Abstract

Introduction

Integrating diabetes self-management into daily life involves a range of complex challenges for affected individuals. Environmental, social, behavioural and emotional psychological factors influence the lives of those with diabetes. The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of a stress management group intervention based on acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) among adults living with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes.

Methods and analysis

This study will use a randomised controlled trial design evaluating treatment as usual (TAU) and ACT versus TAU. The stress management group intervention will be based on ACT and comprises a programme divided into seven 2-hour sessions conducted over 14 weeks. A total of 70 patients who meet inclusion criteria will be recruited over a 2-year period with follow-up after 1, 2 and 5 years.

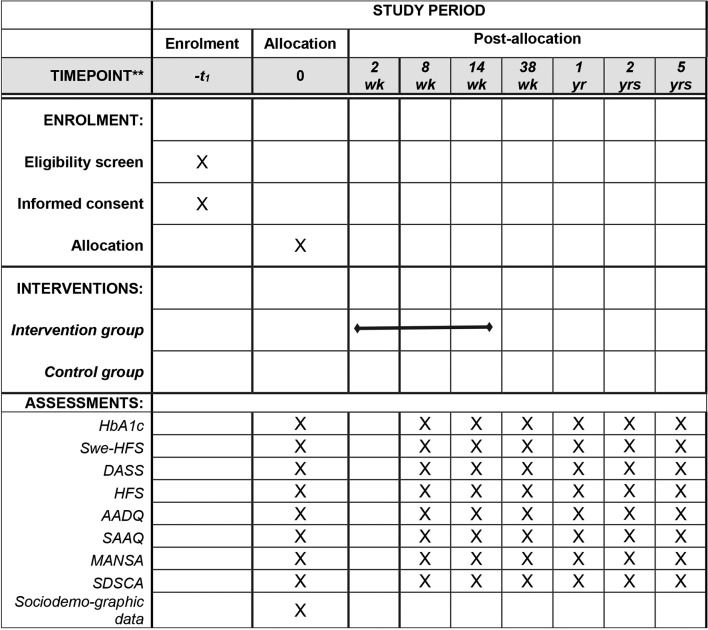

The primary outcome measure will be HbA1c. The secondary outcome measures will be the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, the Swedish version of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey, the Swedish version of the Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale, The Summary of Self-Care Activities, Acceptance Action Diabetes Questionnaire, Swedish Acceptance and Action Questionnaire and the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life. The questionnaires will be administered via the internet at baseline, after sessions 4 (study week 7) and 7 (study week 14), and 6, 12 and 24 months later, then finally after 5 years. HbA1c will be measured at the same time points.

Assessment of intervention effect will be performed through the analysis of covariance. An intention-to-treat approach will be used. Mixed-model repeated measures will be applied to explore effect of intervention across all time points.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has received ethical approval (Dnr: 2016/14-31/1). The study findings will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications, conferences and reports to key stakeholders.

Trial registration number

NCT02914496; Pre-results.

Keywords: acceptance and commitment therapy, diabetes, type 1, self-care, psychological stress

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a randomised controlled trial, considered the gold standard for a clinical trial. The study will evaluate the impact of a stress management group intervention among adults living with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes.

The intervention is theory driven and builds on behavioural research relevant with respect to the complex challenges for those living with type 1 diabetes.

The stress management programme has previously been conducted and scientifically evaluated in many contexts with promising and significant results. Research in the field of type 1 diabetes care and acceptance and commitment therapy is scarce; thus, this study will contribute to further knowledge.

Some of the outcome measures have not yet been properly validated, making it difficult to draw conclusions.

