Untargeted metabolomics of breath samples was performed for pediatric patients in Malawi with and those without malaria. A combination of 6 breath compounds could be used to diagnose malarial infection with 83% accuracy. Additionally, infection corresponded with higher levels of 2 mosquito-attractant terpenes.

Keywords: Malaria, breath, volatile organic compounds, terpenes, biomarkers

Abstract

Current evidence suggests that malarial infection could alter metabolites in the breath of patients, a phenomenon that could be exploited to create a breath-based diagnostic test. However, no study has explored this in a clinical setting. To investigate whether natural human malarial infection leads to a characteristic breath profile, we performed a field study in Malawi. Breath volatiles from children with and those without uncomplicated falciparum malaria were analyzed by thermal desorption–gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Using an unbiased, correlation-based analysis, we found that children with malaria have a distinct shift in overall breath composition. Highly accurate classification of infection status was achieved with a suite of 6 compounds. In addition, we found that infection correlates with significantly higher breath levels of 2 mosquito-attractant terpenes, α-pinene and 3-carene. These findings attest to the viability of breath analysis for malaria diagnosis, identify candidate biomarkers, and identify plausible chemical mediators for increased mosquito attraction to patients infected with malaria parasites.

(See the Editorial commentary by Fidock, on pages 1512–4.)

Malaria remains a critical global health concern that affects hundreds of millions of people each year [1]. The most deadly form, caused by the parasite Plasmodium falciparum, remains a particular burden throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Diagnostic testing for malaria is crucial for acute fever management in the clinic and also for public health campaigns aimed at monitoring and control [2]. Current clinical practice depends on the gold standard of microscopic examination of patient blood samples, with increasing use of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) based on a lateral flow format to detect parasite antigens [3, 4]. Both methods can achieve high accuracy rates but often face prohibitive cost and skill requirements in many malaria-endemic settings [3]. While RDTs demand fewer human and capital resources, a number of factors can lead to dramatically lower accuracy than microscopy [5]. Further, the most widespread RDTs, based on detection of the P. falciparum protein HRP2, have an intrinsic false-positive rate, as the parasite-derived antigen remains in the bloodstream up to a month after infection clearance [6]. Worryingly, false-negative results are now rising due to the spread of parasite populations lacking the HRP2 antigen in India, Peru, and Africa [7–12]. In some geographical regions, >20% of surveyed parasite infections already lack HRP2 [12]. In 2016, the World Health Organization put out a call for new test antigens in response to growing concerns about current RDTs [13].

By investigating the existence and extent of breath biomarkers for malaria, new avenues for diagnostics become possible. Any given exhaled human breath contains hundreds of different molecules, known as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) due to their ready partition into the gas phase, and thousands of breath VOCs have been described [14]. Breath-based diagnosis operates on the presumption that pathological conditions create characteristic and reproducible changes in breath VOCs, as has been reported for an increasing number of malignancies and infectious diseases [15–18]. Determining whether a given disease generates a unique, detectable breath VOC signature (ie, a “breathprint”) represents the first step in development of a breath-based diagnostic, which has the possibility to be noninvasive and easy to perform [19].

Preliminary studies indicate malaria could generate just such a breathprint. For example, a number of alterations in breath compounds were observed during experimental, sub-microscopic malaria in volunteers [20]. However, no study has yet investigated whether these or other patterns are observed in clinical malaria episodes, where the parasite burden is at least one thousand times higher, the infection has been present longer, and the sexual stage of the parasite has had time to develop. Additional evidence that malaria is a prime candidate for breath-based diagnosis comes from studies of mosquito behavior. The Plasmodium parasite requires Anopheles species vector mosquitoes to sustain transmission [3]. Studies in human, mouse, and avian malaria have repeatedly demonstrated increased mosquito attraction to odors from infected vertebrate hosts [21–25]. Thus, Plasmodium infection may alter host VOCs, which might then be detected in the breath.

To evaluate for P. falciparum–specific changes in breath volatiles during natural human malarial infection, we performed unbiased breathprinting. We collected and analyzed breath volatiles from febrile Malawian children with and without uncomplicated P. falciparum malarial infection. In this work, we provide the first evidence that natural malarial infection correlates with global changes in breath volatiles that allow for accurate classification of infection status. Furthermore, we establish that volatile mosquito attractants are present at elevated levels in the breath of children with malaria.

