Abstract

The emergence of biologic therapies is arguably the greatest therapeutic advance in the care of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) to date, allowing directed treatments targeted at highly specific molecules shown to play critical roles in disease pathogenesis, with advantages in potency and selectivity. Furthermore, a large number of new biologic and small-molecule therapies in IBD targeting a variety of pathways are at various stages of development that should soon lead to a dramatic expansion in our therapeutic armamentarium. Additionally, since the initial introduction of biologics, there have been substantial advances in our understanding as to how biologics work, the practical realities of their administration, and how to enhance their efficacy and safety in the clinical setting. In this review, we will summarize the current state of the art for biological therapies in IBD, both in terms of agents available and their optimal use, as well as preview future advances in biologics and highly targeted small molecules in the IBD field.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) incorporates a spectrum of chronic, often progressive and disabling, inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Though the exact etiology remains elusive, it is generally accepted that they result from a multifactorial process involving stimulation of a dysfunctional immune system by an environmental trigger, most likely luminal microbiota and their associated antigens and adjuvants, in a genetically predisposed individual.1–3 While there is growing interest in targeting different factors of this process, such as the gastrointestinal microbiota, the overwhelming majority of therapies in IBD target and ameliorate the dysfunctional immunological response.4–6

The most potent of such therapies are the biologics, and their emergence roughly 20 years ago7 revolutionized the treatment of chronic inflammatory disorders, including IBD. Biologic agents are medicinal products derived from a natural source and include large, protein-based therapeutic agents typically obtained from living cell lines using recombinant DNA technology such as monoclonal antibodies.8 Such agents invariably specifically target critical mediators in key immunological and inflammatory pathways, allowing selective but highly potent regulation.

CURRENTLY AVAILABLE THERAPIES

Anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) agents

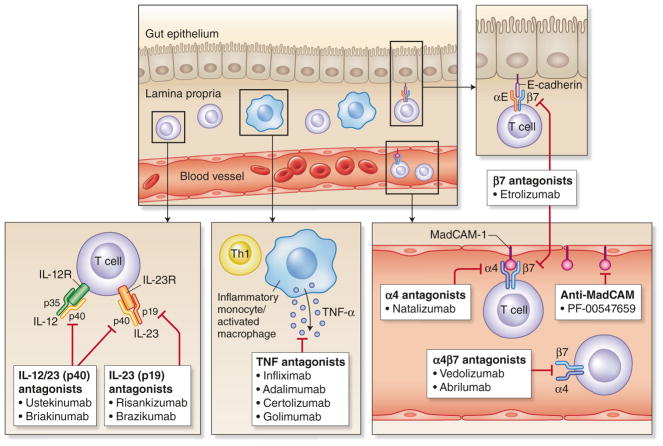

The first class of biologic agents investigated and then approved for use in IBD is the anti-TNF-α agents, which inhibit the cytokine TNF-α which is central in the mediation of systemic inflammation (Fig. 1). This class of biologics, characterized by a relatively quick onset of action, is highly effective in both the gastrointestinal9,10 and extra-intestinal11 manifestations of disease, and remains the most widely used biologic class in the treatment of IBD. Initial concerns regarding the safety of these agents have decreased with accumulating data. Although there is a slightly increased risk of serious infections, this is lower than initially predicted and less than the risk associated with steroid use.12 Concerns regarding increased likelihood of malignancy and lymphoma13–15 also appear to be overstated, especially relative to the risk of existing immunomodulator therapies. Other adverse events, such as immune-mediated infusion reactions, skin lesions, arthritis, and demyelinating disorders, can occur but are usually either self-limiting on therapy cessation or relatively rare. Four different anti-TNF-α agents are approved for use in IBD to date.

Fig. 1. Mechanism of action of existing and investigational biologic agents in IBD.

TNF tumor necrosis factor, Th1 T helper cell 1, MAdCAM-1 mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule 1

Infliximab

In 1997, the first multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind investigation into the success of an anti-TNF-α antibody, infliximab, in Crohn’s disease was published,16 having earlier been the first drug demonstrating the ability to induce endoscopic healing.17 Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody, approved for use in both CD18,19 and UC20 (Tables 1 and 2), administered as an intravenous infusion with a weight-based dosage (standard 5 mg/kg).

Table 1.

Summary of key registration trial efficacy data for approved biologics in Crohn’s disease

| Biologic | Clinical remission or response | Mucosal healing |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-TNF-α | ||

| Infliximab | Induction: 81% vs 17% clinical response week 4 [Targan et al.]16 Maintenance: 39% vs 21% clinical remission week 30 [ACCENT I]18 Fistulizing: 36% vs 19% complete fistula closure at week 54 [ACCENT II]19 |

43.9% IFX + AZA combination vs 30.1% IFX monotherapy vs 16.5% AZA monotherapy week 26 [SONIC]104 |

| Adalimumab | Induction: 36% vs 12% clinical remission, 59% vs 37% clinical response week 4 [CLASSIC I]21 Maintenance: 40% vs 17% clinical remission week 26, 36% vs 12% clinical remission week 56 [CHARM]22 Fistulizing (subgroup analysis): 30% vs 13% fistula closure week 26, 33% vs 13% fistula closure week 56 [CHARM]22 |

27% vs 13% week 12 [EXTEND]23 24% vs 0% week 52 [EXTEND]23 |

| Certolizumab | Induction: 37% vs 26% clinical response week 6 [PRECISE I]25 Maintenance: 62% vs 34% clinical response, 48% vs 29% clinical remission week 26 [PRECISE II]26 Fistulizing (subgroup analysis): 36% vs 17% fistula closure week 26 [PRECISE II]28 |

27% endoscopic remission (CDEIS <6), 8% mucosal healing with no ulcers week 54 [MUSIC]27 |

| Anti-integrin | ||

| Natalizumab | Induction: 51% vs 37% clinical response week 4, 26% vs 16% clinical remission week 12 [ENCORE]44 Maintenance: 61% vs 28% clinical response, 44% vs 26% clinical remission week 36 [ENACT II]45 |

|

| Vedolizumab | Induction: Clinical remission 14.5% vs 6.8%, clinical response 31.4% vs 25.7% (NS) week 6 [GEMINI II]52 Maintenance: Clinical remission 39% vs 21.6% week 52 [GEMINI II]52 |

|

| Anti-IL-12/23 | ||

| Ustekinumab | Induction: Clinical response 33.7% vs 21.5% [UNITI-1; anti-TNF non-responder] 55.5% vs 28.7% [UNITI -2] week 6. Clinical remission 18.5% vs 8.9% [UNITI-1; anti-TNF non-responder] 34.9% vs 17.7% [UNITI -2] week 655 Maintenance: Clinical remission 53.1% vs 35.9%, clinical response 59.4% vs 44.3% week 44 [IM-UNITI]55 |

|

Note: The above-listed trials differ in patient selection criteria, prior exposure to other biologic therapies, and study end points

Table 2.

