Abstract

Background

Continuing professional development (CPD) in healthcare is fundamental for making sure frontline staff practice safely and effectively. This requires practitioners to update knowledge and skills regularly to match the changing complexity of healthcare needs. The drive towards using limited resources effectively for service improvements and the need for a flexible workforce necessitate a review of ad hoc approaches to CPD.

Objective

To develop strategies for achieving effective CPD in healthcare.

Design

A case study design drawing on principles of realist synthesis was used during two phases of the study to identify and test what works and in what circumstances.

Setting

One National Health Service Trust in South East England.

Participants

CPD stakeholders including professional regulatory bodies (n = 8), commissioners of healthcare (n = 15), facilitators of clinical skills development (n = 34), NHS staff in clinical leadership positions (n = 38), NHS staff undertaking skills development post graduate programs (n = 31), service user advocates (n = 8) and an international expert reference group (ERG) (n = 10).

Methods

Data sources included a review of scholarly and grey literature, an online survey and a consensus workshop. Thematic and content analyses were used during data processing.

Results

The findings present four interdependent transformation theories comprising transforming individual practice, skills for the changing healthcare contexts, knowledge translation and workplace cultures to optimize learning, development and healthcare performance.

Conclusions

The transformation theories contextualize CPD drivers and identify conditions conducive for effective CPD. Practitioner driven CPD in healthcare is effective within supportive organizations, facilitated workplace learning and effective workplace cultures. Organizations and teams with shared values and purpose enable active generation of knowledge from practice and the use of different types of knowledge for service improvements.

Keywords: Continuing professional development, Realist synthesis, Education, Case study, Transformation theories, Workplace learning

1. Background

Continuing professional development (CPD) in healthcare is fundamental for enabling practitioners to acquire and apply skills relevant for sustaining person-centered, safe and effective care. This entails practitioners engaging in regular skills renewal to match changes in healthcare needs and their complexity, new models of delivering care and public expectations (Filipe et al., 2014). However, the drive towards using limited resources effectively for service improvements and the critical need for a more flexible workforce require revisiting ad hoc approaches to CPD (Gibbs, 2011).

1.1. What is CPD?

Continuing professional development is used synonymously with other terms such as continuing professional education, lifelong learning and staff development (Gallagher, 2007). Billett (2002) distinctively observed that definitions for activity associated with learning in the workplace tend to focus on individual objectives, yet the goals of CPD are mutually interdependent on individual and system aspects. Madden and Mitchell (1993, p.12) conceived a more indicative definition of CPD being “the maintenance and enhancement of the knowledge, expertise and competence of professionals throughout their careers according to a plan formulated with regard to the needs of the professional, the employer, the professions and society”. While inclusive of multiple CPD stakeholders, the definition assumes a reductionist needs-led perspective rather than a proactive approach that incorporates complexities of CPD and a vision for an effective and skilful workforce.

Our study employed the Executive Agency for Health Consumers (EAHC) definition of CPD being the “systematic maintenance, improvement and continuous acquisition and/or reinforcement of the life-long knowledge, skills and competences of health professionals. It is pivotal to meeting patient, health service delivery and individual professional learning needs. The term acknowledges not only the wide ranging competences needed to practice high quality care delivery but also the multi-disciplinary context of patient care” (EAHC, 2013, p. 6). This definition includes patient relationship skills, regulatory and ethical developments as well as research and interprofessional collaboration.

Draper and Clark (2007) identified the urgency for a convincing evidence base to illustrate that CPD achieves what it seeks to impart. Evidence about CPD effectiveness is still limited as practitioners themselves are often unable to articulate the impact of their CPD activity, which undermines confidence in the value of investing in CPD (Moriarty and Manthorpe, 2014). Effectiveness of training substantiates its value (Moss et al., 2016). It is thus crucial to understand what effective CPD is to get an insight into its worth.

1.2. What is Effective CPD in Healthcare?

Effectiveness documents achievement of intended outcomes. However, using an outcome-based approach to assess the effectiveness of CPD is a narrow way of understanding its impact (Wallace and May, 2016). The outcome-based method does not take into account the numerous factors that may influence practitioners' CPD activity. For example, in their assessment of the impact of CPD activities on healthcare professionals' clinical practice, Légaré et al. (2017) built on subjective reports of intention to change behaviour to denote effective CPD. This approach does not distinguish factors that may affect practitioners' learning and actual behavioural change in the workplace. Arguably, CPD evaluations ought to encompass stakeholders' interests in practitioners' CPD activity to answer the key concern of ‘who is CPD effective for?’ (Michalski and Cousins, 2000).