METHODS

Breath Specimen Collection

Prior to enrollment of patients, approval for this study was obtained from both the Malawi College of Medicine Research Ethics Committee (approval no. P.05/14/1572) and the Institutional Review Board of Washington University School of Medicine (approval no. 201504128). Patients were recruited from 2 ambulatory pediatric centers in Lilongwe, Malawi. Samples were collected over a 2-week period during February 2016 from children ages 3–15 years presenting for care. Children who had positive results of both a malaria rapid diagnostic test (RDT) and blood smear were classified as having malaria (n = 17), while those with negative results of both a RDT and blood smear were enrolled as uninfected controls (n = 18). After informed consent was obtained from caretakers, vital signs were recorded, anthropometric data were collected, and a brief demographic and health history form was completed. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed further in the Supplementary Materials. Parasitemia was quantified at a later date, using fixed and stained thin smears. For each sample, 1000 red blood cells were counted and inspected for malaria parasites by an experienced parasitologist blinded to the patient’s clinical status.

Breath specimen collection was performed as previously reported with alterations detailed here [20]. In brief, ≥ 1 L of exhaled breath was collected in a 3-L SamplePro Flexfilm sample bag (SKC). By using a set flow pump (ACTI-VOC, Markes International), exactly 1 L of breath was pumped through an inert stainless-steel sorbent tube packed with Tenax 60/80, Carbograph 1 60/80, and Carboxen 1003 40/60 (Camsco). These are absorbent resins that capture VOCs present in the breath for transportation and later analysis. Sorbent tubes were stored at −20°C prior to shipment on freezer packs for off-site mass spectrometric analysis.

Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) Analysis of Samples

Samples were analyzed by GC/MS 1 month after initial collection. All samples were evaluated with a TurboMatrix 650 ATD (Perkin Elmer) connected to a Leco Pegasus 4D GCxGC-TOFMS system. A gaseous standard mixture was added to each tube immediately prior to analysis. Raw data files along with patient infection status are available at the Metabolomics Workbench repository, where they have been assigned the project identifier PR000612 [26].

For analysis of the overall VOC profile, files were deconvoluted using MassHunter Qualitative Analysis (Agilent). Deconvoluted compound lists were imported into Mass Profiler Professional (Agilent) for alignment. Peaks were normalized to the 1,2-dichlorobenzene-D4 internal standard (m/z 150 at 11.7 minutes). Compounds unique to individual samples were filtered out from further analysis, as were siloxane contaminants.

The compounds α-pinene, 3-carene, isoprene, and acetone and the 1,2-dichlorobenzene-D4 internal standard were specifically identified and quantified in the GC/MS data files, using OpenChrom [27]. The abundances of these compounds in each sample were calculated by integrating the respective base ion peaks. Peak areas were normalized to the base ion peak area of 1,2-dichlorobenzene-D4. For each specific compound, peaks with a normalized area of ≤0.0002 were considered at or below the limit of detection.

Classifier

Using the aligned, standardized compound list generated by Mass Profiler Professional, VOCs that were present in at least 20 participants at a raw signal of >20000 counts were used in classifier analysis. Class labels were assigned to each subject on the basis of their infection status, and VOCs were sorted on the basis of their correlation with infection status. The abundances of the 6 most correlated VOCs were summed to create a cumulative abundance metric. Positively correlated VOC abundances (that is, abundances of compounds that were higher in malaria-positive patients) were added, while negatively correlated VOC abundances (ie, those with lower abundances in malaria-positive patients) were subtracted. A nearest mean classification algorithm (binary classification) with a leave-1-breath-sample-out cross-validation scheme was followed to assign predicted infection status. The predicted label (malaria [+] or malaria [−]) was compared to the actual status to quantify the performance, as shown in Figure 1. The classification performance, as a function of the number of VOCs included, was used to determine the optimal number of VOCs needed for identification (Supplementary Figure 1D).

