Cabozantinib (cabo) inhibits tyrosine kinases including MET and VEGFR2. In this phase I trial in heavily pretreated patients with renal cell cancer (RCC), cabo treatment resulted in a 28% response rate and median progression-free survival of 12.9 months, with a safety profile similar to other multitargeted VEGFR inhibitors. These results warrant further investigation of cabo in RCC.

Keywords: clinical trial, c-Met, VEGFR-2, receptor tyrosine kinase, renal cancer

Abstract

Background

Cabozantinib targets tyrosine kinases including the hepatocyte growth factor receptor (MET) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 2, which are important drug targets in renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

Patients and methods

This single-arm open-label phase I trial evaluated the safety and tolerability of cabozantinib in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic clear cell RCC.

Results

The study enrolled 25 RCC patients for whom standard therapy had failed. Patients received a median of two prior systemic agents, and most patients had previously received at least one VEGF pathway inhibiting therapy (22 patients [88%]). Common adverse events included fatigue, diarrhea, nausea, proteinuria, appetite decreased, palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia, and vomiting. Partial response was reported in seven patients (28%). Median progression-free survival was 12.9 months, and median overall survival was 15.0 months.

Conclusion

Cabozantinib demonstrates preliminary anti-tumor activity and a safety profile similar to that seen with other multitargeted VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced RCC patients. Further evaluation of cabozantinib in RCC is warranted.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier

introduction

Cabozantinib is a small molecule inhibitor of tyrosine kinases including the hepatocyte growth factor receptor (MET) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), which are important mediators of tumor cell survival, metastasis, and tumor angiogenesis [1]. In clinical studies, cabozantinib has demonstrated activity in multiple tumor types, with responses observed both in soft tissue disease and in bone metastases [2, 3].

Clear cell RCC tumors commonly contain mutations in the von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene, resulting in increased expression of MET and VEGF, and concomitant increases in tumor angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and invasive growth [4, 5]. High MET expression is associated with poor pathologic features (higher Fuhrman grade and more advanced disease stage) and poor prognosis in RCC [6], and VHL-deficient RCC cells have been shown to be more sensitive to MET targeting than their counterparts in which VHL function has been restored [7]. Also, circulating proteases that positively or negatively regulate activation of the MET ligand, hepatocyte growth factor, are frequently upregulated or downregulated, respectively, in RCC [4].

VEGF pathway inhibitors are approved for use in metastatic RCC, but a substantial percentage of patients (9%–25%) demonstrate primary disease refractoriness to first-line anti-VEGF pathway therapy [8]. In patients who respond to these agents, acquired resistance almost invariably arises [8]. In preclinical models and some clinical studies, acquired resistance to VEGF pathway inhibitors has been shown to be associated with upregulation of alternative proangiogenic and proinvasive signaling pathways, including the MET pathway [9–11]. Thus, targeting the VEGF and MET signaling pathways simultaneously may provide advantages over targeting the VEGF pathway alone, and therefore warrants investigation in RCC.

As MET and VEGFR2 are implicated in RCC progression, this phase I study assessed the safety and tolerability of cabozantinib, which targets these pathways simultaneously, in patients with advanced RCC. Tumor response, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) were also assessed. The study also included a drug–drug interaction analysis of cabozantinib with rosiglitazone, a substrate for CYP2C8, to support a New Drug Application filing for cabozantinib dosed at 140 mg daily. In this report, we present the safety and efficacy data from the RCC patients enrolled in the study (drug–drug interaction and pharmacokinetics results will be published separately).

methods

patients

Adult patients with histologically confirmed metastatic RCC (with a clear cell component) were enrolled; tumors were refractory or had progressed following standard therapies and were measurable per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST, version 1.0) [12]. All patients had adequate bone marrow function and a Karnofsky performance score ≥70 [Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score ≤2]. Patients were ineligible if they had coagulation parameters (prothrombin time/international normalized ratio or partial thromboplastin time) ≥1.5 times the upper limit of normal, were deemed at risk for gastrointestinal perforation or fistula formation, or had received radiotherapy within 14 days, cytotoxic chemotherapy within 28 days, prior tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) or hormonal therapy within the longer of 14 days or 5 half-lives, or investigational agents within the shorter of 28 days or 5 half-lives before the first dose of study treatment. Patients were also ineligible if they were undergoing treatment with drugs known to be extensively metabolized by CYP2C8, inhibitors of CYP3A4 or CYP2C8 (including warfarin or other coumarin derivatives), or inducers of CYP3A isozymes. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each study center and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients provided written informed consent according to institutional guidelines.

