Abstract

We report a case of syncope in a young patient who presented with high-degree, variable atrioventricular heart block. Despite having no other classic manifestations of Lyme disease, she was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone for Lyme carditis on high clinical suspicion due to geographic location. The heart block resolved within 24 h of treatment. Although rare, we demonstrate the importance of considering Lyme carditis in patients who present with new-onset heart block and a history of living in an endemic area. Initiation of empiric antibiotic therapy can lead to rapid resolution of this condition.

<Learning objective: Although uncommon, Lyme carditis may present without any other classic signs or symptoms of Lyme disease. It should be considered in any patient who presents with new-onset atrioventricular heart block and a history of living in an endemic area. Prompt initiation of empiric antibiotic therapy can be both diagnostic and therapeutic.>

Keywords: Lyme disease, Carditis, Heart block, Reversible

Introduction

Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne illness in the USA and Europe. Transmitted by the Ixodes tick, the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi causes the sixth most common nationally reportable infectious disease in the USA [1]. Specifically, most cases are reported in northeastern and northern midwestern states, with a peak in diagnoses occurring in the summer months. The delay in infection to patients’ presentation corresponds to the lifecycle of the Ixodes tick. The more infective nymph form of the tick is most prevalent between May and June, while the disease may take weeks to months to manifest [2].

Clinically, Lyme disease is categorized in three overlapping stages: early localized, early disseminated, and late stage disease. The cardiac manifestations are usually seen in early disseminated disease, which is also associated with multiple erythema migrans lesions, as well as neurologic complications. Approximately 1% of patients between 2001 and 2010 were reported to manifest cardiac derangements of Lyme disease [1]. Surveillance data collected between the years 1992 and 2006 corroborate this statistic, making cardiac involvement one of the rarer complications of the disease [2]. The cardiac abnormalities of early disseminated Lyme disease predominately involve the conduction system and myocardium. Most commonly, Lyme carditis affects the atrioventricular (AV) node, causing a conduction block of varying, and rapidly fluctuating, severity [3].

While several studies have reported on the incidence, progression, and cardiac derangements associated with Lyme carditis, reports vary widely on the length of time needed for full recovery with the implementation of antibiotic therapy. We present a case of a woman who was treated empirically for Lyme carditis, despite a vague history and unclear symptoms. Her rapid recovery shows both the diagnostic and therapeutic utility of early initiation of antibiotic treatment.

Case report

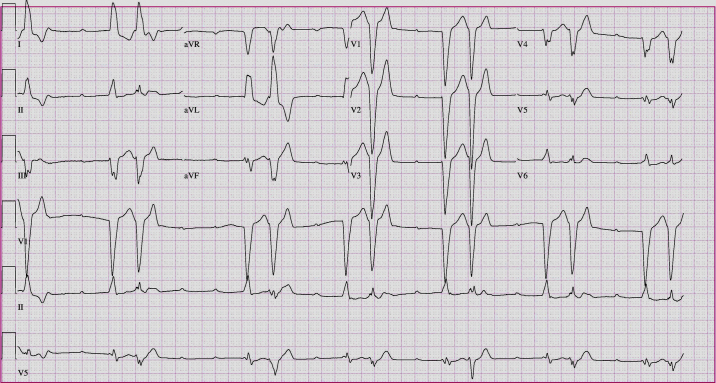

A previously healthy 28-year-old woman presented to our emergency department 1 h after a syncopal episode. She reported being in her usual state of health upon awakening that morning, but developed lightheadedness and chest discomfort while urinating. She subsequently lost consciousness. The syncopal episode was unwitnessed and of unknown duration. She regained consciousness spontaneously and emergency medical service was called. Upon their arrival, the patient was found to be bradycardic with a heart rate of 30–40 beats per minute (bpm). In the emergency department her heart rate slowed to around 20 bpm although she remained normotensive and all other vital signs were stable. The cardiac monitor initially showed wide complex tachycardia and she received magnesium sulfate intravenously. An electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed and showed high degree AV heart block (Fig. 1). Continuous cardiac monitoring subsequently revealed a varying type II second-degree AV heart block to third-degree AV heart block. She denied chest pain, shortness of breath, or palpitations but continued to feel light headed at the time of admission to the cardiac care unit.

