Abstract

Adenosine to inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing occurs in a wide range of tissues and cell types and can be catalyzed by one of the two adenosine deaminase acting on double-stranded RNA enzymes, ADAR and ADARB1. Editing can impact both coding and noncoding regions of RNA, and in higher organisms has been proposed to function in adaptive evolution. Neither the prevalence of A-to-I editing nor the role of either ADAR or ADARB1 has been examined in the context of germ cell development in mammals. Computational analysis of whole testis and cell-type specific RNA-sequencing data followed by molecular confirmation demonstrated that A-to-I RNA editing occurs in both the germ line and in somatic Sertoli cells in two targets, Cog3 and Rpa1. Expression analysis demonstrated both Adar and Adarb1 were expressed in both Sertoli cells and in a cell-type dependent manner during germ cell development. Conditional ablation of Adar did not impact testicular RNA editing in either germ cells or Sertoli cells. Additionally, Adar ablation in either cell type did not have gross impacts on germ cell development or male fertility. In contrast, global Adarb1 knockout animals demonstrated a complete loss of A-to-I RNA editing in spite of normal germ cell development. Taken together, these observations demonstrate ADARB1 mediates A-to-I RNA editing in the testis and these editing events are dispensable for male fertility in an inbred mouse strain in the lab.

Keywords: spermatogenesis, RNA editing, Sertoli cells, spermatocytes, meiosis, spermatids, adenosine deaminase, ADAR, RNA modification

Summary Sentence

Testicular A to I editing occurs primarily in meiotic and postmeiotic germ cells and is catalyzed by the editing enzyme ADARB1.

Introduction

RNA biology is extraordinarily complex, with multiple layers of regulation combined in cell-dependent manners to modulate the primary, secondary, and tertiary structure of all types of RNA; from transfer RNAs to messenger RNA (mRNA). In addition to the traditionally recognized RNA biogenesis steps of transcription, splicing and transport, increasing attention has been paid to the importance of covalent RNA modifications in normal physiology.

RNA editing, a type of irreversible RNA modification, occurs in two classically defined types in mammals: adenosine to inosine (A-to-I) and cytosine to uracil (C-to-U). Based on computational analyses, A-to-I RNA editing appears to be more widespread than C-to-U in mammals, impacting a much wider range of targets and being observed in a wider range of tissues [1]. The effects of editing on a given target vary widely. The canonical example of A-to-I editing is the neural glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA2 (Gria2) in which multiple sites in the mRNA are edited to varying degrees thus altering the encoded amino acids and changing the physiological function of the receptor [2]. Editing of other mRNAs has been shown to impact events besides coding potential including splicing, transcript stability, and microRNA (miRNA) regulation [3]. Functionally, RNA editing has been implicated in generating proteome diversity [4], regulating innate immunity [5], and driving adaptive evolution [6].

A-to-I editing is catalyzed by a family of RNA-specific adenosine deaminase enzymes (ADARs), of which there are three in the mouse (ADAR, ADARB1, and ADARB2 corresponding to human ADAR1, ADAR2, and ADAR3) [4]. ADARs are conserved across a wide range of eukaryotic phyla [7,8] and are composed of two protein domains: an adenosine deaminase (AD) domain that catalyzes the deamination of A-to-I and one or more double stranded RNA-binding domains. ADAR and ADARB1 are known to catalyze A-to-I RNA editing while the third ADAR, ADARB2, is believed to be catalytically inactive [9]. While expression of Adarb2 is confined almost exclusively to neural tissue, Adar and Adarb1 are observed in a wider range of tissues suggesting RNA editing may occur in multiple tissues [10,11].

For many years, the list of known edited targets was extremely limited, with identification occurring either serendipitously or via low-throughput screens of EST libraries. The majority of studies also focused on a limited range of tissue types. As a result of this, the breadth of A-to-I RNA editing both within and across tissues was unclear. With the increasing availability of high-throughput RNA sequencing, a large number of potential RNA-editing targets have been identified [1,12–14] within numerous tissues suggesting RNA editing is even more widespread than previously believed.

A number of genetic models targeting ADAR or ADARB1 have been developed. Global loss of Adar results in embryonic lethality [15] making analysis of tissue-specific functions impossible in the adult. In contrast, global deletion of Adarb1, although resulting in neonatal lethality, can be overcome by genomic mutation of a single known ADARB1 editing site [16]. While suggesting a highly specific role for ADARB1 in normal mouse neurophysiology, these studies do not inform on whether ADARB1 plays a function in other tissues. Conditional ablation of Adar in various cell types of the hematopoietic system has demonstrated functionally important roles for Adar in at least one adult system; however, no similar analyses have been undertaken in other tissues.

The adult testis contains multiple somatic and germ cell types that function together to produce mature sperm. The primary somatic cell type in the testis, the Sertoli cell, physically surrounds the germ cells and provides the necessary microenvironment for their differentiation. The various germ cell populations represent successive phases of differentiation: mitotic spermatogonia, meiotic spermatocytes, postmeiotic spermatids, and mature spermatozoa. In each case, distinct RNA processing pathways are at play and required for normal progression although the role of RNA editing in normal germ cell development has not previously been examined. Here we genetically investigated the role of Adar and Adarb1 during murine spermatogenesis.

Materials and methods

Animal model generation and husbandry

Animals carrying the Adartm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi (Adartm1a) allele were obtained from the European Mouse Mutant Archive and used to establish an Adartm1a breeding colony. This allele is a knockout-first, conditional-ready allele that can be used to generate a floxed, conditional allele after flippase (FLP)-recombinase-mediated recombination. A delete allele can then be generated via Cre-recombination. Additional details about the Adartm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi allele and its derivatives can be found at http://www.mousephenotype.org/data/genes/MGI:1889575. The Adartm1c (hereafter referred to as AdarFl) allele was obtained by crossing Adartm1a carriers to B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(FLP1)Dym/RainJ followed by backcrossing to C57BL/6J to remove the Flp allele. The AdarDel allele was generated by crossing AdarFl allele carriers to mice carrying the Tg(Stra8-iCre)1Reb allele that had been backcrossed into the C57BL/6J background. Experimental AdarDel/Fl animals were then generated by crossing into the necessary Cre-carrying mice (Tg(Stra8-iCre)1Reb and Tg(Amh-cre)8815Reb). All experimental mice used in this study were cared for in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals” established by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and all protocols approved by the Jackson Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were maintained in a 12 h light and 12 h dark cycle vivarium in the Research Animal Facility at The Jackson Laboratory. Autoclaved NIH31 diet (6% fat) and HCl acidified water (pH 2.8–3.2) were provided ad libitum.

