Abstract

Experimental tests of community assembly mechanisms for host-associated microbiomes in nature are lacking. Asymptomatic foliar fungal endophytes are a major component of the plant microbiome and are increasingly recognized for their impacts on plant performance, including pathogen defense, hormonal manipulation, and drought tolerance. However, it remains unclear whether fungal endophytes preferentially colonize certain host ecotypes or genotypes, reflecting some degree of biotic adaptation in the symbioses, or whether colonization is simply a function of spore type and abundance within the local environment. Whether host ecotype, local environment, or some combination of both controls the pattern of microbiome formation across hosts represents a new dimension to the age-old debate of nature versus nurture. Here we used a reciprocal transplant design to explore the extent of host specificity and biotic adaptation in the plant microbiome, as evidenced by differential colonization of host genetic types by endophytes. Specifically, replicate plants from three locally-adapted ecotypes of the native grass Panicum virgatum (switchgrass) were transplanted at three geographically distinct field sites (one home and two away) in the Midwestern US. At the end of the growing season, plant leaves were harvested and the fungal microbiome characterized using culture-dependent sequencing techniques. Our results demonstrated that fungal endophyte community structure was determined by local environment (i.e., site), but not by host ecotype. Fungal richness and diversity also strongly differed by site, with lower fungal diversity at a riparian field site, whereas host ecotype had no effect. By contrast, there were significant differences in plant phenotypes across all ecotypes and sites, indicating ecotypic differentiation of host phenotype. Overall, our results indicate that environmental factors are the primary drivers of community structure in the switchgrass fungal microbiome.

Keywords: switchgrass, ecotype, community assembly, host specificity, biotic adaption, fungal endophyte, GxE

Introduction

Host-associated microbial communities are increasingly well-characterized throughout the tree of life (Christian et al. 2015), yet an understanding of the factors controlling their ecological assembly under field conditions is still lacking (Peay 2014). The microbiome is often considered as an extended phenotype of the host, yet its structure and function can be shaped both by host genetic identity and the surrounding environment. In general, it remains unclear the relative importance of host factors such as age (Hawlena et al. 2013) and immune response (Hale et al. 2014) in structuring host-associated microbiomes, versus environmental factors such as local climate (Bálint et al. 2015), soil conditions (Bakker et al. 2014), and the surrounding community of alternate host species (Bakker et al. 2014, Laforest-Lapointe et al. 2017). Furthermore, host and environmental factors can be non-independent; local environment can shape host phenotype (Johnson and Agrawal 2005), which can then feed back to shape microbiome community assembly (Gehring et al. 2014). Similarly, while local adaption to abiotic conditions is a well-studied mechanism driving genetic diversity within heterogeneous environments (Howe et al. 2003), population divergence (Agren and Schemske 2012), and patterns of population distributions across space and time (Hereford 2009), these patterns can also be driven by local adaptation to biotic conditions, such as the presence of mutualists (Warren II and Bradford 2014), antagonists (Nosil 2004) or preferred hosts for colonization (Laine et al. 2014).

For example, local adaptation of rust pathogens to ecotypes of wild flax has been demonstrated where ‘avirulence’ loci in the pathogen were strongly differentiated by host ecotype but not by distance (Laine et al. 2014). Similarly, greater virulence has been demonstrated for sympatric wheat cultivar-pathogen combinations relative to allopatric combinations (Ahmed et al. 1995). Local adaptation to host species has also been documented for vertically-transmitted symbionts, including fungal endophytes of grasses (Afkhami et al. 2014) and bacterial symbionts of parasitic nematodes (Chapuis et al. 2009). In these instances, at least one member of the partnership has restricted gene flow due to their reliance on vertical transmission during host reproduction.

However, whether local adaptation to biotic conditions is possible for asymptomatic, horizontally-transmitted microbes is less certain (Greischar and Koskella 2007). Long-distance dispersal events and horizontal gene transfer can homogenize genetic variation in microbial taxa (Hanson et al. 2012) and reduce biotic adaptation to host types (Papke and Ward 2004), or increase the likelihood of maladaptation (Sullivan and Faeth 2004). Conversely, the rapid evolution of microbial taxa, relative to their hosts, could increase genetic variation within microbial populations and strengthen biotic adaptation to local host ecotypes (Hanson et al. 2012). Biotic adaptation within host-symbiont interactions is directly analogous to the concept of host specificity, where biotic adaptation is defined as local adaptation that alters species interactions (Urban 2011) and host specificity is defined as preferential colonization of host genetic types (Barrett and Heil 2012). Both concepts depend on the relative migration rates and dispersal asymmetries between the symbiont and its host across both partners’ geographic ranges (Gandon et al. 1996, Nuismer et al. 1999). The strongest test for biotic adaptation, and host specificity, is reciprocal inoculation or exposure to local sources of inocula (Kawecki and Ebert 2004).

In plants, foliar fungal endophytes (FFE) comprise a major component of the phyllosphere (i.e., aboveground) microbiome, and increasingly are the subject of much empirical and theoretical research (Christian et al. 2015). FFE are defined by their asymptomatic infection of plant tissues during at least a portion of their life cycle, and have been isolated from every plant species studied to date (Rodriguez et al. 2009). These symbionts span diverse functional and trophic roles, such as mutualists, pathogens, and latent saprotrophs (Porras-Alfaro and Bayman 2011). Among FFE, colonization of new hosts is predominately horizontal through air-, rain-, and litter-borne spores (reviewed in Christian et al. 2015), along with occasional re-colonization of new tissues from the previous season’s buds and petioles (Kaneko and Kaneko 2004) or colonization of seeds via spores dispersed with pollen grains (Hodgson et al. 2014).

Correlational studies support local environment as an important force structuring FFE communities (Christian et al. 2016, Giauque and Hawkes 2016). Environment-specific differences in FFE community structure can arise through dispersal limitation, but few studies have explicitly examined the dispersal limits of individual FFE species. Some FFE species (or species complexes) have ranges spanning hundreds to thousands of kilometers (e.g., Lophodermium australe, Oono et al. 2014; Colletotrichum gloesporieodes, Rojas et al. 2015), while other FFE communities appear to have a more limited geographic distribution (U’Ren et al. 2012). Results from studies testing the role of host specificity as a driver of FFE community structure have also been mixed. For example, researchers have found strong variation in FFE composition across co-occurring fern species (Del Olmo-Ruiz and Arnold 2014), tree species (Vincent et al. 2016), and among tree genotypes (Ahlholm et al. 2002). By contrast, FFE composition in understory tropical grasses was independent of host species identity (Higgins et al. 2014).

