Abstract

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) persists in the combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) era and is associated with diminished quality of life. The disorder remains challenging to diagnose given the requirement for comprehensive neuropsychological testing. Blood biomarkers are needed to facilitate the diagnosis of HAND and to gauge neurological response to antiretroviral therapy. We performed a study of plasma neurofilament light chain (NFL) that included 37 HIV-infected and 54 HIV-negative adults. In the univariate mixed effects model involving HIV-infected participants, there was a statistically significant linear relationship between composite neuropsychological score (NPT-11) and plasma NFL (slope = −9.9; standard error = 3.0 with 95% confidence interval: −3.2 to −16.6 and p =0.008 when testing slope = 0). Similarly, in the multivariate mixed effects model, higher plasma NFL was significantly associated with worse NPT-11 (slope = −11.5; standard error = 3.3 with 95% confidence interval: −3.7 to −19.0 and p=0.01 when testing slope = 0). The association between NPT-11 and NFL appeared to be driven by the group of individuals off cART. In a subset of participants who had visits before and after 24 weeks on cART (n=11), plasma NFL declined over time (median= 22.7 versus 13.4 pg/ml, p= 0.02). In contrast, plasma NFL tended to increase over time among HIV-negative participants (median 10.3 versus 12.6 pg/ml, p=0.065, n=54). Plasma NFL therefore shows promise as a marker of neuropsychological performance during HIV. Larger studies are needed to determine if NFL could serve as a diagnostic tool for HAND during suppressive cART.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, neurofilament, cognitive impairment

Introduction

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) continues to occur in the combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) era. Even in large cohorts of individuals who have achieved virologic suppression, HAND prevalence is over 40% (Heaton et al, 2010). Health-related quality of life scores for individuals with HAND are significantly lower than for HIV-infected individuals without HAND (Tozzi et al, 2003). Even in the cART era, the hazard ratio for mortality is 3.1 for patients with HAND compared to HIV-infected patients without HAND (Vivithanaporn et al, 2010).

The current approach to HAND diagnosis requires comprehensive neuropsychological testing, which is not feasible in many clinical settings. More research is needed on biomarkers that could facilitate the rapid diagnosis of HAND and at the same time provide a window into HIV neuropathogenesis. While multiple biomarkers have been linked to HAND, one of the most promising is neurofilament light chain (NFL). NFL is a major structural component of axons and is thus a marker of neuronal injury. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of NFL are elevated in the setting of HIV-associated dementia (Abdulle et al, 2007; Jessen Krut et al, 2014).

While lumbar puncture is a safe procedure, it is more time-consuming and difficult to integrate into a busy clinic than venipuncture. A recently published cross- sectional study showed that NFL can be accurately measured in plasma and correlates strongly with CSF NFL in HIV-infected individuals (Gisslen et al, 2016). Plasma NFL concentrations were particularly high in individuals with HIV-associated dementia off cART. In the current study, our aim was to examine plasma NFL during milder HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment, as well as change with initiation of cART. For comparison, we also analyzed a cohort of HIV-negative individuals who had two visits over time.

Methods

HIV-infected (HIV+) adults enrolled between 2011 and 2014 at the Emory University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) clinical core site in Atlanta as part of ongoing studies on HIV and neurocognition. Exclusion criteria were: 1) history of any neurologic disease other than HIV that is known to affect memory (including stroke, malignancy involving the brain, traumatic brain injury, and AIDS-related opportunistic infection of the central nervous system); 2) active substance use (marijuana use in the last 7 days OR cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, or other non-marijuana illicit drug use in the last 30 days); 3) heavy alcohol consumption in the last 30 days (defined as >7 drinks per week for women and >14 drinks per week for men); or 4) serious mental illness including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (depression was not excluded if participants were well controlled on treatment). Lastly, participants were excluded if cognitive symptoms had rapidly progressed in the past 30 days so that medical evaluation could be undertaken.

