnormality. Computerized tomography (CT) of the brain revealed diffuse cerebral atrophy. His serum Creatine Kinase (CK) level was raised, i.e., 3500 IU (normal range: 26–308 IU). Over the next 48 h, the patient's clinical condition worsened despite starting of bromocriptine 2.5 mg thrice a day. Due to respiratory difficulty, he required ventilatory support. In addition, his blood pressure fell down, and he required intravenous fluids and inotropes. He continued in the same state for another 48 h. In view of lack of response and inability to find any specific cause for his condition, his history was reviewed. Careful history revealed that his symptoms followed discontinuation of the antiparkinsonian agents and, as a result, PHP was suspected and he was restarted on antiparkinsonian medications, i.e., levodopa and carbidopa combination (100 + 25 mg respectively thrice a day) along with tablet bromocriptine 2.5 mg thrice daily along with continuation of supportive measures. Over the next 48 h, gradually, his condition started improving. His rigidity reduced significantly, fever subsided, did not require any ventilatory support, sensorium improved, started recognizing his family members, and the CK level came down to 700 IU. By the end of 5 days of reinstitution of antiparkinsonian medications, he recovered completely and his CK level came down to 29 IU. He was discharged in an improved state from the hospital and has been maintaining well on the antiparkinsonian medications for the last 6 months.

DISCUSSION

In the existing literature, PHS is also referred to as neuroleptic malignant-like syndrome (NMLS).[1] PHS is a medical emergency, which mimics the clinical picture of NMS or sepsis and is often missed. Diagnosis often becomes clear if a careful history of discontinuation of antiparkinsonian medication is elicited. In the index case too, possibilities of sepsis and NMS were considered initially, although there was no evidence of any localizing signs and symptoms of infection and there was no evidence of receiving any medications which could be linked to NMS. The index case presented with high fever, muscular rigidity, altered sensorium, and autonomic instability and on investigation was found to have raised CK levels. All these occurred in the background of acute stoppage of antiparkinsonian medications. Further, reinstitution of antiparkinsonian medications led to marked improvement in the clinical picture over a short span. All these features are consistent with the clinical picture of PHS in the literature. Existing literature suggests that if the diagnosis of PHS is delayed, it can be associated with complications such as acute renal failure, aspiration pneumonia, deep-venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.[2] In the index case, timely diagnosis prevented these complications.

