Abstract

Background

3.9% of men and 5.2% of women in Germany suffer from second-degree obesity (body mass index [BMI] = 35 to <40 kg/m2), and 6.5 million persons suffer from diabetes. Obesity surgery has become established as a further treatment option alongside lifestyle changes and pharmacotherapy

Methods

The guideline was created by a multidisciplinary panel of experts on the basis of publications retrieved by a systematic literature search. It was subjected to a formal consensus process and tested in public consultation.

Results

The therapeutic aims of surgery for obesity and/or metabolic disease are to improve the quality of life and to prolong life by countering the life-shortening effect of obesity and its comorbidities. These interventions are superior to conservative treatments and are indicated when optimal non-surgical multimodal treatment has been tried without benefit, in patients with BMI = 40 kg/m², or else in patients with BMI = 35 kg/m² who also have one or more of the accompanying illnesses that are associated with obesity. A primary indication without any prior trial of conservative treatment exists if the patient has a BMI = 50 kg/m², if conservative treatment is considered unlikely to help, or if especially severe comorbidities and sequelae of obesity are present that make any delay of surgical treatment inadvisable. Metabolic surgery for type 2 diabetes is indicated (with varying recommendation grades) for patients with BMI = 30 kg/m², and as a primary indication for patients with BMI = 40 kg/m². The currently established standard operations are gastric banding, sleeve gastrectomy, proximal Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, omega-loop gastric bypass, and biliopancreatic diversion.

Conclusion

No single standard technique can be recommended in all cases. In the presence of an appropriate indication, the various surgical treatment options for obesity and/or metabolic disease should be discussed with the patient.

The increased prevalence of obesity in Germany, particularly among young adults, presents a challenge to the healthcare system with major socioeconomic effects both now and in the future. According to the DEGS1 study (2013), 5.2% of women and 3.9% of men in Germany suffer from second-degree obesity (body mass index [BMI] = 35 to < 40 kg/m2); 2.8% of women and 1.2% of men suffer from third-degree obesity (BMI = 40 kg/m²) (1). It is stated in the German Health Report on Diabetes for the year 2017 that 6.5 million persons in the country now suffer from diabetes, 95% of whom have type 2 diabetes (2).

Surgery for obesity and metabolic disease is less common in Germany than in the neighboring Western European countries (Germany, 10.5 procedures per 100 000 persons per year; Benelux countries, 99.3 procedures per 100 000 per year), and there are also differences across the individual German federal states (Länder) (3).

The currently available nonsurgical treatments for weight reduction bring about sustained weight loss in only a small fraction of the persons treated and do not lower mortality (4). The controversial designation of surgical procedures as a “last resort” no longer appears in the new guideline. Moreover, the expression “bariatric surgery” has been replaced by “obesity surgery” in order to make it clear that such procedures are a treatment for the disease called “obesity.”

Readers are referred to the full guideline text for a discussion of special aspects such as surgery in adolescence or old age, pregnancy, perioperative management, and details of the surgical techniques, and to the guideline report for methodological aspects (5).

Methods

The guideline was created in accordance with the S3 guideline specifications of the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e. V., AWMF) under the aegis of the Surgical Working Group for the Treatment of Obesity (Chirurgische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Adipositastherapie, CAADIP) of the German Society of General and Visceral Surgery (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemein und Viszeralchirurgie, DGAV). The guideline was issued by the CAADIP. The German Obesity Society (Deutsche Adipositas-Gesellschaft), the German Diabetes Society (Deutsche Diabetes Gesellschaft), and seven other medical specialty societies and associations were represented on the guideline commission, which also included a patient representative (for a list of delegates, see eTable 1).

eTable 1. Composition of the guideline group: the participating specialty societies and associations and their delegates to the guideline-creating committee (collaborators*).

| Guideline-issuing society | Representatives/experts |

| Surgical Working Group for the Treatment of Obesity (CAADIP) of the German Society of General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV) | Prof. Dr. med. Arne Dietrich*, Leipzig (chairman) Prof. Dr. med. Lars Fischer*, Baden-Baden Dr. med. Daniel Gärtner*, Karlsruhe PD Dr. med. Mike Laukötter*, Münster Prof. Dr. med. Beat Müller-Stich*, Heidelberg Dr. med. Martin Susewind*, Berlin Dr. med. Harald Tigges*, Landsberg am Lech PD Dr. med. Markus Utech*, Gelsenkirchen Prof. Dr. med. Stefanie Wolff*, Magdeburg |

