Abstract

Purpose

The misuse of inauthentic cell lines is widely recognized as a major threat to the integrity of biomedical science. Whereas the majority of efforts to address this have focused on DNA profiling, we sought to anatomically, transcriptionally, and functionally authenticate the RF/6A chorioretinal cell line, which is widely used as an endothelial cell line to model retinal and choroidal angiogenesis.

Methods

Multiple vials of RF/6A cells obtained from different commercial distributors were studied to validate their genetic, transcriptomic, anatomic, and functional fidelity to bona fide endothelial cells.

Results

Transcriptomic profiles of RF/6A cells obtained either de novo or from a public data repository did not correspond to endothelial gene expression signatures. Expression of established endothelial markers were very low or undetectable in RF/6A compared to primary human endothelial cells. Importantly, RF/6A cells also did not display functional characteristics of endothelial cells such as uptake of acetylated LDL, expression of E-selectin in response to TNF-α exposure, alignment in the direction of shear stress, and AKT and ERK1/2 phosphorylation following VEGFA stimulation.

Conclusions

Multiple independent sources of RF/6A do not exhibit key endothelial cell phenotypes. Therefore, these cells appear unsuitable as surrogates for choroidal or retinal endothelial cells. Further, cell line authentication methods should extend beyond genomic profiling to include anatomic, transcriptional, and functional assessments.

Keywords: RF/6A, cell culture, endothelial

The vessels of the choroid and retina nourish the outer and inner retina, respectively. Dysfunction, aberrant growth, and involution of the endothelial cells lining these vessels are of critical importance to diverse ophthalmic conditions, including the most common causes of untreatable blindness, namely choroidal neovascularization in neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD),1 choroidal involution in atrophic AMD,2 and retinal vessel proliferation in proliferative diabetic retinopathy and leakage in diabetic macular edema (DME).3 Collectively, chorioretinal vascular instability affects the vision of over 56 million people worldwide.4,5 As evidence of the broad recognition of their role in human vision diseases, numerous cell-based models have been adopted to further understanding of the physiology and pathophysiology of choroidal and retinal endothelial cells.

RF/6A cells, described in the literature as “chorioretinal endothelial cells,” are among the most prevalent in vitro choroidal and retinal endothelial cell model employed in the literature. Originally isolated in 1968 from a crude choroid-retina preparation of a rhesus macaque fetus in mid-gestation, these spontaneously transformed cells were established as endothelial cells by virtue of their cobblestone morphology, positivity for von Willebrand factor (VWF), and presence of Weibel-Palade bodies (WPB), an endothelial-specific organelle.6 The investigators that established this cell line reported that after over 500 passages, VWF expression was reduced or absent, but that these cells retained WPB and morphological characteristics of endothelial cells. Since that time, RF/6A have been widely adopted to model angiogenesis, cell differentiation, and responses to various drug and environmental treatments in the choroid and retina.

Despite their widespread use, a rigorous and contemporary characterization of the endothelial cell properties of RF/6A cells has not been reported. Here, we report that commercially distributed RF/6A cells lack essentially all classic endothelial cell markers and numerous functional behaviors. These findings assume broad importance for the research community that utilizes RF/6A cells to model the vascular biology and pathology of the choroid and retina.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Reagents

All cells were maintained in a sterile humidified incubator at 37°C in 5% atmospheric CO2. We used RF/6A purchased on four separate occasions (Table 1). RF/6A-1 and -3 were cultivated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media (as in Ref. 7). RF/6A-2 were cultivated in Eagle's modified essential media, as recommended by ATCC. RF/6A-4 were cultivated in RPMI 1640 as recommended by RIKEN BRC (Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan). All basal media formulations were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 U/mL streptomycin. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and primary mouse microvascular retinal endothelial cells (mRECs; isolated from C57BL/6) were purchased from Lonza (Allendale, NJ, USA) and Cell Biologics (Chicago, IL, USA), respectively, and grown on gelatin coated plastic dishes in Vascular Cell Basal Medium supplemented with the Endothelial Cell Growth Kit-VEGF (EGM; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Primary human microvascular retinal endothelial cells (HRECs) were purchased from Cell Systems (Kirkland, WA, USA), grown on plastic dishes coated with Attachment Factor in Complete Classic Medium Kit with Serum as recommended by the manufacturer. Primary cells were used at or below passage 7. Cells were stimulated with recombinant human TNF-α (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) and recombinant human VEGFA-165 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

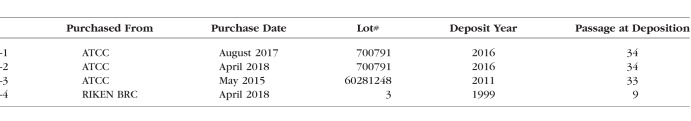

Table 1.

