Abstract

Background:

Eating disorders (ED), once known to be a rarity are now commonplace all over the world. However, studies on ED in the Indian population are still very rare to come across.

Aim:

We made an attempt to study the prevalence of ED in the student population of Mysore, South India.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 1600 students aged 15–25 years and residing in Mysore were surveyed using two standardized questionnaires. Among the 417 students who scored higher in the questionnaires, 35 students were recruited as participants. Another 35 students with low scores were considered controls. A series of anthropometric measurements were conducted along with the establishment of a register on their well-being and family history. Hemoglobin (Hb) content was measured using a Hb test kit from Beacon Diagnostics Pvt., Ltd., India. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 14.01 software utilizing analysis of variance tool.

Results:

It was found that 26.06% of participants were prone to ED due to their abnormal eating attitudes. We also observed significant differences between the controls and participants in relation to various parameters such as weight, waist and hip circumferences, body mass index, basal metabolic rate, fat percentage. Hb content was normal in both controls and participants. The establishment of the register also revealed that the onset of menstruation differed significantly between the controls and participants.

Conclusions:

We arrived at the conclusion that ED are definitely prevailing among the students of Karnataka and have a profound effect on the mental and physical health of the students with eating discrepancies.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, eating disorders

INTRODUCTION

Eating disorders (ED) are all those disorders that include irregular or disturbed eating practices. They are characterized by either excessive intake or inadequate intake of food.[1] It usually sets off in the mind of an adolescent when he/she is exposed to overhyped fitness body images on television or other mass media networks.[2] These are later followed by laxative abuse, self- induced vomiting, starvation, over exercising and so on which subsequently manifest into a full-blown ED. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 ED may be classified into anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge ED (BED) and many more which are beyond the scope of this study.[3] A vast number of prevalence studies have been conducted on ED as a whole and also on individual ED. Most of these studies were conducted when ED were only raising their heads as future issues of high social concerns.

A study on BN in Ontario reported prevalence rates of 1.1% among women and 0.1% among men.[4] Results from a study at Zurich showed the prevalence rates to be 0.7% and 0.5% for AN and BN, respectively.[5] An investigation in South Africa revealed the presence of abnormal eating attitudes,[6] whereas in a South Australian population, 0.3% of BN and 1% of BED was clearly demonstrated.[7] A study conducted across six European countries revealed 0.48%, 0.51%, and 1.12% to be the prevalence rates for AN, BN, and BED, respectively.[8]

The psychopathology characteristic of ED is not only restricted to western societies but also is already a part of Asian cultures as well.[9] As proof to this, an earlier study showcased higher prevalence of BN among Asian girls (3.4%) than the Caucasian girls (0.6%) residing at Bradford.[10] Another study conducted at Lahore displayed the presence of BN (0.27%) in Pakistan.[11] Furthermore, it has also been confirmed that 7.4% of Singaporeans were at risk of developing an ED.[12] In a recent study conducted at Jordan, a complete absence of AN was observed. However, BN was present at 0.6%, BED at 1.8% and EDNOS at a massive 31%.[13]

In the Indian scenario, a study involving the examination of 210 medical students of Chennai using eating attitudes test (EAT) and BITE self-report questionnaires reported 14.8% of the study population to have syndrome of eating distress.[14] Similarly, another study conducted on a North Indian population revealed the prevalence of BN to be 0.4%.[15] The most recent and available data of a study conducted in India is a comparison of the prevalence of eating distress in different zonal female basketball players of India. The results showed that the east zone of India showed the highest prevalence closely followed by the north zone. The west and south zones did not show a high incidence of eating distress. South zone scored the least.[16]

Studies on prevalence and other parameters of ED have been conducted worldwide; however, limited studies have been conducted in India and none in Karnataka. In an academically growing population like that of Mysore, all conditions are ideal for ED to prosper. Student fraternity is a community which is most affected by peer pressure of maintaining their physique to the point of it becoming an obsession. The current student population of Mysore are exposed to pressures of various kinds and are also exposed to the lures of having a thin body. Due to the absence of prevalence reports and research in this field in Karnataka, we attempted to analyze the prevalence of ED in the student population of Mysore, Karnataka.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Human Ethical Clearance Committee of University of Mysore (IHEC-UOM No. 05/M. Sc/2013-14) followed by the recruitment of a total of 1600 students, aged between 15 and 25 years, belonging to different institutes of Mysore city from 2012 to 2014. Each student was requested to answer two questionnaires EAT-26[17] and binge eating scale (BES)[18] which assessed their eating habits and behaviors. The students who scored high in either of these questionnaires were then contacted for an interview, anthropometric measurements and testing for their hemoglobin content (Hb). Of 417 students who scored positive for eating discrepancies 35 students were recruited, of which 18 scored higher in EAT-26 and the rest 17 in BES. These students formed the participants in this study. Case–control data set was done against a control population who scored low in the questionnaires and had sound physical and mental health. Written informed consent was obtained from each participating student.

