Abstract

Background:

Integrating primary care and behavioral health is an important focus of health system transformation.

Method:

Cross-case comparative analysis of 19 practices in the U.S. describing integrated care clinical workflows. Surveys, observation visits, and key informant interviews analyzed using immersion-crystallization.

Results:

Staff performed tasks and behaviors – guided by protocols or scripts – to support four workflow phases: (1) Identifying; (2) Engaging/transitioning; (3) Providing treatment; and (4) Monitoring/adjusting care. Shared electronic health records (EHR) and accessible staffing/scheduling facilitated workflows.

Conclusion:

Stakeholders should consider these workflow phases, address structural features, and utilize a developmental approach as they operationalize integrated care delivery.

Keywords: behavioral medicine, primary care, mental health, practice management, medical home / patient-centered medical home, qualitative research / study, longitudinal, case study

INTRODUCTION

Integration of primary and behavioral health care embodies triple aim objectives of better care, better quality, and controlled costs1 and is an important focus of local, regional, and national health system transformation efforts.2–6 We define integrated care as a practicing team of primary care and behavioral health clinicians (BHCs), working together with patients and families, to address the spectrum of behavioral health concerns that present in primary care, including mental health disorders as well as psychosocial factors associated with physical health, at-risk behaviors, or health behavior change (e.g., smoking, diet).7, 8 A growing number of resources describe integrated care and how to implement it.7, 9–13 Nevertheless, practices still find it challenging to translate their vision for integration into clinical reality.14

Prior work by our team has described critical dimensions of how integrated care is delivered across diverse settings based on two studies, Advancing Care Together (ACT) and the Integration Workforce Study (IWS).13, 15–26 For example, Cohen and colleagues identified five organizing constructs that interact with practice context to influence the integration of primary care and behavioral health, ranging from identifying the target population through understanding stakeholder’s mental models.13 Additionally, Gunn and colleagues described how physical layout impacts team interactions in integrated settings.23 Although prior ACT and IWS publications describe aspects related to the delivery of integrated care,13, 20, 21 this work does not provide insight into how integrated care workflows are operationalized.

Therefore, in this study we examine and identify how a group of diverse, real-world practices operationalize clinical workflows to support delivery of integrated care. We define clinical workflows as a process involving a series of tasks performed by various people within and between work environments to deliver care. Accomplishing each task may require actions by one person, between people, or across organizations – and can occur sequentially or simultaneously.4 Further, we identify contextual factors that could facilitate or impede the tasks and behaviors associated with these workflows and provide citations to ACT/IWS manuscripts that describe specific factors in greater detail. We anticipate that findings may help researchers, end users (e.g., health system leaders, primary care clinicians, BHCs), and policy makers conceptualize and address barriers as they redesign practice to operationalize integrated care delivery.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

We studied 19 practices in the United States; 11 practices were participating in Advancing Care Together (ACT) and 8 practices were from the Integration Workforce Study (IWS). Both ACT and IWS focused on understanding implementation of integrated care. ACT was a three year longitudinal study of practices in Colorado implementing integrated care, most sites were in the early stages of integration.13, 21 IWS was a cross sectional study of sites across the United States identified as experienced in delivering integrated care.12 These studies and data collection strategies are described in detail elsewhere13, 19–21 and summarized below. The Oregon Health & Science University and University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Institutional Review Boards approved these studies.

Data Collection

A multidisciplinary research team with expertise in practice transformation, mixed-methods, and integrated care collected and analyzed data for both ACT and IWS. To understand clinical workflows and tasks supporting integrated care delivery, we analyzed practice surveys and conducted onsite observation at each site. Practice surveys were completed by the primary point of contact for each site and included questions about ownership, staffing patterns, turnover, and patient panel characteristics. Observation visits lasted between two to four days and included watching teams deliver integrated care and conducting interviews with 2–17 stakeholders (e.g., administration, clinicians, staff) depending on practice size. Interviews followed a semi-structured guide designed to clarify gaps in understanding around a practice’s clinical workflows and provide insight on how practice leaders helped develop and implement these workflows.

Data Management and Analysis

Practice information surveys were manually entered into Excel™ then transferred into SAS™ for analysis. Research team members took jottings during observation visits and used these to prepare rich, detailed fieldnotes, typically within 24 hours. Interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. Qualitative data (i.e., interview transcripts, fieldnotes) were de-identified and uploaded to Atlas.ti™ for analysis.

