Abstract

A 47-year-old male who previously underwent coronary bypass graft surgery was transferred to our hospital for treatment of bare metal in-stent restenosis (ISR) of severely calcified left main (LM) coronary lesion. During a repeat coronary intervention, LM coronary perforation occurred after rotational atherectomy followed by balloon dilatation. Hemostasis was successfully achieved by implantation of a single polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered stent. Although intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) were documented, any additional information was not obtained except stent expansion. Routine 6-month follow-up angiography revealed no findings of restenosis. Three representative imaging modalities, IVUS, OCT, and angioscopy were applied to visualize and differentiate any structures within the PTFE-covered stent. Intravascular findings included, (1) vascular structures outside the covered stent could be observed sufficiently by both IVUS and OCT at this time that could not be seen at all just after implantation, (2) neointimal hyperplasia distributed dominantly at both stent edges, and (3) in-stent micro thrombi still existed even 6 months after implantation. Intravascular findings of PTFE-covered stent may vary between the observational periods. Furthermore, vascular healing process of this special stent may be different from those of non-covered mesh stents.

<Learning objective: Even with the use of IVUS and OCT, it may be difficult to evaluate apposition of PTFE-covered stent just after implantation. However, it could be visualized as being sufficiently similar to the other common stents at 6-month follow-up. Unique longitudinal NIH distribution (bilateral edge dominant) was evaluated, and existence of micro thrombi within PTFE-covered stent even at 6 months.>

Keywords: Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent, OCT, IVUS, Angioscopy

Introduction

Perforation of coronary arteries is a complication that is often encountered during percutaneous coronary intervention. With the advance of new devices and technologies, interventionalists attempt to treat more complex lesions, including more calcified or tortuous arteries, which increases the complication of perforation. The use of a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-coated stent in coronary perforation cases may stop the bleeding at perforation sites. This case report contains serial documentation using rare multi-intravascular imaging devices for PTFE-coated stents.

Case report

This case report involves a 47-year-old Japanese male who had previously undergone coronary bypass surgery. The patient did not have hereditary factors, or the risk factors of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and long-term smoking, causes of acute coronary syndrome. In the year after coronary bypass surgery, a bare metal stent (size unknown) was deployed from left main (LM) trunk to left circumflex artery because of angina. The patient was transferred to our hospital for treatment of left main in-stent restenosis after bare metal stent implantation, because sufficient lesion dilatation had not been achieved, due to severe coronary calcification of his LM lesion. His bypass graft was previously patent from left internal mammary artery to left anterior descending artery.