All these students were subjected to anthropometric measurements such as height, weight, waist circumference, waist-hip ratio (WHR), body mass index (BMI), basal metabolic rate (BMR), and fat percentage. Hb content was assessed using a Hb test kit from Beacon Diagnostics Pvt., Ltd., India. The data obtained was then analyzed using Statistical software SPSS version 14.01 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Mean and standard errors were used for comparisons. Analysis of variance was employed to find any significant difference existing between the different groups. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Both, the participants and controls, were interviewed to establish a register concerning their health status, pubertal onset, stress conditions, the prevalence of obesity and diabetes among their parents as well as general awareness of ED.

RESULTS

In our investigation, we found that 26.06% (417) of students in the surveyed population of 1600 students demonstrated eating discrepancies. One hundred and seventy female students, i.e., 10.6% of the total population scored high in EAT-26, and 8.88% (142) females scored higher in BES. Among male students, 3.06% (49) scored high in EAT-26 and 3.5%, i.e., 56 males scored higher in BES. The prevalence rate for binge eating distress was found to be 12.37%, and the presence of eating distress among Mysore student population using EAT-26 was 13.68%. Further diagnosis into full syndrome ED could not be made due to lack of diagnostic expertise with respect to the Indian population.

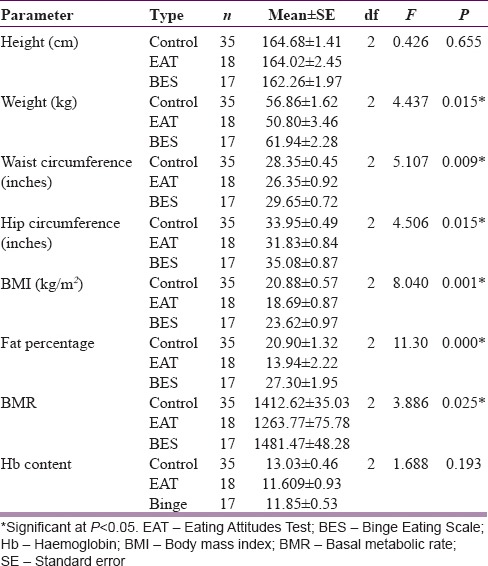

In general, all participants with high BES scores were significantly heavier than controls and EAT-26 scorers displayed lower weight than controls. Similar results were obtained in the parameters of the waist and hip circumference. About 11.4% of the participants exhibited higher WHR than the recommended value and belonged to the group of BES high scorers [Table 1]. Underweight, severely underweight, and very severely underweight individuals made up 16.6% each in the high scorers of EAT-26. The study revealed 23.5% of BES high scorers to be overweight and 11.7% to be moderately obese (Class I obesity). The mean BMI value of EAT-26 and BES high scorers were within the normal range by minute proportions. About 38.8% of females with high score in EAT-26 displayed low fat percentage than the required essential fat percentage, whereas 23.5% of females with high scores in BES showed higher fat percentage indicating obesity. The mean BMR of EAT-26 high scorers were lesser than the controls, whereas BES high scorers displayed higher BMR.

Table 1.

Comparison of mean values of different parameters between controls and high scoring subjects of Eating Attitudes Test-26 and Binge Eating Scale

Results for Hb content revealed normal Hb levels in high scorers of EAT-26 as well as high scorers of BES. However, 42.85% of our individual subjects were anemic. A significant variation (P < 0.05) between the groups was observed for various parameters such as weight, waist and hip circumferences, BMI, fat percentage, and BMR [Table 1].

