Abstract

A review of the brain banking literature reveals a primary focus either on the factors that influence the decision to become a future donor or on the brain tissue processing that takes place after the individual has died (i.e., the front-end or back-end processes). What has not been sufficiently detailed, however, is the complex and involved process that takes place after this decision to become a future donor is made yet before post-mortem processing occurs (i.e., the large middle-ground). This generally represents a period of many years during which the brain bank is actively engaged with donors to ensure that valuable clinical information is prospectively collected and that their donation is eventually completed. For the past 15 years, the Essential Tremor Centralized Brain Repository has been actively involved in brain banking, and our experience has provided us valuable insights that may be useful for researchers interested in establishing their own brain banking efforts. In this piece, we fill a gap in the literature by detailing the processes of enrolling participants, creating individualized brain donation plans, collecting clinical information and regularly following-up with donors to update that information, and efficiently coordinating the brain harvest when death finally arrives.

Keywords: Brain banking, Brain donation, Pre-mortem, Enrollment, Follow-up, Autopsy, Essential tremor

Introduction

Brain donation plays an integral role in studies of the pathophysiology of human neurodegenerative diseases and neuropsychiatric disorders (Kirch et al. 1991; Stopa and Bird 1989). The effectiveness of brain banks is dependent on a large multidisciplinary effort, requiring the participation of clinicians, neuropathologists, and additional research staff, all working in conjunction to ensure adequate processing and categorization of tissue to correlate morphologic findings with clinical diagnoses (Cruz-Sanchez and Tolosa 1993; Murphy and Ravina 2003; Vonsattel et al. 2008a). If properly executed, research generated from brain banks has the potential to pave the way to novel disease models and biomarkers, and thus may ultimately lay the groundwork for new therapeutic approaches and overall improved health outcomes (Beach et al. 2008; Hawkins 2010; Padoan et al. 2017; Pandey and Dwivedi 2010).

Brain banking, however, does not begin with histologic examination under a microscope, or with a Stryker saw at the autopsy table. Rather it often starts with a brief telephone call in an office space. Whether brain donors are reached out to by the brain bank coordinator, referred by a clinician, or simply led by their own intrigue and desire to contribute to medical science, their communication with brain banks will often be established many years before a final deposit to the bank is made. Indeed, long before the end of life, there must exist a working relationship between the donor and the brain bank to prospectively collect clinical data and to ensure proper plans are set up for a timely donation to take place shortly after death. Despite the importance of this pre-mortem relationship, a review of the brain banking literature reveals a distinct absence of publications that outline the process of following up and keeping track of future brain donors. Much has been written about the attitudes and perceptions surrounding brain donation (Boise et al. 2017a; Eatough et al. 2012; Garrick et al. 2003; Harris et al. 2013; Lambe et al. 2011; Schnieders et al. 2013), what influences the decision to proceed with brain donation (Boise et al. 2017b; Garrick et al. 2006; Garrick et al. 2009; Glaw et al. 2009; Jefferson et al. 2011; Schmitt et al. 2001; Stevens 1998; Sundqvist et al. 2012; West and Burr 2002), the consenting process itself (Benes 2005; Cruz-Sanchez et al. 1997; Harmon and McMahon 2014; Porteri and Borry 2008; Strous et al. 2012), brain donation as it pertains to specific diseases and controls (Adler et al. 2002; Boyes and Ward 2003; Davies et al. 1993; Glaw et al. 2009; Haroutunian and Pickett 2007; Lim et al. 1999; Schmitt et al. 2001), institutional and nationwide brain banking experiences (Azizi et al. 2006; Beach et al. 2008; de Lange et al. 2017; de Oliveira et al. 2012; Grinberg et al. 2007; Hulette 2003; Vonsattel et al. 2008a), and brain tissue processing, practices, and need for standardization (Beach et al. 2008; Cruz-Sanchez and Tolosa 1993; Dickson 2005; Graeber 2008; Palmer-Aronsten et al. 2016; Ramirez et al. 2018; Ravid and Ikemoto 2012; Vonsattel et al. 2008b), but we found no published works focusing on donor follow-up and consequent coordination of the brain procurement. Thus, much of the literature focuses on front-end processes and back-end processes, but not the large middle-ground. This is a problem as brain banks are often plagued by a lack of accompanying clinical information, diminishing the value of the collected brains. Although this clinical information may be back-filled in a retrospective manner after death, this after-the-fact approach generally results in many missing and incomplete values as well as data that are difficult to analyze because they were not collected in either a standardized or systematic manner. While yet another approach is for the brain bank to register only participants who are already enrolled in existing clinical research cohorts, thereby obviating the need to collect clinical information during life, the number of such cohorts is small and the data collected might not precisely meet the needs of the brain bank or address the specific research questions posed for the disease of interest. Hence, the prospective collection and regular up-date of clinical information during life is the optimal approach for the bank.

Though some aspects of this follow-up process may seem intuitive for researchers experienced with conducting longitudinal studies, there are challenges and intricacies specific to the brain banking process that may not be immediately apparent. The Essential Tremor Centralized Brain Repository has previously reflected about this process, briefly recounting some of our individual roles and experiences with brain banking in its multiple stages (Gillman et al. 2014), but we now seek to share specifically how we address the pre-mortem challenges innate to this type of harvest. With this in mind, this paper puts forth a brief guide on how to enroll and follow donors; it is based on our 15 years of experience with more than 170 nationwide prospective brain donations.

Brain Bank Coordinator

Before describing the work required in this “middle-ground”, it is necessary to describe the brain bank coordinator and the role they play in the process. Coordinators are responsible for overseeing the logistical aspects involved in the pre-mortem brain banking endeavor, and are usually the first point of contact that interested partizes talk to when exploring a serious interest in brain donation. As such, coordinators play a pivotal role in a brain bank’s success. Excellent organizational skills are required to keep track of all the moving pieces involved in brain banking, and an intimate understanding of study protocols is necessary to effectively serve as liaison between these components. This includes communicating with donors, their next-of-kin, other family members, pathologists, technicians, funeral homes, clinicians, and other research staff. Brain bank coordinators must also have strong interpersonal skills that allow them to build rapport with donors and their families, without which a long-lasting working relationship cannot be achieved, potentially jeopardizing the future donation. In addition to these characteristics, brain bank coordinators should ideally have a robust medical and research background that would grant them familiarity with conducting longitudinal clinical follow-up and experience with addressing end-of-life scenarios and conversations. The Essential Tremor Centralized Brain Repository has most often employed medical doctors for this purpose, although it has also employed research nurses.

Broadly speaking, the primary job of the brain bank coordinator is to ensure that donations are successfully executed. This entails creating and maintaining a respectful and compassionate working relationship with donors from the moment of initial contact all the way to their death. Throughout this relationship, coordinators must gather information from donors periodically that will aid not only in making later clinicopathological correlations and confirming diagnoses, but perhaps most crucially, will also be essential in keeping updated brain donation plans, necessary for the timely collection of the brain in the first place.

