Abstract

Background

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of IBC were selected from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) chip data: GSE21422 and GSE21974. Network analysis of the DEGs and IBC-related genes was performed in STRING database to find the core gene. Thus, this study aimed to determine the role of NUSAP1 in invasive breast cancer (IBC) and to investigate its effect on drug susceptibility to epirubicin (E-ADM).

Material/Methods

The mRNA expression of NUSAP1 was determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (q-PCR). The protein expression was detected by Western blotting. Cell growth and growth cycle were detected by MTT assay and flow cytometry, respectively. Cell migration and invasion were tested by Transwell assay.

Results

Through use of gene network analysis, we found that NUSAP1 interacts with IBC-related genes. NUSAP1 presented high expression in IBC tissue samples and MCF-7 cells. NUSAP1 overexpression promoted the growth, migration, and invasion of MCF-7 cells. While NUSAP1 gene silencing downregulated the expression of genes associated with cell cycle progression in G2/M phase, cyclin D kinase (CDK1) and DLGAP5 arrested cells in G2/M phase and significantly inhibited the growth, migration, and invasion of MCF-7 cells. si-NUSAP1 increased the susceptibility of MCF-7 cells to E-ADM-induced apoptosis.

Conclusions

Our study provides evidence that downregulation of NUSAP1 can inhibit the proliferation, migration, and invasion of IBC cells by regulating CDK1 and DLGAP5 expression and enhances the drug susceptibility to E-ADM.

MeSH Keywords: Carcinoma, Ductal, Breast; CDC2 Protein Kinase; Cell Proliferation; Epirubicin; Nuclear Proteins

Background

Breast cancer is one of the tumors with the most effective therapies in clinical practice, in which metastasis and recurrence are major causes of death, and the pathological staging is significantly correlated with secondary metastasis [1]. Although invasive breast cancer (IBC) has been one of the focuses of tumor research in recent years, the variety of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in IBC makes the research very complicated and the molecular mechanism and metastasis pathway are still unknown. Therefore, it is of particular importance to determine the core gene involved in cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, and to study its effect on drug susceptibility to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in IBC.

Many cancer-related genes can be identified by bioinformatic methods before they are experimentally and clinically validated. In the study of breast cancer, DEGs in normal and cancer tissues can be screened by using the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and STRING database or by GSEA and meta-analysis. Then, the key genes related to breast cancer are identified by comparing the structure and function of breast cancer-associated genes in NCBI data. For instance, Zhou et al. screened candidate genes that may be involved in the molecular mechanisms of breast cancer, including previously reported genes FOS [2] and IL18 [3], and new genes that have not been studied, including MYC, ACTA2, and CD274. Nucleolar and spindle associated protein 1 (NUSAP1) can control the cell cycle by promoting the aggregation of microtubules, which play a crucial role in spindle assembly and formation. The protein expression of NUSAP1 changes periodically in the course of the cell cycle, accumulating in interkinesis and decreasing after mitosis [4]. There are extensive studies of the NUSAP1 gene in various tumors, and previous studies have shown that high expression of NUSAP1 can serve as a prognostic factor in breast cancer [5], liver cancer [6], prostate cancer [7], pancreatic cancer [8], oral squamous carcinoma [9], melanoma [10,11], and glioblastoma [12]. However, the role of NUSAP1 in IBC has not yet been reported.

In this study, the IBC-related gene NUSAP1 was screened by bioinformatics method. The protein interactions between NUSAP1 and CDK1/DLGAP1 were predicted by STRING database (http://string.embl.de/). We found that downregulation of NUSAP1 expression downregulated the expression of CDK1 and DLGAP1, as well as inhibiting proliferation, migration, and invasion of IBC cells and increasing the susceptibility of cells to epirubicin (E-ADM).

Material and Methods

Gene chip data processing

The data set GSE21974 was obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (http://www.nebi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) with “invasive breast cancer” and/or “neoadjuvant chemotherapy” as the key words. The chip platform was Agilent-014850 Whole Human Genome Microarray 4×44k G4112F (GPL 6480). GSE21974 included 57 samples (32 invasive breast cancer samples before treatment and 25 invasive breast cancer samples after treatment). GSE21422 was obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with “Human healthy tissue samples” and “DCIS and invasive mammary tumors” as key words.

PolySearch 2.0 database and network analysis

IBC-related genes were searched in PolySearch 2.0 (http://polysearch.cs.ualberta.ca/) with “invasive breast cancer” as the key words. PPI network diagram was established using diagnostic tools of STRING.

Collection of clinical specimens

Forty-five IBC patients who underwent radical mastectomy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy were selected in Xiangya Hospital. Inclusion criteria were: etiological diagnosis before chemotherapy, indication for radical resection and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: incomplete clinical data, serious organ diseases, lactation and pregnancy, and untreated patients.

Cell culture

IBC cell line IOWA-1T (ATCC® CRL-3292™) was purchased from the ATCC cell bank. Breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231, T47D, and MCF-7 and healthy mammary fibroblasts Hs578Bst were purchased from the Shanghai Cell Bank. Cells were cultured in 5% CO2 at 37°C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F-12 HAM (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 50 units/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Total RNA extraction and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (q-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol extraction kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Using Ready-To-Go You-Prime First-Strand Beads (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK), reverse transcription was conducted to obtain cDNA from 5 ug total RNA. NUSAP1 mRNA expression was examined by using the LightCycler 480 PCR system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Primers and universal probes were designed by the Universal Probe Library (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The primer sequences of NUSAP1 were as follows: forward 5′-CTGTGCTTGGGACACAAA-3′; reverse 5′-TTGTCAACTTGAATGGGGTAATAA-3′. The primer sequences of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were as follows: forward 5′-CATCTCTGCCCCCTCTGCTGA-3′; reverse 5′-GGATGACCTTGCCCACAGCCT-3′. The reaction condition was 10 min at 95°C and 45 cycles of 10 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 30 s at 72°C. Dissolution curve analysis was then performed. Each cell line was subjected to 3 independent repeated experiments.