Details of RF/6A Cells Used in This Study

RNA Isolation, Library Construction, and Sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from RF/6A using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's specifications. RNA quality was confirmed by Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Library construction and sequencing (50-bp single-end) were performed by BGI on a BGISEQ-500 sequencing platform. Raw sequencing data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus at accession GSE113674. Reads were assessed for quality using FastQC (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastq_screen/). Transcript abundance was quantified using Salmon8 followed by importing and summarizing transcript abundances to the gene level as previously described.9 The DESeq2 Bioconductor package10 in the R statistical computing environment11 was used for normalizing count data, performing exploratory data analysis including principal components analysis clustering, estimating dispersion, and fitting a negative binomial model for each gene to assess genes for differential expression. After obtaining a list of differentially expressed genes, log fold changes, and P values, the Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate procedure was used to correct P values for multiple testing.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR Analysis

For HUVEC, HREC, RF/6A-1, -2, and -3, total RNA was collected using the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and DNase treated and reverse transcribed using QuantiTect (Qiagen). For RF/6A-4, RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), and reverse transcribed using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover (TOYOBO, Kita-ku, Osaka, Japan). Diluted cDNA was amplified by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The qPCR cycling conditions were 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of a two-step amplification program (95°C for 15 seconds and 58°C for 1 minute). Relative expression of target genes was determined by the 2−ΔΔCt method. cDNA from unstimulated HUVEC was used to calculate PCR efficiency for CDH5 and VWF primers, and cDNA from TNF-α-stimulated HUVEC and RF/6A were used to calculate PCR efficiency of E-selectin and PECAM1 primer sets. Oligonucleotide primers sequences are described in Table 2.

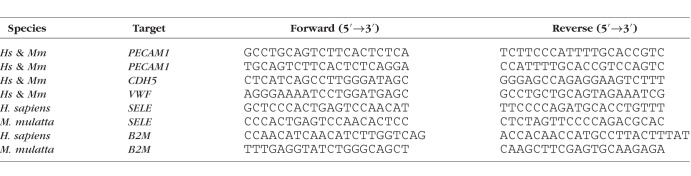

Table 2.

qPCR Primer Sequences Used in This Study

Western Blotting

Cells were homogenized in either Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Thermo Fisher) supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture (Pierce), or directly in 1× Laemmli buffer (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA, USA) supplemented with β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Protein concentrations of RIPA lysates were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Thermo Fisher) with BSA as a standard. Proteins (20–40 μg) were separated on a run on 4-20% polyacrylamide Tris-glycine gels (Thermo Fisher) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The transferred membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) and incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies against: human and rhesus PECAM1 (1:500; JC/70A, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), human and mouse VE-cadherin (1:200, C-19, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), phospho-AKT (Ser473) (1:1000, 12694S, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (1:1000, 4370, Cell Signaling), α-tubulin (1:5000, ab89984, Abcam), Vinculin (1:1000, V4139, Sigma), and β-actin (1:1000, ab13822, Abcam). The signals were visualized with an Odyssey imaging system.

Immunofluorescent Cell Labeling

Cells plated on gelatin-coated glass slides (Nunc Lab-Tek II Chamber Slide System) were allowed to attach overnight. Cells were fixed for 20 minutes in 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA), then incubated in blocking solution consisting of 2% normal donkey serum, 1% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.05% Tween 20, 0.05% sodium azide in 1× PBS (w/o Ca2+/Mg2+), pH 7.2 for 30 minutes, followed by 30-minute blocking in Protein Block, Serum-free (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) + 0.1% Triton X-100. Sheep anti-Rab27a (Thermo Fisher) or an equivalent concentration of sheep IgG (Thermo Fisher) was diluted 1:40 in donkey serum blocking solution for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-sheep IgG (Thermo Fisher). Cells were mounted in ProLong Gold Antifade with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Thermo Fisher) and visualized on an inverted Nikon A1R fluorescent microscope. Identical imaging parameters (objective, light intensity, gain, exposure) were used between slides and samples.

Immunohistochemistry

Five micrometers paraffin sections from formalin fixed eyes of Macaca fascicularis were deparaffinized, hydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval by trypsin digestion. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-PECAM1 (JC/70A, Abcam) diluted 1:50 in Antibody Diluent (Dako). Antibody staining was visualized using a streptavidin conjugated anti-mouse, VECTASTAIN ABC-AP Kit, and VECTOR Blue Alkaline Phosphatase Substrate Kit (all from Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Acetylated LDL-Uptake

After an overnight incubation in serum-free medium, 10 μg/mL DiI Acetylated LDL (L3484, Thermo Fisher) was added to the culture medium for 4 to 16 hours. Live cells were washed in PBS and visualized using a Nikon A1R fluorescent microscope.