RNA sequencing

Paired-end RNA sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 at The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Total RNA extraction via the mirVana RNA isolation kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) was performed per manufacturers, including DNase treatment. RNA-sequencing libraries for 100 bp paired-end sequencing were produced using the TruSeq RNA Sample prep Kit v2 Set A and B (Illumina, San Diego, CA), accession number: GSE92870. Single-end 76 bp RNA-seq strand-specific reads derived from isolated testicular cell types were obtained from the SRA database (GEO accession numbers GSE43717, GSE43719, and GSE43721 [17]).

Computational identification of RNA editing

RNA-editing site identification was performed using RNA-sequencing data from whole late juvenile (25 dpp) testes and publically available RNA-sequencing data derived from isolated testicular cell types. The computational pipeline was based on one previously reported [18]. Briefly, the first 6 bp of each read were trimmed and each read aligned to the mm10 genome via TopHat (https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml) using an inner mate distance of 100 bp with default parameters. Following alignment, variants were defined using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) UnifiedGenotyper (https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/) with the following parameters: filter_reads_with_N_cigar -stand_call_conf 0 -stand_emit_conf 0 -mbq 25 -rf MappingQuality -mmq 20. Further filtering was used to select only sites with a single nucleotide variant, read depth of greater than 10, observed in all replicates of a given type, overlapping with known exons, and a frequency of 5% to 95%. From these sites, any sites residing in exons with multiple variant types and sites residing at locations of known single nucleotide polymorphisms for any of the common mouse strains were removed.

Inosine chemical erasing analysis

Confirmation of inosine incorporation was based on a previously published protocol [19]. In brief, total RNA from whole adult C57BL/6J testes was extracted via Trizol Reagent using manufacturer's recommended methods. Ten microgram of isolated RNA was DNase I (Qiagen) treated, purified by RNeasy MiniElute clean up (Qiagen), and cyanoethylated in a 50% v/v ethanol:1.1M triethylammoniumacetate (pH = 8.6) with or without 1.6 (1×), 6.2 (2×), or 12.4 (4×) M acryolonitrile at 70°C for 30 min. RNA was then purified by RNeasy MiniElute clean up and used as template for cDNA synthesis by Superscript III RT (Life Technologies) and random hexamer priming. cDNA was then subjected to editing site-specific (Rpa1—F: CTCAGAGGGCTGTGTGTGAA and R: AGACAAAAAGGTGCCACCAC. Cog3—F: CACAGACGACGATCTCTCCA and R: TGAACTCCTCCAGCTGCTCT) or control (Rps2—F: CTGACTCCCGACCTCTGGAAA and R: GAGCCTGGGTCCTCTGAACA) target amplification followed by PCR purification (QIAquick PCR purification, Qiagen) and Sanger sequencing using the forward primer for each product. C57BL/6J genomic DNA was isolated via DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen), amplified using site-specific primers (Rpa1—see above, Cog3—F: GACTCGTTCTCGGAGCTTTG and R: CTGTGCTGACACACCTGGAC), and sequenced using the respective forward primer.

Quantitative RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing analysis

Total RNA from Adar:Cre mutants, Cre- litter mates, and C57BL/ 6J whole adult testes or whole embryos was extracted by Trizol Reagent using manufacturer's recommended methods. Isolated RNA was DNase I (Qiagen) treated and cDNA synthesized using Superscript III RT (Life Technologies) and random hexamer priming. SYBR Green quantitative RT-PCR utilized the following primers for detection of Adar or Adarb1. Relative fold changes were calculated as previously reported [20] using Rps2 as the endogenous control. Sanger sequencing analysis of Rpa1 and Cog3 editing utilized the same primers as for inosine chemical erasing (ICE) analysis.

Fertility analysis and sperm counts

Adult Adar:Cre mutants and Cre- litter mate control male mice were mated with fertile C57BL/6J females (6–8 weeks old) and litter number and size recorded for a period of 4 months. To quantify sperm, epididymides were dissected from adult mice and diced in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The diced tissue was incubated at 37°C for an hour, diluted 1:10 in PBS, and counted using a hemocytometer. Duplicate counts were evaluated for each mouse sample.

Histological evaluation

Testes and epididymides were dissected from adult mice and fixed overnight in Bouin's fixative before embedding in paraffin wax. Sections (5 μm) were stained with periodic acid–Schiff's reagent. Histological samples were imaged using a Zeiss Axioscop microscope with filterset 10. Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe Systems) was used for cropping and background color correction.

Results

Testicular RNA editing occurs in a cell-type dependent manner

RNA-sequencing data from late juvenile (25 dpp) whole testis and isolated testicular cell types were used to identify putative A-to-I RNA-editing targets in the testis. This dataset included six biological replicates each of whole late juvenile testis along with three each of isolated Sertoli cells, spermatogonia, spermatocytes, spermatids, and spermatozoa [21]. RNA-editing events were defined for each independent sample using a modified GATK variant caller (see Materials and Methods) based on previously published RNA-editing identification pipelines [18]. Analysis of a stringent list of sites detected in all three replicates of at least one cell type (Figure 1A) demonstrated that A-to-I editing occurs at only a few sites (21) throughout the testis transcriptome, a finding consistent with previous reports demonstrating RNA editing in the testis is rare relative to other tissues [22]. For example, a similar analysis of adipose, liver, and bone identified 47, 60, and 104 A-to-I RNA-editing events, respectively [1]. Although rare, the number of testicular RNA-editing events varied by cell type with the majority of sites occurring in the Sertoli cell.