Fig. 1.

Electrocardiogram showing sinus rhythm with first-degree atrioventricular heart block and intermittent high degree atrioventricular heart block. Heart rate 74 bpm. PR interval 416 ms.

Further history revealed that two weeks prior, she had a vaguely described erythematous skin rash on her left forearm but no further details were given. She denied any history of fever, chills, headache, fatigue, neck stiffness, myalgias, arthralgias, or weakness. She had no ongoing or past medical conditions, no allergies, and was not taking any medications on a regular basis. Her family history was unremarkable. She reported binge drinking the day before admission and use of cocaine the week previously. On admission, her vital signs showed a blood pressure of 110/64 mmHg, heart rate ranging between 20 bpm and 38 bpm, respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, and temperature of 37.6 °C. Oxygen saturation was 98% on 2 L via nasal canula. The rest of her physical examination revealed no evidence of skin rash or lymphadenopathy. Cardiac auscultation revealed irregular rhythm but otherwise no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Distal pulses were strong bilaterally. Neurologic examination showed no focal deficits.

Laboratory evaluation, including cardiac enzymes and urine toxicology screen for drugs of abuse, was unrevealing. Her leukocytes count was 14.5k/μL. The chest X-ray was unremarkable and the echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular size and systolic function.

The patient received 2 g intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone for presumed Lyme carditis, given high clinical suspicion due to new onset advanced heart block in the geographic setting of upstate New York, USA. Lyme IgG and IgM antibodies were drawn. The patient's heart rate began to improve, increasing to 50 bpm, by the evening of admission. The following morning, approximately 24 h after admission, the patient was continued on IV ceftriaxone and a repeat ECG showed sinus rhythm with first-degree AV block, with a rate of 70 bpm, and PR interval of 344 ms (Fig. 2). The patient remained hemodynamically stable and her symptoms of light-headedness resolved; 48 h later ECG showed a decreased PR interval to 300 ms with a heart rate of 56 bpm. Lyme antibodies with confirmatory Western blot for B. Burgdorferi AB IgG and IgM came back positive. The patient was deemed safe to be discharged home on oral doxycycline for 21 days after an uneventful hospital course.

Fig. 2.

Electrocardiogram showing sinus rhythm with first-degree atrioventricular heart block and a prolonged QTc (462 ms). Heart rate 70 bpm. PR interval 344 ms.

At follow-up 2 months after discharge, she had completed the course of antibiotics and denied any further episodes of dizziness, syncope or chest discomfort. ECG revealed a complete reversal of the AV heart block, with normal sinus rhythm, a rate of 61 bpm and a PR interval of 134 ms (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Electrocardiogram showing normal sinus rhythm. Heart rate 61 bpm and PR interval 134 ms.

Discussion

The diagnosis of Lyme disease can be challenging, and requires thorough history taking and a high index of suspicion in the appropriate clinical setting. In particular, new-onset heart block in an otherwise healthy patient must rouse consideration of Lyme carditis in order to prevent misdiagnosis and improper treatment. Antibiotics are often initiated before Lyme serologies return, but this empiric treatment is important in reducing or preventing further complications of the disease [4]. Oral antibiotics may be adequate for minor cardiac involvement, but hospitalization and intravenous ceftriaxone or high-dose penicillin G are generally necessary for severe carditis [5]. Up to 30% of patients may need temporary cardiac pacing, although few patients will require placement of a permanent pacemaker 6, 7.

This case demonstrates the rapid reversibility of the conduction derangements of Lyme carditis following antimicrobial therapy. However, a review of the literature reveals that the duration of cardiac involvement can be variable. While studies agree that this condition is usually self-limited, reports of complete resolution of the heart block have ranged between one to six weeks, with initial improvement in the degree of heart block seen within 24 to 48 h 3, 5, 8.