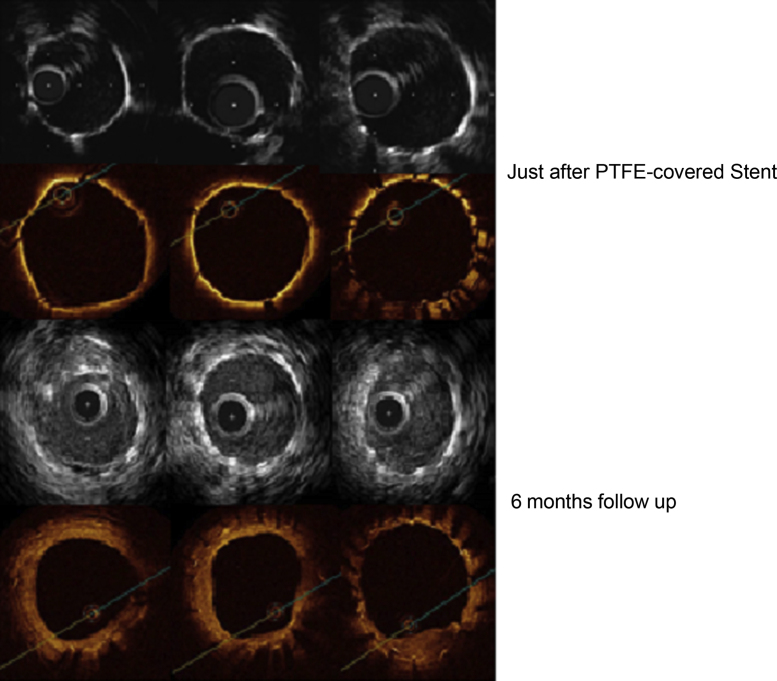

A repeat coronary intervention was performed for this calcified LM lesion. Immediately after balloon (non-compliant 3.25/15 mm, max 18 atm dilatation) dilatation following rotational atherectomy (burr 1.25 and 1.5 mm, max 200,000 rotation), coronary perforation occurred because of severe calcification and was treated with the tortuous lesion from LM to circumflex branch. Finally, hemostasis was achieved using a PTFE-covered stent (Jostent GraftMaster 3.0/18 mm, Abbott, Abbott Park, IL, USA) after prolonged compression by balloon (Fig. 1). Additional stent dilatation was performed using a non-compliant balloon at a high pressure of 30 atm. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) were documented to evaluate apposition of the PTFE-covered stent (Fig. 2). IVUS system was used, namely, Atlantis Pro-2 and Galaxy-2 system (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA). Conventional IVUS images were acquired using a 40-MHz mechanically rotating IVUS catheter. OCT imaging was performed during occlusion of the proximal coronary artery with a compliant balloon (4Fr occlusion balloon catheter, Helios, Light Lab Imaging, Westford, MA, USA) and continuous flushing. The fluid flush comprised 1 part dextran 40 to 3 parts lactated Ringer's solution. However, vascular structures outside the stent were not adequately evaluated by either IVUS or OCT because PTFE tube might interfere with ultrasound beam or light penetration.

Fig. 1.

A repeat coronary intervention was performed for left main lesion with severe calcification. After rotational atherectomy (burr 1.5 mm) and plain old balloon angioplasty, coronary perforation occurred. Red arrows show perforation site of left main lesion. As a result, a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered stent was implanted from left main lesion to proximal of left circumflex artery. Yellow arrows show range of PTFE-covered stent. After 6-month follow-up angiography, there was no in-stent restenosis in PTFE-covered stent. PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Fig. 2.

Apposition of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered stent by optical coherence tomography (OCT) and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) just after stent implantation into perforated left main trunk and follow-up at 6 months after implantation of PTFE-covered stent. In the acute period, the outside of a stent cannot be observed. However, it was possible to have observed with IVUS and OCT the outside of PTFE after 6 months without high-intensity image of PTFE.

Follow-up coronary angiography, IVUS, OCT, and angioscopy were obtained at 6 months. There was no ISR at the PTFE-covered stent by coronary angiography (Fig. 1). Although vascular structures outside of a PTFE-covered stent could not be observed by IVUS or OCT just after implantation, they could be visualized and differentiated at 6-month follow-up (Fig. 2). PTFE membrane was clearly observed at baseline, however it became difficult to differentiate from surrounding tissue at 6-month follow-up. Representative frames of bilateral stent edges and mid-portion observed by OCT and angioscopy are shown in Fig. 3. Longitudinal neointimal hyperplasia (NIH) distribution detected by OCT demonstrated a unique pattern. NIH was dominantly distributed at both stent edges. In contrast, neointimal coverage around the stent mid-portion was thin. According to angioscopy, the middle of the PTFE-covered stent was almost NSC [1] (angioscopic images of Neointimal Stent Coverage) Grade 0 (no neointima found on stent struts) or partially Grade 1 (struts were visible under the thin neointima). Furthermore, several subclinical micro thrombi were observed in mid lesion of PTFE-covered stent by OCT (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Follow-up optical coherence tomography (OCT) and angioscopy of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered stent after 6 months. Yellow arrow shows range of PTFE-covered stent, yellow asterisk is angioscopy wire. Neointimal hyperplasia (NIH) at stent proximal and distal edge was observed in PTFE-covered stent by OCT from short-axis and longitudinal images. NIH at stent mid lesion was not observed by OCT and struts were visible by angioscopy (NSC grade 0 or 1).

Fig. 4.

