Abstract

Niemann-Pick disease, type C1 (NPC1) is an inborn error of metabolism that results in endolysosomal accumulation of unesterified cholesterol. Clinically, NPC1 manifests as cholestatic liver disease in the newborn or as a progressive neurogenerative condition characterized by cerebellar ataxia and cognitive decline. Currently there are no FDA approved therapies for NPC1. Thus, understanding the pathological processes that contribute to neurodegeneration will be important in both developing and testing potential therapeutic interventions. Neuroinflammation and necroptosis contribute to the NPC1 pathological cascade. Receptor Interacting Protein Kinase 1 and 3 (RIPK1 and RIPK3), are protein kinases that play a central role in mediating neuronal necroptosis. Our prior work suggested that pharmacological inhibition of RIPK1 had a significant but modest beneficial effect; however, the inhibitors used in that study had suboptimal pharmacokinetic properties. In this work we evaluated both pharmacological and genetic inhibition of RIPK1 kinase activity. Lifespan in both Npc1−/−mice treated with GSK’547, a RIPK1 inhibitor with better pharmacokinetic properties, and Npc1−/− :Ripk1kd/kd double mutant mice was significantly increased. In both cases the increase in lifespan was modest, suggesting that the therapeutic potential of RIPK1 inhibition, as a monotherapy, is limited. We thus investigated the potential of combining RIPK1 inhibition with 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) therapy HPβCD has been shown to slow neurological disease progression in NPC1 mice, cats and patients. HPpβCD appeared to have an additive positive effect on the pathology and survival of Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd mice. RIPK1 and RIPK3 are both critical components of the necrosome, thus we were surprised to observe no increase survival in Npc1−/−;Ripk3−/− mice compared to Npc1−/− mice. These data suggest that although necroptosis is occurring in NPC1, the observed effects of RIPK1 inhibition may be related to its RIPK3-independent role in neuroinflammation and cytokine production.

Keywords: Niemann-Pick Disease, type C1, NPC1, Necroptosis, RIP Kinase, RIPK1, RIPK3, 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin

Introduction

Niemann-Pick disease, type C1 (NPC1) is lysosomal storage disease with endolysosomal storage of unesterified cholesterol and sphingolipids [1], NPC1 results from mutation of NPC1 and is inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder [2, 3]. Impaired NPC1 function results in progressive neurodegeneration. Although age of onset and the specific sign/symptom complex can vary among patients, clinically NPC1 is typically characterized by vertical supranuclear gaze palsy, gelastic cataplexy, seizures, cerebellar ataxia, and cognitive impairment [4-6]. The incidence of classical NPC1 has been estimated to be on the order of 1/100,000; however, late onset cases may be more frequent [4, 7]. There are currently no FDA approved therapies for NPC1. Miglustat (Zavesca), a glycosphingolipid synthesis inhibitor, has been shown to have some efficacy [8, 9] and intrathecal 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (VTS-270) appears to significantly reduce neurological disease progression in NPC1 patients relative to historic controls [10]. Although these studies are promising, there remains a critical need to develop additional therapeutic approaches and to evaluate the potential of combined therapy for the treatment of NPC1.

Necroptosis is a specific type of caspase-independent, regulated cell death mediated by receptor interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) or receptor interacting protein kinase 3 (RIPK3) [11-13]. Necroptosis appears to have a role the pathological cascade of lysosomal storage diseases. RIPK3-mediated necroptosis has been implicated in pathology of Gaucher disease [14], and we previously reported that necroptosis contributed to NPC1 pathology in both Npc1 mutant mice and human patient cell lines [15]. Specifically, we demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of RIPK1 delayed the onset of neurological manifestations, delayed cerebellar Purkinje neuron loss and increased the lifespan of Npc1 mutant mice by 16 to 20 percent. We hypothesized that the modest increase in lifespan could be due to either a delay in initiation of treatment until after weaning or the sub-optimal pharmacological properties of Nec1 and Nec1s. The half-lives of Nec1 and Nec1s are 5 minutes and 1 hour, respectively [16]. In this study, we sought to determine the full therapeutic potential of RIPK1 inhibition by comparing Npc1−/− :Ripk1+/+ and Npc1−/− :Ripk1kd/kd mice. The Ripk1kd allele encodes a missense mutation, p.K45A, that abolishes kinase activity and RIPK1-dependent necroptosis without lethality due to the loss of RIPK1 scaffolding function [17]. We also sought to evaluate the potential of RIPK3 inhibition in NPC1 and to investigate the combined efficacy of 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin treatment and necroptosis inhibition.