In addition to the HIV Dementia Scale, a comprehensive neuropsychological (NP) testing battery was administered to the HIV+ participants that included eleven tests used commonly in studies of cognition and HIV infection (Robertson and Yosief, 2014): 1) Trailmaking Part A; 2) Trailmaking Part B; 3) Hopkins Verbal Learning Test total learning; 4) Hopkins Verbal Learning Test delayed recall; 5) Grooved Pegboard (dominant) 6) Grooved Pegboard (nondominant); 7) Stroop Color Naming, 8) Stroop Color-Word interference; 9) Symbol Digit Modalities Test; 10) Letter Fluency (Controlled Oral Word Association Test), and 11) Category fluency (animals). These tests were selected in order to examine at least five domains as recommended in the most recent nosology of HAND criteria (Antinori et al, 2007). Scores were adjusted for demographic characteristics (including age, sex, race, and education) using published norms (Heaton et al, 2004). A composite global mean T score (NPT-11) was then calculated by average of individual T scores. Global Deficit Score (GDS), a validated measure of neurocognitive impairment in HIV based on demographically corrected T scores, was used as a binary cutoff for neurocognitive impairment (GDS > 0.5) (Carey et al, 2004). A subset of participants who were off cART at baseline had a second visit 24– 48 weeks after starting therapy, at which time the NP battery was repeated. Score adjustment for practice effects was made for longitudinal visits by published methods (Cysique et al, 2011).

A group of HIV-negative individuals were enrolled as part of ongoing projects from 2003 to 2013 at the HIV-Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) at the University of California at San Diego. These projects included studies on the effects of distant methamphetamine use. Seronegative HIV status was confirmed at study baseline using commercially available antibody tests. Individuals were excluded for any of the following characteristics: 1) Serious neuropsychiatric comorbidities that could affect cognition including traumatic brain injury, schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, stroke, or seizure disorder, 2) Substance abuse or dependence in the previous five years, and 3) History of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection or a positive HCV antibody test (performed on all participants). Full NP data was available on a subset of the HIV-negative participants, specifically for the following seven individual tests: 1) Hopkins Verbal Learning Test learning; 2) Hopkins Verbal Learning Test delayed recall; 3) Brief Visuospatial Memory Test learning, 4) Brief Visuospatial Memory Test delayed recall, 5) Wisconsin Card Sorting Test-64, 6) Stroop Color Naming, and 7) Stroop Color Word Interference. Like the HIV+ participants, a composite global mean T score (NPT-7) was then calculated by average of individual T scores, and score adjustments for practice effects were made for longitudinal visits. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both institutions and written consent was obtained from all participants.

HIV RNA was measured from plasma and CSF at the Emory Center for AIDS Research Virology Core using the Abbott Laboratories m2000 Real Time HIV-1 assay system (reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, lowest limit of detection of 40 copies/ml). Plasma NFL concentrations (and CSF concentrations in a subset of participants) were measured using an in house digital enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay on a Single molecule array (Simoa) platform (Quanterix, Lexington, MA), as previously described: (Gisslen el al, 2016; Rohrer el al, 2016). The measurements were performed in one round of experiments using one batch of reagents by board-certified laboratory technicians who were blinded to clinical information. Intra-assay coefficients of variation were below 10%. The univariate statistical analyses were performed with SAS JMP version 13 as well as Graphpad Prism 6. For mixed effects and multivariate analyses, SAS version 9.4 was used. Normality of continuous variables was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Correlations were performed using Spearman’s rho test, unless normality conditions were met, in which case Pearson’s r test was used. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for paired continuous variables, unless normality conditions were met, in which case the paired t-test was used. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical results between groups. Linear regression was performed to determine the relationship between plasma NFL and NPT-11 in the HIV+ group at baseline based on cART status. To incorporate longitudinal visits, degree of NPT-11 decline was then obtained using a mixed-effects linear model specifying that NPT-11 follows a linear regression over NFL, with random intercept for each participant. The first model examined only logio plasma NFL as a covariate for the outcome of NPT-11. In the second model, age, current CD4+ T-cell count, and logio plasma HIV RNA concentration were additionally included given their previously reported association with HAND (McArthur et al, 1997; Robertson et al, 2007; Saylor et al, 2016; Valcour et al, 2006). To account for collinearity with CD4+ T-cell count, plasma HIV RNA was categorized as a binary variable (detectable/undetectable). The SAS MIXED Procedure was used to fit the models and estimate the degree of NPT-11 decline and its standard error and 95% confidence interval in the presence of other covariates. Goodness of fit was estimated by the second order Akaike Information Criterion (AICc). Alpha level for significance was set at <0.05 and was two tailed.