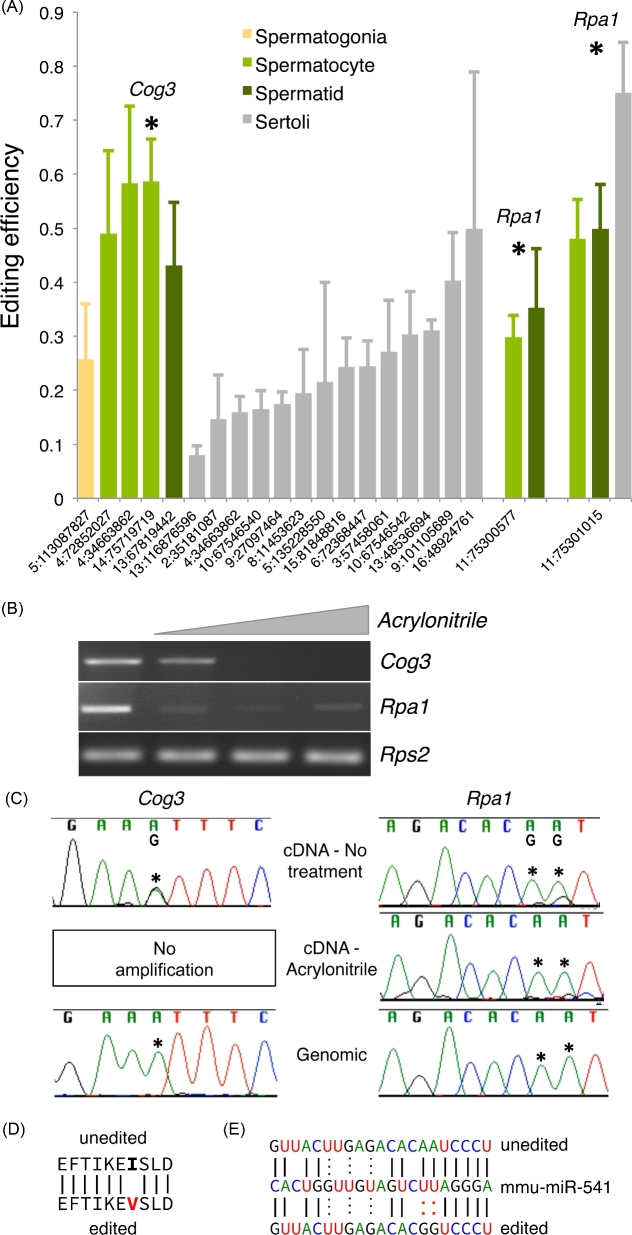

Figure 1.

RNA editing is rare and cell-type dependent in the testis. (A) Editing efficiency of computationally identified A-to-I RNA-editing sites in RNA-sequencing data of isolated testicular cell populations (n = 3). X-axis coordinates—editing site location within the genome. Asterisks—sites also identified in whole testis RNA-sequencing data (n = 6), host genes selected for further study indicated above respective editing sites. Error—standard deviation. (B) Molecular confirmation of inosine incorporation by acrylonitrile treatment. (C) Sanger sequencing of untreated cDNA, acrylonitrile treated cDNA, and genomic DNA to confirm editing, inosine incorporation, and genotype. Asterisks—editing sites. Impact of editing event on the (D) coding potential of Cog3 and (E) a microRNA recognition site in the 3΄ UTR of Rpa1.

Computational identification of RNA-editing events is unusually prone to false positives [23]. Supporting this notion, relatively few sites were found to be in common between the isolated cell RNA-sequencing datasets and the whole late juvenile testis RNA-sequencing datasets, and many reads informative to computationally defined sites included additional mismatches not attributable to RNA editing. To establish the rate of false positives in our analysis pipeline, Sanger sequencing confirmation of the 11 RNA-editing sites with editing frequencies above 25% was undertaken. A computationally defined site was considered confirmed if the computed site was observed as a mixed A/G peak using Sanger sequencing, and the amplicon did not contain any additional nonediting mixed peaks. This analysis did confirm a high rate of false positives with only the three sites being identified in all three cell-type specific datasets and in all six whole late juvenile testis datasets showing reliable mixed A/G peaks using Sanger sequencing (Figure 1B and C). Three sites in only two genes, Cog3 and Rpa1, passed the computational and molecular filtering criteria. These mRNAs were subjected to ICE, a method to directly detect inosine at specific sites of intact RNA by the formation of a reverse-transcriptase blocking nucleotide adduct with acrylonitrile treatment [19]. This method provides high-confidence confirmation of true A-to-I changes. Additional in silico translation and microRNA recognition site analyses demonstrated the potential functional relevance of the confirmed editing events, with editing of Cog3 predicted to alter its coding potential and editing in the 3΄ untranslated region (UTR) of Rpa1 altering the recognition sequence of a miRNA-binding site (Figure 1D and E).

RNA-editing efficiency, or the fraction of nucleotides at a given site that undergo editing, was calculated based on the frequency of editing nucleotides observed in aligned RNA-sequencing reads for each site. Editing efficiency of the confirmed editing sites varied between cell types with editing of Cog3 exclusive to meiotic spermatocytes, one site of Rpa1 editing observed in meiotic spermatocytes and postmeiotic spermatids, and the other site of Rpa1 editing observed in meiotic and postmeiotic germ cells as well as Sertoli cells. This may be a result of cell-specific regulation of RNA-editing or cell-specific availability of RNA targets. To differentiate between these two possibilities, expression of Cog3 and Rpa1 was compared across the five cell types (Supplemental Figure 1). For Rpa1, the majority of the expression is derived from meiotic spermatocytes and postmeiotic spermatids while Cog3 expression is highest in spermatogonia and spermatozoa. Comparison of mRNA abundance by cell type and cell-type dependent editing shows no direct correlation suggesting RNA editing itself is regulated in a cell-type dependent manner.