Introduction

Adherence to self-management involves regular attention to a range of daily self-care activities including insulin injection, self-monitoring of blood glucose, regulated mealtimes and exercise, good problem-solving skills, healthy coping skills, as well as risk-reduction behaviours.1 Together, these behaviours have been found to be positively correlated with good glycaemic control (HbA1c), reduced diabetes-related complications and improved quality of life (QoL).2 3 Currently Swedish registry data show that approximately 22% of patients with type 1 diabetes reach treatment goals <52 mmol/mol and that 20% are far above this level with measured HbA1c>70 mmol/mol.4

Significant self-management burden is well known among individuals and families living with diabetes. Furthermore, depression is at least three times higher in people with type 1 diabetes than in healthy individuals.5 Diabetes distress is common and mental illness has been shown to be associated with poor disease control, and decreased health and QoL in this group of individuals.6 7 Other psychological issues to be highlighted are anxiety, such as anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety unique to diabetes, such as fear of complications, hypoglycaemia and invasive procedures, as well as eating disorders.8

Different intervention methods based on cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) have been presented as promising alternatives in the treatment of diabetes and have also been tested in some previous studies. The use of CBT in diabetes focuses on changes to concrete behaviours in everyday life in order to strengthen self-care, improve glucose control and well-being,9–11 and to treat comorbid depression.12 In the diabetes field, a Dutch research group has evaluated CBT-based online support for adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes that have depression. The intervention was effective in reducing depressive symptoms and diabetes-related emotional stress. However, no effect on metabolic control was observed.13 Our own previous treatment study in the field9 10 was the first to demonstrate statistically assured effects on HbA1c.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a relatively new form of CBT that has received international attention in recent years.14 The goal of ACT is to increase psychological flexibility by using acceptance and mindfulness strategies together with commitment and behaviour change strategies. Relatively short ACT interventions have demonstrated good results in a wide range of problems, such as drug abuse, chronic pain, anxiety, depression, ability to cope with psychosis, smoking, prejudices, occupational stress, fatigue depression, self-harmful behaviour, obsessive–compulsive disorder and epilepsy.15 These studies also showed that the improvements in treatment groups were explained (mediated) by a common mechanism of action, reduced emotional and cognitive avoidance.16 Some support also exists for ACT among individuals with type 2 diabetes, which has indicated changes in acceptance coping, self-management and HbA1c.17 Another Swedish study protocol have been published with the similar aim and setting as this one with yet no published data.18

Theoretical framework

ACT is based on experimental work regarding the influence of language and behaviour, that is, relational frame theory, which explains why cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance are common phenomena causing suffering among individuals.19

Cognitive fusion is where we get entangled with our thoughts and pushed around by them rather than observing and seeing them for what they are, that is just products of our busy minds.14

A fundamental assumption within ACT is that we not only avoid things that are actually dangerous or unpleasant, we also avoid thoughts, feelings and memories associated with being dangerous or unpleasant, the so-called experiential avoidance. ACT targets the process of thinking and reduces the behavioural and functional influence of thinking by working with acceptance and mindfulness processes. Instead of responding impulsively to what we think, we learn to act based on what the situation requires and with guidance or our own values and goals.19

An overlap between CBT and ACT exists, and both approaches have possible and helpful application in diabetes care. While CBT focuses on the development of personal coping strategies that target solving current problems and changing unhelpful patterns in cognition (eg, thoughts, beliefs and attitudes towards diabetes), ACT rather tries to teach people to accept their thoughts, feelings, sensations and private events and to behave in ways that are consistent with their own valued goals and life direction.20

Objective and hypothesis

The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of a stress management group intervention based on ACT in adults with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes.

The hypothesis is that an ACT intervention focusing on stress reduction will be helpful in managing type 1 diabetes, specifically, in terms of decreased HbA1c, improved QoL and self-care activities, reduced level of stress, anxiety, general and diabetes-related stress.

Methods and analysis

This study protocol was developed in accordance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials 2013 Statement.21 The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement has also been referred to when applicable.22

Study design and setting

The stress management programme entitled ‘Diabetes in balance’ is a two-arm randomised usual care controlled trial—treatment as usual (TAU) +ACT versus TAU. The study will be conducted at a Swedish hospital in Stockholm.

