Abstract

Left ventricular (LV) thrombus after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a frequent complication that is associated with a risk of systemic embolism. Essential thrombocythemia (ET) has opposing tendencies towards hemorrhage and thrombogenesis and it can cause AMI via thrombogenesis. Ball-like LV thrombus is associated with a high risk of systemic embolism. We describe surgical resection of LV ball-like thrombus from a patient with ET. A 60-year-old woman presented at our hospital with transient ischemic attack accompanied by transient hemiplegia. Ultrasonic cardiography revealed a mobile ball-like thrombus in the LV after transmural AMI of the anterior wall. We performed emergency LV thrombectomy because of the mobile LV thrombus with embolism. Platelet aberrations and pathological bone marrow findings were consistent with a diagnosis of ET. We administered the patient with anti-coagulation drugs and the DNA replication inhibitor hydroxycarbamide to decrease the platelet count. She continues to survive and is doing well without major postoperative complications.

<Learning objective: Essential thrombocythemia (ET) can cause acute myocardial infarction with left ventricular (LV) thrombus via thrombogenesis. After we describe surgical resection of LV ball-like thrombus from a patient with ET, the patient was administered with anti-coagulation drugs and the DNA replication inhibitor hydroxycarbamide to decrease the platelet count. The patient continues to survive and is doing well without major postoperative complications.>

Keywords: Ball-like thrombus, Acute myocardial infarction, Surgical resection, Myeloproliferative diseases

Introduction

Left ventricular (LV) thrombus is a frequent complication of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) that is associated with a risk of systemic embolism 1, 2. It is mostly mural [3], and mobile, pedunculated thrombi in the LV cavity are rare [4]. The risk for embolic accidents is higher for mobile LV thrombi than mural thrombi 5, 6.

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is a myeloproliferative disorder that is associated with hemorrhage and thrombosis. The disease can result in thrombus formation and acute vascular occlusion. Thromboembolic complications, especially thrombus in the cerebral, coronary, and peripheral arteries, are more frequent than hemorrhage in patients with ET [7].

Case report

A 60-year-old woman with no contributory personal or family history of cardiovascular or blood disorders developed chest pain, exertional dyspnea, wobble, and transient right hemiplegia. She was admitted to our hospital 1 week later with profound shock and orthopnea.

