Abstract

With recent ovarian cancer screening studies showing no clinically significant mortality benefit, preventing this disease, identifying high-risk populations, and extending survival remain priorities. However, several challenges are impeding progress in ovarian cancer research. With most studies capturing exposure information from 10 or more years ago, evaluation of how changing patterns of exposures, such as new oral contraceptive formulations and increased intrauterine device use, might influence ovarian cancer risk and survival is difficult. Risk factors for ovarian cancer should be evaluated in the context of tumor histotypes, which have unique molecular features and cells of origin; this is a task that requires large collaborative studies to achieve meaningful sample sizes. Importantly, identification of novel modifiable risk factors, in addition to those currently known to reduce risk (eg, childbearing, tubal ligation, oral contraceptive use), is needed; this is not feasibly implemented at a population level. In this Commentary, we describe important gaps in knowledge and propose new approaches to advance epidemiologic research to improve ovarian cancer prevention and survival, including updated classification of tumors, collection of data on changing and novel exposures, longer follow-up on existing studies, evaluation of diverse populations, development of better risk prediction models, and collaborating prospectively with consortia to develop protocols for new studies that will allow seamless integration for future pooled analyses.

Globally, ovarian cancer is the seventh most common malignancy in women, with more than 238 000 cases diagnosed and 151 000 deaths in 2012 (1). Ovarian cancer is clinically symptomatic only at late stages when survival is poor, and early detection is elusive; two large trials of population-level screening with transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125 levels failed to show a clinically significant mortality benefit, though change in CA-125 over time shows some promise in the UK Screening Study, with cases being diagnosed at a slightly earlier stage (2–4). The US Preventive Services Task Force is in the process of updating screening recommendations for ovarian cancer and will provide an in-depth review of this issue (5). Risk models have yet to achieve the predictive accuracy needed to identify high-risk women in the general population (without a strong family history) for targeted screening or to intervene with prophylactic surgery (6–8). Over the last several decades, ovarian cancer survival rates have remained largely unchanged and personalized treatment with novel therapeutic approaches lags behind that of most other cancers. In 2016, the Institute of Medicine released a report on the “State of the Science in Ovarian Cancer Research” (9) describing key strategies for research and funding into prevention, early detection, diagnosis, and treatment. The report, and a subsequent special issue on ovarian cancer in Cancer Causes and Control (10), highlighted the need for more research to better understand how specific exposures, both established and new, influence ovarian cancer development and survival. Here, we describe important gaps in knowledge and propose new approaches to advance epidemiologic research to improve ovarian cancer prevention and survival.

Ovarian Cancer Histotypes Are Distinct Diseases: Implications for Epidemiologic Studies

Contrary to a belief held for nearly 40 years, the ovarian surface epithelium is likely not the origin for the majority of ovarian cancers (11,12). Instead, fallopian tube cells may be precursors for most high-grade serous cancers (13,14), and endometrial or endometriosis cells likely are precursors for clear cell and endometrioid tumors (15–18). Based on dramatic differences in molecular features observed across tumor histotypes, epithelial ovarian cancer is likely comprised of several biologically distinct diseases with varying etiologies (13,19,20). Analyses of lifestyle and genetic factors have elucidated histotype-specific associations and have revealed associations that were not consistently observed when all ovarian cancers were combined (eg, cigarette smoking with mucinous tumors, and endometriosis with endometrioid and clear cell tumors) (15,21,22). Importantly, substantial refinement of the criteria for classifying ovarian tumors has occurred over the past decade, largely related to reclassifying high-grade endometrioid, transitional, and undifferentiated tumors as high-grade serous, such that the 2014 World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria yielded considerably more concordance between pathologists. Furthermore, differences in prognosis using these criteria have been observed, implying that contemporary diagnostic criteria better reflect the underlying biology of the different histotypes (23). Taken together, these results demonstrate the importance of integrating accurately classified patient-level tumor information with epidemiologic data to understand the etiology of each ovarian cancer histotype. Within this context, a priority for future prevention research will be to identify factors associated with the development of precursor lesions for the different histotypes.