Figure 1 presents the flow of the participants through the study. The schedule of enrolment, intervention and assessments is shown in figure 2.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study.

Figure 2.

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials enrolment to assessment. AADQ, Acceptance Action Diabetes Questionnaire; DASS, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; HFS, Hypoglycemia Fear Survey; MANSA, Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life; SAAQ, Swedish Acceptance and Action Questionnaire; SDSCA, The Summary of Self-Care Activities; Swe-HFS, Swedish version of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey.

Participants and recruitment

A total of 70 adult patients with type 1 diabetes will be included in the study over a 2-year period. Patients meeting inclusion criteria will be recruited from an endocrine clinic in Stockholm, Sweden between September 2016 and September 2018. The sample will be identified by reviewing patients’ journals and obtaining data from the Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR).

Inclusion criteria

Patients will be eligible to participate in the study if they meet the following inclusion criteria: living with type 1 diabetes, with duration of at least 2 years, age 18–70 years. HbA1c should be >60 mmol/mol (reference value: <42 mmol/mol) at baseline of measurements and at the last two visits according to the medical record.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria include: untreated ongoing or severe psychiatric disease; recurrent depression; post-traumatic stress; ongoing cortisone treatment; newly commenced or altered treatment of thyroid disease; insulin pump therapy started within the last 3 months; ongoing intercurrent disease; protracted infection treatment (eg, osteitis); cancer under investigation or treatment; obesity surgery the latest 24 months; other conditions with weight change or pregnancy.

Patients fulfilling inclusion criteria will receive written information about the study and will be asked to participate. These patients will also be offered further verbally given information via telephone and when attending an appointment for baseline control of measures. At this baseline control, a research assistant will gather sociodemographic and clinical data, including sex, age, marital status, educational level, employment, diabetes duration, medication and diabetes-related complications. Prior to this baseline control, the patients will be invited by email to complete a battery of web-based questionnaires. For patients who need assistance to complete the web-based survey, the research assistant will be made available. The questionnaires are further described under the Measures section of this paper.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation will be done in blocks of 60 patients, with 30 in each study arm. Stratification will be used to ensure that the groups are balanced in relation to gender. A person who is not involved in the study will execute the randomisation and the researchers will be blinded to the participant’s random assignment.

Intervention

The intervention will consist of seven 2-hour group sessions using ACT techniques for managing stressful thoughts and feelings and exploration of personal values related to diabetes in order to act in a valued direction. Recurring themes for each session will be psychoeducational elements, group discussions, exercises, mindfulness practice, values clarification, role playing, metaphors, worksheets and homework to be followed up in the group by the leaders.

The seven sessions cover six core ACT processes to train psychological flexibility. These core processes include acceptance, cognitive defusion, being present, self as a context, values and committed action, which all are further described by Hayes et al.23

The session-by-session content of the intervention is described in table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the content in the acceptance and commitment therapy-based stress-management intervention

| Session 1 | Stress and acceptance. What is possible to change and what needs to be accepted? |

| Session 2 | The language. Avoiding thoughts and feelings. Thoughts can cause suffering. Mindfulness. |

| Session 3 | Values clarification: What is important to me in life? How do I want to live my life? |

| Session 4 | Values clarification, continuation: obstacles, language, thoughts, feelings and rules. |

| Session 5 | To live the life I want: identification of values in to increase value-based actions. |

| Session 6 | How thinking can cause pain and suffering Cognitive defusion and psychological flexibility. |

| Session 7 | To keep going: compassion, communication and repetition |

A licensed psychologist specialising in CBT, and a registered nurse specialising in diabetes care will lead the stress management programme according to a structured manual developed by one of the authors (FL) and further revised by two of the authors (TA and SA) to specifically fit people living with diabetes. Both group leaders have been trained in the ACT manual by FL, who is an internationally peer-reviewed and approved ACT trainer.