Summary of key registration trial efficacy data for approved biologics in ulcerative colitis

| Biologic | Clinical remission or response | Mucosal healing |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-TNF-α | ||

| Infliximab | Induction: Clinical response 69.4% vs 37.2% [ACT I] and 64.5% vs 29.3% [ACT II] week 8. Clinical remission 38.8% vs 14.9% [ACT I] and 33.9% vs 5.7% [ACT II] week 820 Maintenance: Sustained clinical response 38.8% vs 14% weeks 8/30/54. Sustained clinical remission 19.8% vs 6.6% weeks 8/30/54 [ACT I]20 |

62% vs 33.9% [ACT I], 60.3% vs 30.9% [ACT II] week 820 45.5% vs 18.2% week 54 [ACT I]20 |

| Adalimumab | Induction: Clinical remission 16.5% vs 9.3%, clinical response 50.4% vs 34.6% week 8 [ULTRA-2]24 Maintenance: Clinical remission 17.3% vs 8.5%, clinical response 30.2% vs 18.3% week 52 [ULTRA-2]24 |

41.1% vs 31.7% week 8 [ULTRA-2]24 25% vs 15.4% week 52 [ULTRA-2]24 |

| Golimumab | Induction: Clinical response 51% vs 30.3%, clinical remission 17.8% vs 6.4% week 6 [PURSUIT-SC]29 Maintenance: Clinical response 49.7% vs 31.2%, clinical remission 27.8% vs 15.6% week 54 [PURSUIT-M]30 |

42.3% vs 28.7% week 6 [PURSUIT-SC]29 42.4% vs 26.6% at weeks 30 and 54 [PURSUIT-M]30 |

| Anti-integrin | ||

| Vedolizumab | Induction: Clinical response 47.1% vs 25.5%, clinical remission 16.9% vs 5.4%, week 6 [GEMINI I]51 Maintenance: Clinical remission 41.8% vs 15.9%, clinical response 56.6% vs 23.8% week 52 [GEMINI I]51 |

40.9% vs 24.8% week 6 [GEMINI I]51 51.6% vs 19.8% week 52 [GEMINI I]51 |

Note: The above-listed trials differ in patient selection criteria, prior exposure to other biologic therapies, and study end points

Adalimumab

Adalimumab is a human IgG1 monoclonal anti-TNF-α antibody approved for use in both CD21–23 and UC24 (Tables 1 and 2). In contrast to infliximab, it is administered subcutaneously every 2 weeks at a fixed dose regardless of body weight (standard maintenance dose 40 mg).

Certolizumab pegol

Certolizumab pegol is a humanized pegylated Fab’ fragment of an antibody directed against TNF-α approved for use in CD only25–28 (Table 1). Like adalimumab, it is administered subcutaneously at a fixed dose (standard dose 400 mg). However, unlike adalimumab, standard maintenance dosing is only every 4 weeks (rather than every 2 weeks for adalimumab).

Golimumab

Golimumab is a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed against TNF-α approved for use in UC only29,30 (Table 2), also administered subcutaneously at a fixed dose (standard maintenance dose 100 mg every 4 weeks).

Despite their widespread use and unique therapeutic success, precise mechanisms by which anti-TNF-α drugs induce clinical and mucosal healing remain elusive. Neutralization of TNF by monoclonal antibodies has been proposed as the primary mechanism by which these drugs exert anti-inflammatory effects in IBD. However, the failure in IBD of etanercept, a fusion protein of the extracellular-binding region of the TNF receptor TNF-RII and human IgG1 Fc region, that neutralizes soluble TNF (sTNF) and is efficacious in rheumatoid arthritis,31 indicates a more complex mechanism in resolution of inflammation in IBD. Various in vitro assays measuring the ability of etanercept to bind membrane TNF (mTNF) show varying affinities: comparable to infliximab or adalimumab in cell lines but undetectable in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and lamina propria cells, potentially indicating a role for mTNF and downstream immunomodulation as an explanation for etanercept’s lack of efficacy in IBD.32 Further support for the importance of mTNF over soluble TNF comes from mouse models of IBD.33 Binding of anti-TNFs to mTNF may also activate an outside-to-inside signaling pathway, where mTNF serves as a cellular receptor. In an experiment of infliximab administration in TNF-α-converting enzyme (TACE)-resistant TNF cell lines (where only mTNF is expressed), it was found that apoptosis was dependent on the presence of serine residues in the intracellular portion of mTNF, supporting the hypothesis of outside-to-inside signaling.34

Another significant mechanism of action may be through apoptosis of inflammatory immune cells. Leukocyte apoptosis has been detected after comparing endoscopic data before and after infliximab infusion and observing induction of TUNEL+ cells, mostly CD3+ T cells, indicative of apoptotic activity.35 Evidence exists that infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab can cause antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC).36 In vitro examination of cells overexpressing mTNF has demonstrated that infliximab and adalimumab induce CDC and ADCC but both processes are reduced upon etanercept administration, which is unable to bind C3, and abrogated under certolizumab pegol administration, which does not have an Fc portion.37 The efficacy of certolizumab in treatment despite its inability to cause apoptosis calls into question the significance of apoptosis in anti-TNF treatment of IBD, though this is still up for debate.

Anti-integrin agents

The second class of biologic agents that has proven effective in IBD are the anti-integrin agents. Instead of blocking the production of inflammatory cytokines, this class of agents works by interfering with leukocyte migration to sites of inflammation. They do this by blocking integrins, which are transmembrane receptors present on a variety of cells that mediate cell adhesion, signaling, and migration38,39 (Fig. 1). The α4 integrins present on leukocytes interact with cell adhesion molecules on the vascular endothelium, in particular VCAM-1 and MAdCAM-1, to allow migration of these cells to sites of inflammation.40 The expression of such adhesion molecules is upregulated in response to a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and the adhesion molecules expressed by the vascular endothelium in inflamed gastrointestinal tissues have particular affinity for activated α4 integrins. These integrins need to undergo conformational change of their extracellular domains in response to leukocyte intracellular signaling (inside–out signaling) to activate their adhesive function.41 By inhibiting this interaction between the α4 integrins and cell adhesion molecules, anti-integrins block the migration of inflammatory cells to disease sites, including the gastrointestinal tract, and prevent further perpetuation of the inflammatory cascade. As these agents work by inhibiting leukocyte migration rather than directly blocking inflammatory cytokine mediators, they are slower in onset than the anti-TNF class, but typically result in stable durable maintenance of remission in responders.

Natalizumab

Natalizumab, a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody (IgG4) directed against the alpha-4 subunit of integrin molecules, was the first agent in class for anti-integrins, non-specifically blocking the α4 integrins, both α4β1 and α4β7. This includes blockade of α4 integrins expressed on cells migrating to both the central nervous system through interaction between α4β1 and VCAM-1, and the GI tract through interaction between α4β7 and MAdCAM-1.42 Because of this indiscriminate blockade, natalizumab has proven to be an effective therapy in multiple sclerosis43 as well as Crohn’s disease44,45 (Table 1), administered as an intravenous infusion at a fixed dose regardless of body weight (standard dose 300 mg every 4 weeks). However, enthusiasm for natalizumab was quickly diminished by reports of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), an often fatal demyelinating neurologic condition caused by the opportunistic infection from reactivation of the JC virus. This condition was previously limited to severely immunocompromised individuals, such as those with AIDS, but is predisposed to by natalizumab due to impaired neurologic immunosurveillance resulting from CNS integrin blockade of T cell homing.46,47 This resulted in the medication being temporarily pulled from the market before being FDA approved with a black box warning.48 While still approved for the treatment of Crohn’s disease, regular monitoring for JC virus positivity is recommended and its use has substantially decreased, though it remains a potent therapy for refractory disease.49

Vedolizumab

Vedolizumab is another anti-integrin, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody, but unlike natalizumab, it specifically targets and blocks α4β7 that is found primarily on cells localizing to the GI tract and biliary system through interaction with MAdCAM-1, and not to the CNS.50 It is thus promoted as being gut specific and was the first biologic designed exclusively for IBD. The safety issues related to PML associated with natalizumab are avoided as it does not affect CNS leukocyte trafficking. Vedolizumab is approved for both UC51 and CD52 (Tables 1 and 2), though its efficacy is arguably greater for UC than CD.53 It is administered as an intravenous infusion at a fixed dose regardless of body weight (standard dose 300 mg). Vedolizumab has an excellent safety profile, confirmed on long-term follow-up, due its gut specificity,54 with minimal adverse events asides nasopharyngitis and sinusitis.