We conducted a descriptive analysis of quantitative practice survey data to describe the spectrum of practices participating in the study.

We analyzed qualitative data using multiple immersion-crystallization cycles27 to identify clinical workflows that support integrated care delivery. Qualitative data collection and analysis occurred concurrently. First, we immersed ourselves in the data, meeting weekly to analyze each case (i.e., individual practice) and explore the tasks, behaviors, and organizational factors that shaped delivery of integrated care. We tagged important segments of text using key words as codes (e.g., screening, warm-handoff). In a second immersion-crystallization cycle, we identified clinical workflows that supported integrated care delivery and explored when, how, and who performed the associated key tasks and behaviors. We conducted a third immersion-crystallization cycle and looked across the cases to understand how various contextual factors (e.g., staffing, physical space) impacted the ability of clinicians and staff to deliver integrated care clinical workflows.

RESULTS

The 19 participating practices included 12 primary care practices, three community mental health centers (CMHC), and four CMHC-Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) hybrids. All practices used an electronic health record (EHR); 16 practices (84%) allowed BHCs and primary care clinicians to document in the same EHR system. We observed 230 unique patient encounters during our observation visits, including 74.3% with primary care clinicians (n = 171), 26.5% with BHCs (n = 61), and 8.3% with psychiatrists (n = 8.3%). We conducted 160 total key informant interviews with BHCs (28.1%), primary care clinicians (27.5%), leadership (16.9%), medical assistants (10.6%) and other clinic roles such as care coordinators, front desk staff, and quality improvement leads (16.9%).

Key Workflow Phases in Integrated Care Delivery

We identified four key workflow phases in which teams delivering integrating care engaged: (1) Identifying patients needing integrated care; (2) Engaging patients and transitioning to the integrated care team; (3) Providing integrated care treatment; (4) Monitoring immediate treatment outcomes and adjusting treatment. Practices were refining clinical workflows and changing structural elements to improve integrated care delivery based on real-time learnings. Below, we describe these clinical workflow phases and provide examples of what happens when supporting structural components for these workflows are missing or underdeveloped. Table 2 summarizes these findings and provides references for ACT/IWS publications that describe the identified behaviors/tasks and structural factors in greater detail.

Table 2.

Clinical Workflows and Structural Factors that Facilitate or Impede Delivery of Integrated Care

| Workflow Phase | Behaviors and Tasks that Support Clinical Operationalization of Integrated Care | Factors That Serve as Barriers or Facilitators to Target Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Identify Patients Needing Integrated Care | • Allow for provider/staff discretion, but also use medical and behavioral health screening tools to identify patient needs (e.g., systematic screening, follow-up on clinical discretion).13, 16, 20

• Develop and implement standards and protocols for screening intervals (e.g., annually). • Schedule morning team huddles to review clinical schedule and strategize around patient’s integrated care needs.20 |

• Develop one EHR system and ensure that primary care and behavioral health patient information is easily available to all.17 • Establish documentation protocols for entry of integrated care screening data (discrete and numerical fields).17 • Staff clinical team members so that all are available to participate in team huddles.22 |

| Engage Patients and Integrated Care Team | • Develop protocols (including scripts) for transitioning patients between integrated care team members (e.g., primary care clinicians, behavioral health, other supportive staff).19, 20 • Establish methods and physical structures that enable behavioral health and primary care clinicians to quickly brief each other about patient needs.20, 23 |

• Establish processes that enable access to integrated services at the point of care (e.g., adequate staffing, scheduling, access structures).13, 22 |

| Provide Integrated Care Treatment | • Conduct rapid assessments and determine appropriate level for patient care.13, 20 Provide brief, problem-focused treatments tailored to integrated care setting (e.g., relaxation, self-care).26 • Develop and reinforce shared treatment plans.20 • Facilitate linkages to additional services (e.g., consulting psychiatry, traditional mental health, substance use treatment) if needed using established clinical pathways.13, 19 |

• One shared EHR enables supplemental review of patient’s record to provide additional details and care foundation (e.g., prior encounters with other BHCs).17, 20 • Document treatment/encounter notes in EHR templates according to clinic specified protocols.17 |

| Monitor Integrated Care Outcomes and Adjust Treatment | • Follow-up with patients during routine primary care appointments and schedule as needed integrated appointments.22 • Identify framework for when patient treatment needs to escalate to higher levels of care (e.g., specialty services).13, 20 • Update shared treatment plan with relevant adjustments in level of care; share patient encounter details with other integrated team members as clinically indicated (e.g., cc encounter note, face-to-face debrief) to facilitate treatment monitoring.19, 20 |