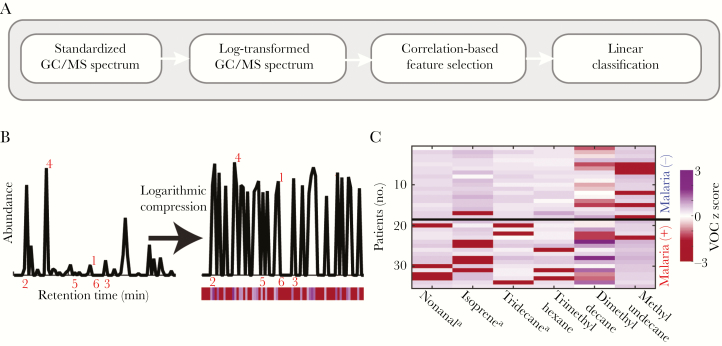

Figure 1.

Presence of malarial infection corresponds with an altered breath VOC profile. A, Schematic of the analytical approach followed to classify breath samples. B, Representative total ion chromatograph determined by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/MS). After removal of contaminants and normalization, a log2 operator was used to compress the abundance values obtained from each subject. For visualization, the abundance of each volatile organic compound (VOC) is represented as a color bar shown below the GC/MS chromatograph. Red numbers indicate the 6 VOCs with the largest absolute correlations. C, z score abundances for the 6 VOCs with the highest absolute correlation with malarial infection status are shown. Compound structures and properties are specified in Supplementary Table 1. −, negative; +, positive. aCompound identity confirmed by comparison to pure standard.

RESULTS

We performed a descriptive prospective case-control study of ambulatory pediatric patients in Lilongwe, Malawi. Cases were defined as having malaria on the basis of both rapid diagnostic testing and microscopic analysis of thick blood smears. Demographic and clinical characteristics in the malaria-positive versus malaria-negative patient populations are shown in Table 1 (n = 35). Across all these characteristics, infected and uninfected cohorts were broadly similar, specifically in regards to potential confounding factors such as fever. Diet, which can have an impact on breath volatiles, was fairly homogenous and was not markedly different between the 2 groups (Supplementary Figure 2). For infected patients, the average parasitemia level was 2.2% of erythrocytes (range, <0.001%–6% of erythrocytes).

Table 1.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Variable | Malaria Positive (n = 17) |

Malaria Negative (n = 18) |

P a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age, y | 8 (6–10) | 7 (5–8.5) | .33 |

| Female sex | 8 (47) | 10/17 (59) | .73 |

| Reported symptoms | |||

| Fever | 16 (94) | 15 (83) | .60 |

| Diarrhea | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | .49 |

| Vomiting | 5 (29) | 4 (22) | .71 |

| Headache | 16 (94) | 14 (78) | .34 |

| Abdominal pain | 13 (76) | 17 (94) | .18 |

| Muscle/joint pain | 12 (71) | 4 (22) | .007 |

| Other characteristics b | |||

| Chronic malnutrition | 5/16 (31) | 3 (17) | .43 |

| Acute malnutrition | 0/16 (0) | 1 (6) | 1 |

| Uses bed net | 9 (53) | 10 (56) | 1 |

| Malaria within past 3 mo | 3 (18) | 5/17 (29) | .69 |

Data are median value (interquartile range) or no. (%) of patients. If ≥1 patient was excluded due to gaps in the record, the number given is the fraction of the total.

aBy the Fisher exact test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate.

bChronic and acute malnutrition are defined as height-for-age and body mass index-for-age z scores of ≥2 SDs below the median, respectively.

Breath volatiles were captured onto sorbent material and subsequently released by thermal desorption for analysis by GC/MS. For quality-control analysis of breath specimen collection, the levels of the 2 most common and abundant breath VOCs, isoprene and acetone, were compared to levels in room-air control specimens [28]. For each patient, we found that the abundance of isoprene and/or acetone was at least twice the level observed in room air control specimens, confirming successful breath specimen collection (Supplementary Figure 3).

