Summary box.

Since 2013, Kenya's public health sector has been affected by frequent short strikes, culminating in nationwide strikes lasting a total of 250 days by doctors and nurses in a span of 11 months in 2016/17.

Health professionals have the right to go on strike, but their strikes crippled health services with almost no public hospital inpatient services being provided, thus violating people’s right to healthcare.

To avoid similar instances in the future, mechanisms should be established for dispute resolution, anticipating and pre-empting changes within the health system that result to conflict between parties.

There are no ‘magic bullets’ to avert all problems due to these strikes in what are complex, politically managed and highly professionalised health-sector organisations.

Reactive solutions such as sacking striking workers, jailing trade union officials neither address the underlying problems nor build resilience of the health system.

Introduction

Since devolution of healthcare services in 2013, the Kenyan public health sector has been affected by frequent short and often localised strikes.1 These were followed by a public-sector nationwide doctors’ strike lasting 100 days (from 5 December 2016 to 14 March 2017) and then the nurses’ strike lasting 150 days (from 5 June to 1 November 2017), a total of 250 strike days in a span of 11 months, referred to hereafter as the 2017 strikes. The strikes resulted from a complex chain of events briefly outlined below.

A new 2010 Kenya Constitution gave every worker (with some exceptions for disciplined armed forces) the rights to join a union, engage in collective bargaining and the freedom to strike, linked to supporting rights to fair remuneration and reasonable working conditions.2 This constitution also devolved all primary and secondary health services to 47 new semiautonomous county governments. Initial plans were to progressively transfer functions over a 3-year transition period from 2013.2

However, political pressures resulted in devolution of health services occurring over 6 months to counties that had limited capacity in human resource for health (HRH) and medical supplies management. Salary delays and challenges managing career progression agreements and postgraduate training schemes, long stock-outs of essential medicines and discrimination against persons perceived to be outsiders were reported from some counties in the 3 years preceding the 2017 strikes.1 During this period, doctors and nurses formed trade unions.3 4 The doctors negotiated collective bargaining agreements (CBA) on pay and working conditions, which was reportedly signed by the national government in 2013 but not implemented and county governments did not then accept responsibility for it.5 Both the national and county government are reported to have failed to sign the draft nurses’ CBA that encouraged them to return to work after a 2-week strike in December 2016 resulting in the prolonged 2017 nurses’ strike. Table 1 summarises the events that led to the 2017 strikes.

Table 1.

Occurrence of events that led to the doctors’ and nurses’ strikes in Kenyan public hospitals

| Year | Events | What the event entailed | Implications |

| 2010 | The promulgation of the 2010 constitution2 |

|

|

| 2011–2012 | Doctors’ Union formed3 |

|

|

| 2013 | A CBA drafted by Doctors’ Union and Ministry of Health and reportedly signed by both parties |

|

|

| 2013 | New government formed following general elections |

|

|

| 2013 | Registrar of Trade Unions directed by the court to register nurses’ union4 |

|

|

| 5 December 2016 to 15 March 2017 | Doctors’ nation-wide strike in demand of fulfilment of the 2013 CBA |

|

|

| 5−14 December 2016 | Nation-wide nurses’ strike |

|

|

| 5 June to 2 November 2017 | Nation-wide nurses’ strike |

|

|

CBAx, Collective bargaining agreement.

The consequences of the strikes on hospital admissions

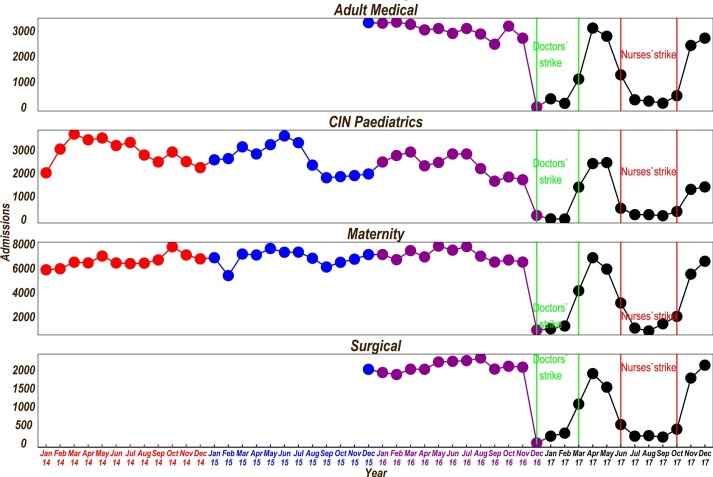

Data from 13 county public hospitals that provide first-referral care illustrate the effects of the 2017 strikes. These hospitals are part of the Clinical Information Network (CIN) since 2013/2014 whose aim is to improve quality and utilisation of hospital data. While they are not a nationally representative sample of hospitals, we believe their data reasonably mirror the pattern of hospital admissions in other county hospitals (they are described in more detail elsewhere).6 Data on paediatric admissions were taken from the ongoing CIN surveillance platform and for other wards were obtained from the hospitals’ health-records departments.