• Develop tracking tools in the EHR; Build capacity to run queries for monitoring patient-level process (e.g., referral status) and clinical outcomes (e.g., PHQ9 scores, HbA1c).16, 17 • Reinforce scheduling to support real-time interactions and hold complex case management meetings so team members can strategize when patients need adjustments in integrated care.22 |

Identifying Patients Needing Integrated Care

A critical workflow for integrated care was to identify patients in need of psychosocial care. Practices created workflows that allowed for provider/staff discretion in identifying patients and supported systematic screening. One BHC described both workflows in her clinic:

…All new patients get screened [for behavioral health needs]. It’s a vital sign that we use in our EHR that’s done just like blood pressure and is recorded in the chart….If the [screening] is positive…the nurse or the medical provider will come get us. Or if anything happens during the visit, they’ll come to us. (BHC Interview, Practice 2)

As noted in the quote above, clinicians and staff could identify patients who described or displayed behavioral health needs during appointments. In addition, some practices implemented “huddles” so that primary care, BHCs, and other staff could jointly review the clinical schedule and proactively identify individuals who might benefit from integrated care (e.g., prior positive screen that went unaddressed, personal knowledge). Huddles had the added benefit of allowing teams to strategize and adjust the timing of care tasks and who would support key activities during the scheduled encounter.

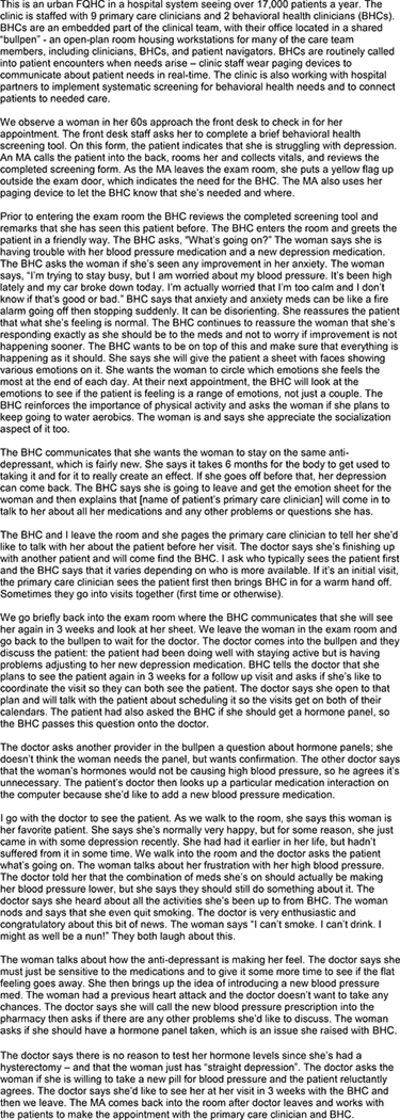

In addition to provider/staff discretion, practices developed workflows that supported patient identification through systematic screening. Practices administered various screening tools designed to detect conditions such as depression and anxiety (e.g., PHQ-2, PHQ-9, GAD-7), substance misuses (DAST, AUDIT), or unmet social needs. Screening occurred using paper-based forms, electronic tablets, or through verbal inquiry and direct entry into the EHR. More detailed follow-up screens were sometimes administered following a positive initial screen. As illustrated in the case example in Figure 1, brief screenings initiated by front desk staff during check-in or by medical assistants (MAs) during rooming aligned with existing workflows. Practices also had to decide how often they would screen their general patient population (e.g., annually, at each visit) as well as when they would re-screen patients receiving integrated treatment. Many practices screened patients systematically at every visit. A few, however, incorporated protocols or clinical decision support tools to re-screen patients at specified intervals (e.g., annually, 6-months).

Figure 1:

Case Study – Screening, Briefing, and Follow-up through Integrated Appointments in Practice 16.