The testis expresses multiple editing enzymes in a cell-type dependent manner

Computational analysis and molecular confirmation of editing events in the testis demonstrated RNA editing to be rare and regulated in a cell-type dependent manner. To determine which of the two catalytically active RNA adenosine deaminases is driving RNA editing detected in the testis, Adar and Adarb1 expression was examined across various tissues and throughout testis development by quantitative RT-PCR and in isolated cell types by RNA sequencing. Although Adar expression in the testis is substantially lower than in editing-rich tissues such as the brain, the observed expression is similar to that of non-neural tissues known to undergo A-to-I editing such as liver and lung [1] (Figure 2A). Additional analysis shows both Adar and Adarb1 have variable expression throughout testis development (Figure 2B).

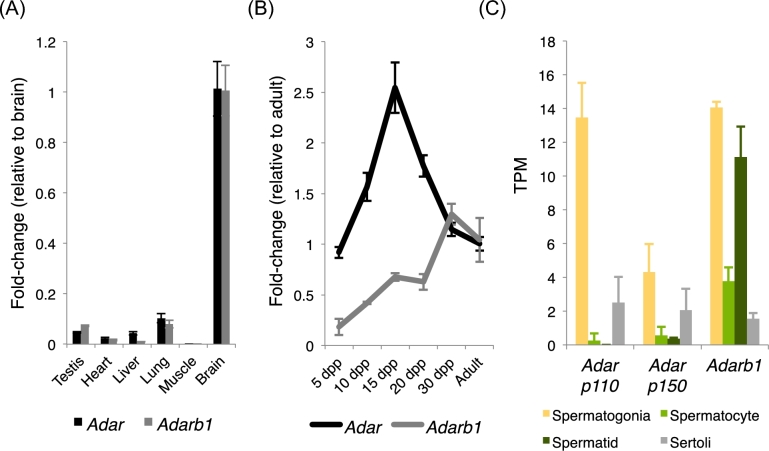

Figure 2.

A-to-I RNA-editing enzymes are expressed in the testis. Quantitative RT-PCR detection of RNA-editing enzyme expression (A) across multiple adult tissues and (B) throughout testicular development. N = 3, error—standard deviation, dpp—days postpartum. (C) RNA-sequencing quantification of RNA-editing enzyme isoform expression across isolated testicular cell types. N = 3, error—standard deviation. TPM—transcripts per million.

To more directly measure the potential cell-specific activity of the known RNA-editing enzymes, RNA-sequencing analysis was used to examine cell-type dependent expression of Adar and Adarb1 (Figure 2C). Alternative promoter usage generates two Adar mRNA isoforms: one producing a long (p150) protein that is cytoplasmic, normally associated with infection, and acts to edit viral RNAs, and a second isoform producing a short (p110) protein which is predominantly nuclear and functions as the ubiquitous editing enzyme for a wide range of substrates [24]. Cell-type specific expression profiling demonstrated both Adar isoforms were expressed predominantly in spermatogonia whereas Adarb1 was expressed in multiple germ cell types ranging from the mitotic spermatogonia to the postmeiotic spermatids. Given the observed expression profile, it was unclear which RNA-editing enzyme may drive RNA-editing events in the testis. In order to more accurately assess this question, a series of RNA-editing enzyme knockout models were generated and tested for their impacts on testicular RNA editing.

The Adartm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi allele and its derivatives properly target Adar

As global loss of Adar results in embryonic lethality, a conditional Adar ablation model (AdarFl) was developed in order to assess Adar function exclusively in Sertoli or differentiating germ cells. AdarFl was derived from the EUCOMM allele Adartm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi (Adartm1a) in which a reporter and selection cassette was inserted upstream of exon 3 (Figure 3A). This type of knockout first targeting scheme results in global gene ablation prior to cassette excision via FLP-mediated recombination. In order to confirm correct targeting of Adartm1a in vivo, Adar expression and the embryonic phenotype of homozygous carriers was assessed. Adar expression was reduced in a dose-dependent manner in Adartm1a heterozygote whole embryos and entirely lost in homozygous carriers, demonstrating the allele correctly inactivated the Adar locus (Figure 3B). Further supporting the utility of this model for examining ADAR function, we obtained no homozygous offspring from a heterozygous by heterozygous cross (Figure 3C), consistent with previous reports showing global Adar loss results in embryonic lethality between E12.5 and E14.5. From these data, it appears Adartm1a, and thus any derivative alleles, properly target Adar in vivo.

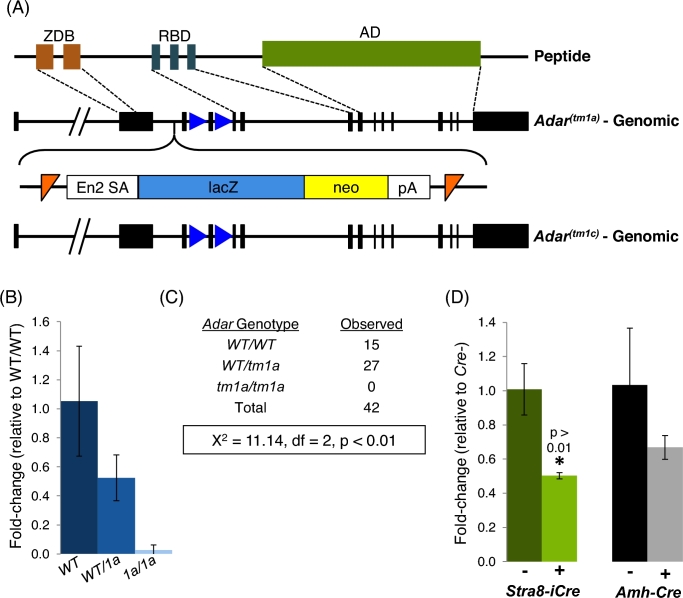

Figure 3.