Methods

Mouse breeding

All animal procedures were approved by the NICHD Animal Care Use Committee. Inbred Balb/c Npc1+/− mice were intercrossed to obtain Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− mice [18]. Balb/c Npc1+/− were crossed with C57bl/6 Ripk1kd/kd (GlaxoSmithKline, Collegeville, PA, USA [17]) or C57bl/6 Ripk3−/− (Genentech, San Francisco, CA, USA, [19]) mice. Due to the resulting mixed genetic background, sibling controls were used. The resulting Npc1+/−:Ripk1kd/+ and Npc1+/−:Ripk3+/− were respectively intercrossed to obtain Npc1−/−:Ripk1+/+; Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd;Npc1+/+:Ripk1+/+ and Npc1+/+:Ripk1kd/kd or Npc1−/−:Ripk3+/+; Npc1−/−:Ripk3−/−; Npc1+/+:Ripk3+/+ and Npc1+/+:Ripk3−/−. Npc1+/+:Ripk1+/+:Ripk3+/+ and Npc1−/−:Ripk1+/+:Ripk3+/+ mice were designated as Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/−, respectively. Comparisons were made using mice sharing the same mixed Balb/c:C57bl/6 background. Pups were weaned three weeks after birth. Water and mouse chow were available ad libitum. Genotyping PCR was performed using tail DNA as previously described for each mouse model [17-19]. A humane survival endpoint was defined as hunched posture, reluctance to move, inability to remain upright when moving and weight loss greater than 30% of peak weight.

Drug treatments

GSK’574 is an orally available inhibitor of RIPK1 that was incorporated into the mouse chow at a concentration of 833 mg·kg−1[20], GSK’574 therapy was initiated at weaning in Balb/c Npc1+/+ (n=24) and Npc1−/− (n=24) mice. HPβCD (Kleptose HPB, Roquette, Vacquemont, France) was administered as a single subcutaneous injection of 4000 mg·kg−1 on day of life 7.Efficacy of combined GSK’547 and HPβCD therapy was tested in Balb/c Npc1+/+ (n=12) and Npc1−/− (n=12) mice. We also evaluated the efficacy of HPβCD in RIPK1 deficient mice. For this study Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd (n=29) and Npc1−/− (n=28) received a single subcutaneous injection of 4000 mg·kg−1 HPβCD. For each experimental group, 6 additional mice were sacrificed at 7 weeks of age for pathological analysis.

Immunohistochemistry and analysis

Mice were euthanized at 7 weeks by CO2 asphyxiation and transcardially perfused with 24 ml of ice-cold PBS followed by 24 ml of ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4. Brain tissue was further post-fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 24 hours and then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose at 4°C. A cryostat was used to obtain 20 μm thick parasagittal cerebellar tissue sections. Tissues sections were floated on 1X PBS with 0.25% Triton X-100 and 10% goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and then incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse anti-mouse calbindin 28K (1:400, Sigma-Aldrich, St-Louis, MO, USA), rabbit anti-mouse IBA1 (1:200, Wako, Richmond, VA, USA), or chicken anti-GFAP (1:400, Novus, Littleton, CO, USA). Sections were washed three times at room temperature for 5 minutes each with PBS/0.25% Triton X-100. Goat secondary antibodies were conjugated with either Alexa-594, Alexa-488 or Alexa-642 (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, 1:1000). Sections were incubated with the secondary antibody for one hour at room temperature in 1X PBS/0.25% Triton X-100/10% Goat serum. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 3342 (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, 1:5000, Waltham, MA, USA) in PBS/0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes at room temperature. The sections were then washed twice with PBS/0.25% Triton X-100 before transfer to gelatine coated slides (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA). Sections were washed once with water, dried and then mounted using Mowiol 4-88 (Sigma-Aldrich, St-Louis, MO, USA). Images were obtained using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) fitted with an automated scanning stage, Colibri II LED illumination and Zeiss ZEN2 software using a high-res AxioCam MRm camera and a 20x objective. Each fluorophore channel was pseudo-colored in ZEN2 and exported as an 8 bit tiff file. Immunofluorescence staining analysis was performed in Fiji version 1.51n [21]. GFAP density used the “moments” thresholding method at 95% for the measurement. Microglia projection length was measured using the built-in measurement tool and scaling to convert pixel to μm as previously described [22]. Purkinje cells were counted by measuring the number of calbindin positive cell bodies with a recognizable dendritic tree or axonal projection remaining within a given cerebellar lobule. The data were expressed as the number of Purkinje cells per l00μm of Purkinje cell layer: granule cell layer interface. Analyses were performed on three sections per brain for six animals per group.