Importantly, brain donation requires the coordinator to be immediately available upon notification of the donor’s death in order to execute the preconceived plan; to accomplish this, a 24/7 pager is often a necessary component of the coordinator’s toolkit. Brain banks should ideally not rely on a single coordinator to be on call indefinitely, however. Even when the expected rate of donations is considered low and may involve a relatively lighter workload, this does not factor in the unpredictable nature of brain donation; a donor’s death is not a scheduled event, and time off cannot be planned around it. At least one back-up coordinator should be trained and familiarized with the brain donation procedure, as well as have access to the personalized plans, for occasions in which the primary brain bank coordinator is not available.

Overview

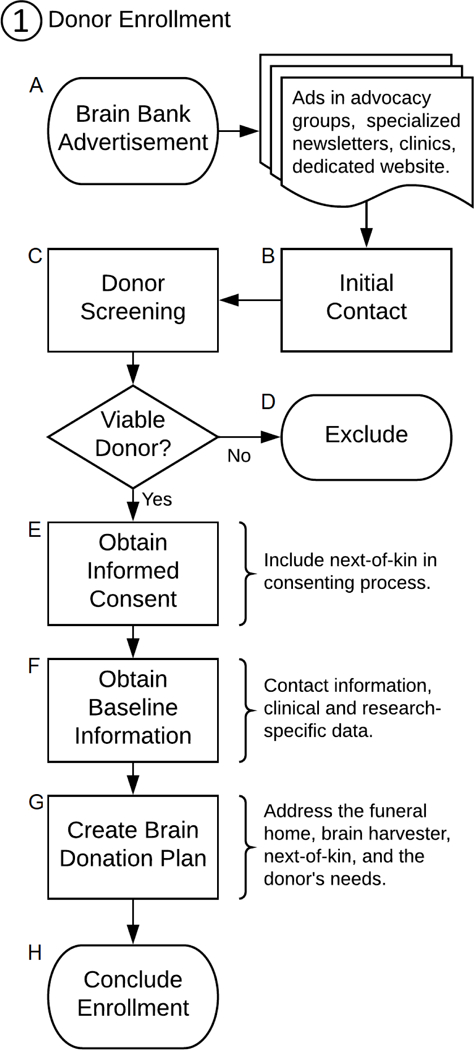

Key terms that are used in brain banking are listed in Table 1. An overview of the pre-mortem brain donation process is laid out in Figure 1, which is divided into three sub-processes (i.e., donor enrollment, donor follow-up, donor death) overseen by the brain bank coordinator. A brief summary of the main steps involved in the brain donation process is also available in Table 2. First, brain banks must come into contact with potential donors to enroll them; this involves screening interested candidates, gathering information from viable donors, and creating brain donation plans that meet donor needs (a process in and of itself detailed further on). Next, donor follow-up and communication is maintained to update clinical information—which may lead to withdrawing participants if they are deemed no longer viable—, and to ensure donation plans remain active. Lastly, when the donor dies, the brain bank coordinator must execute the brain donation plan to retrieve the tissue as soon as possible so that it can best be preserved. To facilitate comprehension, we will refer to the steps in Figure 1 using their corresponding letters placed in brackets throughout the main text (e.g. “[A],” when talking about brain bank advertising). These steps are reviewed ahead, starting with the process by which donors come across brain banks and are ultimately enrolled in them.

Table 1.

Glossary of Brain Banking Terms

| Brain Bank | A biomedical center or laboratory dedicated to the preservation and characterization of human central nervous system tissue, obtained through biopsy or post-mortem collection, for the purpose of neuroscientific research. |

| Brain Bank Coordinator | Individual within a brain bank who coordinates the logistical aspects involved in the brain donation process, and also serves as the liaison between the donors and all other components of the brain bank |

| Brain Donation Plan | Created by the coordinator before a donor’s death, the brain donation plan lays out the framework needed to ensure that brains are collected in a timely manner. Plans are dynamic documents and require periodic revision. |

| Brain Donor | Anyone who has made the decision to donate their brain after death, and who has registered with a brain bank to accomplish this. Brain donors may or may not necessarily have a neurologic disorder. Registered organ donors who wish to become brain donors must do so separately in coordination with brain banks. |

| Brain Harvester | Pathologists, autopsy technicians, dieners, coroners, or other trained professionals, who agree to perform the brain harvest at the time of a donor’s death. The harvester may perform their services at a donor’s funeral home, or may operate exclusively in their own facilities. After brain harvest by the autopsy service provider, the autopsy is performed by a licensed medical doctor. |

| Consent for Autopsy | Before autopsy can proceed, permission to perform the procedure must be provided by the legal next-of-kin in which they clearly identify themselves as such, as well as identify the donor using their full name and date of birth, the autopsy provider, the limitations of the procedure, and what the disposition of the removed tissue should be. |

| Funeral Home | Where the brain donor’s funeral services will take place. Funeral homes may or may not have an available space where the brain removal could take place, and may facilitate transportation to other sites where autopsy could proceed. |

| Next-of-Kin | In the absence of a power of attorney specifying otherwise, the next-of-kin is the donor’s closest living relative who can provide informed consent for the brain autopsy. Their order of precedence begins with the donor’s spouse, children, parents, siblings, and so forth. |

Figure 1.1.

Flowchart of the brain donation process: Donor Enrollment

Table 2.

Steps of the Brain Donation Process

| Donor Enrollment |

| Brain banks must find donors by advertising their program until a sufficient number of participants has been recruited. This also requires screening, consenting, and other documentation. |

| Creating a Personalized Brain Donation Plan |

| Incoming donors require a brain donation plan for tissue collection upon death. These plans should address the funeral home, brain harvester, and specific needs of the donor. |

| Donor Follow-up |

| Frequent contact must be established with enrolled donors to prevent attrition. Such occasions constitute an opportunity to update clinical data and review the donation plan. |

| Donor Death |

| When death takes place, the next-of-kin, funeral home, and brain harvest provider must quickly be coordinated to ensure brain donation takes place in a timely manner. |

Enrolling Participants [A – F]

Advertising.

Brain banks require brain donors and, as such, reaching out to and enrolling interested candidates is an essential part of any bank’s success. Although there is evidence that approaching potential donors face to face for recruitment is more likely to lead to brain bank registration (Barnes et al. 2012; de Lange et al. 2017; Samarasekera et al. 2013), this approach can be highly labor-intensive and may not be possible with nation-wide studies. Brain banks must therefore advertise [A] their studies widely to reach out to a larger pool of potential donors and ensure enrollment of a sufficiently-sized cohort to meet study needs. In particular, brain banks should advertise periodically through dedicated disease advocacy groups, national organizations, and in specialized newsletters tailored to the population of study to spread awareness about the brain donor program and promote recruitment. Disease advocacy groups may also play a larger role in terms of shaping the structure of and motivating the scientific aims of the banking effort.