Using an unbiased correlation-based approach, we identified candidate biomarkers that best differentiated between breath samples from malaria-positive individuals and those from malaria-negative individuals (Figure 1A). Following preprocessing (Figure 1B), GC/MS data were used to correlate the abundance profile of each VOC with malarial infection status. This strategy identified VOCs that were positively or negatively correlated with infection status, indicating that P. falciparum infection leads to a distinct breathprint marked by both increases and decreases in levels of specific breath compounds (Figure 1C). While no individual compound served as an adequate classifier in isolation, the cumulative abundance across the 6 VOCs with the highest absolute correlation values proved to be a robust strategy to classify infection status (Figure 2A). All 6 malaria-associated VOCs—methyl undecane, dimethyl decane, trimethyl hexane, nonanal, isoprene, and tridecane—have been previously reported as present in human breath [14]. Isoprene is known to have an endogenous origin, while the other 5 VOCs are believed to be derived through oxidative stress–induced lipid peroxidation [28, 29]. The 3 branched alkanes (methyl undecane, dimethyl decane, and trimethyl hexane) were annotated through manually curated reference to a spectral library. The other 3 VOCs (nonanal, isoprene, and tridecane) were definitively identified by comparison to pure commercial standards. Characteristic data for all 6 compounds are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

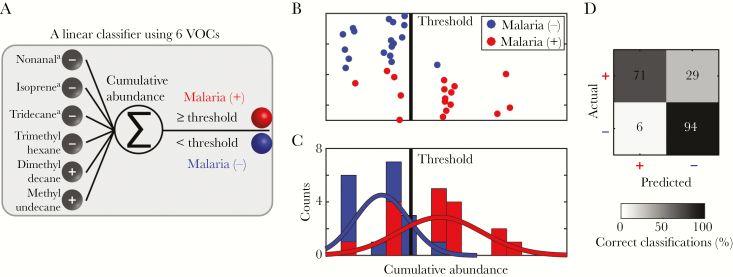

Figure 2.

Accurate classification of falciparum malarial infection status achieved with 6 volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from breath specimens. A, Schematic of the classification approach. The internal standard normalized abundance values of the 6 VOCs are linearly combined to create a cumulative abundance metric. Negatively correlated VOCs are subtracted rather than added. B, Cumulative abundance of the 6 VOCs across all subjects shows clear separation between the 2 populations. C, Distribution of cumulative abundance of biomarkers from children with (red) or without (blue) falciparum malaria. D, Confusion matrix of actual and predicted malarial infection status. Displayed are the percentages of patients in each class. A total of 83% of classifications were correct, with a specificity of 94% and sensitivity of 71%. aCompound identify confirmed by comparison to pure standard.

Together, the 6 candidate biomarkers yield a cumulative abundance metric, which provides a more Gaussian distribution than individual component features (Figure 2C). Critically, with an appropriate cumulative abundance threshold, we classified malarial infection status with 83% accuracy (Figure 2B–D and Supplementary Figure 1). Potential confounding clinical characteristics (including sex, age, and malnutrition) were not found to be associated with significant differences in cumulative abundance of these 6 biomarkers (Supplementary Table 2). Thus, we have identified 6 specific breath compounds that represent candidate biomarkers, whose targeted detection may be used for noninvasive diagnosis of malaria.

We expect that other combinations of breath compounds may also have diagnostic utility. As illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1B–D, the changes in breath volatiles that we observed as a result of malarial infection are not limited to the top 6 compounds. Including additional compounds (up to the top 30 highest-correlated compounds) does not result in lower accuracy, and, in validation studies, alternative highly correlative compounds may have improved reproducibility. The full list of compounds used for unbiased discovery, and their correlation values, can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

From this extended list, 2 compounds in particular, the monoterpenes α-pinene and 3-carene, drew special attention. Previous in vitro studies identified that cultured P. falciparum–infected red blood cells produce a number of plant-like terpenes, including the monoterpene α-pinene [30, 31]. Plant-produced terpenes in general influence Anopheles species mosquito attraction and feeding behavior [31]; these mosquitoes feed on plant-derived nectar in addition to the blood meals taken by females.