Staffing, scheduling and EHR features could support or impede patient identification. A shared EHR with discrete fields facilitated entry and transfer of clinical screening data. Some practices built, activated, or tailored their EHR systems to have easy-to-use templates for common screening tools (e.g., PHQ-2, GAD-7) and decision support tools to alert health care professionals when screening or integrated care was needed. Part time BHCs or those covering multiple medical providers were often unable to participate in team huddles and alternate workflow strategies were developed. For instance, one part-time BHC always missed the morning huddle; rather than schedule a second huddle at noon, the MA and primary care clinician dyad flagged the BHC in the EHR on patients that may need integrated care.

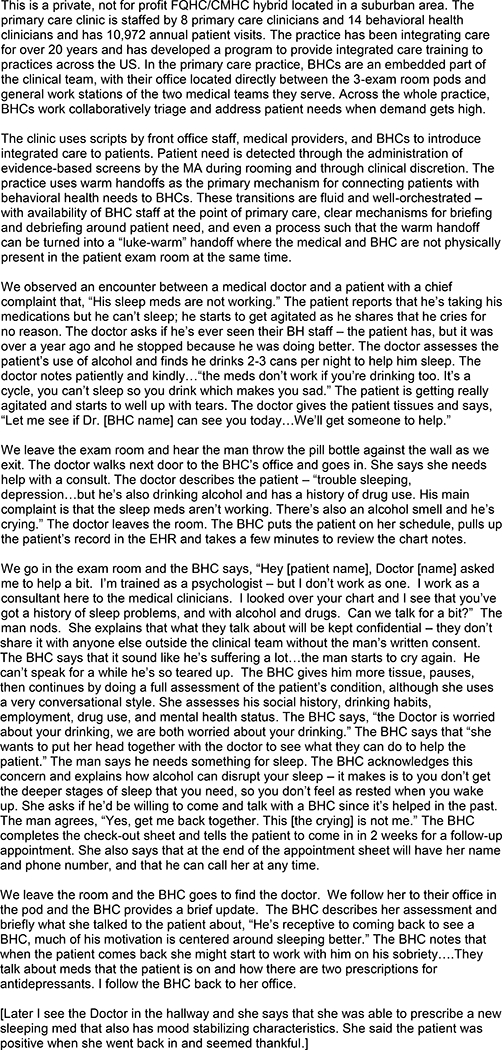

Engaging Patients and Transitioning to the Integrated Care Team

Following patient identification, a critical workflow was to communicate with the patient about integrated care and initiate the transition to the BHC. Practices developed protocols and scripts for practice members to use when transitioning patients among integrated care team members. These protocols set a strong foundation for engagement in services and established that attention to physical and behavioral health needs was “just what the practice does here.” Practice members described how patients got confused or offended when the language and/or clinical workflow to transition patients between primary care and BHCs was unclear, noting this happened for their clinics early in implementation or with new staff. The case example in Figure 2 illustrates how a medical clinician locates and works with the BHC to engage a patient presenting with depression, substance misuse, and multiple chronic conditions in integrated care.

Figure 2:

Case Study - Clinical Scripts, Point-of Care Access, and Delivery of Team-based Integrated Care in Practice 2.

As illustrated in the second case example (Figure 2), medical clinicians and BHC staff had important roles handing off and receiving the patient transition. Medical clinicians initiated discussions about integrated care with patients by describing the practice’s commitment to whole person care, introducing the BHC as a member of the care team, reinforcing his/her trust in the BHC, and emphasizing how the BHC was an expert qualified to help with the patient’s presenting need. The following quote illustrates this transition from the perspective of a medical provider:

…I might say to a patient, “Hey, I’m working with [BHC name]. She’s my BHC…and you’ve brought up that Johnny is having trouble with anxiety attacks. Can I bring her in to help with this?” And I’ll say, “She’s a counselor by training. This is exactly what she’s here for, and she can help us work on this.” (Medical Provider Interview, Practice 3)

To support the patient transition, BHCs would come into the same clinical exam room to initiate contact with the patient. Outside the exam room, medical clinicians/staff would sometimes brief the BHC on emergent patient needs – enabling the BHC to initiate their interaction with the patient by reiterating their role on the team, describing their initial knowledge of the patient’s situation, and emphasizing their ability to contribute to the patient’s care. “Mini-huddles” between integrated team members were used to provide updates on new and existing patients throughout the day and could be very brief (less than 1 minute) for experienced, high functioning teams who had refined their workflow and communication practices by working together over time.