Most existing case-control studies of ovarian cancer enrolled women diagnosed in 2010 or earlier (8,24), and they may suffer from histological misclassification. Reducing misclassification should result in increased power to detect differences in risk and survival by histotype, and thus consortium-based efforts are focusing on improving the accuracy and reproducibility of ovarian tumor type assignment. To reduce misclassification of high-grade endometrioid, many of which are likely high-grade serous and late-stage mucinous, most of which are likely metastatic to the ovary, the combination of histology, stage, and grade information works reasonably well (25) and does not require access to tumor tissue or histology slides. For new studies and the subset of existing studies that have available tumor tissue, standardized pathology review using the 2014 WHO criteria is recommended, along with immunohistochemical staining. An additional challenge for epidemiologic studies of ovarian cancer is the discovery that high-grade serous tumors likely encompass several molecular subtypes, as evidenced by differences in gene expression patterns (26,27); these may also be associated with distinct etiologies, risk factors, and differences in survival, but larger studies are needed to clarify if differences exist (28). For example, to achieve 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.5 for an exposure with 10% prevalence (eg, tubal ligation), one would need 1000 cases and 1000 controls for each type. These are not trivial case numbers considering that there are three to five high-grade serous molecular subtypes and four other histotypes. The use of immunohistochemical staining, somatic mutations, mRNA expression, methylation patterns, or other biomarkers to further clarify the etiologic heterogeneity of ovarian cancer is now possible, but many existing studies do not have tumor tissue available. For investigations of high-grade serous molecular subtypes, access to mRNA from tumor tissue will be required until surrogate measures for these subtypes are developed for application to large-scale epidemiology studies, as has been suggested recently using morphologic features (29,30). To reach sample sizes necessary to identify histotype- and subtype-specific etiologic factors, data from older studies must be augmented with data from new epidemiologic studies for accurate tumor histotyping and with tissue collection, as needed, for molecular subtyping (31).

Changing Patterns in Exposures Over Time: How Do These Factors Influence Ovarian Cancer Risk?

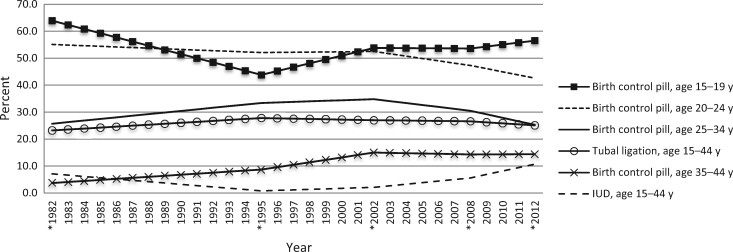

Most risk and protective factors for ovarian cancer were identified in data collected decades ago. Changes in these factors (particularly evolving reproductive and contraceptive patterns) could influence ovarian cancer incidence over time. Indeed, in the United States and other high-income countries, ovarian cancer incidence decreased slightly over the last decades (32). This is likely due in part to increased oral contraceptive pill (OCP) use from the early 1960s (33). OCP use is one of the most effective ways to reduce risk of ovarian cancer and endometrial cancer among a large proportion of the at-risk population, although use slightly increases risk of breast and cervical cancers among current users, but with an estimated overall net survival benefit (34–37). However, there have been substantial changes over time in OCP formulations (lower doses of estrogen and the addition of newer progestins), patterns of administration (continuously vs monthly cycles), and usage by different age groups (Figure 1). Specifically, OCP use is declining in women age 20 to 34 years but continues to increase in younger women as the preferred method of contraception (38). The implications of these changes on future ovarian cancer incidence are unknown but are of high priority for prevention research. Recent data from studies of more recent cohorts of women are not sufficient to establish whether newer formulations and changing patterns of OCP use continue to reduce risk of ovarian cancer as in the past (39–44). More data and longer follow-up are needed to fully understand how new OCPs influence risk.

Figure 1.