Western blotting assay

Cells in the logarithmic growth phase were selected, washed once with PBS, and lysed with 200 μL 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to extract fresh protein. The protein was quantified using the Pierce protein quantitation assay kit. We transferred 50–100 μg protein to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) film after 12% SDS-PAGE gel separation and sealed it for 1 h with Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBST) containing with 5% milk. Then, the protein was incubated with anti-NUSAP1 antibody (ab93779; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-bcl-XL (ab32370; Abcam), anti-CDK1 (ab18; Abcam), and anti-DLGAP5 (ab84509; Abcam) overnight at 4°C or 2 h at room temperature, washed it 3 times with TBST (5 min each time), incubated it for 1.5 h with secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc) at room temperature, and rewashed it 3 times with TBST (10 min each time). β-actin was used as internal positive control. All Western blots shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Construction of overexpression vector

According to the sequence of the NUSAP1 gene, the primer sequence of its full-length cDNA was designed: forward 5′-GCG TTA CAG GCC CTT TGG CGC CTG-3′; reverse 5′-CGC AAT GTC CGG GAA ACC GCG GA-3′. The product was cloned into pCDH-CAM-MCS-EF1-CopGFP vector (YouBia company, Shanghai, China) to construct pCDH-CAM-MCS-EF1-CopGFP-NUSAP1. The positive overexpressed recombinant plasmid was sequenced by Berry Genomics Company and sequence alignment was carried out to screen successfully constructed overexpressed vector plasmid pCDH-CAM-MCS-EF1-CopGFP-NUSAP1.

Cell transfection

pCDH-CAM-MCS-EF1-CopGFP-NUSAP1 was transfected into MCF-7 using Lipofectamine 3000, and empty vector was used as the control. Simultaneously, si-NUSAP1 and corresponding Scramble sequence were transiently transfected MCF-7. Two days after transfection, some cells showed green fluorescence and were selected in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 100 g/ml Amp and 400 μg/ml G418 to obtain stable strains of NUSAP1 overexpression, incubated in DMEM (10% FBS + P.S.), and cryopreserved.

MTT assay

MCF-7 cells were made into single-cell suspension using medium with 10% FBS. A volume of 200 μL cell suspension was seeded into a 96-well plate, cultured for 24 h, then added with 10 μL MTT solution, and incubated for 4 h. We added 100 μL dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to each well and vibrated for 10 min of cell incubation at room temperature until the crystals were fully dissolved. Absorbance of each well was detected at 490 nm by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The result was recorded and a cell growth curve was drawn.

Transwell experiments

Migration and invasion experiments were performed in a 24-well Transwell device with a 12.0-μm polycarbonate membrane. For the migration experiment, the polycarbonate membrane in the upper chamber was not covered by Matrigel, which was contrary to the invasion experiment. The specific operational method was based on published articles [13]. The experimental installation for Transwell assay was purchased from Corning (Corning, NY, USA).

Cell cycle synchronization

To synchronize cells during the G0/G1 and G2/M transitions, MCF-7 cells were starved with 200 ng/ml nocodazole for 20 h or with serum for 48 h, then centrifuged and collected. Details are provided in previously published articles [14,15].

Flow cytometry

To analyze the effect of NUSAP1 on the cell cycle, si-NUSAP1 cells, scramble cells, and MCF-7 cells were cultured to a density of 5×105 cells/ml and processed using the CycleTEST Plus DNA kit (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). Briefly, at room temperature, all cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 400 g, incubated with 250 ml solution A (trypsin buffer) for 10 min, then incubated with 200 ml solution B (trypsin inhibitor and RNase) for 10 min, and incubated with 200 ml solution C (propidium iodide, PI) for 10 min in the dark. DNA content was determined using FACSCalibur (Becton-Dickinson) by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells in phase G2-M was analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA). To investigate the roles of NUSAP1 in cell apoptosis, the experiments were carried out using the FITC Annexin V kit (BD Bioscience, CA, USA). The synchronized cells were cultured for 24 h, centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 rpm, rinsed twice with precooled PBS, suspended into a density of 5×105 cells/ml with 400 μL binding buffer, kept in the dark at 2–8°C after adding 5 μL Annexin V-EGFP for 15 min of culture, and then adding 10 μL PI for 5 min of culture. Subsequently, flow cytometry was used for cell counting.

Statistical analysis

Measurement data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed by t test. The SD lines represent 3 independent repeated experiments. <0.05 indicates statistically significant differences. All graphs were drawn using GraphPad Pism7.

Results

Network-based meta-analysis

The data before and after treatment were analyzed and compared to screen out differentially expressed genes (DEGs). In brief, the conversion tool of Network Meta-analyst was used as the probe ID in chip data, and the corresponding platform was selected to convert the corresponding gene name. After probe matching, data were normalized using log2 conversion. Genes with adj p<0.01 and absolute value of log FC >1.5 were selected as DEGs (details of genes are provided in Supplementary Table 1).

Known IBC-related genes

IBC-related genes were downloaded from the ../../../../Documents/tencent files/1002826528/filerecv/the database for subsequent analysis and are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

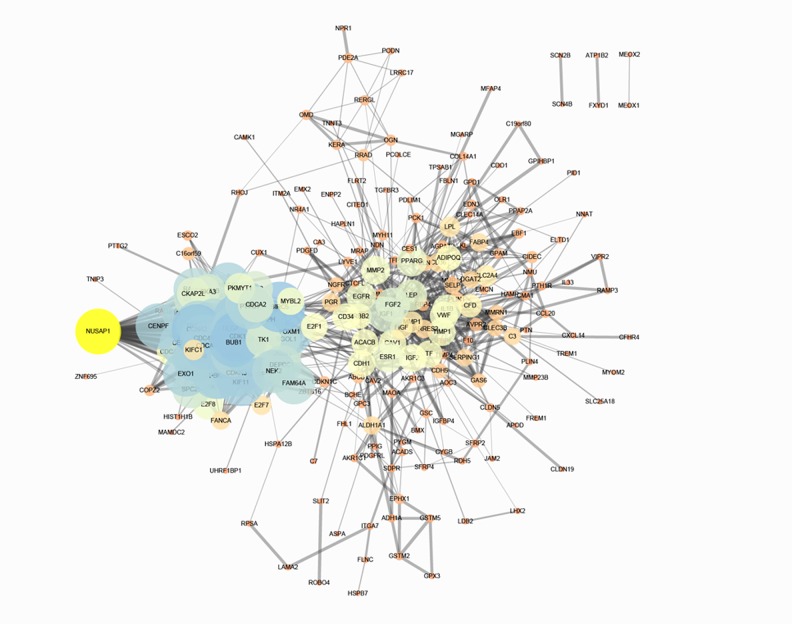

Interaction network of DEGs

The correlation between common research IBC genes and DEGs was identified using STRING (Figure 1), in which there were 355 links. Through reviewing the literature, NUSAP1 was selected for the following experiments.