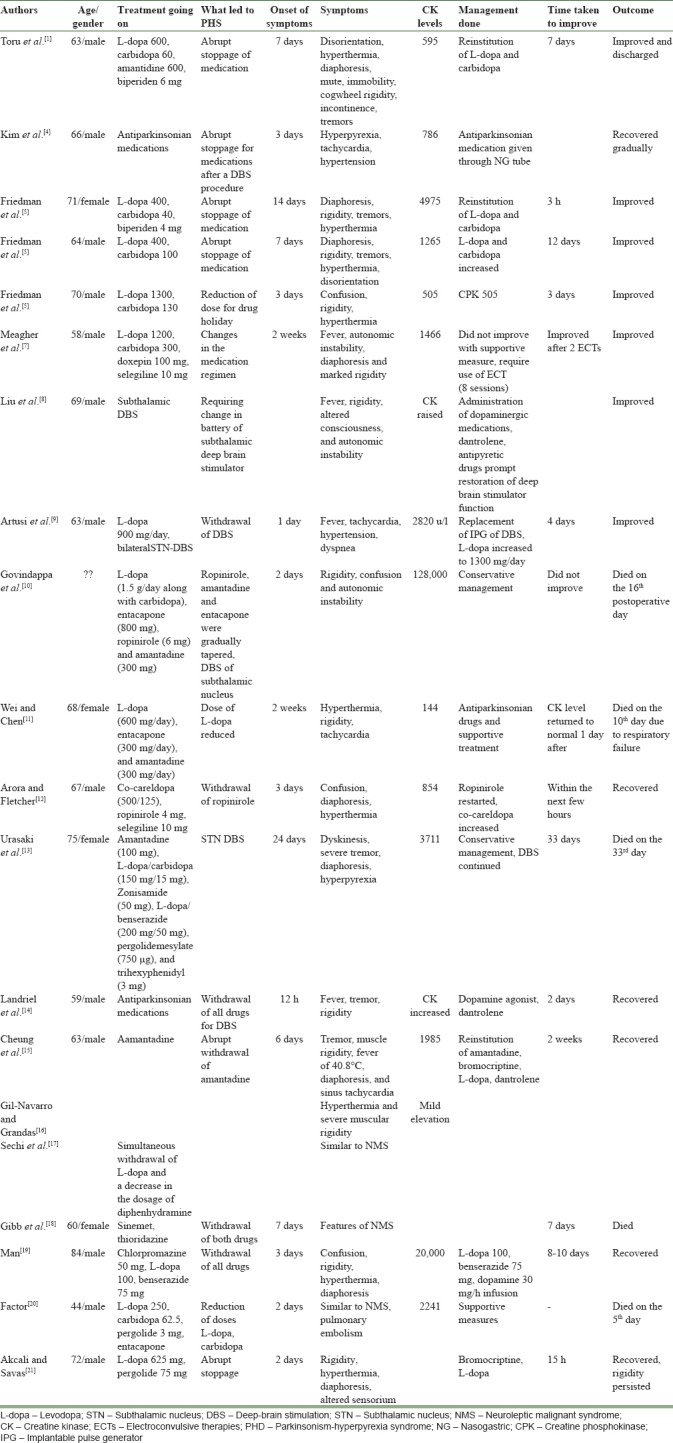

The concept of “levodopa/drug holiday” was considered to be the common cause of PHS in the 1980s.[6] However, drug holidays are not practiced anymore; hence, most of the cases reported in literature in recent times have been linked to discontinuation/reduction in the doses of antiparkinsonian medications. Overall, literature on PHS is limited. A PubMed search using keywords like “Parkinson Hyperpyrexia Syndrome” and “Parkinsonism Hyperpyrexia Syndrome” yielded twenty case descriptions [Table 1].[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] In most of these cases, PHS was precipitated by withdrawal/reduction or alteration of antiparkinsonian medications, including ropinirole;[12] withdrawal of deep-brain stimulation;[9] or exhaustion of battery of deep-brain stimulator.[8] In most of these reported cases, reinstitution of antiparkinsonian medications along with supportive measures led to improvement in the clinical picture in 15 h to about 2 weeks’ time. However, mortality was reported in occasional case reports,[6,10,11,13] and one case required the use of electroconvulsive therapy.[7] In the index case too, reinstitution of antiparkinsonian drugs along with supportive measures led to improvement in 5 days.

Table 1.

Existing case reports on parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome

Hypodopaminergic state is considered to be the underlying pathophysiology for PHS. Patients with PD are inherently dopamine depleted and hence, withdrawal of antiparkinsonian medication makes them more susceptible to PHS. The motoric manifestations of PHS are due to decreased dopaminergic activity in the nigrostriatal system. Hyperthermia is thought to be an outcome of hypodopaminergic state in dopamine pathways within the hypothalamus, i.e., preoptic area, the anterior hypothalamus related with thermal detection, and the posterior hypothalamus which generates effector signals. Dopaminergic depletion can also explain the altered mental status through modulation of mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways.[7]

It is important to remember that the phenotypic presentation of PHS and NMS is similar, but PHS is a distinct entity in that it is precipitated by stoppage of dopaminergic agents in patients with PD.[3]

CONCLUSION

The present case report and existing literature suggest that patients with PD should be warned of the possibility of PHS and advised against abrupt withdrawal of antiparkinsonian medications. Further, whenever a patient with PD presents with acute deterioration of symptoms, a possibility of PHS must be considered and careful history of medication compliance needs to be elicited. When diagnosed, the immediate measures must include reinstitution of antiparkinsonian medications and supportive measures.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images ands other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Toru M, Matsuda O, Makiguchi K, Sugano K. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome-like state following a withdrawal of antiparkinsonian drugs. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1981;169:324–7. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198105000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman EJ, Grosset DG, Kennedy PG. The parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome. Neurocrit Care. 2009;10:136–40. doi: 10.1007/s12028-008-9125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohammed NB, Sannegowda RB, Hejamadi MI, Sharma B, Dubey P. Single dose does matter! An interesting case of Parkinson's hyperpyrexia syndrome. J Neurol Disord. 2014;2:191. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JH, Kwon TH, Koh SB, Park JY. Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome after deep brain stimulation surgery: Case report. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:E1029. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000367799.38332.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman JH, Feinberg SS, Feldman RG. A neuroleptic malignant like syndrome due to levodopa therapy withdrawal. JAMA. 1985;254:2792–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Factor S. In: Drug Induced Movement Disorders. 2nd ed. Factor S, Lang A, Weiner W, editors. Mount Kisco, NY: Blackwell Publishing; 2005. pp. 174–212. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meagher LJ, McKay D, Herkes GK, Needham M. Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome: The role of electroconvulsive therapy. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:857–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu CJ, Crnkovic A, Dalfino J, Singh LY. Whether to proceed with deep brain stimulator battery change in a patient with signs of potential sepsis and Parkinson hyperpyrexia syndrome: A Case report. A A Case Rep. 2017;8:187–91. doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Artusi CA, Merola A, Espay AJ, Zibetti M, Romagnolo A, Lanotte M, et al. Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome and deep brain stimulation. J Neurol. 2015;262:2780–2. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7956-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Govindappa ST, Abbas MM, Hosurkar G, Varma RG, Muthane UB. Parkinsonism hyperpyrexia syndrome following deep brain stimulation. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21:1284–5. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei L, Chen Y. Neuroleptic malignant-like syndrome with a slight elevation of creatine-kinase levels and respiratory failure in a patient with Parkinson's disease. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:271–3. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S59150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arora A, Fletcher P. Parkinsonism hyperpyrexia syndrome caused by abrupt withdrawal of ropinirole. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2013;74:698–9. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2013.74.12.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urasaki E, Fukudome T, Hirose M, Nakane S, Matsuo H, Yamakawa Y, et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome) after deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:740–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landriel EG, Ajler P, Ciraolo C. Deep brain stimulation surgery complicated by Parkinson hyperpyrexia syndrome. Neurol India. 2011;59:911–2. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.91380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung YF, Hui CH, Chan JH. Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome due to abrupt withdrawal of amantadine. Hong Kong Med J. 2011;17:167–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gil-Navarro S, Grandas F. Dyskinesia-hyperpyrexia syndrome: Another Parkinson's disease emergency. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2691–2. doi: 10.1002/mds.23255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sechi GP, Tanda F, Mutani R. Fatal hyperpyrexia after withdrawal of levodopa. Neurology. 1984;34:249–51. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibb WR, Griffith DN. Levodopa withdrawal syndrome identical to neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:59–60. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.62.723.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Man SP. An uncommon adverse effect of levodopa withdrawal in a patient taking antipsychotic medication: Neuroleptic malignant-like syndrome. Hong Kong Med J. 2011;17:74–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Factor SA. Fatal parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome in a Parkinson's disease patient while actively treated with deep brain stimulation. Mov Disord. 2007;22:148–9. doi: 10.1002/mds.21172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akcali A, Savas L. Malignant syndrome of two Parkinson patients due to withdrawal of drugs. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:77–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]