Statistical Analyses

Results are presented as mean ± S.D. The Mann-Whitney test was used to statistically compare two groups. The Mantel-Cox log rank test was used to compare survival curves. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical calculations were performed with GraphPad Prism software version 5 (San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Characterization of Npc1−/−:Ripk3−/− double mutant mice

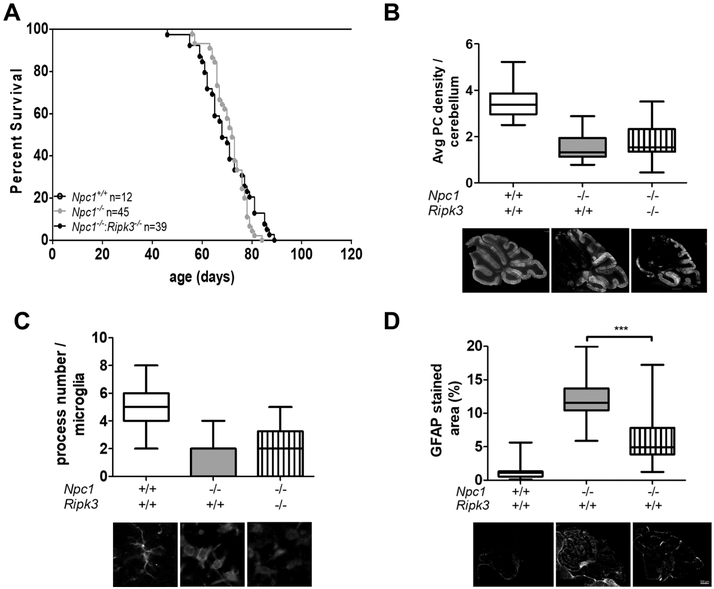

Our previous work demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of RIPK1 partially ameliorated the pathological effects due to loss of NPC1 function [15]. However, the potential role of RIPK3 in NPC1 pathology was not explored. To evaluate the role of RIPK3 in NPC1, we compared disease progression in Npc1−/−:Ripk3+/+ and Npc1−/−:Ripk3−/− mice.

No significant survival difference was observed when comparing Npc1−/−:Ripk3+/+ and Npc1−/−:Ripk3+/+ mice (Fig. 1A). Mean survival was 71 ± 6 days (n=45) for the Npc1 mutant mice compared to 70 ± 10 days (n=39) for the double Npc1 and Ripk3 mutant mice. We also did not observe any difference in cerebellar Purkinje cell density (Fig. 1B) or microglial activation (Fig. 1C) in cerebellar tissue from 7-week old animals. Although variable, astrogliosis, quantified by staining for Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP), appeared to be decreased in the Npc1−/−:Ripk3−/− mice compared to the Npc1−/−:Ripk3−/− mice (Fig. 1D). Cerebellar GFAP staining decreased toward normal from 12.3 ± 3.4 to 6.2 ± 4.1 percent (p<0.001). Altogether, the inhibition of RIPK3 activity significantly decreased astrogliosis, we observed no effect on survival, Purkinje cell density, or microglia activation in Npc1 mutant mice. These data suggest that astrogliosis and RIPK3 do not play a critical role in the NPC1 pathological cascade

Figure 1. Characterization of Npc1−/−:Ripk3−/− double mutant mice.

A) Kaplan-Mayer survival curves for Npc1+/+ (n=12), Npc1−/− (n=45), Npc1−/−:Ripk3−/− (n=39). No Npc1+/+ mice died in the plotted time-period. Survival of Npc1 mutant and Npc1:Ripk3 double mutant mice was not significantly (p=0.40) different. B) Box and whisker plot of average cerebellar Purkinje neuron (PN) density per 100 μm. Representative photomicrographs of sagittal sectioned cerebellar tissue stained with anti-calbindin 28K are shown below the graph. Anti-calbindin 28K stains Purkinje neurons. Bar is 500 μm. C) Microglia were stained with anti-IBA1 and the number of processes per microglial cell were quantified. Data is presented as box and whisker plots. Representative photomicrographs of IBA1 stained microglia are show below the graphs. D) Sagittal cerebellar sections were stained for Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) and the percent area of positive staining was quantified. GFAP staining was significantly decreased toward normal in the double mutant mice. Representative photomicrographs are shown below the graphs. Bar represents 500 μm. For B, C and D data were obtained from three sagittal sections obtained from six animals corresponding to each genotype.