Protocols for care team interruptions, close physical proximity, adequate staffing/scheduling, and the ability for ancillary staff to swiftly reorganize workflows (e.g., labs before the BHC encounter, BHC in before the medical clinician such as displayed in Figure 1) facilitated point of care access. Practices that were understaffed (e.g., part-time BHC, one BHC covering multiple practices/clinicians) or used 50–60 minute appointments for BHC encounters (similar to traditional mental health scheduling) experienced challenges in enabling the transition to and initial engagement with integrated care.

Providing Integrated Care Treatment

The ability of the BHC to provide brief intervention/treatment following the patient transition and to determine the appropriate level of care was an important workflow phase (see Figures 1 and 2). To achieve these goals, BHCs displayed a blend of utilizing strategies to build rapport, concurrent delivery of interventions suited to primary care (e.g., addressing basic coping skills, stress management), and conducting rapid and focused assessments that built on prior data (e.g., history, screening results from the brief or EHR). For patients who could be managed in primary care, BHCs worked to develop and implement a shared care plan (e.g., a record that summarized the problem, concern, outlined a course of treatment, and ensured the patient and all involved clinicians were on the same page regarding goals and responsibility) with the primary care clinician and clinical team. Some patients could not be managed in the integrated care setting and required triage to additional services (e.g., traditional mental health, substance use treatment). Although referral out could be supported by ancillary staff, BHCs played a critical role in facilitating access to the right level of care based on their knowledge of available services, as illustrated by the following quote:

[BHC] notes that it’s their job to know the right level of care for the patients. [This system has] 13 different programs for patients – including partial programs and day treatment. They also have counseling services, which they consider specialty BH… One thing that’s unique about this site is that they have one of the largest hospital and behavioral health systems in the country…They’ve worked to build the right continuum of care for their patients. (Fieldnotes, Practice 5)

Prior experience of BHCs in settings external to the primary care clinic facilitated knowledge of and access to additional levels of needed behavioral health care.

BHC scheduling and EHR features played a critical role in shaping treatment workflows. Separate EHR systems or restrictions in access to the full patient record resulted in workflow disruptions as team members had to look in multiple locations – or simply lacked understanding of the full scope of a patient’s care. A BHC’s ability to provide treatment was also facilitated by strategic scheduling, including: a) building BHC appointment templates to mirror primary care clinic flow (e.g., 15–30 minute visits versus one hour); b) scheduling follow-up appointments at quiet times in the clinic; c) blocking out visits when primary care patient volume was highest to enable consults at the point of care; and d) allowing BHCs to manage their own schedules (e.g., scheduling follow-ups; adding patients seen during a warm hand-off). The following quote illustrates how BHCs in one practice tailored their schedules to match the cadence of primary care:

“[My schedule] is based on the patterns of my clinic. I schedule the beginning of the day with follow-up patients. I usually schedule about 10 in 30-minute increments, even though I know I’m not going to spend more than 15 to 20 minutes with them. But that gives me some flexibility because then I know that every hour I can absorb at least one more patient if everybody shows up….[Clinic patterns are] somewhat unpredictable, but in general I know that the clinic has to get churning an hour and a half or so before I hit my peak volume times in terms of warm handoffs, or what we call “on demands.” So I will also put an admin spot in my schedule at those high-volume times. That doesn’t mean that I can only work a patient in during that time, that’s a buffer…that’s my catch-up time.” (BHC Interview, Practice 2)

Monitor Integrated Outcomes and Adjust Treatment Plans

A final workflow step involved tracking and adjusting patient treatment plans. In general, ACT and IWS practices and integrated teams were developing and refining tools and protocols to support patient monitoring. Some practices established protocols to follow-up with integrated care patients during routine primary care appointments or scheduled two to six brief visits with the BHC and specified when to escalate patient treatment to higher levels. A few practices created new positions (e.g., panel managers) to support proactive screening, monitoring and outreach to patients receiving integrated care. As illustrated in the case example in Figure 1, the primary care clinician and BHC strategically scheduled their follow-up appointment together to enable monitoring of the patient’s depression and medication changes.

Integrated care team members also used brief consults by phone or in person to inform treatment plan adjustments, as illustrated in the following interaction between a consulting psychiatrist, pharmacy manager, and primary care clinician.