Mulvery (2013)'s contention that key CPD stakeholders comprise the individual practitioner, professional body and the organization is problematic. Professional bodies require practitioners to undertake CPD to demonstrate appropriate governance of maintaining professional standards (Mulvey, 2013). But, the mandatory nature of CPD for professional revalidation and limited persuasion to establish its impact loosely attaches the professional body to the key stakeholder triad (Ibrahim, 2015). Practitioners keep their CPD up to date to enhance employability and to retain innate job satisfaction and self-confidence (Bhatnagar and Srivastava, 2012). On the other hand, employers invest in practitioners' CPD with the hope that care will be delivered safely and effectively to minimize costs. However, evaluation of effectiveness of training is rarely considered alongside returns on investing in training activities (Moss et al., 2016).

The public, policy makers and educators each have interests aligned to the overall CPD purpose of person centered, safe and effective care (Mulvey, 2013). Despite the complex CPD stakeholder composition, healthcare practitioners' authentic learning and fitness to practice symbolize effective CPD (Schostak et al., 2010). Authentic learning holistically reflects the practitioner's scope of practice. This entails processes and conditions that underpin or are underpinned by learning, which may exceed the capacity for quantitative measures (Illeris, 2009).

1.3. How is Effective CPD Measured?

Continuing professional development is usually linked to outcomes such as improved quality of care and staff retention within organizations (Price and Reichert, 2017). Nonetheless, assessment of the impact of CPD rarely goes beyond measurements for satisfaction with training delivery (Carpenter, 2011). This implies the link between patient experience and outcomes is perchance but not adequately verified (Roessger, 2015). For example, a review of the impact of CPD on nurses' knowledge and confidence in the delivery of palliative care in rural areas yielded scant evidence that also lacked precision (Phillips et al., 2012). For the most part, the gap in unambiguous evidence of the impact of CPD is attributed to methodological challenges in verifying the direct association between CPD and healthcare outcomes (Draper and Clark, 2007). Moss et al. (2016) suggest the evaluation of effectiveness of training activities requires a comprehensive organizational strategy to enable measurement of outcomes, performance and the overall return on investing in training. However, it is also essential to have adequate understanding of the purpose of training and how to achieve intended improvements to support meaningful evaluation of worth for finite funding (Moore et al., 2015).

1.4. Aim of the Study

Our study aimed to develop strategies for achieving effective CPD for contemporary healthcare, using realist synthesis to explore relationships that explain what works for whom and in what circumstances (Pawson et al., 2004).

2. Methods

2.1. Design

A case study design was chosen to develop strategies for achieving effective CPD to sustain the overall goal of person centered, safe and effective care. We employed an embedded case study design (Yin, 2003) to reflect the numerous variables that influence healthcare practitioners' CPD activity. We used philosophies of realist synthesis, a theory driven process for understanding what works for whom and how (Pawson et al., 2004). The realist synthesis approach bridges the rift between assumed ease of identifying factors that cause change and the practical challenges of recognizing change in frontline practice (Greenhalgh et al., 2009). The healthcare practitioner locates in social realities of the workplace and organizational contexts, which are both relevant for professional practice, but also may influence CPD activity and implementation of new skills in practice. This follows the argument that contemporary learning goes beyond obtaining knowledge and skills to incorporate processes that result in faculty change (Illeris, 2009). Realist synthesis pursues a generative approach to explaining relationships about components that may produce change and the conditions pertinent to the functioning of these components (Pawson et al., 2004).

The study involved two phases to answer the overarching research question of ‘what mechanisms in what contexts would generate what desirable CPD outcomes?’ Mechanisms in this respect refer to particular aspects about CPD activity that generate results. Context explains characteristics of conditions in which CPD activity is hosted that are significant to the functioning of mechanisms. Outcomes constitute both intended and unintended results emanating from introducing different mechanisms in different contexts (Pawson and Tilley, 2004). The first phase focused on developing a conceptual framework to clarify CPD drivers in healthcare and tentative propositions. Tentative propositions explained preliminary theoretical strategies of achieving CPD effectiveness (Whetten, 1989). Phase two of the study aimed to test and refine the theoretical strategies.

2.2. Setting and Participants

The study involved CPD stakeholders in South East England and an expert reference group (ERG) recruited to validate outputs. We purposively selected consenting individuals that research and publish widely on CPD to constitute the expert reference group (n = 10). These included representatives from academic and professional settings in England (n = 7) and Australia (n = 3).