Figure 1.

Protein-protein interaction network of IBC genes and DEGs. IBC-related genes were downloaded from PolySearch 2.0. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened from Network-based meta-analysis.

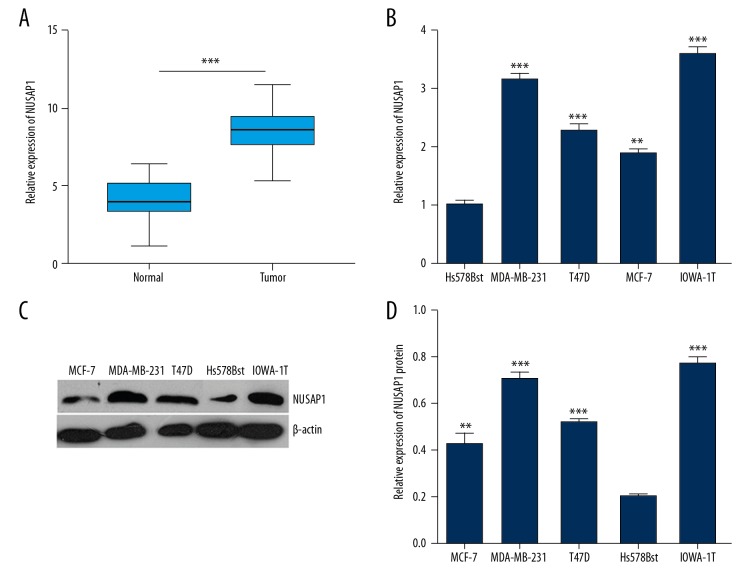

NUSAP1 was upregulated in IBC tissues and cells

T assess the NUSAP1 level in IBC, q-PCR and Western blotting assay was used for detecting the NUSAP1 level in IBC tissues and cells. The results showed that NUSAP1 presented higher expression in IBC tissues compared with the adjacent tissues. In cells, it was also upregulated in the breast cancer invasion cell lines compared with the normal human breast cell line (p<0.05; p<0.01; p<0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Expression of NUSAP1 in IBC clinical samples and breast cancer cells. (A) NUSAP1 presented high expression in IBC tissues compared with the adjacent tissues (P<0.001). (B) Expression of NUSAP1 was significantly higher in the 4 breast cancer cell lines compared with the normal Hs578Bst cell line (p<0.05, p<0.01). * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001. (C) Western blot analysis of expression of NUSAP1 in different breast cancer cell lines. (D) The bar chart below demonstrates the ratio of NUSAP1 protein to β-actin by densitometry in breast cancer cells. The data are mean ±SEM (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001 compared with control).