In the current era, particularly, an online presence is expected and, as such, represents a golden opportunity for a prospective nation-wide brain donation program to come across potential donors. Besides including basic information such as the title of the study, purpose of the research, general eligibility criteria, and contact details—brain bank websites should try to preemptively address concerns that may be related to the donation process, such as religious considerations and cost of brain harvest and autopsy. Additionally, some web-hosting services can also provide valuable feedback to investigators by means of monthly reports showing how many visits the brain bank’s site receives, how users find the domain, and how much time is spent exploring the site; this information can then serve to gain a better idea of how users perceive online content and how it can be better tailored to them. Ultimately, websites may help to broaden the pool of potential donors to include highly motivated individuals who self-refer to the process and therefore require little convincing about brain donation.

Brain banks should continue advertising their programs until a sufficient number of donors has been enrolled to confidently meet study needs. Characteristics of the population of study should be accounted for when determining how many donors will be needed, and meeting study goals will likely require limiting enrollment to only those candidates above a certain age. The use of life tables can be useful for calculating how many participants will need to be enrolled to obtain x number of brains in y amount of time. For example, based on the National Vital Statistics Results from the CDC (Arias et al. 2017), about 73% of 80 year-olds can expect to survive to the age of 85. Thus, if a study were attempting to harvest 50 brains during a five-year period, a brain bank may consider enrolling 185–200 donors of average age of 80, limiting enrollment to only people above the age of 70 to avoid negatively skewing the cohort; supposing a 27% mortality, one could reasonably expect to collect 50–54 brains by the end of the study period. Estimates such as these are rough, as expected mortality rates change with each advancing year; furthermore, they should be made using mortality figures from the specific population of study, particularly if their expected mortality is significantly different than that of the general population (e.g., if the risk of mortality is greater than that of the general population).

Screening.

Once initial contact has been established [B], the next step is to properly screen interested donors [C] (Adler et al. 2002; Beach et al. 2008; Grinberg et al. 2007; Haroutunian and Pickett 2007; Lim et al. 1999; Louis et al. 2005; Vonsattel et al. 2008a). Although some candidates may be referred to brain banks by a knowledgeable health care professional, at other times potential donors with unconfirmed diagnoses contact brain banks by their own initiative. Whatever the circumstances, it is up to the brain bank to verify these diagnoses to ensure the inclusion of only those cases that would benefit the research being done, and exclude those who should not contribute to the study [D]. How diagnoses are verified and exclusion criteria ruled out may depend on funding, study protocol, or may be dictated by the nature of the disease itself. Screening methods may verify candidate viability by any combination of methods, including interviews and questionnaires (Beach et al. 2008; Grinberg et al. 2007; Haroutunian and Pickett 2007; Louis et al. 2005), or soliciting medical records from providers (Beach et al. 2008; Haroutunian and Pickett 2007), to more intensive means such as in-person diagnostic work-up (Beach et al. 2008; Haroutunian and Pickett 2007; Lim et al. 1999), requesting a videotaped neurological examination for a specialist to review (Louis et al. 2005; Louis et al. 2002), or requesting supplemental diagnostic documentation such as genetic testing (Haroutunian and Pickett 2007; Louis et al. 2005).

Consenting.

Following current Research in Human Subjects and HIPAA regulations, and just as in any prospective study, brain bank coordinators must seek informed consent [E] to enroll participants into the donation program. Numerous publications have detailed the consenting processes (Boyes and Ward 2003; Cruz-Sanchez et al. 1997; Garrick et al. 2009; Harmon and McMahon 2014; Harris et al. 2013; Hawkins 2010; Porteri and Borry 2008; Samarasekera et al. 2013; Strous et al. 2012). Generally speaking, coordinators should inform interested candidates of their rights as research participants including confidentiality, and right to withdraw, as well as basic information about the aims and structure of the study and brain donation process. Special attention should be paid to the more common concerns associated with brain donation that may otherwise be difficult to voice, such as financial costs incurred by the autopsy and how this is disbursed, potential for delayed funeral arrangements, or concerns of disfigurement precluding open casket (Samarasekera et al. 2013). Brain bank coordinators should address these concerns both openly and without being prompted, to generate an open discussion.

In order to proceed with any autopsy, it is necessary for the next-of-kin to consent to the procedure once the donor has died. However, brain bank coordinators should ideally involve the next-of-kin from the very beginning of the brain donation process when donor enrollment first commences (Azizi et al. 2006; Boyes and Ward 2003; Garrick et al. 2006; Garrick et al. 2009). Indeed, the family’s and next-of-kin’s knowledge of their loved one’s wishes for brain donation may play an important role in providing consent for autopsy (Azizi et al. 2006). A study conducted by Garrick et al. (Garrick et al. 2009) also found that the likelihood for donation was greater when the interval between seeking the next-of-kin’s consent and the donor’s death was longer. Though the majority of the intervals in this study were less than 60 hours, the reasoning behind seeking timely consent intuitively holds up for longer periods: giving families more time to consider brain donation equates to more time for them to come to terms with their loved one’s decision (Garrick et al. 2009). Not only that, but by speaking with the next-of-kin prior to the donor’s death, they themselves can become familiarized with the brain donation process; if this discussion is absent, then families may be at a loss at the time of a donor’s passing, and ultimately, they may feel too overwhelmed to address their loved one’s wish for brain donation. As such, even if the donor’s death is not expected until many years after initial enrollment, getting the next-of-kin involved in the process from the beginning may make a critical difference in ensuring a successful procurement.

Baseline information and additional documentation.

Brain banks should also request medical record release forms for donors’ treating neurologist, primary care provider, and hospital where they seek care to have a complete clinical picture of the participant (Beach et al. 2008; de Oliveira et al. 2012; Haroutunian and Pickett 2007; Palmer-Aronsten et al. 2016; Ravid and Ikemoto 2012). At the very least, medical records from the time of enrollment and from the time of death should be obtained; the first serve as a baseline snapshot [F] of the participant that help to verify study candidacy, and the latter provide the best impression of the donor’s health at the time of death. Naturally, studies will also obtain their own research-specific evaluations, but these should not serve as a substitute for actual medical records, which enhance the ability to make clinical-pathological correlations (Cruz-Sanchez and Tolosa 1993; Murphy and Ravina 2003; Vonsattel et al. 2008a).

Other useful documentation includes contact information for other persons beyond the donor and the next-of-kin. Because enrollees may be followed for multiple years before their death and brain donation occurs, having multiple contacts on file can help to avoid losing track of participants. In the years following initial enrollment, many changes can happen in a donor’s life such as changing telephone numbers or moving to a new address, and often brain banks will not immediately be informed of such changes, if at all. At worst, these events can lead to a failure in obtaining the brain from a participant to whom a lot of resources had already been dedicated. Thus, having multiple contact persons helps reduce the risk of losing follow-up on participants due to these kinds of changes.