Information about the study was promoted both verbally and electronically through local university lecturers for skills development modules and workplace mentors in one NHS Trust in South East of England. These were settings that potential participants worked in and funded, undertook or delivered CPD activity. Ninety-five (n = 95) participants completed the online CPD stakeholders' survey. They comprised representatives from professional regulatory bodies (n = 8), commissioners of healthcare services (n = 15), local university leads for clinical skills development programs (n = 6), NHS staff in clinical leadership positions (n = 38), NHS staff undertaking skills development post graduate programs (n = 20) and service user advocates (n = 8).

The consensus workshop engaged two stakeholder groups that we considered capable of challenging the conceptualization of context (C), mechanisms (M), outcomes (O) (CMO) relationships for effective CPD. Mentors of work-based skills development in the participating NHS Trust (n = 28) and NHS staff undertaking post graduate skills development courses within local universities (n = 11) participated in the consensus workshop.

2.3. Data Collection

Realist synthesis facilitates use of multiple sources of data to investigate processes and impact of interventions (Pawson et al., 2004). Data were collected from sources including a literature review, an online survey and a stakeholder workshop.

The review systematically examined grey and scholarly literature published from January 2006 to June 2014 in healthcare, human resource management and organizational development and social care. The literature review also entailed extrapolation from educational theories to inform the development of the conceptual and theoretical frameworks. The review aimed to answer three key questions:

-

•

What is CPD and why is it important?

-

•

What is the purpose and impact of CPD?

-

•

How do you facilitate and judge the effectiveness of CPD?

The literature review was aimed to generate insights about CPD activity and guide empirical data collection for refining propositions relating to practitioners' CPD. We consulted the ERG about references, content of the literature review and the draft CPD conceptual framework for achieving person centered, safe and effective care.

The second phase of the study included collecting empirical data. Pawson and Tilley (1997) postulate that drawing on stakeholders' invaluable knowledge and experience of what works, how and for whom enables validation and refinement of theory. The online survey targeted six stakeholder groups to test the practical application of the emerging CPD theoretical framework and theoretical prepositions. Open-ended questions invited stakeholders to provide information about CPD drivers, intended outcomes and methods for assessing effectiveness of learning in their organizations. The survey provided opportunity to service user advocates to comment on possible CPD stimuluses and how the impact of healthcare professionals' CPD would be recognized.

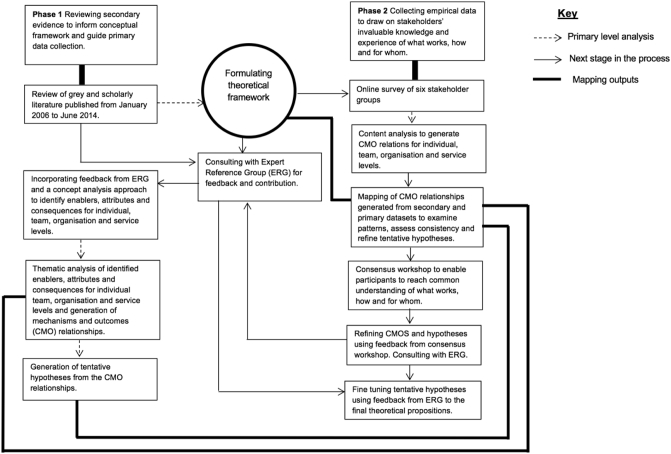

The study principal investigator facilitated the consensus workshop to enable participants to reach common understanding of strategies for achieving effective CPD. The consensus workshop invited participants to provide feedback on the theoretical framework and tentative propositions for effective CPD strategies in relation to their experiences. The facilitator supported participants to jointly discuss and resolve variances on the feedback forms. We consulted the ERG again to comment on the refined propositions. Fig. 1 illustrates the process of data collection and analysis during two stages of the study.

Fig. 1.

Process of data collection and analysis.