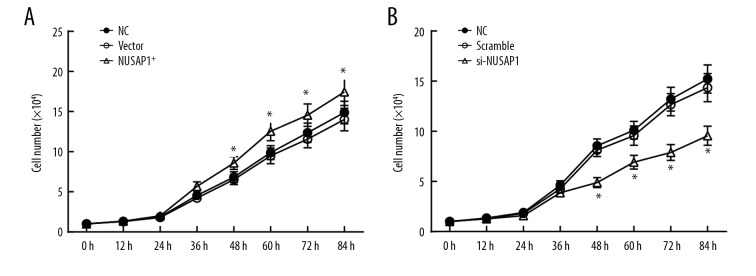

Effect of NUSAP1 on the proliferation of MCF-7 cells

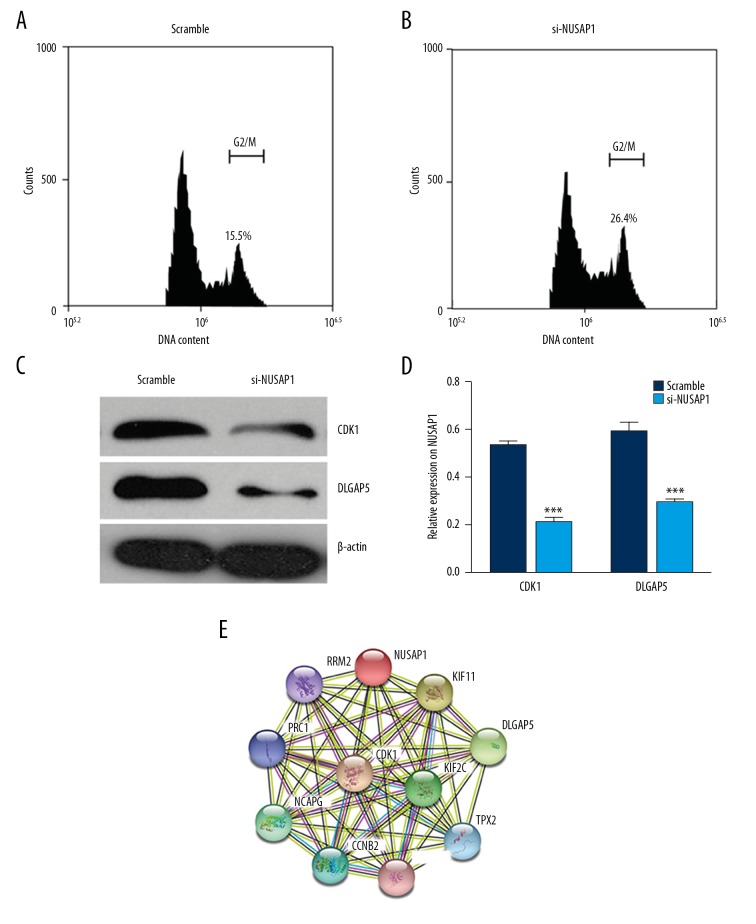

To investigate the role of NUSAP1 in IBC, we overexpressed or knocked down the expression of NUSAP1, and transfected it into MCF-7 cells. MTT and flow cytometry assays were performed to detected cell proliferation. The MTT assay results revealed that, from the 4th day of incubation, compared with empty vector-transfected cancer cells and non-transfected cancer cells, the number of cancer cells with NUSAP1 overexpression was slightly increased, as was cell proliferation (Figure 3A). Compared with the control group, the number of MCF-7 cells was notably decreased after NUSAP1 inhibition, in a time-dependent manner (p<0.05) (Figure 3B). Flow cytometry data showed that the percentage of si-NUSAP1 cells in phase G2/M (30.5%) was higher than that of scramble cells (20.8%) in phase G2/M (Figure 4A, 4B). Western blot showed that CDK1 and DLGAP5 was downregulated by si-NUSAP1 (Figure 4C, 4D). These results suggest that downregulation of NUSAP1 inhibited growth of MCF-7 cells.

Figure 3.

Effect of NUSAP1 on the proliferation of MCF-7 cells. MTT was used to detect the proliferation of cells. (A) Effect of NUSAP1 overexpression on the proliferation of MCF-7 cells. The number of cancer cells with NUSAP1 overexpression was slightly increased but did not reach a significant level. (B) Effect of si-NUSAP1 on the proliferation of MCF-7 cells. After inhibition of NUSAP1 expression, the number of MCF-7 cells was significantly decreased compared with the control group.

Figure 4.

NUSAP1 knockdown blocked cell cycle by suppressing the expression of CDK1 and DLGAP5. (A, B) Flow cytometry data showed that more cells were retarded in G2/M phase after 48-h transfection and the percentage of si-NUSAP1 cells in phase G2/M (26.4%) was higher than that of scramble cells (15.5%) in phase G2/M. (C) Western blot showed downregulated protein expression of CDK1 and DLGAP5. (D) The bar chart below demonstrates the ratio of CDK1 or DLGAP5 protein to β-actin by densitometry with or without NUSAP1 shRNA transfection. The data are mean ±SEM (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001). (E) Protein-protein interaction network of NUSAP1.

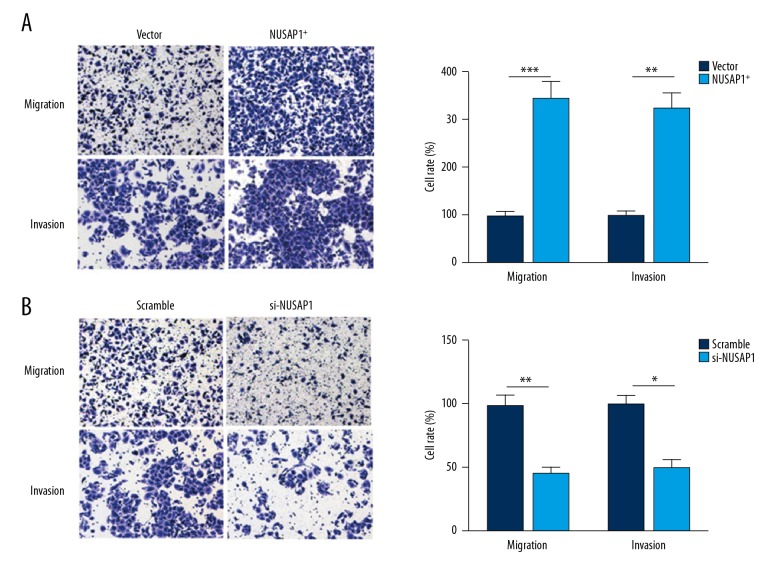

Effect of NUSAP1 on the migration and invasion of MCF-7 cells

To investigate the effect of NUSAP1 on IBC cell migration and invasion, cell migration and invasion assays were performed. In Transwell experiments, cell migration and invasion were increased in MCF-7 cells with NUSAP1 overexpression compared with the MCF-7 cells transfected with empty vector (p<0.05; p<0.01) and were obviously decreased in si-NUSAP1 cells compared with scramble cells (p<0.05; p<0.01) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of NUSAP1 on the migration and invasion of MCF-7 cells. (A) Images and statistical results from the Transwell migration and invasion assays of NUSAP1 overexpression MCF-7 cells (×100). (B) Images and statistical results from the Transwell migration and invasion assays of si-NUSAP1 MCF-7 cells (×100). * p<0.05; ** p<0.01.

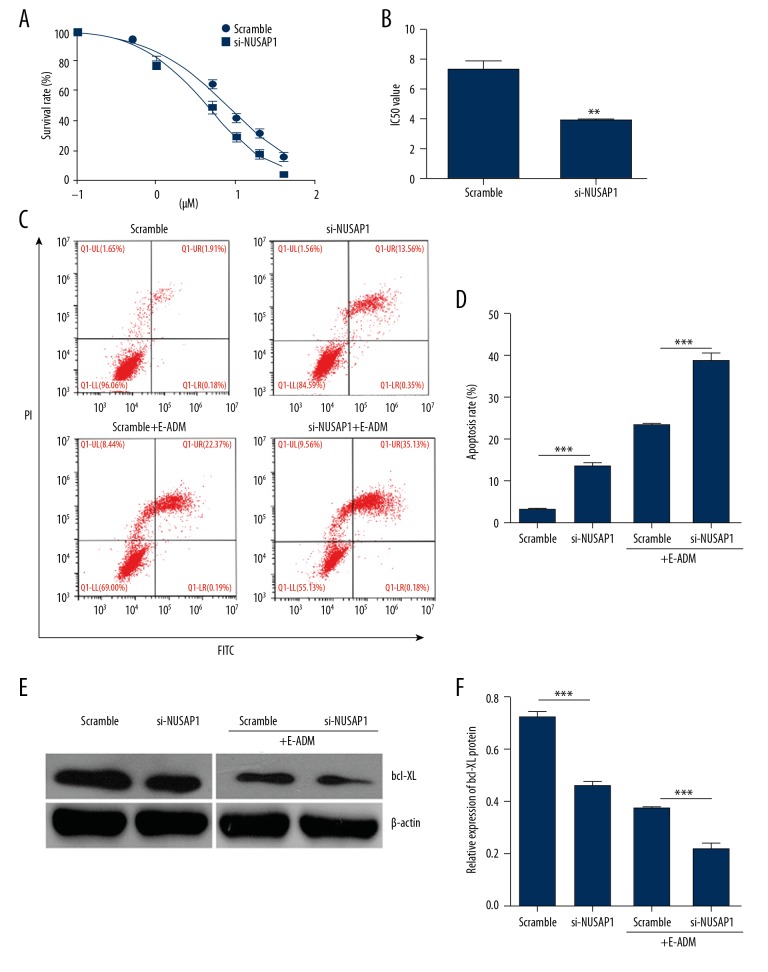

Inhibition of NUSAP1 expression remission epirubicin (E-ADM) resistance of MCF-7 cells

