Summary

Previous studies reported increased eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) incidence in children. It is unclear whether this reported increased EoE incidence is true or due to increased recognition and diagnostic endoscopy among children. A population-based study that evaluated EoE incidence in OC, Minnesota, from 1976 to 2005 concluded that EoE incidence increased significantly over the past three 5-year intervals (from 0.35 [range: 0–0.87] per 100,000 person-years for 1991–1995 to 9.45 [range: 7.13–11.77] per 100,000 person-years for 2001–2005). The aim of this study is to assess the change of incidence and characteristics of EoE in children in the same population between 2005 and 2015 and compare the findings to those reported in the previous study. We retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical records from Olmsted Medical Center and Mayo Clinic between 2005 and 2015, using Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) resources. All children with EoE diagnosis based on the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) guidelines were included. The incidence and characteristics of children with EoE during the study period were compared to those diagnosed between 1995 and 2005. The incidence of EoE in children adjusted for age and sex was 5.31 per 100,000 population person-years in 1995, 15.2 in 2005, and 19.2 in 2015. Change in annual incidence and seasonal variation were not significant, (P = .48) and (P = .32), respectively. Between 2005 and 2015, 73 children received an EoE diagnosis (boys 49; 67%) compared to 16 children (boys 10; 62.5) between 1995 and 2005. Mean (SD) age at diagnosis was 7.5 (5.2) and 12.8 (4.3) years, respectively. Symptoms differed by age of presentation, with vomiting the most common in children younger than 5 years (41.1% and 43.5%) and dysphagia in those older than 5 years (35.6% and 60.9%). The incidence of EoE was not increased for any specific age-group during the study period (P = .49). This study showed increased incidence of EoE in children in Olmsted County between 2005 and 2015 compared to the incidence between 1995 and 2005 (5.31 per 100,000 population person-years in 1995, 15.2 in 2005, and 19.2 in 2015). However, between 2005 and 2015, the change of incidence was not statically significant, (P = .48) despite the steady increase of EGD performed during the same time frame (64 in 2005 to 144 in 2015). By comparing children diagnosed between 2005 and 2015 to those diagnosed between 1995 and 2005, the mean age at diagnosis was younger in the former group, 7.5 versus 12.8 years. Vomiting replaced dysphagia as the most common clinical presentation. Otherwise, the presenting symptom of EoE in children remained consistent across specific age groups.

Keywords: children, eosinophilic esophagitis, epidemiology, incidence, pediatrics

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune- and antigen-mediated esophageal disease characterized by eosinophil-predominant inflammation of the esophagus.1 EoE was first reported by Attwood et al.2 Publications reported an increased in EoE incidence among all age groups in the majority of US states.3 Epidemiologic studies have reported increased incidence and prevalence of EoE in children.4,5 A systematic review and meta-analysis of the epidemiologic factors of EoE in children worldwide reported an incidence of 0.7 to 10.0 per 100,000 person-years and a prevalence range of 0.2 to 43.0 per 100,000 person-years.6 It is unclear whether this reported increased EoE incidence is true or due to increased recognition and diagnostic endoscopy among children.

A strong association between EoE and other allergic conditions, such as asthma, eczema, environmental allergy, and food allergy has been reported.7–9 Studies suggested that other atopic and allergic disorders have been also increasing in incidence.10,11

A population-based study that evaluated EoE incidence in OC, Minnesota, from 1976 to 2005 identified 78 patients, including 23 children.12 The investigators concluded that EoE incidence increased significantly over the past three 5-year intervals (from 0.35 [range: 0–0.87] per 100,000 person-years for 1991–1995 to 9.45 [range: 7.13–11.77] per 100,000 person-years for 2001–2005). Other studies from Europe have reported similar trend in increasing incidence of EoE.13,14 It is not known whether the factors that caused the recognition and the increased incidence of EoE in the Western population are still increasing or have reached a steady state. We aimed to assess the incidence trend and characteristics of EoE among children in the past decade in OC, Minnesota, and compare them to those between 1995 and 2005.