Results

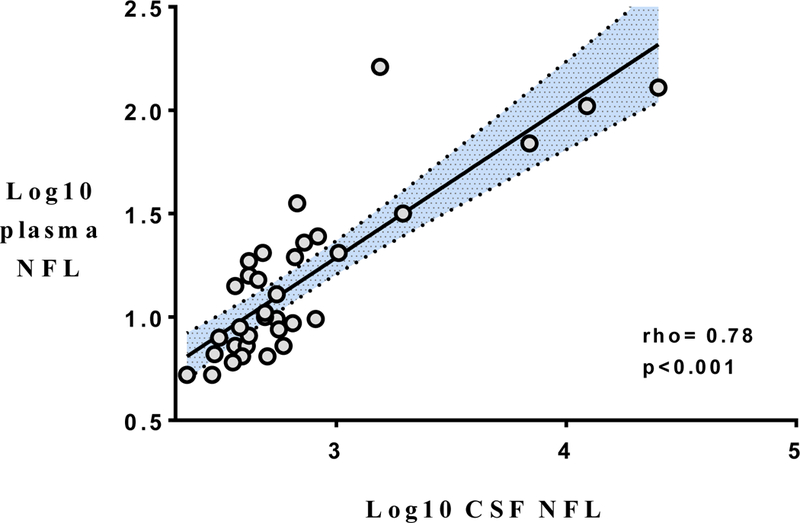

Thirty-seven HIV+ adults were analyzed (table 1). Participants were mostly male (78%) and African-American (62%). Median estimated duration of HIV infection was 11 years (25%- 75% interquartile range [IQR]= 4–22 years). There were 21 participants (57% overall) who were on three-drug cART with plasma HIV RNA < 40 copies/milliliter (ml) for at least six months at baseline. Ten were on protease-inhibitor (PI) based regimens (six atazanavir, two lopinavir, one darunavir, and one fosamprenavir); four were on Non-nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor (NNRTI) based regimens (all efavirenz); two were on Integrase Inhibitor based (II) regimens (one elvitegravir and one raltegravir); and five were on more than one PI/NNRTI/Π backbone drug (for example, one participant was on both darunavir and raltegravir). The remaining 16 participants were off antiretrovirals for at least six months (including seven who were antiretroviral naive) and had a median plasma HIV RNA of log10 5.0 (IQR= log10 4.0–5.4). Four participants were hepatitis C virus (HCV) seropositive with confirmatory positive HCV RNA, while two participants were positive for chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen (HbsAg). Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was negative on all participants. Median HIV Dementia Scale score at baseline was 14 of 16 (IQR= 11–16). Mean NPT-11 score at baseline was 45.0 (Standard deviation [SD]= 8.0). Median GDS was 0.64 (IQR 0.14–0.91). In the subset of participants with CSF results available at baseline (n=34), log10 plasma NFL concentration correlated significantly with log10 CSF NFL concentration (rho= 0.78, p<0.001, see fig. 1 with regression line and 95% confidence interval).

Table 1:

Demographic and Disease characteristics of HIV+ participants.

| Variable (N=37) |

Median (IQR) or Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age in years | 48 (41.5–50.5) |

| Male Sex | 29 (78%) |

| Race | |

| African American | 23 (62%) |

| White | 13 (35%) |

| Native American | 1 (3%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Hypertension | 10 (27%) |

| Depression | 6 (16%) |

| Hepatitis C co-infection | 4(11%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 3 (8%) |

| Peripheral Neuropathy | 3 (8%) |

| NP testing | |

| Mean NPT-11 | 45.0 |

| GDS ≥0.5 | 22 (59%) |

| Blood Tests | |

| CD4+ Current (per μl) | 313 (60–448) |

| CD4+ Nadir (n=34, per μl) | 50 (19–124) |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.9 (0.8–1.2) |

| Plasma NFL (pg/ml) | 10.0 (7.3–20.6) |

| Plasma HIV RNA < 40 | |

| copies/ml on cART | 21 (57%) |

| CSF Tests (n=34) | |

| WBC (per μl) | 0 (0–4) |

| RBC (per μl) | 0(0–1) |

| Protein (mg/dl) | 39 (31–55) |

| NFL (pg/ml) | 497 (387–743) |

IQR= interquartile range; NP= neuropsychological; GDS= global deficit score; CD= cluster of differentiation, pl= microliter; mg= milligrams; dl= deciliters; pg= picograms; ml= milliliters; NFL= Neurofilament light chain; HIV= human immunodeficiency virus; RNA= ribonucleic acid; cART= combination antiretroviral therapy; CSF= cerebrospinal fluid; WBC= white blood cell count; RBC= red blood cell count.