2.4. Analysis

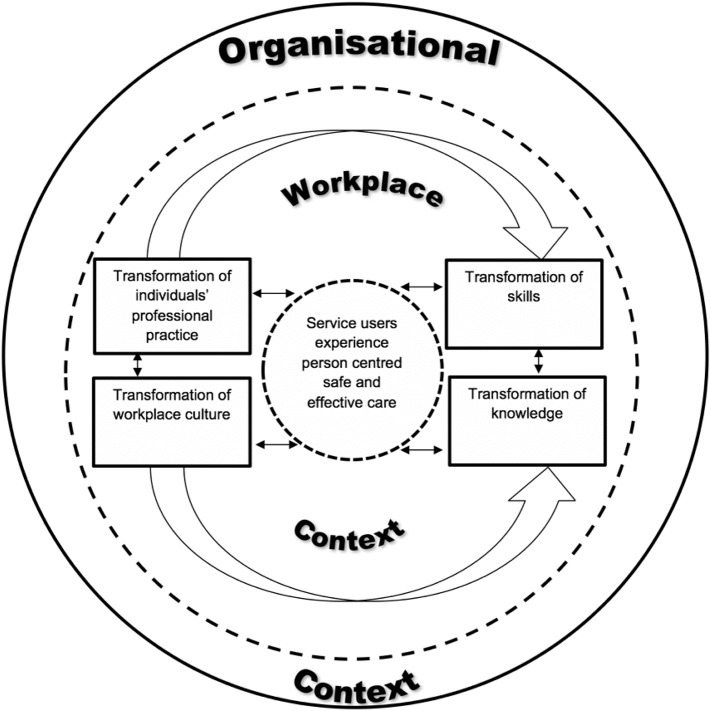

The individual practitioner constituted the unit of analysis embedded within sub units of teams and organizational contexts with a shared purpose of delivering person centered, safe and effective care. We examined the literature to identify CPD drivers and draw on educational philosophies to develop a conceptual framework (Fig. 2) for further data analysis and generation of CMO relationships. We used a concept analysis approach to develop understanding of the concept of effective CPD from the literature. The concept analysis approach clarifies concepts to guide their implementation in practice and evaluation of components and the relationships between them (Rodgers, 2000). The process entailed extracting for each of the units of analysis, defining characteristics of effective CPD; factors required for CPD effectiveness to happen; and events that would occur due to CPD effectiveness. Data extracted from the literature were themed to facilitate the generation of CMO relationships for effective CPD. The conceptual framework (Fig. 2) provided an analytical tool for systematically comparing themes and formulating tentative propositions about CMOs for effective CPD.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual framework illustrating CPD drivers and the relationships between them.

The framework illustrates CPD influences for the individual practitioner and teams in healthcare practice. The size and direction of the arrows illustrate the relationships that complete the learning process.

Data from the online survey were analyzed using a content analysis approach. Content analysis facilitates in depth understanding of the perspective of data to test theory (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). We devised three overarching categories that accommodated the most frequently appearing responses. Data were then grouped into the three categories including ‘what CPD should be’, ‘what CPD should do’ and ‘how to evidence effective CPD’. We themed the grouped data and identified frequencies for reoccurring themes. Commonly occurring themes were examined for patterns and the relationships between them to distinguish mechanisms for effective CPD, the contexts in which it happens and outcomes when CPD is effective.

These CMO relationships were logically compared with those generated from phase one to match patterns, assess consistency and to systematically strengthen the tentative propositions. The themes with highest frequencies were useful in distinguishing strongest and conceivable explanations of identified patterns (Pawson and Tilley, 1997). We used qualitative comments from the consensus workshop to refine CMO relationships and propositions generated about effective CPD. Written comments from the ERG were also useful in fine tuning and validating final outputs of the study.

2.5. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study obtained ethical clearance from the University's Research Ethics and Governance Committee ref. 13/H&SC/CL67. All participants volunteered to take part in the study and each participant gave informed written consent. Information given in the online survey indicated that participants' decisions to continue with completing the survey was formal consent for their participation. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time if they wished to do so without giving explanations.

3. Results

3.1. The Literature Review

The review illustrated the complexity of CPD and highlighted differences in practices, terminology and approach across various disciplines and countries. The review showed that there is considerable variance in CPD activity with mandatory and voluntary systems and formal and informal delivery of CPD existing alongside each other in some settings. Accreditation methods were also diverse and reflected different professional and educational values. We found a relative dearth of evidence about the impact of CPD on healthcare outcomes and professional practice.

Examining CPD drivers and educational philosophies in the literature facilitated the development of a conceptual framework (Fig. 2) that guided understanding of key CPD components and theory development about its effectiveness. We identified that areas for CPD transformations are interdependent, but some may require focus before others to achieve full benefit in the workplace and optimal organizational performance.

3.2. Theoretical Framework for Effective CPD

The study resulted in four overarching theoretical strategies for attaining maximum benefit from CPD activity. Table 1 presents the theoretical framework for effective CPD. We refer to the strategies as CPD transformation theories to represent a noticeable change resulting from the contribution of effective CPD to intended improvements in healthcare. A noticeable change illustrates improvements at the individual, team, organizational and service/society levels, reflective of the underlying purpose for the practitioner's CPD activity. For example a practitioner's improved skill in the assessment and diagnosis of dementia as a result of CPD may lead to improved team efficiency, lower costs of service delivery and patient experience of seamless care. The propositions presented explain CMO relationships that form CPD transformation theories. The transformation theories contribute interdependently to achieving the overall purpose of CPD on the premise that the workplace is the main resource for leaning and development.