Shear Stress Stimulation and Nuclear Alignment Analysis

Cells were seeded into tissue culture-treated 0.4 mm height flow chambers (Ibidi, Fitchburg, WI, USA) and allowed to reach confluence for 3 days. Cells were stimulated with shear stress (5 dyne/cm2) for 48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2 by perfusing complete cell culture media with a peristaltic pump and an inline pulse dampener. Control cells were maintained in static (no flow) conditions. Following stimulation, cells were gently washed in PBS, fixed in 4% PFA, incubated with Acti-stain 488 phalloidin (Cytoskeleton, Inc., Denver, CO, USA). Slides were filled with ProLong Gold Antifade with DAPI (Thermo Fisher) and visualized on an inverted Nikon A1R fluorescent microscope. Binarized nuclear images were analyzed using the ImageJ ellipse function to quantify the orientation of the nuclear long axis relative to the flow direction. A total of 3500 to 5600 nuclei were analyzed per condition.

Results

Transcriptomic Profiling of RF/6A Cells

Using FastQ screening of high-throughput RNA sequencing, we confirmed that RF/6A-1 cells were of M. mulatta origin, with >95% of reads mapping to the rhesus macaque genome, of which 22.15% mapped uniquely to the M. mulatta genome, compared to human (0.29%), rat, mouse, drosophila, chicken, Escherichia coli, PhiX (all 0%). Next, we sought to determine whether the RF/6A transcriptome was consistent with that of endothelial cells. As a positive control for bona fide endothelial cell transcriptomes, we analyzed publically deposited RNAseq libraries of HUVECs from a separate laboratory and study.12 As additional positive controls, we analyzed two separate publically deposited RNAseq libraries of HRECs.13,14 In addition to our own RNAseq study, we also analyzed transcriptomic libraries of unstimulated RF/6A cells deposited into a public database by a separate laboratory from an independent study.7

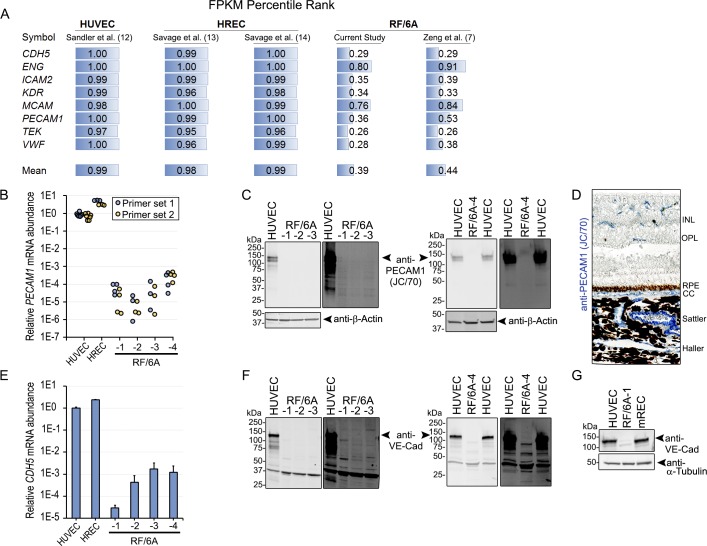

We evaluated abundance of individual genes that are established as being enriched in endothelial cells (CDH5, ENG, ICAM2, KDR, MCAM, PECAM1, TEK, and VWF). As assessed by fragments per kilobase of exon model (FPKM) rank, abundance of these transcripts was enriched to a far greater extent in HUVEC12 (mean 99%ile), HREC13,14 (mean 98%ile and 99%ile, respectively) than in the RF/6A-1 cells of our study (39%ile) or in RF/6A from an independent study7 (44%ile) (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Average percentile rank of common endothelial cell-enriched genes. 1.00 refers to genes expressed approaching the 100th percentile compared to all mapped genes in the sample. (B) PECAM1 mRNA abundance by qPCR using two independent primer sets that amplify homologous regions of human and rhesus mRNAs. Normalized to B2M. (C) Immunoblotting for PECAM1 in HUVEC and RF/6A. Low (left) and high (right) exposures shown. (D) Immunohistochemistry of M. fascicularis eye with the JC/70A PECAM1 antibody. Reaction product is blue. (E) Abundance of CDH5 mRNA, which encodes for VE-Cadherin (VE-Cad), by qPCR using primers that amplify a homologous region of human and rhesus mRNAs. Normalized to B2M. (F) Immunoblotting of VE-Cad in HUVEC and RF/6A. Low (left) and high (right) exposures shown. (G) VE-Cad immunoblotting of HUVEC, RF/6A-1, and mREC. INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; RPE, retinal pigmented epithelium; CC, choriocapillaris; Sattler, Sattler's layer; Haller, Haller's layer.