Quantifying the effect of host specificity and biotic adaptation, as measured by the differential colonization of hosts, relative to the effect of local environment in structuring FFE communities, requires using host populations in both their home and away ranges. Reciprocal transplant studies can distinguish among competing mechanisms for microbial community assembly across geographically and phenotypically-defined host ecotypes. We used a reciprocal transplant study to assess whether FFE differentially colonize Panicum virgatum L. (switchgrass) ecotypes, defined here as a locally-adapted, genetically-based phenotype, or whether FFE community structure is determined primarily by the local environment and inocula sources, or whether both processes act simultaneously. We predicted that both host ecotype and the local environment would interactively affect FFE community structure, whereby certain FFE species would preferentially colonize certain host types (Bálint et al. 2015), but that local inocula sources of FFE from the surrounding environment would strongly influence FFE community structure across sites (Giauque and Hawkes 2016). However, our results support a dominant role for local environment in structuring FFE communities and more generally provide insights into the factors affecting switchgrass microbiomes that may be applicable to a wider range of plant systems.

Materials and Methods

Description of Host Study System and Sites

Switchgrass is a perennial, C4 grass native to tallgrass prairies, riparian zones, and many other habitats of North America (Casler et al. 2011) and does not form symbioses with vertically-transmitted, clavicipitaceous fungi. Its geographic distribution extends from Mexico to Canada (Casler et al. 2011). Periodic glaciation, causing alternatively high gene flow and high population isolation, has led to the large phenotypic variation observed across the plant’s range, with many described ecotypes (e.g., ‘Alamo’, ‘Kanlow’, ‘Blackwell’, ‘Pathfinder’, etc.; Casler et al. 2011, Lowry et al. 2014). This high degree of natural phenotypic variation in the grass makes it an ideal model system for the study of FFE community structure. Switchgrass is also of great interest as a biofuel source and is used widely for horticultural practices (Casler et al. 2011, Lowry et al. 2014).

Three sites were used in this study: a remnant riparian zone (“Madison”), a restored mesic prairie (“Fermi”), and an old successional field (“Shawnee”; Appendix S1: Fig. S1). Each site was chosen to represent a historic home for a given switchgrass ecotype (i.e., “Madison”, “Fermi”, and “Cave-in-Rock”, respectively). The sites were separated by at least 350 km, suggesting high genetic divergence amongst the switchgrass ecotypes. Across sites, total rainfall during the course of the experiment (i.e., 10 weeks) ranged from 11.9 cm at the old successional field to 23.3 cm at the restored mesic prairie (Midwestern Regional Climate Center cli-MATE program). A description of all three experimental sites and associated seed collection efforts is presented in the Appendix S1 Methods, as well as a table of site-level climate details (Data S1: ‘Ecotypes_WeatherData’).

Germination & Field Transplantation

Seeds from each ecotype were surface-sterilized in a 0.5% bleach solution for 5 min and then rinsed in distilled water. Seed coats were removed using sterile sand paper and the seeds were incubated on moist filter paper in sterile 6 cm petri dishes for a period of 2-5 weeks during April and May 2014. Upon germination, seedlings were transplanted into 164 mL conetainers (Stuewe and Sons, Yellow, SC10) with a 1:1 mix of pasteurized compost soil and sand. Plants were grown in the greenhouses at Indiana University for 6-10 weeks and watered as needed. Two weeks before transplantation in the field, each plant was planted into a dual-pot. To create the dual-pot, the bottom of one 3.8 L plastic pot was removed using an electric saw, then nested inside a second intact pot and filled with pasteurized compost soil. A single switchgrass plant was then transplanted into each pot and fertilized with 4.9 mL of 13-13-13 Osmocote fertilizer, after which the plants received no additional fertilizer during the course of the experiment. After moving plants to the field sites, the outer, intact pot was removed and the inner, bottomless pot sunk into the ground, flush with the soil surface. This ensured natural root growth at the field sites, while inhibiting rhizomatous spread into the surrounding plant communities. Transplantation occurred between July 9th and 12th, 2014 across the three sites.