Table 1.

A theoretical framework illustrating the context, mechanism and outcome (CMO) relationships that would facilitate effective accomplishment of identified purposes of CPD. The CMO relationships inform the theoretical inferences about effective CPD strategies. The CMO components appear in a linear way for ease of comprehension.

| Context (C) | Mechanism (M) | Outcome (O) |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Transformation of individual's professional practice | ||

|

Workplace context: C1 Opportunities for CPD that are work based C2 Culture of inquiry, learning and implementation Organizational context: C3 Supportive organizations that value work based learning & development |

M1 Facilitated support and reflection M2 Developing skill in reflection and self-awareness M3 Self-assessment M4 Learning that is self-driven |

For the individual: O1 Increased self-awareness O2 Increased self-confidence, and perceived self-efficacy O3 Transformational learning, new knowledge, & continuing motivation to learn O4 Empowerment, self-sufficiency and self-directing For the individual's role O5. Person centered safe & compassionate practice O6. Role clarity & opportunities for role innovation and development O7·Career progression O8. Meaningful positive engagement with change |

| 1.2 Transformation of skills to meet society's changing healthcare needs | ||

|

Workplace context: C4 A focus on team competences and effectiveness rather than just the individual Organizational context: C5 Value for money in the use of human resources and investment Healthcare context: C6 The need for staff in contemporary healthcare to be adaptable and flexible in responding to changing healthcare needs |

M5 Assessment of systems and team skills and competences M6 Identifying gaps in systems & service needs M7 Expanding & maintaining skills and competences through a range of different ways M8 Developing team effectiveness |

For service users: O9 Improved continuity and consistency experienced by service users For individual/team: O10 Better and sustained employability O11 Career progression O12 An effective cohesive team For the organization/system O13 Better integration of services O14 Better partnerships with services and agencies O15 Better value for money through effective use of human resources e.g. substitution and reduced duplication |

| 1.3 Transformation that enables knowledge translation | ||

|

Workplace context: C7 Engaging with and using different types of knowledge in everyday practice C8 Active sharing of knowledge in the workplace |

M9 Helping people to reflect on the quality and range of knowledge they use in practice M10 Blending different types of knowledge to guide practice M11 Facilitating dialogue about using knowledge in practice M12 Facilitating active inquiry and evaluation of own and collective practice and learning M13 Developing practical and theoretical knowledge of leadership, facilitation, evaluation and cultural aspects influencing knowledge translation in practice |

Workplace/team O16 Knowledge used in and developed from practice O17 A knowledge-rich culture Team & organizational O18 Active contribution to practice development O19 Innovation & creativity |

| 1.4 Transformation of work place culture to implement workplace and organizational values and purpose relating to person centered, safe and effective care | ||

|

C5 Context has explicit shared values and purposes C6 Organizational readiness to change |

M14 Developing shared values and a shared purpose M15 Facilitating the implementation of shared values through feedback, critical reflection, peer support and challenge M16 Evaluating experiences of shared values relating to person centered, safe and effective care from both service users and staff M17 Creating a culture that enables personal growth, effective relationships and team work M18 Developing leadership behaviors |

Service users: O20 Improved service user and provider experiences, outcomes and impact Staff/team: O21 Sustained person centered, safe and effective workplace culture O12 An effective cohesive team Organizational: O22 Increased employee commitment to work and learning O23 Organizational leadership and human behaviors O24 Increased organizational effectiveness |

3.2.1. Theory 1: Transformation of Individual's Professional Practice

Table 1.1 highlights the CMO relationships for transforming the individual's professional practice through CPD. The workplace and organization present contextual influences on CPD content, the value attached to the workplace as a learning resource and how the workplace is used to enable practice improvements. The theory of transforming individual professional practice infers:

Work based CPD built on learner driven assessment and self-awareness within a supportive organization and facilitated reflection enhances role clarity, opportunities for role development and engagement with meaningful change.

Transforming the individual's professional practice embraces aspects of other transformation theories to incorporate collective effect on the team and organization in understanding contributions to service improvements.

3.2.2. Theory 2: Transformation of Skills to Meet Society's Changing Healthcare Needs

Contextual factors in Table 1.2 emphasize a team approach to developing competences. The supposition is that no one person can deliver all the competences and skills required to support effective healthcare. Effective use of human resources and flexible ways of working provide the immediate context for CPD focus. The deductions for skills transformation emphasize a holistic approach to developing the full skillset required for efficient teams in healthcare. The propositions generated posit that:

Assessments for gaps in systems and team skills inform CPD for transforming skills to match society's changing healthcare needs.