Follow-up coronary optical coherence tomography (OCT) after 6 months. Micro thrombi (A to C) were observed in mid lesion of polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent by OCT. They were identified as low-backscattering projections in the lumen of the artery and without distal shadowing. Therefore these structures were identified as white thrombus.

Proprietary offline software (Light Lab Imaging) was used to delineate the lumen contours of each cross-sectional image. Lumen, stent, and neointimal thickness mean areas and volumes were calculated every 5 frames along the entire stented segment. Standard definitions of cross-sectional area and volume measurements were applied as previously reported 2, 3, 4.

We analyzed the OCT imaging inside a PTFE-covered stent using proprietary offline software. We calculated every 5 frames (total of 720 Struts at 56 frames). The details about lumen profile are shown in Table 1. According to our data, there were 96% (688/720) well apposed embedded covered struts. Although there was no malapposed strut, 3% (24/720) of uncovered struts existed.

Table 1.

Optical coherence tomography analysis data.

| Mean lumen area (mm2) | 3.09 ± 0.67 |

| Minimum lumen area (mm2) | 1.95 |

| Mean stent area (mm2) | 4.48 ± 0.79 |

| Minimum stent area (mm2) | 2.99 |

| Mean neointimal area (mm2) | 1.39 ± 0.91 |

| Lumen volume (mm3) | 57.1 |

| Stent volume (mm3) | 82.8 |

| Neointimal volume (mm3) | 25.7 |

| Total number of struts | 720 |

| 1, Embedded covered struts | 688 |

| 2, Protruding covered struts | 8 |

| 3, Uncovered apposed struts | 24 |

| 4, Uncovered and malapposed struts | 0 |

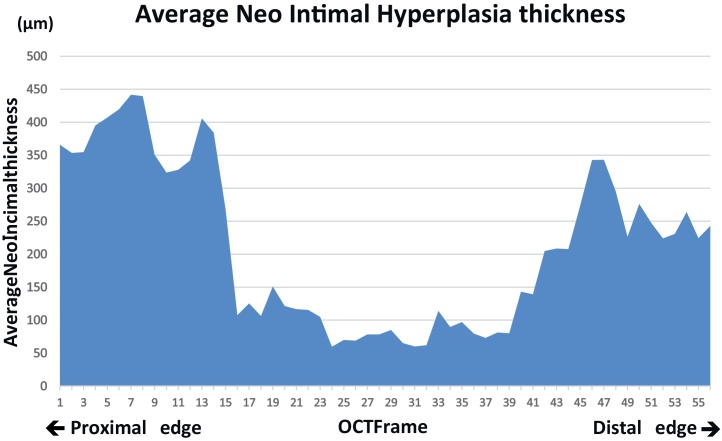

Fig. 5 shows the average NIH thickness at every frame from the proximal lesion to distal lesion of the PTFE-covered stent. NIH thickness of bilateral edges looked thick compared with that of middle portion.

Fig. 5.

Average neointimal hyperplasia (NIH) thickness at every frame from the proximal lesion to distal lesion of polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent. Analysis object was total of 720 struts at 56 frames (12.9 ± 1.55 struts/frame). White thrombi (Fig. 4) were observed for NIH around thin frame 35.

Discussion

This case report is unique because serial assessment by several representative intravascular imaging modalities is available to evaluate PTFE-covered stent. Interesting observations in this case can be summarized as the following: (1) just after implantation of PTFE-coated stent, PTFE was clearly visible as “light band” by IVUS or OCT, and vascular structure beyond PTFE could not be evaluated at all; (2) at 6-month follow-up, this “light band”, suggesting PTFE, could not be clearly differentiated anymore, and vascular structures including intima and peri-stent tissue could be evaluated sufficiently, similar to other common stents; (3) unique longitudinal NIH distribution was evaluated (bilateral edge dominant); and (4) there were micro thrombi within the PTFE-covered stent even at 6 months. General experiences of intravascular imaging modalities for PTFE-covered stent are limited 5, 6, 7, 8. To the best of our knowledge, this might be the first report, containing serial documentation using multi-intravascular imaging devices for PTFE-coated stents.