METHODS

Clinical setting

This retrospective study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center (OMC) institutional review boards. OC is located in southeastern Minnesota. It has the same age, sex, and ethnic characteristics of Minnesota in general, with a majority of non-Hispanic whites (82%) and small minorities of African American (6%), Asian (6%), Hispanic (5%), and mixed ethnicities.15 Residents of OC receive their medical care at two medical centers: Mayo Clinic and OMC. The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) is a distinctive research infrastructure system that links medical records of OC residents for approved medical research. This infrastructure helps conduct population-based, descriptive, case-control, historical, and prospective cohort and cross-sectional studies of most diseases and medical conditions.16

Eligibility criteria and search strategies

For this study, cases were identified using the REP database. The terms eosinophilic esophagitis, esophageal eosinophilia, EoE, and EE were used to identify patients. A separate search of Mayo Clinic records was conducted using the Advanced Cohort Explorer software. Results were cross-matched for accuracy and complete identification of cases. The definition of EoE was on the basis of the 2013 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) guidelines.17,18

All children had gastrointestinal symptoms and continued to have symptoms despite receiving proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy for 2 months. All children in this study underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with triple site biopsies from the stomach, duodenum, and 4 to 6 esophageal biopsies obtained from at least 2 different levels of the esophagus. The mucosal eosinophilia was isolated to the esophagus. Cases that did not meet these criteria were excluded. The study included only children <18 years who were residing in OC for at least 1 year before their EoE diagnoses. The identified cases underwent an extensive chart review by two investigators (S.H. and Y.H.) to confirm the diagnosis and collect relevant data; including demographic characteristic; associated allergic conditions, family history of EoE, gastroesophageal reflux disorder, and allergic conditions; endoscopic and; histopathologic findings; medical therapy (PPI, topical glucocorticosteroids, 6-food elimination diet, targeted food elimination diet, or elemental formula diet, or a combination) and response to therapy (no change, improvement, or resolution of symptoms).

A separate search was conducted about the total number of EGD examinations performed for children who resided in OC from January 1, 2005, through December 31, 2015, at the time of the EGD. Mayo Clinic is the only center in OC at which children undergo EGD, and all children in this study had their EGD done at Mayo Clinic.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are summarized as mean (standard deviation [SD]); categorical variables are presented as frequency (percentage). Incidence rates are reported as number of cases per 100,000 person-years, using the OC population (age <18 years) as the population at risk.19 Age- and sex-adjusted rates were adjusted according to counts from the population according to the 2010 US census. Multivariable Poisson regression models were used to assess the association of age, sex, and calendar year with the incidence of EoE diagnoses, using the log of the population as an offset variable. Seasonal variation in the incidence of EoE diagnoses was tested with the Rayleigh test, which evaluates whether a circular distribution has uniform probabilities.20 Data were analyzed with statistical software (SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc). A type I error rate of 0.05 was used for all confidence intervals (CIs) and hypothesis tests.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of identified children with EoE

In total, 73 children received a new diagnosis of EoE in OC between 2005 and 2015 (Table 1). Of these children, 49 (67.1%) were boys. Mean (SD) age at diagnosis was 7.5 (5.2) years. At the time of diagnosis, 31 children were aged ≤5 years, 30 were aged 6 to 14 years, and 12 were aged 15 to 17 years. Vomiting was the most common presentation (n = 30, 41.1%) by dysphagia (n = 26, 35.6%), abdominal pain (n = 19 26.0%), food impaction (n = 7, 9.6%), failure to thrive (n = 6, 8.2%), and hematemesis (1, 1.4%). Symptoms differed by age at presentation. Vomiting was the most common symptom for children aged <5 years (77.7%); dysphagia was the most common for children 5 to 17 years of age (47.8%). Twenty-nine children had asthma (39.7%), 18 (24.7%) had eczema, 45 (61.6%) had allergic rhinitis, and 35 (47.9%) had food allergy. Only two children (2.7%) had a family history of EoE.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics and endoscopic and histologic findings.