We present a 2-year data pooled from all hospitals on the number of admissions per month in the four major inpatient wards from January 2016 to December 2017. We use the data from January 2014 to December 2015 for the paediatrics and maternity wards to demonstrate annual patterns of admissions and any seasonality that might exist.

During both the doctors’ and nurses’ 2017 strikes, there were marked reductions in admissions in all the four major disciplines—obstetrics, paediatrics, surgical and adult medicine (figure 1). Exploration of hospital-specific data (available on request) demonstrates varied responses to the strikes across hospitals and wards. There was limited continuing admissions in different hospitals in specific wards (maternity (n=1/13), adult medical (n=1/13) and surgical (n=1/13)); resumption of services before the strikes officially ended (in two maternity wards and across all wards in two hospitals) and use of locum nurses to keep all the wards open (one hospital). During the entire 250 days of the strike, four hospitals had almost no admissions at all.

Figure 1.

Admissions over time across wards in 13 CIN hospitals. CIN, Clinical Information Network.

Considering the admissions in the prestrike year (December 2015 to November 2016), we speculate that a total of 183 170 individuals (including that each maternity admission produced one new-born) did not receive admission care in these 13 hospitals during strike year (December 2016 to November 2017). This included 59 965 maternity patients (and the same number of newborns), 24 762 medical patients, 20 309 paediatrics and 18 169 surgical patients. There are 65 similar level referral hospitals in Kenya (Kenya Master Facility List), and we tracked data from 13 of these that were part of CIN, suggesting that preventable deaths likely occurred on a massive scale. Private and faith-based hospitals reported increased admissions and mortality over this period.7 Typically, county hospitals see many more outpatients than inpatients and so the total number of lost episodes of care in the public sector would be considerably higher.

No ‘Magic bullets’

There are no ‘magic bullets’ to avert all problems due to these strikes in what are complex, politically managed and highly professionalised health-sector organisations. Where there is a right to health professionals’ industrial strike, appropriate mechanisms are required to avert harms. Reactive solutions such as sacking striking workers and jailing trade union officials neither address the underlying problems nor build resilience of the health system.1 5 8 Instead, there is a clear imperative to improve the management of HRH and develop proactive policies and risk management plans that nurture systems’ ability to withstand crises while maintaining functions.9 Data from the 13 hospitals in the CIN indicate that two of the hospitals had 1-day strikes in 2014, seven had strikes ranging from 1 to 49 days in 2015, and in 2016 (January to November), all hospitals had strikes for periods ranging from 27 to 59 days. Such data suggest there were clear warning signs of deteriorating relationships that did not prompt mitigating actions.

HRH strikes raise a moral dilemma with the potential of causing harm to patients, violating professional ethics and the Hippocratic oath. Yet, HRH strikes may be justifiable if there is evidence of long-term benefits to the doctors, patients and overall quality of care.10 Importantly, in Kenya, although the public sector is said to provide 48% of all Kenya’s healthcare, it provides a much greater proportion of inpatient hospital care particularly for the 36.1% (18 million) of Kenya’s population living in poverty (Kenya Economic Survey 2018). Strikes thus disproportionately affect the poor who are unable to afford private sector alternatives. This population therefore deserves special ethical consideration when health professionals’ strikes are contemplated.

Rebuilding relationship among stakeholders

National and county healthcare leadership need to rebuild relationships with professional groups who, in turn, need to better define their own professional norms and values11 so that, during health system level ‘shocks’ professional and societal values might be better aligned. Spaces need to be created for all groups to contribute to planning of healthcare and policies that are cognizant of economic and social realities spanning training, deployment of staff, management of performance and definition of working conditions.12 Such efforts are needed to rebuild trust.

Specifically, there needs to be a national and inclusive dialogue (with patient representation) to develop minimum operating requirements in the event of strikes to prevent the near total collapse of the public health system seen in 2017.9 This is especially important as the Kenya Constitution permits HRH strikes and also states that ‘A person shall not be denied emergency medical treatment’.2 Special consideration therefore needs to be given to handling of emergencies, ensuring continued care of already hospitalised patients and how to safely staff vital facilities, such as the emergency rooms, obstetric and neonatal departments.13 In some countries, for example, senior clinicians continue to give services when junior staff are on strike.14 This arrangement provides at least some cover while maintaining positive elements of an overarching professional ethos. These risk management plans are best agreed on outside times of crisis and might be enshrined in specific agreements or even in the Constitution or Government legislation. Such actions need to be taken now.