Anti-IL-12/23 p40 subunit agents

The most recent class of biologics available for use in IBD is the anti-IL-12/23 class that inhibits the shared p40 subunit (Fig. 1).

Ustekinumab

Ustekinumab is a human IgG antibody developed to bind the p40 protein subunit found in cytokines IL-12 and IL-23. It is currently the only agent in this class available, approved for the treatment of CD55 (Table 1), with studies in UC ongoing at present. It is administered as a fixed-dose (90 mg) subcutaneous injection every 8 weeks after an initial weight-based IV infusion. Outcomes were worse with ustekinumab in anti-TNF-α primary or secondary non-responders (UNITI-1) compared to those who had not failed anti-TNF-α treatment (UNITI-2). Currently available trial data in CD55 along with longer-term registry data in psoriasis patients (for which it is also approved) suggest a favorable side effect profile relative to the anti-TNF-α agents.56,57

The therapeutic benefit of ustekinumab is now believed to be primarily due to IL-23 rather than IL-12 blockade.58 IL-12 activates STAT4, a necessary transcription factor in the long-term induction of a Th1 response.59 Overexpression of IL-12 is observed in Crohn’s disease and other human inflammatory conditions,60,61 but genetic ablation of the IL-12p35 subunit exhibited no protective effect in a mouse model of brain inflammation62 and even a deleterious response in a mouse model of arthritis.63 Conversely, GWAS data found a highly significant association between Crohn’s disease and the IL-23R gene,64 and findings have shown that IL-23 plays a vital role in Th17 responses and in inflammatory bowel disease. For example, IL-23 plays a key role in the proliferation and stabilization of Th17 cells in the gut. Naive T cells show little response to IL-2365; however, in mouse studies, after contact with IL-6 and TGF-β, T cells express the transcription factor RORγT, which, in turn, upregulates expression of IL-23R and allows for maintenance of the Th17 response.66

However, as detailed later, despite the close relationship between IL-23 and the Th17 response, blockade of IL-17 has been reported to exacerbate established IBD. IL-23 blockade as opposed to blockade of downstream mediators, such as IL-17, has specific therapeutic advantages in IBD, including the ability to modulate the gene expression and pathogenicity of Th cell subsets including Th17 cells.58,67–71 IL-23 also has broad effects on other pro-inflammatory cytokines and cell types. In the T cell transfer model of colitis, transfer of IL-23R− /− T cells leads to reduced T cell infiltration into the colon and changes the equilibrium of Th17 and FoxP3+ T regulatory cells, which is associated with attenuation of intestinal inflammation, down-regulation of IL-21 and IL-22 levels, and upregulation of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.72 IL-22 has been characterized as both protective and pathogenic73; for example, transfer of IL-22− /− CD4+ T cells into an IL-22-deficient Rag1− /− host led to more severe colitis than transfer of wild-type CD4+ T cells, demonstrating a protective effect of IL-22.74 IL-23 is also reported to stimulate IL-17 and IFN-γ producing innate lymphoid cells, which aggregate in the inflamed colon of the H. hepaticus mouse model of colitis and show evidence for driving the inflammatory response.68 As will be discussed later, new monoclonal antibodies that specifically bind IL-23p19 and neutralize IL-23 only are in development and also have efficacy in IBD.

Biosimilars

Biologic agents are distinct from conventional medications due to the complexity of their manufacturing process using cell lines and associated protein-based chemical structure, which is then subject to imprecisely defined posttranslational modification. As such, they cannot be identically replicated. This has led to some unique issues when the first of these agents came off patent. It is not possible to create “generics” of biologic agents in the sense that one can for conventional medications. As such, the term biosimilar is used when referring to medications attempting to replicate off-patent originator biologics.75 There is a requirement to prove that they are highly similar to the originator biologic with no clinically meaningful difference in purity, safety, and effectiveness, and to demonstrate comparable efficacy in a clinical trial for a single indication that can then subsequently be extrapolated to other conditions including UC and CD.76 It is also important to distinguish biosimilars from next-generation biologic agents (e.g., adalimumab and golimumab), which though aimed toward the same molecular target as first-generation agents (e.g., infliximab), are chemically different, independently developed, and do not rely upon demonstration of biosimilarity with an originator product for abbreviated approval.77

Although biosimilars of originator infliximab have been available for several years in Europe and Asia, they have only appeared on the US market recently. There were initial concerns regarding the efficacy and safety of these agents, both in the de novo setting and in the context of switching from originator, given the absence of IBD disease-specific-controlled trials.78 Multiple prospective cohort studies have largely reassured treating gastro-enterologists about the use of biosimilars in the treatment-naive patient.79,80 However, some concerns remain regarding switching from originator biologic to biosimilar, and even more so regarding multiple switches including from one biosimilar to another different biosimilar. While the multi-condition Norwegian NORS-WITCH trial showed no difference across all indications in this non-inferiority study assessing diseases worsening, there was a potential signal in the CD cohort (21.2% disease worsening with originator vs 36.5% with biosimilar CT-P13).81

POSITIONING OF CURRENTLY AVAILABLE BIOLOGIC THERAPIES IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Given the absence of direct head–head comparative efficacy and safety trials between the various biologic agents currently available, relative selection and positioning of biologic treatments are often influenced by both patient-specific factors and financial considerations.

The anti-TNF agents are the most commonly utilized first-line biologics. This is because they have been available the longest and thus are the most widely accessible, have the greatest supporting evidence base in terms of associated patient-years’ experience, physician familiarity, and also the fact they are generally the least expensive. Some insurance policies in the United States require failure of or contraindication to anti-TNF agents before approving other biologic classes. Anti-TNF agents remain the first-line choice for perianal fistulizing CD19 and acute severe colitis,82 as to date there is only randomized controlled trial evidence supporting the use of infliximab for such indications. The anti-TNF agents also have the most evidence supporting their use in the treatment of the multitude of extra-intestinal manifestations (including articular, ocular, and dermatologic) of IBD.11 While there have not been direct comparative trials between the various anti-TNF agents, infliximab with its intravenous route of administration, weight-based dosing, ease in flexibility of dosing, and speed of onset is often the preferred choice in severe disease and hospitalized patients. There is a concern that the subcutaneous anti-TNF agents (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol in CD, and golimumab in UC) that are not weight based may in fact be underdosed in a significant proportion of patients, especially in ulcerative colitis, and there are in fact trials currently underway reexamining the efficacy of higher-dose adalimumab therapy (SERENE UC—NCT02065622 and SERENE CD—NCT02065570). In contrast, the subcutaneous anti-TNF agents are often preferred in patients who place importance on the convenience, autonomy, and flexibility of their biologic therapy, given that these agents are self-administered.