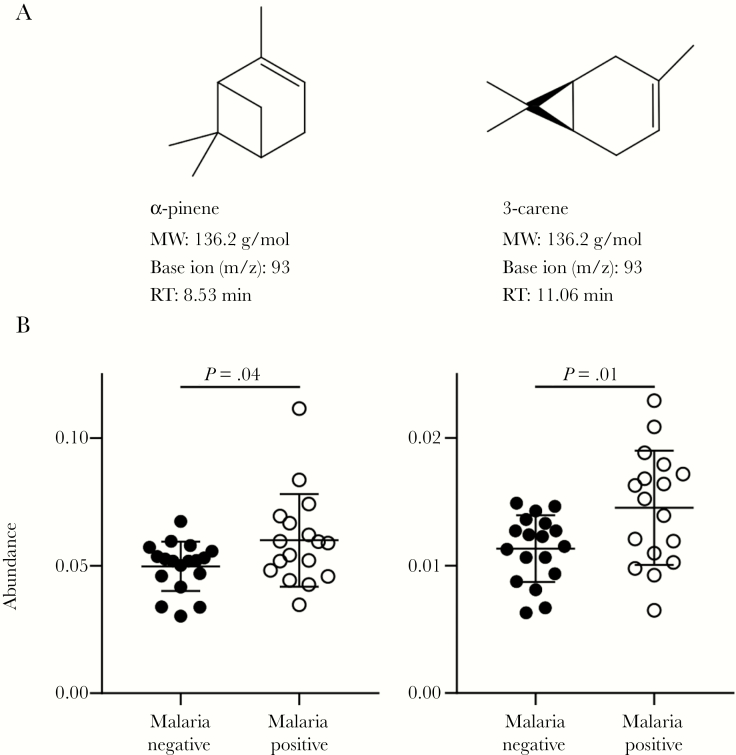

Using base ion peak areas, we found that the mean abundances of α-pinene (P = .04, with 20% higher mean) and 3-carene (P = .01, with a 28% higher mean) were both significantly higher in breath specimens from children with malaria as compared to uninfected children (Figure 3). To confirm that the changes in α-pinene and 3-carene abundances did not reflect a general trend toward increased capture of monoterpenes during malarial infection, we evaluated levels of the structurally similar terpene (+)-limonene. We found that the (+)-limonene abundance was not increased in breath specimens from children with malaria (Supplementary Figure 4). Additionally, potential confounding clinical characteristics (including sex, age, and malnutrition) were not found to be associated with significant differences in α-pinene and 3-carene abundances (Supplementary Table 2). Using a receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, we found that breath levels of either α-pinene or 3-carene categorized malarial infection status with a maximum accuracy of 69% and 77%, respectively (Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Malarial infection correlates with elevated levels of volatile mosquito-attractant terpenes. A, Structure and features of the volatile terpenes α-pinene and 3-carene. MW, molecular weight; RT, retention time. B, Breath levels of α-pinene (left) and 3-carene (right) in 18 children without and 17 with falciparum malaria. Abundance was quantified by peak area of base ion normalized to internal standard. Mean values and standard deviations are shown. The Student t test was used to assess for significant difference between mean values.

DISCUSSION

Despite impressive gains over the last 2 decades, only half of children with fever in Africa receive diagnostic testing for malaria as per World Health Organization recommendations [1]. Given the costs of traditional microscopy of blood smears and the caveats of the intrinsic frequency of false-positive results and rising frequency of false-negative results of HRP2-based RDTs, the case is clear for innovative alternatives. In this work, we provide the first report of candidate diagnostic biomarkers and elevated levels of mosquito attractants in the breath of P. falciparum–infected children from a typical malaria-endemic clinical setting.

This study demonstrates the promise of breath testing for malaria diagnosis. We found robust and global differences in breath VOC composition based on infection status (Supplementary Figure 1B), with as few as 6 breath volatiles used to provide a classification accuracy of 83% (Figure 2). The patterns of breath volatiles identified in this population of Malawian children with uncomplicated falciparum malaria will require extensive validation in heterogeneous locations and populations. However, these initial studies provide a solid framework upon which to build a future diagnostic test. Targeted testing for specific volatiles may be feasible. Alternatively, so-called electronic nose (eNose) technology may have features more suitable to rapid, field-stable, point-of-care testing in malaria-endemic settings. eNoses implement sensor arrays and pattern-recognition technology to describe the chemical composition of complex volatile mixtures, such as breath [32]. One such existing commercial device, Aeonose, was used in a recent clinical study of pulmonary tuberculosis, achieving a diagnostic sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 92% [33]. Although technological barriers persist for clinical implementation [32], less extensive adaptation may be required to implement eNoses in settings and scenarios in which noninvasive testing would be highly valuable, such as border-crossing sites and population-based screening efforts in elimination settings, a not insignificant need [2].