study design

Patients received a single dose of the CYP2C8 substrate rosiglitazone on day 1 (for the drug–drug interaction portion of the study) and began daily oral dosing of 140 mg cabozantinib on day 2. On day 22, patients who had not experienced an interruption in cabozantinib dosing or a reduction below 100 mg/day received a second dose of rosiglitazone. From day 24 onward, patients continued to receive, at the discretion of the investigator, daily cabozantinib until progressive disease (PD) or unacceptable adverse events (AEs), or patient withdrawal of consent. Treatment compliance was monitored through records of drug dispensing and return.

safety and efficacy assessments

Safety assessments, including the evaluation of AEs, vital signs, electrocardiogram, laboratory tests, and concomitant medications, were conducted on days 1, 2, 7, 15, 21, 22, and 57, then every 4 weeks through week 49, and every 8 weeks thereafter. AEs were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0. Study treatment was withheld in the event of absolute neutrophil count <1000/mm3, platelet count <50 000/mm3, grade 4 anemia, intolerable grade 2 toxicity, or any grade ≥3 toxicity. If the patient recovered within 6 weeks and toxicity was deemed unrelated to study treatment, treatment was restarted at the same dose. If the patient recovered within 6 weeks and toxicity was deemed possibly related to study treatment, drug treatment was restarted at a reduced dose, and could be re-escalated, except for cases of neutropenia or thrombocytopenia. Patients who did not recover within 6 weeks discontinued study treatment.

Tumor response by MRI or CT scan was investigator-assessed using RECIST 1.0 at screening, at day 64 (±4 days), and every 8 weeks thereafter until documented PD per RECIST, death, or initiation of subsequent anticancer therapy. Response was confirmed by repeat imaging at least 4 weeks after the initial assessment. For the analysis of OS and PFS from the first cabozantinib dose, the Kaplan–Meier method was employed to estimate medians.

results

patients

Twenty-five patients from four US centers were enrolled (Table 1). Patients had received a median number of two prior systemic agents: 22 patients (88%) had previously received at least one VEGF pathway inhibiting therapy, and 15 patients (60%) had received an inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). Based on the Heng prognostic model, which categorizes patients treated with first- and second-line targeted therapies into risk prognosis groups, the majority of patients (80%) fell into the intermediate-risk category, with two patients (8%) in the poor risk category and three patients (12%) in the good risk category [13].

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline disease characteristics (N = 25)

| Median age, years (range) | 61 (41–79) |

| Sex, n | |

| Male | 21 |

| Female | 4 |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |

| 0 | 20 (80) |

| 1 | 4 (16) |

| 2 | 1 (4) |

| Median number of prior agents, n | 2 |

| Prior systemic agents, n (%) | |

| 0 | 0 (0) |

| 1 | 8 (32) |

| 2 | 6 (24) |

| 3 | 3 (12) |

| ≥4 | 8 (32) |

| Prior anticancer therapies, n (%) | |

| Prior anti-VEGF therapy | 22 (88) |

| Prior mTOR inhibitor therapy | 15 (60) |

| Prior anti-VEGF + mTOR inhibitor therapy | 13 (52) |

| Prior cytokine therapy | 5 (20) |

| Prior chemotherapy | 3 (12) |

| Patients with bone metastases, n (%) | 4 (16)a |

aOne of the four RCC patients with bone metastases at baseline was followed by bone scan.

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

safety

The most frequently reported non-laboratory grade 3 AEs, regardless of causality, were fatigue (20%) and diarrhea (12%) (Table 2). Other grade 3 AEs reported included decreased appetite (4%), hypertension (4%), palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia (PPE) (4%), and vomiting (4%). Three non-laboratory grade 4 events were reported in four patients including three events (12%) of pulmonary embolism (PE): one patient had a PE (deemed related to cabozantinib) followed by a peritoneal hemorrhage (deemed unrelated to cabozantinib, and associated with low-molecular-weight heparin treatment and progression of hepatic metastases), two patients had a PE (deemed related or possibly related to cabozantinib), and one patient had a mental status change (deemed unrelated to cabozantinib, and associated with hyponatremia and the presence of brain metastases).

Table 2.

