Abstract

Plasma HIV RNA level has been shown to correlate with HIV disease progression, morbidity and mortality. We examined the association between levels of plasma HIV RNA and cognitive function among patients in Nigeria. A total of 179 HIV-1 infected participants with available plasma HIV RNA results and followed longitudinally for up to 2 years were included in this study. Blood samples from participants were used for the measurement of plasma HIV RNA and CD4+ T cell count. Utilizing demographic and practice effect adjusted T scores obtained from a 7-domain neuropsychological test battery, cognitive status was determined by the global deficit score (GDS) approach, with a GDS ≥ 0.5 indicating cognitive impairment. In a longitudinal multivariable linear regression analysis, adjusting for CD4 cell count, Beck’s depression score, age, gender, years of education, and antiretroviral treatment status, global T scores decreased by 0.35 per log10 increase in Plasma HIV RNA [p=0.033]. Adjusting for the same variables in a multivariable logistic regression, the odds of neurocognitive impairment were 28% higher per log10 increase in plasma HIV RNA (OR: 1.28 [95% CI: 1.08, 1.51]; p=0.005). There were statistically significant associations for the speed of information processing, executive and verbal fluency domains in both linear and logistic regression analyses. We found a significant association between plasma HIV RNA levels and cognitive function in both baseline (cross-sectional) and longitudinal analyses. However, the latter was significantly attenuated due to weak association among antiretroviral-treated individuals.

Keywords: Plasma HIV RNA Cognitive function Nigeria

Introduction

While the incidence of severe forms of HIV associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) has declined remarkably following the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), milder forms persist with high prevalence (Heaton et al. 2010).

As a sine qua non in the etiopathogenesis of HAND, the HIV virus gains entry to the central nervous system (CNS) mainly through trafficking within infected mononuclear cells (Gonzalez-Scarano and Martin-Garcia 2005). This leads to a cascade of inflammatory events that result in neural damage.(Rao et al. 2014) Progressive neural damage in the brain, attributable directly to the virus or the inflammatory response it induces, results in the neurological syndrome of HAND (Antinori et al. 2007).

Levels of plasma HIV RNA, the traditional indicator for viral replication, has been shown to correlate with HIV disease progression, morbidity and mortality (Mellors et al. 1996). However, studies have not consistently demonstrated a significant association between plasma HIV RNA and HAND, particularly among patients on cART (Heaton et al. 2011). In contrast, levels of HIV RNA within the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) appear to correlate better with HAND (Ellis et al. 1997; Robertson et al. 1998; Ellis et al. 2002).

Most of the studies failing to show significant association between HAND and plasma HIV RNA were either cross-sectional in design or had relatively small sample sizes (Robertson et al. 1998; Stankoff et al. 1999; Ellis et al. 2002). Thus, there is a need for larger longitudinal studies to comprehensively characterize this association, including across the overall spectrum of HAND. It would also be of interest to determine how findings from HIV low burden settings compare with results from high burden settings with distinct HIV subtypes.

In this report, we examined the association between levels of plasma HIV RNA and cognitive function, utilizing repeated measures framework, among a cohort in HIV high burden and resource limited setting.

Methods

Study design and participants:

This was a prospective cohort study conducted in Abuja Nigeria between 2011 and 2014. A total of 179 HIV infected participants with available plasma HIV RNA results and followed longitudinally for up to 2 years were included for the analysis in this study.

In the overall cohort, 216 HIV infected and 114 HIV uninfected participants were enrolled consecutively from HIV counseling and testing centers at two tertiary facilities in Abuja, Nigeria, the National Hospital (NHA) and the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital (UATH). All individuals were ≥18 years of age, able to communicate in English and antiretroviral naïve at enrollment, but subsequently initiated on cART as they became eligible based on the Nigerian treatment guidelines. The participants also had no evidence of active central nervous system (CNS) or systemic disease based on clinical assessment that does not include spinal analysis or imaging studies. There was also no history of significant head trauma, current or history of alcohol abuse, use of other mind-altering substances, or evidence of substance use on urine toxicology screening. Prospective participants were also excluded if they had previous diagnosis of a learning disability or psychiatric disorder. Demographic and clinical information were obtained using standardized questionnaires, a thorough general medical assessment as well as a comprehensive neuropsychological testing. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and study procedures were approved by University of Maryland Baltimore, NHA, and UATH Institutional Review Boards.

Follow up Schedule:

Participants were seen at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after their baseline assessment visit. At each of these study visits, the participants had comprehensive neuropsychological assessment as well as clinical evaluation and laboratory tests (plasma HIV RNA, CD4 cell count etc.).