In the breath of children with malaria, we found increased levels of 2 terpenes, a class of biomolecules often used by plants for insect communication. Elevated quantities of specific breath terpenes (Figure 3) represent a biologically plausible chemical mechanism for the finding that malarial infection increases Anopheles species host attraction [22–24]. In particular, we propose that the monoterpene α-pinene represents a strong candidate to be considered as a malaria-induced volatile mosquito signal. In culture, increased α-pinene levels have been observed reproducibly upon P. falciparum infection of host cells [30, 31]. In addition, this terpene is a direct, potent, and specific activator of Anopheles gambiae odorant receptors (AgOR21 and AgOR50), confirming that the primary mosquito vector expresses the biochemical machinery to detect this molecule [30]. Finally, several lines of evidence suggest that α-pinene specifically modulates mosquito-feeding behavior. Both α-pinene and the related 3-carene are among the volatiles produced by mosquito-preferred nectar-providing plant species [34, 35]. In addition, a blend of volatiles containing α-pinene enhanced Anopheles mosquito blood feeding to the same degree as Plasmodium infection [31]. Because malaria-induced volatiles are chemically identical to those produced by mosquito-preferred plants, our findings indicate that malaria parasites may hijack mosquito behavior to increase transmission. Future studies are required to evaluate whether similar strategies may be used by additional vector-borne microbial pathogens. However, mosquito attraction is highly complex, and the contribution of these elevated monoterpene levels to the overall increased preference for malarial parasite–infected hosts will require dedicated mosquito behavior testing.

Our work also highlights the potential utility of α-pinene and other terpenes as components of superior odor-baited mosquito traps. Successful mass trapping campaigns depend on human-scent-mimicking odor baits [36], with some initial promise seen from lures composed of plant attractants, including α-pinene [37, 38]. New odor baits blending human- and plant-derived attractant compounds may prove powerful tools for boosting the efficacy of malaria control efforts.

There are several potential limitations to our findings. Our study patients were largely homogeneous with respect to ethnicity, diet, and geographical location. Additional independent validation of our candidate biomarkers in both pediatric and adult patients in a variety of settings is necessary. Our results are also distinct from the previous breath metabolite findings reported by Berna et al from naive healthy adults with experimentally induced, submicroscopic, P. falciparum infection [20], which identified increased levels of 4 small thioethers as the best classifier of infection status. In our study, these specific thioethers were only observed in the breath of a single patient, who tested negative for malaria. Thus, the thioethers may prove to be markers of the earliest stages of infection, but levels may subside by the time an individual presents for care. The longer time between sample collection and analysis, as well as different sorbent material, may also explain an absence of thioethers in this study. Similarly, the lack of detection by Berna et al of the 6 biomarkers and elevated terpenes reported here may be the result of the marked difference in parasite burden or age between the 2 study populations. The experimentally infected adults achieved a maximum parasitemia level of <2.5 × 10–6% of erythrocytes, using a conversion factor of 4 million red blood cells/μL, nearly one hundred thousand times less than the average parasitemia level in our study. In addition, our study participants are likely to have had multiple previous episodes of malaria. Prior parasite exposure may be required for host-generated volatiles produced during P. falciparum infection. Finally, children with uncomplicated falciparum malaria virtually always carry gametocytes, the sexual stage of the parasite required for mosquito transmission [39–42]. Because gametocytes take >1 week to mature, they are not present during experimental infections, and therefore examination of patients with experimental malaria will miss gametocyte-specific changes in volatiles. The increased mosquito attraction observed during malarial infection appears to require the presence of circulating gametocytes [22–24]; this was most recently highlighted in the largest experimental cohort to date [21]. Future studies will evaluate the correlation between our candidate biomarkers and parasite burden, prior parasite exposure, and gametocyte carriage.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Presented in part: 2017 Annual Meeting of the American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