To assess the role of NUSAP1 in regulation E-ADM resistance, MTT assay was used to detected the survival rate of different E-ADMs (0.1–40 μM). MTT results showed that silencing NUSAP1 significantly inhibited cell growth and decreased IC50 value (si-NUSAP1 vs. control: 7.391 μM vs. 4.189 μM) (Figure 6A, 6B), which indicated that NUSAP1 reversed E-ADM resistance of MCF-7 cells. To further investigate the mechanism of NUSAP1 remission E-ADM resistance in MCF-7 cells, flow cytometry assay was performed in NUSAP1 silencing of MCF-7 cells with or without exposure to E-ADM (Figure 6C). Downregulating NUSAP1 dramatically promoted cell apoptosis in MCF-7 cells compared to control groups (Figure 6D, p<0.05; p<0.01) and the apoptosis rate further increased significantly in si-NUSAP1 cells treated with E-ADM (Figure 6D, p<0.001). In contrast, downregulation of NUSAP1 dramatically inhibited the protein expression of bcl-XL in MCF-7 cells with or without expose to E-ADM (Figure 6E, 6F, p<0.001), indicating that NUSAP1 inhibition improved the sensitivity of MCF-7 cells to E-ADM.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of NUSAP1 expression and E-ADM process promoted the apoptosis of MCF-7. (A) MTT assay was performed in scramble and NUSAP1 silencing cells exposed to E-ADM (0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 20, 40 μM). (B) IC50 value of E-ADM in MCF-7 cells with or without NUSAP1 silencing. (C) Annexin V-FITC/PI was used to detect the apoptosis of cells by flow cytometry. (D) Statistical results of total apoptosis rate were analyzed from 3 times experiments. Cell apoptosis rate=UR+LR. *p<0.05; **p<0.01. (E) Western blot showed downregulated protein expression of bcl-XL with or without E-ADM treatment and NUSAP1 shRNA transfection. (F) The bar chart below demonstrates the ratio of bal-Xl protein to β-actin by densitometry with or without E-ADM treatment and NUSAP1 shRNA transfection. The data are mean ±SEM (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001).

Discussion

Using molecular biology techniques to study the molecular mechanism of cancer has become a strong trend in cancer research. Before clinical verification, bioinformatics can be used to find and screen DEGs associated with tumorigenesis. Much related research work has focused on the extraction and classification of gene expression data by means of gene differential expression analysis. In 1999, cancers were first classified by monitoring gene expression based on DNA microarray, and a general strategy for the discovery and prediction of cancer classification for other types of cancer was proposed [16]. Since then, scientists have been able to mine potentially important genes in cancer by comparing the gene expression profiles of cancerous tissues and normal tissues. However, this approach is difficult to use for screening genes that play an important role in tumor expression, so meta-analysis is used to compare and evaluate the intersection of specific gene expression datasets for many cancers and to screen cancer-related genes [17]. In the present study, we screened the IBC-related gene NUSAP1 based on bioinformatics methods, and a PPI data network map between the DEGs from the GEO database and IBC-related genes from PolySearch 2.0 was constructed using analysis tools in STRING. The results demonstrated that, except for SCN4B, BIRC5, NUSAP1, and CDCA8, all genes were in this map and directly interacted with the IBC hot gene MKI67. Through reviewing relevant documents, NUSAP1 was selected as the study gene in subsequent experiments.

NUSAP1 is a 55-KD vertebrate protein that plays a key role in spindle assembly and normal cell cycle progression and has been shown to interact directly with microtubules [18]. NUSAP1 was first found in the study of melanoma, and identified to be pertinent to cell proliferation [10,11]. After that, NUSAP1 gradually became the focus in various tumor research. Brinkley found that spindle defects lead to genomic instability in invasive tumor cells with NUSAP1 loss [19]. Raemaekers found that NUSAP1 is localized in the nucleus and spindle and is over-expressed in proliferating cells in phase G2/M, resulting in spindle bundle bundling and inhibiting cell proliferation [18]. In 2011, NUSAP1 was identified as an overexpression marker gene in invasive carcinomas and was predicted as a new tumor marker (20). Other studies have revealed that high expression of the NUSAP1 gene is associated with the movement of neural crest cells and the invasion characteristics of prostate cancer cells in zebrafish [7,21]. Catherine found that NUSAP1 was beneficial for prostate cancer cell invasion and migration [22]. Through protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis, we found that NUSAP1 can interact with CDK1 and DLGAP5. In eukaryotes, the decreased CDK1 correlates with G2/M phase accumulation [23]. He et al. showed that knockdown of UBAP2L induces G2/M phase arrest in breast cancer cells by decreasing the expression of CDK1 [24]. DLGAP5 is a novel cell cycle-regulated gene that can inhibit the proliferation and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells [25], but its function in breast cancer cells is not clear.

The present study found that expression of the NUSAP1 gene in cancer tissues of IBC patients was remarkably higher than that in adjacent tissues, and knockdown of NUSAP1 inhibited the expression of CDK1 and DLGAP5. The migration and invasion ability of the IBC cell line was enhanced by NUSAP1 overexpression but was significantly reduced by NUSAP1 inhibition, indicating that NUSAP1 expression facilitates the migration and invasion of IBC cells. Many reports have shown a correlation between NUSAP1 overexpression and cell proliferation, cycle, invasion, and migration.