To confirm these RNAseq findings, we designed two primer pairs that amplify sequences of PECAM1 mRNA that share perfect homology between human and rhesus macaque. PECAM1 mRNA abundance was 1988- to 120,323-fold lower in RF/6A from four sources compared to HUVEC and 11,326- to 685,439-fold lower compared to HREC (Fig. 1B). We next used an antibody that recognizes PECAM1 of both human and nonhuman primate origin (JC/70A, Abcam). Western blotting of HUVEC lysates exhibited strong expression of PECAM1 (Fig. 1C). Conversely, no band was detected in RF/6A lysates from any of four sources (Fig. 1C). We confirmed that nonhuman primate endothelium of the choroid and retina express PECAM1 by immunolabeling sections from M. fascicularis (which shares 100% homology with M. mulatta) with the same antibody (Fig. 1D).

We also investigated the expression of vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-Cad; encoded by the gene CDH5), which is robustly expressed in normal human choroidal endothelium.15 In consonance with RNA-seq data, qPCR using a primer pair that recognizes a conserved region of human and macaque CDH5, which encodes VE-Cad, resulted in undetectable or and at least 590-fold lower CDH5 mRNA in RF/6A cells than in HUVEC and 1424-fold lower than HREC (Fig. 1E). Consistent with the lack of robust CDH5 mRNA expression, VE-Cad protein was undetectable by immunoblotting in any of four RF/6A cell lines (Fig. 1F). We confirmed that the antibody (sc-6458, C-19, Santa Cruz) was capable of detecting evolutionarily conserved portions of the VE-Cad protein by immunoblotting human and mouse endothelial cells (Fig. 1G). Collectively, we interpret these findings to indicate that RF/6A do not resemble choroidal and retinal endothelial cells with respect to expression of endothelial-specific genes.

WPB in RF/6A Cells

When first described, the endothelial cell origin of RF/6A was ascribed to the presence of WPB, an endothelial cell-specific regulated secretory organelle that functions in the storage and secretion of VWF, P-selectin,16 tissue plasminogen activator,17 and interleukin-8.18 Ultrastructural analysis of developing19 and pathological20 choroidal vessels demonstrate WPB present within the choroidal endothelium of humans. In rhesus monkeys, WPB are reported in retinal vessels21 and in choroidal vessels in experimental laser-induced choroidal neovascularization.22 Primary and immortalized human choroidal endothelial cells are also reported to be VWF positive.23,24 Thus, bona fide choroidal and retinal endothelial cells would be expected to contain WPB.

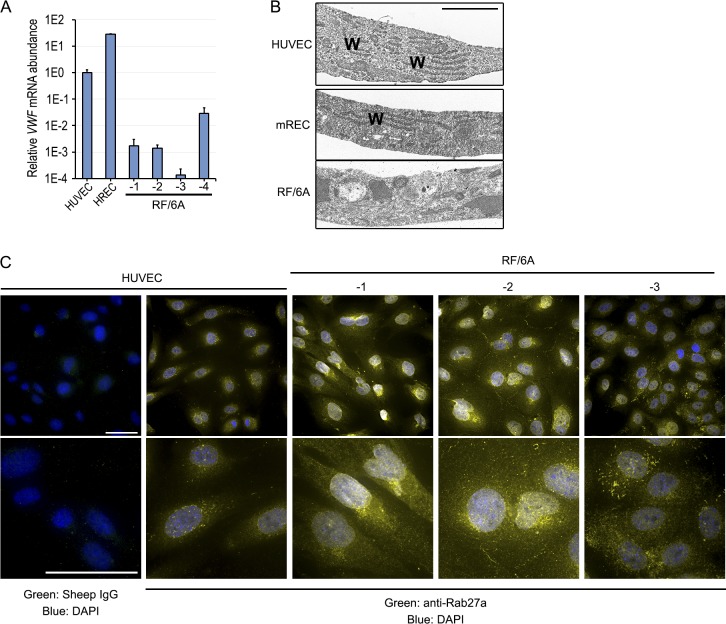

VWF is both necessary and sufficient for formation of WPB. Indeed, the microstructure of WBP is composed of VWF helices and tubules.25 In the original description of these cells,6 RF/6A cells were reported to retain WPB even at later passages despite losing VWF expression. qPCR analysis of VWF mRNA confirmed RNA-seq data that expression in RF/6A cells was relatively low (Fig. 2A). In RF/6A-1-3, VWF mRNA was 572- to 7441-fold lower than HUVEC and 16,257- to 211,382-fold lower than HREC. Interestingly, VWF mRNA was relatively higher in RF/6A-4, but still ∼34-fold lower than HUVEC and 971-fold lower than HREC. We next performed transmission electron microscopy to visualize WPB. Whereas WPB were readily detected in HUVEC and mREC, these structures were absent in RF/6A-1 cells (Fig. 2B). As a complementary approach to visualizing WPB, we performed immunofluorescent labeling of the GTPase Rab27a, which localizes to mature WPB,26–28 using an antibody that recognizes human, mouse, and rat homologs (PA5-47907, Thermo Fisher). Small, rod-shaped, Rab27a-positive organelles consistent with WPB were readily observed in HUVEC (Fig. 2C). Conversely, WBP-like structures were undetectable in both RF/6A-1 and -2 cells, where Rab27a staining was diffuse, consistent with staining observed in nonendothelial cells in other studies.26 In RF/6A-3 cells, approximately 25% of cells exhibited Rab27a staining consistent with WPB, suggesting that the complete loss of this endothelial cell-specific characteristic may have occurred relatively recently. Collectively, we interpret these findings to indicate that commercially distributed RF/6A cells do not robustly express VWF and are not identifiable as endothelial cells on the basis of the presence of WPB.