Figure 1.

NFL= neurofilament light chain CSF= cerebrospinal fluid

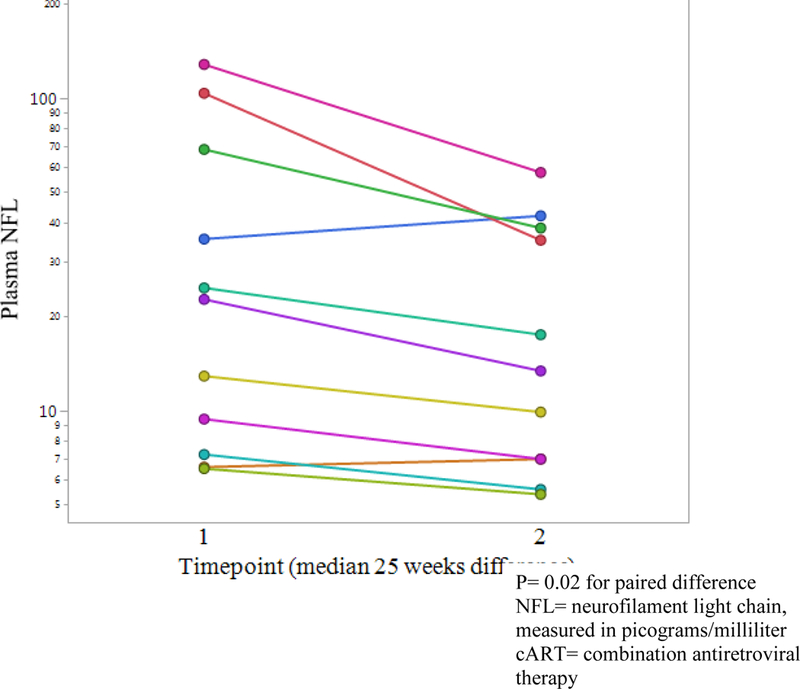

Eleven of the 16 HIV+ participants who were off cART at baseline had a second study visit at least 24 weeks after starting cART (median 28 weeks after therapy initiation, IQR= 25–30 weeks). Plasma HIV RNA declined at least 1.0 log10 plasma HIV RNA in 9 of 11 (82%). NPT- 11 significantly improved (visit 1 mean= 41.6 versus visit 2 mean= 46.3, p= 0.001). Concurrently, plasma NFL concentration significantly decreased (see fig. 2, presented in log scale) among these eleven participants (visit 1 median= 22.7 picograms/milliliter [pg/ml] versus visit 2 median= 13.4 pg/ml, p= 0.02).

Figure 2:

Plasma NFL change with cART initiation

For the HIV+ participants at baseline (n=37), the negative correlation between plasma NFL and NPT-11 was not statistically significant (rho= - 0.23, p= 0.17). The relationship between plasma NFL and NPT-11 was stronger among participants off cART at baseline. Specifically, the linear regression equation was = 54.27 + (−8.5263)(X), p= 0.036 for the 16 HIV+ participants off cART at baseline, while the equation was = 44.54 + (1.685)(X), p=0.83 for the 21 HIV patients on cART at baseline (p values refer to null hypothesis that slope= 0). In the univariate mixed effects model incorporating longitudinal visits, however, there was a statistically significant negative linear relationship between NPT-11 and plasma NFL (slope = - 9.9; standard error = 3.0 with 95% confidence interval: −3.2 to −16.6 and p =0.008 when testing slope = 0, AICc =314.0). Similarly, in the multivariate mixed effects model, higher plasma NFL was significantly associated with worse NPT-11 (slope = −11.5; standard error = 3.3, 95% confidence interval: −19.0 to −3.7 and p=0.01 when testing slope = 0, AICc= 317.1). Therefore, for each 0.50 log10 increase in NFL, NPT-11 worsened by 5.8 points. Age (p= 0.16), CD4 T-cell count (p = 0.67) and plasma HIV RNA concentration (p = 0.37 for detectable versus non- detectable) were not related to NPT-11 in the model.