Going further, a specific forum could be created, including senior representatives of all parties, to regularly meet to discuss health system challenges before they escalate to strike action. Such a forum may have facilitated discussions on the issues raised by the Doctors’ Union that were articulated in the 2012 Musyimi Task Force Report.15 It could also help in planning how best to deliver healthcare in times of natural or other hazards (epidemics, natural disasters) and should have the opportunity to discuss implementation of major proposed health-system reforms such as devolution/decentralisation of health services. The forum should include representatives from national and county governments, health professional associations and their unions, medical teaching institutions, private/faith-based healthcare providers, communities and partners in healthcare with an aim to build collaboration among stakeholders. As a further precaution, mechanisms for effective, fair and independent arbitration should be developed and agreed to by all parties in advance of any future strike action. Most important is that employers and employees should honour agreements made and act in good faith for the benefit of the whole population and especially its most vulnerable groups.

Conclusion

The health professionals’ strikes crippled the health services with almost no public hospital inpatient services being provided and violating people’s right to healthcare. To avoid similar instances in the future, the specific roles and responsibilities of the national and county governments should be clearly defined in a devolved health system. Mechanisms should be established for dispute resolution, anticipating and pre-empting changes within the health system that result to conflict between parties. Complexity of health systems should be taken into consideration in problem and solution identification.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Kenya Ministry of Health who gave permission for this work to be developed and have supported the implementation of the Clinical Information Network (CIN) together with the county health executives and all hospital management teams in the network. They are grateful to the Kenya Paediatric Association, the Ministry of Health and the University of Nairobi for promoting the aims of the CIN and the support they provide through their officers and membership. They also thank the hospital clinical teams on all the paediatric wards who provide care to the children for whom this project is designed. This work would not have possible without the leadership of the paediatricians, nurses and the Health Information Record Officers in this network who contributed to the development of CIN and data collection. This work is published with the permission of the Director of KEMRI.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript. GM compiled data from the hospitals, MO conducted the analyses with support from GI and ME. GI took the primary responsibility for manuscript development and feedback on the logic approach was provided by ME, DG, CK, SA, EB and BT. All authors then approved the final draft.

Funding: This work was supported by funds from the Wellcome Trust (#097170) awarded to ME as a Senior Fellowship together with additional funds from a Wellcome Trust core grant awarded to the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme (#092654).

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the KEMRI Scientific and Ethical Review Unit for the research on which this report is based.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data for this report are under the primary jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health in Kenya. Enquiries about using the data can be made to the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme Data Governance Committee.

References

- 1. Tsofa B, Goodman C, Gilson L, et al. . Devolution and its effects on health workforce and commodities management - early implementation experiences in Kilifi County, Kenya. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:169 10.1186/s12939-017-0663-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Constitution K. Government printer. Kenya Nairobi, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mwenda AS. From a dream to a resounding reality: the inception of a doctors union in Kenya. Pan Afr Med J 2012;11:16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kenya Law , 2013. Kenya Law Reports: Petition 50 of 2012. Available from: http://kenyalaw.org/caselaw/cases/view/88334

- 5. Nation D. Judge Wasilwa orders KMPDU chiefs to serve a month in jail, 2017. Available from: https://www.nation.co.ke/news/Judge-jails-kmpdu-officials-for-contempt/1056-3810872-nlkcupz/index.html

- 6. Ayieko P, Ogero M, Makone B, et al. . Characteristics of admissions and variations in the use of basic investigations, treatments and outcomes in Kenyan hospitals within a new clinical information network. Arch Dis Child 2016;101:223–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adam MB, Muma S, Modi JA, et al. . Paediatric and obstetric outcomes at a faith-based hospital during the 100-day public sector physician strike in Kenya. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000665 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nation D, 2017. Kenyan nurses end their 5-month strike after deal with State. Available from: https://www.nation.co.ke/news/Kenyan-nurses-end-4-month-strike-after-deal-with-State/1056-4166940-mo35skz/index.html

- 9. Barasa E, Mbau R, Gilson L. What is resilience and how can it be nurtured? A systematic review of empirical literature on organizational resilience. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abbasi IN. Protest of doctors: a basic human right or an ethical dilemma. BMC Med Ethics 2014;15:24 10.1186/1472-6939-15-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferlie E, Fitzgerald L, Wood M, et al. . The nonspread of innovations: the mediating role of professionals. Acad Manage J 2005;48:117–34. 10.5465/amj.2005.15993150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dussault G, Dubois CA. Human resources for health policies: a critical component in health policies. Hum Resour Health 2003;1:1 10.1186/1478-4491-1-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gafni-Lachter L, Admi H, Eilon Y, et al. . Improving work conditions through strike: examination of nurses' attitudes through perceptions of two physician strikes in Israel. Work 2017;57:205–10. 10.3233/WOR-172560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Robinson G, McCann K, Freeman P, et al. . The New Zealand national junior doctors' strike: implications for the provision of acute hospital medical services. Clin Med 2008;8:272–5. 10.7861/clinmedicine.8-3-272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Strengthening Health Service Delivery Report of the taskforce constituted to address health sector issues raised by the Kenya medical practitioners, pharmacists and dentists union, 2012. Available from: http://publications.universalhealth2030.org/uploads/musiyimi_report.pdf