Creating a Personalized Brain Donation Plan [G – H]

The Essential Tremor Centralized Brain Repository makes a point of creating a brain donation plan [G] as part of the enrollment process for new participants. When donations occur locally—that is, in relation to where the brain bank is physically located—, the autopsy can usually proceed in a straightforward manner, with only transportation to the brain bank needed for staff pathologists or technicians to proceed with the brain procurement after death. However, when donors are enrolled nationwide, brain bank coordinators are met with the more painstaking task of locating outside pathologists or technicians willing to do the harvest; coordinators must create detailed plans in anticipation of the future donation to ensure that tissue arrives to the repository in a timely fashion. This process may require 4 to 12 hours, often spaced throughout the course of several days, during which a back-and-forth conversation with all elements of the plan must take place. Whether a donation is expected to be local or national, however, brain bank coordinators should create plans that preemptively address the essential components of the donation process: the donor’s funeral home, the brain harvester for the case, as well as other needs that may be specific to each donor given their individual circumstances.

Funeral home.

It is common at the time of enrollment that future donors have not made any premade arrangements with a funeral home. Brain banks may seek to recruit and register participants into their programs anywhere from hours to many years before their death ultimately takes place. Even when a preference of funeral home has been expressed in the past, this choice is not necessarily set in stone and may even change at the last minute. Whatever the case, brain bank coordinators should establish communication with the donor’s funeral home as soon as possible to create a brain donor plan.

When speaking with the funeral home director, coordinators should raise the possibility early in the discussion of using the home’s embalming room (i.e., to establish whether such a room would be available in which to perform the brain harvest). Hours of operation, additional costs associated with using the embalming facilities, who will disburse these costs and in what timeframe, after-hours contact information, brain harvester information, study protocols and procedures; all of this should be talked about and documented by both the brain bank and the funeral home director for future reference. In cases where funeral homes do not lend or rent their embalming room for study purposes, transportation to a viable site will need to be discussed. In most cases, the funeral home will agree to transport the body to another establishment where the harvest could take place such as a morgue or hospital, but occasionally it may be necessary for coordinators to arrange for transportation by a third party if the funeral home declines to assume responsibility for taking the body elsewhere.

Brain harvester.

As with funeral homes, coordinators must establish the person, group, or institution who will be performing the brain harvest soon after enrollment is completed, again with the understanding that this may not be definitive. Brain harvesters can be pathologists, autopsy technicians, dieners, coroners, or other trained professionals. Whichever the case, coordinators should communicate with such providers with plenty of anticipation if possible, not only so they become familiarized with the brain bank’s harvest and autopsy protocol and needs, but also vice-versa. University hospitals, for example, often require their own consent forms to be completed by the donor and by the next-of-kin prior to accepting to do any outside autopsy; some dedicated centers may require proof of lack of prion disease or a copy of a donor’s medical records before accepting to take on a case for brain removal; other providers may exclusively work from nine to five on weekdays, or only perform harvests at funeral homes since they lack an embalming facility of their own, and others still may only perform private autopsies as a side-job during their often-limited free time.

Given how variable a brain harvester’s availability may be, delays are often inevitable. Autopsy protocols should instruct providers on how these delays should be handled, such as by indicating that the tissue be formalin-fixed instead of packed fresh if the post-mortem interval surpasses a certain number of hours. Harvester’s should also have access to the funeral home’s contact information so these delays can be communicated in a timely manner, allowing for the harvest to be rescheduled and to proceed as soon as feasibly possible.

Arranging and accounting for transportation before a donor’s death should not be overlooked when creating brain donation plans. As mentioned above, funeral homes are usually willing to assist with this, but this can be impractical if the transport costs are too high for the study’s budget. Instead, it may be more cost-efficient to identify brain harvest providers who would be able to travel long distances to the donor’s locality. Doing so will provide the added benefit of being able to keep the donor’s body in a funeral home’s cold room while waiting for the arrival of the provider, helping to preserve the tissue. Therefore, when reaching out to harvesters for brain donation plans, coordinators should ask them how far their coverage extends; while some may only tend to cases within their same metropolitan area, other services may be more accommodating and willing to travel hundreds of miles to extend their services to a certain radius around where they are based. The mileage fees generated by providers’ travels will usually be inexpensive compared to costs associated with transporting a cadaver. In fact, such travels are often necessary to reach donors in more remote areas that otherwise lack a viable harvest provider.

Another point for brain bank coordinators to discuss with brain harvesters is the shipping supplies necessary for packaging the brain. Those who only work on harvests as a part-time job, for example, may request that brain banks send them the shipping materials that meet the standards of the study protocol. Even in cases that deal with more dedicated and established autopsy services with boxing supplies readily available, coordinators may consider providing shipping materials anyway if doing so represented an opportunity to reduce the overall fee charged by the provider.

Although the task of establishing an brain harvester for any given brain donation plan can be time-consuming enough as it is, establishing back-up providers may come in handy, and indeed, may make the difference between a timely harvest and a delayed one. The fact is that despite prior agreements, unexpected events can often get in the way of a provider’s ability to work on a given case. Sometimes they may be traveling and are unavailable to work at the time of the donor’s death; they may also be handling other cases and may be unable to attend to the brain bank’s case until hours or days later, compromising the quality of the recovered tissue; other times, there is simply no response at the other end of the line when their number is dialed. Whichever the case, the benefits of having a back-up provider for every donor quickly becomes self-evident when the first choice in provider is unable to assist, and it can be well worth the extra effort if time allows it. Coordinators may choose to prioritize seeking back-ups for those donors whose death is suspected to be more imminent, or in cases where the original harvest provider is known a priori to have limited availability.

Other considerations.

Occasionally, brain donors may be interested in donating more than their brain for research purposes. Indeed, the decision to be a brain donor often stems from a broader desire to benefit science and medicine in some way (Azizi et al. 2006; Boyes and Ward 2003; Garrick et al. 2006; Kuhta et al. 2011), and as such, some donors may ask about the possibility of whole-body donation. Efforts can be made to coordinate with local whole-body donation programs through hospitals and universities to accommodate this wish. Though some programs may decline body donations without the brain, others may be open to this possibility, and it is just a matter coordinating the logistics behind this operation with all parties involved.

Circumstances applicable to only a handful of donors are not uncommon, and may need to be scrutinized by the brain bank coordinator when creating the donation plan. These different circumstances may be just a matter of some minor nuances, or they may translate to major efforts and hours needed to enable a timely donation. For example, some donors may have multiple homes such as vacation or winter homes, requiring more than one donation plan to be prepared; others may want to donate brain tissue to multiple studies, which may or may not be compatible with both studies; or prices for brain removal services may need to be negotiated to fit study budgets as no alternatives are found. Even when all the components of a donation plan are carefully set up to accommodate for foreseeable scenarios, executing plans often comes with its own set of unforeseeable situations that delay tissue collection. Despite this unfortunate reality, donation plans still play an integral role in the timely gathering of the brain bank’s subject matter. Coordinators should thus design these plans with the information that is available to them to bring the enrollment process to its conclusion [H], ensuring that no donor is enrolled without a viable plan to harvest their brain in the future.