| Variable | Overall (N = 16) 1995–2005 | Overall (N = 73) 2005–2015 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at diagnosis (SD) | 10 (6) | 7.5 (5.2) | 0.64 |

| Male, No. (%) | 10 (62.5%) | 49 (67.1%) | 0.87 |

| Presenting symptom | |||

| Vomiting | 6 (43.5%) | 30 (41.1%) | 0.84 |

| Dysphagia | 10 (60.9%) | 26 (35.6%) | 0.032 |

| Abdominal pain | 5 (30.4%) | 19 (26.0%) | 0.68 |

| Food impaction | 3 (21.7%) | 7 (9.6%) | 0.12 |

| Failure to thrive | Unavailable data | 6 (8.2%) | |

| Duration of symptoms Mean (month) | Unavailable data | 13 | |

| History of asthma | 7/11 (63.6%) | 29 (39.7%) | 0.14 |

| Data available on 11 children | |||

| History of eczema | Unavailable data | 18 (24.7%) | |

| History of allergic rhinitis | 7/13 (53.8%) | 45 (61.6%) | 0.60 |

| Data available on 13 children | |||

| History of food allergy | 8/14 (57.1%) | 35 (47.9%) | 0.53 |

| Data available on 14 children | |||

| Family history of EoE | 6 (37.5%) | 2 (2.7%) | <0.001 |

| Esophageal endoscopic findings | |||

| Normal | 10 (65.2%) | 16 (21.9%) | <0.001 |

| Linear furrows | 5 (30.4%) | 58 (79.5%) | <0.001 |

| White plaques | 0 (0%) | 31 (42.5%) | <0.001 |

| Trachealization | 1 (<1%) | 5 (6.8%) | 0.67 |

| Stricture | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – |

| Mean eosinophil count/HPF on esophageal biopsies | 0.20 | ||

| 15–30 | 7 (39.2%) | 33 (45.2%) | |

| 31–45 | 4 (26%) | 8 (11.0%) | |

| >45 | 5 (34.8%) | 32 (43.8%) |

Between 1995 and 2005 that included 16 children received a diagnosis of EoE (10 boys; 62.5%), with a mean age of diagnosis of 12.8 (4.3) years. The most common presentations were dysphagia (n = 10, 60.9%), vomiting (n = 7, 43.5%) and abdominal pain (n = 5, 30.4%). At the time of diagnosis, 2 children were aged ≤5 years, 6 were aged 6 to 14 years, and 8 were aged 15 to 17 years. Symptoms also varied by age at presentation with vomiting as the clinical presentation in children aged <5 years and dysphagia the most common presentation for children 5 to 17 years of age (60.9%).

Associated allergic conditions were not available on all patients, however included asthma in 7 out of 11 (63.6%), food allergies in 8/14 (57.1%) and seasonal allergies in 7 out of 13 (53.8%).