Figure 2.

(A) qPCR analysis of VWF mRNA in HUVEC, HREC, and RF/6A using primers that amplify homologous regions of human and rhesus mRNAs. (B) Transmission electron micrographs of HUVEC, mREC, and RF/6A-1. WPB are long rod-like structures, denoted by “W.” Scale bar = 2 μm. (C) Low (top) and high (bottom) magnification images of immunofluorescent staining for Rab27a in HUVEC, and RF/6A cells. Note rod-like structures corresponding to WPB in HUVEC, which are absent in RF/6A-1 and -2, and sporadic in RF/6A-3. Scale bar in low magnification = 50 μm, in high magnification = 10 μm.

Functional Endothelial Cell Assays in RF/6A Cells

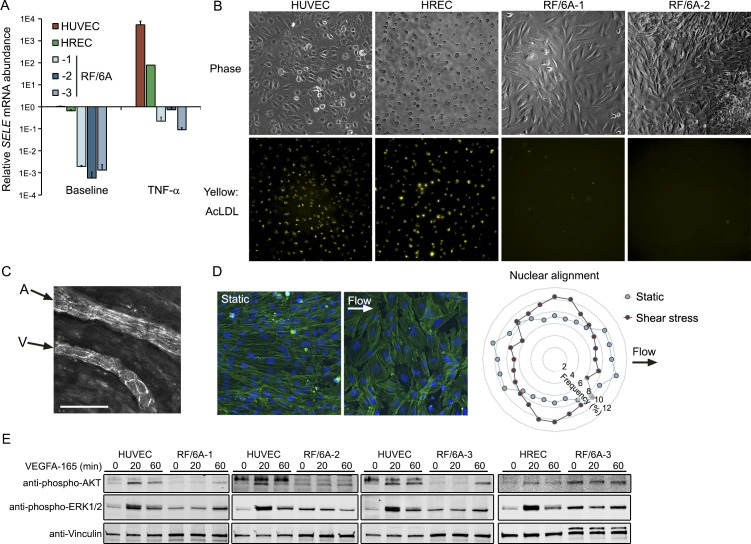

We sought to determine whether RF/6A cells exhibited characteristic endothelial cell behaviors. Recruitment and trafficking of leukocytes to areas of inflammation are critical functions of the endothelium, which is accomplished by expression of a cadre of surface receptors. We analyzed the relative expression of the endothelial-specific protein E-selectin (encoded by SELE) both basally and in response to TNF-α stimulation in comparison to HUVEC. Under basal conditions, RF/6A-1, -2, and -3 expressed 507-, 1697-, and 748-fold less SELE respectively compared to HUVEC and 336-, 1125-, and 496-fold less than HREC (Fig. 3A). Following stimulation with recombinant human TNF-α (50 ng/mL, 4 hours), which is biologically active in human and nonhuman primate, SELE expression was 7130- to 57,994-fold greater in HUVEC and 107- to 870-fold greater in HREC than in RF/6A cells. TNF-α-stimulation of RF/6A cells resulted in less SELE than the levels measured in unstimulated HUVEC and HREC. We interpret these findings to mean that RF/6A cells are not a suitable model to study TNF-α-stimulated endothelial inflammation.

Figure 3.

(A) qPCR analysis of SELE mRNA 4 hours after treatment with human TNF-α at 50 ng/mL. SELE primers amplify a region conserved between human and macaque. Normalized to B2M. (B) Representative phase (top) and DiI (bottom) images of HUVEC, HREC, and RF/6A after treatment with DiI-labeled acetylated LDL. (C) Arteriole/venule pair in Sattler's layer of a normal human eye labeled with PECAM1 to outline cell junctions. Arrows indicate flow direction. (D) Fluorescent micrographs of RF/6A under static (no flow) and shear stress conditions labeled with phalloidin and DAPI. Nuclear orientation was quantified with respect to the flow direction. (E) Immunoblotting of AKT and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in HUVEC, HREC, and RF/6A cells after VEGF-A stimulation for indicated durations.