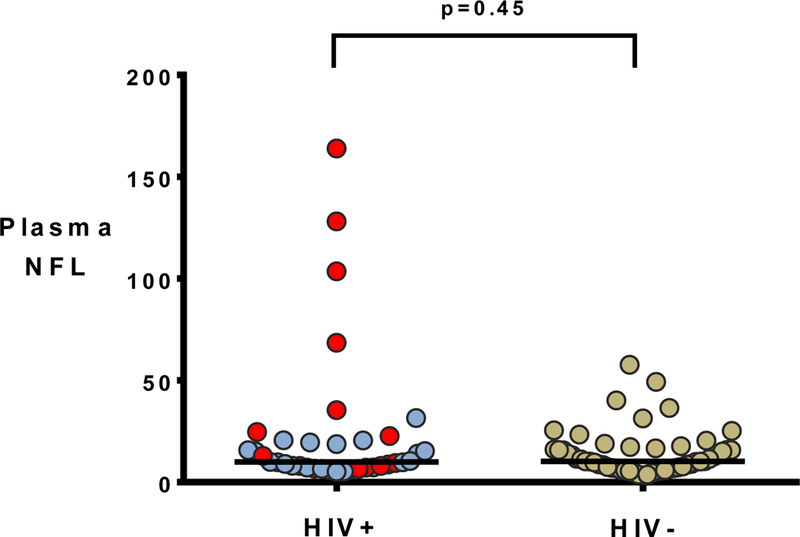

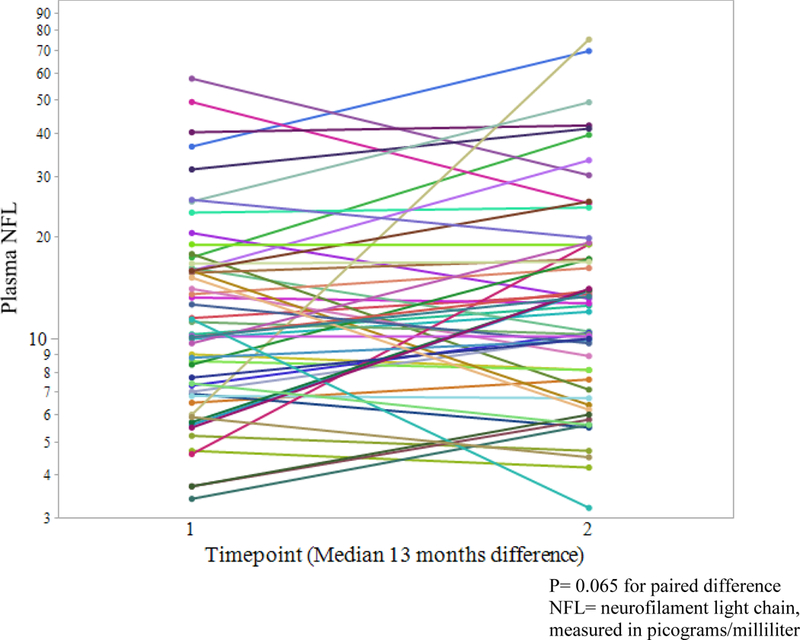

For the longitudinal HIV-negative analysis, samples from 54 randomly selected HIVnegative participants with two visits were analyzed. For this group, median age was 36.5 years (IQR= 24–48) and 78% were male. Race/ethnicity was 42.6% white, 27.8% Hispanic, 22.2% African-American, and 7.4% other races/ethnicities. HIV-negative participants at baseline were therefore younger (p<0.001) and less likely to be black (p<0.001) than HIV+ participants. Median plasma NFL at baseline was 10.3 pg/ml (IQR 6.9– 16.2) in the HIV-negatives, which was not significantly different (p= 0.45) than HIV+ participants at baseline (see fig. 3). While none of the participants in either group were currently abusing or dependent on illicit drugs, 18 of 52 HIV-negative participants for whom data was available (34.6%) had a distant history of methamphetamine dependence (versus 0% of the HIV+ group, p<0.001). Median time between baseline and the second visit was 13 months (IQR 12–14 months) among the 54 HIV-negative participants. While not a statistically significant change, plasma NFL tended to increase over this period of time (second visit median 12.6 pg/ml, IQR 7.5–19.0, p=0.065, fig. 4). 38 of the HIVnegative participants had full NP data available to generate the NPT-7, including 28 of whom had the same testing at a second (total of 66 visits). To take advantage of all data points (as with the HIV+ participants), linear mixed modeling was performed with plasma NFL as the independent variable and NPT-7 as the dependent variable. The equation for this model was = 48.55 + (−1.1428)(X), where the standard error for the slope was ± 2.914. The P value for this slope when compared to the null hypothesis that slope=0 was 0.70.