Author contributions. C. L. S., N. K., A. O. J., and B. R. designed the experiments. L. B. B., I. T., M. M., and R. M. collected the samples. C. L. S. and N. K. performed the experiments and analysis. C. L. S., N. K., L. B. B., A. O. J., B. R., and I. T. wrote the main manuscript text. C. L. S. and N. K. prepared the figures and tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments. We thank Michelle Eckerle, Dana Hodge, Peter Kazembe, Robert Krysiak, Hans-Joerg Lang, Wentai Lou, Mark Manary, Jonathan Ngoma, Karl Seydel, Terrie Taylor, and the NIH/NIGMS Biomedical Mass Spectrometry Resource at Washington University.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01AI103280 and R21AI123808-01 to A. O. J.), the Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children’s Hospital (to A. O. J., I. T., and B. R.), the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (to A. O. J.), and the Washington University Monsanto Excellence Fund (to C. L. S.).

Potential conflicts of interest. A. O. J., C. L. S., I. T., B. R., and N. K. are coinventors of intellectual property associated with this research (US provisional patent application 62/550283). A. O. J. currently serves on the scientific advisory board of Pluton Biosciences.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). World malaria report 2016. Geneva: WHO, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bell D, Fleurent AE, Hegg MC, Boomgard JD, McConnico CC. Development of new malaria diagnostics: matching performance and need. Malar J 2016; 15:406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bell D, Wongsrichanalai C, Barnwell JW. Ensuring quality and access for malaria diagnosis: how can it be achieved?Nat Rev Microbiol 2006; 4:S7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wongsrichanalai C, Barcus MJ, Muth S, Sutamihardja A, Wernsdorfer WH. A review of malaria diagnostic tools: microscopy and rapid diagnostic test (RDT). Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 77:119–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Falade CO, Ajayi IO, Nsungwa-Sabiiti J et al. Malaria rapid diagnostic tests and malaria microscopy for guiding malaria treatment of uncomplicated fevers in Nigeria and prereferral cases in 3 African Countries. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:290–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wilson ML. Malaria rapid diagnostic tests. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:1637–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kumar N, Pande V, Bhatt RM et al. Genetic deletion of HRP2 and HRP3 in Indian Plasmodium falciparum population and false negative malaria rapid diagnostic test. Acta Trop 2013; 125:119–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gamboa D, Ho MF, Bendezu J et al. A large proportion of P. falciparum isolates in the Amazon region of Peru lack pfhrp2 and pfhrp3: implications for malaria rapid diagnostic tests. PLoS One 2010; 5:e8091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berhane A, Russom M, Bahta I, Hagos F, Ghirmai M, Uqubay S. Rapid diagnostic tests failing to detect Plasmodium falciparum infections in Eritrea: an investigation of reported false negative RDT results. Malar J 2017; 16:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koita OA, Doumbo OK, Ouattara A et al. False-negative rapid diagnostic tests for malaria and deletion of the histidine-rich repeat region of the hrp2 gene. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012; 86:194–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cheng Q, Gatton ML, Barnwell J et al. Plasmodium falciparum parasites lacking histidine-rich protein 2 and 3: a review and recommendations for accurate reporting. Malar J 2014; 13:283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Watson OJ, Slater HC, Verity R et al. Modelling the drivers of the spread of Plasmodium falciparum hrp2 gene deletions in sub-Saharan Africa. Elife 2017; 6:e25008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization (WHO). False-negative RDT results and implications of new reports of P. falciparum histidine-rich protein 2/3 gene deletions. Global Malaria Programme Information Note. WHO reference no. WHO/hTM/GMP/2017.18. Geneva: WHO, 2017.