Changing pattern of contraceptive use by age group may predict changes in future risk of ovarian cancer. Values represent percent of contracepting women. In 2011 to 2013, this includes the oral contraceptive pill only. In previous surveys, this includes the oral contraceptive pill and emergency contraception/morning-after pill. Asterisks represent known values; unknown values of intervening years were estimated using linear interpolation (89). IUD = intrauterine device.

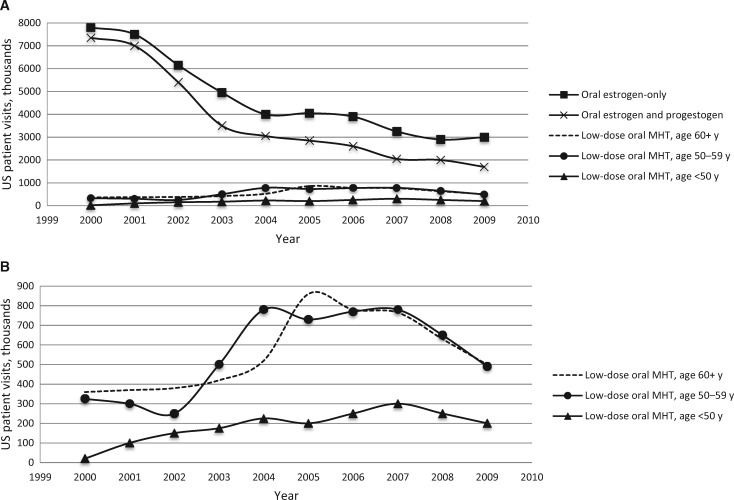

The early 2000s saw the introduction of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices (LNG-IUD) that deliver hormones directly to the gynecological tract, reducing systemic hormonal exposure. Use of IUDs, which are more effective contraceptives than OCPs, is advocated by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (45) and others (46), and it is increasing (Figure 1). While early studies suggest that breast cancer risk may be elevated among LNG-IUD users, how this compares with OCP use and whether these IUDs reduce risk of ovarian cancer are unclear (47–49). Further, menopausal hormone therapy use has decreased substantially over the last 15 years after the results from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial were announced in 2002 to 2004 (Figure 2A). Importantly, most epidemiological studies reflect patterns of use from the pre-WHI era. US cancer registry data suggest a decline in ovarian cancer incidence following the WHI reports, but few epidemiological studies currently cover this time period (32). As patterns of contraception and menopausal hormone use change with respect to dose and application (Figure 2B) (50), it is important to study their effects on future risk of ovarian cancer and other health outcomes.

Figure 2.

Changing pattern of use of low-dose menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) by age group in the aftermath of the Women’s Health Initiative trial. Data are reported as number of US office–based physician visits by women age 18 years and older in which MHT use was reported by formulation, dose, and women’s age between January 2001 and December 2009 from the National Disease and Therapeutic Index, which provides nationally representative estimates of practices of non–federally employed US office–based physicians via a physician survey. A) Trends in MHT use by formulation and age group. B) Expanded view of trends in low-dose MHT by age group. Reproduced with permission from the publisher Wolters Kluwer (50). MHT = menopausal hormone therapy.

Other previously understudied exposures are emerging as potentially relevant to the risk of developing ovarian cancer. For example, recent studies suggest that pelvic inflammatory disease may slightly increase risk of serous ovarian cancer (51–53) and genital powder use may increase risk of all ovarian cancer histotypes (54), while high prediagnostic CRP levels have also been associated with increased risk (55–61), lending support to the hypothesis that inflammation contributes to ovarian carcinogenesis (62). There is also some evidence that stress may increase risk of certain types of ovarian cancer (63,64). While intriguing, these novel associations remain only suggestive until they are examined and confirmed in additional populations. Increasing overweight and obesity is an epidemic in developed countries, yet higher body mass index (BMI) appears to be only modestly associated with increased risk for ovarian cancer in women of European ancestry, and risk may be mostly restricted to nonserous histotypes (65). Furthermore, the impact of obesity has been underexplored with respect to metabolites from adipose tissue (eg, cytokines and hormones), modifying associations with established risk factors for ovarian cancer. There are important differences in exposure prevalence of established risk factors by race/ethnicity such as obesity, hysterectomy, body powder use, and smoking (66,67), and the strength of individual risk factor associations may differ by race/ethnicity. For example, BMI appears to be more strongly associated with ovarian cancer risk among black women (68), but few studies of ovarian cancer have been conducted in nonwhite populations. A major limitation of most current studies, and hence of consortia comprising those studies, is the lack of racial/ethnic diversity in the study populations.