Another long established functional behavior of endothelial cells, including an immortalized human choroidal endothelial cell line,24 is uptake and metabolism of acetylated low density lipoprotein (ac-LDL).29 Primary HUVEC and HREC exhibited robust ac-LDL uptake. Conversely, RF/6A-1 and -2 cells failed to accumulate ac-LDL in detectable levels (Fig. 3B). We interpret this finding to mean that RF/6A also lack this characteristic endothelial cell behavior.

Alignment in the direction of blood flow is another widely conserved property of endothelial cells. Like most of the vascular tree, human choroidal endothelium aligns parallel to the direction of shear stress in situ (Fig. 3C). Shear stress-induced cell alignment is governed by a mechanosensory complex consisting of PECAM1, VE-cadherin, and VEGF-R2, none of which is robustly expressed in RF/6A (Fig. 1A). Consistent with the lack of mechanosensory constituents, shear stress stimulation did not induce RF/6A-1 alignment in the direction of shear stress. Rather, we observed a modest but statistically significant realignment of cells perpendicular to the direction of shear stress (Fig. 3D), a phenotype reported in vascular smooth muscle cells,30,31 and fibroblasts.32,33 We interpret this finding to mean that RF/6A are not a suitable model to study endothelial-specific responses to fluid shear stress.

Finally, we next sought to clarify the extent to which RF/6A responded to VEGF stimulation by investigating signaling intermediates that are activated by VEGF in endothelial cells. Whereas treatment with recombinant human VEGFA-165, which shares 100% identity with M. malatta VEGFA, induced rapid and robust phosphorylation of AKT and ERK1/2 in HUVEC, RF/6A-1, -2, and -3 cells exhibited delayed and diminished phosphorylation of these signaling constituents (Fig. 3E). The relative biochemical insensitivity of RF/6A cells to VEGF-A is consistent with the relatively low expression of canonical VEGFA receptors (VEGF-R1, R2, NRP1, and NRP2) observed in RF/6A by RNAseq. We interpret these findings to mean that RF/6A cells are not a robust model in which to assess VEGFA stimulation of endothelial cells.

Discussion

This study provides the first rigorous analysis of the endothelial cell characteristics of the RF/6A cell line. One metric by which the suitability of an experimental tool can be judged is whether it possesses “face validity,” or similarity to the condition it seeks to model. The RF/6A line does not express an identifiable endothelial cell transcriptome, express established endothelial cell markers, or possess morphological characteristics of choroidal and retinal endothelial cells. Given the recognized heterogeneity of endothelial cells throughout the vascular tree (reviewed in Ref. 34), it bears mentioning that choroidal and retinal endothelial cells in culture or in situ possess each of these traits as demonstrated either in the literature or by the experiments herein. Thus, it is not simply the case that RF/6A cells do not exhibit these features because they reflect unique properties of “chorioretinal” endothelial cells.

A second criterion upon which to judge a model is “target validity,” or the ability to reproduce the effects of targets of inquiry or stimuli in the real system. RF/6A cells do not respond to diverse stimuli—shear stress, TNF-α, or VEGFA—in a manner consistent with endothelial cells. VEGFA-induced effects on choroidal and retinal endothelial cells underlies blinding conditions in millions of individuals. Therefore, it is particularly damning that RF/6A cells lack robust expression of canonical VEGF receptors at levels near that of bona fide endothelial cells, and that RF/6A cells are relatively insensitive to this stimulus. Thus, the RF/6A cell line also fails the target validity criteria.

Aside from VWF positivity, no quantitative characterization of this cell line has been published with respect to endothelial gene expression and characteristic behaviors. Presumably, these features were present in the founding cell(s) and have been lost over successive passages. Although the causes and kinetics of this loss of endothelial characteristics are unclear, one potential cause of loss of VWF reactivity is that VWF antagonizes endothelial proliferation.35 Over time, the RF/6A line may have drifted toward low VWF-expressing, rapidly dividing cells. These findings do not exclude the possibility that under certain culturing conditions such as confluency, media composition, and exogenous extracellular matrix, RF/6A never adopt EC characteristics. However, we interpret the data acquired from RF/6A cells from four batches, two suppliers, cultured in three distinct media formulations to suggest that the lack of endothelial characteristics in contemporary commercially available RF/6A is robust.

Numerous studies have employed RF/6A in capillary tube formation assays to assess the angiogenic potential of experimental compounds, drugs, and signaling intermediates. Importantly, capillary tube formation is not an endothelial cell-specific property; multiple nonendothelial cell types exhibit the capacity to form capillary like networks when plated on 3-D basement membrane, including primary human fibroblasts,36 breast,36–38 prostate,36 melanoma,38,39 glioblastoma,36,38,40 and bladder cancer cell lines,41 and macrophages from multiple myeloma patients.42 Thus, findings from tube formation assays of RF/6A cells to glean insights into the behavior of actual endothelial cells should be interpreted with caution.