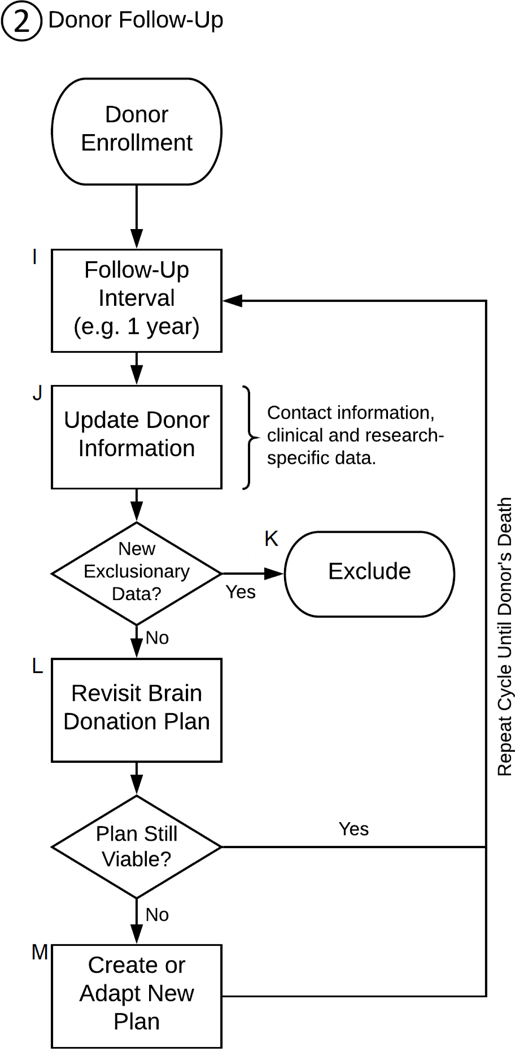

Donor Follow-Up [I – M]

Once a donor has a brain donation plan and is officially enrolled in the study, the next step is to periodically follow-up with them [I] to update their clinical data and revise their donor plans until the day of their donation finally comes. The time until death may be years, and the longer a follow-up interval is, the higher the risk of attrition becomes (Gustavson et al. 2012). Given this intrinsically indefinite nature of the follow-up period, it is easy for problems to arise during this period (see Table 3 for common problems encountered during the brain donation process). Focused efforts are needed to maintain proper retention as to avoid further biasing what is already a selective population of people willing to consent to brain donation (Barnes et al. 2012; Boise et al. 2017a; Jefferson et al. 2011; Jefferson et al. 2013; Lambe et al. 2011; Louis et al. 2005). After death, updated clinical and postmortem data are combined into the same dataset, which can be made available to interested researchers in an anonymized format.

Table 3.

Common Problems Encountered During the Brain Donation Process

| Problem | Possible Solutions | Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-mortem | ||

| Participant phone number is out of service. | Contact the family or next-of-kin for an updated number. Mail a letter to their last known address, requesting they reach out to the brain bank. |

Collect multiple contact persons information at the time of enrollment. Maintain frequent contact with participants. |

| Participant is annoyed with follow-ups. | Explain the significance of follow-ups and how they help the research being conducted. Adopt follow-up strategies to better address their concerns (e.g., less frequent follow-up, shortened evaluations). |

Build rapport with brain donors empathize with their needs be accommodating. |

| Donor has difficulty completing follow-up (e.g. due to hearing or cognitive impairment). | Ask the donor’s family or caregiver to assist with their follow-ups. Set aside more time or consider completing the patient’s evaluations in multiple parts. |

When enrolling, identify donors’ caregivers who could assist in completing follow-ups. Adapt evaluations to best fit the needs of the population of study. |

| Families are hesitant about their loved one’s decision to donate. | Talk to the families directly to explain the process to them. Address possible religious concerns, and uncertainties about who pays for the procedure. |

Encourage donors to discuss their decision openly withtheir family. Extend the coordinator’s contact information and reassure them that he/she is available to alleviate any concern they may have. |

| Post-Mortem | ||

| Planned brain harvester is unavailable at time of donor death. | Contact local hospitals, funeral homes, mortuaries, medical examiner’s offices, private pathology laboratories; if they cannot help, they may know someone who can. Refer to the harvest providers of other nearby donors’ plans. |

Periodically revisit brain donation plans. Identify back-up autopsy providers when creating plans if time allows it. |

| Brain harvest is Significantly delayed. | Keep the body in the funeral home’s cold room until the autopsy provider can arrive. Consider having the provider fix the tissue in formalin instead of trying to collect the brain fresh. |

Keep brain donatio plans updated. Make sure brain Harvesters are familiar with study protocol, and that they have the tools they need. |

| Clinical records for donor are incomplete. | Request records from health providers post-mortem; ask the next-of-kin for assistance if need be. | Keep regular follow-up of participants to collect clinical and research-specific data. |

Follow-up frequency.

Baseline clinical characteristics present an incomplete and often outdated picture of the donor, which may no longer be applicable at the time of death. Thus, regular follow-ups are necessary to update clinical information [J]. Donors may also develop new diagnoses that preclude their suitability for the study in which they are enrolled. Researchers should discuss such cases at length before deciding on whether to continue investing time and resources on a donor, or to ultimately exclude them from the study [K].

Brain banks should follow-up with donors as often as reasonably possible according to study resources, limitations, institutional review board guidance, and participant characteristics. Frequent contact not only allows for more clinical data collection, but also may improve retention and follow-up (Brueton et al. 2017). Coordinators can maintain contact by multiple means, including scheduled in-person clinical assessments, telephone or letter follow-ups, and emails, or more informal methods such as periodic newsletters, or birthday and holiday cards (Bell et al. 2008; Blanton et al. 2006; Brueton et al. 2017). Every occasion in which the donor is contacted should be seen as an opportunity to improve rapport by thanking enrollees for their participation in the study, providing them once again with the brain bank’s full contact information, and reminding them to inform the brain bank of any changes in their own contact information.

Although regular, planned follow-up is ideal, this is not always possible and follow-up periods may have to be adapted to any number of changing circumstances. Research goals, for example, can evolve over time and may require that the brain bank deviate from the original follow-up and recruitment strategies. A more problematic issue may be funding, which may not always be constant given the indefinite longitudinal nature of following brain donors; this can ultimately influence staff size, work load capacity, and the nature of the follow-ups themselves. Contingency plans should be made for these kinds of scenarios during which funding becomes more restrained, such as by decreasing the frequency of follow-up, adapting clinical assessments to be less resource-consuming, or temporarily halting recruitment of new donors. In any case, whichever strategy is found to best fit the aims of the brain bank, coordinators should never cease contacting participants entirely; if clinical follow-up cannot be established, at the very least contact information should be collected and updated regularly (Bell et al. 2008). In this way, obligations to the cohort, who signed up for a commitment-until-death, can be honored.

Clinical follow-up may be limited not just by the inherit constraints of a given study or brain bank, but by characteristics of the donor population. Donors may often have issues with follow-ups and can become annoyed if they are too frequent—especially if the assessment is taxing on them—, possibly compromising their willingness to participate in the study. Moreover, even when spaced out appropriately, strict periodic follow-ups will not always be achievable, as donors may want to delay for a myriad of reasons including health issues, scheduling problems, or sometimes simply not wanting to be bothered at a given moment. Although enrollees may wish and consent to be brain donors in a given study, the fact is that this is often a commitment of several years, which means that sometimes life simply gets in the way. As with clinical trials (Blanton et al. 2006), brain banks should be accommodating to the needs of their participants as long as doing so would not significantly compromise the quality of the research being conducted. Hence, the follow-up plan should always take donors and their families into consideration. Understanding the needs of donors and their families is key to fostering a good relationship with participants and achieving long-term follow-up.