Most frequently reported adverse events, regardless of causality, in ≥8 patients

| Adverse eventa | All grades, n (%) | Grade ≥3, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigueb | 20 (80) | 5 (20) |

| Diarrheab | 16 (64) | 3 (12) |

| Hypophosphatemiac | 15 (60) | 10 (40) |

| Hypothyroidism | 12 (48) | 0 |

| Nausea | 11 (44) | 0 |

| Lipase increased | 10 (40) | 3 (12) |

| Hypomagnesemia | 10 (40)c | 0 |

| Proteinuria | 9 (36) | 2 (8) |

| Appetite decreased | 9 (36) | 1 (4) |

| Palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesiab,d | 9 (36) | 1 (4) |

| Vomiting | 9 (36) | 1 (4) |

| Hyponatremia | 8 (32)e | 5 (20) |

| Dyspnea | 8 (32) | 0 |

| Adverse event of interest | ||

| Hypertension | 8 (32) | 1 (4) |

aMedical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities v. 14.1 preferred terms (converted to American English spelling), Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v. 3.0 grading; n = number of patients with event.

bGroupings of preferred terms related to a particular medical condition.

cDid not result in a dose reduction nor in discontinuation. Two subjects were dose-interrupted due to hypophosphatemia.

dHand–foot syndrome.

eResulted in dose reduction in one patient.

Increased levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone occurred in 17 patients. Twelve patients had hypothyroidism, but none were grade 3 or higher (Table 2). No patients had a clinically significant abnormal ECG during study treatment.

AEs were listed as the primary reason for treatment discontinuation in 24% of patients. Dose reductions occurred in 20 of 25 patients: the final dose listed was 100 mg for 6 patients, 60 mg for 11 patients, 40 mg for 2 patients, and 20 mg for 1 patient. The median average daily dose was 75.5 mg cabozantinib (range, 43.8–137.5 mg), and the median dose intensity percentage was 53.9% (range, 31.3%–98.2%).

efficacy

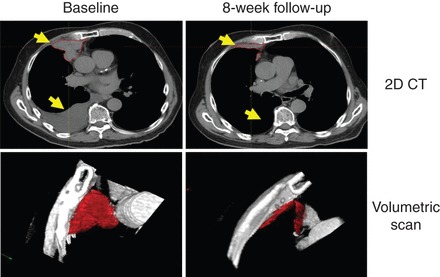

Seven patients (28%) had a partial response (PR), including a patient with sarcomatoid differentiation on histology who was previously treated with sunitinib, gemcitabine, and everolimus (Figure 1). Five of the patients who experienced a PR were previously treated with two or more systemic therapies; three of these patients had received 2–4 prior systemic therapies, and two patients had received >4 prior systemic therapies. Among the seven patients who had responses, two patients were dose-reduced to 100 mg and five patients were dose-reduced to 60 mg.

Figure 1.

Radiographic response in a patient with sarcomatoid differentiation. Prior therapies included sunitinib, gemcitabine, and everolimus.

Thirteen patients (52%) had stable disease as their best response, and only one patient (4%) showed evidence of primary refractory disease with PD as their best response. The duration of response ranged from 1.7 to ≥16.6 months; the median duration of response has not yet been reached.

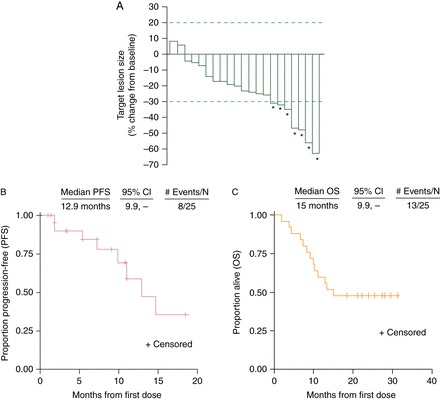

Nineteen of 21 assessable patients (90%) with ≥1 post-baseline scan experienced tumor regression (Figure 2A); post-baseline tumor assessments were not available in four patients who discontinued study treatment before the first scheduled post-baseline assessment. The median PFS was 12.9 months with a median follow-up of 14.7 months (range, 11.2–21.8 months) (Figure 2B). Median OS was 15.0 months with a median follow-up of 28.3 months (range, 24.8–35.5 months) (Figure 2C). Clinical activity against metastatic lesions in bone was observed in some patients (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 2.

(A) Best target lesion change in patients with ≥1 post-baseline scan. Stable disease per RECIST is represented by the space between the dotted lines. Asterisks indicate a confirmed partial response. (B) Progression-free survival. (C) Overall survival.

discussion

Anticancer therapies targeting the VEGF signaling pathway have extensively been evaluated in patients with RCC, and these therapies now play an important role in the treatment of many of these patients. However, patients treated with these agents eventually experience disease progression and therefore need additional treatment options. Compelling evidence for a role for MET in the disease pathophysiology and in the development of resistance to therapies targeting the VEGF signaling pathway makes cabozantinib an attractive candidate for evaluation in RCC. Therefore, we utilized a drug–drug interaction study of cabozantinib in cancer patients as an opportunity for such an assessment.