Pharmacological inhibition of RIPK1

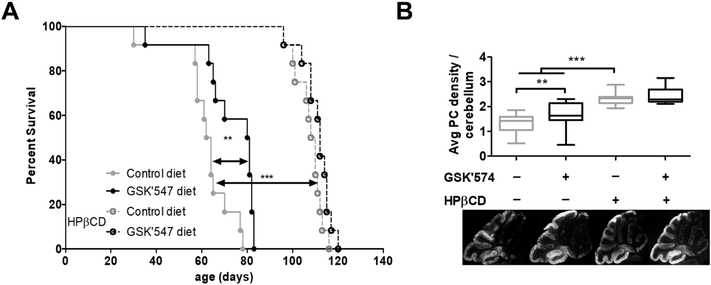

Given our prior results showing a modest, but significant, increased survival of Npc1 mutant mice treated with either Nec1 or Nec1s [15], we wanted to explore the therapeutic potential of a RIPK1 inhibitor with better pharmacological properties. GSK’574 is an orally available RIPK1 inhibitor [20]. Both the increased half-life and dietary administration are likely to lead to improved drug exposure and thus more efficient RIPK1 inhibition. Treatment of Balb/c Npc1−/− mice with GSK’547 significantly increased (p<0.05) the mean survival from a mean of 62 ± 12 days for the untreated mutant mice to 73 ± 15 days for the treated mice (Fig. 2A). This 17% increase in survival was still modest and similar to what we had previously observed with Nec1 and Nec1s. Consistent with increased survival, GSK’547 treatment delayed cerebellar Purkinje neuron loss inNpc1 mutant mice (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Pharmacological inhibition of RIPK1 with GS’C547.

A) Kaplan-Mayer survival curve for Npc1−/− treated with a control diet or mouse chow containing 833 mg·kg−1 of GSK’547. A second cohort of Npc1 mutant mice on either control or GSK’547 chow was treated with 4000 mg·kg−1 of HPβCD. Each experimental group consisted of 12 mice. Comparisons were made using the Log-Rank Mantel-Cox test **P<0.01 and *** P<0.001. B) Box and whisker plot of average cerebellar Purkinje neuron density per 100 μM. Representative photomicrographs of sagittal sectioned cerebellar tissue stained with anti-calbindin 28K are shown below the graph. Data were obtained from three sagittal sections obtained from six animals corresponding to each genotype. *p<0.05 and ***p<0.001 Mann-Whitney test.

We also explored the therapeutic potential of combined HPβCD and GSK’547 treatment. Combination therapy utilizing drugs targeting different aspects of the NPC1 pathological cascade has been reported to be effective in the NPC1 mouse model [23]. As expected from prior work [24-26], a single subcutaneous injection of 4000 mg·kg−1 on day of life 7 significantly (p<0.001) increased survival (Fig. 2A) and delayed cerebellar Purkinje neuron loss (Fig. 2B). Unfortunately, combined HPβCD and GSK’547 treatment appeared to have, if any, a minor therapeutic benefit over HPβCD treatment alone. There was a trend (p=0.07) toward a 4% increase in survival in the combined HPβCD and GSK’547 treated mice (111 ± 6 days) compared to HPβCD monotherapy (107 ± 6 days), and cerebellar Purkinje neuron density was similar when comparing the combined versus HPβCD monotherapy (Fig. 2).

Characterization of Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kddouble mutant mice