Severe complications, including myocarditis, pericarditis, tacchyarrhythmias, valvular disease and cardiac tamponade have been reported 9, 10. Few cases were fatal and some reports revealed permanent AV block as a result of Lyme carditis 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. The role of antibiotics in resolution of the conduction disturbances has not been adequately studied. However, it is well documented that the spirochetes invade the myocardium, as demonstrated by endomyocardial biopsies. Also antibiotics prevent other non-cardiac lyme sequelae and are therefore recommended in the management of Lyme carditis [16].

We report a patient with Lyme carditis, who presented with a vague history and without the classic symptoms of Lyme disease. A high index of suspicion for a conduction disturbance in the setting of living in an endemic area was critical and led to further testing and early initiation of empiric antibiotic treatment for Lyme carditis. This disease should be suspected in patients with a recent history of travel to endemic areas as well. We believe that this approach can be both diagnostic and therapeutic since there are currently no early serologic detection methods for the causative agent. It may improve outcomes and lead to a more favorable prognosis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Final 2010 reports of nationally notifiable infectious diseases. MMWR. 2011;60:1088–1101. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Surveillance for Lyme disease – United States, 1992–2006. MMWR. 2008;57:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steere A.C., Batsford W.P., Weinberg M., Alexander J., Berger H.J., Wolfson S., Malawista S.E. Lyme carditis: cardiac abnormalities of Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:8–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox J., Krajden M. Cardiovascular manifestations of Lyme disease. Am Heart J. 1991;122:1449–1455. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90589-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fish A.E., Pride Y.B., Pinto D.S. Lyme carditis. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2008;22:275–288. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinto D.S. Cardiac manifestations of Lyme disease. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:285–296. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(03)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagi K.S., Joshi R., Thakur R.K. Cardiac manifestations of Lyme disease: a review. Can J Cardiol. 1996;12:503–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAlister H.F., Klementowicz P.T., Andrews C., Fisher J.D., Feld M., Furman S. Lyme carditis: an important cause of reversible heart block. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:339–345. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-5-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruyn G.A., De Koning J., Reijsoo F.J., Houtman P.M., Hoogkamp-Korstanje J.A. Lyme pericarditis leading to tamponade. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:862–866. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.9.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canver C.C., Chanda J., DeBellis D.M., Kelley J.M. Possible relationship between degenerative cardiac valvular pathology and Lyme disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:283–285. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcus L.C., Steere A.C., Duray P.H., Anderson A.E., Mahoney E.B. Fatal pancarditis in a patient with coexistent Lyme disease and babesiosis. Demonstration of spirochetes in the myocardium. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:374–376. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-3-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavora F., Burke A., Li L., Franks T.J., Virmani R. Postmortem confirmation of Lyme carditis with polymerase chain reaction. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2008;17:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer W., Kleber F.X., Wilske B., Preac-Mursic V., Maciejewski W., Sigl H., Holzer E., Doering W. Persistent atrioventricular block in Lyme borreliosis. Klin Wochenschr. 1990;68:431–435. doi: 10.1007/BF01648587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van der Linde M.R., Crijns H.J., de Koning J., Hoogkamp-Korstanje J.A., de Graaf J.J., Piers D.A., van der Galiën A., Lie K.I. Range of atrioventricular conduction disturbances in Lyme borreliosis: a report of four cases and review of other published reports. Br Heart J. 1990;63:162–168. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.3.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Artigao R., Torres G., Guerrero A., Jiménez-Mena M., Bayas Paredes M. Irreversible complete heart block in Lyme disease. Am J Med. 1991;90:531–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costello J.M., Alexander M.E., Greco K.M., Perez-Atayde A.R., Laussen P.C. Lyme carditis in children: presentation, predictive factors, and clinical course. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e835–e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]