For quality assurance, a fidelity check will be performed by videotaping one session hold by the licensed psychologist and the registered nurse. The videotape will be reviewed by FL, the internationally peer-reviewed trainer.

Attendance will be recorded each session. After sessions 4 and 7, the participants in the intervention group will fill out an adherence evaluation. The aim is to measure how adherent each participant has been to the treatment interventions from the sessions and how well the group leaders have adhered to the treatment manual. The group leaders also evaluate their adherence to the manual. Thus, participants’ and group leaders’ evaluations can be compared. The participants and group leaders rate each intervention in the session on a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 = ‘this has not been discussed/brought up’, to 10 = ‘This was covered thoroughly’. The purpose is to see to what extent the participants have received the treatment described in the manual of the method.

Control group

Patients randomised to the control group will receive usual care, comprising annual appointments with a diabetes specialist nurse and a diabetes physician. In addition, the control group patients will be asked to answer web-based surveys and visit the clinic for a HbA1c blood test.

All study participants, both in the control and intervention groups, will receive a certificate of participation and 100 Swedish crowns at each measuring occasion after completing both the web-based survey and the HbA1c test.

Patient and public involvement

The results of the study will be communicated to participating patients through a popular scientific report. No other patient involvement has been included.

Measures

The primary medical outcome variable will be glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c). The secondary variables will be a set of self-reported questionnaires, chosen on the basis of the contents of the intervention: fear of hypoglycaemia (Swedish version of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey (Swe-HFS)),24 diabetes-related distress (Swedish version of the Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale (Swe-PAID-20)),25 Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS),26 acceptance of diabetes-related thoughts and emotions (Acceptance Action Diabetes Questionnaire (AADQ)),17 acceptance of thoughts and emotions (Swedish Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (SAAQ))27 Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA)28 and Summary of Self-Care Activities (SDSCA).29 Time points for measurements are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Time points of measurements

| Variable | w. 0 Inclusion |

w. 8 After session 4 |

w. 14 After session 7 |

w. 38 After 6 months |

w. 62 After 1 year |

w. 114 After 2 years |

After 5 years |

| Primary outcome measure | |||||||

| HbA1c | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Secondary outcome measures | |||||||

| Swe-HFS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Swe-PAID-20 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| DASS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| AADQ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| SAAQ | X | ||||||

| MANSA | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| SDSCA | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Sociodemographic data | X | ||||||

AADQ, Acceptance Action Diabetes Questionnaire; DASS, Depression, Anxiety Stress Scales; MANSA, Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life; SAAQ, Swedish Acceptance and Action Questionnaire; SDSCA, The Summary of Self-Care Activities; Swe-HFS, Swedish version of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey; Swe-PAID-20, Swedish version of the Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale.

HbA1c

Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) is the standard measure for evaluating glycaemic control over the previous 2 to 3 months (reference values for those <50 years: 27–42 mmol/mol, and 31–46 mmol/mol for those >50 years). Guidelines suggest a general target level for HbA1c of <52 mmol/mol.30

The Hypoglycaemia Fear Survey

The Hypoglycaemia Fear Survey (HFS)31 measures fear of hypoglycaemia using two subscales (Worry and Behaviour) consisting of 23 items that are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The Worry Subscale consists of 13 items measuring worry about different aspects of hypoglycaemia and its negative consequences. The Behaviour Subscale, however, consists of 10 items measuring to what degree different behaviours are used to avoid hypoglycaemia and its negative consequences. The total score for the HFS is 92 with 0 being the lowest score possible. A higher score indicates greater fear. The Swe-HFS is validated and shows good psychometric properties24 and will thus be used in this study.