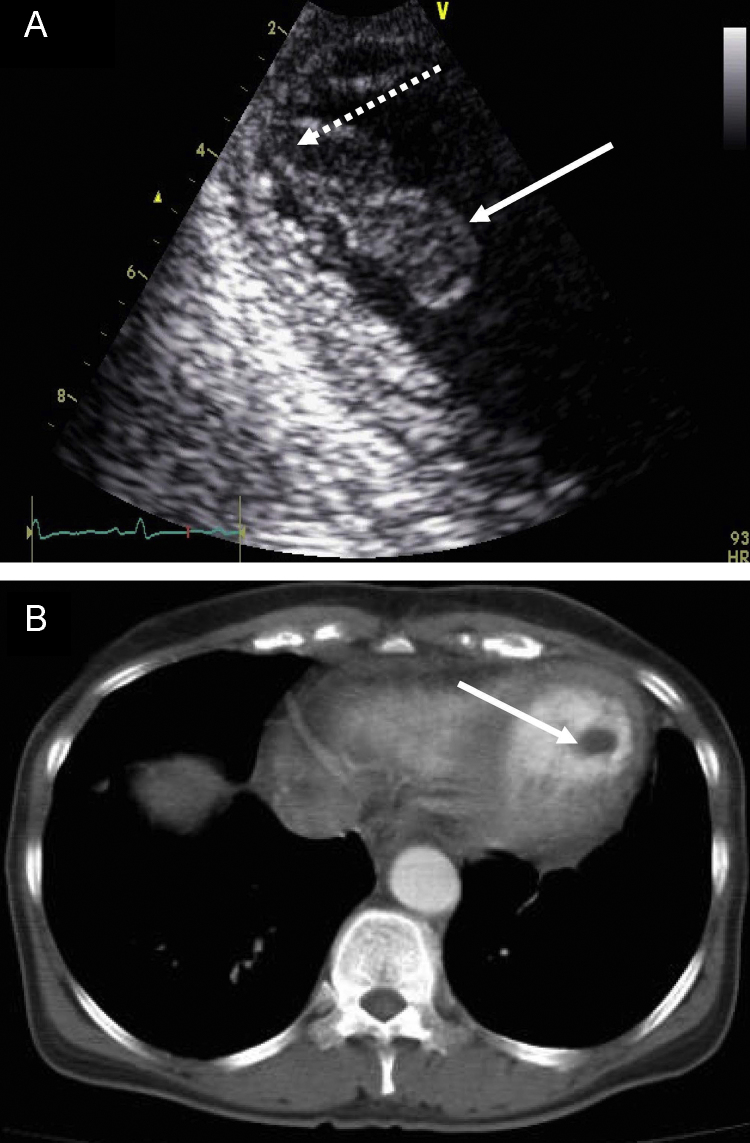

Electrocardiography (ECG) showed a QS-pattern in leads II, III, aVf, and V1-4, and a negative T-wave in leads aVL and V5-6. Laboratory findings were as follows: white blood cells, 12,900/mm3; platelets, 50.8 × 104/mm3; hemoglobin, 15.7 g/dL; serum creatine kinase (CK), 71 IU/L; CK-MB, 19 IU/L. Both fatty acid binding protein and troponin T levels were high. Transthoracic cardiac ultrasonography (UCG) showed asynergy in a large area of the left ventricle (LV) from the antero-septal to the apical region and a mobile, pedunculated mass attached by a stalk to the apex of the LV (Fig. 1A). The diameter of the mass was 39 mm and a pendulous motion coincided with the heartbeat. In UCG LV ejection fraction was 42% and LV end-diastolic and end-systolic dimension was 54/43 mm and there was mild mitral regurgitation. Computed tomography (CT) of the brain revealed no focal lesions of infarction and no bleeding. Enhanced CT of the chest showed a mass in the LV (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Transthoracic cardiac ultrasonography (A) and enhanced computed tomography (CT) (B). (A) Mobile abnormal mass with stalk in left ventricle (LV) revealed by transthoracic cardiac ultrasonography in long-axis view. Solid white arrow, mobile ball-like thrombus; dotted white arrow, stalk. Diameter of thrombus is 39 mm. (B) Enhanced CT shows mass in the LV. White arrow, thrombus with diameter of 18 mm.