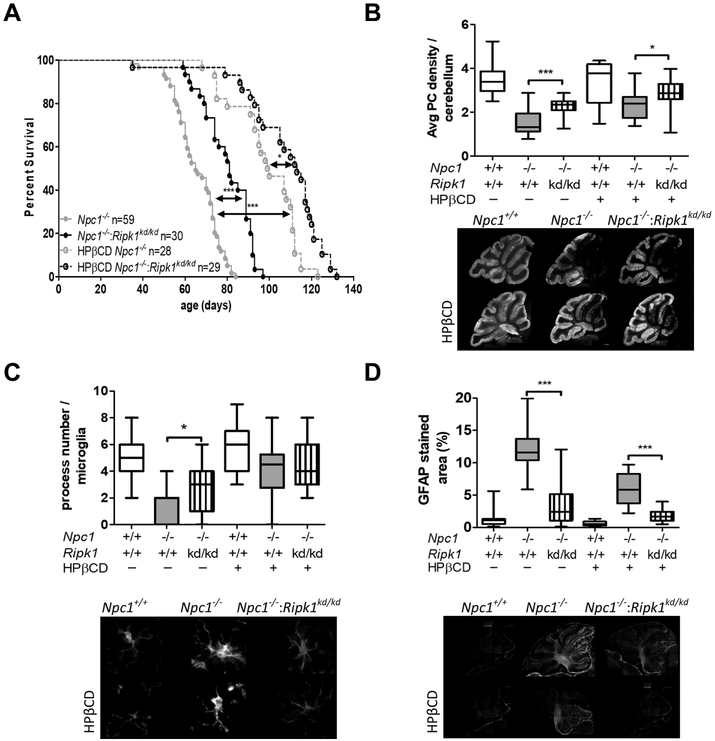

A therapeutic response to pharmacological inhibition of RIPK1 may be limited by two factors: the degree of RIPK1 inhibition achieved and administration starting at weaning (~3 weeks of age). We thus sought to define the full potential of RIPK1 inhibition by comparing the phenotype of Npc1−/−:Ripk1+/+ (Npc1−/−) and Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd double mutant mice. Consistent with our pharmacological studies showing a survival advantage when Npc1 mutant mice were treated with RIPK1 inhibitors, we observed significant (p<0.001) increased mean survival of Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd double mutant mice (80 ±11 days, n=30) compared to Npc1−/− mice (65 ±11 days. n=59) (Fig.3A). This 21% increase in survival with genetic ablation of RIPK1 kinase activity is similar to the percentage increase observed using pharmacological inhibition of RIPK1. Consistent with increased length of survival, we also observed a significant (p<0.05) increase in cerebellar Purkinje cells at 7-weeks of age in the Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd mice compared to Npc1:Ripk1+/+ mice (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Characterization of Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd double mutant mice.

A) Survival was significantly increased (p<0.001) in Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd (n=30) mice compared to Npc1−/−(n=59) mice on the same mixed C57B1/6 and Balb/c genetic background. Survival was also increased in Npc1−/− mice treated with 4000 mg·kg−1 of HPβCD (n=28, p<0.001). Consistent with an additive effect, survival was further increased in Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd mice treated with 4000 mg·kg−1 of HPβCD (n=29, p<0.05). B) Average cerebellar Purkinje neuron density per 100 μM was increased toward normal in Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd mice and further increased in Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd mice treated with HPβCD. Representative calbindin 28K stained sagittal sections are shown below the graphs. C) Quantification of microglial processes were consistent with a decreased activated morphology in Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd mice compared to Npc1−/− mice (p<0.05). No difference was observed in HPβCD treated animals. D) GFAP staining decreased toward normal in Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd mice compared to Npc1−/− mice (p<0.001), and consistent with an additive effect, decreased further in HPβCD treated animals (p<0.001). For B, C and D data were obtained from three sagittal sections obtained from six animals corresponding to each genotype. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, Mann-Whitney test was used to compare means. Log-Rank Mantel-Cox test was used to compare survival curves.

Microglial cells in Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd cerebellar tissue had a less activated morphology with increased number of processes (p<0.05; Fig. 3C) and consistent with decreased astrogliosis, cerebellar GFAP staining was significantly decreased (p<0.001; Fig. 3D).

We also investigated the therapeutic potential of combined RIPK1 inhibition and HPβCD therapy in the Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd mice. As anticipated, a single subcutaneous injection of 4000 mg·kg−1 HPβCD on day of life 7 increased lifespan from 68 ± 10 to 99 ± 15 days (p<0.001) in the Npc1−/− mice (Fig. 3A). These data differ from the data presented in Figure 2A in that the mice used for this experiment were on a mixed C57B1/6 and Balb/c background and the mice for the former experiment were inbred Balb/c mice. Treatment of the Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd mice with HPβCD further increased lifespan to a mean of 107 ± 20 days. Although we did not observe any significant difference in the number of microglial processes (Fig. 3C), we did observe a significant increase in average Purkinje cell number (Fig. 3B; p<0.05) and decreased cerebellar GFAP staining (Fig. 3D; p<0.001). These later two observations are consistent with the increase lifespan observed inNpc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd micetreated with HPβCD,

Discussion

Our previous work established that necroptosis was functionally involved in the NPC1 pathological cascade and showed that inhibition of RIPK1 function had therapeutic potential [15]. In this paper we extended these initial findings to investigate the therapeutic potential of RIPK3 inhibition and more efficient RIPK1 inhibition. We also evaluated the therapeutic potential of combining RIPK1 inhibition and HPβCD therapy.

The data presented in this paper clearly confirm the involvement of RIPK1 in the NPC1 pathological cascade. Our previous work showed a significant but modest survival increase in Npc1 mutant mice treated with allosteric inhibitors, Nec1 or Nec1s, of RIPK1. The therapeutic efficacy demonstrated in those experiments might have been limited by the poor pharmacokinetic properties of these inhibitors and the intermittent administration. In this paper we extended these studies to evaluate the therapeutic potential of GSK’547. GSK’547 is a RIPK1 inhibitor that can be administered in mouse chow and has better pharmacokinetic properties in comparison to Nec1 and Nec1s [20]. Treating Npc1 mutant mice with GSK’547 decreased cerebellar Purkinje neuron loss and increased survival; however, the increase in survival was not substantially better that what was previously observed with Nec1 or Nec1s. The lack of a more robust response to GSK’547 treatment could be due to incomplete inhibition of RIPK1 or initiation of therapy after weaning. To circumvent these potential limitations and to define the full potential of RIPK1 inhibition, we compared Npc1−/−:RIP1+/+ and Npc1+/+:Ripk1kd/kd mice. The Ripk1kd allele produces a protein that can support RIPK1 scaffolding function but ablates RIPK1 kinase activity [17]. Null Ripk1 alleles are prenatal lethal [27]. Histopathological analysis showed changes toward normal and survival was increased by 21% in Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd mice. This modest increase in survival with early and complete RIPK1 inhibition is similar to that observed with pharmacological inhibition of RIPK1.