Problem areas in diabetes

Diabetes-related distress will be measured by the Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale (PAID) developed by Polonsky et al.32 This scale comprises 20 statements capturing common negative emotions related to living with diabetes and its treatment. The 20 items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not a problem) to 4 (serious problem). The scores from the PAID Scale are summed and converted to a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating diabetes distress. A cut-off score of 40 or higher is often used to define diabetes distress. The original PAID Scale and the Swedish version of the scale (Swe-PAID-20), which will be used in this study, have been proven in terms of validity and reliability.25 32 33

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales

Depression, anxiety and stress will be measured with the DASS.26 This tool consists of three subscales (Depression, Anxiety and Stress), each of which comprises seven items referring to the past week. The 21 items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale. DASS was translated by Livheim34 by using a back-translation technique.35 DASS has shown good psychometric properties.36

Acceptance and Action Diabetes Questionnaire

Acceptance of diabetes-related thoughts and emotions will be measured using the AADQ,17 an 11-item scale grade on a 7-point Likert scale where 1=never true and 7=always true. The questionnaire measures emotional and cognitive avoidance related to diabetes. The psychometric properties of the Swedish version of AADQ will be simultaneously evaluated while this intervention study is carried out.

Swedish Acceptance and Action Questionnaire

Acceptance of thoughts and emotions will be measured by the SAAQ.27 The original version of the questionnaire (Acceptance and Action Questionnaire—II) was originally developed by Hayes et al.20 It measures emotional and cognitive avoidance and consists of six items rated on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1=never true and 7=always true. The Swedish version of the instrument shows good concurrent and convergent validity and satisfying internal consistency (α=0.85).27

Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life

The MANSA by Priebe et al 37 is a questionnaire with 16 items measuring QoL. Four of the questions measure objective QoL and 12 items cover general QoL and satisfaction with work, economic status, friendship, living arrangements, personal safety, family and physical health. QoL is rated on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 = ‘could not be worse’ to 7 = ‘could not be better’. Adding the 12 items and dividing the sum by 12 achieves the total score of general QoL. The objective items are dichotomous ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. MANSA is translated and validated in Swedish by Björkman and Svensson.28

The Summary of Self-Care Activities

The SDSCA measures the frequency of self-care behaviours over the past 7 days.29 The revised SDSCA consists of 11 items assessing aspects of the diabetes regimen as general diet, exercise, blood-glucose testing, foot care and smoking status. Each item is scored according to the number of days per week they are performed on a scale of 0–7. In this study, we will use the four two-item subscales regarding general diet, specific diet, exercise and blood-glucose testing. Each self-care component is assessed separately with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-care. The Swedish version of SDSCA translated by Amsberg et al 9 will be used in this study. Cronbach’s alpha for the subscales ranged from 0.80 to 0.86.9

Analysis

A minimum of 56 patients with type 1 diabetes need to be recruited to reach 80% power and to detect a clinical decrease in HbA1c of 6 mmol/mol assuming a SD of 9 with 5% significance level. With respect to drop-out rate, we aim to recruit a total of 70 patients who meet the inclusion criteria. The primary endpoint will be HbA1c levels 6 months after inclusion. Secondary endpoints will be HbA1c levels at other time points as well as scores from 10 self-reported questionnaires at each time point.

To assess the intervention effect at a specific time point, analysis of covariance will be applied.38 Specifically, at a given time point t, an outcome y(t) will be modelled through the linear regression equation:

where a and b are estimated coefficients, y(0) represents the baseline value and group is a binary variable coded as 1 for the intervention group and 0 for the control group. Coefficient b represents the difference between the average change of outcomes of each group and will be presented with a corresponding 95% CI. The F-statistic will be used to test for difference in average change between groups and a two-sided p value less than 0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

All statistical assessments will be performed according to an intention-to-treat strategy. To minimise effect of missing data on statistical power and bias of intervention effect, a multiple imputation approach using fully conditional specification models as implemented by the MICE algorithm in R software will be used.39