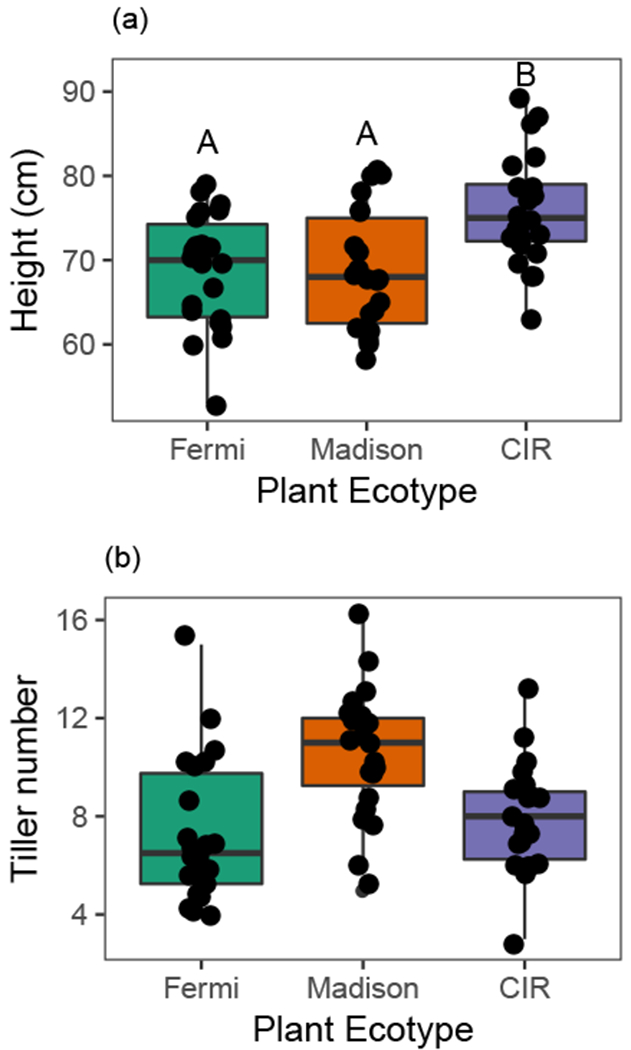

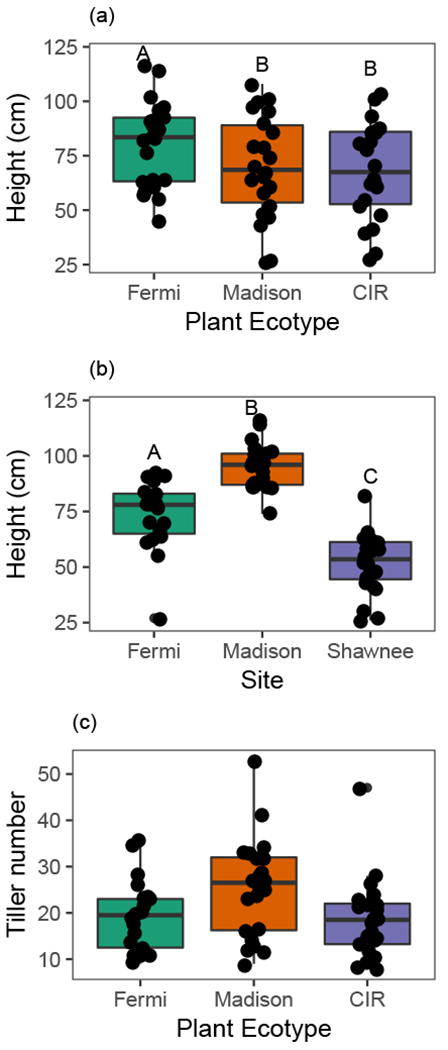

Eight plants per ecotype-site combination were used as treatment replication (8 host plants × 3 sites × 3 ecotypes). Due to low seed germination, only n=7 Cave-in-Rock were planted at the Fermi and Madison sites (N=70). Exposure to environmental sources of FFE inocula began upon transplantation into the field sites. Plant height and tiller number were recorded for all plants prior to field transplantation and microbial exposure (Fig. 1). Both pre-planting height (F2,57 = 7.95, p = 0.0009; Fig. 1A) and tiller count (Poisson model for count data; χ22,57 = 13.79, p = 0.0010; Fig. 1B) differed significantly among ecotypes, confirming genetic variation among ecotypes when grown in a common greenhouse environment. Cave-in-Rock ecotype plants were taller, while Madison ecotype plants produced more tillers.

Fig. 1. Average plant height (a) and tiller number (b) differed between ecotypes when grown in a common greenhouse environment prior to field transplantation.

Each point represents an individual plant. Vertical lines depict the data range out to 1.5 times the interquartile range. Letters depict significant pairwise differences among groups in concordance with post-hoc analyses. Cave-in-Rock is abbreviated as ‘CIR’.

Each plant was trimmed at the time of transplantation to a height of approximately 15 cm to reduce transplant shock. Before planting, each field plot was cleared of existing vegetation to a height of approximately 15 cm height and the resulting litter removed. Plots were either 2.7 m × 7.3 m or 3.7 m × 5.5 m depending on the space available at each site. Spacing between plants was 0.91 m and planting order was randomized across individuals at each field site. Local soil was used to lightly cover the base of experimental plants and pots (approx. 2 cm). Following planting, each plant was watered with 5.7 L of water after which no additional water was applied.

Sampling Method & Molecular Procedures

After 10 weeks of growth, three healthy leaves were sampled from three separate flowering tillers at mid-tiller (i.e., mid-canopy) height for each plant in September 2014 for FFE community characterization. Two Fermi ecotype plants died at the Madison site before leaves could be collected, leaving N=68 host plants. To characterize FFE communities, leaf tissues were sub-sampled. Leaves were first cut into 4-8 cm segments, which were then cut into ½ cm squares using grid paper. From these, six leaf squares were haphazardly selected and quartered into 2.5 mm square fragments, yielding 24 small leaf fragments per plant which were surface sterilized. This leaf size has been shown to be ideal for reducing fungal isolation to a single FFE per square fragment yet also capturing the greatest overall community diversity (Gamboa et al. 2002). Leaf fragments were submerged sequentially in 70% ethanol (3 min), a 0.5% bleach solution (2 min), and sterile water (1 min) using a metal tea strainer (Mejia et al. 2008). The strainer and leaf fragments were dried on a sterile Kimwipe (1 min) after which 16 leaf fragments per individual plant were haphazardly selected and plated individually on 750 uL of corn meal agar (CMA) in a sterile 2 mL microcentrifuge tube (U’Ren et al. 2009). Tetracycline was added to the CMA to prevent bacterial growth.

Tubes were then sealed with parafilm and incubated at 23°C on a 12 hr light cycle for 6 weeks. All leaf fragments which yielded fungal growth were sub-cultured onto 6cm CMA plates to produce pure cultures. CMA plates were sealed with parafilm and fungal cultures incubated for an additional 4 weeks, after which individual fungal colonies were grouped on the basis of colony morphology, color, and growth rate (Lacap et al. 2003), resulting in 44 putative morphotypes. For each defined morphotype at least one, but typically two or more isolates were subjected to DNA extraction and sequencing to confirm morphotype groupings (Shipunov et al. 2008). In addition, all cultures that had ambiguous morphological characteristics, or that appeared to be morphologically unique (i.e., singletons) were sequenced. In total, DNA was extracted, amplified, and sequenced for 381 FFE cultures. Vouchers of living mycelia were suspended in sterile water and stored at room temperature at Indiana University. Detailed molecular procedures for fungal DNA extraction and amplification are presented in the Appendix S1 Methods.

Consensus sequences for each sequenced FFE isolate were manually inspected, assembled, and edited using CodonCode (v.7.1.2, CodonCode Corporation, Centerville, MA) and grouped at the 95% sequence similarity level with a minimum of 40% overlap. Putative names were assigned to each operational taxonomic unit (OTU) using the RDP naïve Bayesian classifier (v.2.12; Wang et al. 2007) and the Warcup fungal ITS database, which includes the UNITE database (Deshpande et al. 2015). Results and confidence thresholds from this classification are presented in Data S1 (‘Ecotypes_OTU’). Representative sequences from each OTU were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers MH178669-MH178739.

Statistical Analyses

Community richness, diversity, & structure analyses –

All statistical analyses were conducted in R (v3.4.3). Species accumulation curves and estimates of total richness were inferred for fungal OTUs using the ‘specaccum’ function in the ‘vegan’ package (bootstrap estimator; Oksanen et al. 2017). A general linear model (poisson distribution) was used to test whether FFE species richness per host differed among ecotype and site treatments, and their interaction (Chi-Square test statistics). Similarly, we used a linear model to test for differences in FFE diversity (Shannon index) per host across treatments, with a Tukey’s post-hoc test to test significance of pairwise comparison between levels within treatments. We used the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index to test for differences in FFE community structure across the main effects of ecotype and site treatments, and their interaction, using a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA; ‘adonis’ function, ‘vegan’ package, 1000 permutations; Oksanen et al. 2017). A Hellinger transformation was applied to the FFE community matrix to limit the influence of abundant OTUs (Legendre and Gallagher 2001). All putative singletons were excluded from the community structure analysis (as in Higgins et al. 2014), though their inclusion did not substantially change model results. To determine how much variance was explained by host ecotype and planting site (Legendre and Gallagher 2001), we performed a variance partitioning analysis (RDA; ‘varpart’ function, ‘vegan’ package; Oksanen et al. 2017) with the transformed FFE community matrix as the response variable. Constrained RDA followed by a pseudo-F test was used to assess significance. Differences in untransformed FFE community structure were visualized using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS).