- 14. de Lacy Costello B, Amann A, Al-Kateb H et al. A review of the volatiles from the healthy human body. J Breath Res 2014; 8:14001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nakhleh MK, Amal H, Jeries R et al. Diagnosis and classification of 17 diseases from 1404 subjects via pattern analysis of exhaled molecules. ACS Nano 2017; 11:112–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koo S, Thomas HR, Daniels SD et al. A breath fungal secondary metabolite signature to diagnose invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1733–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peng G, Tisch U, Adams O et al. Diagnosing lung cancer in exhaled breath using gold nanoparticles. Nat Nanotechnol 2009; 4:669–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kahn N, Lavie O, Paz M, Segev Y, Haick H. Dynamic reath. Nano Lett 2015; 15:7023–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boots AW, Bos LD, van der Schee MP, van Schooten FJ, Sterk PJ. Exhaled molecular fingerprinting in diagnosis and monitoring: validating volatile promises. Trends Mol Med 2015; 21:633–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berna AZ, McCarthy JS, Wang RX et al. Analysis of breath specimens for biomarkers of Plasmodium falciparum infection. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:1120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Busula AO, Bousema T, Mweresa CK et al. Gametocytemia and attractiveness of Plasmodium falciparum-infected Kenyan children to Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. J Infect Dis 2017; 216:291–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lacroix R, Mukabana WR, Gouagna LC, Koella JC. Malaria infection increases attractiveness of humans to mosquitoes. PLoS Biol 2005; 3:e298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Batista EPA, Costa EFM, Silva AA. Anopheles darlingi (Diptera: Culicidae) displays increased attractiveness to infected individuals with Plasmodium vivax gametocytes. Parasit Vectors 2014; 7:251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. De Moraes CM, Stanczyk NM, Betz HS et al. Malaria-induced changes in host odors enhance mosquito attraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:11079–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cornet S, Nicot A, Rivero A, Gandon S. Malaria infection increases bird attractiveness to uninfected mosquitoes. Ecol Lett 2013; 16:323–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sud M, Fahy E, Cotter D et al. Metabolomics Workbench: An international repository for metabolomics data and metadata, metabolite standards, protocols, tutorials and training, and analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 2016; 44:D463–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wenig P, Odermatt J. OpenChrom: a cross-platform open source software for the mass spectrometric analysis of chromatographic data. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mochalski P, King J, Klieber M et al. Blood and breath levels of selected volatile organic compounds in healthy volunteers. Analyst 2013; 138:2134–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hakim M, Broza YY, Barash O et al. Volatile organic compounds of lung cancer and possible biochemical pathways. Chem Rev 2012; 112:5949–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kelly M, Su CY, Schaber C et al. Malaria parasites produce volatile mosquito attractants. MBio 2015; 6:e00235–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Emami SN, Lindberg BG, Hua S et al. A key malaria metabolite modulates vector blood seeking, feeding, and susceptibility to infection. Science 2017; 355:1076–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fitzgerald JE, Bui ETH, Simon NM, Fenniri H. Artificial Nose Technology: Status and Prospects in Diagnostics. Trends Biotechnol 2017; 35:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coronel Teixeira R, Rodríguez M, Jiménez de Romero N et al. The potential of a portable, point-of-care electronic nose to diagnose tuberculosis. J Infect 2017:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nyasembe VO, Teal PE, Mukabana WR, Tumlinson JH, Torto B. Behavioural response of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae to host plant volatiles and synthetic blends. Parasit Vectors 2012; 5:234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nikbakhtzadeh MR, Terbot JW 2nd, Otienoburu PE, Foster WA. Olfactory basis of floral preference of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) among common African plants. J Vector Ecol 2014; 39:372–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Homan T, Hiscox A, Mweresa CK et al. The effect of mass mosquito trapping on malaria transmission and disease burden (SolarMal): a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2016; 6736:207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yu BT, Ding YM, Mo JC. Behavioural response of female Culex pipiens pallens to common host plant volatiles and synthetic blends. Parasit Vectors 2015; 8:598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nyasembe VO, Tchouassi DP, Kirwa HK et al. Development and assessment of plant-based synthetic odor baits for surveillance and control of malaria vectors. PLoS One 2014; 9:e89818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eziefula AC, Bousema T, Yeung S et al. Single dose primaquine for clearance of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes in children with uncomplicated malaria in Uganda: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, dose-ranging trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Von Seidlein L, Drakeley C, Greenwood B, Walraven G, Targett G. Risk factors for gametocyte carriage in Gambian children. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2001; 65:523–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Price R, Nosten F, Simpson JA et al. Risk factors for gametocyte carriage in uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999; 60:1019–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vandendool H, Kratz PD. A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas-liquid partition chromatography. J Chromatogr 1963; 11:463–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.