Transforming skills impacts on service user experiences, team effectiveness, career progression opportunities and organizational partnerships.

3.2.3. Theory 3: Transformation of Knowledge to Enable Knowledge Translation

The third transformation theory focuses on knowledge, its uptake and use in practice. We conceptualized knowledge translation as a process of analyzing sharing and ethically applying knowledge for safe, person centered and effective care. Table 1.3 illustrates CMO relationships of how knowledge is used through approaches that subsequently benefit service users, teams and organizations. The mechanisms through which these outcomes arise relate to three levels of activity.

-

•

The first level focuses on everyday decisions that inform professional practice, reflecting on the quality and range of knowledge used in blending different types of knowledge to guide practice.

-

•

The second level emphasizes the facilitation skillset required across workplace teams to enable others to use knowledge through active inquiry and evaluation of their own and collective learning and professional practice.

-

•

The third level is more sophisticated because it concerns developing practical and theoretical knowledge about contextual factors that influence knowledge translation in practice specifically leadership, facilitation, evaluation and cultural aspects.

The resulting propositions for knowledge translation are:

A workplace that engages in active sharing and using different types of knowledge in practice blends various knowledge types to inform professional decision making and fosters skill in facilitating inquiry, evaluation of practice and leadership.

Effective transformation of knowledge generates knowledge rich cultures and active contribution to practice development, innovation and creativity.

3.2.4. Theory 4: Transformation of Workplace Culture to Implement Workplace and Organizational Values and Purpose

The fourth transformation theory focuses on CPD that addresses the immediate workplace culture and implementation of shared values across the organization and the health economy (Table 1.4). The CMO relationships acknowledge the need for an organization that upholds change with plans for ongoing improvements and the capacity to maintain the change. The proposition for the theory about transforming workplace culture through CPD is that:

Organizations that are ready to change promote development and implementation of shared values to enhance patient experiences, team cohesiveness, effectiveness in workplace cultures and organizational leadership.

4. Discussion

The current study draws on educational philosophies to underline CPD drivers and to convey strategies for achieving effective CPD in the workplace and organizational contexts. This is aligned to the notion that CPD in the workplace yields maximum benefit for knowledge translation through practice opportunities. The theoretical strategies illustrate direct benefit to individual practitioners, teams, the organization and ultimately service users. The transformation theories address concerns about the value of investing in CPD by illuminating outcomes of effective CPD and means of achieving them.

The findings highlight that the transformation of the individual's professional practice, which has direct effect on teams, the organization and service thrives within supportive organizations that value the workplace as a learning resource. Draper et al. (2016) note the role of organizational leadership in supporting CPD processes in complex environments but they do not provide the skillset required to match transforming professional practice to organizational priorities. Manley et al. (2016) contend leaders with clinical skills offer more workplace learning opportunities because they understand care pathways and have a range of skills to enable culture change, evaluation of care and continuous service improvement.

Regular assessments of healthcare service needs, system and team skills produce evidence about the requirements for organizational competence and team effectiveness. However, CPD activity aimed to equip practitioners with skills necessary to close identified gaps is dependent on successful knowledge translation in the workplace, assuming practitioners value the use of different types of knowledge necessary to improve practice (Rycroft-Malone, 2004). Successful transformation of skills ascertains that practitioners are to deliver care flexibly to suit the eclectic service needs. Skilled facilitators with expertise in relevant fields support knowledge translation for evidence-based healthcare (Martin and Manley, 2018). Facilitation of learning in the workplace emphasizes team competence and holistically creates opportunities for dialogue about the quality of knowledge used in practice and active sharing and implementation of different types of knowledge (Macfarlane et al., 2011). Workplace facilitation aims to grow collaborative relationships amongst frontline practitioners, which encourage positive workplace cultures and engagement with different types of knowledge (Watling, 2015).

Practitioners' CPD facilitated in a context of shared values and a clear indication of organizational readiness to adopt innovative ways of working bring about team cohesiveness and sustainable effective workplace cultures (Kinley et al., 2014). An effective workplace culture emphasizes person centered and collaborative relationships that draw as much on individuals' strengths as maximizing their potential for development (Manley et al., 2011). For many healthcare practitioners, personal motivation, peer support and mutual learning play a more important role in effective learning than policy demands and organizational CPD targets (Lee, 2011). Learning facilitated in the workplace involves practitioners in critical dialogue, cascading knowledge through situated learning to promote improved individual, team and organizational effectiveness and leadership (Manley et al., 2009). Systems and organizational leadership inspired with positive attitudes to change transform skill gaps into knowledge to improve adaptive capability and overall performance (Wiig et al., 2014).