Clinical and Laboratory Assessments

Neuropsychological assessment:

A standardized 22 test neuropsychological battery was administered to all study participants by an examiner blinded to the HIV serological status of the participant. Details of these are described in our other reports (Akolo et al. 2014; Royal et al. 2016; Jumare et al. 2017). Participants were screened for effort using the Hiscock Digit Memory Test, and for depression with the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al. 1996).

Raw test scores from the neuropsychological tests were converted to scaled scores based on the scores of the HIV uninfected controls. Standardized T-scores adjusted for age, gender and education were then generated for each test (with mean of 50 and standard deviation [SD] of 10).

Follow up scores were also adjusted for practice effect, using HIV uninfected individuals as controls for the first follow up visit. HIV infected participants with stable HIV disease during follow up (WHO clinical stage 1, stable CDC stage, and plasma viral load change less than 1 log10) were utilized for this adjustment afterwards, as the HIV uninfected participants were only followed through the second study visit.

Deficit scores (DS) ranging from 0 to 5 (0=no deficit and 5=severe deficit) were created for each test from the T-scores: T-score >40= DS score of 0; T-score 35-39= DS score of 1; T-score 30-34= DS score of 2; T-score 25-29= DS score of 3; T-score 20-24= DS of 4; T-score <20= DS score of 5. The T scores and deficit scores for individual tests were averaged to generate a mean T score and deficit score for each of the 7 domains, and across all tests to calculate a global T score and global deficit score (GDS) respectively. Mean T score below 40 in each domain signified impairment for that domain, while GDS ≥ 0.5 was defined as global neurocognitive impairment (Carey et al. 2004; Blackstone et al. 2012).

Laboratory testing:

Whole blood from participants was used for the determination of HIV-1 serological status, measurement of plasma HIV RNA viral load (VL) and CD4+ T cell count. Plasma HIV-1 RNA quantification (VL) was done using the COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan version 2.0 (Cobas Amplicor; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) with a detection limit of 20 copies/ml. CD4 count was measured using laser-based CD4 T-lymphocyte enumeration (Cyflow SL, Partec, Munster, Germany). All tests were performed at the Institute of Human Virology, Nigeria-supported Training Laboratory located at the Asokoro District Hospital, Abuja.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between participants with and without cognitive impairment using chi-square, Wilcoxon and t tests. Global T scores were compared between participants with low viral load (HIV RNA < 1000 copies/ml) and those with higher levels (HIV RNA ≥ 1000 copies/ml) using t test. Multivariable linear regression models were fit to determine mean change in global and domain T scores per log10 increase in plasma HIV RNA, adjusting for CD4 count, Beck’s depression score, age, gender, years of education, and antiretroviral treatment status. Similarly, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was done to assess the odds of cognitive impairment per log10 increase in plasma HIV RNA, adjusting for the same variables.

Baseline analyses were implemented using generalized linear models, while longitudinal analyses were implemented using generalized estimating equations (GEE) framework with an exchangeable correlation structure. Multivariable conditional logistic regression analysis was also performed to assess within person associations. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The median age of participants at baseline was 34 years, and females constituted about two-thirds of this cohort. Both age and gender did not differ by impairment status. Participants with impairment had a higher median number of years of education when compared to the unimpaired (p=0.012) (Table 1). The median CD4 cell count and hemoglobin were 331.5 cells/mm3 and 12.1 g/dl respectively, and these did not differ by impairment status. Mean plasma HIV RNA was significantly higher among the impaired (p=0.023). The median Beck’s depression score was 6, also not statistically different between impaired and unimpaired participants (Table 1). The proportion of participants initiated on antiretroviral treatment progressively increased from 45.6% at visit 2 to 58.8% by the last study visit. Antiretroviral treatment status did not differ between the impaired and unimpaired. Proportion of participants with missing plasma HIV RNA measurements ranged from 17.1% to 30.2% between visits 1 and 3. Baseline impairment status did not differ between those with and without plasma HIV RNA measurements during those visits. However, there was marginal evidence of a difference for visit 4 when the study was prematurely closed out with around 40% follow up accrual (p=0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| All N=179 | Unimpaired N=134 | Impaired N=45 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), Median (IQR) | 34 (11) | 33.5 (11) | 34 (10) | 0.901W |

| Gender, Female n (%) | 115 (64.3) | 84 (62.7) | 31 (68.9) | 0.453C |

| Education (years), Median (IQR) | 12 (3) | 12 (2) | 13 (4) | 0.012W |

| CD4 cell count/μL, Median (IQR) | 331.5 (256) | 324 (258) | 357 (237) | 0.705W |