Cell line misidentification and contamination are widely considered major threats to scientific rigor and confidence.43,44 In response, publishing and grant administering institutions have established new guidelines and requirements to safeguard against these errors. Cell line authentication best practices focus on establishing the species and genetic homogeneity of the line. In 1999, Dirks and colleagues41 used DNA fingerprinting to establish that ECV304, a widely used “endothelial” cell line, was in fact a subclone of T24 bladder carcinoma cells. This finding was made in the context of a cell line that was known at the time to deviate from fundamental endothelial cell characteristics, including the absence of expression of PECAM1 and VWF, and inability to stimulate E-selectin expression.45 Regrettably, the now 19-year-old revelation that ECV304 line is not endothelial has not eradicated its use in the literature as a model of endothelium in 2018.

Unlike ECV304/T24 cells, the RF/6A line would likely pass muster if the best practices recommended of cell line providers (ATCC), journal editors, and the National Institutes of Health were followed—the species of origin was uniquely identified as being of rhesus macaque origin, free from human or mouse cell line contaminants. The present findings in RF/6A cells suggest that confirming the genetic identity of a cell line is a necessary but not a sufficient step toward establishing the identity and utility of a cellular model. We strongly encourage investigators to quantify the validity of cell lines by transcriptional profiling and in relevant functional assays.

The use of better-characterized choroidal and retinal endothelial cells should supplant the use of RF/6A cells in the future. We caution laboratories against the use of RF/6A cells as an experimental model of endothelial cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank G. Pattison, E. Ghias, K. Langberg, D. Robertson, X. Zhou, K. Atwood, E. Dinning, L. Pandya, P. Shukla, D. Shultz, and A. Uittenbogaard for their technical assistance.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01EY028027 and American Heart Association (13SDG16770008) (BDG); JA was supported by NIH grants (DP1GM114862, R01EY022238, R01EY024068, and R01EY028027), John Templeton Foundation Grant 60763, and DuPont Guerry, III, Professorship; NK by NIH (K99EY024336, R00EY024336) and Beckman Initiative for Macular Research (BIMR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosure: R.D. Makin, None; I. Apicella, None; Y. Nagasaka, None; H. Kaneko, None; S.D. Turner, None; N. Kerur, P; J. Ambati, iVeena (I), Inflammasome Therapeutics (I), Allergan (C, R), Biogen (C), Boehringer-Ingelheim (C), Janssen (C), Olix Pharmaceuticals (C, R), Saksin LifeSciences (C), P; B.D. Gelfand, None