On the establishment of a register after the interviews, we found that 60% of the participants complained of feeling stressed during work. 34.2% of these experienced mental stress. Another noteworthy revelation was 41.1% of the higher scorers of BES had at least one obese parent, and 35.2% had at least one parent who was diabetic. We also found that 29.4% of BES high scorers ate junk food on a regular basis while the rest preferred to mention it as a monthly binging on junk food items.

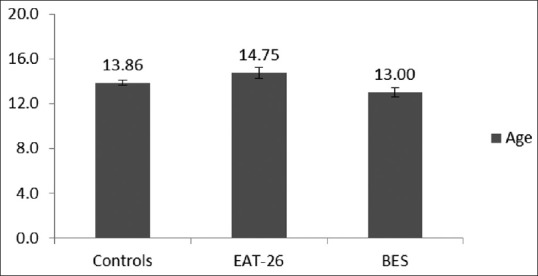

A significant variation (P < 0.05) was observed between the groups in relation to the age of onset of menstruation. High scorers of BES had an early onset compared to the controls, whereas the high scorers of EAT-26 reported a later onset than the controls [Figure 1]. When questioned about awareness regarding ED, we found that only 25.7% of the individuals interviewed were personally aware of the concept of ED. Among these “aware” individuals only 66.6% were faintly familiar with the physical manifestations of ED.

Figure 1.

Comparison between ages of onset of menstruation among the females of controls, eating attitudes test-26 high scorers and binge eating scale high scorers

DISCUSSION

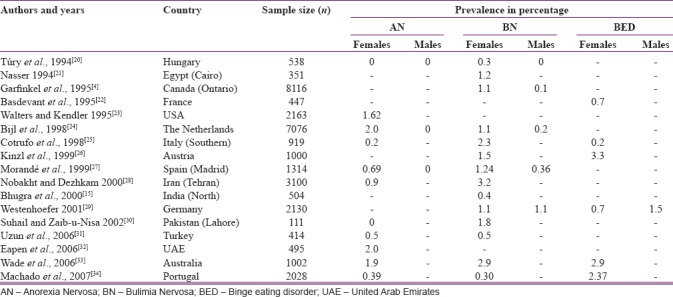

ED are among the most common psychological disorders affecting the youth of nations globally. Gard and Freeman stated that although ED were known to be very prevalent in upper-class societies or westernized communities, recent studies indicate that people from lower socio-economic status are equally prone to ED such as AN, BN and BED.[19] Thus many epidemiological studies on ED have been conducted worldwide with varying prevalence rates. Some noted studies are briefly listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Epidemiology of eating disorders in different countries

The prevalence values from our investigation are higher than the reports from other regions worldwide because further screening and criterion-based diagnosis of high scorers of both the questionnaires could not be conducted. The reason for this being the lack of expertise in the field of ED among Indian psychiatrists,[35] which in turn is due to low or nil reports or admission of patients with ED. Thus, the results in our study indicate the presence of eating distress and do not directly imply the presence of ED; however, the high scoring subjects of either questionnaire are definitely prone to suffer from an ED at least once in their lifetime. It has been stated by Golden et al., that as soon as an adolescent engages in extensive thinking about food consumption or restriction, body shape, weight, etc., or any extreme practices with weight loss as the main goal, a diagnosis of ED should be made.[36] The participants in the present study clearly exhibited such tendencies.

The overall excessive body weight seen in case of the high scorers of BES can be explained due to frequent binging episodes with the higher WHR implying abdominal obesity. On the other hand, lower weight in EAT-26 high scorers may be attributable to weight loss owing to varying degrees of calorie restriction.[37] Radical deviations from the normal BMI of an individual is one among the many characteristic features of any ED. Decreased BMI in high scorers of EAT-26 accord with the results from a study by Curatola et al., among AN patients.[38] Similarly, another analysis reported 22.2% of people with BED to be moderately obese (BMI >30) which corresponded with our study.[39]

Variations in the Hb levels of patients with AN have been reported earlier in different contexts by two groups of investigators. However, both their studies display contradicting results. While one observed low Hb content in people with AN,[40] the other reported normal Hb in AN which in turn tallied with our findings.[41] Although our study revealed many individual anemic students, they did not belong to a specific group.