The association between common medications and ovarian cancer risk has not been well studied because most existing epidemiological studies have very limited information on medication use. Some evidence suggests that aspirin reduces ovarian cancer risk (69), and it has been hypothesized that other medications such as metformin, statins, and antihypertensives may influence cancer risk, but data for ovarian cancer are sparse (69–75). Linkage of prescription databases to ovarian cancer incidence and mortality data, such as research currently being performed in Scandinavia (71,76,77), will provide an invaluable new avenue to assess the potential risks and benefits associated with medication use. While these studies have provided insights into possible associations, large-scale data sets that link medication use, epidemiologic factors, and accurate histotyping are needed to fully understand these relationships.

Current Risk Prediction/Stratification of Ovarian Cancer Is Limited, and Better Risk Markers Are Needed

An important translational goal of epidemiologic ovarian cancer research is to identify women with an absolute risk of ovarian cancer that is high enough to warrant additional diagnostic procedures or prophylactic surgery. Because ovarian cancer is rare in the general population, risk factors or biomarkers must have very large effects to meaningfully change absolute risk of ovarian cancer (78). A risk prediction model integrating the four most important factors (parity, oral contraceptive use, duration of menopausal hormone therapy, and family history of breast or ovarian cancer) associated with ovarian cancer risk showed only limited discriminatory ability (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.59) (7). The successful identification of many risk loci in genome-wide genetic association studies has prompted efforts to develop risk prediction models combining polygenic risk scores and epidemiologic risk factors. A recent risk prediction model incorporated 17 established epidemiological risk factors and 17 genome-wide statistically significant single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) using data from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium, but the addition of the SNP data led to only a slight increase in discriminatory ability (from an AUC of 0.65 to 0.66) (8). It is likely that there are many more genetic risk loci for ovarian cancer, but much larger sample sizes are needed to discover these, particularly loci associated with individual histotypes (79). Gains in predictive accuracy could also come from the discovery of novel risk factors for ovarian cancer, development of histology-specific models, or alternate risk stratification approaches, as recently described for breast cancer and coronary artery disease (80,81). Currently, only a small proportion of the general population would be predicted as having a clinically relevant high absolute risk, and this group would only include a minority of those who ultimately develop ovarian cancer (82). Interaction with physicians and patient advocates is important to evaluate clinically relevant risk thresholds for prevention, surveillance, or early detection and how they would be applied.

Identification of Potentially Modifiable Lifestyle Factors That Influence Survival Is Needed

Currently, very few studies exist with data on lifestyle factors as well as detailed clinical, treatment, and follow-up information to identify modifiable factors that could improve survival (83–85). While it can be efficient to build survivor cohorts from existing epidemiological studies, these retrospective cohorts often lack detailed information on treatment and clinical follow-up. Importantly, few studies have collected the postdiagnostic exposure information necessary to identify factors that could be changed after diagnosis in order to impact survival. For instance, a recent study of women who stopped smoking when they were diagnosed with breast cancer indicated that the subjects had lower mortality from breast cancer and respiratory cancer than women who continued to smoke (86), and it has been suggested that patients with ovarian cancer may likewise benefit from smoking cessation interventions (87). Similar studies that collect information on modifiable exposures after ovarian cancer diagnosis are needed (84).