The material of PTFE itself disturbs neither an ultrasound nor an OCT signal. Just after deploying a stent, even if imaging modality is used, there are small gaps between a PTFE-covered stent and the surface of coronary arteries making it difficult for observation, and this may disturb ultrasound and OCT signals. Therefore, PTFE-covered stent and vascular intima might integrate in the chronic phase, small gaps might disappear, and it may become observable by IVUS and OCT.

In terms of the variability of visibility of PTFE-covered stent, vascular healing process for this material may play an important role. The several microns small hole is innumerably open to PTFE-covered stent, and is said that NIH stretches through the hole to it. If vascularized tissue covers all the PTFE-covered stent, it would be expected to become an organized lump containing PTFE and the intensity of Echo backscatter and optical reflection become comparatively uniform.

Unique NIH distribution may be the other issue to be discussed. From our data, although it did not result in restenosis, it was clear that NIH was distributed at proximal and distal edges (Fig. 5). Several previous studies have indicated that neointimal hyperplasia predominantly occurred at the most plaque accumulated sites. Usually, (1) minimal lumen diameter site, which should be mostly mid-portion of the stent, or (2) bilateral stent edges were representative for bare metal stent restenosis. On the other hand, NIH distribution patterns of drug-eluting stents (DES) were somewhat different from bare metal stents (BMS) 9, 10. Statistically significant more neointimal hyperplasia can be observed at bilateral stent edge portions. One report focusing on PTFE-covered stent is available. Gercken et al. [7] reported that follow-up IVUS interrogation demonstrated that neointimal proliferation occurred predominantly at the stent edges. Furthermore, there is a report that re-stenosis had occurred only at proximal and distal edges of PTFE-covered stents at 6-month follow-up [8] and lumen late losses at bilateral stent edges were larger than that of stent mid portion [9]. Thus, longitudinal distribution pattern of NIH following PTFE-covered stent implantation appeared to be similar to that of DESs. Considering this nature, we speculate that NIH covering process might be more predominant in bilateral stent edges than in stent body, due to existence of PTFE material. One group reported that they had used longer sirolimus-eluting stents beneath the PTFE-covered stent for 9 consecutive coronary perforation cases in order to prevent such edge restenosis, which appeared to be reasonable [11].

Although PTFE-coated stent was not equipped with antiproliferative agent, this case suggested several findings of delayed vascular responses, including existence of micro thrombi, and thin NIH-covered portions. Thus, delayed vascular healing process may be considered for this covered stent. In the RECOVERS trial [12], PTFE-covered stents implanted in saphenous vein grafts showed a higher incidence of 30-day subacute myocardial infarction than conventional stents (10.3% vs 3.4%, respectively). Furthermore, a previous study demonstrated a relatively high incidence of subacute stent thrombosis (5.7%) [7]. Existence of PTFE material on the surface of the relatively small caliber vessel may be more thrombogenic until completely endothelialized. Also in our case, the thrombus was observed for NIH around the thin frame (Frame 35, Fig. 5). Therefore, the possibility that platelet aggregation happened in response to uncovered metal was suggested [13]. Prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy compared with BMS might be considered as suitable for this stent.

Finally, from our experience of simultaneous usage of 3 intravascular imaging modalities, we should remember that it may be difficult to judge strut apposition or vascular conditions beyond PTFE membrane at the timing of the procedure no matter how we select intravascular imaging modalities. However, it should be meaningful because stent dimension can be sufficiently measured using either IVUS or OCT. In contrast, OCT may be the most advantageous for the observation of PTFE-coated stent at the timing of follow-up, thanks to its higher resolution which enables precise assessments of in-stent structures such as neointimal coverage, neointimal thickness, endothelialization, and micro thrombi, without substantial information losses. Further clinical experiences may warrant our current experiences.