…the consulting psychiatrist calls the pharmacy manager on her cell. The psychiatrist says he needs help. A patient this morning was stable but struggled after a medication change…The psychiatrist [already] consulted with the patient’s primary care provider. The patient was doing well on [Med A], but not good with [Med B]. The patient would rather risk the medical symptoms than change the medication and “start drugging/drinking again.” The EHR says it’s a Level 3 interaction – more study needed. It looks like the patient may need a higher dose of [Med B] based on how [Med A] interacts with the blood serum. They make a plan to override the warning and flag the primary care provider to increase [Med B]. (Fieldnotes, Practice 2)

Treatment adjustments were supported when practices had a shared EHR with full access to BHC and primary care notes and staffing/scheduling patterns that enabled real-time consultation with integrated team members. Many practices had EHRs that could not initially track integrated care quality indicators – a few had reporting features that could help track patient-level clinical (e.g., PHQ9 scores, HbA1C) and process outcomes (e.g., referrals status). Many clinics were building these features in their EHRs. In the absence of these features, some BHCs used excel templates or other databases to monitor patient outcomes and referral status.

DISCUSSION

Four important clinical workflow phases enabled delivery of integrated primary care and behavioral health across 19 diverse U.S. practices: (1) Identifying patients needing integrated care; (2) Engaging patients and integrated care team; (3) Providing integrated care treatment; and (4) Monitoring outcomes and adjusting integrated care treatment based on patient response. BHCs, primary care clinicians, and clinical staff performed important tasks and behaviors within each phase – often guided by protocols or scripts – to support workflows for integrated care that were timely and patient centered. As described for each workflow phase, staffing, scheduling, and/or EHR features could facilitator or impede integrated care delivery. Additionally, while all practices were developing and refining their workflows in real-time; it is notable that the workflow for monitoring outcomes and adjusting treatment was the least developed across the practice sites.

A growing number of resources are designed to help practices implement integrated care by providing templates for clinics to review and tailor critical workflow components (e.g., detecting patient need, creating communication structures) to the local setting.9, 10 This manuscript addresses gaps in the field by describing the behaviors and tasks practices use to operationalize integrated care delivery. Although authors note the importance of staffing and EHR features on integrated care delivery, few have described how they directly shape integrated care clinical workflows.17, 22, 28 Our present study leverages prior work from ACT and IWS by presenting a comprehensive summary of workflows that enable delivery of integrated care and links to articles that describe facilitating and impeding factors in greater detail (see Table 2).13, 15–26

There are a few limitations with the current work. First, we studied practices with varied models of integrated care and different resources and experience implementing these new approaches. Additionally, while much of our data was longitudinal, only cross sectional data was collected on a sub-set of more experienced practices. As such, we may have missed key changes in workflows over time. Second, although we studied both primary care and CMHCs that had integrated care, our findings predominantly focus on the experience of primary care clinics integrating behavioral health. This may be because CMHCs often embedded small integrated clinics within their larger traditional mental health care delivery system. Third, we used observational and interview data to identify clinical workflows associated with integrated care delivery. It is possible that activities focused specifically on generating workflows may have yielded different or more “ideal” results. Despite these challenges, our study provides critical insight into what, how, and who performs key tasks and behaviors to support delivery of integrated care and identifies factors that can help or hinder these workflow processes.

Refined integrated care workflows can help professionals from different backgrounds consult, coordinate, and collaborate to deliver integrated care.19 Practices and policy makers stiving to increase quality of care, help bend the cost curve, and improve the patient and provider experience1 by implementing integrated care should attend to these workflow phases - and the critical way staffing, scheduling, and EHR features shape care delivery.17, 22 Support in the form of practice facilitation or technical assistance from outside resources may enable practices to reflect upon and enhance workflows to support delivery of integrated care over time.29–32 Even with workflows in place, practices may concurrently need to address other structural elements of integrated care delivery, including training,24 organization of physical space,23 and cultural differences of behavioral health and medical professions.13, 18 Given the impact of integrated care on clinical outcomes and patient experience of care in ACT and IWS settings,15, 26 we encourage practices to consider our findings as they progress along their journey to integrate behavioral health and primary care.