Opportunities and Limitations of Existing Consortia to Identify Novel Factors Associated With Risk and/or Survival

The importance of consortia to evaluate epidemiologic hypotheses cannot be overstated. While individual studies have clearly shown strong inverse associations with increasing parity and OCP use, it has only been possible to advance understanding of risk factor profiles for the different histotypes by pooling data (15,21,22,65,88). However, existing consortia are limited to the data available in individual studies and harmonization of heterogeneous data, often precluding the ability to evaluate detailed aspects of use (eg, duration, frequency) and new exposures, such as modern contraceptive methods or different patterns of use. While ongoing cohorts may often collect new data, the timeline needed to amass incident ovarian cancer cases is long and the breadth of exposure to information is often limited. Conversely, nearly all existing case-control studies were conducted before 2010, often did not ask about important novel risk factors, and lacked ethnic and racial diversity. Depending on the type of exposure and the risk marker, adding standardized exposure assessments and measuring new biomarkers in ongoing cohort studies can yield important information. For other questions, it is more efficient to establish new case-control studies with high response proportions for both cases and controls that can accrue large numbers of patients in a short period of time to address questions more rapidly than is possible in cohort studies.

Summary

Although ovarian cancer incidence has declined slightly over the past few years, secular changes in risk and protective factors, particularly contraceptive and reproductive patterns, may reverse this trend. The limitations of existing studies to provide new information about the future population’s risk of ovarian cancer vis-à-vis underlying trends such as increasing obesity are evident. Critical to mitigating risk and mortality from ovarian cancer is continued surveillance through new studies, with emphasis on accurate histotyping, ethnically diverse populations, assessment of novel and changing exposures pre- and postdiagnosis, and detailed clinical and follow-up data.

Table 1.

Changing ovarian cancer risk factors and secular trends in high-income countries with predominantly white populations

| Exposure | Change in exposure | Possible effect on population |

|---|---|---|

| Parity | Increase in nulliparous women, fewer births | Parity reduction will lead to increased population risk across most histotypes |

| Oral contraceptive use | Change in dose, formulation, use pattern | Protective effects may be reduced, affecting most histotypes |

| Intrauterine device | Increased use | Not known |

| Obesity | Strong increase | Positive association with endometrioid histotype, increased population risk of this histotype; interactions with hormonal risk factors may increase risk of other histotypes |

| Smoking | Reduction of intensity and duration of smoking | Positive association with mucinous histotype, inverse association with clear cell cancer, population effect unclear |

| Tubal ligation | Reduction | Inverse association with all histotypes, strongest for endometrioid and clear cell; fewer tubal ligations may increase population risk |

| Menopausal hormone therapy | Strong decrease in menopausal hormone use in the early 2000s, possible increase in low-dose and transdermal modalities since then | Not known |

References

- 1. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed April 2, 2017.