Figure 3.

N F L= neurofilament light chain, measured in picograms/ml horizontal line= median Red dots indicate individuals off treatment

Figure 4:

Plasma NFL longitudinal change in HIV negatives

Discussion

With HAND remaining highly prevalent in the cART era, more tools are needed to better understand and diagnose this disorder. Since venipuncture is more readily available and is associated with fewer side effects than lumbar puncture, a blood test that reflects neuropsychological performance during HIV would be a significant advance. In this exploratory study of HIV-infected adults, we found that higher plasma NFL concentration was significantly associated with worse neuropsychological performance in univariate and multivariate modeling that accounted for age, CD4+ T cell count, and plasma HIV RNA level. Most HIV-infected individuals with HAND in the cART era have mild disease, and this was true in our study. Using the GDS criteria for severe impairment of 1.5, only three of 37 participants (8%) were severely impaired. Therefore, plasma NFL could be a marker of not just HIV-dementia, but potentially milder forms of HAND as well. However, the association between plasma NFL and NP performance in the HIV+ group appeared to be driven by the individuals who were off cART.

Plasma NFL concentrations did not differ significantly between HIV+ and HIV-negative participants in this study, but the small sample size and the fact that many HIV+ participants did not have impairment may have played a role in this. Additionally, over one third of the HIVnegative group had a history of methamphetamine dependence. Given that methamphetamine has been shown to signal pro-death apoptotic pathways in the neuron (Jimenez et al, 2004; Wu et al, 2007), it is possible that NFL levels in this group could have been artificially elevated due to a history of chronic methamphetamine use. Using similar mixed effects modeling that incorporated longitudinal visits, we did not find a significant association between plasma NFL and NP performance in the HIV-negative group.

In a small subset of HIV+ participants who were followed longitudinally after starting cART, plasma NFL decreased significantly, which is a similar finding to the decrease in NFL that occurs in CSF after cART initiation (Jessen Krut et al, 2014). This suggests that neuronal damage is at least partially ameliorated by cART, which is consistent with studies that have shown improvement in neuropsychological function after cART initiation (Cysique et al, 2009). In contrast, there was a trend towards longitudinal increase in plasma NFL in the group of HIVnegative participants, though this was not statistically significant. A relationship between increasing age and increasing NFL has been found in other studies (Jessen Krut et al, 2014; Yilmaz et al, 2017), and therefore may reflect neuronal damage over time. Plasma NFL concentrations also correlated closely with CSF NFL concentrations, confirming the findings of a recent study (Gisslen et al, 2016) and supporting the conclusion that plasma NFL reflects neuronal injury in the CNS during HIV.

We acknowledge the limitations of this exploratory study, including its small sample size. The univariate and multivariate models were comprised of a relatively small number of individuals, but results were similar and model diagnostics were not indicative of overfitting. We acknowledge that the associations were only significant with the inclusion of repeated measures from the participants with a second visit after initiation of cART. Lastly, given that many of the study participants were not on cART, the results may not be generalizable to the HIV+ population on long-term, effective cART. For this reason, the study should be considered a first step in the evaluation of plasma NFL as a marker of HAND. A larger study focusing on individuals with virologic suppression is needed to determine if plasma NFL is associated with neuropsychological performance during effective cART and to further evaluate plasma NFL as a clinically useful biomarker of HAND.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grants from the Swedish and European Research Councils, Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (ALFGBG), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Torsten Soderberg Foundation, NIH K23MH095679, NIH K24MH097673, and P30AI050409 (Emory Center for AIDS Research).