With the increasing number of women developing breast cancer worldwide, and more than 1 million of women dying from breast cancer each year, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is very important. In clinical practice, anthracyclines (such as epirubicin) and taxanes (such as docetaxel), combined with other drugs, were used for the treatment of breast cancer. For instance, patients with lymph-node-positive breast cancer take docetaxel after combined use of doxorubicin and cyclic ammonium phosphate [26], and patients with triple-negative breast cancer were treated by epirubicin combined with docetaxel [27]. The combined effect of taxane and Herceptin treatment is used for breast cancer therapy induced by the overexpression of HER2 [28–31]. Our investigation found that inhibition of the NUSAP1 gene significantly inhibited MCF-7 cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, and epirubicin treatment enhanced cell apoptosis. We conclude that therapy targeting the NUSAP1 gene is important for neoadjuvant chemotherapy in IBC.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study confirmed that knockdown of NUSAP1 inhibited proliferation, migration, and invasion of IBC cells and enhanced the chemosensitivity of IBC cells to epirubicin by inhibiting the expression of CDK1 and DLGAP5.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Table 1.

List of detailed genes selected by network-based meta-analysis in the study.

| Name | Name | Name | Name | Name | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGF1 | IGFBP4 | OLFML3 | ZBTB16 | COPZ2 | KERA |

| C19orf80 | SLC2A4 | ATP1B2 | FAM72D | ENPP2 | C2orf40 |

| VWF | OAF | MRAP | CDK1 | FOXM1 | TNIP3 |

| COL14A1 | FBLN1 | EXO1 | PTTG2 | DGAT2 | HJURP |

| NCAPH | MMP23B | OIP5 | CCL20 | KIF4A | C3 |

| PPAP2A | LPL | PLIN1 | IL33 | KL | RRAD |

| SDPR | KIF11 | HAPLN1 | PLK1 | EPHX1 | DMRT2 |

| CD36 | AKAP12 | RAD51 | PBK | CXCL14 | ATOH8 |

| FXYD1 | SCRN2 | AOC3 | SPAG5 | PDGFRL | TUSC5 |

| GDF10 | LAMA2 | C15orf42 | MME | KCNB1 | CLDN19 |

| RAD54L | SFRP4 | C1QTNF7 | MMRN1 | RDH5 | AQP7P2 |

| UHRF1 | MCM10 | CMA1 | ABLIM3 | MAOA | GSTM2 |

| TNNT3 | DARC | F10 | PCOLCE | CA4 | TPX2 |

| KIF23 | PRC1 | ESCO2 | HIST1H1B | G0S2 | CCNA2 |

| FAM64A | CD300LG | CES1 | TSHZ2 | ELTD1 | TSC22D3 |

| TGFBR3 | ALDH1A1 | TFPI | SAMD5 | CA3 | NUSAP1 |

| PDE2A | LEP | PTTG1 | C16orf89 | MMP11 | TMEM100 |

| ITIH5 | JAM2 | C1QTNF9B | LUZP2 | TIMP4 | FAM83D |

| FHL1 | MEOX2 | CENPA | ACACB | APOD | SERPING1 |

| AKR1C3 | ROBO4 | PHYHIP | CAV2 | ELN | EMX2 |

| CEP55 | LDB2 | GSC | PODN | PTN | FLNC |

| TROAP | THRSP | RPSA | NNAT | CAMK1 | PDLIM1 |

| DLGAP5 | C16orf59 | RERGL | MMP1 | FREM1 | PCK1 |

| HRC | CDCA8 | ZWINT | CFD | PAMR1 | CYP4F22 |

| CDCA5 | BLM | RBP4 | CENPE | AKR1C1 | FIGF |

| IGFBP6 | PPARG | CKS2 | OMD | HOXA5 | 1-Mar |

| TK1 | CD34 | SEMA3G | CKMT2 | ERCC6L | DEPDC1B |

| TSPAN7 | VWCE | DEPDC1 | ANGPTL1 | HABP4 | CCDC8 |

| ASPM | RDM1 | CYGB | PID1 | ZNF695 | ART5 |

| GPC3 | DPT | CPZ | AGPAT2 | ITGA7 | NMU |

| E2F1 | FAM54A | OGN | HSPB7 | PPP1R1A | LHX2 |

| POLQ | MATN2 | SCN2B | NPR1 | FABP4 | MYOM2 |

| CLDN5 | PLIN4 | ASPA | NDN | ACADS | SOX11 |

| HMMR | FANCA | ABCA8 | LOC100128164 | RARRES2 | CFHR4 |

| KIF2C | NGFR | SLIT2 | KIFC1 | MYZAP | TREM1 |

| CDKN1C | MAB21L1 | PTH1R | PDGFD | GIMAP7 | TTK |

| EMCN | CIDEC | MFAP4 | LRRC17 | MMP2 | LGALS12 |

| EZH2 | NEK2 | BMX | MYOC | GAS6 | PDZRN3 |

| IL11RA | OSR1 | H19 | MEOX1 | MELK | ANGPTL7 |

| HSPA12B | C7 | MAMDC2 | CDH5 | MYH11 | MYRIP |

| FLRT2 | RNASE4 | RHOJ | CENPF | DAAM2 | CITED1 |

| BTNL9 | TNMD | C4orf49 | C1orf115 | BOC | CDKN3 |

| SGOL1 | SKA3 | VIPR2 | C5orf46 | CMTM5 | TCEA2 |

| CLEC14A | EBF1 | CLEC3B | EBF3 | DENND2A | HLF |

| CCDC80 | CDO1 | CIDECP | GPX3 | TPO | BCHE |

| DTL | ABCA9 | DIO3OS | OLR1 | CRTAC1 | MIR143HG |

| SLC25A18 | ITM2A | E2F8 | CDC25C | EDN3 | ANLN |

| BIRC5 | SHE | RAMP3 | MYBL2 | TPSAB1 | MMP12 |

| ADIPOQ | IL1B | E2F7 | C18orf34 | HAMP | PEBP4 |

| GPD1 | GUCA2B | SPC25 | GPIHBP1 | LOC572558 | LYVE1 |

| CAV1 | PYGM | GSTM5 | PCDH12 | LOC100507537 | ANKRD29 |

| NCAPG | ADH1A | ABCB1 | KIF18A | IGF2 | 4-Sep |

| GPAM | ZCCHC24 | SRPX | CDCA2 | RSPO3 | GTSE1 |

| UBE2C | ADH1C | AVPR2 | CKAP2L | FGF2 | PLP1 |

| SCN4B | PKMYT1 | SELP | CPXM1 | TF | KIF20A |

| CDC45 | UBE2T | DNASE1L3 | CDCA3 | SFRP2 | BUB1 |

Supplementary Table 2.