HPβCD has been shown to significantly decrease NPC1 pathology and increase lifespan in both the NPC1 mouse [2, 24-26] and cat [28] models. Intrathecal administration of VTS-270, a specific HPβCD, significantly decreased the progression of neurological symptoms in NPC1 patients compared the expected progression rate [10]. We thus explored the therapeutic potential of combined HPβCD treatment and RIPK1 inhibition. We observed a trend toward increased survival in Npc1 mutant mice treated with both HPpCD and GSK’547 and a significant survival benefit in Npc1−/−:Ripk1kd/kd mice treated with HPβCD. These data suggest that this combined therapy may have a limited benefit in the treatment of NPC1.

Interestingly, in contrast to our data supporting a role of RIPK1 in NPC1 pathology, we found that genetic ablation of RIPK3 activity had a minimal effect on NPC1 pathology. Although we observed decreased astrogliosis in Npc1−/−:Ripk3−/− mice compared to Npc1−/− :Ripk3+/+, we did not observe decreased microgliosis, preservation of Purkinje neurons or a change in survival. Both RIPK1 and RIPK3 are components of the necrosome, the protein complex that mediates necroptosis [13, 29. Thus, given the clear data demonstrating necroptosis in Npc1 mutant brain tissue {Cougnoux, 2016 #5], the minimal effect on NPC1 pathology observed after ablating RIPK3 activity was surprising. This suggests that the therapeutic benefit observed with RIPK1 inhibition might be due to inhibition of a necrosome independent function. It is unlikely that this observation is explained by RIPK1-dependent apoptosis. Our prior work showed that increased cellular death of NPC1 fibroblasts was not mitigated by treatment with a caspase inhibitor (F-VAD) and we did not observe either cleaved caspase 3 or 8 in cerebellar tissue [15]. In addition, Erickson and Bernard [30] did not observe any change in disease progression following the neuronal overexpression of Bcl-2, which would be predicted to protect against apoptosis mediated neuronal loss. RIPK1, independent of RIPK3, can mediate inflammatory responses and cytokine production primarily via TLR4/TRIF signaling [20, 31, 32]. Previous work by Suzuki et al. [33] have shown that endolysosomal accumulation of TLR4 contributes to constitutive secretion of interferon-β, IL-6 and IL-8. This group also showed a minor (10%), but significant, increase in survival if the IL-6 gene was disrupted inNpc1 mutant mice. This is consistent with minor to modest increases in survival with various therapies directed at modulating neuroinflammation [34, 35], Thus, it is possible that the beneficial effects observed with RIPK1 inhibition in Npc1 mutant mice is due more to its involvement in the innate immune response rather than as a mediator of necroptosis.

The data presented in this paper, combined with our previous work on RIPK1 inhibition [15], clearly demonstrates that RIPK1 plays a role in the NPC1 pathological cascade. It is tempting to speculate that the marked phenotypic differences observed between Npc1 mutant mice on C57B1/6 and Balb/c backgrounds [36] might be influenced by well-known differences in background-mediated immune responses that involve RIPK1 [37-39]. Independent of the exact pathological role that RIPK1 mediates in NPC1, it is clear that inhibition of RIPK1 may play a role as one component in a combination therapy of NPC1.

Acknowledgements and funding

AC, AS, and FDP funding were supported by the intramural research program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by a Bench-to-Bedside award from the NIH Clinical Center and the NIH Office of Rare Diseases. AC and FDP received funding from the Ara Parseghian Medical Research foundation. SC was supported by Dana’s Angels Research Trust. SLM and JB are GlaxoSmithKline employees. The Ripk3−/− mice were provided by Dr. V. Dixit (Genentech). GSK’547 and the Ripk1kd/kd mice were provided by GlaxoSmithKline.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. SN and JB are employed by GlaxoSmithKline.