References

- Abdulle S, Mellgren A, Brew BJ, Cinque P, Hagberg L, Price RW, Rosengren L, Gisslen M (2007). CSF neurofilament protein (NFL) -- a marker of active HIV-related neurodegeneration. J Neurol 254: 1026–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V, Wojna VE (2007). Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology 69: 1789–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey CL, Woods SP, Gonzalez R, Conover E, Marcotte TD, Grant I, Heaton RK, Group H (2004). Predictive validity of global deficit scores in detecting neuropsychological impairment in HIV infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 26: 307–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cysique LA, Franklin D Jr, Abramson I, Ellis RJ, Letendre S, Collier A, Clifford D, Gelman B, McArthur J, Morgello S, Simpson D, McCutchan JA, Grant I, Heaton RK, Group C, Group H (2011). Normative data and validation of a regression based summary score for assessing meaningful neuropsychological change. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 33: 505–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cysique LA, Vaida F, Letendre S, Gibson S, Cherner M, Woods SP, McCutchan JA, Heaton RK, Ellis RJ (2009). Dynamics of cognitive change in impaired HIV-positive patients initiating antiretroviral therapy. Neurology 73: 342–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisslen M, Price RW, Andreasson U, Norgren N, Nilsson S, Hagberg L, Fuchs D, Spudich S, Blennow K, Zetterberg H (2016). Plasma Concentration of the Neurofilament Light Protein (NFL) is a Biomarker of CNS Injury in HIV Infection: A Cross-Sectional Study. EBioMedicine 3: 135–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, Vigil OR, Taylor MJ, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J, Grant I, Group C (2010). HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology 75: 2087–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Miller SW, Taylor MJ, Grant I (2004). Revised Comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead- Reitan Battery: Demographically adjusted neuropsycho- logical norms for African American and Caucasian adults scoring program (2004).

- Jessen Krut J, Mellberg T, Price RW, Hagberg L, Fuchs D, Rosengren L, Nilsson S, Zetterberg H, Gisslen M (2014). Biomarker evidence of axonal injury in neuroasymptomatic HIV-1 patients. PLoS One 9: e88591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez A, Jorda EG, Verdaguer E, Pubill D, Sureda FX, Canudas AM, Escubedo E, Camarasa J, Camins A, Pallas M (2004). Neurotoxicity of amphetamine derivatives is mediated by caspase pathway activation in rat cerebellar granule cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 196: 223–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur JC, McClernon DR, Cronin MF, Nance-Sproson TE, Saah AJ, St Clair M, Lanier ER (1997). Relationship between human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia and viral load in cerebrospinal fluid and brain. Ann Neurol 42: 689–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson K, Yosief S (2014). Neurocognitive assessment in the diagnosis of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Semin Neurol 34: 21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson KR, Smurzynski M, Parsons TD, Wu K, Bosch RJ, Wu J, McArthur JC, Collier AC, Evans SR, Ellis RJ (2007). The prevalence and incidence of neurocognitive impairment in the HAART era. AIDS 21: 1915–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer JD, Woollacott IO, Dick KM, Brotherhood E, Gordon E, Fellows A, Toombs J, Druyeh R, Cardoso MJ, Ourselin S, Nicholas JM, Norgren N, Mead S, Andreasson U, Blennow K, Schott JM, Fox NC, Warren JD, Zetterberg H (2016). Serum neurofilament light chain protein is a measure of disease intensity in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 87: 1329–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor D, Dickens AM, Sacktor N, Haughey N, Slusher B, Pletnikov M, Mankowski JL, Brown A, Volsky DJ, McArthur JC (2016). HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder--pathogenesis and prospects for treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 12: 234–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi V, Balestra P, Galgani S, Murri R, Bellagamba R, Narciso P, Antinori A, Giulianelli M, Tosi G, Costa M, Sampaolesi A, Fantoni M, Noto P, Ippolito G, Wu AW (2003). Neurocognitive performance and quality of life in patients with HIV infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 19: 643–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcour V, Yee P, Williams AE, Shiramizu B, Watters M, Selnes O, Paul R, Shikuma C, Sacktor N (2006). Lowest ever CD4 lymphocyte count (CD4 nadir) as a predictor of current cognitive and neurological status in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection--The Hawaii Aging with HIV Cohort. J Neurovirol 12: 387–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivithanaporn P, Heo G, Gamble J, Krentz HB, Hoke A, Gill MJ, Power C (2010). Neurologic disease burden in treated HIV/AIDS predicts survival: a population-based study. Neurology 75: 1150–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CW, Ping YH, Yen JC, Chang CY, Wang SF, Yeh CL, Chi CW, Lee HC (2007). Enhanced oxidative stress and aberrant mitochondrial biogenesis in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells during methamphetamine induced apoptosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 220: 243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz A, Blennow K, Hagberg L, Nilsson S, Price RW, Schouten J, Spudich S, Underwood J, Zetterberg H, Gisslen M (2017). Neurofilament light chain protein as a marker of neuronal injury: review of its use in HIV-1 infection and reference values for HIV-negative controls. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 17: 761–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]