AdarFl is a functional conditional allele of Adar. (A) Conditional targeting scheme for AdarFl utilizing a FRT-flanked (orange triangles) lacZ-neo reporter cassette followed by a loxP-flanked (blue triangles) exon 4 to generate a knockout first allele. Following FLP-recombinase, a conditional allele is generated that retains the floxed exon 4. ZDB—zDNA-binding domain, RBD—RNA-binding domain, AD—adenosine deaminase domain, En2 SA—splice acceptor, neo—neomycin selection cassette, pA—polyadenylation signal, FRT—Flp-recombinase recognition target site. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR of Adar in E11.5 wildtype (WT) and Adartm1a (1a) whole embryos. N ≥ 4, error—standard deviation. (C) Genotypes of juvenile offspring derived from WT/Adartm1a heterozygous crosses. Chi-squared analysis demonstrating significant reduction of Adartm1a homozygous offspring. df—degrees of freedom. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR of Adar in conditional ablation models (Stra8-iCre: differentiating germ cell and Amh-cre: Sertoli cell). N = 4, error—standard deviation.

Given confirmation of correct targeting, a conditional Adar allele (AdarFl) was generated by FLP-mediated cassette excision. Following cassette excision, a global Adar delete allele was generated by intercrossing AdarFl to Stra8-iCre expressing mice for two generations to produce offspring with a global Adar exon 4 deletion (AdarDel). To generate germ cell-specific conditional Adar knockouts, offspring of the above intercross carrying Stra8-iCre and AdarDel were backcrossed to AdarFl and males with the necessary experimental genotypes (AdarDel/Fl animals with or without Stra8-iCre) selected for study. For Sertoli cell conditional Adar ablation, AdarDel-carrying animals were crossed to Amh-Cre-expressing mice. Animals carrying both AdarDel and Amh-Cre were then crossed to AdarFl mice to generate the two experimental genotypes (AdarDel/Fl animals with or without Amh-Cre). All analyses were completed on a heterozygous Adar deletion background to ensure high Cre-excision efficiency [25]. In the case of Stra8-iCre, ablation was also confirmed by the observation that offspring of male AdarDel/1c individuals always carried the AdarDel allele. In both ablation models, AdarDel/Fl in the presence of Cre resulted in a reduction but not total loss of Adar expression in whole adult testis (Figure 3D), further confirming targeting and the conditional nature of the allele.

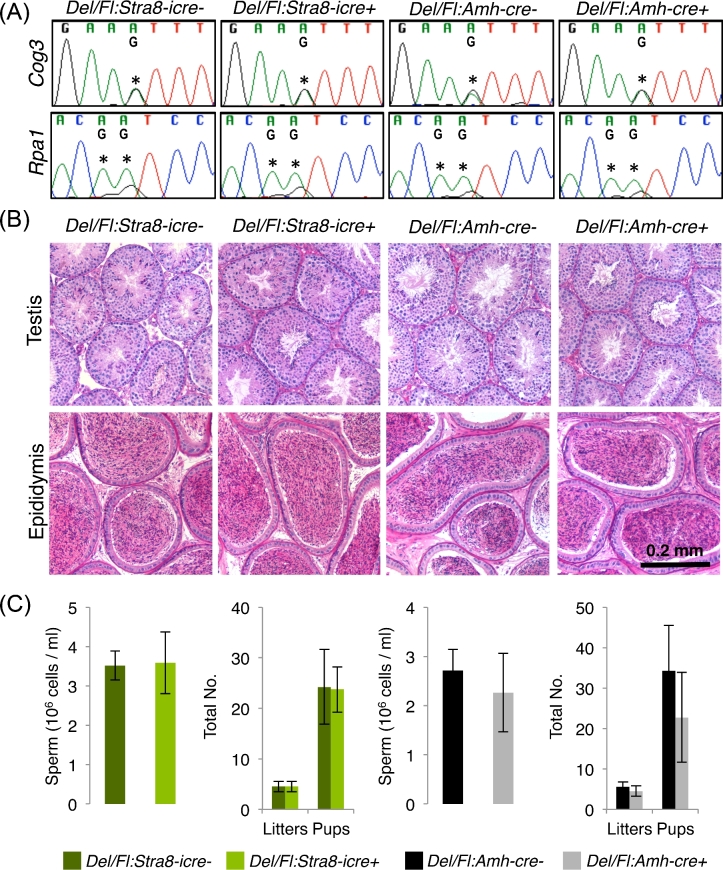

ADAR loss has no impact on testicular RNA editing or germ cell development

Given the expression of Adar and the observation of RNA-editing events in the testis, the impact of germ cell or Sertoli cell Adar loss on testicular RNA editing was examined by Sanger sequencing. At all sites examined, neither Sertoli nor germ cell ADAR loss resulted in any change in RNA editing (Figure 4A). To assess if Adar played some other important role in differentiating germ cells or the Sertoli cell, adult testis and epididymal morphology was assessed in the conditional ablations models. In both cases, the testis contained a normal complement of germ cells with each differentiation state represented (Figure 4B). The epididymis contained morphologically mature sperm at similar concentrations to control littermates (Figure 4C). Ablated males produced normal numbers of litters and pups, suggesting the observed sperm functioned normally. In sum, these observations demonstrate Adar is neither the testicular RNA-editing enzyme nor is required for normal male germ cell development.

Figure 4.

A-to-I RNA editing and fertility in germ cell and Sertoli cell Adar ablation models. (A) Sanger sequencing detection of known RNA-editing sites. Asterisks—editing sites. (B) Adult testis and epididymal histology. (C) Sperm counts, total number of liters, and total number of pups. N = 4, error—standard deviation. Del – AdarDelete, Fl – AdarFl.