CONCLUSION

Delivering integrated behavioral health and primary care requires practices to establish workflows that enable patient identification, engagement, treatment, and monitoring/adjusting care. This manuscript extends prior work from ACT and IWS and address key gaps in knowledge by providing an empirical description of the clinical workflows – and their associated tasks and behaviors – that enable delivery of integrated care. Findings highlight the importance of access to integrated care team members through staffing, scheduling, and refinement of EHR features. Findings provide a reference point for researchers, health system leaders, and policy makers working to operationalize integrated care and highlight the importance of process improvement over time.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participating Practices at Baseline (N = 19)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Initial Practice Type* | |

| Primary Care Clinic | 12 (63) |

| Community Mental Health Center | 3 (16) |

| Both | 4 (21) |

| Practice Ownership | |

| Private | 9 (47) |

| Hospital system | 5 (26) |

| Clinician owned | 4 (21) |

| Government owned | 1 (5) |

| Geographic Setting | |

| Urban | 6 (32) |

| Suburban | 9 (47) |

| Rural | 4 (21) |

| Annual patient visits, Mean (Range) | 52,557 (4,680 – 298,168) |

| Primary Care Clinician Staffing | |

| Number, Mean (Range) | 15.4 (0–71.0) |

| FTE, Mean (Range) | 13.0 (0 – 70.0) |

| Behavioral Health Clinician Staffing | |

| Number, Mean (Range) | 5.4 (0–26.0) |

| FTE, Mean (Range) | 4.6 (0 – 22.8) |

| Integrated Care Features | |

| Embedded BHC on primary care team | 11 (58) |

| Shared office space for primary care and BHC | 8 (42) |

| Systematic screening for behavioral health needs | 13 (68) |

| BHCs can document in shared EHR | 16 (84) |

Key Messages:

Clinical workflows operationalize ideas about integrated care into individual and team-based tasks and behaviors.

We identified four workflow phases associated with integrated care delivery: identification, engagement, treatment, and care monitoring/adjustment.

BHCs, primary care clinicians, and clinical staff performed important tasks and behaviors within each phase – often guided by protocols or scripts

Electronic health records (EHR) features, staffing and scheduling structures, and other organizational factors could facilitate or impede integrated care workflows.

Findings can be used as a reference point for operationalizing integrated care and highlight the importance of process improvement over time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Contributors/Acknowledgements: The authors are thankful to the 19 participating practices. Larry A. Green, MD and Frank deGruy III, MD provided helpful comments preparing this manuscript.

Funders: This research was supported by grants from the Colorado Health Foundation (CHF-3848), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality - 8846.01-S01

Tides Foundation/CalMHSA Integrated Behavioral Health Project - AWD-131237

Maine Health Access Foundation - 2012FI-0009. Dr. Davis is supported in part by a Cancer Prevention, Control, Behavioral Sciences, and Populations Sciences Career Development Award from the National Cancer Institute (K07CA211971).

DECLARATIONS

Ethical Approval: The Oregon Health & Science University and University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Institutional Review Boards approved this study.

Conflict of Interest Statements: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Prior Presentations: Portions of this work were presented during the 2014 Practice-based Research Network (PBRN) Annual Meeting in Bethesda, MD.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The Triple Aim: Care, Health, And Cost. Health Affairs. May 1, 2008 2008;27(3):759–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Comprehensive-Primary-Care-Initiative/index.html. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- 3.Kathol RG, deGruy F, Rollman BL. Value-Based Financially Sustainable Behavioral Health Components in Patient-Centered Medical Homes. The Annals of Family Medicine. March 1, 2014 2014;12(2):172–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solution. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- 5.Academy for Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care. http://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov.

- 6.Miller BF, Ross KM, Davis MM, Melek SP, Kathol R, Gordon P. Payment reform in the patient-centered medical home: Enabling and sustaining integrated behavioral health care. Am Psychol. January 2017;72(1):55–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peek CJ, the, National Integration Academy Council Lexicon for Behavioral Health and Primary Care Integration: Concepts and Definitions Developed by Expert Concensus Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blount A Integrated Primary Care: Organizing the Evidence. Families, Systems, & Health. 2003;21:121–134. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safety Net Medical Home Initiative. Organized, Evidence Based Care: Behavioral Health Integration: Safety Net Medical Home Initiative; 2014.

- 10.AIMS, Center: Advancing Mental Health Solutions. Collaborative Care Implementation Guide. http://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/implementation-guide. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- 11.O’Donnell C Business Process Analysis Workbook for Behavioral Health Providers: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and Center for Integrated Health Solutions (CIHS); 2013.