Indicator species analysis –

To determine which FFE OTUs best characterized the microbial communities as a function of switchgrass ecotype and planting site, we performed Dufrêne and Legendre’s indicator species analysis (1997) using the ‘labdsv’ package (10,000 randomizations; Roberts 2016). Indicator OTUs are identified by their relative fidelity to a specific group (i.e., ecotypes or sites) and weighted by their relative abundance across all groups.

Models of plant size –

Linear models were used to test whether plant height and tiller count at leaf sampling differed across ecotype and site treatments. For plant height, Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to test significance of pairwise comparison between groups within treatments. For tiller counts, a negative binomial model was used due to overdispersion in the data (Chi-square test statistics). For these analyses, two Madison-ecotype plants grown at the Fermi site were not included due to mislabeling at harvest (N=66 plants). Plant height and tiller number at the time of leaf sampling, as well as a metric of relative growth rate constructed from changes in plant size (i.e., the product of height and tiller number), were also tested as covariates in the models of FFE richness and diversity, but were not significant and thus are not presented.

Results

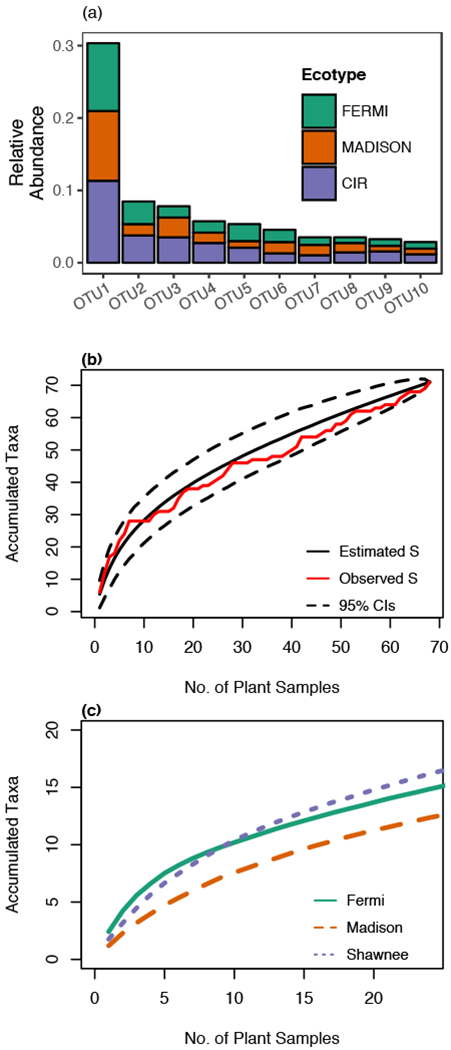

From 68 plants spanning three geographic sites and three switchgrass ecotypes, we cultured 813 isolates from 1088 leaf fragments. Of the leaf fragments plated, 70.7% yielded fungal growth. From 768 isolates, we identified 71 fungal OTUs based on sequencing data. The other 45 isolates either failed to yield high quality sequence data or were difficult to regrow from vouchers. These isolates (1 morphotype and 43 putative singletons) constituted 5.5% of the dataset and were excluded from further analyses. Of the 71 fungal OTUs identified, 38 OTUs were isolated more than once and 33 OTUs were isolated only once (i.e., singletons). Across sites, 37 OTUs were identified from plants grown at the Fermi site, 15 OTUs from the Madison site, and 47 OTUs from the Shawnee site. Similarly, for the Fermi, Madison, and Cave-in-Rock ecotypes, 43, 42, and 39 fungal OTUs were identified, respectively. The most abundant OTU represented 28.7% of all individual isolates and the top ten most abundant OTUs accounted for 71.2% of all isolates (Fig. 2A; Data S1: ‘Ecotypes_OTU’). The most abundant fungal family was the Xylariaceae, representing 21.0% of total isolates and 30 OTUs. Species accumulation curves, depicting the number of accumulated taxa per plant host, were non-asymptotic, but the estimated richness fell within the 95% confidence interval for the total experiment (Fig 2B) and showed similar rates of accumulation across sites (Fig. 2C). Thus, the dataset was considered sufficient for the community analyses described below (Del Olmo-Ruiz and Arnold 2014).

Fig. 2 – Relative abundance distribution for top ten most frequently isolated foliar fungal endophytes and species accumulation curves.

In (a), the colored bars indicate the relative colonization per OTU across the three switchgrass ecotypes. In (b), the number of observed OTUs, the bootstrap estimate of total species richness (S), and the 95 % confidence interval (CI) around the estimated richness is shown for the overall experiment. In (c), the bootstrap estimate of species richness is shown for each site. Cave-in-Rock is abbreviated as ‘CIR’.