Revisiting the brain donation plan.

Being a future brain donor is typically just one small facet of a person’s life, and this commitment is often the last thing on their mind in their day to day, especially when they are relatively healthy. As such, donors frequently fail to relay changes in their address or phone number to brain banks. As mentioned, it is in these occasions when having multiple contact persons is essential, particularly someone beyond the nuclear family to avoid possibly redundant telephone numbers or addresses. If additional contacts are lacking, donors might not reach out by their own accord until years later, which means years of missing data points for the study. Even worse, perhaps, it may occur that the next-of-kin reaches out only once the donor has passed, and the donation plans that had been made in the past are no longer possible.

The lives of donors can be far from static, and in fact, so too can all the other elements be in brain donation plans. Therefore, plans should be frequently revisited [L] to ensure they remain up to date and ready to be executed, a process which may require several hours per donor. For example, if a donor moves to a new city, coordinators will have to identify a new brain harvester and funeral home; other times, coordinators will find the original harvest provider has retired, or the hospital no longer assists with private autopsies because they are understaffed; perhaps the funeral home has decided to change their policy and is no longer willing to host the harvest in their embalming room. All such situations require time and effort from the brain bank coordinator to address by creating or adapting a new plan [M], and if this is not done before a donor’s death, it would have to be done afterwards at the expense of delaying the tissue’s arrival to the brain bank.

When reviewing brain donation plans, time should be set aside to address any questions or comments participants may have regarding the future donation, as sometimes they may develop some hesitations after their initial enrollment. Again, donors should be encouraged to speak with their families and friends about their decision, and an invitation should be extended to anyone who may be involved in the future donation process to contact the brain bank coordinator and voice their concerns about the brain procurement procedure. This should be emphasized during each follow-up, as ultimately the responsibility of informing brain banks of a donor’s death is thrust upon their next-of-kin and family; if they do not feel comfortable with the process, there is no guarantee that they will make the call at the time of death.

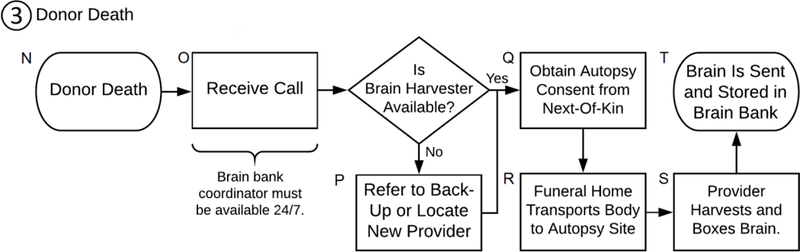

Donor Death [N –T]

The previously outlined efforts of enrolling interested participants, creating brain donation plans, and periodically following up with donors to update clinical information and to revisit plans all culminates with the death of the brain donor [N]. This is arguably the most crucial part of brain banking as there cannot be a brain bank if no brains are collected. When all pieces are properly in place, this “die-and-do” situation can in fact be quite anti-climactic, and the hours put into making a personalized brain donation plan simply translate into several brief telephone conversations between the brain bank coordinator and all other parties involved: coordinators obtain consent from the next-of-kin (a legal requirement in the United States), the funeral home transports the body to the brain removal site, and the harvest provider performs the harvest and packs the brain to be shipped. It is fairly common for the occasional kink to cause short delays in an otherwise well laid out plan, but when executed properly, autopsy should proceed smoothly in most cases. Even in those more troublesome cases, with enough effort, time, and persistence, the coordinator can usually see that the brain is successfully harvested, albeit with a corresponding delay.

Getting the call.

Brain procurement is a time-sensitive task, and thus requires immediate attention. When a donor dies, the first and most important step to a successful brain donation is for the brain bank coordinator to be informed of the donor’s passing as soon as possible [O]. This requires a coordinator to be available 24/7, and a form of communication such as a designated pager or cellphone to be at arm’s reach so he or she can be reached out to at a moment’s notice. Antiquated as they may be, pagers offer the advantage of a longer battery life compared to cellphones and so require minimal maintenance; however, modern callers may be unfamiliar with the use of pagers and thus, coordinators should record a greeting instructing such callers on how to input their call-back number. As emphasized, the brain bank’s contact information should be readily available to the donor’s family, and to anyone who may be involved in end-of-life decisions. The Essential Tremor Centralized Brain Repository handles this not only by sharing our contact information anew upon every communication we have with donors and their families, but also by including this information on our webpage, and by providing donors with stickers containing these details upon enrollment. We encourage our donors to share these stickers with their loved ones and physicians, and to place them in easy to remember places such as on their home refrigerator, in wallets, or stored in medical records.

First contact at the time of death is often made by the next-of-kin, but other family members, hospice staff, or health providers can also make this call. Brain bank coordinators should identify the caller, and verify the circumstances surrounding the donor’s death before putting the donation plan into action. Some callers may reach out to the brain bank coordinator before a participant’s actual passing, informing the coordinator of the donor’s critical health and providing a forewarning of their imminent passing; such occasions allow coordinators to alert everyone involved in the donation plan of the upcoming harvest.

Brain bank coordinators should contact the planned harvest provider to verify their availability. If they are unavailable, coordinators should refer to a back-up if one had previously been sought out, or locate a new harvester [P]. Identifying who will be performing the brain removal is necessary to obtain proper informed consent from the next-of-kin for the brain removal. If one cannot immediately be found, and in instances where the coordinator has not yet spoken to the next-of-kin, it is best to continue the search for a new provider once contact with the family and next-of-kin has been established. Coordinators should not delay contact with the donor’s family as it can be very distressing to not be in the loop of what is going to happen with their loved one’s brain donation. In these scenarios, brain bank coordinators should reassure the next-of-kin that efforts are being made to locate a new pathologist or technician, and that they will be informed of any advances every step of the way.

Speaking with the next-of-kin.

In the best scenarios, a donor’s death is expected and their plan will have been reviewed with the next-of-kin shortly before the donor’s passing; however, death can also come suddenly with little to no warning. Whether it is expected or not, the death of a loved one is a distressing time for the next-of-kin, and the coordinator must be able to guide the efforts needed for brain donation such that the task does not seem overwhelming to the family. After condolences are expressed, the consent process should be explained according to the study protocol and by going over the specific harvest plans for donation, including where the body will need to be taken and who will be performing the brain removal. Once informed consent is obtained [Q], coordinators should speak to the staff of the facility where the donor passed and request that ice packs be placed on and beneath the decedent’s head to start the cooling process for optimal tissue preservation.