In terms of the anti-integrin therapies, while natalizumab use has greatly diminished due to concerns regarding PML, the distinguishing feature of vedolizumab relative to the anti-TNF agents is its excellent safety profile attributable to its gut selectivity and resultant avoidance of systemic immunosuppression and side effects. In the absence of financial considerations, vedolizumab is increasingly being considered the first-line biologic in UC, especially in the older population who are at increased risk of infections and malignancies or younger patients with such comorbidities. While vedolizumab is approved as an induction and maintenance agent, it's relatively slow onset of action (compared to anti-TNF agents) means that it is primarily employed due to its maintenance properties and precludes it’s use over infliximab in severe disease (and especially hospitalized acute severe UC), except in the context of bridging co-induction therapy with either steroids or cyclosporine.83,84 Furthermore, though vedolizumab is approved for use in CD, the trial data are not as impressive as for UC, and as such it is less frequently considered a first-line therapy in this condition, especially small bowel CD. Also, while the gut specificity is promoted with respect to the safety of vedolizumab, this property theoretically limits its efficacy in the treatment of patients with significant extra-intestinal manifestations,11 though a recent multicenter cohort study suggested vedolizumab may have some benefit with resolution of inflammatory arthritis in close to half of patients.85

Ustekinumab is currently approved for CD only. Efficacy of ustekinumab in CD subtypes including perianal disease, extra-intestinal manifestations, and optimal positioning in CD relative to the existing biologic classes of anti-TNF and anti-integrin agents remains to be defined. Based on the most recent 2018 American College of Gastroenterology clinical guidelines, lacking such data, the choice of first biologic is at the discretion of the provider and patient according to individual risk–benefit preferences.86 Due to financial considerations, despite the practicality and favorable safety profile of ustekinumab, it is generally not utilized before anti-TNF agents in the absence of specific safety concerns. Additionally, there is still uncertainty about the efficacy of ustekinumab for endoscopic and cross-sectional healing,87 and thus anti-TNF agents remain the biologic of choice in patients with severe endoscopic disease and complex perianal fistulas.

OPTIMIZING CURRENTLY AVAILABLE BIOLOGIC THERAPIES IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Given the limited number of biologic classes currently available and their variable efficacy across IBD patients as a whole, especially when considering more stringent end points such as mucosal healing,9 strategies have been devised to try and optimize the use of biologics in clinical practice.88 Most of these strategies are best supported by data in the setting of the anti-TNF-α agents, which are both most commonly used and have been available for routine clinical care for the longest time period.

Continuous therapy with avoidance of drug holidays

As biologics are foreign protein-based substances, they can stimulate an immunological response resulting in the production of anti-drug antibodies. Anti-drug antibodies, whether neutralizing or non-neutralizing, can impair safety by leading to drug reactions (including infusion reactions ranging from minor lip swelling to serum-sickness-like symptoms such as joint pains, and even anaphylaxis) as well as diminish efficacy by accelerating biologic drug clearance, while neutralizing antibodies also reduce therapeutic activity by inhibiting epitope binding.89 It has been demonstrated that intermittent exposure to biologic agents with intervening “drug holidays,” where the serum biologic drug level falls to zero is the greatest risk for developing anti-drug antibodies and loss of response with worse outcomes.90–92 The use of intermittent dosing was commonly employed early after the introduction of infliximab but resulted in a significant proportion of patients developing anti-drug antibodies so the strategy has now shifted to continuous dosing for as long as the biologic remains effective. The same principle is believed to apply to other biologic classes, though limited data available to date suggest that the newer biologic agents, vedolizumab and ustekinumab, may be less immunogenic than the anti-TNF agents.89

Therapeutic drug monitoring

The development of biologic drug assays has also profoundly improved our ability to optimize biologic therapy in IBD. The one size fits all dosing schedule dictated by the registration trials of the various biologics does not take into account the tremendous inter-patient and intra-patient variability in biologic therapy pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, dependent on a number of factors including but not limited to body weight, inflammatory burden, and albumin level.93 The ability to measure trough drug levels and anti-drug antibodies enables a degree of flexibility and precision medicine, tailored to the specific patient at a specific moment in time (Table 3). While it is clear that the absence of anti-drug antibodies and the presence of detectable trough drug level is desirable, what remains unclear are the exact significance of non-neutralizing antibodies in drug tolerant assays along with the optimal drug trough level for clinical efficacy.94 Trough drug levels of greater than 5 μg/mL for infliximab and 5–7.5 μg/mL for adalimumab have been advocated,95 though some studies suggest higher levels may be beneficial in certain clinical scenarios such as perianal disease.96 One study suggested that different infliximab drug levels may be required based on whether the goal is clinical, biochemical, or endoscopic outcomes, with higher levels required for mucosal healing.97 Another contentious issue is the role of “reactive drug monitoring” in response to a change in clinical or endoscopic findings versus “proactive drug monitoring” in an attempt to anticipate and avoid deterioration in such end points, while reactive drug monitoring has widespread acceptance, there is debate about the role of proactive drug monitoring.98 This issue was investigated in the TAXIT trial,99 which showed no difference between proactive and reactive biologic drug monitoring but there were limitations in this study including short follow-up period (1 year) and the fact that all patients were initially optimized based on drug level at study entry. The TAILORIX study100 also showed no improvement in clinical, endoscopic, and corticosteroid-free remission with proactive as opposed to reactive drug monitoring, though the target trough serum infliximab level of greater than 3 μg/mL was likely suboptimal.

Table 3.

Interpretation of biologic drug trough levels and anti-drug antibodies in patient with ongoing disease activity

| No detectable/sub-therapeutic drug level | Therapeutic drug level | |

|---|---|---|

| No detectable antibodies | Confirm compliance Consider increasing biologic dose or frequency |

Switch biologic (different class with alternative mechanism of action) |

| Detectable antibodies | Switch biologic (can be within same class), and consider combination therapy with immunomodulator to minimize future antibody formation | If low titer antibody and low normal drug level can consider increasing biologic dose or frequency ± combination therapy with immunomodulator If high titer antibody, likely need to switch biologic and consider combination therapy with immunomodulator to minimize future antibody formation |

Combination therapy with immunomodulators

Combining biologic agents with immunomodulators, such as thiopurines or methotrexate, (combination therapy) have been another strategy implemented to optimize biologics. The reasoning behind this is twofold—first, because it was proposed that there would be a synergistic effect by utilizing two drugs with differing mechanisms of efficacy and second, as the concomitant use of immunomodulators was believed to reduce the immunogenicity of biologic agents and the likelihood of developing anti-drug antibodies. Concerns existed about the safety of the combined immunosuppression, especially after reports of the rare but fatal development of hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma when combining anti-TNF-α agents with thiopurines.101 However, it has since become apparent that the risk of this rare condition, for which young males are at highest risk, is predominantly due to thiopurine use.15 Thiopurine use is also associated with increased risk of lymphoma in general, and while combination therapy of thiopurine and anti-TNF-α agents increases the relative risk of lymphoma slightly more,14 the absolute risk remains low in most populations with the elderly at the greatest absolute risk. Thus, the combination of thiopurines and anti-TNF-α biologics is generally avoided in young males, especially those who are EBV negative, and elderly.102,103 Proof of the improved efficacy of combination therapy over biologic monotherapy came in the form of the landmark SONIC study in CD, where the combination of infliximab and azathioprine was better than either therapy alone.104 The findings of this study were replicated in the UC SUCCESS study in UC.105 However, the reason for the improved outcomes with combination therapy remains unclear. A recently published post hoc analysis of the SONIC study with the cohort stratified into quartiles based on anti-TNF-α drug level suggested that the benefit was largely related to the drug level of the anti-TNF-α agent.106 This raises the possibility that optimizing anti-TNF-α dosing with increased frequency/intensity (financial costs notwithstanding) may largely overcome the need for combination therapy though a controlled trial would ultimately be needed to answer this question.