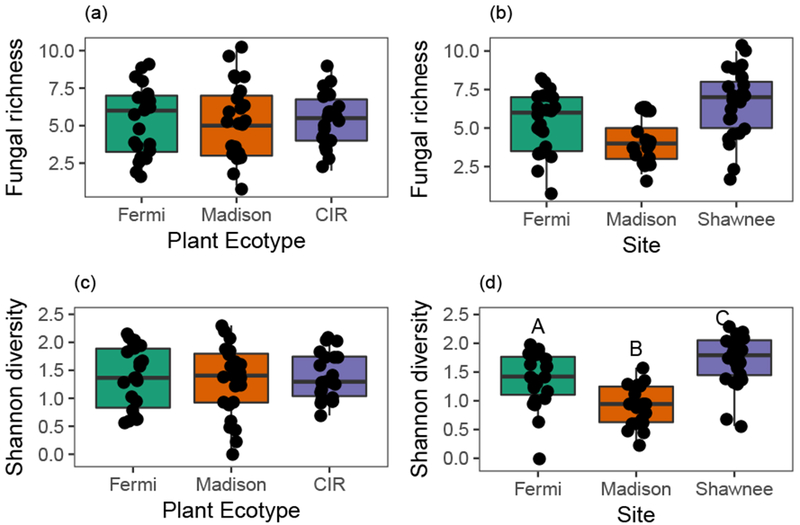

FFE richness per plant ranged from 1 to 10. Average per-plant FFE richness varied across sites (Fig. 3B, χ22,59 = 13.6, p = 0.0011), but not by ecotype (Fig. 3A, χ22,59 = 0.036, p = 0.98). In particular, average per-plant FFE richness was significantly lower at the Madison site relative to the other two sites (Fig. 3B). Average per-plant FFE diversity also varied significantly across sites (Fig. 3D, F2,59 = 18.7, p < 0.0001), but not by ecotypes (Fig. 3C, F2,59 = 0.11, p = 0.90), such that average per-plant FFE diversity was also lower at the Madison site relative to the Fermi and Shawnee sites (Fig. 3D). Overall, FFE diversity per-plant ranged from 0, for one plant where all isolates were identical, to 2.30. There was no significant interaction between ecotype and site for either FFE richness (χ22,59 = 1.5, p = 0.82) or diversity (F2,59 = 0.74, p = 0.57).

Fig. 3. FFE community richness (a,b) and Shannon diversity (c,d) varied by site, but not by ecotype.

Each point represents an individual plant. Vertical lines depict the data range out to 1.5 times the interquartile range. Letters depict significant pairwise differences among groups in concordance with post-hoc analyses. Cave-in-Rock is abbreviated as ‘CIR’.

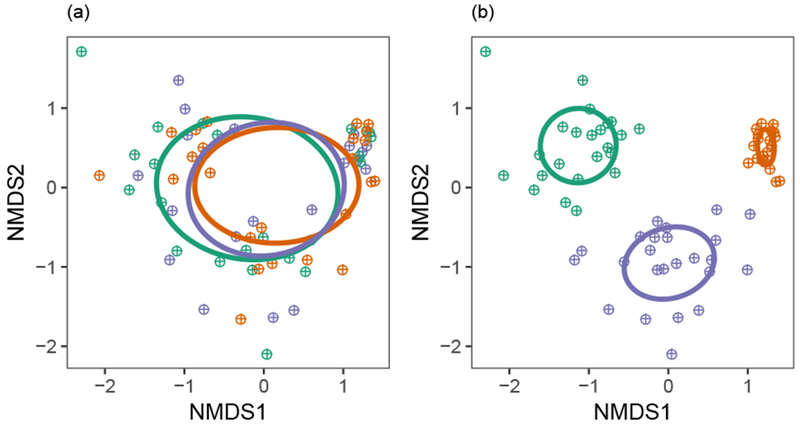

FFE community structure differed significantly by site (pseudo-F2,59 = 30.8, p = 0.0010; Fig. 4B), but not by host ecotype (pseudo-F2,59 = 0.81, p = 0.62; Fig. 4A). There was no interaction between site and host ecotype in driving FFE community structure (pseudo-F4,59 = 0.82, p = 0.71). Variance partitioning analysis showed that site explained 42.5% of the variation in FFE community structure (pseudo-F2,63 = 24.5, p = 0.001). Host ecotype did not explain any significant variation in FFE community structure (negative %; pseudo-F2,63 = 0.88, p = 0.56) leaving a large amount of unexplained variation (58.9%). Indicator species analysis identified 19 fungal OTUs that had high specificity and relative abundance to specific sites (α < 0.05, Table 1). By contrast, only two fungal OTUs (Hypoxylon spp. & Unk. Ascomycota) were indicative of specific switchgrass ecotypes (Table 1), but only when a more liberal cutoff of α < 0.10 was used.

Fig. 4. FFE community structure did not vary by ecotype (a), but did vary by site (b).

The location of each host individual in ordination space is denoted by a hatched circle. The ellipses represent the centroid and standard deviation for each treatment group (green = Fermi, orange = Madison, purple = Shawnee/Cave-in-Rock for site [a] and ecotype [b]).

Table 1 –

Dufrene Legendre Indicator species associated with each host species.

| OTU | Putative Fungal Name | Indicator Group | Indicator Value | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By Ecotype | 20 | Hypoxylon spp. | Madison | 0.1368 | 0.0935* |

| 21 | Unk. Ascomycota | Fermi | 0.1515 | 0.0645* | |

| By Site | 1 | Glomerella spp. | Madison | 0.9502 | 0.0001 |

| 2 | Alternaria spp. | Fermi | 0.8017 | 0.0001 | |

| 3 | Phaeosphaeria spp. | Fermi | 0.7999 | 0.0001 | |

| 4 | Cercospora apii | Shawnee | 0.4852 | 0.0002 | |

| 5 | Arthrinium phaeospermum | Madison | 0.7748 | 0.0001 | |

| 6 | Creosphaeria sassafras | Shawnee | 0.7083 | 0.0001 | |

| 7 | Hypoxylon perforatum | Shawnee | 0.4715 | 0.0001 | |

| 8 | Glomerella spp. | Madison | 0.4540 | 0.0001 | |

| 9 | Glomerella spp. | Fermi | 0.3913 | 0.0001 | |

| 10 | Khuskia spp. | Fermi, Shawnee | 0.2091, 0.1329 | 0.0866* | |

| 11 | Unk. Xylariaceae | Shawnee | 0.3273 | 0.0044 | |

| 12 | Lecythophora fasciculata | Madison | 0.2212 | 0.0074 | |

| 13 | Phoma spp. | Fermi | 0.3913 | 0.0001 | |

| 15 | Hypoxylon perforatum | Shawnee | 0.1983 | 0.0236 | |

| 16 | Hypoxylon investiens | Madison | 0.2078 | 0.0164 | |

| 17 | Whalleya microplaca | Shawnee | 0.2917 | 0.0014 | |

| 18 | Unk. Xylariaceae | Shawnee | 0.2917 | 0.0006 | |

| 21 | Unk. Ascomycota | Fermi | 0.2174 | 0.0049 | |

| 22 | Diaporthe spp. | Shawnee | 0.1667 | 0.0300 | |

| 23 | Annulohypoxylon truncatum | Shawnee | 0.2083 | 0.0098 | |

| 24 | Leptosphaerulina chartarum | Fermi | 0.1304 | 0.0666* | |

| 28 | Eupenicillium spp. | Fermi | 0.1304 | 0.0572* | |

Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with significant indicator values (p < 0.05) are listed in order of frequency of isolation (i.e., from common to rare). OTUs with a significance 0.05 < p < 0.10 are denoted with an asterisk. For ‘unknown’ taxonomic levels, the abbreviation ‘Unk.’ is used.