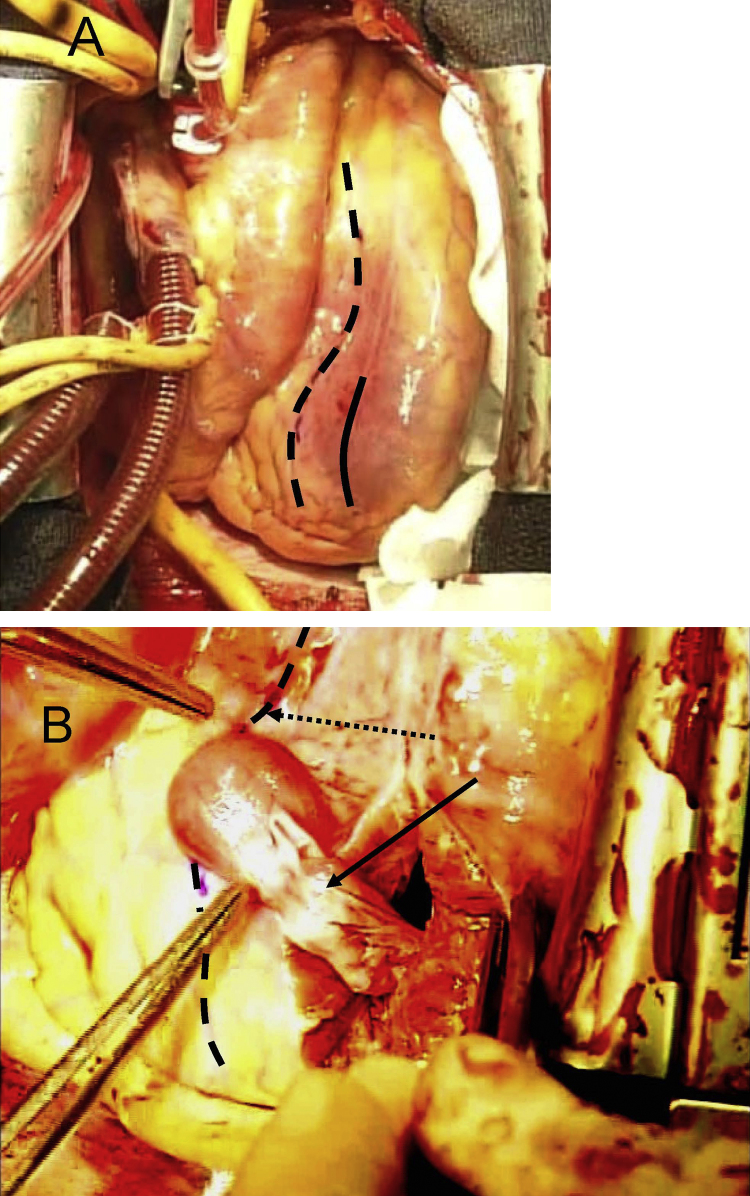

We diagnosed a mobile ball-like thrombus after myocardial infarction (MI) with transient ischemic attack (TIA). Because thrombus carries a risk of critical embolization, we performed emergency open heart surgery via a median sternotomy and found a considerable amount of pericardial effusion and fragile change due to MI in the anterior wall of the LV. Cold blood cardioplegia was delivered in an antegrade fashion and then the base of the ventricle to the apex parallel to the left anterior descending branch (LAD) was incised (about 5 cm) under a standard cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) (Fig. 2A). A fragile ball-like thrombus of about 4 cm in diameter attached from the apex to the trabeculae of the ventricular wall was completely resected (Fig. 2B). The ventriculotomy was simply closed in a linear fashion with reinforcement using felt strips. No events occurred after weaning the patient from CPB and postoperative complications did not arise.

Fig. 2.

Removal of left ventricular (LV) thrombus via median sternotomy. (A) Operative photograph taken under standard cardiopulmonary bypass. Access to allow LV opening was via incision (solid black line) of about 5 cm from ventricle base to apex parallel to left anterior descending (LAD) branch (dotted black line). (B) Black arrow, thrombus. Operative photograph taken immediately before thrombus removal. Dotted black line, LAD.

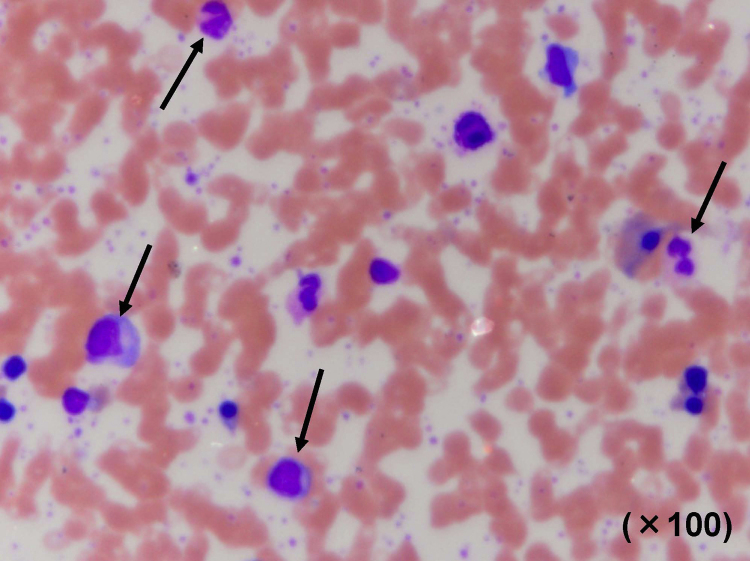

She was subsequently treated with anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs (heparin, aspirin, and warfarin) to prevent the formation of new thrombus and to dissolve multiple extant thrombi. On postoperative day (POD) 17, coronary angiography showed that the proximal region of the LAD was obstructed by abundant thrombus. Left ventriculography showed akinetic anterior wall motion and the absence of thrombus in the LV. Her postoperative platelet count was maintained around 100 × 104/mm3. On POD 33, the platelet count increased to 177 × 104/mm3 and a bone marrow examination revealed dense megakaryocytes (Fig. 3). She was diagnosed with ET and hydroxyurea was administered. The platelet count was stabilized at around 50 × 104/mm3. No remarkable events occurred during the clinical course.