| Participating specialty societies and associations | Representatives/experts |

| German Obesity Society (DAG) | Prof. Dr. med. A. Wirth*, Bad Rothenfelde |

| German Diabetes Society (DDG) | PD Dr. med. Jens Aberle*, Hamburg |

| German Society of Nutritional Medicine (DGEM) | Prof. Dr. med. Arved Weimann*, Leipzig |

| German Society of Endoscopy and Imaging Techniques (DGE-BV) | Prof. Dr. med. Georg Kähler*, Mannheim |

| German Society of Psychosomatic Medicine and Medical Psychotherapy (DGPM) | Prof. Dr. Martina de Zwaan*, Hanover |

| German Society of Plastic, Reconstructive, and Esthetic Surgeons (DGPRÄC) | Prof. Dr. med. Adrian Dragu*, Dresden |

| German Collegium of Psychosomatic Medicine (DKPM) | Prof. Dr. Martina de Zwaan*, Hanover |

| Association of Diabetes Counseling and Educating Professions in Germany (VDBD) | Prof. Dr. rer. medic. Markus Masin*, Münster |

| Professional Association for Ecotrophology (VDOE) | Dr. rer. nat. Tatjana Schütz*, Leipzig (coordination) |

| German Obesity Surgery Self-Help Association | Andreas Herdt*, Kelsterbach |

A search for relevant publications (April 2009 to March 2016) was conducted in the Medline, Cochrane Library, and Scopus databases. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were sought.

The literature search yielded 9099 hits (after the elimination of duplicates); after multilevel screening, 261 were chosen for further evaluation. Priority was given to systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Evidence tables to be used as a foundation for the creation of the guideline were prepared for 56 systematic reviews and meta-analyses, one RCT, and five cohort studies; these tables were then evaluated by the SIGN procedure (6). Details are given in the guideline report (5) and in the eMethods.

Major elements of the guideline and changes since the preceding version

Treatment objectives

In older guidelines, weight loss was often said to be the therapeutic objective of obesity surgery. Nonetheless, empirical data on weight loss in kilograms, BMI points, or percentage excess weight loss (%EWL) do not adequately reflect whether the treatment has really achieved its objective.

The newly formulated objective of obesity surgery and metabolic procedures is to bring about a sustained loss of weight and, through the beneficial effects of weight loss, to achieve the following:

Better quality of life

Remission, improvement, and/or prevention of the comorbidities and sequelae of obesity

Longer survival

Continued participation in work and in social and cultural activities.

The goals of treatment should always be individually defined and adapted to any changes that take place. This formulation met with a strong consensus among the experts.

Definition of centers

Centers were defined in accordance with the certification rules of the DGAV (7) and the Swiss guideline on the surgical treatment of obesity (8).

The Barmer Health Report (9) and current German registry data (10) reveal that perioperative morbidity and mortality are lower in certified centers (e.g., 30-day mortality after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 0.2% in certified centers, 0.5% in uncertified centers, p = 0.002). There are also differences between the various types of certified center. For example, morbidity was lower in reference and excellence centers than in competence centers (10). To take due account of these data (even though their evidential quality is not high), the guideline commission decided to introduce the new category of “centers with special expertise.” Such centers are supposed to be certified by a specialty society, and the experience of the responsible surgeon should comprise at least 300 obesity operations.

There was a strong consensus among the experts that the following types of patients should undergo surgery only in a center with special expertise, and that the specified techniques should only be performed in such centers (however, this is not evidence based):

Patients under age 18, or aged 65 and above

Patients at elevated risk with severe comorbidities (American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] score >3)

Patients with BMI = 60 kg/m²

Distal bypass operations, conversion operations, and redo operations

Procedures that are primarily for the treatment of metabolic disease (in patients with BMI <40 kg/m², in collaboration with a physician who is an expert in the treatment of diabetes/a diabetologist).

Surgical indications

The treating team that establishes the indication for surgery should consist of the following members:

A surgeon with competence in the surgical treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders

An internist/general practitioner/physician with special expertise in nutrition who has competence in the surgical treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders

A mental health professional with experience in obesity surgery

A nutritionist or physician with special expertise in nutrition who has experience in obesity surgery

A physician who is an expert in the treatment of diabetes/a diabetologist, if surgery for metabolic indications (type 2 diabetes) is to be performed.

The term “obesity surgery” refers to any operation (e.g., sleeve gastrectomy) that is intended to bring about sustained weight loss and thereby prevent or improve obesity-associated comorbidities and improve the patient’s quality of life. The recommendations of the current guideline of the German Obesity Society (Deutsche Adipositas-Gesellschaft) (11) and of the American guideline (12) have been adopted.

Obesity surgery is indicated in the following situations:

In patients with BMI = 40 kg/m2 without any comorbidities or contraindications, when conservative treatment options have been exhausted and after the patient has been thoroughly informed.