Plant height at time of FFE sampling differed among ecotypes (F2,57 = 8.67, p = 0.0005), where the Fermi ecotype was significantly taller than both the Madison and Cave-in-Rock ecotypes, which did not differ from each other (Fig. 5A). Plant height also varied by site (F2,57 = 76.8, p <0.0001), such that all two-way comparisons between sites were significant (p <0.0001 for all; Fig. 5B), but there was no interaction between ecotype and site for plant height (F4,57 = 0.60, p = 0.67). Plant tiller count at time of harvest also varied by ecotype (χ22,57 = 8.10, p = 0.0174; Fig. 5C), but not by site (χ22,57 = 2.3, p = 0.32).

Fig. 5. Average plant height differed between ecotypes (A) and field site (B), and tiller number differs between ecotypes (C) at time of leaf collection.

Each point represents an individual plant. Vertical lines depict the data range out to 1.5 times the interquartile range. Letters depict significant pairwise differences among groups in concordance with post-hoc analyses. Cave-in-Rock is abbreviated as ‘CIR’.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that site, encompassing local environmental conditions and local sources of microbial inoculum, is the primary force structuring switchgrass FFE communities. Site was a significant predictor of FFE species richness, diversity, and community structure, and explained a large portion of the variation in community structure across hosts. Contrary to our original prediction, switchgrass host ecotype had no direct effect, and did not interact with local site, in driving FFE richness, diversity, or structure. Our reciprocal transplant design provided a strong test for the role of biotic adaptation in FFE communities, but in this study we did not detect differential colonization of host ecotypes even within a single site. By contrast, both site and ecotype had significant effects on plant phenotype after 10 weeks of growth at the transplant sites, though there was no evidence of local adaptation across ecotypes (i.e., greater performance in home relative to away environments). These results indicate genetic differentiation among switchgrass ecotypes for phenotype, but not for the assembly of FFE communities.

There are several potential explanations for the strong effects of site, versus host ecotype, as the primary driver of FFE community structure in switchgrass. It is possible that the three ecotypes used in this study were too genetically similar. Genetic differences in plant phenotype were detected when ecotypes were grown in a common greenhouse environment (Fig. 1) and at the three field sites (Fig. 5), but those phenotypic differences did not result in local adaptation or correspond to differences in FFE communities (Fig. 4). Previous research has demonstrated host-genotype specific differences in FFE community structure for balsam poplar (Bálint et al. 2015) and birch trees (Ahlholm et al. 2002). Differences were also found among several cereal species and cultivars across two sites in the structure of their epiphytic and endophytic fungal colonizers (Sapkota et al. 2015). Here, the geographic distance among sites (≥350km) and the attendant environmental and biological variation may have overwhelmed differences in FFE communities due to genetic differences among ecotypes. The three sites differed in local climate, surrounding vegetation, and soil type and texture, which can have important influences on microbial community structure (Bakker et al. 2014, Giauque and Hawkes 2016). Additionally, while long-distance dispersal of spores may be possible for some fungal taxa, the effective dispersal of most fungi and other microbial groups is unknown (Hanson et al. 2012) and may have been relatively limited among the three sites, enhancing the environmental effect on community structure. Lastly, while rapid temporal turnover in FFE communities is well documented (e.g., “seasonality”, Jumpponen and Jones 2010), it may be that the 10-week period of host exposure favored local environmental effects at the expense of host-specific effects, which may require more time to become evident.

Deciphering the importance of specific mechanisms driving FFE community structure at the local site level is complex. Previous research has shown that local plant community diversity can drive differences in soil microbial communities (Bakker et al. 2014) and leaf bacterial communities (Laforest-Lapointe et al. 2017), and disturbance regimes can impact FFE community assembly (Kandalepas et al. 2015). The low FFE diversity at the Madison site might therefore be related to relatively low plant community diversity in the immediate vicinity of our experimental site (personal observation) and high level of disturbance due to water-level fluctuations along the Ohio River. Future research should test whether FFE communities are determined in part by local plant community diversity and how disturbance regimes affect the availability of FFE inoculum in the surrounding environment. Such tests could be accomplished via sampling of FFE communities in neighboring and target hosts, as well as across both disturbed and undisturbed habitats.

Increasing attention is being paid to the microbial associations of switchgrass due to its biofuel and forage crop potential (Casler et al. 2011). Previous research on plant-growth promoting microbiota in switchgrass has focused on ectomycorrhizal (i.e., Serbacina vermifera; (Ghimire and Craven 2011) and leaf-colonizing bacteria symbioses (i.e., Burkholderia phytofirmans strain PsJN; (Lowman et al. 2016, Wang et al. 2016). Fewer studies have examined FFE community differences in switchgrass (but see Ghimire et al. 2011, Giauque and Hawkes 2013). One study that examined the plant-growth promoting effects of FFE on developing switchgrass seedlings found a large range in effects of individual FFE from beneficial to antagonistic (Kleczewski et al. 2012). In our study, a large number of previously unidentified FFE species were found at all three sites, though there was no evidence for host-specific fitness effects and little evidence for host-specific colonization. Interestingly, of the 71 fungal OTUs isolated, only 34 could be identified to the species level with confidence, indicating that the identity and function of native microflora in Switchgrass hosts remains largely uncharacterized.

Given the potential importance of the switchgrass microbiome for agriculture, we conducted a comparative analysis of the fungal genera identified here with the results of Ghimire et al. (2011), Giauque & Hawkes (2013), and Kleczewski et al. (2012) (Appendix S1: Table S1). Five genera were common to switchgrass across all four studies (e.g., Alternaria, Davidiella, Gibberella, Khuskia, and Phoma) and an additional five genera were identified in three of the four studies (e.g., Cochliobolus, Epicoccum, [Eu-]Penicillium, Glomerella, Phaeosphaeria). Of these fungal genera, three were among the top ten most frequently isolated in our study (e.g., Alternaria, Khuskia, and Phaeosphaeria). This comparison among studies indicates that, despite the broad geographic range of these studies, differences in sampling methods, and use of different sequence databases for fungal classification, there are many fungal genera that appear to be widespread colonizers of switchgrass aboveground tissues.