- 2. Buys SS, Partridge E, Black A, et al. Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2011;30522:2295–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jacobs IJ, Menon U, Ryan A, et al. Ovarian cancer screening and mortality in the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;38710022:945–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wentzensen N. Large ovarian cancer screening trial shows modest mortality reduction, but does not justify population-based ovarian cancer screening. Evid Based Med. 2016;214:159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walsh T, Casadei S, Lee MK, et al. Mutations in 12 genes for inherited ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinoma identified by massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;10844:18032–18037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li K, Husing A, Fortner RT, et al. An epidemiologic risk prediction model for ovarian cancer in Europe: The EPIC study. Br J Cancer. 2015;1127:1257–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pfeiffer RM, Park Y, Kreimer AR, et al. Risk prediction for breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancer in white women aged 50 y or older: Derivation and validation from population-based cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2013;107:e1001492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clyde MA, Palmieri Weber R, Iversen ES, et al. Risk prediction for epithelial ovarian cancer in 11 United States-based case-control studies: Incorporation of epidemiologic risk factors and 17 confirmed genetic loci. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;1848:579–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Committee on the State of the Science in Ovarian Cancer Research, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine, et al. Ovarian Cancers: Evolving Paradigms in Research and Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tworoger SS, Doherty JA.. Epidemiologic paradigms for progress in ovarian cancer research. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;285:361–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dubeau L. The cell of origin of ovarian epithelial tumors and the ovarian surface epithelium dogma: Does the emperor have no clothes? Gynecol Oncol. 1999;723:437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karst AM, Drapkin R.. Ovarian cancer pathogenesis: A model in evolution. J Oncol. 2010:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Crum CP, Drapkin R, Miron A, et al. The distal fallopian tube: A new model for pelvic serous carcinogenesis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;191:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Piek JM, van Diest PJ, Zweemer RP, et al. Dysplastic changes in prophylactically removed fallopian tubes of women predisposed to developing ovarian cancer. J Pathol. 2001;1954:451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pearce CL, Templeman C, Rossing MA, et al. Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: A pooled analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012;134:385–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wiegand KC, Shah SP, Al-Agha OM, et al. ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;36316:1532–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jones S, Wang TL, Shih Ie M, et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Science. 2010;3306001:228–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kurman RJ, McConnell TG.. Characterization and comparison of precursors of ovarian and endometrial carcinoma: Parts I and II. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18(3 suppl):181S–189S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Boyd N, et al. Ovarian carcinoma subtypes are different diseases: Implications for biomarker studies. PLoS Med. 2008;512:e232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gilks CB, Ionescu DN, Kalloger SE, et al. Tumor cell type can be reproducibly diagnosed and is of independent prognostic significance in patients with maximally debulked ovarian carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2008;398:1239–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wentzensen N, Poole EM, Trabert B, et al. Ovarian cancer risk factors by histologic subtype: An analysis from the Ovarian Cancer Cohort Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2016;3424:2888–2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Faber MT, Kjaer SK, Dehlendorff C, et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of ovarian cancer: A pooled analysis of 21 case-control studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;245:989–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kommoss S, Gilks CB, du Bois A, et al. Ovarian carcinoma diagnosis: The clinical impact of 15 years of change. Br J Cancer. 2016;1158:993–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. OCAC. http://ocac.ccge.medschl.cam.ac.uk/. http://ocac.ccge.medschl.cam.ac.uk/.

- 25. Kelemen LE, Goodman MT, McGuire V, et al. Genetic variation in TYMS in the one-carbon transfer pathway is associated with ovarian carcinoma types in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;197:1822–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tothill RW, Tinker AV, George J, et al. Novel molecular subtypes of serous and endometrioid ovarian cancer linked to clinical outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;1416:5198–5208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;4747353:609–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schildkraut JM, Iversen ES, Akushevich L, et al. Molecular signatures of epithelial ovarian cancer: Analysis of associations with tumor characteristics and epidemiologic risk factors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;2210:1709–1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Murakami R, Matsumura N, Mandai M, et al. Establishment of a novel histopathological classification of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma correlated with prognostically distinct gene expression subtypes. Am J Pathol. 2016;1865:1103–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang C, Armasu SM, Kalli KR, et al. Pooled clustering of high-grade serous ovarian cancer gene expression leads to novel consensus subtypes associated with survival and surgical outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2017; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Doherty A, Cole Peres L, Wang C, et al. Challenges and opportunities in studying the epidemiology of ovarian cancer subtypes. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2017; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang HP, Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, et al. Ovarian cancer incidence trends in relation to changing patterns of menopausal hormone therapy use in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;3117:2146–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Callahan RL, Kopf GS, Strauss JF 3rd, et al. Tubal contraception and ovarian cancer risk: A global view. Contraception. 2016;953:223–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE, et al. Oral contraceptive use and breast cancer: A prospective study of young women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;1910:2496–2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lipnick RJ, Buring JE, Hennekens CH, et al. Oral contraceptives and breast cancer. A prospective cohort study. JAMA. 1986;2551:58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Luhn P, Walker J, Schiffman M, et al. The role of co-factors in the progression from human papillomavirus infection to cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;1282:265–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roura E, Travier N, Waterboer T, et al. Correction: The influence of hormonal factors on the risk of developing cervical cancer and pre-cancer: Results from the EPIC cohort. PLoS One. 2016;113:e0151427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sundstrom B, Ferrara M, DeMaria AL, et al. Integrating pregnancy ambivalence and effectiveness in contraceptive choice. Health Commun. 2017;327:820–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Koushik A, Grundy A, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Hormonal and reproductive factors and the risk of ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;285:393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bethea TN, Palmer JR, Adams-Campbell LL, et al. A prospective study of reproductive factors and exogenous hormone use in relation to ovarian cancer risk among black women. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;285:385–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Webb PM, Green AC, Jordan SJ.. Trends in hormone use and ovarian cancer incidence in US white and Australian women: Implications for the future. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;285:365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kumle M, Weiderpass E, Braaten T, et al. Risk for invasive and borderline epithelial ovarian neoplasias following use of hormonal contraceptives: The Norwegian-Swedish Women's Lifestyle and Health Cohort Study. Br J Cancer. 2004;907:1386–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moorman PG, Alberg AJ, Bandera EV, et al. Reproductive factors and ovarian cancer risk in African-American women. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;269:654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shafrir A, Schock H, Poole EM, et al. A prospective cohort study of oral contraceptive sue and ovarian cancer among women in the United States born from 1947-1964. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;285:371–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Women’s Health Care Physicians. June 20, 2011. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/News-Releases/2011/IUDs-Implants-Are-Most-Effective-Reversible-Contraceptives-Available.