In patients with BMI = 35 kg/m2, after the exhaustion of conservative treatment options, in the presence of one or more obesity-associated comorbidities, such as: type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, arterial hypertension, nephropathy, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), obesity-hypoventilation syndrome, Pickwick syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), pseudotumor cerebri, gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), asthma, chronic venous insufficiency, urinary incontinence, immobilizing joint disease, impaired fertility, or polycystic ovarian syndrome.

-

A primary indication for obesity surgery (i.e., without any requirement for prior exhaustion of conservative treatment modalities) exists if one of the following conditions is present:

BMI ≥ 50 kg/m2,

Whenever, in a specific case, the multidisciplinary team considers a trial of conservative treatment to have little or no chance of success, and

Whenever especially severe comorbidities and sequelae of obesity are present that make any further delay before surgery inadvisable.

Points 1 and (in part) 2 in the above list of obesity surgery indications are supported by evidence of the highest level (point 2 with respect to the therapeutic objective of weight control and improvement in biochemical markers of cardiovascular risk) and correspondingly, recommendations of the highest grade are given. A strong consensus supported all of the other points.

The exhaustion of conservative treatment is defined as follows, for the purpose of determining the indication for obesity surgery: if the patient has been unable to achieve a loss of >15% of the initial weight (BMI 35.0–39.9 kg/m²), or >20% of the initial weight (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m²), despite having undergone a comprehensive lifestyle intervention for at least 6 months within the past two years, then conservative treatment is considered to have been exhausted.

An indication is also present if this degree of weight loss has indeed been reached, but obesity-associated illnesses persist that could be improved by obesity surgery, or by surgery for a metabolic indication (i.e., type 2 diabetes). Likewise, if initially successful weight reduction has been followed by weight gain of more than 10%, then conservative treatment is considered to have been exhausted.

If a primary indication is present, then the patient’s adherence to treatment regimens should be considered before any procedure is carried out. The patient should change his/her nutrition and eating habits in a manner appropriate to the coming operation for the treatment of obesity.

The expression “surgery for a metabolic indication” or “metabolic surgery” refers to the same surgical procedures that are performed to treat obesity when they are performed primarily in order to improve glycemic metabolism in patients with pre-existing type 2 diabetes.

In its recommendations on the indications for the surgical treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (“metabolic surgery”), the guideline commission adopted the recommendations of the American Diabetes Association’s Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2017 (13) and of the “Joint Statement by International Diabetes Organizations” (14).

The existing evidence is inadequate to support an indication for the surgical treatment of other “metabolic” disturbances associated with obesity (e.g., dyslipidemias, hypertension).

Surgery is indicated to treat a metabolic disturbance in the following situations:

Metabolic surgery should be recommended as a primarily indicated treatment option, as defined above, to patients with type 2 diabetes who also have a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m², as such patients stand to benefit both from the antidiabetic effect and from the weight-reducing effect of the intervention.

Metabolic surgery should be recommended as a potential treatment option to patients with type 2 diabetes whose BMI lies in the range of ≥ 35 kg/m² to <40 kg/m² if their individual target values, as determined from the National Disease Management Guideline on the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes, have not been achieved.

Metabolic surgery can be considered for patients with type 2 diabetes whose BMI lies in the range of ≥ 30 kg/m² to <35 kg/m² if their individual target values, as determined from the National Disease Management Guideline on the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes, have not been achieved.

The first two points above are supported by evidence of the highest level, and there was a strong consensus for all recommendations.

The background for these recommendations is the fact that patients with type 2 diabetes stand to benefit doubly from the intervention, i.e., both by losing weight and by experiencing an improvement or even a remission of their diabetes. Many studies of high quality (RCTs and meta-analyses) have shown the superiority of surgery over conservative treatment in these situations, justifying the recommendations above (15).

Zhang et al., in a meta-analysis of 21 studies, found a significant advantage of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) over sleeve gastrectomy (SG) with respect to the rate of remission of type 2 diabetes (odds ratio [OR] = 3.29, 95% confidence interval [CI]: [1.98; 5.49], p <0.001) (16).

Schauer et al. performed a randomized controlled trial comparing conservative treatment versus SG or RYGB in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Five years after treatment, 45% of patients in the RYGB group were in complete remission (normal HbA1c without antidiabetic medication); the figure in the SG group was only 25% (p <0.05) (17).