5. Limitations

We acknowledge the limitations of this paper. The study omitted participants' professional backgrounds on assumption that all healthcare professionals are required to undertake some form of CPD for professional regulation and maintaining fitness to practice. It is thus possible that the study sample involved unequal representation of professions involved in frontline practice across the health economy.

The paper presents theoretical strategies for achieving optimal benefit from CPD activity in healthcare but does not provide indicators for expected outcomes. The impact of practitioner directed CPD on improvements warrants further investigation to develop indicators for tracking intended and non-intended outcomes.

6. Conclusion

Our study highlights the complex processes underlying healthcare practitioners' CPD activity. The resulting transformation theories contextualize CPD drivers and identify conditions conducive for CPD effectiveness. Practitioner driven CPD in healthcare is effective within supportive organizations, facilitated workplace learning and effective workplace cultures. Organizations and teams with shared values and purpose enable active generation of knowledge from practice and the use of different types of knowledge in practice for service improvements.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

Findings from this study have implications for all stakeholders with responsibility to make sure that practitioners are competent to meet varied population health needs and that care delivery is person centered, safe and effective. The evidence presented offers guidance to CPD stakeholders to be explicit and intentional in investing in CPD activity to achieve intended improvements.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study obtained ethical clearance from the University's Research Ethics and Governance Committee ref. 13/H&SC/CL67. All participants volunteered to take part in the study and each participant gave informed written consent. Information given in the online survey indicated that participants' decisions to continue with completing the survey was formal consent for their participation. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time if they wished to do so without giving explanations.

Funding Information

National Health Service Employers (ALB\061561.4010595) under the umbrella of the UK Department of Health funded the study. The funding body had no involvement in any of the research processes.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to Professor Jan Dewing, Sue Pembrey Chair of Nursing, Queen Margaret University for early contributions to the study methodology, literature review and analysis of data from the stakeholder survey.

Contributor Information

Kim Manley, Email: kim.manley1@canterbury.ac.uk.

Anne Martin, Email: anne.martin@canterbury.ac.uk.

Carolyn Jackson, Email: carolyn.jackson@canterbury.ac.uk.

Toni Wright, Email: toni.wright@canterbury.ac.uk.

References

- Bhatnagar K., Srivastava K. Job satisfaction in health-care organizations. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2012;21(1):75. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.110959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billett S. Critiquing workplace learning discourses: participation and continuity at work. Stud. Educ. Adults. 2002;34(1):56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter J. Evaluating social work education: a review of outcomes, measures, research designs and practicalities. Soc. Work. Educ. 2011;30(02):122–140. [Google Scholar]

- Draper J., Clark L. Impact of continuing professional education on practice: the rhetoric and the reality. Nurse Educ. Today. 2007;27(6):515–517. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper J., Clark L., Rogers J. Managers' role in maximising investment in continuing professional education: Jan Draper and colleagues look at ways to create positive cultures that make the most of learning in practice. Nurs. Manag. 2016;22(9):30–36. doi: 10.7748/nm.22.9.30.s29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S., Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Executive Agency for Health Consumers Study concerning the review and mapping of continuous professional development and lifelong learning for health professionals in the European Union. European Union. 2013. http://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/workforce/docs/cpd_mapping_report_en.pdf

- Filipe H.P., Silva E.D., Stulting A.A., Golnik K.C. Continuing professional development: best practices. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2014;21(2):134. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.129760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher L. Continuing education in nursing: a concept analysis. Nurse Educ. Today. 2007;27(5):466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs V. An investigation into the challenges facing the future provision of continuing professional development for allied health professionals in a changing healthcare environment. Radiography. 2011;17(2):152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Humphrey C., Hughes J., Macfarlane F., Butler C., Pawson R.A.Y. How do you modernize a health service? A realist evaluation of whole-scale transformation in London. Milbank Q. 2009;87(2):391–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00562.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim J.E. Continuing professional development: a burden lacking educational outcomes or a marker of professionalism? Med. Educ. 2015;49(3):240–242. doi: 10.1111/medu.12654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illeris K., editor. Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists… in Their Ownsss Words. Routledge; London: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kinley J., Stone L., Dewey M., Levy J., Stewart R., McCrone P., Sykes N., Hansford P., Begum A., Hockley J. Thsse effect of using high facilitation when implementing the gold standards framework in care homes programme: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Palliat. Med. 2014;28(9):1099–1109. doi: 10.1177/0269216314539785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N.J. An evaluation of CPD learning and impact upon positive practice change. Nurse Educ. Today. 2011;31(4):390–395. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Légaré F., Freitas A., Turcotte S., Borduas F., Jacques A., Luconi F. Responsiveness of a simple tool for assessing change in behavioral intention after continuing professional development activities. PLoS One. 2017;12(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane F., Greenhalgh T., Humphrey C., Hughes J., Butler C., Pawson R. A new workforce in the making? A case study of strategic human resource management in a whole-system change effort in healthcare. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2011;25(1):55–72. doi: 10.1108/14777261111116824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden C.A., Mitchell V.A. Bristol Policy Press; Bristol: 1993. Professions, Standards and Competence: A Survey of Continuing Education for the Professions. [Google Scholar]