| Hemoglobin g/dl, Median (IQR) | 12.1 (2.1) | 12.2 (1.9) | 11.7 (2) | 0.118W |

| Log10 Plasma HIV RNA copies/ml, Mean (SD) | 4.3 (1.07) | 4.19 (1.14) | 4.61 (0.73) | 0.023T |

| Beck’s Depression Score, Median (IQR) | 6 (9) | 5 (9) | 7 (13) | 0.751W |

| Antiretroviral Treatment, n (%) | ||||

| Visit 2 | 78 (45.6) | 55 (43.7) | 23 (51.1) | 0.388C |

| Visit 3 | 87 (54.4) | 59 (53.2) | 28 (57.1) | 0.641C |

| Visit 4 | 50 (58.8) | 31 (59.6) | 19 (57.6) | 0.852C |

| Missing Plasma HIV RNA, n (%) | ||||

| Visit 1 | 37 (17.1) | 25 (15.7) | 12 (21.1) | 0.413C |

| Visit 2 | 54 (30.2) | 39 (29.1) | 15 (33.3) | 0.580C |

| Visit 3 | 50 (27.9) | 36 (26.9) | 14 (31.1) | 0.571C |

| Visit 4 | 111 (62) | 89 (66.4) | 22 (48.9) | 0.05C |

WWilcoxon

CChisquare

Tt test

IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; N: number of participants

Association of Plasma HIV RNA Levels with Global and Domain-Specific Cognitive Performance

Baseline:

In a multivariable linear regression model, adjusting for CD4 cell count, Beck’s depression score, age, gender, and years of education, global T scores decreased by 1.01 per log10 increase in Plasma HIV RNA (lower T score associated with poorer cognition) [95% CI: −1.78, −0.24; p=0.01]. For the individual cognitive domains, there was a similar significant decrease in T scores per log10 increase in plasma HIV RNA for the speed of information processing, executive function, and verbal fluency, as well as a marginally significant decrease for the learning domain. The observed significant decrease in T scores ranged from 1.25 (for executive function) to 1.63 (for verbal fluency), consistent with lower cognitive performance as plasma HIV RNA burden increased (p=0.024 and p=0.005 respectively) [Table 2].

Table 2:

*Multivariable Linear Regression Analyses for Baseline and Longitudinal Association of Global and Domain Cognitive T Scores with Plasma HIV RNA Levels

| ^Baseline | #Longitudinal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | β | 95% CI | p value | β | 95% CI | p value | |

| Global | 179 | −1.01 | −1.78, −0.24 | 0.01 | −0.35 | −0.67, −0.03 | 0.033 |

| Domain | |||||||

| Speed of Information Processing | 179 | −1.62 | −2.88, −0.35 | 0.012 | −0.7 | −1.35, −0.04 | 0.036 |

| Attention/Working Memory | 179 | −0.92 | −2.13, 0.28 | 0.133 | 0.04 | −0.51, 0.59 | 0.891 |

| Executive Function | 179 | −1.25 | −2.34, −0.16 | 0.024 | −0.49 | −1.03, 0.06 | 0.081 |

| Learning | 179 | −0.82 | −1.9, 0.26 | 0.136 | −0.59 | −1.22, 0.04 | 0.067 |

| Memory | 179 | −1.13 | −1.37, 0.11 | 0.074 | −0.41 | −1.05, 0.23 | 0.21 |

| Verbal Fluency | 179 | −1.63 | −2.77, −0.5 | 0.005 | −0.6 | −1.11, −0.1 | 0.019 |

| Motor Speed and Dexterity | 179 | −0.02 | −1.08, 1.04 | 0.971 | −0.18 | −0.66, 0.3 | 0.472 |

Adjusted for CD4 Count, Beck’s depression score, years of education, age, gender, and antiretroviral treatment status

: mean change in t score per unit change in log10 plasma HIV RNA; CI: confidence interval; N: number of participants

Generalized linear model

Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE)

Longitudinal:

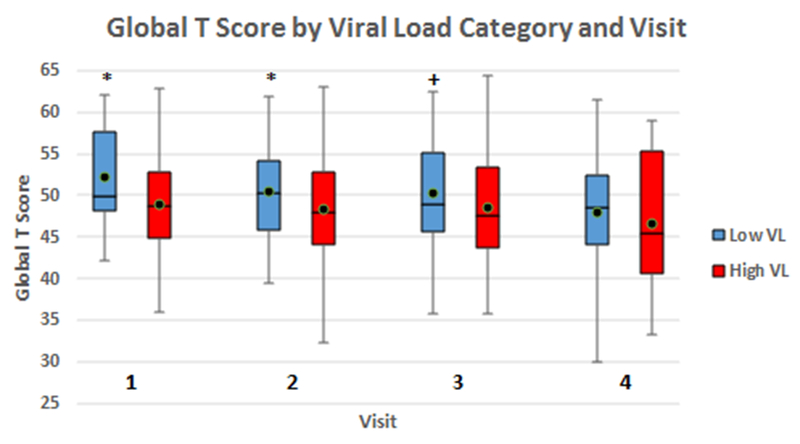

Adjusting for the same variables and antiretroviral treatment status, global T scores decreased by 0.35 per log10 increase in plasma HIV RNA [95% CI: −0.67, −0.03; p=0.033]. There was a similar significant decrease in T scores per log10 increase in plasma HIV RNA for the speed of information processing and verbal fluency domains (mean change: −0.7 and −0.6; P=0.036 and p=0.019), as well as trends towards significant decrease for the executive function and learning domains (p=0.081 and p=0.067) (Table 2). Utilizing a categorical classification for HIV RNA, participants with low viral load (HIV RNA < 1000 copies/ml) had significantly lower global T scores as compared to those with higher VL (Mean difference: −1.01 [95% CI: −1.93, −0.08; p=0.032] (Figure 1).

Fig 1:

Comparisons of global neuropsychological T scores between participants with low plasma viral load (HIV RNA < 1000 copies/ml) and those with higher levels (HIV RNA ≥ 1000 copies/ml) for individual study visits. Overall longitudinal comparison utilizing GEE linear regression analysis framework also yielded statistically significant differences (Mean difference: −1.01 [95% CI: −1.93, −0.08]; p=0.032).

*: p < 0.05 +: p ≥ 0.05 but < 0.1 black dot: mean T score VL: viral load GEE: generalized estimating equations

Association of Plasma HIV RNA Levels with Global and Domain Specific Cognitive Impairment

Baseline:

In a multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for the same variables (as above), the odds of global neurocognitive impairment were 95% higher per log10 increase in plasma HIV RNA (OR: 1.95 [95% CI: 1.19, 3.19]; p=0.008) (Table 3). Adjusting for the same variables, the odds of impairment for the speed of information processing domain was 94% higher per log10 increase in plasma HIV RNA (OR: 1.94 [95% CI: 1.04, 3.61]; p=0.036). Similarly, the odds of impairment for the verbal fluency domain was 2.34 times higher per log10 increase in plasma HIV RNA (OR: 2.34 [95% CI: 1.17, 4.67]; p=0.016). The odds of impairment for the executive function domain showed a trend towards significance (OR: 1.64 [95% CI: 0.93, 2.92]; p=0.09). The pattern of association for the other domains was in a similar direction but not statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3:

*Multivariable Logistic Regression Analyses for Baseline and Longitudinal Association of Global and Domain Cognitive Impairment with Plasma HIV RNA Levels

| ^Baseline | #Longitudinal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Global | 179 | 1.95 | 1.19, 3.19 | 0.008 | 1.28 | 1.08, 1.51 | 0.005 |

| Domain | |||||||

| Speed of Information Processing | 179 | 1.94 | 1.04, 3.61 | 0.036 | 1.37 | 1.08, 1.74 | 0.01 |

| Attention/Working Memory | 179 | 1.48 | 0.81, 2.71 | 0.203 | 1.28 | 1.02, 1.61 | 0.032 |

| Executive Function | 179 | 1.64 | 0.93, 2.92 | 0.09 | 1.28 | 1.01, 1.62 | 0.038 |

| Learning | 179 | 1.13 | 0.65, 1.99 | 0.661 | 1.08 | 0.83, 1.40 | 0.58 |

| Memory | 179 | 1.20 | 0.72, 1.99 | 0.496 | 1.07 | 0.89,1.29 | 0.495 |

| Verbal Fluency | 179 | 2.34 | 1.17, 4.67 | 0.016 | 1.22 | 0.98, 1.53 | 0.082 |

| Motor Speed and Dexterity | 179 | 1.06 | 0.51, 2.19 | 0.873 | 1.10 | 0.83, 1.47 | 0.511 |

Adjusted for CD4 Count, Beck’s depression score, years of education, age, gender, and antiretroviral treatment status

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; N: number of participants

Generalized linear model

Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE)

Longitudinal:

Adjusting for the same variables (as above) in a multivariable logistic regression, the odds of global neurocognitive impairment were 28% higher per log10 increase in plasma HIV RNA (OR: 1.28 [95% CI: 1.08, 1.51]; p=0.005) (Table 3). The odds of impairment were also significantly higher per log10 increase in plasma HIV RNA for the speed of information processing, attention and executive function domains (ORs: 1.37, 1.28, and 1.28; p values: 0.01, 0.032, and 0.038, respectively). The association for the verbal fluency domain showed a trend towards significance (OR: 1.22; p=0.082). In a stratified analysis, the odds of global impairment were significant among treatment naïve (OR: 1.43 [95% CI: 1.1, 1.85]; p=0.007) but not among treatment experienced participants (OR: 1.04 [95% CI: 0.79, 1.36]; p=0.794).