IBC-related genes were downloaded from the../../../../Documents/tencent files/1002826528/filerecv/the database.

| Name | Name |

|---|---|

| ERBB2 | CD324 |

| EGFR | GFRP1 |

| ESR1 | PPIG |

| NR3C3 | RAD1 |

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Kalantari Khandani B, Tavakkoli L, Khanjani N. Metastasis and its related factors in female breast cancer patients in Kerman, Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18(6):1567–71. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.6.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li S, Fu H, Wang Y, et al. MicroRNA-101 regulates expression of the v-fos FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog (FOS) oncogene in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2009;49:1194–202. doi: 10.1002/hep.22757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayakawa T, Hata M, Kuwahara-Otani S, et al. Fine structure of interleukin 18 (IL-18) receptor-immunoreactive neurons in the retrosplenial cortex and its changes in IL18 knockout mice. J Chem Neuroanat. 2016;78:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iyer J, Moghe S, Furukawa M, Tsai MY. What’s Nu(SAP) in mitosis and cancer? Cell Signal. 2011;23:991–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L, Yang L, Qiao F, et al. High levels of nucleolar spindle-associated protein and reduced levels of BRCA1 expression predict poor prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang M, Yang D, Liu X, et al. [Expression of Nusap1 in the surgical margins of hepatocellular carcinoma and its association with early recurrence]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2013;33(6):937–38. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulzar ZG, McKenney JK, Brooks JD. Increased expression of NuSAP in recurrent prostate cancer is mediated by E2F1. Oncogene. 2013;32:70–77. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kokkinakis DM, Liu X, Neuner RD. Modulation of cell cycle and gene expression in pancreatic tumor cell lines by methionine deprivation (methionine stress): Implications to the therapy of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1338–48. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamoto A, Higo M, Shiiba M, et al. Down-regulation of nucleolar and spindle-associated protein 1 (NUSAP1) expression suppresses tumor and cell proliferation and enhances anti-tumor effect of paclitaxel in oral squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogunovic D, O’Neill DW, Belitskaya-Levy I, et al. Immune profile and mitotic index of metastatic melanoma lesions enhance clinical staging in predicting patient survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:20429–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905139106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryu B, Kim DS, Deluca AM, Alani RM. Comprehensive expression profiling of tumor cell lines identifies molecular signatures of melanoma progression. PLoS One. 2007;2:e594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marie SK, Okamoto OK, Uno M, et al. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase transcript abundance correlates with malignancy grade in human astrocytomas. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:807–15. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Q, Wu J, Wei P, et al. Overexpression of forkhead Box C2 promotes tumor metastasis and indicates poor prognosis in colon cancer via regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:2022–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz-Rodriguez E, Alvarez-Fernandez S, Chen X, et al. Deficient spindle assembly checkpoint in multiple myeloma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrero M, Ferragud J, Orlando L, et al. Phosphorylation of AIB1 at mitosis is regulated by CDK1/CYCLIN B. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raemaekers T, Ribbeck K, Beaudouin J, et al. NuSAP, a novel microtubule-associated protein involved in mitotic spindle organization. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:1017–29. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brinkley BR. Managing the centrosome numbers game: From chaos to stability in cancer cell division. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:18–21. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01872-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kretschmer C, Sterner-Kock A, Siedentopf F, et al. Identification of early molecular markers for breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:15. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yazilitas D, Sendur MA, Karaca H, et al. Efficacy of dose dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel versus conventional dose doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel or docetaxel in patients with node-positive breast cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:1471–77. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.4.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nie J, Wang H, He F, Huang H. Nusap1 is essential for neural crest cell migration in zebrafish. Protein Cell. 2010;1:259–66. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0036-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu L, Li XR, Hu YH, Zhang J. [Relevance between TOP2A, EGFR gene expression and efficacy of docetaxel plus epirubicin as neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple negative breast cancer patients]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2016;96:940–43. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2016.12.007. [in Chinese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon CA, Gong X, Ganesh D, Brooks JD. NUSAP1 promotes invasion and metastasis of prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:29935–50. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang WW, Tsai SC, Peng SF, et al. Kaempferol induces autophagy through AMPK and AKT signaling molecules and causes G2/M arrest via downregulation of CDK1/cyclin B in SK-HEP-1 human hepatic cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:2069–77. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He J, Chen Y, Cai L, et al. UBAP2L silencing inhibits cell proliferation and G2/M phase transition in breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2018;25:224–32. doi: 10.1007/s12282-017-0820-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao W, Liu W, Yuan Q, et al. Silencing of DLGAP5 by siRNA significantly inhibits the proliferation and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baselga J. Herceptin alone or in combination with chemotherapy in the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: pivotal trials. Oncology. 2001;61(Suppl 2):14–21. doi: 10.1159/000055397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merlin JL, Barberi-Heyob M, Bachmann N. In vitro comparative evaluation of trastuzumab (Herceptin) combined with paclitaxel (Taxol) or docetaxel (Taxotere) in HER2-expressing human breast cancer cell lines. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1743–48. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jandial DD, Krill LS, Chen L, et al. Induction of G2M arrest by flavokawain a, a kava chalcone, increases the responsiveness of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells to herceptin. Molecules. 2017;22(3) doi: 10.3390/molecules22030462. pii: E462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez-Ellis C, Goncalves A, Jacquemier J, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of trastuzumab (herceptin) in HER2-overexpressed metastatic breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32:492–98. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181931277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang T, Jiang ZF, Song ST, et al. [Herceptin as a single agent in patients with HER2 overexpressing metastatic breast cancer]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2004;26:430–32. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Q, Weng Z, Lu Y, et al. An experimental analysis of the molecular effects of trastuzumab (herceptin) and fulvestrant (falsodex), as single agents or in combination, on human HR+/HER2+ breast cancer cell lines and mouse tumor xenografts. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0168960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1.