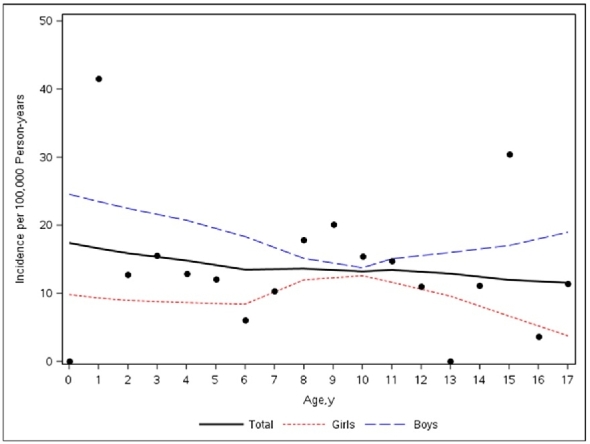

Temporal trend of incidence

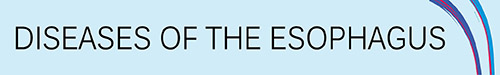

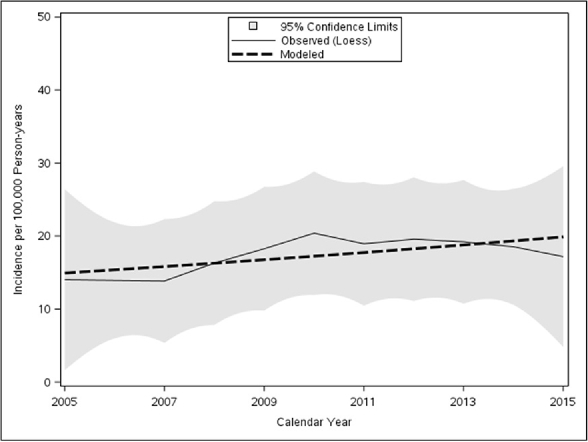

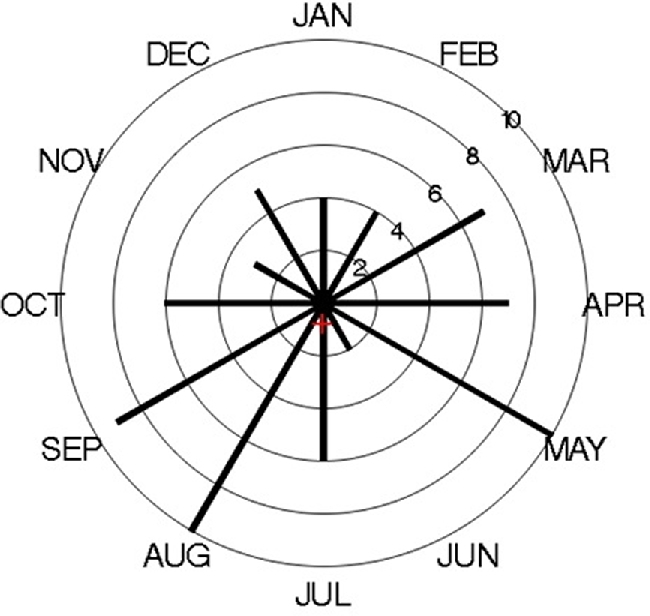

The overall annual age- and sex-adjusted standardized incidence rate of EoE in 2005 was 15.2 (95% CI, 2.9–27.9) per 100,000 person-years. This rate peaked at 25.1 (95% CI, 9.41–40.84) per 100,000 person-years in 2013, then decreased to19.2 (95% CI, 4.89–33.46) in 2015. The change in annual incidence was not statistically significant (P = .48) (Fig. 1). When their data were added to a Poisson model, including sex, age, and age of diagnosis, boys were significantly more likely to have EoE than girls (relative risk [RR] [95% CI], 1.95 [1.20–3.18]; P = .007), whereas age (RR [95% CI], 0.98 [0.94–1.02]; P = .49) and year of diagnosis (RR [95% CI], 1.03 [0.95–1.10]; P = .37) were not significantly associated (Fig. 2). Although cases were diagnosed more frequently in May, August, and September, seasonal variation was not statistically significant (P = .32) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Loess smooth of incidence of EoE in children and shaded 95% confidence limits with modeled linear trend as dashed line.

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot of the total number of incident cases versus age with the loess smooth of total cases stratified by sex.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of month of diagnosis of incident cases of EoE in Olmsted County, MN from 2005 to 2015 (The red cross indicates the mean vector of the distribution).