Contraindications

There was also a strong consensus among the experts regarding contraindications. Obesity surgery and/or surgery for metabolic indications should not be performed in the following situations:

If the patient is in an unstable psychopathological state, e.g., untreated bulimia nervosa or ongoing substance dependence

In the presence of underlying diseases associated with a catabolic state, malignant neoplasms, untreated endocrine disturbances, or other chronic diseases that could be made worse under the catabolic conditions brought about by the operation

If the patient is pregnant or intends to become pregnant in the near future.

These contraindications are relative, except for pregnancy, and they are not supported by evidence. The decision should be made on the basis of an individualized, interdisciplinary risk–benefit analysis. Decisions against surgery should be re-evaluated if the disease that was considered a contraindication has been successfully treated, or if the contraindicating psychopathological state has been stabilized.

Surgical procedures and results

No procedure can be recommended as a universal standard; the choice of treatment is an individual one, taking due consideration of the initial weight, accompanying diseases if any, the patient’s wishes, etc. Currently established standard techniques include gastric banding (laparoscpic adjustable gastric banding, LAGB), sleeve gastrectomy (SG), proximal Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), omega-loop gastric bypass (MGB), and biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch (table 1). The evidence profile of the various techniques is presented in Table 2.

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of various types of primary obesity surgery and of primary surgery for metabolic indications.

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) | Good risk–benefit profile, can be performed even in patients with very high BMI (two-step approach) | Inferior to RYGB with respect to long-term weight control, reflux control, and diabetes remission |

| Proximal Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) | Good control of reflux disease, superior to SG in its metabolic effect | Same mortality as SG with higher morbidity Risk of dumping syndrome, ulcers, and internal hernias Risk of malabsorption |

| Omega-loop gastric bypass (MGB) | Lower perioperative morbidity than RYGB, because there is only a single anastomosis | Elevated risk of malabsorption with long biliopancreatic loop Risk of dumping syndrome and internal hernias Unclear effects of potential reflux of bile into the gastric pouch |

Table 2. Evidence profile of surgical procedures (long-term results) (5).

| Procedure | Percentage loss of excess weight [95% CI]*1 | |||||

| ≤ 2 years | Reference | >2 to <5 years | Reference | ≥ 5 years | Reference | |

| Gastric banding |

28.7–48 52.3 [48.7; 55.9] 43.9 [ 40.3; 47.5] |

(23) (18) (21) |

43.5 [38.5; 48.5] 49.0 [ 44.0; 54.0] |

(19) (21) |

34.7 [23.5; 49.9] 57.2 [47.2; 67.2] |

(19) (18) |

| Sleeve gastrectomy |

49–81 46.7 [42.9; 50.6] |

(23) (18) |

36.3 [33.1; 39.5] | (19) | 49.5 [39.3; 59.7] | (19) |

| Gastric bypass*2 |

62.1–94.4 80.1 [65.7; 94.4] 58.0 [54.3; 61.8] |

(23) (18) (21) |

49.4 [10.8; 88.0] 63.3 [58.4; 68.1] |

(19) (21) |

61.3 [55.2; 67.4] 64.9 [44.3; 85.6] |

(19) (18) |

| Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch | 56.0 [47.9; 64.2] | (21) | 73.7 [69.0; 78.4] | (21) | 49.3 [38.7; 59.9] | (19) |

| Procedure | Diabetes remission rate*3 in % [95% CI] | |||||

| ≤ 2 years | Reference | >2 to <5 years | Reference | ≥ 5 years | Reference | |

| Gastric banding |

62 [46; 79] 68 [50; 83] 82.3 [7 1.4; 93.1] |

(24) (18) (21) |

62.5 [42.2; 79.2] 78.7 [53.8; 100.0] |

(19) (21) |

24.8 [10.9; 47.2] | (19) |

| Sleeve gastrectomy |

53.3 60 [51; 70] 86 [73; 94] |

(23) (24) (18) |

64.7 [42.2; 82.1] | (19) | 58.2 [30.8; 81.3] | (19) |

| Gastric bypass*2 |

83 77 [ 72; 82] 93 [85; 97] 84.0 [72.9; 95.0] |

(23) (24) (18) (21) |

71.6 [59.9; 81.0] 85.3 [ 70.9; 99.7] |

(19) (21) |

75.0 [63.1; 84.0] | (19) |

| Biliopancreatic diversion | 89 [83; 94] | (24) | – | – | ||

| Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch | 100.0 [93.2; 100.0] | (21) | 98.9 [96.6; 100.0] | (21) | 99.2 [97.0; 99.8] | (19) |

*1 No data are available for percentage loss of excess weight after biliopancreatic diversion.

*2 proximaler Roux-en-Y-gastric bypass (RYGB), mini-bypass, and bypass procedures that were not further specified.

*3 High heterogeneity in definitions of diabetes remission between primary studies and systematic reviews.