List of detailed genes selected by network-based meta-analysis in the study.

| Name | Name | Name | Name | Name | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGF1 | IGFBP4 | OLFML3 | ZBTB16 | COPZ2 | KERA |

| C19orf80 | SLC2A4 | ATP1B2 | FAM72D | ENPP2 | C2orf40 |

| VWF | OAF | MRAP | CDK1 | FOXM1 | TNIP3 |

| COL14A1 | FBLN1 | EXO1 | PTTG2 | DGAT2 | HJURP |

| NCAPH | MMP23B | OIP5 | CCL20 | KIF4A | C3 |

| PPAP2A | LPL | PLIN1 | IL33 | KL | RRAD |

| SDPR | KIF11 | HAPLN1 | PLK1 | EPHX1 | DMRT2 |

| CD36 | AKAP12 | RAD51 | PBK | CXCL14 | ATOH8 |

| FXYD1 | SCRN2 | AOC3 | SPAG5 | PDGFRL | TUSC5 |

| GDF10 | LAMA2 | C15orf42 | MME | KCNB1 | CLDN19 |

| RAD54L | SFRP4 | C1QTNF7 | MMRN1 | RDH5 | AQP7P2 |

| UHRF1 | MCM10 | CMA1 | ABLIM3 | MAOA | GSTM2 |

| TNNT3 | DARC | F10 | PCOLCE | CA4 | TPX2 |

| KIF23 | PRC1 | ESCO2 | HIST1H1B | G0S2 | CCNA2 |

| FAM64A | CD300LG | CES1 | TSHZ2 | ELTD1 | TSC22D3 |

| TGFBR3 | ALDH1A1 | TFPI | SAMD5 | CA3 | NUSAP1 |

| PDE2A | LEP | PTTG1 | C16orf89 | MMP11 | TMEM100 |

| ITIH5 | JAM2 | C1QTNF9B | LUZP2 | TIMP4 | FAM83D |

| FHL1 | MEOX2 | CENPA | ACACB | APOD | SERPING1 |

| AKR1C3 | ROBO4 | PHYHIP | CAV2 | ELN | EMX2 |

| CEP55 | LDB2 | GSC | PODN | PTN | FLNC |

| TROAP | THRSP | RPSA | NNAT | CAMK1 | PDLIM1 |

| DLGAP5 | C16orf59 | RERGL | MMP1 | FREM1 | PCK1 |

| HRC | CDCA8 | ZWINT | CFD | PAMR1 | CYP4F22 |

| CDCA5 | BLM | RBP4 | CENPE | AKR1C1 | FIGF |

| IGFBP6 | PPARG | CKS2 | OMD | HOXA5 | 1-Mar |

| TK1 | CD34 | SEMA3G | CKMT2 | ERCC6L | DEPDC1B |

| TSPAN7 | VWCE | DEPDC1 | ANGPTL1 | HABP4 | CCDC8 |

| ASPM | RDM1 | CYGB | PID1 | ZNF695 | ART5 |

| GPC3 | DPT | CPZ | AGPAT2 | ITGA7 | NMU |

| E2F1 | FAM54A | OGN | HSPB7 | PPP1R1A | LHX2 |

| POLQ | MATN2 | SCN2B | NPR1 | FABP4 | MYOM2 |

| CLDN5 | PLIN4 | ASPA | NDN | ACADS | SOX11 |

| HMMR | FANCA | ABCA8 | LOC100128164 | RARRES2 | CFHR4 |

| KIF2C | NGFR | SLIT2 | KIFC1 | MYZAP | TREM1 |

| CDKN1C | MAB21L1 | PTH1R | PDGFD | GIMAP7 | TTK |

| EMCN | CIDEC | MFAP4 | LRRC17 | MMP2 | LGALS12 |

| EZH2 | NEK2 | BMX | MYOC | GAS6 | PDZRN3 |

| IL11RA | OSR1 | H19 | MEOX1 | MELK | ANGPTL7 |

| HSPA12B | C7 | MAMDC2 | CDH5 | MYH11 | MYRIP |

| FLRT2 | RNASE4 | RHOJ | CENPF | DAAM2 | CITED1 |

| BTNL9 | TNMD | C4orf49 | C1orf115 | BOC | CDKN3 |

| SGOL1 | SKA3 | VIPR2 | C5orf46 | CMTM5 | TCEA2 |

| CLEC14A | EBF1 | CLEC3B | EBF3 | DENND2A | HLF |

| CCDC80 | CDO1 | CIDECP | GPX3 | TPO | BCHE |

| DTL | ABCA9 | DIO3OS | OLR1 | CRTAC1 | MIR143HG |

| SLC25A18 | ITM2A | E2F8 | CDC25C | EDN3 | ANLN |

| BIRC5 | SHE | RAMP3 | MYBL2 | TPSAB1 | MMP12 |

| ADIPOQ | IL1B | E2F7 | C18orf34 | HAMP | PEBP4 |

| GPD1 | GUCA2B | SPC25 | GPIHBP1 | LOC572558 | LYVE1 |

| CAV1 | PYGM | GSTM5 | PCDH12 | LOC100507537 | ANKRD29 |

| NCAPG | ADH1A | ABCB1 | KIF18A | IGF2 | 4-Sep |

| GPAM | ZCCHC24 | SRPX | CDCA2 | RSPO3 | GTSE1 |

| UBE2C | ADH1C | AVPR2 | CKAP2L | FGF2 | PLP1 |

| SCN4B | PKMYT1 | SELP | CPXM1 | TF | KIF20A |

| CDC45 | UBE2T | DNASE1L3 | CDCA3 | SFRP2 | BUB1 |

Supplementary Table 2.

IBC-related genes were downloaded from the../../../../Documents/tencent files/1002826528/filerecv/the database.

| Name | Name |

|---|---|

| ERBB2 | CD324 |

| EGFR | GFRP1 |

| ESR1 | PPIG |

| NR3C3 | RAD1 |