In secondary analysis, mixed-model repeated measures will be applied to explore the effect of intervention across all time points.39 In this model, the following factors will be included as fixed effects: (1) intercept, (2) time, (3) intervention and (4) intervention*time. Subjects will be modelled through a random factor assuming an unstructured covariance model. Additional adjustment for sociodemographic and clinical factors, including age at inclusion, educational level and diabetes duration will be considered in building the model. In addition, non-linear time effects will be explored through altering coding of time in the model as well as by considering piecewise linear trends separately for the initial phase up to 6 months after inclusion and the follow-up phase between 6 months and 5 years. To handle missing data, full maximum likelihood estimation will be applied.40

Number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve clinically significant reduction in HbA1c will be computed, where clinically significant reduction in HbA1c will be defined by a reduction of HbA1c of 5 mmol/mol.

Self-care (SDSCA) and acceptance (AADQ and SAAQ) will be explored as possible mediators of the ACT intervention effect on HbA1c levels according to the approach described by Baron and Kenny.41 Formal test for mediation will be performed through a bootstrap approach as proposed by Preacher and Hayes.42

Discussion

This study protocol presents the design of a randomised controlled trial study with the aim of evaluating the impact of a stress management group intervention based on ACT in adults with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes. The ACT-based intervention focusing on stress is expected to help improve glycaemic control, self-care activities, emotional and cognitive avoidance, diabetes-related distress, fear of hypoglycaemia, depression, anxiety and stress with subsequent beneficial effects on QoL. Previous studies in type 2 diabetes have found that the HbA1c level could be reduced using ACT.17 43 However, to date, there are no published data on whether or not a similar effect is evident in adults with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes. Improving glycaemic control is of importance due to the excess risk of mortality in those with poor glycaemic control.44 The ACT intervention has potential to improve glycaemic control due to including seven sessions covering all six core ACT processes to train psychological flexibility. These are acceptance, cognitive defusion, being present, self as a context, values and committed action, which all are further described by Hayes et al.23

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Fredrik Wiklund, Statisticon AB for statistical support.

Footnotes

Contributors: SA, FL, ET and TA took part in designing the study. SA wrote the first draft of the manuscript and led the development of the study protocol. TA and U-BJ contributed with texts about study measures and commented on the manuscript, which SA revised in a second version. All authors critically reviewed, revised and approved the final version to be submitted by SA.

Funding: This project was supported by grants from the Annie and Fritz Tjus donation fund, Sophiahemmet Foundation and Lindhés advokatbyrå AB (grant number LA2016-0429).