References

- [1].Pentchev PG, Comly ME, Kruth HS, Vanier MT, Wenger DA, Patel S, Brady RO, A defect in cholesterol esterification in Niemann-Pick disease (type C) patients Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82 (1985) 8247–8251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Camargo F, Erickson RP, Garver WS, Hossain GS, Carbone PN, Heidenreich RA, Blanchard J, Cyclodextrins in the treatment of a mouse model of Niemann-Pick C disease Life Sci 70 (2001) 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Runz H, Dolle D, Schlitter AM, Zschocke J, NPC-db, a Niemann-Pick type C disease gene variation database Hum Mutat 29 (2008) 345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vanier MT, Niemann-Pick disease type C Orphanet J Rare Dis 5 (2010) 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yanjanin NM, Velez JI, Gropman A, King K, Bianconi SE, Conley SK, Brewer CC, Solomon B, Pavan WJ, Arcos-Burgos M, Patterson MC, Porter FD, Linear clinical progression, independent of age of onset, in Niemann-Pick disease, type C Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 153B (2010) 132–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Geberhiwot T, Moro A, Dardis A, Ramaswami U, Sirrs S, Marfa MP, Vanier MT, Walterfang M, Bolton S, Dawson C, Heron B, Stampfer M, Imrie J, Hendriksz C, Gissen P, Crushell E, Coll MJ, Nadjar Y, Klunemann H, Mengel E, Hrebicek M, Jones SA, Ory D, Bembi B, Patterson M, International Niemann-Pick Disease R, Consensus clinical management guidelines for Niemann-Pick disease type C Orphanet J Rare Dis 13 (2018) 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wassif CA, Cross JL, Iben J, Sanchez-Pulido L, Cougnoux A, Platt FM, Ory DS, Ponting CP, Bailey-Wilson JE, Biesecker LG, Porter FD, High incidence of unrecognized visceral/neurological late-onset Niemann-Pick disease, type C1, predicted by analysis of massively parallel sequencing data sets Genet Med 18 (2016) 41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pineda M, Walterfang M, Patterson MC, Miglustat in Niemann-Pick disease type C patients: a review Orphanet J Rare Dis 13 (2018) 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Patterson MC, Vecchio D, Prady H, Abel L, Wraith JE, Miglustat for treatment of Niemann-Pick C disease: a randomised controlled study Lancet Neurol 6 (2007) 765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ory DS, Ottinger EA, Farhat NY, King KA, Jiang X, Weissfeld L, Berry-Kravis E, Davidson CD, Bianconi S, Keener LA, Rao R, Soldatos A, Sidhu R, Walters KA, Xu X, Thurm A, Solomon B, Pavan WJ, Machielse BN, Kao M, Silber SA, McKew JC, Brewer CC, Vite CH, Walkley SU, Austin CP, Porter FD, Intrathecal 2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin decreases neurological disease progression in Niemann-Pick disease, type C1: a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1-2 trial Lancet 390 (2017) 1758–1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hitomi J, Christofferson DE, Ng A, Yao J, Degterev A, Xavier RJ, Yuan J, Identification of a molecular signaling network that regulates a cellular necrotic cell death pathway Cell 135 (2008) 1311–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Christofferson DE, Yuan J, Necroptosis as an alternative form of programmed cell death Curr Opin Cell Biol 22 (2010) 263–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Chan FK, Kroemer G, Necroptosis: Mechanisms and Relevance to Disease Annu Rev Pathol 12 (2017) 103–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vitner EB, Salomon R, Farfel-Becker T, Meshcheriakova A, Ali M, Klein AD, Platt FM, Cox TM, Futerman AH, RIPK3 as a potential therapeutic target for Gaucher's disease Nat Med 20 (2014) 204–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cougnoux A, Cluzeau C, Mitra S, Li R, Williams I, Burkert K, Xu X, Wassif CA, Zheng W, Porter FD, Necroptosis in Niemann-Pick disease, type C1: a potential therapeutic target Cell Death Dis 7 (2016) e2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Degterev A, Maki JL, Yuan J, Activity and specificity of necrostatin-1, small-molecule inhibitor of RIP1 kinase Cell Death Differ 20 (2013) 366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Berger SB, Kasparcova V, Hoffman S, Swift B, Dare L, Schaeffer M, Capriotti C, Cook M, Finger J, Hughes-Earle A, Harris PA, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES, Bertin J, Gough PJ, Cutting Edge: RIP1 kinase activity is dispensable for normal development but is a key regulator of inflammation in SHARPIN-deficient mice J Immunol 192 (2014) 5476–5480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Loftus SK, Morris JA, Carstea ED, Gu JZ, Cummings C, Brown A, Ellison J, Ohno K, Rosenfeld MA, Tagle DA, Pentchev PG, Pavan WJ, Murine model of Niemann-Pick C disease: mutation in a cholesterol homeostasis gene Science 277 (1997) 232–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Newton K, Sun X, Dixit VM, Kinase RIP3 is dispensable for normal NF-kappa Bs, signaling by the B-cell and T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 Mol Cell Biol 24 (2004) 1464–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Peterson LW, Philip NH, DeLaney