- 46. Payne JB, Sundstrom B, DeMaria AL.. A qualitative study of young women's beliefs about intrauterine devices: Fear of infertility. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;614:482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Heikkinen S, Koskenvuo M, Malila N, et al. Use of exogenous hormones and the risk of breast cancer: Results from self-reported survey data with validity assessment. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;272:249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lyytinen HK, Dyba T, Ylikorkala O, et al. A case-control study on hormone therapy as a risk factor for breast cancer in Finland: Intrauterine system carries a risk as well. Int J Cancer. 2010;1262:483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Soini T, Hurskainen R, Grenman S, et al. Cancer risk in women using the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in Finland. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(2 pt 1):292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tsai S, Stefanick M, Stafford RS.. Trends in meopausal hormone therapy use of US office-based physicians 2000-2009. Menopause. 2011;184:385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhou Z, Zeng F, Yuan J, et al. Pelvic inflammatory disease and the risk of ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;285:415–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rasmussen CB, Jensen A, Albieri V, et al. Is pelvic inflammatory disease a risk factor for ovarian cancer? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;261:104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rasmussen CB, Kjaer SK, Albieri V, et al. Pelvic inflammatory disease and the risk of ovarian cancer and borderline ovarian tumors: A pooled analysis of 13 case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;1851:8–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Terry KL, Karageorgi S, Shvetsov YB, et al. Genital powder use and risk of ovarian cancer: A pooled analysis of 8,525 cases and 9,859 controls. Cancer Prev Res. 2013;68:811–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lundin E, Dossus L, Clendenen T, et al. C-reactive protein and ovarian cancer: A prospective study nested in three cohorts (Sweden, USA, Italy). Cancer Causes Control. 2009;207:1151–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. McSorley MA, Alberg AJ, Allen DS, et al. C-reactive protein concentrations and subsequent ovarian cancer risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;1094:933–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ose J, Schock H, Tjonneland A, et al. Inflammatory markers and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer by tumor subtypes: The EPIC cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;246:951–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Poole EM, Lee IM, Ridker PM, et al. A prospective study of circulating C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor 2 levels and risk of ovarian cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;1788:1256–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Toriola AT, Grankvist K, Agborsangaya CB, et al. Changes in pre-diagnostic serum C-reactive protein concentrations and ovarian cancer risk: A longitudinal study. Ann Oncol. 2011;228:1916–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Trabert B, Pinto L, Hartge P, et al. Pre-diagnostic serum levels of inflammation markers and risk of ovarian cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian cancer (PLCO) screening trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;1352:297–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zeng F, Wei H, Yeoh E, et al. Inflammatory markers of CRP, IL6, TNFalpha, and soluble TNFR2 and the risk of ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;258:1231–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ness RB, Cottreau C.. Possible role of ovarian epithelial inflammation in ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;9117:1459–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Poole EM, Kubzansky LD, Sood AK, et al. A prospective study of phobic anxiety, risk of ovarian cancer, and survival among patients. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;275:661–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Huang T, Tworoger SS, Hecht JL, et al. Association of ovarian tumor beta2-adrenergic receptor status with ovarian cancer risk factors and survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;2512:1587–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Olsen CM, Nagle CM, Whiteman DC, et al. Obesity and risk of ovarian cancer subtypes: Evidence from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. Endocrine Related Cancer. 2013;202:251–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Schildkraut JM, Abbott SE, Alberg AJ, et al. Association between Body Powder Use and Ovarian Cancer: The African American Cancer Epidemiology Study (AACES). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2016;2510:1411–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kelemen LE, Abbott S, Qin B, et al. Cigarette smoking and the association with serous ovarian cancer in African American women: African American Cancer Epidemiology Study (AACES). Cancer Causes Control. 2017; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bandera EV, Qin B, Moorman PG, et al. Obesity, weight gain, and ovarian cancer risk in African American women. Int J Cancer. 2016;1393:593–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Trabert B, Ness RB, Lo-Ciganic WH, et al. Aspirin, nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, and acetaminophen use and risk of invasive epithelial ovarian cancer: A pooled analysis in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;1062:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Armaiz-Pena GN, Allen JK, Cruz A, et al. Src activation by beta-adrenoreceptors is a key switch for tumour metastasis. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Baandrup L, Dehlendorff C, Friis S, et al. Statin use and risk for ovarian cancer: A Danish nationwide case-control study. Br J Cancer. 2015;1121:157–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Liu Y, Qin A, Li T, et al. Effect of statin on risk of gynecologic cancers: A meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;1333:647–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Rattan R, Giri S, Hartmann LC, et al. Metformin attenuates ovarian cancer cell growth in an AMP-kinase dispensable manner. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;151:166–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rattan R, Graham RP, Maguire JL, et al. Metformin suppresses ovarian cancer growth and metastasis with enhancement of cisplatin cytotoxicity invivo. Neoplasia. 2011;135:483–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Huang T, Poole EM, Eliassen AH, et al. Hypertension, use of antihypertensive medications, and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2016;1392:291–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Baandrup L, Friis S, Dehlendorff C, et al. Prescription use of paracetamol and risk for ovarian cancer in Denmark. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;1066:dju111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Baandrup L, Kjaer SK, Olsen JH, et al. Low-dose aspirin use and the risk of ovarian cancer in Denmark. Ann Oncol. 2015;264:787–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wentzensen N, Wacholder S.. From differences in means between cases and controls to risk stratification: A business plan for biomarker development. Cancer Discov. 2013;32:148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Phelan CM, Kuchenbaecker KB, Tyrer JP, et al. Identification of 12 new susceptibility loci for different histotypes of epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat Genet. 2017;495:680–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Maas P, Barrdahl M, Joshi AD, et al. Breast cancer risk from modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors among white women in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2016;210:1295–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Khera AV, Emdin CA, Drake I, et al. Genetic risk, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;37524:2349–2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Pearce CL, Stram DO, Ness RB, et al. Population distribution of lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;244:671–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nagle CM, Dixon SC, Jensen A, et al. Obesity and survival among women with ovarian cancer: Results from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. Br J Cancer. 2015;1135:817–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Poole EM, Konstantinopoulos PA, Terry KL.. Prognostic implications of reproductive and lifestyle factors in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;1423:574–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Praestegaard C, Jensen A, Jensen SM, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with adverse survival among women with ovarian cancer: Results from a pooled analysis of 19 studies. Int J Cancer. 2017;14011:2422–2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Passarelli MN, Newcomb PA, Hampton JM, et al. Cigarette smoking before and after breast cancer diagnosis: Mortality from breast cancer and smoking-related diseases. J Clin Oncol. 2016;3412:1315–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kelemen LE, Warren GW, Koziak JM, et al. Smoking may modify the association between neoadjuvant chemotherapy and survival from ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;1401:124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies of Ovarian Cancer. Ovarian cancer and body size: Individual participant meta-analysis including 25,157 women with ovarian cancer from 47 epidemiological studies. PLoS Med. 2012;94:e1001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattsville, MD; 2015.http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2015.htm#008. Accessed April 25, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]