While the interaction between genetics and environment is recognized as an important determinant of host fitness (Hereford 2009) and species interactions (Johnson and Agrawal 2005), our results strongly support local environment as the primary determinant of FFE community structure in switchgrass. FFE communities did not exhibit ecotype specificity either within sites or across sites. It remains an open question whether these results would hold for other plant groups (e.g., trees, forbs, or other grasses) or across sites that are less geographically disparate or ecologically divergent. Our results also suggest that researchers should test whether pre-inoculation with plant-growth promoting FFE in switchgrass is effective, or whether host varieties are rapidly colonized by local environmental inocula that then outcompete the inoculated FFE. Controlled tests using transplants across either spatial or abiotic gradients (e.g., precipitation patterns, prevailing wind direction, soil pH, slope, etc.), and in different biotic contexts (e.g. different neighborhood compositions) represent the next steps to determine how FFE communities are structured and how FFE communities impact plant function. Overall, our results enhance our understanding of the dominant drivers of microbiome structure in an ecologically and economically-important grass species that could be applied to a wider range of host varieties and plant study systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. R. Walton, Mr. R. Campbell, and Mr. R. McClanahan for their assistance at Fermilab and Shawnee National Forest. This work was conducted through research agreements with the U.S. DOE Fermilab National Environmental Research Park, the Fermi Research Alliance (FRA), the USDA Forest Service, and Shawnee National Forest System. We thank Z. Shearin, Q. Chai, N. Christian, K. Hoban, and M. Zaret for assistance with the project. B.K.W. was supported by the NIH Genetics, Cellular & Molecular Sciences Training Grant and as an NSF Graduate Research Fellow during the course of the experiment and through writing of the manuscript. Travel funding to field sites was provided by the Provost’s Travel Award for Women in Science at IU. The research was funded by IU’s McCormick Science Grant, as well as the G.W. Brackenridge Fellowship, Fred Seward Award, Indiana Daffodil Society Scholarship, and the Prairie Biotic Research Inc. Small Grant Award.

Footnotes

Data Availability

Data are available from Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7185185.v1

Literature Cited

- Afkhami ME, Mcintyre PJ, and Strauss SY. 2014. Mutualist-mediated effects on species’ range limits across large geographic scales. Ecology Letters 17:1265–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agren J, and Schemske DW. 2012. Reciprocal transplants demonstrate strong adaptive differentiation of the model organism Arabidopsis thaliana in its native range. New Phytologist 194:1112–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlholm JU, Helander M, Henriksson J, Metzler M, and Saikkonen K. 2002. Environmental conditions and host genotype direct genetic diversity of Venturia ditricha, a fungal endophyte of birch trees. Evolution 56:1566–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed HU, Mundt CC, and Coakley SM. 1995. Host-pathogen relationship of geographically diverse iolates of Septoria tritici and wheat cultivars. Plant Pathology 44:838–847. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker MG, Schlatter DC, Otto-Hanson L, and Kinkel LL. 2014. Diffuse symbioses: roles of plant-plant, plant-microbe and microbe-microbe interactions in structuring the soil microbiome. Molecular Ecology 23:1571–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bálint M, Bartha L, O’Hara RB, Olson MS, Otte J, Pfenninger M, Robertson AL, Tiffin P, and Schmitt I. 2015. Relocation, high-latitude warming and host genetic identity shape the foliar fungal microbiome of poplars. Molecular Ecology 24:235–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LG, and Heil M. 2012. Unifying concepts and mechanisms in the specificity of plant-enemy interactions. Trends in Plant Science 17:282–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casler MD, Tobias CM, Kaeppler SM, Buell CR, Wang Z-Y, Cao P, Schmutz J, and Ronald P. 2011. The Switchgrass genome: tools and strategies. The Plant Genome 4:273–282. [Google Scholar]

- Chapuis É, Emelianoff V, Paulmier V, Le Brun N, Pagès S, Sicard M, and Ferdy JB. 2009. Manifold aspects of specificity in a nematode-bacterium mutualism. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 22:2104–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian N, Sullivan C, Visser ND, and Clay K. 2016. Plant host and geographic location drive endophyte community composition in the face of perturbation. Microbial Ecology 72:621–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian N, Whitaker BK, and Clay K. 2015. Microbiomes: unifying animal and plant systems through the lens of community ecology theory. Frontiers in Microbiology 6:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande V, Wang Q, Greenfield P, Charleston M, Porras-Alfaro A, Kuske CR, Cole JR, Midgley DJ, and Tran-Dinh N. 2015. Fungal identification using a Bayesian classifier and the Warcup training set of internal transcribed spacer sequences. Mycologia 108:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufrene M, and Legendre P. 1997. Species assemblages and indicator species: the need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecological Monographs 67:345–366. [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa MA, Laureano S, and Bayman P. 2002. Measuring diversity of endophytic fungi in leaf fragments: does size matter? Mycopathologia 156:41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandon S, Capowiez Y, Dubois Y, Michalakis Y, and Olivieri I. 1996. Local adaptation and gene-for-gene coevolution in a metapopulation model. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 263:1003–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Gehring C, Flores-Rentería D, Sthultz CM, Leonard TM, Flores-Rentería L, V Whipple A, and Whitham TG. 2014. Plant genetics and interspecific competitive interactions determine ectomycorrhizal fungal community responses to climate change. Molecular Ecology 23:1379–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire SR, Charlton ND, Bell JD, Krishnamurthy YL, and Craven KD. 2011. Biodiversity of fungal endophyte communities inhabiting switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) growing in the native tallgrass prairie of northern Oklahoma. Fungal Diversity 47:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire SR, and Craven KD. 2011. Enhancement of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) biomass production under drought conditions by the ectomycorrhizal fungus Sebacina vermifera. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 77:7063–7067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giauque H, and V Hawkes C. 2013. Climate affects symbiotic fungal endophyte diversity and performance. American Journal of Botany 100:1435–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giauque H, and Hawkes CV. 2016. Historical and current climate drive spatial and temporal patterns in fungal endophyte diversity. Fungal Ecology 20:108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Greischar MA, and Koskella B. 2007. A synthesis of experimental work on parasite local adaptation. Ecology Letters 10:418–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale IL, Broders K, and Iriarte G. 2014. A Vavilovian approach to discovering crop-associated microbes with potential to enhance plant immunity. Frontiers in Plant Science 5:492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson CA, Fuhrman JA, Horner-Devine MC, and Martiny JBH. 2012. Beyond biogeographic patterns: processes shaping the microbial landscape. Nature Reviews Microbiology 10:497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawlena H, Rynkiewicz E, Toh E, Alfred A, Durden LA, Hastriter MW, Nelson DE, Rong R, Munro D, Dong Q, Fuqua C, and Clay K. 2013. The arthropod, but not the vertebrate host or its environment, dictates bacterial community composition of fleas and ticks. The ISME Journal 7:221–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hereford J 2009. A quantitative survey of local adaptation and fitness trade-offs. American Naturalist 173:579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins KL, Arnold AE, Coley PD, and Kursar TA. 2014. Communities of fungal endophytes in tropical forest grasses: highly diverse host- and habitat generalists characterized by strong spatial structure. Fungal Ecology 8:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson S, de Cates C, Hodgson J, Morley NJ, Sutton BC, and Gange AC. 2014. Vertical transmission of fungal endophytes is widespread in forbs. Ecology and Evolution 4:1199–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe GT, Aitken SN, Neale DB, Jermstad KD, Wheeler NC, and Chen TH. 2003. From genotype to phenotype: unraveling the complexities of cold adaptation in forest trees. Canadian Journal of Botany 81:1247–1266. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MT, and Agrawal AA. 2005. Plant genotype and environment interact to shape a diverse arthropod community on evening primrose (Oenothera biennis). Ecology 86:874–885. [Google Scholar]