In this study, treatment with cabozantinib generally yielded a safety profile similar to that seen with other VEGFR TKIs in RCC patients [14–17]. The most common non-laboratory AEs regardless of causality were fatigue, diarrhea, nausea, decreased appetite, and PPE. The incidence of PPE in this study was 36% (all grades) or 4% (grade 3 or higher). This rate of PPE is lower than was observed in a phase III trial of cabozantinib in medullary thyroid cancer (MTC; 50%/13%) [18], and is comparable to or lower than the rates observed with four other TKIs in phase III studies in RCC [16, 17].

Hypertension, a common cardiovascular AE of anti-angiogenic drugs, was reported in 32% (all grades) or 4% (grade 3 or higher) of patients. These rates are comparable to or lower than those reported with other agents targeting VEGFR [14–17], potentially indicating that VEGFR inhibition (and thus VEGFR-dependent clinical efficacy) may not have been maximal in this study. However, only 25 patients contributed to the safety analysis in this study, whereas larger trials of cabozantinib in MTC and castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) [3, 18] showed hypertension and other AEs occurring at rates that are more consistent with other VEGFR inhibitors in RCC [14–17]. PE was observed in three patients (12%) in this study, and also has been observed in clinical studies with cabozantinib in CRPC (7%–11%) and MTC (2.3%) [3, 18, 19]. In addition, PE has been observed in heavily pretreated RCC patients in other studies [20, 21]. Importantly, ongoing phase II and III studies will characterize cabozantinib's AE profile in larger populations of RCC patients.

Cabozantinib demonstrated clinical activity in heavily pretreated RCC patients, with a response rate of 28% and median PFS of 12.9 months. Other anti-angiogenic TKIs have also demonstrated activity in RCC patients who were previously exposed to at least one line of therapy. For example, in second-line RCC patients previously treated with sunitinib, response rates of 19% and 9% and median PFS of 6.7 and 4.7 months were observed with axitinib and sorafenib, respectively [17]. In the RECORD-1 trial, which compared the mTOR inhibitor everolimus to placebo in patients who had progressed on sorafenib and/or sunitinib, median PFS for the everolimus arm was 4.9 versus 1.9 months for the placebo arm [22]. And in the recently reported GOLD trial comparing dovitinib and sorafenib in third-line RCC patients, response rates of 4% in each arm and median PFS of 3.6–3.7 months were observed [23]. Thus, the tumor response and PFS results with cabozantinib are noteworthy, particularly given that the patient population was heavily pretreated.

The median overall survival observed in this study was 15 months which, given the median PFS of 12.9 months, may generally imply a period of ∼2 months between progression and death. Notwithstanding any caveats in comparing these two medians (such as small sample size and potential for selection bias), we speculate that a two-month period between progression and death, if accurate, likely reflects the advanced disease in these patients, most of whom had received multiple systemic therapies before treatment with cabozantinib. PFS and OS will be prospectively and more precisely assessed in larger randomized trials of cabozantinib, including a phase II trial (versus sunitinib) in first-line RCC patients (NCT01835158) and a phase III trial (versus everolimus) in RCC patients who progressed after at least one prior VEGFR TKI therapy (NCT01865747).

Bone metastases are a frequent complication for RCC patients [24], but are often resistant to anti-angiogenic treatment [25]. Both the MET and VEGF signaling pathways appear to be important in regulating the functions of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, two key cell types in the bone microenvironment that are involved in the development of metastatic bone lesions [26]. In non-clinical studies, blockade of the development of both osteoblastic and osteolytic features of tumor xenografts implanted in bone was observed in response to cabozantinib therapy [27, 28]. Post hoc results of bone scan resolution and pain relief anecdotes have previously been reported with cabozantinib in CRPC and metastatic breast cancer patients in phase I and phase II studies [3, 29, 30]. Based on those results, and related anecdotal observations in this study, the effects of cabozantinib on bone metastases are being prospectively assessed in RCC patients in a recently initiated phase III trial (NCT01865747).

The initial daily dose of cabozantinib in this study was 140 mg and was selected to support the drug–drug interaction end point of the trial based on the maximum-tolerated dose determined in the initial phase I study [2]. However, the majority of patients in the current trial were subsequently dose-reduced to manage tolerability. Based on the long-term tolerability and clinical activity associated with doses of cabozantinib <140 mg in this and other trials [3, 19, 29, 30], 60 mg daily has been selected as the starting dose in many ongoing or planned trials.