References

- 1.Ambati J, Atkinson JP, Gelfand BD. Immunology of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:438–451. doi: 10.1038/nri3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelfand BD, Ambati J. A revised hemodynamic theory of age-related macular degeneration. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22:656–670. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy S, Kern TS, Song B, Stuebe C. Mechanistic insights into pathological changes in the diabetic retina: implications for targeting diabetic retinopathy. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong WL, Su X, Li X, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e106–e116. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:556–564. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lou DA, Hu FN. Specific antigen and organelle expression of a long-term rhesus endothelial cell line. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1987;23:75–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02623586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng S, Whitmore SS, Sohn EH, et al. Molecular response of chorioretinal endothelial cells to complement injury: implications for macular degeneration. J Pathol. 2016;238:446–456. doi: 10.1002/path.4669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods. 2017;14:417–419. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soneson C, Love MI, Robinson MD. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Res. 2015;4:1521. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7563.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing;; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandler VM, Lis R, Liu Y, et al. Reprogramming human endothelial cells to haematopoietic cells requires vascular induction. Nature. 2014;511:312–318. doi: 10.1038/nature13547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savage SR, Bretz CA, Penn JS. RNA-Seq reveals a role for NFAT-signaling in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells treated with TNFalpha. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savage SR, McCollum GW, Yang R, Penn JS. RNA-seq identifies a role for the PPARbeta/delta inverse agonist GSK0660 in the regulation of TNFalpha-induced cytokine signaling in retinal endothelial cells. Mol Vis. 2015;21:568–576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schubert C, Pryds A, Zeng S, et al. Cadherin 5 is regulated by corticosteroids and associated with central serous chorioretinopathy. Hum Mutat. 2014;35:859–867. doi: 10.1002/humu.22551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonfanti R, Furie BC, Furie B, Wagner DD. PADGEM. (GMP140) is a component of Weibel-Palade bodies of human endothelial cells. Blood. 1989;73:1109–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosnoblet C, Vischer UM, Gerard RD, et al. Storage of tissue-type plasminogen activator in Weibel-Palade bodies of human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1796–1803. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.7.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Utgaard JO, Jahnsen FL, Bakka A, Brandtzaeg P, Haraldsen G. Rapid secretion of prestored interleukin 8 from Weibel-Palade bodies of microvascular endothelial cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1751–1756. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koina ME, Baxter L, Adamson SJ, et al. Evidence for lymphatics in the developing and adult human choroid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:1310–1327. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abri A, Binder S, Pavelka M, Tittl M, Neumuller J. Choroidal neovascularization in a child with traumatic choroidal rupture: clinical and ultrastructural findings. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;34:460–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schraermeyer U, Julien S. Effects of bevacizumab in retina and choroid after intravitreal injection into monkey eyes. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013;13:157–167. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.748741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Archer DB, Gardiner TA. Electron microscopic features of experimental choroidal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;91:433–457. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(81)90230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Browning AC, Gray T, Amoaku WM. Isolation, culture, and characterisation of human macular inner choroidal microvascular endothelial cells. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1343–1347. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.063602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loeven MA, van Gemst JJ, Schophuizen CMS, et al. A novel choroidal endothelial cell line has a decreased affinity for the age-related macular degeneration-associated complement factor H variant 402H. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:722–730. doi: 10.1167/iovs.IOVS-17-22893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berriman JA, Li S, Hewlett LJ, et al. Structural organization of Weibel-Palade bodies revealed by cryo-EM of vitrified endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17407–17412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902977106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hannah MJ, Hume AN, Arribas M, et al. Weibel-Palade bodies recruit Rab27 by a content-driven, maturation-dependent mechanism that is independent of cell type. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3939–3948. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nightingale TD, Pattni K, Hume AN, Seabra MC, Cutler DF. Rab27a and MyRIP regulate the amount and multimeric state of VWF released from endothelial cells. Blood. 2009;113:5010–5018. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-181206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zografou S, Basagiannis D, Papafotika A, et al. A complete Rab screening reveals novel insights in Weibel-Palade body exocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:4780–4790. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craig LE, Spelman JP, Strandberg JD, Zink MC. Endothelial cells from diverse tissues exhibit differences in growth and morphology. Microvasc Res. 1998;55:65–76. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1997.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu SQ, Goldman J. Role of blood shear stress in the regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell migration. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2001;48:474–483. doi: 10.1109/10.915714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee AA, Graham DA, Dela Cruz S, Ratcliffe A, Karlon WJ. Fluid shear stress-induced alignment of cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biomech Eng. 2002;124:37–43. doi: 10.1115/1.1427697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng CP, Swartz MA. Fibroblast alignment under interstitial fluid flow using a novel 3-D tissue culture model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1771–H1777. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01008.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng CP, Hinz B, Swartz MA. Interstitial fluid flow induces myofibroblast differentiation and collagen alignment in vitro. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4731–4739. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Augustin HG, Koh GY. Organotypic vasculature: from descriptive heterogeneity to functional pathophysiology. Science. 2017;357:eaal2379. doi: 10.1126/science.aal2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starke RD, Ferraro F, Paschalaki KE, et al. Endothelial von Willebrand factor regulates angiogenesis. Blood. 2011;117:1071–1080. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-264507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donovan D, Brown NJ, Bishop ET, Lewis CE. Comparison of three in vitro human 'angiogenesis' assays with capillaries formed in vivo. Angiogenesis. 2001;4:113–121. doi: 10.1023/a:1012218401036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Basu GD, Liang WS, Stephan DA, et al. A novel role for cyclooxygenase-2 in regulating vascular channel formation by human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R69. doi: 10.1186/bcr1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Francescone RA, III, Faibish M, Shao R. A. Matrigel-based tube formation assay to assess the vasculogenic activity of tumor cells. J Vis Exp. 2011;55:3040. doi: 10.3791/3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maniotis AJ, Folberg R, Hess A, et al. Vascular channel formation by human melanoma cells in vivo and in vitro: vasculogenic mimicry. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:739–752. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65173-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El Hallani S, Boisselier B, Peglion F, et al. A new alternative mechanism in glioblastoma vascularization: tubular vasculogenic mimicry. Brain. 2010;133:973–982. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dirks WG, MacLeod RA, Drexler HG. ECV304 (endothelial) is really T24 (bladder carcinoma): cell line cross- contamination at source. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1999;35:558–559. doi: 10.1007/s11626-999-0091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scavelli C, Nico B, Cirulli T, et al. Vasculogenic mimicry by bone marrow macrophages in patients with multiple myeloma. Oncogene. 2008;27:663–674. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chatterjee R. Cell biology. Cases of mistaken identity. Science. 2007;315:928–931. doi: 10.1126/science.315.5814.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stacey GN. Cell contamination leads to inaccurate data: we must take action now. Nature. 2000;403:356. doi: 10.1038/35000394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hughes SE. Functional characterization of the spontaneously transformed human umbilical vein endothelial cell line ECV304: use in an in vitro model of angiogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 1996;225:171–185. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]