Testicular RNA editing is catalyzed by ADARB1

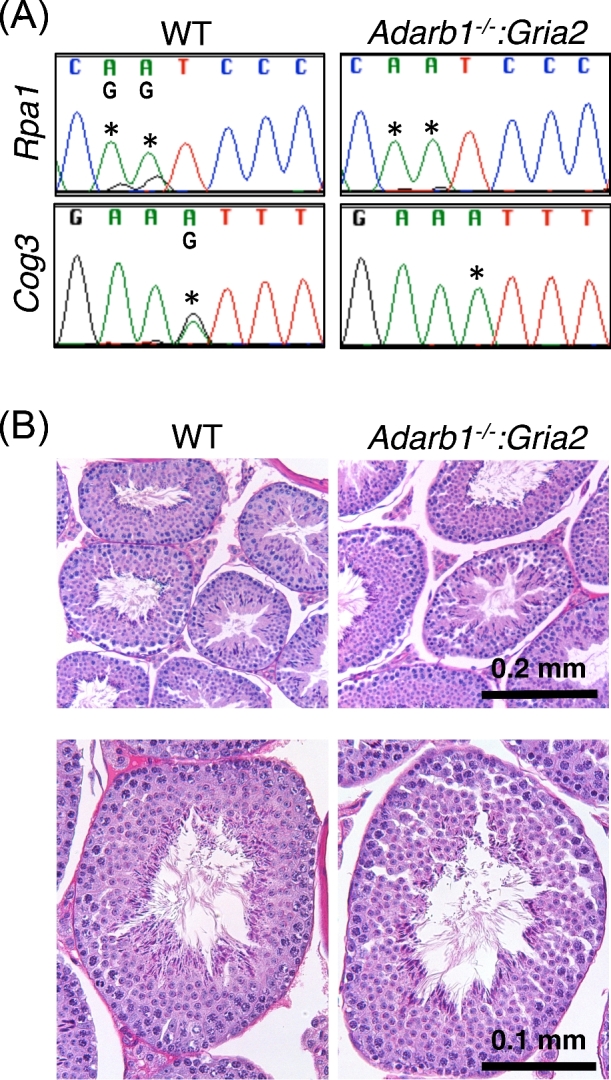

ADARB1 has been shown to be required for a very limited number of RNA-editing events, primarily in brain [16]. Global loss of Adarb1 results in perinatal lethality, however rescue of this phenotype by mutation at a single genomic site (Gria2) generates animals with normal lifespans and reportedly normal fertility. To more closely assess the impact of global ADARB1 loss on male germ cell biology, we assessed RNA editing at the known testis-editing sites in adult Adarb1-KO, Gria2-rescue (Adarb1-/-:Gria2) testes. These assays showed complete loss of RNA editing at known testis-edited sites with ADARB1 loss (Figure 5A), demonstrating ADARB1 is the active RNA-editing enzyme in the testis. However, histopathological analysis demonstrated this loss had no detectible impact on male germ cell development (Figure 5B). This observation is in agreement with previous observations suggesting ADARB1 loss has no appreciable impact on male fertility [16,26]. Taken together, these data show that while RNA editing does occur in the testis and is mediated by ADARB1, it is dispensable for normal male germ cell development.

Figure 5.

Testis RNA editing and histology in Adarb1 mutants. (A) Sanger sequencing detection of known RNA-editing sites. Asterisks—editing sites. (B) Adult testis histology. N = 3. WT—wildtype.

Discussion

A-to-I RNA editing can have profound impacts on the function of RNA. Male germ cells are particularly sensitive to perturbations of post-transcriptional regulation, and yet, no systematic analysis of the prevalence of or requirement for A-to-I RNA editing in male germ cells had been previously undertaken. To address this shortcoming, computational identification of RNA-editing events in whole testis and isolated germ cells was used to define potential male germ cell A-to-I editing events. Of the defined events, only a few were deemed genuine upon molecular and biochemical confirmation, and of these, all displayed a distinct cell-type dependent editing efficiency. This predominantly meiotic and postmeiotic cell-type dependent editing was not directly correlated to RNA-editing enzyme expression, nor the levels of the mRNAs being edited. Both known A-to-I RNA-editing enzymes were readily detectible in the testis. However, only ADARB1, normally associated with neural A-to-I RNA editing, was shown to drive the detected RNA-editing events. In spite of these findings, no direct impact on male fertility was observed in ADARB1 mutant models, leading to the question of why so few RNA-editing events are detected in the testis and the potential role of RNA-editing enzymes in male germ cell biology.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest RNA editing is dynamically regulated in the male germ cell in a manner unlike that reported for other tissues and cell types. In previous tissue-specific editing analyses, target RNA expression was the primary determinate of RNA-editing target selection within a tissue [22], while genetic analysis in a diverse outbred mouse population suggests local RNA structure is the primary factor regulating efficiency [27]. For the few editing events detected in the male germ cell there was no apparent correlation between target abundance and editing efficiency. Additionally, the level of ADAR enzyme expression has been correlated to the amount of overall RNA editing observed in a tissue [28], and yet the testis has an extremely low number of detectible RNA editing sites in spite of Adar expression levels similar to tissues with many editing events such as the liver, heart, and lung [22]. The low frequency of confirmable RNA-editing events in the testis may be due to pseudogene or retrogene expression that would generate confounding results for both the computational identification and molecular confirmation analyses. Alternatively, RNA-editing events in the testis may occur at a normal frequency across the transcriptome, but with substantially reduced efficiency or in only a subset of individuals. The latter interpretation is supported by the observation that the number of RNA-editing sites detected by our computational method increases dramatically with either reduction of the efficiency threshold or relaxation of the biological replicate criteria. Taken together, these observations suggest additional regulatory mechanisms at play in the male germ cell that repress A-to-I editing. Previous reports have suggested that a second AD domain-containing protein, ADAD1 (previously known as TENR), may serve this function in postmeiotic germ cells [29]. Mutation of Adad1 has profound impacts on postmeiotic germ cell development [30], but whether it has a direct impact on RNA editing in this cell population remains unknown.