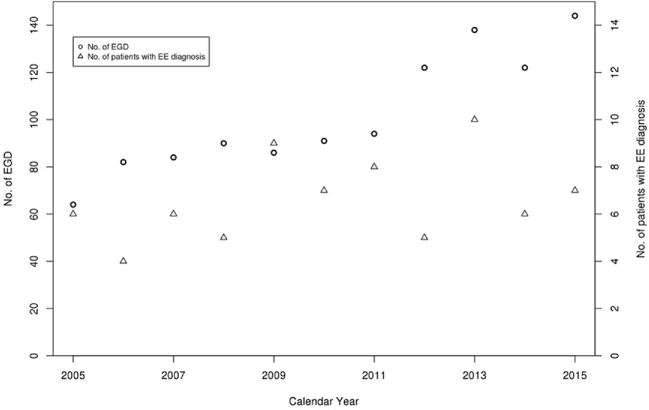

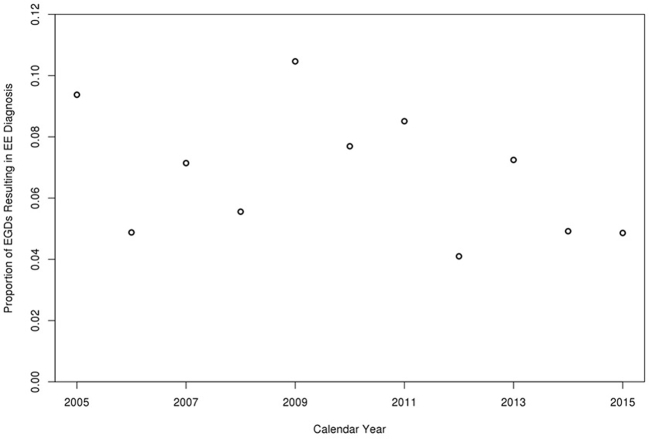

In children diagnosed with EoE between 1995 and 2005, The overall annual age- and sex-adjusted standardized incidence rate of EoE was 5.31 (95% CI: 2.85, 7.78) per 100,000 population per year (Fig. 4). The change of incidence was not statistically significant despite the increased number of EGD volume over the same period, which steadily increased from 64 in 2005 to 144 in 2015 (Figs 5,6).

Fig. 4.

Incidence of EoE in children in Olmsted County, MN over 3 year intervals (1995–2015).

Fig. 5.

Secular trends in endoscopy volume and number of EoE cases diagnosed per year.

Fig. 6.

Proportion of EGDs resulting in EoE diagnosis per calendar year.

Endoscopic and histologic findings in children with EoE

In children diagnosed with EoE between 2005 and 2015, EGD was grossly normal for 16 children (21.9%) of whom, 10 were <5 years of age. Abnormal esophageal endoscopic findings included linear furrows of 58 children (79.5%), white plaques of 31 (42.5%), and trachealization of 5 (6.8%). Thirty-one children had >1 abnormal esophageal endoscopic finding (i.e. linear furrows and white plaques). None of these children had an esophageal stricture, which was defined as any endoscopic description of narrowing in the esophagus (Table 1). Thirty nine patients had an esophagram, which was normal in all patients except for a 14-year-old male who had a mildly narrowed esophagus throughout its course.

Thirty-three children (45.2%) had between 15 and 30 eosinophils per high-power field (Eos/HPF) on the biopsies, 8 (11.6%) had between 31 and 45 Eos/HPF, and 32 (43.8%) had >45 Eos/HPF (Table 1). These values were off therapy other than PPI.

Between 1995 and 2005, out of the 16 children, 10 (65.2%) had normal endoscopic appearance of the esophagus, of whom 2 (20%) were <5 years of age (Table 1). Abnormal esophageal endoscopic findings included linear furrows in 5 (30.4%), trachealization in 1(<1%), and no esophageal stricture. Seven children (39.1%) had (15–30) eosinophils per high-power field (Eos/HPF) on the biopsies, 4 (26%) had (30–45) Eos/HPF and 4 (34.8%) had >45 Eos/HPF.

Outcome and response to therapy of children with EoE

The management of EoE in children varied between providers, which reflected the variable treatment approaches. Children were offered the option of elimination diet or topical steroid.

In children diagnosed with EoE between 2005 and 2015, all children received PPI therapy. Twenty nine children received topical glucocorticosteroid and started a targeted food elimination diet in those with positive food allergy skin prick. Forty two children received topical glucocorticosteroid, 1 child began a 6-food elimination diet; 1 patient started an elemental diet.