Treat to target with focus on mucosal healing/tight control

Another strategy optimizing the use of biologics adopted from the rheumatological experience is the concept of treating to a pre-specified target beyond mere symptom control. No longer is the goal of treatment, the elimination of symptoms as subclinical disease may persist and later lead to complications and loss of function that may be irreversible. Rather, there is a shift toward normalization of biochemical, radiologic, endoscopic/mucosal, and even potentially histologic evidence of disease activity to achieve “deep remission” for optimal disease control.107 Such a strategy involves pre-emptive monitoring of inflammation markers (both serum—CRP, ESR and fecal such as calprotectin), colonoscopy, and biopsies in the case of UC and colonic CD+/− MR enterography or pelvis in small bowel and perianal CD to identify evidence of disease activity recurrence it becomes clinically apparent. The CALM study of 244 CD patients was the first controlled trial in IBD to demonstrate that biologic therapy escalation based on biomarkers in addition to symptoms led to superior patient outcomes than management based on symptoms alone (46% vs 30% achieved primary end point of mucosal healing at week 48).108 This concept is also evident in the changing paradigm of the treatment of post-operative CD, with the early institution of monitoring and therapeutic escalation to prevent diseases recurrence before symptoms as demonstrated by the POCER study.109

Impact of early institution of biologic therapy

While not all patients with IBD will ultimately need biologic therapy over their disease course, there is a body of evidence that suggests that in those who do, administration of biologic therapy early in the disease course is associated with improved outcomes,110,111 implying there is a limited “window of opportunity” to optimally act in the initial stages of the disease.88,112 Though it is not possible to precisely determine the course an individual’s disease will take, certain predictors have now been identified that forecast a likely more severe disease course where biologics will be required and should be instituted early. These include early age of diagnosis, perianal disease, fistulizing disease, rapid disease progression, and prior surgery among others.113–115 Predictive models incorporating such factors have now been developed to help guide clinicians and patients in individualizing therapeutic decision-making.116 While the biologic agents have disease modifying properties, this is dependent on their utilization during the initial inflammatory phase before irreversible structural and functional tissue damage due to fibrosis and tissue remodeling with resultant stricturing, fistula formation, and loss of bowel compliance has occurred. Unfortunately, despite proven efficacy, either exaggerated safety concerns (especially relative to immunomodulators or chronic steroid use) or financial factors related to costs limit their early implementation with a need in many countries to have failed a therapeutic trial of cheaper non-biologic alternatives (5-ASAs, immunomodulators) first before being escalated to biologic therapy.

De-escalation

One of the most important questions with regard to biologic therapy which is still uncertain is whether in stable patients well controlled on biologic therapy it is reasonable to stop the biologics without precipitating diseases recurrence, and if so, how to best predict which patients and the optimal strategy for doing so.117 The best evidence to date comes from the STORI trial, which showed in patients on combination therapy with an immunomodulator and infliximab, a significant disease relapse rate on cessation of infliximab therapy of ~50% at 1 year, though a substantial proportion of these patients (88%) could be recaptured with re-institution of infliximab therapy.118 In this study, on multivariate analyses, risk factors for relapse included male sex, the absence of surgical resection, leukocyte counts >6.0 × 109/L, and levels of hemoglobin <145 g/L, C-reactive protein >5.0 mg/L, and fecal calprotectin >300 μg/g. While it remains unclear, de-escalation of biologic therapy is probably best limited to patients who have had longstanding remission, not only clinical but also biochemical and endoscopic remission with sustained mucosal healing, and potentially even histologic normalization, coupled with intensive monitoring post cessation for early signs of disease relapse. Ongoing studies, including the European multicenter Biocycle project and SPARE study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02177071), will hopefully provide more clarity on this issue.

WHAT IS ON THE HORIZON

A number of important developments are forecast to change the state-of-the-art paradigm in IBD in the near future including new biologics and targeted small-molecule agents, personalization of biologic treatment based on defined predictors of therapeutic outcome, and combination biologic therapy.

New biologics

A range of new biologic therapies, directed toward either existing or new cellular targets important in the inflammatory process in IBD, are at various stages of development and likely to substantially expand our therapeutic armamentarium (Fig. 1).

Leukocyte trafficking blockers including new anti-integrins and anti-MAdCAM agents

There are a number of additional leukocyte trafficking antagonists being evaluated. Abrilumab (AMG 181) is another gut selective α4β7 integrin antagonist, but unlike vedolizumab is subcutaneous in administration, that has completed phase 2b trials.119,120 Meanwhile, etrolizumab is a β7 antagonist, which inhibits both α4β7 and αEβ7 (blocking interaction with MAdCAM-1 and E3cadherin, respectively) but avoiding blockade of α4β1 that is responsible for CNS leukocyte trafficking. E-cadherin is found on epithelial cells and is involved in intestinal intraepithelial leukocyte localization.41,121 Etrolizumab has shown promise in phase 2b trials122 and has now entered phase 3 program for both UC and CD. Furthermore, a novel agent that targets the α4β7 ligand MAdCAM-1, the fully human monoclonal antibody PF-00347659, has encouraging phase 2 data in UC.123

Anti-IL-12/23 and specific anti-IL-23 agents

Ustekinumab, already approved for CD, has completed phase 3 studies in UC, and if approved would be the first in class available for UC. Additional IL-12/23 antagonists that target the p40 subunit such as briakinumab have also been evaluated124 but are not being advanced. Given the potential issues with IL-12 blockade, perhaps of greater interest and potential are the new monoclonal antibodies that specifically bind the p19 subunit and are thus specific for IL-23 only. Brazikumab125 and risankizumab126 are such IL-23-specific antagonists that have shown efficacy in phase 2 trials in CD.

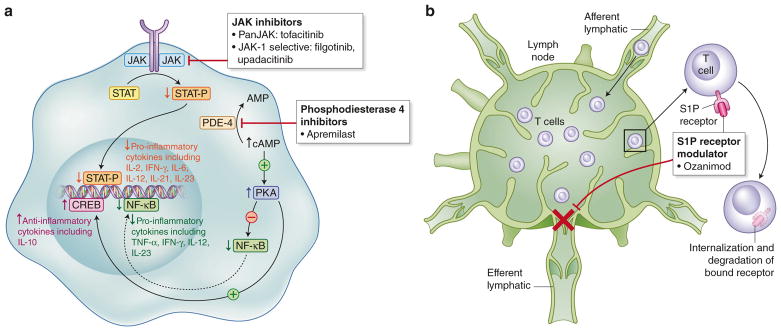

New targeted small molecules

In addition to biologics, there is now renewed interest in the potential of small molecules that are specifically targeted and have the ability to disrupt intracellular signaling pathways crucial to IBD pathogenesis (Fig. 2). These agents have possible advantages relative to biologics including potency due to the ability to interfere with common downstream intracellular pathways that result from the convergence of several extracellular processes, oral administration as they are not protein-based structures and less subject to enzymatic degradation, as well as the lack of immunogenicity which offers the potential of intermittent “on–off” dosing without resultant antibody formation and loss of response.

Fig. 2. Mechanism of action of new investigational small-molecule agents in IBD.

(a) JAK janus kinase, STAT signal transducer and activator of transcription protein, PDE4 phosphodiesterase type 4, cAMP cyclic adenosine monophosphate, PKA protein kinase A, NF-κB nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, CREB cAMP response element-binding protein, (b) S1P sphingosine-1 phosphate

Janus kinase inhibitors

The janus kinase (JAK) proteins are intracellular tyrosine kinases that transduce cytokine-mediated signals in response to binding to cell surface receptors via the JAK–STAT phosphorylation pathway, resulting in nuclear transcription of effector proteins.127 Cytokines implicated in IBD that signal through this mechanism include IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-23.128 The first in class tofacitinib is a non-selective JAK inhibitor (though it preferentially inhibits JAK 1 and JAK 3) that is already approved for use in rheumatoid arthritis.129,130 The phase 3 OCTAVE studies of tofacitinib in moderate-to-severe UC confirmed its efficacy as both an induction and maintenance agent,131 and it is currently under review by the FDA. There are other JAK inhibitors under development, most notably the JAK-1 selective filgotinib132 and upadacitinib,133 which have shown phase 2b efficacy in CD. However, given the extensive immunological effects of these agents that result from blockade of multiple cytokine pathways and safety issues such as the potential for herpes zoster reactivation, the risk–benefit ratio of these agents need to be further defined and may limit their application.134

Sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor modulators

Sphingosine-1 phosphate (S1P) receptors control several immunological processes, including regulation of lymphocyte trafficking from peripheral lymphoid organs which is predominantly mediated through the subtype 1 receptor.135,136 Internalization of the S1P subtype 1 receptor in response to agonist binding results in lymphocyte sequestration in lymph nodes and prevents their egress into the circulation and inflamed tissues, reflected by peripheral lymphopenia. Fingolimod, the first-in-class S1P receptor modulator approved for use in MS, non-specifically blocks S1P and while effective had associated adverse events (cardiovascular and liver) secondary to this lack of selectivity.137 More selective agents within this class are under development for use in a variety of conditions, including IBD, notably ozanimod, an S1P receptor modulator specific to subtypes 1 and 5. Ozanimod was shown in a phase 2 trial in UC to have a benefit in inducing clinical remission and mucosal healing at the higher test dose of 1 mg daily138 and has now progressed to phase 3 studies.

Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors

Phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) is an intracellular enzyme responsible for the breakdown of cAMP, which in turn regulates immune cell responses through the production of multiple cytokines. Increases in intracellular cAMP due to PDE4 inhibition actually downregulates production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ, TNF, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-23 relative to anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10.139 Apremilast is a PDE4 inhibitor, currently approved for use in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.140,141 This medication is currently under investigation in UC, with a recent phase 2 study demonstrating improved clinical remission, biomarker levels and mucosal healing with apremilast 30 mg bid relative to placebo after 12 weeks.142

SMAD7 inhibitors

The immunoregulatory cytokine TGF-β1 has important anti-inflammatory actions but is subject to inhibition by the protein SMAD7.143,144 Mongersen is an oral antisense oligonucleotide that specifically binds to SMAD7 messenger RNA and prevents its transcription by causing RNase-mediated degradation, in turn upregulating TGF-β1 signaling. There was considerable interest in mongersen after a phase 2 study demonstrated markedly superior clinical outcomes relative to placebo though no endoscopic outcomes were assessed145; a later study assessing endoscopic outcomes in 63 active CD at a variety of treatment durations showed endoscopic improvement in 37%.146 However, the subsequent phase 3 trial was suspended due to futility after interim analysis, and it is unclear if medications in this class will undergo further development.

Personalization of biologic therapy/predictors of response or failure

An area of biologic therapy that has been relatively poorly explored is the concept of personalized health care or tailoring therapeutic decisions based on the individual. While overall clinical and biomarker predictors of poor outcome have been established, what has been lacking is an ability to personalize the choice of specific biologics based on an individual’s unique biochemical or genetic predictors of response or failure, as is now being employed in the oncology field. However, data are now starting to emerge to help inform on biologic choices in individuals, especially with new biologics in development.

Integrin αE with etrolizumab

As highlighted above, etrolizumab (a monoclonal antibody against the β7 integrin subunit) has shown efficacy in UC and has now entered phase 3 studies. On a retrospective analysis of data collected from the phase 2 trial, higher levels of granzyme A and integrin αE messenger RNA expression in colon tissues identified UC patients most likely to benefit from etrolizumab, with expression levels decreasing upon etrolizumab administration in high biomarker patients.147

IL22 with brazikumab

Brazikumab, a monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits interleukin 23, was associated with clinical improvement in a phase 2a study in CD patients.125 In this trial, higher baseline serum concentrations of IL-22, which is induced by IL-23, were associated with greater likelihood of response to brazikumab.

Oncostatin M in refractory anti-TNF

Despite the emergence of new biologics, the anti-TNF-α agents remain the most commonly utilized. Recently, it has emerged from both animal model data and a retrospective review of anti-TNF-α therapy trial patients that high pre-treatment expression of oncostatin M (OSM), a member of the IL-6 cytokine family, is strongly associated with failure of anti-TNF-α therapy and as such may prove a valuable biomarker for determining suitability for this treatment class.148 The study authors propose OSM mediates intestinal inflammation through enteric stromal cells, promoting their production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, with effects potentially synergistic with those of TNF. However, whether OSM expression is specific to just poor response to anti-TNF therapy or a predictor of more resistant disease to existing IBD therapies in general is unclear.

Gastrointestinal microbiome characteristics and response to vedoli-zumab

While the gastrointestinal microbiota is known to play a crucial role in IBD pathogenesis, the interaction between the structure and function of the enteric microbiota and the efficacy of immunologically directed biologic therapies that form the basis of current IBD treatment are largely unknown. A recent proof-of-concept study that prospectively assessed fecal metagenomes from 85 IBD patients commencing vedolizumab found that responsive patients were characterized at baseline by higher abundance of butyrate producers such as Roseburia inulinivorans along with enrichment of particular microbial metabolic pathways including branched chain amino acid biosynthesis.149 Further work is required to better define the likely crucial relationship between patient microbiota phenotype and responsiveness to biologic therapies.

Combination of biologics

It was initially felt that the safety risks of combined biologics would be too great due to blockade of multiple pathways involved in inflammation and immunosurveillance. However, the excellent safety profile of the gut-specific integrin blocker vedolizumab54 and recently approved for CD IL-12/23 antagonist ustekinumab,55,150 coupled with growing reassurance from the accumulated safety data for the anti-TNF-α agents12,151 means that combination biologic therapy is now being considered a realistic potential treatment option, notwithstanding the associated financial costs. A recent systematic review has summarized the limited available literature to date on combining biologics across a number of conditions.152 They identified case reports and series in the dermatologic literature while a few controlled trials combining biologics have been conducted in rheumatoid arthritis, which failed to show improved efficacy, but these most commonly involved biologics not utilized in IBD such as etanercept, anakinra, abatacept, and rituximab.153–155 In the IBD literature there have been a few case reports or series156–159 suggestive of possible benefit and one published exploratory short-term controlled trial of combination biologic therapy, examining the safety and tolerability of concurrent natalizumab in 79 active CD patients despite infliximab therapy.160 In this study, concurrent biologic therapy was well tolerated with no difference in adverse events noted between the two groups while there was also a trend toward improved disease activity. There is an open label prospective study, EXPLORER (Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT02764762), currently underway to determine the effect of triple combination therapy with an anti-integrin (vedolizumab), an anti-TNF-α agent (adalimumab), and an immunomodulator (oral methotrexate) on endoscopic remission in participants with newly diagnosed moderate-severe Crohn’s disease stratified at higher risk for complications, which will provide further information on the efficacy and safety of combination biologic therapy.