A, Wynosky-Dolfi MA, Asklof K, Gray F, Choa R, Bjanes E, Buza EL, Hu B, Dillon CP, Green DR, Berger SB, Gough PJ, Bertin J, Brodsky IE, RIPK1-dependent apoptosis bypasses pathogen blockade of innate signaling to promote immune defense J Exp Med 214 (2017) 3171–3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Collins TJ, ImageJ for microscopy Biotechniques 43 (2007) 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bullova P, Cougnoux A, Abunimer L, Kopacek J, Pastorekova S, Pacak K, Hypoxia potentiates the cytotoxic effect of piperlongumine in pheochromocytoma models Oncotarget 7 (2016) 40531–40545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Williams IM, Wallom KL, Smith DA, Al Eisa N, Smith C, Platt FM, Improved neuroprotection using miglustat, curcumin and ibuprofen as a triple combination therapy in Niemann-Pick disease type C1 mice Neurobiol Dis 67 (2014) 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Davidson CD, Ali NF, Micsenyi MC, Stephney G, Renault S, Dobrenis K, Ory DS, Vanier MT, Walkley SU, Chronic cyclodextrin treatment of murine Niemann-Pick C disease ameliorates neuronal cholesterol and glycosphingolipid storage and disease progression PLoS One 4 (2009) e6951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liu B, Li H, Repa JJ, Turley SD, Dietschy JM, Genetic variations and treatments that affect the lifespan of the NPC1 mouse J Lipid Res 49 (2008) 663–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Liu B, Turley SD, Burns DK, Miller AM, Repa JJ, Dietschy JM, Reversal of defective lysosomal transport in NPC disease ameliorates liver dysfunction and neurodegeneration in the npc1−/− mouse Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 (2009) 2377–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kelliher MA, Grimm S, Ishida Y, Kuo F, Stanger BZ, Leder P, The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kappaB signal Immunity 8 (1998) 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vite CH, Bagel JH, Swain GP, Prociuk M, Sikora TU, Stein VM, O'Donnell P, Ruane T, Ward S, Crooks A, Li S, Mauldin E, Stellar S, De Meulder M, Kao ML, Ory DS, Davidson C, Vanier MT, Walkley SU, Intracisternal cyclodextrin prevents cerebellar dysfunction and Purkinje cell death in feline Niemann-Pick type C1 disease Sci Transl Med 7 (2015) 276ra226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yuan J, Kroemer G, Alternative cell death mechanisms in development and beyond Genes Dev 24 (2010) 2592–2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Erickson RP, Bernard O, Studies on neuronal death in the mouse model of Niemann-Pick C disease J Neurosci Res 68 (2002) 738–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Berger SB, Bertin J, Gough PJ, Life after death: RIP1 and RIP3 move beyond necroptosis Cell Death Discov 2 (2016) 16056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Christofferson DE, Li Y, Hitomi J, Zhou W, Upperman C, Zhu H, Gerber SA, Gygi S, Yuan J, A novel role for RIP1 kinase in mediating TNFalpha production Cell Death Dis 3 (2012) e320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Suzuki M, Sugimoto Y, Ohsaki Y, Ueno M, Kato S, Kitamura Y, Hosokawa H, Davies JP, Ioannou YA, Vanier MT, Ohno K, Ninomiya H, Endosomal accumulation of Toll-like receptor 4 causes constitutive secretion of cytokines and activation of signal transducers and activators of transcription in Niemann-Pick disease type C (NPC) fibroblasts: a potential basis for glial cell activation in the NPC brain J Neurosci 27 (2007) 1879–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cougnoux A, Drummond RA, Collar AL, Iben JR, Salman A, Westgarth H, Wassif CA, Cawley NX, Farhat NY, Ozato K, Lionakis MS, Porter FD, Microglia activation in Niemann-Pick disease, type C1 is amendable to therapeutic intervention Hum Mol Genet 27 (2018) 2076–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Smith D, Wallom KL, Williams IM, Jeyakumar M, Platt FM, Beneficial effects of anti-inflammatory therapy in a mouse model of Niemann-Pick disease type C1 Neurobiol Dis 36 (2009) 242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Parra J, Klein AD, Castro J, Morales MG, Mosqueira M, Valencia I, Cortes V, Rigotti A, Zanlungo S, Npc1 deficiency in the C57BL/6J genetic background enhances Niemann-Pick disease type C spleen pathology Biochem Biophys Res Commun 413 (2011) 400–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Watanabe H, Numata K, Ito T, Takagi K, Matsukawa A, Innate immune response in Th1- and Th2-dominant mouse strains Shock 22 (2004) 460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Geiger SM, Abrahams-Sandi E, Soboslay PT, Hoffmann WH, Pfaff AW, Graeff-Teixeira C, Schulz-Key H, Cellular immune responses and cytokine production in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice during the acute phase of Angiostrongylus costaricensis infection Acta Trop 80 (2001) 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sellers RS, Clifford CB, Treuting PM, Brayton C, Immunological variation between inbred laboratory mouse strains: points to consider in phenotyping genetically immunomodified mice Vet Pathol 49 (2012) 32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]