- Manley K., Titchen A., Hardy S. Work-based learning in the context of contemporary health care education and practice: a concept analysis. Pract. Dev. Health Care. 2009;8(2):87–127. [Google Scholar]

- Manley K., Sanders K., Cardiff S., Webster J. Effective workplace culture: the attributes, enabling factors and consequences of a new concept. Int. Pract. Dev. J. 2011;1(2) [Google Scholar]

- Manley K., Martin A., Jackson C., Wright T. Using systems thinking to identify workforce enablers for a whole systems approach to urgent and emergency care delivery: a multiple case study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016;16(1):368. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1616-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A., Manley K. Developing standards for an integrated approach to workplace facilitation for interprofessional teams in health and social care contexts: a Delphi study. J. Interprof. Care. 2018;32(1):41–51. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2017.1373080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalski G.V., Cousins J.B. Differences in stakeholder perceptions about training evaluation: a concept mapping/pattern matching investigation. Eval. Program Plann. 2000;23(2):211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Moore G.F., Audrey S., Barker M., Bond L., Bonell C., Hardeman W. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty J., Manthorpe J. Post-qualifying education for social workers: a continuing problem or a new opportunity? Soc. Work. Educ. 2014;33(3):397–411. [Google Scholar]

- Moss J.D., Brimstin J.A., Champney R., DeCostanza A.H., Fletcher J.D., Goodwin G. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting (Vol. 60, No. 1, pp. 2005–2008) SAGE Publications; Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: 2016. Training effectiveness and return on investment: perspectives from military, training, and industry communities. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey R. How to be a good professional: existentialist continuing professional development (CPD) Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2013;41(3):267–276. doi: 10.1080/03069885.2013.773961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson R., Tilley N. SAGE Publications; London: 1997. Realistic Evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson R., Tilley N. Realist Evaluation. 2004. http://www.communitymatters.com.au/RE_chapter.pdf

- Pawson R., Greenhalgh T., Harvey G., Walshe K. University of Manchester; 2004. Realist Synthesis: An Introduction. ESRC Research Methods.http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.432.7999&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J.L., Piza M., Ingham J. Continuing professional development programmes for rural nurses involved in palliative care delivery: an integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today. 2012;32(4):385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price S., Reichert C. The importance of continuing professional development to career satisfaction and patient care: meeting the needs of novice to mid-to late-career nurses throughout their career span. Adm. Sci. 2017;7(2):17. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B.L. 2nd ed. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2000. Philosophical Foundations of Concept Development. Concept Development in Nursing; pp. 7–37. [Google Scholar]

- Roessger K.M. But does it work? Reflective activities, learning outcomes and instrumental learning in continuing professional development. J. Educ. Work. 2015;28(1):83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rycroft-Malone J. The PARIHS framework—a framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2004;19(4):297–304. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schostak J., Davis M., Hanson J., Schostak J., Brown T., Driscoll P. ‘Effectiveness of continuing professional development’ project: a summary of findings. Med. Teach. 2010;32(7):586–592. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.489129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace S., May S.A. Assessing and enhancing quality through outcomes-based continuing professional development (CPD): a review of current practice. Vet. Rec. 2016;179(20):515. doi: 10.1136/vr.103862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watling T. Factors enabling and inhibiting facilitator development: lessons learned from essentials of Care in South Eastern Sydney Local Health District. Int. Pract. Dev. J.s. 2015;5(2) [Google Scholar]

- Whetten D.A. What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989;14(4):490–495. [Google Scholar]

- Wiig S., Robert G., Anderson J.E., Pietikainen E., Reiman T., Macchi L., Aase K. Applying different quality and safety models in healthcare improvement work: boundary objects and system thinking. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2014;125:134–144. [Google Scholar]

- Yin R.K. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2003. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. [Google Scholar]