Communication should be maintained with the next-of-kin throughout the entire procurement process to let them know the status of the brain donation and to reassure them that their loved one’s wishes are being carried out. The next-of-kin should be updated at crucial points such as when the body is transported anywhere, when the harvest is scheduled to proceed, and when the brain makes its way to the brain bank. Once this process is completed, the next-of-kin should be thanked for their assistance once more, as well as reminded of possible issues that may be pending such as obtaining the latest medical records and death certificate. We do not routinely send autopsy results to next-of-kin, as not all donors have next of kin who were vested in the process, and results can be technically-worded and challenging to understand. However, some families will ask for a copy of the autopsy results from the brain bank whenever they become available. This should be provided to them, with the explicit clarification that autopsy results on their own should not be interpreted in isolation. If requested, brain banks should provide insight about the final findings based on the donor information they have available, but banks should refer the family or next-of-kin to their treating physician if they have more clinically-oriented questions about how these results could impact their own health.

Speaking with the funeral home.

Ideally, families will have a pre-determined funeral home prior to the donor’s passing, allowing for the brain donation plan to have been coordinated with them ahead of time. Otherwise, plans will have to be adapted according to the capacities of the family’s newly chosen funeral home. The director is usually sympathetic towards the wish for brain donation and can be of great help in facilitating these efforts, either by lending the funeral home’s embalming room or by assisting with transportation [R]. Whatever service they provide, they should also be updated and informed about the donation process. If the brain bank is covering the full costs of the procurement (as is often the case when the procurement is part of a research study), this should be touched upon with the funeral home so that they do not accidently bill the family for services pertaining strictly to the harvest; this can lead to unnecessary stress and confusion for the family during a time when they need it least.

Speaking with the brain harvester.

Assuming the plan has been recently reviewed, the brain harvester should be familiar with the study protocol and will be able to harvest and prepare the brain for shipping [S]. In cases in which there needs to be a last-minute change in provider, it is important to go over the protocol with them in detail to ensure there are no questions regarding how the brain removal should be performed. If a new harvest provider is urgently needed to be found at the time of death, one may consider asking the funeral home director if they know of any provider that could be reached out to that may be willing to help; often they are experienced with these matters and can provide the information needed. Otherwise, local hospitals, medical examiners, county coroners, private pathology laboratories, other funeral homes, mortuaries, or distant providers from other plans may be able to help.

Harvest providers can either ship the brain themselves, or a courier service can be used to pick up and ship the brain to the bank for processing and storage [T]. Sufficient ice should be boxed with the brain to best preserve it during shipment. Some brain harvesters particularly pride themselves on the service they provide, and appreciate being informed of the brain’s arrival to the bank and the condition it arrived in. This post-mortem dialogue with the harvest provider can be particularly constructive when dealing with providers that may be participating in other future donations as well.

Conclusion

Brain banking is an arduous endeavor that requires careful planning to successfully execute. For those who are considering such an endeavor, they should know that long before the brain is received, much work must be performed to obtain clinical information that will complement the pathologic findings, as well as to coordinate all parties that will play a role in the harvest itself. These efforts must be repeated periodically to update clinical data and to ensure plans are still valid when donors are near death. The large number of cases that must be enrolled and then followed over time will dwarf the relatively small number who die each year. Organizing and following this large cohort requires much in the way of advanced planning and resources. With the right preparation, brain donation can proceed smoothly, and valuable clinical information and tissue will be obtained for study, thus leading to a better understanding of the disease of interest.

Figure 1.2.

Flowchart of the brain donation process: Donor Follow-Up

Figure 1.3.