- Jumpponen A, and Jones KL. 2010. Seasonally dynamic fungal communities in the Quercus macrocarpa phyllosphere differ between urban and nonurban environments. New Phytologist 186:496–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandalepas D, Blum MJ, and Van Bael SA. 2015. Shifts in symbiotic endophyte communities of a foundational salt marsh grass following oil exposure from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Plos One 10:e0122378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko R, and Kaneko S. 2004. The effect of bagging branches on levels of endophytic fungal infection in Japanese beech leaves. Forest Pathology 34:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kawecki TJ, and Ebert D. 2004. Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecology Letters 7:1225–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Kleczewski NM, Bauer JT, Bever JD, Clay K, and Reynolds HL. 2012. A survey of endophytic fungi of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) in the Midwest, and their putative roles in plant growth. Fungal Ecology 5:521–529. [Google Scholar]

- Lacap D, Hyde K, and Liew E. 2003. An evaluation of the fungal “morphotype” concept based on ribosomal DNA sequences. Fungal Diversity 12:53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Laforest-Lapointe I, Paquette A, Messier C, and Kembel SW. 2017. Leaf bacterial diversity mediates plant diversity and ecosystem function relationships. Nature 546:145–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine A-L, Burdon JJ, Nemri A, and Thrall PH. 2014. Host ecotype generates evolutionary and epidemiological divergence across a pathogen metapopulation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281:20140522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P, and Gallagher ED. 2001. Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia 129:271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowman S, Kim-Dura S, Mei C, and Nowak J. 2016. Strategies for enhancement of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L .) performance under limited nitrogen supply based on utilization of N-fixing bacterial endophytes. Plant Soil 405:47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry DB, Behrman KD, Grabowski P, Morris GP, Kiniry JR, and Juenger TE. 2014. Adaptations between ecotypes and along environmental gradients in Panicum virgatum. The American Naturalist 183:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia LC, Rojas EI, Maynard Z, Van Bael S, Arnold AE, Hebbar P, Samuels GJ, Robbins N, and Herre EA. 2008. Endophytic fungi as biocontrol agents of Theombroma cacao pathogens. Biological Control 46:4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nosil P 2004. Reproductive isolation caused by visual predation on migrants between divergent environments. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 271:1521–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuismer SL, Thompson JN, and Gomulkiewicz R. 1999. Gene flow and geographically structured coevolution. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 266:605–609. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Stevens MHH, Szoecs E, and Wagner H. 2017. “vegan” Community Ecology Package. [Google Scholar]

- Del Olmo-Ruiz M, and Arnold AE. 2014. Interannual variation and host affiliations of endophytic fungi associated with ferns at La Selva, Costa Rica. Mycologia 106:8–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oono R, Lutzoni F, Arnold AE, Kaye L, U’Ren JM, May G, and Carbone I. 2014. Genetic variation in horizontally transmitted fungal endophytes of pine needles reveals population structure in cryptic species. American Journal of Botany 101:1362–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RT, and Ward DM. 2004. The importance of physical isolation to microbial diversification. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 48:293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peay KG 2014. Back to the future: natural history and the way forward in modern fungal ecology. Fungal Ecology 12:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Porras-Alfaro A, and Bayman P. 2011. Hidden fungi, emergent properties: endophytes and microbiomes. Annual Review of Phytopathology 49:291–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DW 2016. “labdsv” Package: Ordination and Multivariate Analysis for Ecology.

- Rodriguez RJ, White JF Jr., Arnold AE, and Redman RS. 2009. Fungal endophytes: diversity and functional roles. The New Phytologist 182:314–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas EI, Rehner SA, Samuels GJ, Van Bael SA, Herre EA, Cannon P, Chen R, Pang J, Wang R, Zhang Y, Peng Y-Q, and Sha T. 2015. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides s.l. associated with Theobroma cacao and other plants in Panama: multilocus phylogenies distinguish host-associated pathogens from asymptomatic endophytes. Mycologia 102:1318–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota R, Knorr K, Jørgensen LN, O’Hanlon KA, and Nicolaisen M. 2015. Host genotype is an important determinant of the cereal phyllosphere mycobiome. New Phytologist 207:1134–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipunov A, Newcombe G, Raghavendra AKH, and Anderson CL. 2008. Hidden diversity of endophytic fungi in an invasive plant. American Journal of Botany 95:1096–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TJ, and Faeth SH. 2004. Gene flow in the endophyte Neotyphodium and implications for coevolution with Festuca arizonica. Molecular Ecology 13:649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U’Ren JM, Dalling JW, Gallery RE, Maddison DR, Davis EC, Gibson CM, and Arnold AE. 2009. Diversity and evolutionary origins of fungi associated with seeds of a neotropical pioneer tree: a case study for analysing fungal environmental samples. Mycological Research 113:432–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U’Ren JM, Lutzoni F, Miadlikowska J, Laetsch AD, and Arnold AE. 2012. Host and geographic structure of endophytic and endolichenic fungi at a continental scale. American Journal of Botany 99:898–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban MC 2011. The evolution of species interactions across natural landscapes. Ecology Letters 14:723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JB, Weiblen GD, and May G. 2016. Host associations and beta diversity of fungal endophyte communities in New Guinea rainforest trees. Molecular Ecology 25:825–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Seiler JR, and Mei C. 2016. A microbial endophyte enhanced growth of switchgrass under two drought cycles improving leaf level physiology and leaf development. Environmental and Experimental Botany 122:100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, and Cole JR. 2007. Naive bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 73:5261–5267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren II RJ, and Bradford MA. 2014. Mutualism fails when climate response differs between interacting species. Global Change Biology 20:466–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.