Children's response to treatment was assessed in all included children, 18 (24.7%) reported symptom resolution; 51 (69.9%), improvement in symptoms; and 4 (5.5%), no change in symptoms. Of the children who reported no change in symptoms, 3 underwent repeat EGD; in which 1 child was found to have persistence of EoE and 2 had normal esophageal biopsies. However, 1 child had duodenitis based on histopathologic findings, and 1 had reported improvement in symptoms after increasing the dose of omeprazole to 20 mg twice daily. A fourth child who reported no improvement in symptoms was lost to follow-up and did not undergo repeat EGD. Of the 51 children who reported symptom improvement, 42 underwent repeat EGD because of symptom recurrence. Repeat EGD was performed 2 month to 3 years after the initial EGD. Twenty-seven children (64.3%) had endoscopic findings (linear furrows, white plaques, or esophageal stricture, or a combination) on repeat EGD, suggestive of EoE recurrence. Of the 42 children who underwent repeat EGD, 23 (55%) were on treatment, of whom, 10 had a normal appearing repeat EGD.

Forty three children (58.9%) underwent a repeat EGD. Mean (SD) time between the initial and the repeat EGDs was 11 (13) months. The repeat EGD was grossly normal in 16 (37.2%) children, 5 of whom had a grossly normal initial EGD. Abnormal findings included linear furrows in 28 children (65.1%) and white plaques in 9 (20.9%). None of the repeated EGDs showed trachealization or esophageal strictures. Twenty children (46.5%) had ≤15 Eos/HPF, 9 (20.9%) had 15 to 30 Eos/HPF on esophageal biopsies, 3 (7.0%) had 31 to 45 Eos/HPF, and 11 (25.6%) had >45 Eos/HPF. Of the entire cohort, 14 patients underwent repeat EGD after 2 months of therapy to document remission regardless of their symptoms and of those, 12 (86%) had <15 Eos/HPF on esophageal biopsies. On the other hand, 30 patients underwent repeat EGD after an average of 13 months (range: 3–36 months) due to symptoms recurrence. Out of 30 patients 21 (70%) had >15 Eos/HPF on repeat esophageal biopsies.

In children diagnosed with EoE between 1995 and 2005, 14 children received PPI therapy as well as topical glucocorticosteroids and two patients lost to follow-up. None of these children was started on elimination diet. Six children (37.5%) reported symptom resolution and 6 (37.5%) children reported improvement in symptoms. In children who reported resolution or improvement in their symptoms, 11 underwent repeat EGD after an average of 25 months (range: 2–49 months). The repeat EGD was grossly normal in 6 (54.5%) children, of whom 4 had a grossly normal initial EGD. Abnormal findings included linear furrows in 5 (45.5%) children and white plaques in 4 (36.3%). None of the repeated EGDs showed trachealization or esophageal strictures. Three children (27.2%) had 15 to 30 Eos/HPF on esophageal biopsies, 2 (18.1%) had 31 to 45 Eos/HPF, and 1 (9.09%) had >45 Eos/HPF.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report the change of EoE incidence and characteristics in children in OC from 2005 through 2015, as well as the demographic characteristics of children with a diagnosis of EoE and their response to medical therapy. We compared the results to those obtained on children diagnosed with EoE between 1995 and 2005. We concluded that the overall annual incidence of EoE increased over these two decades but did not increase between 2005 and 2015 despite the increase in endoscopy volume over the same period, which steadily increased from 64 in 2005 to 144 in 2015 (Figs 5,6). Boys were significantly more likely than girls to have EoE. In our cohort, the different clinical presentation by age was similar to what had been reported previously in other studies.21,22

The incidence of EoE between 2005 and 2015 was higher than that between 1995 and 2005, however during the period between 2005 and 2015 the change of incidence was not statistically significant. Increased recognition might have affected the change in incidence. PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia was not a separate entity from EoE, and inclusion of the patients with PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia in previous epidemiology studies might have contributed to the reported increase in incidence.13,14,23 The change of practice in terms of obtaining esophageal biopsies from two different levels, number of biopsies obtained and not obtaining esophageal biopsies from a normal appearing esophagus might have affected the number of diagnosed cases. Currently, obtaining at least 4 esophageal biopsies from two different levels is recommended.24-26

Studies had different results for seasonal variations in the detection and diagnosis of EoE.27–31 In our study, more cases were diagnosed during May, August, and September; however this seasonal variation was not statistically significant, which consistent with the previous finding by Elias et al that showed no seasonal concentration in the diagnosis of esophageal eosinophilia.29 The year-round diagnosis of EoE could be explained by the factors reported as causes, such as food allergy, environmental allergy, and genetics. In addition, the month of diagnosis may not reflect disease activity. A lag could be present between onset of histologic changes in the esophagus, symptoms development, and the diagnosis, which is supported by the progressive nature of the condition.32 In our cohort, children had symptoms for 399.3 (417.6) days before the diagnosis of EoE.