Competing interests: FL receives royalties from his own written books on ACT and income from training professionals in ACT.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the Regional Ethical Review Board (Dnr: 2016/14-31/1).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. AADE. AADE7 self-care behaviors. Diabetes Educ 2008;34:445–9. 10.1177/0145721708316625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Diabetes Association. 4. Lifestyle Management. Diabetes Care 2017;40(Suppl 1):S33–43. 10.2337/dc17-S007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thorpe CT, Fahey LE, Johnson H, et al. Facilitating healthy coping in patients with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Educ 2013;39:33–52. 10.1177/0145721712464400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Swedish National Diabetes Register. Annual report 2016. Swedish. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roy T, Lloyd CE. Epidemiology of depression and diabetes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2012;142(Suppl):S8–21. 10.1016/S0165-0327(12)70004-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:3278–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pouwer F, Nefs G, Nouwen A. Adverse effects of depression on glycemic control and health outcomes in people with diabetes: a review. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2013;42:529–44. 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Groot M, Golden SH, Wagner J. Psychological conditions in adults with diabetes. Am Psychol 2016;71:552–62. 10.1037/a0040408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Amsberg S, Anderbro T, Wredling R, et al. A cognitive behavior therapy-based intervention among poorly controlled adult type 1 diabetes patients--a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2009;77:72–80. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amsberg S, Anderbro T, Wredling R, et al. Experience from a behavioural medicine intervention among poorly controlled adult type 1 diabetes patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009;84:76–83. 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Snoek FJ, van der Ven NC, Twisk JW, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) compared with blood glucose awareness training (BGAT) in poorly controlled Type 1 diabetic patients: long-term effects on HbA moderated by depression. A randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med 2008;25:1337–42. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02595.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Freedland KE, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:613–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Bastelaar KM, Pouwer F, Cuijpers P, et al. Web-based depression treatment for type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2011;34:320–5. 10.2337/dc10-1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson K. Acceptance and commitment therapy. NewYork: Guilford, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15. A-Tjak JG, Davis ML, Morina N, et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy for clinically relevant mental and physical health problems. Psychother Psychosom 2015;84:30–6. 10.1159/000365764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Biglan A, Hayes SC, Pistorello J. Acceptance and commitment: implications for prevention science. Prev Sci 2008;9:139–52. 10.1007/s11121-008-0099-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gregg JA, Callaghan GM, Hayes SC, et al. Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007;75:336–43. 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lindholm-Olinder A, Fischier J, Fries J, et al. A randomised wait-list controlled clinical trial of the effects of acceptance and commitment therapy in patients with type 1 diabetes: a study protocol BMC Nurs 2015;14:1–5. 10.1186/s12912-015-0101-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hayes SC. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Relational Frame Theory, and the Third Wave of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies - Republished Article. Behav Ther 2016;47:869–85. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther 2006;44:1–25. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332 10.1136/bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hayes SC, Levin ME, Plumb-Vilardaga J, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behav Ther 2013;44:180–98. 10.1016/j.beth.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Anderbro T, Amsberg S, Wredling R, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Swedish version of the Hypoglycaemia Fear Survey. Patient Educ Couns 2008;73:127–31. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Amsberg S, Wredling R, Lins PE, et al. The psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale (Swe-PAID-20): scale development. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:1319–28. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther 1995;33:335–43. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lundgren T, Parling T. Swedish Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (SAAQ): a psychometric evaluation. Cogn Behav Ther 2017;46:315–26. 10.1080/16506073.2016.1250228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Björkman T, Svensson B. Quality of life in people with severe mental illness. Reliability and validity of the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA). Nord J Psychiatry 2005;59:302–6. 10.1080/08039480500213733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care 2000;23:943–50. 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018 . Diabetes Care 2018;41(Suppl 1):S55–S64. 10.2337/dc18-S006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cox DJ, Irvine A, Gonder-Frederick L, et al. Fear of hypoglycemia: quantification, validation, and utilization. Diabetes Care 1987;10:617–21. 10.2337/diacare.10.5.617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, et al. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care 1995;18:754–60. 10.2337/diacare.18.6.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Welch GW, Jacobson AM, Polonsky WH. The problem areas in diabetes scale. an evaluation of its clinical utility. Diabetes Care 1997;20:760–6. 10.2337/diacare.20.5.760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Livheim F. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in school – to cope with stress. 2004;2004:68 in Swedish. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales—a practical guide to their development and use. 5th edn New York: United States Oxford University Press Inc, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, et al. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav Res Ther 1997;35:79–89. 10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00068-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Priebe S, Huxley P, Knight S, et al. Application and results of the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA). Int J Soc Psychiatry 1999;45:7–12. 10.1177/002076409904500102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Altman DG, Gardner MJ : Altman DG, Machin D, Bryant TN, Regression and correlation. 2nd edn London: BMJ Books, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Van Buuren SG-O K. MICE: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hesser H, Gustafsson T, Lundén C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of tinnitus. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012;80:649–61. 10.1037/a0027021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;51:1173–82. 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 2004;36:717–31. 10.3758/BF03206553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Whitehead LC, Crowe MT, Carter JD, et al. A nurse-led education and cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention among adults with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes: A randomised controlled trial. J Eval Clin Pract 2017;23:821–9. 10.1111/jep.12725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lind M, Svensson AM, Kosiborod M, et al. Glycemic control and excess mortality in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1972–82. 10.1056/NEJMoa1408214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.