Conclusion

Intravascular findings including vascular structures outside the covered stent could be observed sufficiently by both IVUS and OCT at this time that could not be seen at all just after implantation, neointimal hyperplasia distributed dominantly at both stent edges, and in-stent micro thrombi still existed even 6 months after implantation. Intravascular findings of PTFE-covered stent may vary between the observational periods. Furthermore, vascular healing process of this special stent may be different from those of non-covered mesh stents.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Takano M., Yamamoto M., Murakami D., Inami S., Okamatsu K., Seimiya K., Ohba T., Seino Y., Mizuno K. Lack of association between large angiographic late loss and low risk of in-stent thrombus: angioscopic comparison between paclitaxel- and sirolimus-eluting stents. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:20–27. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.769448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maehara A., Minz G.S., Lansky A.J., Witzenbickler B., Guagliumi G., Brodie B., Kellet M.A., Parise H., Mehran R., Stone G.W. Volumetric intravascular ultrasound analysis of paclitaxel-eluting and bare metal stents in acute myocardial infarction: the harmonizing outcomes with revascularization and stents in acute myocardial infarction intravascular ultrasound substudy. Circulation. 2009;120:1875–1882. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.873893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalo N., Barlis P., Serruys P.W., Garcia-Garcia H.M., Onuma Y., Ligthart J., Regar E. Incomplete stent apposition and delayed tissue coverage are more frequent in drug-eluting stents implanted during primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction than in drug-eluting stents implanted for stable/unstable angina: insights from optical coherence tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanigawa J., Barlis P., Di Mario C. Intravascular optical coherence tomography: optimisation of image acquisition and quantitative assessment of stent strut apposition. EuroIntervention. 2007;3:128–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutary J., Zakhem B., DE Lucas C.B., Paulo M., Gonzalo N., Alfonso F. Treatment of a giant coronary artery aneurysm: intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography findings. J Interv Cardiol. 2012;25:82–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2011.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takano M., Yamamoto M., Inami S., Xie Y., Murakami D., Okamatsu K., Ohba T., Seino Y., Mizuno K. Delayed endothelialization after polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent implantation for coronary aneurysm. Circ J. 2009;73:190–193. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-07-0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gercken U., Lansky A.J., Buellesfeld L., Desai K., Badereldin M., Mueller R., Selbach G., Leon M.B., Grube E. Results of the Jostent coronary stent graft implantation in various clinical settings: procedural and follow-up results. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;56:353–360. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukito G., Vandergoten P., Jaspers L., Dendale P., Benit E. Six months clinical, angiographic, and IVUS follow-up after PTFE graft stent implantation in native coronary arteries. Acta Cardiol. 2000;55:255–260. doi: 10.2143/AC.55.4.2005748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehran R., Dangas G., Abizaid A.S., Mintz G.S., Lansky A.J., Satler L.F., Pichard A.D., Kent K.M., Stone G.W., Leon M.B. Angiographic patterns of in-stent restenosis: classification and implications for long-term outcome. Circulation. 1999;100:1872–1878. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.18.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirohata A., Morino Y., Ako J., Sakurai R., Buchbinder M., Caputo R.P., Karas S.P., Mishkel G.J., Mooney M.R., O'Shaughnessy C.D., Raizner A.E., Wilensky R.L., Williams D.O., Wong S.C., Yock P.G. Comparison of the efficacy of direct coronary stenting with sirolimus-eluting stents versus stenting with predilation by intravascular ultrasound imaging (from the DIRECT Trial) Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1464–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hou J., Jia H., Huang X., Yu H., Ren X., Fang Y., Han Z., Yang S., Meng L., Zhang S., Yu B., Jang I-K. Optical coherence tomographic observations of polytetrafluoroethylene-covered sirolimus-eluting coronary arterial stent. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:1117–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weintraub W.S., Jones E.L., Morris D.C., King S.B., III, Guyton R.A., Craver J.M. Randomized evaluation of polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent in saphenous vein grafts (RECOVERS trial) Circulation. 2003;108:37–42. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000079106.71097.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finn A.V., Joner M., Nakazawa G., Kolodgie F., Newell J., John M.C., Gold H.K., Virmani R. Pathological correlates of late drug-eluting stent thrombosis: strut coverage as a marker of endothelialization. Circulation. 2007;115:2435–2441. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.693739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]