Utilizing conditional logistic regression analysis for within person changes, and adjusting for the same variables, the odds of global neurocognitive impairment were 2.2 times higher per log10 increase in plasma HIV RNA (OR: 2.2 [95% CI: 1.17, 4.17]; p=0.015).

The participants in this study received simple first line antiretroviral regimens with a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) arm (either Nevirapine [NVP] or Efavirenz [EFV]) and a nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (N/NtRTI) arm (either Zidovudine [AZT] or Tenofovir [TDF]). Overall, the sum of the CNS penetration effectiveness (CPE) scores of the individual regimens were similar among the treated participants. However, we compared cognitive performance between NVP versus EFV treated patients (higher versus lower CPE score) as well as between AZT versus TDF treated individuals (high versus low CPE score) and found no significant differences. Data on these were not included because less than 50% of the participants were on antiretroviral treatment during this study (due to the treatment eligibility criteria in Nigeria at that time).

Discussion

In this study, we found a significant association between levels of plasma HIV RNA and neurocognitive performance among treatment naïve patients at baseline, as well as longitudinally during a 2 year follow up in a repeated measures analysis framework.

We also showed, utilizing conditional logistic regression methods, an even stronger association for within person analysis. A valuable strength of such an analytic approach is its intrinsic property to account for some confounding, since individuals essentially serve as their own controls (Connolly and Liang 1988). Beyond consolidating the findings in the repeated measures framework, which incorporates both within and between person associations, it clearly demonstrates that among participants who actually experience changes in cognitive status and plasma HIV RNA levels the correlation is significantly enhanced.

Although we found a significant association longitudinally among a cohort of mixed treatment naïve and experienced individuals, the effect sizes were significantly attenuated when compared to baseline associations that explored exclusively treatment naïve participants. Additionally, the longitudinal findings appear to be driven largely by the baseline associations. In fact, a stratified analysis found no significant association among participants on treatment, but a much stronger association than observed for the combined cohort among those that remained treatment naïve during follow up. The repeated measures analysis framework may have the advantage of relating concurrent levels of exposure and outcome, but may also have a disadvantage, with respect to conditions that are relatively unchanging over time, to merely mirror baseline associations. Nonetheless, it does confer significant advantages over cross-sectional analyses.

The failure to observe significant association among treatment experienced individuals is probably due to the fact that cART has the dramatic effect of lowering plasma HIV RNA to undetectable levels, but only slowly and not always resulting in cognitive improvement. Moreover, the potential neurotoxic adverse effects of cART may mitigate some of its anticipated benefits (Price and Spudich 2008; Cysique et al. 2011; Group 2013). Thus, a likely consequence of cART initiation is to effectively tilt the observed baseline association between plasma HIV RNA and cognitive function towards the null.

Our findings are consistent with other reports. Childs et al. (Childs et al. 1999) reported a significantly higher hazard of dementia among patients with baseline plasma HIV RNA above 3000 copies/ml when compared to those with lower levels, during a 10 year follow up in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). In another longitudinal study from San Diego, Marcotte and colleagues (Marcotte et al. 2003) found a six fold higher risk of cognitive impairment among participants with baseline plasma HIV RNA above 4.5 log10 copies/ml when compared to those with lower levels. Baseline plasma HIV RNA in that study was measured at a median interval of 1 year after seroconversion, and incident cognitive impairment was identified during a median follow up period of 3.2 years. While Childs et al. (Childs et al. 1999) only explored the association of plasma HIV RNA with the severest form of HAND, Marcotte et al. (Marcotte et al. 2003), similar to ours, looked at correlations with the broad HAND spectrum. Looking at associations with milder forms of HAND or the broader spectrum is particularly relevant in this era of widespread use of cART, because of the remarkable decline in the incidence of HAD. Our study differs from both studies by assessing correlations of concurrent plasma HIV RNA and cognitive function. This may confer the unique advantage of potentially accounting for the anticipated longitudinal changes in HIV RNA and cognitive performance following the introduction of cART. Beside these longitudinal studies, Ferrando and colleagues, (Ferrando et al. 1998) in a cross-sectional study of 130 mixed treatment naïve and experienced men, found significantly higher mean plasma HIV RNA level among neuro-psychologically impaired patients when compared to the unimpaired in univariable analysis. Similarly, they also showed a lower proportion of participants with undetectable plasma HIV RNA among the impaired (Ferrando et al. 1998).