Despite the expression of both ADAR and ADARB1 in the male germ cell, there is an apparent paucity of editing events, leading to the question of their potential roles in germ cell biology. RNA editing of a target rarely impacts the entire population of molecules, making it a unique mechanism for generating novel variants without the potentially deleterious cost of genomic mutation. As such, it has been proposed that RNA editing is a powerful mechanism for adaptive evolution in higher animals [6]. It has already been proposed that the male germ cell is a potent site for testing novel DNA variants due in part to the unusually high-selective pressures on male germ cells [31], a notion supported by recent analysis of cross species expression [21,32]. Expression of ADAR and ADARB1 in male germ cells may provide an additional mechanism for variant testing on the RNA level, generating a small number of random variants. As this process would likely be stochastic and rare, particularly in an inbred mouse population as studied here, the stringent parameters used for RNA-editing event identification would be unlikely to detect it.

In addition to their potential to drive adaptive evolution, both ADAR and ADARB1 have been implicated in regulating viral response [33,34]. ADAR is generally considered the primary RNA-editing enzyme responsible for viral response as both isoforms may be induced by viral infection [35,36]. Mechanistically, ADARs impact viral infection by either modulating the cellular response to infection or directly editing viral RNAs. It has been known for several decades that viral RNAs may undergo either site-specific or more extensive A-to-I editing [37], and these events are driven by one or both ADAR enzymes. Multiple viruses are known to be direct targets of ADAR regulation, including cytomegalovirus [35] and human immunodeficiency virus [38], both of which have been reported as capable of directly infecting male germ cells [39,40]. It is feasible that a continuous, low level of ADAR expression in the male germ cell acts as a protective mechanism against viral infection, which may negatively impact spermatogenesis and offspring health. Whether ADAR(s) in the germ cell are responsive to viral infection as in other systems, or targets other known or emerging viruses that infect germ cells, remains to be explored.

The role of A-to-I RNA editing and the enzymes that catalyze it appear to be relatively minor in steady-state spermatogenesis in a laboratory setting. However, the abundant and cell-type dependent expression of the two known catalytically active RNA-editing enzymes suggests mechanisms of RNA-editing regulation not found in other tissues. In addition, the expression and apparent low levels of both ADAR and ADARB1 activity suggest other possibly important roles for RNA editing outside the minimally challenging laboratory setting. Further study will be needed to clarify whether RNA editing or the editing enzymes themselves play a role in either adaptive evolution or viral response in the male germ cell.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at BIOLRE online.

Supplemental Figure 1. Cell-type dependent expression of RNA-editing target genes by RNA-sequencing analysis. N = 3/cell type.

Supplementary data are available at BIOLRE online.

Supplemental Figure 1. Cell-type dependent expression of RNA-editing target genes by RNA-sequencing analysis. N = 3/cell type.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Michael Jantsch of the Medical University of Vienna for kindly providing Adarb1:Gria2 tissue samples and critical reading of this manuscript.