It has earlier been stated that stress in any form could be a triggering factor in case of ED.[42] A large portion of the subjects who participated in this study were negatively affected by either physical or mental stress which could be the source for their eating distress. We also noticed obesity prevailing in the family of high scorers of BES. This has been already been dealt with in another study where one of their findings disclosed that the relatives of patients with BED presented with a greater incidence of obesity than the relatives of persons without BED, thus explaining the reason for our observation.[43] Diabetic conditions prevalent in the families of high scorers of BES could also be due to obesity.

Frisch and McArthur stated that for the inception of normal cyclical ovarian activity, a crucial and definitive weight or body fat content is an undisputable prerequisite.[44] From this, we can infer that the late onset of menstruation in case of EAT-26 high scorers is due to their low body weight owing to caloric restriction and low or nil consumption of fat rich food. Similarly, early onset of menstruation in BES high scorers is because of their obese nature as a result of high calorie and fat diet consumption during their binging episodes.

While evaluating the degree of awareness of ED among the participants, we arrived at an alarming discovery that a very small percentage of them had a vague idea of the concept of ED and fewer still knew about the general indicators of the disorders. Although a significant proportion of students in our investigation exhibited symptoms of eating distress, it appeared as if ED were seemingly unheard of, among the students of Mysore.

CONCLUSION

Many studies on the prevalence of ED have been conducted in different countries thus far. Yet, Indian studies are very limited in number or incomplete due to the lack of a benchmark diagnostic technique for psychiatrists to be employed on the Indian population for the detection of ED. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first, pilot investigation in the state of Karnataka. As a concluding remark, we can say that this investigation confirmed the definite existence of eating distress and in many ways hinted at the silent presence of ED in the student population of Mysore.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the research staff of Molecular Reproductive and Human Genetics Laboratory, Department of Studies in Zoology, University of Mysore for their guidance and technical support. We would also like to thank our team members Divyashree DS, Harshitha MP, Katyayini Aralikatti, Sowmya BN and Swathi UM for their contributions toward data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute of Mental Health. Eating Disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Institute of Mental Health. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moriarty CM, Harrison K. Television exposure and disordered eating among children: A longitudinal panel study. J Commun. 2008;58:361–81. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garfinkel PE, Lin E, Goering P, Spegg C, Goldbloom DS, Kennedy S, et al. Bulimia Nervosa in a Canadian community sample: Prevalence and comparison of subgroups. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1052–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinhausen HC, Winkler C, Meier M. Eating disorders in adolescence in a Swiss epidemiological study. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22:147–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199709)22:2<147::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szabo CP, Hollands C. Abnormal eating attitudes in secondary-school girls in South Africa – A preliminary study. S Afr Med J. 1997;87:524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hay P. The epidemiology of eating disorder behaviors: An Australian community-based survey. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23:371–82. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199805)23:4<371::aid-eat4>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preti A, Girolamo Gd, Vilagut G, Alonso J, Graaf Rd, Bruffaerts R, et al. The epidemiology of eating disorders in six European countries: Results of the ESEMeD-WMH project. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:1125–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jennings PS, Forbes D, McDermott B, Hulse G, Juniper S. Eating disorder attitudes and psychopathology in Caucasian Australian, Asian Australian and Thai University students. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:143–9. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mumford DB, Whitehouse AM, Platts M. Sociocultural correlates of eating disorders among Asian schoolgirls in Bradford. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:222–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.158.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mumford DB, Whitehouse AM, Choudry IY. Survey of eating disorders in English-medium schools in Lahore, Pakistan. Int J Eat Disord. 1992;11:173–84. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho TF, Tai BC, Lee EL, Cheng S, Liow PH. Prevalence and profile of females at risk of eating disorders in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2006;47:499–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mousa TY, Al-Domi HA, Mashal RH, Jibril MA. Eating disturbances among adolescent schoolgirls in Jordan. Appetite. 2010;54:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srinivasan TN, Suresh TR, Jayaram V, Fernandez MP. Eating disorders in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 1995;37:26–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhugra D, Bhui K, Gupta KR. Bulimic disorders and sociocentric values in North India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35:86–93. doi: 10.1007/s001270050012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silawat N, Rami AC. Comparative study of eating disorder between different zones of India in females players of basketball. Shodh Samiksha Aur Mulyankan Int Res J. 2009;2:829–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE. The eating attitudes test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med. 1982;12:871–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav. 1982;7:47–55. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gard MC, Freeman CP. The dismantling of a myth: A review of eating disorders and socioeconomic status. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;20:1–2. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199607)20:1<1::AID-EAT1>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Túry F, Günther R, Szabó P, Forgács A. Epidemiologic data on eating disorders in Hungary: Recent results. Orv Hetil. 1994;135:787–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasser M. Screening for abnormal eating attitudes in a population of Egyptian secondary school girls. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1994;29:25–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00796445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basdevant A, Pouillon M, Lahlou N, Le Barzic M, Brillant M, Guy-Grand B, et al. Prevalence of binge eating disorder in different populations of French women. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;18:309–15. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199512)18:4<309::aid-eat2260180403>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walters EE, Kendler KS. Anorexia nervosa and anorexic-like syndromes in a population-based female twin sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:64–71. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bijl RV, Ravelli A, van Zessen G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the general population: Results of the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:587–95. doi: 10.1007/s001270050098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cotrufo P, Barretta V, Monteleone P, Maj M. Full-syndrome, partial-syndrome and subclinical eating disorders: An epidemiological study of female students in Southern Italy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;98:112–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinzl JF, Traweger C, Trefalt E, Mangweth B, Biebl W. Binge eating disorder in females: A population-based investigation. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25:287–92. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199904)25:3<287::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morandé G, Celada J, Casas JJ. Prevalence of eating disorders in a Spanish school-age population. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24:212–9. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nobakht M, Dezhkam M. An epidemiological study of eating disorders in Iran. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28:265–71. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200011)28:3<265::aid-eat3>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westenhoefer J. Prevalence of eating disorders and weight control practices in Germany in 1990 and 1997. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;29:477–81. doi: 10.1002/eat.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suhail K, Zaib-u-Nisa Prevalence of eating disorders in Pakistan: Relationship with depression and body shape. Eat Weight Disord. 2002;7:131–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03354439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uzun O, Güleç N, Ozşahin A, Doruk A, Ozdemir B, Calişkan U, et al. Screening disordered eating attitudes and eating disorders in a sample of Turkish female college students. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47:123–6. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eapen V, Mabrouk AA, Bin-Othman S. Disordered eating attitudes and symptomatology among adolescent girls in the United Arab Emirates. Eat Behav. 2006;7:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wade TD, Bergin JL, Tiggemann M, Bulik CM, Fairburn CG. Prevalence and long-term course of lifetime eating disorders in an adult Australian twin cohort. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:121–8. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Machado PP, Machado BC, Gonçalves S, Hoek HW. The prevalence of eating disorders not otherwise specified. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:212–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.20358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malik SC. Postgraduate Psychiatry. In: Vyas JN, Ahuja N, editors. Eating disorders. New Delhi: B I Churchill Livingstone; 1992. p. 260.p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Golden NH, Katzman DK, Kreipe RE, Stevens SL, Sawyer SM, Rees J, et al. Eating disorders in adolescents: Position paper of the society for adolescent medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33:496–503. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huse DM, Lucas AR. Dietary patterns in anorexia nervosa. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;40:251–4. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/40.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curatola G, Camilloni MA, Vignini A, Nanetti L, Boscaro M, Mazzanti L, et al. Chemical-physical properties of lipoproteins in anorexia nervosa. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:747–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fairburn CG, Doll HA, Welch SL, Hay PJ, Davies BA, O’Connor ME, et al. Risk factors for binge eating disorder: A community-based, case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:425–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.5.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nova E, Lopez-Vidriero I, Varela P, Casas J, Marcos A. Evolution of serum biochemical indicators in anorexia nervosa patients: A 1-year follow-up study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2008;21:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2007.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lambert M, Hubert C, Depresseux G, Vande Berg B, Thissen JP, Nagant de Deuxchaisnes C, et al. Hematological changes in anorexia nervosa are correlated with total body fat mass depletion. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;21:329–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(1997)21:4<329::aid-eat4>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chadda R, Malhotra S, Asad AG, Bambery P. Socio-cultural factors in anorexia nervosa. Indian J Psychiatry. 1987;29:107–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hudson JI, Lalonde JK, Berry JM, Pindyck LJ, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, et al. Binge-eating disorder as a distinct familial phenotype in obese individuals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:313–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frisch RE, McArthur JW. Menstrual cycles: Fatness as a determinant of minimum weight for height necessary for their maintenance or onset. Science. 1974;185:949–51. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4155.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]