A number of other studies failed to demonstrate a significant association between plasma HIV RNA and cognitive function. In a cross-sectional study, Reger et al. (Reger et al. 2005) found no significant correlation between plasma HIV RNA categories and performance (scores) within cognitive domains among 140 treatment experienced patients. However, this study did not assess relationships with either individual domain or global cognitive impairment. In contrast, another cross-sectional study among 30 participants, mostly treatment experienced, found a significant correlation with performance in tests of psychomotor speed (r=−0.47; P-value= 0.041), but no such association with the global cognitive function (Stankoff et al. 1999). Similarly, in relatively small cross-sectional studies with mixed treatment-naïve and experienced participants, Ellis et al. (Ellis et al. 1997) and Robertson et al. (Robertson et al. 1998) reported a significant association between neurocognitive dysfunction and CSF HIV RNA, but not plasma HIV RNA levels. McArthur et al. (McArthur et al. 1997), in a much larger cross-sectional study (N=207), also showed similar findings. Furthermore, Ellis and colleagues in a longitudinal study of 134 mixed treatment naïve and experienced patients, demonstrated a strong association between baseline HIV RNA levels within the CSF and incidence of cognitive impairment or declining cognitive performance, but only a weak trend (P-value= 0.08) for the association with plasma HIV RNA (Ellis et al. 2002).

Overall, these studies show that levels of HIV RNA in both CSF and plasma prior to the initiation of cART, especially in the early stages of infection, may have significant predictive value for later occurrence of cognitive dysfunction. The increased risk for cognitive impairment may possibly be related to the level of patients’ viral set point, known to be established soon after infection, and predictive of the clinical course of HIV disease and its sequelae (Henrard et al. 1995; Huang et al. 2012). High plasma HIV RNA during acute HIV infection is associated with viral seeding into the CNS mainly through trafficking within mononuclear cells across the blood brain barrier (Spudich and González-Scarano 2012). Such early neuro-invasion may result in neuropathic effects and possible establishment of a CNS reservoir (Spudich 2013). It is not known to what extent this early seeding of virus in the CNS leads to later development of cognitive dysfunction. However, it is likely that both ‘autonomous’ infection within the CNS compartment progressing from early seeded virus, and ‘transitory’ infection from recurrent seeding into the CNS throughout the course of chronic HIV disease, contribute to the pathogenesis of HAND (Rausch and Davis 2001; Zayyad and Spudich 2015). Early irreversible damage to the CNS, a legacy event, is thought to be partly responsible for the persistence of HAND in this era of cART (Brew and Chan 2014).

With a unique study population, infected with different HIV strains in a resource limited and high burden setting, our findings essentially buttress the apparent consensus that plasma HIV RNA is not a strong predictor of cognitive dysfunction during antiretroviral treatment. On the contrary, It is generally agreed that CSF HIV RNA has a much stronger predictive value for HAND in the era of cART, although this is also attenuated when compared to findings among pretreatment patients (Nath et al. 2008). The difference between plasma and CSF findings may be partly due to an apparent lag in response to cART by virus within the CSF, particularly for drugs with poor CNS penetration effectiveness (CPE). It may also be due to CNS viral escape and compartmentalization, resulting in ‘autonomous’ CNS infection despite systemic viral suppression.

The global associations we found in this study are largely driven by impairments in the speed of information processing, executive function, and verbal fluency cognitive ability domains. These are among the most frequently affected domains in HIV/AIDS, (Reger et al. 2002; Woods et al. 2009) thereby providing some empiric evidence in support of our results.

The findings in this study, similar to others alike, may have significant implications for treatment, care and prevention. There is a glaring need to intensify the implementation of strategies that foster early initiation of cART, retention in care and optimal adherence. Accordingly, the World Health Organization’s ‘test and treat’ policy recommendation (Camlin et al. 2016) may be invaluable towards ameliorating the burden of HAND (Sanford et al. 2018). This could be of paramount importance especially in resource constrained settings, where late presentation and limited access to treatment remain formidable challenges.

This study has some limitations. About 30% of participants were lost to follow up, and an even higher proportion had missing assessment at the last visit due to premature study close-out. However, those lost did not differ significantly from those retained by baseline impairment status or key clinical and demographic characteristics. Therefore, this was unlikely to have introduced significant selection bias. Another limitation is the Lack of imaging studies for our participants, since occult CNS conditions undetectable by clinical neurological examination may confound our findings.