In conclusion, the safety profile and anti-tumor activity we have observed with cabozantinib in heavily pretreated RCC patients, most of whom had received prior therapies targeting the VEGF signaling pathway, warrant further investigation in this tumor type.

funding

This clinical trial was supported by Exelixis, Inc. Additional funding was provided by the Trust family, Loker Pinard, and Michael Brigham funds for Kidney Cancer Research (TKC) and the DF/HCC SPORE in Kidney Cancer (TKC, DFM).

disclosure

T.C., S.P., D.M., S.M., and J.D. have conducted research sponsored by Exelixis. T.C. and D.M. have received consultancy fees from Exelixis. J.H. and K.F. are fulltime employees and shareholders of Exelixis.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We thank the study medical monitor David Ramies (Exelixis, Inc.); Frauke Schimmoller, Teresa Rafferty, Colin Hessel, Yihua Lee, and Jeffrey Zhang (Exelixis, Inc.) who assisted greatly in data management and analysis; Dana Aftab and Gisela Schwab (Exelixis, Inc.) for their critical review of the manuscript; and Becky Norquist for medical writing support.

references

- 1.Yakes FM, Chen J, Tan J, et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:2298–2308. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurzrock R, Sherman SI, Ball DW, et al. Activity of XL184 (cabozantinib), an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2660–2666. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith DC, Smith MR, Sweeney C, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced prostate cancer: results of a phase II randomized discontinuation trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:412–419. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giubellino A, Linehan WM, Bottaro DP. Targeting the Met signaling pathway in renal cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:785–793. doi: 10.1586/era.09.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rini BI. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma: many treatment options, one patient. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3225–3234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibney GT, Aziz SA, Camp RL, et al. c-Met is a prognostic marker and potential therapeutic target in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:343–349. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bommi-Reddy A, Almeciga I, Sawyer J, et al. Kinase requirements in human cells: III. Altered kinase requirements in VHL−/− cancer cells detected in a pilot synthetic lethal screen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16484–16489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806574105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heng DY, Xie W, Bjarnason GA, et al. Primary anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-refractory metastatic renal cell carcinoma: clinical characteristics, risk factors, and subsequent therapy. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1549–1555. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shojaei F, Lee JH, Simmons BH, et al. HGF/c-Met acts as an alternative angiogenic pathway in sunitinib-resistant tumors. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10090–10100. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebos JM, Kerbel RS. Antiangiogenic therapy: impact on invasion, disease progression, and metastasis. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:210–221. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.21. Erratum in: Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011; 8: 316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sennino B, Ishiguro-Oonuma T, Wei Y, et al. Suppression of tumor invasion and metastasis by concurrent inhibition of c-Met and VEGF signaling in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:270–287. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. External validation and comparison with other models of the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic model: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:141–148. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70559-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alpha in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3584–3590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:722–731. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rini RJ, Escudier B, Tomczak P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1931–1939. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61613-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elisei R, Schlumberger MJ, Müller SP, et al. Cabozantinib in progressive medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3639–3646. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith MR, Sweeney C, Corn PG, et al. Cabozantinib in chemotherapy-pretreated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: results of a phase II non-randomized expansion study. J Clin Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.5954. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amato RJ, Flaherty AL, Stepankiw M. Phase I trial of everolimus plus sorafenib for patients with advanced renal cell cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2012;10:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellmunt J, Trigo JM, Calvo E, et al. Activity of a multitargeted chemo-switch regimen (sorafenib, gemcitabine, and metronomic capecitabine) in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a phase 2 study (SOGUG-02-06) Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:350–357. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70383-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. RECORD-1 Study Group. Phase 3 trial of everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results and analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer. 2010;116:4256–4265. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motzer RJ, Porta C, Vogelzang NJ. Dovitinib versus sorafenib for third-line targeted treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:286–296. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70030-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6243s–6249s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beuselinck B, Oudard S, Rixe O, et al. Negative impact of bone metastasis on outcome in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:794–800. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aftab DT, McDonald DM. MET and VEGF: synergistic targets in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2011;13:703–709. doi: 10.1007/s12094-011-0719-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen HM, Ruppender N, Zhang X, et al. Cabozantinib inhibits growth of androgen-sensitive and castration-resistant prostate cancer and affects bone remodeling. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai J, Zhang H, Karatsinides A, et al. Cabozantinib inhibits prostate cancer growth and prevents tumor-induced bone lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:617–630. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tolaney SM, Nechushtan H, Berger R, et al. Cabozantinib (XL184) in patients with metastatic breast cancer: results from a phase 2 randomized discontinuation trial. Cancer Res. 2011;71(24):3s. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee RJ, Saylor PJ, Michaelson MD, et al. A dose-ranging study of cabozantinib in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3088–3094. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.