PATHWAYS THAT EXACERBATE IBD

Although the various chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disorders across the different organ systems share many similarities, there are distinct differences, which are reflected in the conflicting efficacy of certain biologic agent’s dependent on disease type. While the anti-TNF-α agents have largely been shown to be effective across all systemic chronic inflammatory disease states, this has not proven to be the case when some other agents have been tested in IBD.58

Anti-IL-17 therapies

IL-17A stimulates recruitment of neutrophils and other leukocytes to local tissue.161,162 The anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody secukinumab is approved for use and highly effective in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis.163–165 With the Th17 pathway also implicated in CD, secukinumab, was investigated in this condition but showed no efficacy over placebo, actually associated with a worse disease outcome and possible disease exacerbation.166 Similarly, a phase 2 study of brodalumab (a human anti-IL-17 receptor monoclonal antibody) in CD was terminated early due to a disproportionate number of cases of worsening CD.167 This is consistent with some mouse studies, in which neutralization of IL-17A in the DSS acute mucosal injury model actually led to worsening of colitis and stimulation of CD4+ T cell and granulocyte infiltrates.168 There are a number of reasons that may explain the conflicting outcomes with combined IL-12/23 or IL-23-specific blockade as opposed to IL-17-specific blockade.58 These include potential compensatory increase in Th1 cells,169 impaired intestinal epithelial barrier function, decreased antimicrobial protein production,170 and increased pre-disposition to fungal infections171,172 with targeted IL-17 inhibition. While there have been several reports of worsening of established IBD with these agents,173 what is more controversial and as yet unclear is whether they lead to an increase in de novo cases of IBD above and beyond what would be expected by chance. Notably, a review of an integrated database of seven ixekizumab (another anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody) psoriasis trials, including 4209 patients (6480 patient-exposure years), suggested incident cases of CD or UC were uncommon (<1%).174

Anti-B cell (CD-20) therapies

B cell depletion therapies such as rituximab have proven to be effective in a range of autoimmune conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and ANCA-associated vasculitidies.175 However, while the adaptive immune system likely contributes to the pathogenesis of IBD, B-cell-directed therapies have been disappointing in IBD.176 There have been reports of IBD exacerbation177 and even de novo cases of IBD178–180 with rituximab (anti-CD-20 monoclonal antibody), suggesting enteric B cells may be protective in IBD with regulatory and anti-inflammatory functions. Indeed, regulatory B cells can produce IL-10, which has multiple immunoregulatory functions and is considered critical for mucosal homeostasis. In the one small controlled trial of rituximab in 24 UC patients, while there was no evidence of disease worsening it was not associated with any therapeutic benefit.181,182

Oncologic biologic checkpoint inhibitor therapies

Some of the recent checkpoint inhibitor biologic therapies utilized in oncology that work by stimulating the activity of cytotoxic T cells have not surprisingly been associated with exacerbation of colitis. These include the cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) antagonists such as ipilimumab which are approved for use in melanoma and function by blocking inhibitory signals from antigen-presenting cells to cytotoxic T cells.183 The enterocolitis induced by CTLA-4 antagonists mimic the gastrointestinal features often seen in patients with CTLA-4 haploinsufficiency.184 The class of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) antagonist checkpoint inhibitors, such as nivolumab, have also been reported to induce colitis.185,186 Such cases of drug-induced colitis often require medication discontinuation and/or treatment with either steroids or infliximab.

THERAPEUTIC INSIGHTS FROM IBD CASES DUE TO MONOGENETIC DEFECTS IN IMMUNE HOMEOSTASIS

Though rare, cases of very early onset IBD due to monogenetic defects in key proteins central to an intact immune homeostasis provide powerful insights into not only underlying disease pathogenesis, but also potential therapeutic targets and future drug development. A spectrum of over 50 monogenetic variants associated with IBD-like intestinal inflammation has been identified including those linked to T and B cell defects (various forms of CVID, SCID, and hyper IgM syndrome), defects in immunoregulation including regulatory T cells and IL-10 signaling (IL-10 or IL-10 receptor), phagocytic defects such as chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) and other disorders such as Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome.187 Such monogenetic forms of disease are typically unresponsive to standard biologic therapies used in IBD, with many variants ultimately requiring allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. However, particular monogenetic variants may be responsive to pathway-specific biologics not typically used in conventional IBD.188 Cases of monogenetic IBD due to mevalonate kinase deficiency, characterized by hyperinflammation and inflammasome activation with excessive production of IL-1β, have been successfully treated using IL-1βγreceptor antagonists (anakinra).189,190 Furthermore, there are reports of patients with mutations in LRBA, which is associated with reduced surface expression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) on T cells and results in CVID, being responsive to treatment with the CTLA-4–immunoglobulin fusion drug abatacept.191

Additionally, there is now increasing evidence to suggest that there is more of a spectrum of genetic variants and disease pathogenicity, with shared metabolic pathways where various common and Mendelian genes interconnect, and possibly a continuum of functional variants on the individual gene level.192,193 As further genetic causes of IBD are characterized, new potential pathways and associated molecular targets for biologic therapy will likely emerge.

CONCLUSION

Biologic agents are the most effective therapies currently available for the treatment of IBD and are the foundation of treatment of moderate-to-severe disease. They have led to a significant improvement in clinical and endoscopic outcomes, along with morbidity associated with hospitalization and surgery in IBD patients. State-of-the-art biologic treatment algorithms will continually evolve with greater understanding of how to optimally use and personalize existing biologics, along with the emergence of newer biologic and targeted small-molecule agents directed toward different factors and pathways implicated in disease pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to thank Jill Gregory, Associate Director of Instructional Technology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai for creating the figure illustrations. This work was supported by the following grants: Mt Sinai (New York) SUCCESS fund -GCO14-0560 (JFC), Takeda Pharmaceuticals Investigator Initiated Research Grant (JFC), NIH/NIDDK R01 DK112296 (SM), Rainin Foundation Synergy Award (SM). Additionally, A.K.R. was supported by the Digestive Disease Research Foundation (DDRF).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.P., S.M., and J.F.C. planned the manuscript. S.P. and A.K.R. drafted the manuscript. S. M. and J.F.C. reviewed the manuscript for its intellectual content.