Among key strengths in this study is the substantially larger sample size available when compared to similar studies, resulting in increased power. Moreover, the repeated measures analysis framework utilized provided estimates for concurrent associations, potentially addressing the fluctuating nature of HAND with or without treatment, in addition to boosting the power of the study even further. To our knowledge, this is the first study from sub-Saharan Africa that comprehensively explored the association between plasma HIV RNA and cognitive performance, providing complementary evidence in support of earlier findings from other settings with different disease burden and HIV-1 subtypes.

Conclusion

In this study, we found a significant association between plasma HIV RNA levels and cognitive function in both baseline cross-sectional and repeated measures longitudinal analyses. Consistent with other reports, our findings appear to be driven by the strong association existing among antiretroviral treatment naïve participants. This lends further support to the widely accepted proposition that while plasma HIV RNA is a valuable predictor of HAND among pretreatment patients, it may not be so in those already on cART. Therefore, studies are needed to identify other viral characteristics with strong predictive value for HAND among treatment experienced patients.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant #R01 MH086356 (to William A. Blattner and Walter Royal, III) and by National Institutes of Health Fogarty/AIDS International Training and Research Program grant #2D43TW001041-14 (training support to Jibreel Jumare).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report

This work was presented in part at the 19th Annual International Meeting of the Institute of Human Virology, 23rd-26th October 2017, Baltimore, Maryland, USA (Abstract P-D6).

References

- Akolo C, Royal W III, Cherner M, Okwuasaba K, Eyzaguirre L, Adebiyi R, Umlauf A, Hendrix T, Johnson J, Abimiku A e ,Blattner W (2014). “Neurocognitive impairment associated with predominantly early stage HIV infection in Abuja, Nigeria.” Journal of neurovirology 20(4): 380–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V ,Wojna VE (2007). “Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.” Neurology 69(18): 1789–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA ,Brown GK (1996). Beck Depression Inventory San Antonio, TX, Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone K, Moore DJ, Franklin DR, Clifford DB, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, Ellis RJ, Atkinson JH, Grant I ,Heaton RK (2012). “Defining neurocognitive impairment in HIV: deficit scores versus clinical ratings.” Clin Neuropsychol 26(6): 894–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brew BJ ,Chan P (2014). “Update on HIV dementia and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.” Current neurology and neuroscience reports 14(8): 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camlin CS, Seeley J, Viljoen L, Vernooij E, Simwinga M, Reynolds L, Reis R, Plank R, Orne-Gliemann J, McGrath N, Larmarange J, Hoddinott G, Getahun M, Charlebois ED ,Bond V (2016). “Strengthening universal HIV ‘test-and-treat’ approaches with social science research.” AIDS (London, England) 30(6): 969–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey CL, Woods SP, Gonzalez R, Conover E, Marcotte TD, Grant I ,Heaton RK (2004). “Predictive validity of global deficit scores in detecting neuropsychological impairment in HIV infection.” J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 26(3): 307–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs EA, Lyles RH, Selnes OA, Chen B, Miller EN, Cohen BA, Becker JT, Mellors J ,McArthur JC (1999). “Plasma viral load and CD4 lymphocytes predict HIV-associated dementia and sensory neuropathy.” Neurology 52(3): 607–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly MA ,Liang K-Y (1988). “Conditional Logistic Regression Models for Correlated Binary Data.” Biometrika 75(3): 501–506. [Google Scholar]