EoE was more frequently diagnosed in boys (67%) (P = .007). The predominance of EoE in male patients, the association with atopic conditions, and the seasonal variation suggest genetic predisposition with triggering environmental factors.33,34

Most children had endoscopic findings suggestive of EoE, such as linear furrows and white plaques. About 21% of children had a normal-appearing esophagus despite having symptoms and abnormal biopsies suggestive of EoE, a fact that reinforces the importance of obtaining biopsies regardless of endoscopic appearance.26 The prevalence of reported abnormal esophageal endoscopic findings (linear furrows and white plaques) has also increased, which can be explained by increased recognition and awareness of EoE and its endoscopic findings. Most children reported improvement in their symptoms; however, among children who underwent repeat EGD, >50% had endoscopic and histopathologic findings suggestive of EoE, which support the modest accuracy of symptoms alone in predicting endoscopic and histologic remission of EoE.35

The rate of esophageal eosinophilia on repeat EGDs was higher in those who underwent repeat EGD due to recurrence of symptoms when compared to those who underwent repeat EGD to document remission after 2 months. The finding of higher rate EoE recurrence in the latter group is more like a result of discontinuation or nonadherence to therapy due to symptoms resolution/improvement.

By comparing children diagnosed between 2005 and 2015 to those diagnosed between 1995 and 2005, mean age at diagnosis was younger in the former group, 7.5 versus 12.8 years. This can be explained by early recognition or alteration in the pathogenesis of the condition making children more prone to acquiring the disease. In both groups, there was a male predominance suggesting genetic role as a contributing factor. Vomiting replaced dysphagia as the most common clinical presentation, which can be explained by younger age at diagnosis or early recognition and management that leads to delay or cessation in the progression of the disease. Otherwise, the presenting symptom of EoE in children remained consistent across specific age groups.

Limitations of the study include its retrospective nature, the small number of cases, and the demographic characteristics of OC, where >80% of the population were white. Only 59% of children with EoE underwent a repeat EGD, which made it difficult to document the endoscopic and histologic resolution of EoE in children with the condition. However, the present study was population-based research with epidemiologic advantages for retrospective population-based studies, including a self-contained health care environment and a medical record linkage system through the REP for almost the entire OC population.

Acknowledgment

This study was made possible using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG034676. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Notes

Specific author contributions: Collected data: Salim Hommeida, Yamen Hafed; Drafted the initial manuscript: Salim Hommeida; Approved the final manuscript as submitted: Salim Hommeida, Rayna M. Grothe, Yamen Hafed, Ryan J. Lennon, Cathy D. Schleck, Jeffrey A. Alexander, David A. Katzka, Imad Absah; Reviewed and revised the manuscript: Rayna M. Grothe, Jeffrey A. Alexander, David A. Katzka, Imad Absah; Performed the statistical analysis: Ryan J. Lennon, Cathy D. Schleck; Designed the study protocol: Imad Absah.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding: N/A.

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center, Rochester, Minnesota, institutional review boards.