Fig. 3.

Representative photomicrograph of bone marrow stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Arrow, megakaryocytes.

Discussion

ET is a myeloproliferative disorder characterized by abnormal megakaryocyte proliferation and it causes thrombus formation in systemic arteries including the coronary arteries. The affected coronary artery is often occluded with a large amount of thrombus when AMI is associated with ET. LV thrombus develops in one-third of patients with anterior wall AMI and in far more with a large anterior infarction and congestive heart failure [8]. Most of such thrombi are of the immobile mural type, which has a low risk of systemic embolism [6]. Mobile, ball-like thrombi are rare but carry a significantly higher risk of embolism. The incidence of MI in patients with ET was reported as 9.4% [6]. The patients of MI and ball-like thrombi with ET were rarer than these cases. Since guidelines for treating MI with LV thrombus and ET have not been established, we needed to consider the most appropriate therapeutic strategy for our patient.

Our patient developed TIA due to an embolism. Upon admission, ECG revealed the QS-pattern in leads II, III, aVf, and V1-4, and a negative T-wave in leads aVL and V5-6. UCG revealed asynergic anterior LV wall motion and a mobile, pedunculated thrombus in the LV. ECG before the surgery revealed QS-pattern in the leads. We initially considered that the anterior LV wall was not viable. We decided not to perform pre-operative coronary angiography (CAG) to avoid the risk of new embolisms developing. The post-operative CAG showed that LAD was occluded and the territory of LAD had no viability as expected. The thrombus could be detected in the LAD by transit time flowmetry with color Doppler system intraoperatively. Some patients with ET after MI have undergone coronary revascularization [9], which might prevent the production of new embolisms.

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines indicate that LV thrombus should be treated by anticoagulation therapy with aspirin and warfarin [10]. The platelet count of our patient continued to postoperatively increase to about 180 × 104/mm3. We suspected ET and added hydroxyurea to control the platelet count, since platelets comprise a risk factor for the onset of coronary arterial thrombosis [9]. Our patient has remained free of postoperative complications because platelet aggregation was inhibited.

We completely resected a mobile ball-like thrombus from a patient with ET after AMI. The clinical course of the patient was uneventful under anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the collaboration of the staff at the Department of Cardiology, Wakayama Medical University.

References

- 1.Asinger R.W., Mikell F.L., Elsperger J., Hodges M. Incidence of left-ventricular thrombosis after acute transmural myocardial infarction: serial evaluation by two-dimensional echocardiography. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:82–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198108063050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minami H., Asada T., Gan K. Surgical removal of left ventricular ball-like thrombus following large transmural acute myocardial infarction using the infarction exclusion technique – David–Komeda procedure. Circ J. 2008;72:1547–1549. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-07-0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan R.A., Miller R.D., Edwards J.E., Parker R.L. Thrombo-embolism in acute and in healed myocardial infarction. 1. Intracardiac mural thrombosis. Circulation. 1952;6:1–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.6.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McManus B.M., Goldberg S.D., Triche T.J., Roberts W.C. Elongate thrombus extending from left ventricular apex to outflow tract: a rare complication of myocardial infarction diagnosed by two-dimensional echocardiography. Am Heart J. 1983;105:327–329. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90536-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stratton J.R., Resnick A.D. Increased embolic risk in patients with left ventricular thrombi. Circulation. 1987;75:1004–1011. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.5.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamada Y., Nozaki N., Miyamoto T., Ohta I., Tomoike H. Recurrent pedunculated thrombi in the left ventricle with myocardial infarction and thrombocythemia – a case report. Yamagata Med J. 1995;13:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perston F.E. Essential thrombocythemia. Lancet. 1982;1:1021. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visser C.A., Kan G., Lie K.I., Durrer D. Left ventricular thrombus following acute myocardial infarction: a prospective serial echocardiographic study of 96 patients. Eur Heart J. 1983;4:333–337. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimbiris D., Segal L.B., Munir M., Katz M., Likoff W. Myocardial infarction in patients with normal patent coronary arteries as visualized by cinearteriography. Am J Cardiol. 1972;29:724–728. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(72)90177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antman E.M., Anbe D.T., Armstrong P.W. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction) Circulation. 2004;110:e82–e292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]