- Cysique LA, Waters EK ,Brew BJ (2011). “Central nervous system antiretroviral efficacy in HIV infection: a qualitative and quantitative review and implications for future research.” BMC Neurology 11(1): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Hsia K, Spector SA, Nelson JA, Heaton RK, Wallace MR, Abramson I, Atkinson JH, Grant I ,McCutchan JA (1997). “Cerebrospinal fluid human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA levels are elevated in neurocognitively impaired individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center Group.” Annals of neurology 42(5): 679–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Moore DJ, Childers ME ,et al. (2002). “PRogression to neuropsychological impairment in human immunodeficiency virus infection predicted by elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of human immunodeficiency virus rna.” Archives of Neurology 59(6): 923–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando S, van Gorp W, McElhiney M, Goggin K, Sewell M ,Rabkin J (1998). “Highly active antiretroviral treatment in HIV infection: benefits for neuropsychological function.” AIDS 12(8): F65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Scarano F ,Martin-Garcia J (2005). “The neuropathogenesis of AIDS.” Nat Rev Immunol 5(1): 69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group T M E W (2013). “Assessment, Diagnosis, and Treatment of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder: A Consensus Report of the Mind Exchange Program.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 56(7): 1004–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR Jr., Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, Vigil OR, Taylor MJ, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J ,Grant I (2010). “HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study.” Neurology 75(23): 2087–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Letendre SL, Leblanc S, Corkran SH, Duarte NA, Clifford DB, Woods SP, Collier AC, Marra CM, Morgello S, Mindt MR, Taylor MJ, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Wolfson T, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Simpson DM, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J ,Grant I (2011). “HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors.” Journal of neurovirology 17(1): 3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrard DR, Phillips JF, Muenz LR, Blattner WA, Wiesner D, Eyster ME ,Goedert JJ (1995). “Natural history of HIV-1 cell-free viremia.” Jama 274(7): 554–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Chen H, Li W, Li H, Jin X, Perelson AS, Fox Z, Zhang T, Xu X ,Wu H (2012). “Precise determination of time to reach viral load set point after acute HIV-1 infection.” Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes 61(4): 448–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumare J, Sunshine S, Ahmed H, El-Kamary SS, Magder L, Hungerford L, Burdo T, Eyzaguirre LM, Umlauf A, Cherner M, Abimiku A, Charurat M, Li JZ, Blattner WA ,Royal W 3rd (2017). “Peripheral blood lymphocyte HIV DNA levels correlate with HIV associated neurocognitive disorders in Nigeria.” Journal of neurovirology 27(10): 017–0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte TD, Deutsch R, McCutchan J ,et al. (2003). “Prediction of Incident Neurocognitive Impairment by pPasma HIV RNA and CD4 Levels Early after HIV Seroconversion.” Archives of Neurology 60(10): 1406–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur JC, McClernon DR, Cronin MF, Nance-Sproson TE, Saah AJ, St Clair M ,Lanier ER (1997). “Relationship between human immunodeficiency virus—associated dementia and viral load in cerebrospinal fluid and brain.” Annals of neurology 42(5): 689–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellors JW, Rinaldo CR Jr., Gupta P, White RM, Todd JA ,Kingsley LA (1996). “Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma.” Science 272(5265): 1167–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath A, Schiess N, Venkatesan A, Rumbaugh J, Sacktor N ,McArthur J (2008). “Evolution of HIV dementia with HIV infection.” Int Rev Psychiatry 20(1): 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RW ,Spudich S (2008). “Antiretroviral therapy and central nervous system HIV type 1 infection.” J Infect Dis 15(197): 533419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VR, Ruiz AP ,Prasad VR (2014). “Viral and cellular factors underlying neuropathogenesis in HIV associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND).” AIDS research and therapy 11: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch DM ,Davis MR (2001). “HIV in the CNS: Pathogenic relationships to systemic HIV disease and other CNS diseases.” Journal of neurovirology 7(2): 85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger M, Welsh R, Razani J, Martin DJ ,Boone KB (2002). “A meta-analysis of the neuropsychological sequelae of HIV infection.” J Int Neuropsychol Soc 8(3): 410–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger MA, Martin DJ, Cole SL ,Strauss G (2005). “The relationship between plasma viral load and neuropsychological functioning in HIV-1 infection.” Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 20(2): 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson K, Fiscus S, Kapoor C, Robertson W, Schneider G, Shepard R, Howe L, Silva S ,Hall C (1998). “CSF, plasma viral load and HIV associated dementia.” Journal of neurovirology 4(1): 90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal W 3rd, Cherner M, Burdo TH, Umlauf A, Letendre SL, Jumare J, Abimiku A, Alabi P, Alkali N, Bwala S, Okwuasaba K, Eyzaguirre LM, Akolo C, Guo M, Williams KC ,Blattner WA (2016). “Associations between Cognition, Gender and Monocyte Activation among HIV Infected Individuals in Nigeria.” PloS one 11(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford R, Fellows LK, Ances BM ,Collins D (2018). “Association of brain structure changes and cognitive function with combination antiretroviral therapy in hiv-positive individuals.” JAMA Neurology 75(1): 72–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spudich S (2013). “HIV and Neurocognitive Dysfunction.” Current HIV/AIDS reports 10(3): 235–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spudich S ,González-Scarano F (2012). “HIV-1-Related Central Nervous System Disease: Current Issues in Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment.” Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 2(6): a007120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankoff B, Calvez V, Suarez S, Bossi P, Rosenblum O, Conquy L, Turell E, Dubard T, Coutellier A, Baril L, Bricaire F, Lacomblez L ,Lubetzki C (1999). “Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) RNA levels in HIV-related cognitive impairment.” Eur J Neurol 6(6): 669–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Moore DJ, Weber E ,Grant I (2009). “Cognitive Neuropsychology of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders.” Neuropsychology Review 19(2): 152–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayyad Z ,Spudich S (2015). “Neuropathogenesis of HIV: From Initial Neuroinvasion to HIV Associated Neurocognitive Disorder (HAND).” Current HIV/AIDS reports 12(1): 16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]