Flowchart of the brain donation process: Donor Death

Acknowledgments

Funding.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, R01 NS086736, and R01 NS088257.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adler CH, Hentz JG, Joyce JN, Beach T, Caviness JN (2002) Motor impairment in normal aging, clinically possible Parkinson’s disease, and clinically probable Parkinson’s disease: longitudinal evaluation of a cohort of prospective brain donors Parkinsonism Relat Disord 9:103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias E, Heron M, Xu J (2017) United States Life Tables, 2014 Natl Vital Stat Rep 66:1– 64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi L, Garrick TM, Harper CG (2006) Brain donation for research: strong support in Australia J Clin Neurosci 13:449–452 doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2005.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes LL, Shah RC, Aggarwal NT, Bennett DA, Schneider JA (2012) The Minority Aging Research Study: ongoing efforts to obtain brain donation in African Americans without dementia Curr Alzheimer Res 9:734–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach TG et al. (2008) The Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program: description and experience, 1987–2007 Cell Tissue Bank 9:229–245 doi:10.1007/s10561-008-9067-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell KR, Hammond F, Hart T, Bickett AK, Temkin NR, Dikmen S (2008) Participant recruitment and retention in rehabilitation research Am J Phys Med Rehabil 87:330–338 doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e318168d092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes FM (2005) Ethical issues in brain banking Curr Opin Psychiatry 18:277–283 doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000165598.83305.4a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton S, Morris DM, Prettyman MG, McCulloch K, Redmond S, Light KE, Wolf SL (2006) Lessons learned in participant recruitment and retention: the EXCITE trial Phys Ther 86:1520–1533 doi:10.2522/ptj.20060091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boise L, Hinton L, Rosen HJ, Ruhl M (2017a) Will My Soul Go to Heaven If They Take My Brain? Beliefs and Worries About Brain Donation Among Four Ethnic Groups Gerontologist 57:719–734 doi:10.1093/geront/gnv683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boise L et al. (2017b) Willingness to Be a Brain Donor: A Survey of Research Volunteers From 4 Racial/Ethnic Groups Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 31:135–140 doi:10.1097/WAD.0000000000000174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes M, Ward P (2003) Brain donation for schizophrenia research: gift, consent, and meaning J Med Ethics 29:165–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brueton V, Stenning SP, Stevenson F, Tierney J, Rait G (2017) Best practice guidance for the use of strategies to improve retention in randomized trials developed from two consensus workshops J Clin Epidemiol 88:122–132 doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Sanchez FF, Mordini E, Ravid R (1997) Ethical aspects to be considered in brain banking Ann Ist Super Sanita 33:477–482 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Sanchez FF, Tolosa E (1993) The need of a consensus for brain banking J Neural Transm Suppl 39:1–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J, Everall IP, Lantos PL (1993) The contemporary AIDS database and brain bank--lessons from the past J Neural Transm Suppl 39:77–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange GM, Rademaker M, Boks MP, Palmen S (2017) Brain donation in psychiatry: results of a Dutch prospective donor program among psychiatric cohort participants BMC Psychiatry 17:347 doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1513-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira KC et al. (2012) Brazilian psychiatric brain bank: a new contribution tool to network studies Cell Tissue Bank 13:315–326 doi:10.1007/s10561-011-9258-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW (2005) Required techniques and useful molecular markers in the neuropathologic diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases Acta Neuropathol 109:14–24 doi:10.1007/s00401-004-0950-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eatough V, Shaw K, Lees A (2012) Banking on brains: insights of brain donor relatives and friends from an experiential perspective Psychol Health 27:1271–1290 doi:10.1080/08870446.2012.669480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrick T, Azizi L, Merrick J, Harper C (2003) Brain donation for research, what do people say? Intern Med J 33:475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrick T, Howell S, Terwee P, Redenbach J, Blake H, Harper C (2006) Brain donation for research: who donates and why? J Clin Neurosci 13:524–528 doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2005.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrick T, Sundqvist N, Dobbins T, Azizi L, Harper C (2009) Factors that influence decisions by families to donate brain tissue for medical research Cell Tissue Bank 10:309–315 doi:10.1007/s10561-009-9136-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillman A, Babij R, Lee M, Moskowitz C, Faust PL, Louis ED (2014) Reflections: neurology and the humanities. Odd harvest Neurology 82:184–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaw XM, Garrick TM, Terwee PJ, Patching JR, Blake H, Harper C (2009) Brain donation: who and why? Cell Tissue Bank 10:241–246 doi:10.1007/s10561-009-9121-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeber MB (2008) Twenty-first century brain banking: at the crossroads Acta Neuropathol 115:493–496 doi:10.1007/s00401-008-0363-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinberg LT et al. (2007) Brain bank of the Brazilian aging brain study group - a milestone reached and more than 1,600 collected brains Cell Tissue Bank 8:151– 162 doi:10.1007/s10561-006-9022-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavson K, von Soest T, Karevold E, Roysamb E (2012) Attrition and generalizability in longitudinal studies: findings from a 15-year population-based study and a Monte Carlo simulation study BMC Public Health 12:918 doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon SH, McMahon A (2014) Banking (on) the brain: from consent to authorisation and the transformative potential of solidarity Med Law Rev 22:572–605 doi:10.1093/medlaw/fwu011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroutunian V, Pickett J (2007) Autism brain tissue banking Brain Pathol 17:412–421 doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00097.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris C, Kiger A, Counsell C (2013) Attitudes to brain donation for Parkinson’s research and how to ask: a qualitative study with suggested guidelines for practice J Adv Nurs 69:1096–1108 doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06099.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins AK (2010) Biobanks: importance, implications and opportunities for genetic counselors J Genet Couns 19:423–429 doi:10.1007/s10897-010-9305-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulette CM (2003) Brain banking in the United States J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 62:715– 722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson AL, Lambe S, Cook E, Pimontel M, Palmisano J, Chaisson C (2011) Factors associated with African American and White elders’ participation in a brain donation program Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 25:11–16 doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f3e059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson AL, Lambe S, Romano RR, Liu D, Islam F, Kowall N (2013) An intervention to enhance Alzheimer’s disease clinical research participation among older African Americans J Alzheimers Dis 36:597–606 doi:10.3233/JAD-130287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirch DG, Wagman AM, Goldman-Rakic PS (1991) Commentary: the acquisition and use of human brain tissue in neuropsychiatric research Schizophr Bull 17:593–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhta T, Zadikoff C, Simuni T, Martel A, Williams K, Videnovic A (2011) Brain donation--what do patients with movement disorders know and how do they feel about it? Parkinsonism Relat Disord 17:204–207 doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambe S, Cantwell N, Islam F, Horvath K, Jefferson AL (2011) Perceptions, knowledge, incentives, and barriers of brain donation among African American elders enrolled in an Alzheimer’s research program Gerontologist 51:28–38 doi:10.1093/geront/gnq063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim A et al. (1999) Clinico-neuropathological correlation of Alzheimer’s disease in a community-based case series J Am Geriatr Soc 47:564–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis ED, Borden S, Moskowitz CB (2005) Essential tremor centralized brain repository: diagnostic validity and clinical characteristics of a highly selected group of essential tremor cases Mov Disord 20:1361–1365 doi:10.1002/mds.20583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis ED, Levy G, Cote LJ, Mejia H, Fahn S, Marder K (2002) Diagnosing Parkinson’s disease using videotaped neurological examinations: validity and factors that contribute to incorrect diagnoses Mov Disord 17:513–517 doi:10.1002/mds.10119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DD, Ravina B (2003) Brain banking for neurodegenerative diseases Curr Opin Neurol 16:459–463 doi:10.1097/01.wco.0000084222.82329.f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padoan CS et al. (2017) “Why throw away something useful?”: Attitudes and opinions of people treated for bipolar disorder and their relatives on organ and tissue donation Cell Tissue Bank 18:105–117 doi:10.1007/s10561-016-9601-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer-Aronsten B, Sheedy D, McCrossin T, Kril J (2016) An International Survey of Brain Banking Operation and Characterization Practices Biopreserv Biobank 14:464–469 doi:10.1089/bio.2016.0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey GN, Dwivedi Y (2010) What can post-mortem studies tell us about the pathoetiology of suicide? Future Neurol 5:701–720 doi:10.2217/fnl.10.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porteri C, Borry P (2008) A proposal for a model of informed consent for the collection, storage and use of biological materials for research purposes Patient Educ Couns 71:136–142 doi:10.1016/j.pec.2007.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez EPC, Keller CE, Vonsattel JP (2018) The New York Brain Bank of Columbia University: practical highlights of 35 years of experience Handb Clin Neurol 150:105–118 doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63639-3.00008-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravid R, Ikemoto K (2012) Pitfalls and practicalities in collecting and banking human brain tissues for research on psychiatric and neulogical disorders Fukushima J Med Sci 58:82–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarasekera N et al. (2013) Brain banking for neurological disorders The Lancet Neurology 12:1096–1105 doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70202-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt FA, Wetherby MM, Wekstein DR, Dearth CM, Markesbery WR (2001) Brain donation in normal aging: procedures, motivations, and donor characteristics from the Biologically Resilient Adults in Neurological Studies (BRAiNS) Project Gerontologist 41:716–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnieders T, Danner DD, McGuire C, Reynolds F, Abner E (2013) Incentives and barriers to research participation and brain donation among African Americans Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 28:485–490 doi:10.1177/1533317513488922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M (1998) Factors influencing decisions about donation of the brain for research purposes Age Ageing 27:623–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopa EG, Bird ED (1989) Brain donation N Engl J Med 320:62–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strous RD, Bergman-Levy T, Greenberg B (2012) Postmortem brain donation and organ transplantation in schizophrenia: what about patient consent? J Med Ethics 38:442–444 doi:10.1136/medethics-2011-100217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundqvist N, Garrick T, Harding A (2012) Families’ reflections on the process of brain donation following coronial autopsy Cell Tissue Bank 13:89–101 doi:10.1007/s10561-010-9233-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonsattel JP, Amaya Mdel P, Cortes EP, Mancevska K, Keller CE (2008a) Twenty-first century brain banking: practical prerequisites and lessons from the past: the experience of New York Brain Bank, Taub Institute, Columbia University Cell Tissue Bank 9:247–258 doi:10.1007/s10561-008-9079-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonsattel JP, Del Amaya MP, Keller CE (2008b) Twenty-first century brain banking. Processing brains for research: the Columbia University methods Acta Neuropathol 115:509–532 doi:10.1007/s00401-007-0311-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, Burr G (2002) Why families deny consent to organ donation Aust Crit Care 15:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]