References

- 1. Furuta G T. Eosinophilic esophagitis: update on clinicopathological manifestations and pathophysiology. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2011; 27: 383–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Attwood S E, Smyrk T C, Demeester T R, Jones J B. Esophageal eosinophilia with dysphagia. Digest Dis Sci 1993; 38: 109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kapel R C, Miller J K, Torres C, Aksoy S, Lash R, Katzka D A. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a prevalent disease in the United States that affects all age groups. Gastroenterology 2008; 134: 1316–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Erwin E A, Asti L, Hemming T, Kelleher K J. A decade of hospital discharges related to eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012; 54: 427–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Straumann A, Simon H U. Eosinophilic esophagitis: escalating epidemiology? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005; 115: 418–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Soon I S, Butzner J D, Kaplan G G, deBruyn J C. Incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013; 57: 72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Spergel J M, Beausoleil J L, Mascarenhas M, Liacouras C A. The use of skin prick tests and patch tests to identify causative foods in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002; 109: 363–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Henderson C J, Abonia J P, King E C et al. Comparative dietary therapy effectiveness in remission of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129: 1570–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roy-Ghanta S, Larosa D F, Katzka D A. Atopic characteristics of adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6: 531–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moorman J E, Rudd R A, Johnson C A et al. National surveillance for asthma–United States, 1980–2004. MMWR Surveill Summ 2007; 56: 1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yawn B P, Wollan P, Kurland M, Scanlon P.. A longitudinal study of the prevalence of asthma in a community population of school-age children. J Pediatr 2002; 140: 576–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Prasad G A, Alexander J A, Schleck C D et al. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis over three decades in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 1055–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Straumann A, Simon H U. Eosinophilic esophagitis: escalating epidemiology? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005; 115: 418–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hruz P, Straumann A, Bussmann C et al. Escalating incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis: a 20-year prospective, population-based study in Olten County, Switzerland. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128: 1349–1350.e5, e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. St Sauver J L, Grossardt B R, Leibson C L, Yawn B P, Melton L J 3rd, Rocca W A. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc 2012; 87: 151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rocca W A, Yawn B P, St Sauver J L, Grossardt B R, Melton L J 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc 2012; 87: 1202–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dellon E S, Gonsalves N, Hirano I et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 679–92;quiz 93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Furuta G T, Liacouras C A, Collins M H et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology 2007; 133: 1342–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. St Sauver JL G B, Yawn B P, Melton L J 3rd, Rocca W A. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Am J Epidemiol 2011; 173: 1059–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Batschelet E. Circular Statistics in Biology, London: Academic Press, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baxi S, Gupta S K, Swigonski N, Fitzgerald J F. Clinical presentation of patients with eosinophilic inflammation of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 64: 473–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liacouras C A, Spergel J M, Ruchelli E et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a 10-year experience in 381 children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 3: 1198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arias Á, Pérez-Martínez I, Tenías J M, Lucendo A J. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults in population-based studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 43: 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Collins M H. Histopathologic features of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2008; 18: 59–71; viii-ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nielsen J A, Lager D J, Lewin M, Rendon G, Roberts C A. The optimal number of biopsy fragments to establish a morphologic diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 515–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim H P, Vance R B, Shaheen N J, Dellon E S. The prevalence and diagnostic utility of endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10: 988–996.e5.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Onbasi K, Sin A Z, Doganavsargil B, Onder G F, Bor S, Sebik F. Eosinophil infiltration of the oesophageal mucosa in patients with pollen allergy during the season. Clin Exp Allergy 2005; 35: 1423–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang F Y, Gupta S K, Fitzgerald J F. Is there a seasonal variation in the incidence or intensity of allergic eosinophilic esophagitis in newly diagnosed children? J Clin Gastroenterol 2007; 41: 451–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elias M K, Kopacova J, Arora A S et al. The diagnosis of esophageal eosinophilia is not increased in the summer months. Dysphagia 2015; 30: 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lucendo A J, Arias Á, Redondo-González O, González-Cervera J. Seasonal distribution of initial diagnosis and clinical recrudescence of eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2015; 70: 1640–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jensen E T, Shah N D, Hoffman K, Sonnenberg A, Genta R M, Dellon E S. Seasonal variation in detection of oesophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 461–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. DeBrosse C W, Franciosi J P, King E C et al. Long-term outcomes in pediatric-onset esophageal eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128: 132–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Abonia J P, Wen T, Stucke E M et al. High prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with inherited connective tissue disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132: 378–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Antico A, Fante R. Esophageal hypereosinophilia induced by grass sublingual immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 133: 1482–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Safroneeva E, Straumann A, Coslovsky M et al. Symptoms have modest accuracy in detecting endoscopic and histologic remission in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 581–590.e4.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]