Competing interests: S.P., A.K.R., and S.M. declare no competing interests. J.F.C. has served as consultant or advisory board member for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Celgene Corporation, Celltrion, Enterome, Eli Lilly, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Janssen and Janssen, Medimmune, Merck & Co., Nextbiotix, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc., Pfizer, Protagonist, Second Genome, Gilead, Seres Therapeutics, Shire, Takeda, Theradiag; speaker for AbbVie, Ferring, Takeda, Celgene Corporation. He has stock options with Intestinal Biotech Development and Genefit; he has research grants from AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen and Janssen.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:182–205. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389:1756–1770. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32126-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741–1755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31711-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandborn WJ. The present and future of inflammatory bowel disease treatment. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;12:438–441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomollon F, et al. 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease 2016: part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:3–25. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harbord M, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:769–784. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornbluth A. Infliximab approved for use in Crohn’s disease: a report on the FDA GI Advisory Committee conference. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1998;4:328–329. doi: 10.1002/ibd.3780040415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrow T, Felcone LH. Defining the difference: what makes biologics unique. Biotechnol Healthc. 2004;1:24–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neurath MF, Travis SP. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gut. 2012;61:1619–1635. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandes C, Allocca M, Danese S, Fiorino G. Progress with anti-tumor necrosis factor therapeutics for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Immunotherapy. 2015;7:175–190. doi: 10.2217/imt.14.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vavricka SR, Scharl M, Gubler M, Rogler G. Biologics for extraintestinal manifestations of IBD. Curr Drug Targets. 2014;15:1064–1073. doi: 10.2174/1389450115666140908125453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichtenstein GR, et al. Serious infection and mortality in patients with Crohn’s disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREAT registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1409–1422. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nyboe Andersen N, et al. Association between tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists and risk of cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA. 2014;311:2406–2413. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lemaitre M, et al. Association between use of thiopurines or tumor necrosis factor antagonists alone or in combination and risk of lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA. 2017;318:1679–1686. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyams JS, et al. Infliximab is not associated with increased risk of malignancy or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1901–14 e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Targan SR, et al. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn’s disease. Crohn’s Disease cA2 Study Group. New Engl J Med. 1997;337:1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710093371502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Dullemen HM, et al. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with anti-tumor necrosis factor chimeric monoclonal antibody (cA2) Gastroenterology. 1995;109:129–135. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanauer SB, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sands BE, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. New Engl J Med. 2004;350:876–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutgeerts P, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. New Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanauer SB, et al. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:323–333. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.030. quiz 591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colombel JF, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:52–65. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutgeerts P, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains mucosal healing in patients with Crohn’s disease: data from the EXTEND trial. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1102–11 e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandborn WJ, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:257–265. e1–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandborn WJ, et al. Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. New Engl J Med. 2007;357:228–238. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schreiber S, et al. Maintenance therapy with certolizumab pegol for Crohn’s disease. New Engl J Med. 2007;357:239–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hebuterne X, et al. Endoscopic improvement of mucosal lesions in patients with moderate to severe ileocolonic Crohn’s disease following treatment with certolizumab pegol. Gut. 2013;62:201–208. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schreiber S, et al. Randomised clinical trial: certolizumab pegol for fistulas in Crohn’s disease - subgroup results from a placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:185–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandborn WJ, et al. Subcutaneous golimumab induces clinical response and remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:85–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandborn WJ, et al. Subcutaneous golimumab maintains clinical response in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:96–109 e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreland LW, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:478–486. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van den Brande JM, et al. Infliximab but not etanercept induces apoptosis in lamina propria T-lymphocytes from patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1774–1785. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00382-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perrier C, et al. Neutralization of membrane TNF, but not soluble TNF, is crucial for the treatment of experimental colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:246–253. doi: 10.1002/ibd.23023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitoma H, et al. Infliximab induces potent anti-inflammatory responses by outside-to-inside signals through transmembrane TNF-alpha. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:376–392. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ten Hove T, van Montfrans C, Peppelenbosch MP, van Deventer SJ. Infliximab treatment induces apoptosis of lamina propria T lymphocytes in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2002;50:206–211. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ueda N, et al. The cytotoxic effects of certolizumab pegol and golimumab mediated by transmembrane tumor necrosis factor alpha. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1224–1231. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318280b169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nesbitt A, et al. Mechanism of action of certolizumab pegol (CDP870): in vitro comparison with other anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1323–1332. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butcher EC, Picker LJ. Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science. 1996;272:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akiyama SK. Integrins in cell adhesion and signaling. Hum Cell. 1996;9:181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berlin C, et al. alpha 4 integrins mediate lymphocyte attachment and rolling under physiologic flow. Cell. 1995;80:413–422. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ley K, Rivera-Nieves J, Sandborn WJ, Shattil S. Integrin-based therapeutics: biological basis, clinical use and new drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:173–183. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berlin C, et al. Alpha 4 beta 7 integrin mediates lymphocyte binding to the mucosal vascular addressin MAdCAM-1. Cell. 1993;74:185–195. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90305-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller DH, et al. A controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. New Engl J Med. 2003;348:15–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Targan SR, et al. Natalizumab for the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: results of the ENCORE Trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1672–1683. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sandborn WJ, et al. Natalizumab induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. New Engl J Med. 2005;353:1912–1925. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL. Progressive multifocal leukoence-phalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis. New Engl J Med. 2005;353:369–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Assche G, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn’s disease. New Engl J Med. 2005;353:362–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Honey K. The comeback kid: TYSABRI now FDA approved for Crohn disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:825–826. doi: 10.1172/JCI35179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bellaguarda E, et al. Prevalence of antibodies against JC virus in patients with refractory Crohn’s disease and effects of natalizumab therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1919–1925. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kempster SL, Kaser A. alpha4beta7 integrin: beyond T cell trafficking. Gut. 2014;63:1377–1379. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feagan BG, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. New Engl J Med. 2013;369:699–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandborn WJ, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. New Engl J Med. 2013;369:711–721. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bryant RV, Sandborn WJ, Travis SP. Introducing vedolizumab to clinical practice: who, when, and how? J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:356–366. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Colombel JF, et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2017;66:839–851. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feagan BG, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. New Engl J Med. 2016;375:1946–1960. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Langley RG, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, with and without dosing adjustment, in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from the PHOENIX 2 study through 5 years of follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1371–1383. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Papp K, et al. Safety surveillance for ustekinumab and other psoriasis treatments from the psoriasis longitudinal assessment and registry (PSOLAR) J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:706–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abraham C, Dulai PS, Vermeire S, Sandborn WJ. Lessons learned from trials targeting cytokine pathways in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:374–88 e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lund RJ, Chen Z, Scheinin J, Lahesmaa R. Early target genes of IL-12 and STAT4 signaling in th cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:6775–6782. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Monteleone G, et al. Interleukin 12 is expressed and actively released by Crohn’s disease intestinal lamina propria mononuclear cells. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yawalkar N, Karlen S, Hunger R, Brand CU, Braathen LR. Expression of interleukin-12 is increased in psoriatic skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:1053–1057. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cua DJ, et al. Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature. 2003;421:744–748. doi: 10.1038/nature01355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murphy CA, et al. Divergent pro- and anti-inflammatory roles for IL-23 and IL-12 in joint autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1951–1957. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Duerr RH, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006;314:1461–1463. doi: 10.1126/science.1135245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oppmann B, et al. Novel p19 protein engages IL-12p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity. 2000;13:715–725. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ivanov II, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17 + T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gaffen SL, Jain R, Garg AV, Cua DJ. The IL-23-IL-17 immune axis: from mechanisms to therapeutic testing. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:585–600. doi: 10.1038/nri3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Buonocore S, et al. Innate lymphoid cells drive interleukin-23-dependent innate intestinal pathology. Nature. 2010;464:1371–1375. doi: 10.1038/nature08949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abraham C, Cho J. Interleukin-23/Th17 pathways and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1090–1100. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee Y, et al. Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:991–999. doi: 10.1038/ni.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yosef N, et al. Dynamic regulatory network controlling TH17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2013;496:461–468. doi: 10.1038/nature11981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ahern PP, et al. Interleukin-23 drives intestinal inflammation through direct activity on T cells. Immunity. 2010;33:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eken A, Singh AK, Treuting PM, Oukka M. IL-23R + innate lymphoid cells induce colitis via interleukin-22-dependent mechanism. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:143–154. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zenewicz LA, et al. Innate and adaptive interleukin-22 protects mice from inflammatory bowel disease. Immunity. 2008;29:947–957. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ben-Horin S, Vande Casteele N, Schreiber S, Lakatos PL. Biosimilars in inflammatory bowel disease: facts and fears of extrapolation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1685–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paramsothy S, Cleveland NK, Zmeter N, Rubin DT. The role of biosimilars in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;12:741–751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beck A. Biosimilar, biobetter and next generation therapeutic antibodies. MAbs. 2011;3:107–110. doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.2.14785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Danese S, Gomollon F, Governing B. Operational Board of ECOO. ECCO position statement: the use of biosimilar medicines in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:586–589. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Park SH, et al. Post-marketing study of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) to evaluate its safety and efficacy in Korea. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9(Suppl 1):35–44. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1091309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gecse KB, et al. Efficacy and safety of the biosimilar infliximab CT-P13 treatment in inflammatory bowel diseases: a prospective, multicentre, nationwide cohort. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:133–140. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jorgensen KK, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2304–2316. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Laharie D, et al. Ciclosporin versus infliximab in patients with severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids: a parallel, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1909–1915. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sands BE, Van Assche G, Tudor D, Tan TY. Ne-jj Vedolizumab in combination with steroids for induction therapy in Crohn’s disease: an exploratory analysis of the GEMINI 2 and GEMINI 3 studies. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:S068. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tarabar D, et al. Combination therapy of cyclosporine and vedolizumab is effective and safe for severe, steroid-resistant ulcerative colitis patients: a prospective study. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:S065. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tadbiri S, et al. Impact of vedolizumab therapy on extra-intestinal manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a multicentre cohort study nested in the OBSERV-IBD cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:485–493. doi: 10.1111/apt.14419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lichtenstein GR, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:481–517. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2018.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]