References

- 1. Gu T, Buaas FW, Simons AK, Ackert-Bicknell CL, Braun RE, Hibbs MA. Canonical A-to-I and C-to-U RNA editing is enriched at 3'UTRs and microRNA target sites in multiple mouse tissues. PLoS One 2012; 7:e33720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sommer B, Kohler M, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH. RNA editing in brain controls a determinant of ion flow in glutamate-gated channels. Cell 1991; 67:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Savva YA, Rezaei A, St Laurent G, Reenan RA. Reprogramming, circular reasoning and self versus non-self: one-stop shopping with RNA editing. Front Genet 2016; 7:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nishikura K. Functions and regulation of RNA editing by ADAR deaminases. Annu Rev Biochem 2010; 79:321–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mannion NM, Greenwood SM, Young R, Cox S, Brindle J, Read D, Nellaker C, Vesely C, Ponting CP, McLaughlin PJ, Jantsch MF, Dorin J et al. . The RNA-editing enzymeADAR1 controls innate immune responses to RNA. Cell Rep 2014; 9:1482–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gommans WM, Mullen SP, Maas S. RNA editing: a driving force for adaptive evolution? Bioessays 2009; 31:1137–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Slavov D, Clark M, Gardiner K. Comparative analysis of the RED1 and RED2 A-to-I RNA editing genes from mammals, pufferfish and zebrafish. Gene 2000; 250:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Slavov D, Crnogorac-Jurcevic T, Clark M, Gardiner K. Comparative analysis of the DRADA A-to-I RNA editing gene from mammals, pufferfish and zebrafish. Gene 2000; 250:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen CX, Cho DS, Wang Q, Lai F, Carter KC, Nishikura K. A third member of the RNA-specific adenosine deaminase gene family, ADAR3, contains both single- and double-stranded RNA binding domains. RNA 2000; 6:755–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang Q, Khillan J, Gadue P, Nishikura K. Requirement of the RNA editing deaminase ADAR1 gene for embryonic erythropoiesis. Science 2000; 290:1765–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feng Y, Sansam CL, Singh M, Emeson RB. Altered RNA editing in mice lacking ADAR2 autoregulation. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26:480–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Athanasiadis A, Rich A, Maas S. Widespread A-to-I RNA editing of Alu-containing mRNAs in the human transcriptome. PLoS Biol 2004; 2:e391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Enstero M, Akerborg O, Lundin D, Wang B, Furey TS, Ohman M, Lagergren J. A computational screen for site selective A-to-I editing detects novel sites in neuron specific Hu proteins. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levanon EY, Eisenberg E, Yelin R, Nemzer S, Hallegger M, Shemesh R, Fligelman ZY, Shoshan A, Pollock SR, Sztybel D, Olshansky M, Rechavi G et al. . Systematic identification of abundant A-to-I editing sites in the human transcriptome. Nat Biotechnol 2004; 22:1001–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang Q, Miyakoda M, Yang W, Khillan J, Stachura DL, Weiss MJ, Nishikura K. Stress-induced apoptosis associated with null mutation of ADAR1 RNA editing deaminase gene. J Biol Chem 2004; 279:4952–4961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higuchi M, Maas S, Single FN, Hartner J, Rozov A, Burnashev N, Feldmeyer D, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH. Point mutation in an AMPA receptor gene rescues lethality in mice deficient in the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR2. Nature 2000; 406:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soumillon M, Necsulea A, Weier M, Brawand D, Zhang X, Gu H, Barthes P, Kokkinaki M, Nef S, Gnirke A, Dym M, de Massy B et al. . Cellular source and mechanisms of high transcriptome complexity in the mammalian testis. Cell Rep 2013; 3:2179–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ramaswami G, Zhang R, Piskol R, Keegan LP, Deng P, O’Connell MA, Li JB. Identifying RNA editing sites using RNA sequencing data alone. Nat Methods 2013; 10:128–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sakurai M, Suzuki T. Biochemical identification of A-to-I RNA editing sites by the inosine chemical erasing (ICE) method. Methods Mol Biol 2011; 718:89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Snyder EM, Small C, Griswold MD. Retinoic acid availability drives the asynchronous initiation of spermatogonial differentiation in the mouse. Biol Reprod 2010; 83:783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Soumillon M, Necsulea A, Weier M, Brawand D, Zhang X, Gu H, Barthes P, Kokkinaki M, Nef S, Gnirke A, Dym M, de Massy B et al. . Cellular source and mechanisms of high transcriptome complexity in the mammalian testis. Cell Rep 2013; 3:2179–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huntley MA, Lou M, Goldstein LD, Lawrence M, Dijkgraaf GJ, Kaminker JS, Gentleman R. Complex regulation of ADAR-mediated RNA-editing across tissues. BMC Genomics 2016; 17:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pickrell JK, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. Comment on "Widespread RNA and DNA sequence differences in the human transcriptome". Science 2012; 335:1302; author reply 1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Patterson JB, Samuel CE. Expression and regulation by interferon of a double-stranded-RNA-specific adenosine deaminase from human cells: evidence for two forms of the deaminase. Mol Cell Biol 1995; 15:5376–5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bao J, Ma HY, Schuster A, Lin YM, Yan W. Incomplete cre-mediated excision leads to phenotypic differences between Stra8-iCre; Mov10l1(lox/lox) and Stra8-iCre; Mov10l1(lox/Delta) mice. Genesis 2013; 51:481–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Horsch M, Seeburg PH, Adler T, Aguilar-Pimentel JA, Becker L, Calzada-Wack J, Garrett L, Gotz A, Hans W, Higuchi M, Holter SM, Naton B et al. . Requirement of the RNA-editing Enzyme ADAR2 for Normal Physiology in Mice. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:18614–18622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gu T, Gatti DM, Srivastava A, Snyder EM, Raghupathy N, Simecek P, Svenson KL, Dotu I, Chuang JH, Keller MP, Attie AD, Braun RE et al. . Genetic architectures of quantitative variation in RNA editing pathways. Genetics 2016; 202:787–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Picardi E, Manzari C, Mastropasqua F, Aiello I, D’Erchia AM, Pesole G. Profiling RNA editing in human tissues: towards the inosinome Atlas. Sci Rep 2015; 5:14941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schumacher JM, Lee K, Edelhoff S, Braun RE. Distribution of Tenr, an RNA-binding protein, in a lattice-like network within the spermatid nucleus in the mouse. Biol Reprod 1995; 52:1274–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Connolly CM, Dearth AT, Braun RE. Disruption of murine Tenr results in teratospermia and male infertility. Dev Biol 2005; 278:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kaessmann H. Origins, evolution, and phenotypic impact of new genes. Genome Res 2010; 20:1313–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brawand D, Soumillon M, Necsulea A, Julien P, Csardi G, Harrigan P, Weier M, Liechti A, Aximu-Petri A, Kircher M, Albert FW, Zeller U et al. . The evolution of gene expression levels in mammalian organs. Nature 2011; 478:343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ward SV, George CX, Welch MJ, Liou LY, Hahm B, Lewicki H, de la Torre JC, Samuel CE, Oldstone MB. RNA editing enzyme adenosine deaminase is a restriction factor for controlling measles virus replication that also is required for embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108:331–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Doria M, Tomaselli S, Neri F, Ciafre SA, Farace MG, Michienzi A, Gallo A. ADAR2 editing enzyme is a novel human immunodeficiency virus-1 proviral factor. J Gen Virol 2011; 92:1228–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nachmani D, Zimmermann A, Oiknine Djian E, Weisblum Y, Livneh Y, Khanh Le VT, Galun E, Horejsi V, Isakov O, Shomron N, Wolf DG, Hengel H et al. . MicroRNA editing facilitates immune elimination of HCMV infected cells. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10:e1003963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. George CX, Wagner MV, Samuel CE. Expression of interferon-inducible RNA adenosine deaminase ADAR1 during pathogen infection and mouse embryo development involves tissue-selective promoter utilization and alternative splicing. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:15020–15028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Samuel CE. Adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs) are both antiviral and proviral. Virology 2011; 411:180–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Doria M, Neri F, Gallo A, Farace MG, Michienzi A. Editing of HIV-1 RNA by the double-stranded RNA deaminase ADAR1 stimulates viral infection. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37:5848–5858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Naumenko VA, Tyulenev YA, Yakovenko SA, Kurilo LF, Shileyko LV, Segal AS, Zavalishina LE, Klimova RR, Tsibizov AS, Alkhovskii SV, Kushch AA. Detection of human cytomegalovirus in motile spermatozoa and spermatogenic cells in testis organotypic culture. Herpesviridae 2011; 2:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Muciaccia B, Filippini A, Ziparo E, Colelli F, Baroni CD, Stefanini M. Testicular germ cells of HIV-seropositive asymptomatic men are infected by the virus. J Reprod Immunol 1998; 41:81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data are available at BIOLRE online.

Supplemental Figure 1. Cell-type dependent expression of RNA-editing target genes by RNA-sequencing analysis. N = 3/cell type.