- 12.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Integration Playbook In: Korsen Neil MD, M.Sc.; Alexander Blount Ed.D.; Peek CJ Ph.D.; Kathol Roger M.D., C.P.E.; Narayanan Vasudha M.A., M.B.A., M.S.; Teixeira Natalie M.P.H.; Freed Nina M.P.H.; Moran Garrett Ph.D.; Newsom Allison B.S.; Noda Joshua M.P.P.; Miller Benjamin F. Psy.D., ed; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen DJ, Balasubramanian BA, Davis M, et al. Understanding Care Integration from the Ground Up: Five Organizing Constructs that Shape Integrated Practices. J Am Board Fam Med. Sep-Oct 2015;28 Suppl 1:S7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farb H, Sacca K, Variano M, Gentry L, Relle M, Bertrand J. Provider and Staff Perceptions and Experiences Implementing Behavioral Health Integration in Six Low-Income Health Care Organizations. J Behav Health Serv Res. August 03 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balasubramanian BA, Cohen DJ, Jetelina KK, et al. Outcomes of Integrated Behavioral Health with Primary Care. J Am Board Fam Med. Mar-Apr 2017;30(2):130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balasubramanian BA, Fernald D, Dickinson LM, et al. REACH of Interventions Integrating Primary Care and Behavioral Health. J Am Board Fam Med. Sep-Oct 2015;28 Suppl 1:S73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cifuentes M, Davis M, Fernald D, Gunn R, Dickinson P, Cohen DJ. Electronic Health Record Challenges, Workarounds, and Solutions Observed in Practices Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care. J Am Board Fam Med. Sep-Oct 2015;28 Suppl 1:S63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark KD, Miller BF, Green LA, de Gruy FV, Davis M, Cohen DJ. Implementation of behavioral health interventions in real world scenarios: Managing complex change. Fam Syst Health. March 2017;35(1):36–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen DJ, Davis M, Balasubramanian BA, et al. Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care: Consulting, Coordinating and Collaborating Among Professionals. J Am Board Fam Med. Sep-Oct 2015;28 Suppl 1:S21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen DJ, Davis MM, Hall JD, Gilchrist EC, Miller BF. A Guidebook of Professional Practices for Behavioral Health and Primary Care Integration: Observations From Exemplary Sites. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis MM, Balasubramanian BA, Waller E, Miller BF, Green LA, Cohen DJ. Integrating Behavioral and Physical Health Care in the Real World: Early Lessons from Advancing Care Together. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. September 1, 2013 2013;26(5):588–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis MM, Balasubramanian BA, Cifuentes M, et al. Clinician Staffing, Scheduling, and Engagement Strategies Among Primary Care Practices Delivering Integrated Care. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. September 1, 2015 2015;28(Supplement 1):S32–S40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunn R, Davis MM, Hall J, et al. Designing Clinical Space for the Delivery of Integrated Behavioral Health and Primary Care. J Am Board Fam Med. Sep-Oct 2015;28 Suppl 1:S52–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall J, Cohen DJ, Davis M, et al. Preparing the Workforce for Behavioral Health and Primary Care Integration. J Am Board Fam Med. Sep-Oct 2015;28 Suppl 1:S41–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallace NT, Cohen DJ, Gunn R, et al. Start-Up and Ongoing Practice Expenses of Behavioral Health and Primary Care Integration Interventions in the Advancing Care Together (ACT) Program. J Am Board Fam Med. Sep-Oct 2015;28 Suppl 1:S86–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis MM, Gunn R, Gowen K, Miller BF, Green LA, Cohen DJ. A qualitative study of patient experience of care in integrated behavioral health and primary care settings: more similar than different. Translational Behavioral Medicine. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borkan J Immersion/crystallization In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1999:179–194. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunter C, Goodie J. Operational and Clinical Components for Integrated-Collaborative Behavioral Healthcare in the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Families, Systems, & Health. 2010;28(4):308–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roderick SS, Burdette N, Hurwitz D, Yeracaris P. Integrated behavioral health practice facilitation in patient centered medical homes: A promising application. Fam Syst Health. June 2017;35(2):227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Robinson A, Niebauer L, Ford A. Practice facilitators and practice-based research networks. J Am Board Fam Med. Sep-Oct 2006;19(5):506–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis MM, Howk S, Spurlock M, McGinnis PB, Cohen DJ, Fagnan LJ. A qualitative study of clinic and community member perspectives on intervention toolkits: “Unless the toolkit is used it won’t help solve the problem”. BMC Health Serv Res. July 18 2017;17(1):497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. Jan-Feb 2012;10(1):63–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]