Fields are left empty if no high-quality evidence on the level of a systematic review or a meta-analysis is available.

All evidence summarized here is from systematic reviews and meta-analyses with SIGN evidence level 2+/++. The evidence tables corresponding to the systematic reviews and meta-analyses cited here are presented in the guideline report. CI, confidence interval

The findings of two high-quality meta-analyses regarding the more common procedures are worth examining in detail. Chang et al. carried out a meta-analysis (evidence level 2 ++) using data from 37 RCTs and 127 observational studies, which were derived from a total of 161 756 patients (18). They studied the relative effects of various interventions on ? BMI (RYGB as reference; 5 years of follow-up), as revealed by 17 RCTs, in a mixed-treatment meta-analysis. Nonsurgical interventions led to the smallest reduction of BMI; 14 (6– 22) additional BMI points of weight loss were achievable with RYGB. SG led to similar results. In the RCTs, the rate of remission of pre-existing type 2 diabetes 5 years after surgery was 92% (95% CI: [85; 97]).

Yu et al. (evidence level 2 ++, meta-analysis of 2 RCTs and 24 cohort studies, 2.1–20 years of follow-up) studied the long-term effects of obesity surgery on type 2 diabetes (19). For all procedures combined, the mean weight loss on last follow-up was 50.5% EWL (95% CI: [43.8; 57.2]). The mean BMI reduction after various procedures was: BPD/DS (biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch), 18.8 kg/m2 (95% CI: [18.9; 18.7]); RYGB, 12.6 kg/m2 (95% CI: [20,1; 5,1]); AGB (adjustable gastric banding), 11.3 kg/m2 (95% CI: [13.4; 9.2]); sleeve gastrectomy, 10.4 kg/m² (95% CI: [15.0; 5.7]).

The rate of complete remission of pre-existing type 2 diabetes for all procedures combined was 64.7%, and the rate of improvement or remission was 89.2%. The remission rate was highest after BPD/DS (99.2%; 95% CI: [97.0; 99.8]), followed by RYGB (74.4%; 95% CI: [66.9; 80.6]), SG (61.3%; 95% CI: [45.9; 74.8]), and AGB (33.0%; 95% CI: [16.1; 55.8]). Subgroup analyses revealed no statistically significant differences across procedures with respect to either weight loss or diabetes remission.

Long-term data are available, for example, from the SOS study (a prospective interventional study) (20). The mean weight loss among patients who underwent surgery was 18% at 20 years after the procedure. These patients, in comparison to the conservatively managed control group, had lower overall mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.71, 95% CI: [0.54; 0.92]; p = 0.01) and lower rates of myocardial infarction and stroke (adjusted HR 0.71, p = 0.02, and 0.66, p = 0.008, respectively).

All of the standard procedures of obesity surgery were rated as positive over the long term in a risk–benefit analysis (18, 20, 21).

The perioperative morbidity and mortality of obesity surgery are relatively low. In the large-scale meta-analysis of Chang et al. (18), the 30-day mortality of surgery in the RCTs was 0.08 % (95% CI: [0.01; 0.24]), which is lower than that of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The perioperative morbidity in the RCTs was 17% (95% CI: [11; 23]), consisting mainly of minor complications (18). The most common complications of obesity surgery (all of them rare) were staple-line fistula, anastomosis insufficiency, abscess, and bleeding.

Postoperative care

Meticulous postoperative care is indispensable and is supported by a strong expert consensus. The evidence regarding the proper extent of postoperative care is not of high quality, but the outcome is clearly better in patients who receive intensive postoperative care and participate in self-help groups (22). The key elements of postoperative care are the following:

Checking whether the goal of treatment has been reached

Monitoring comorbidities and changing medications as indicated

Encouraging the patient to exercise and follow a proper diet

Early recognition of complications, etc.

There was expert consensus concerning the timing of follow-up examinations and laboratory checks: after surgery for obesity and/or metabolic indications (except gastric banding), follow-up examinations should take place at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months, and then annually. Laboratory values should be checked at 6 and 12 months, and thereafter at intervals depending on the particular surgical procedure and on the patient’s comorbidities. At least the following should be checked:

Complete blood count, electrolytes, hepatic and renal function tests, blood glucose and HbA1c (only in diabetics), vitamins B1and B12, albumin, calcium, folic acid, ferritin

After any type of bypass procedure: 25(OH)D3, parathormone, vitamin A

After distal bypasses: zinc, copper, selenium, magnesium.

Patients with preoperatively recognized mental illness and/or self-injurious behavior should be actively questioned postoperatively about the presence, recurrence, or worsening of their mental problems, and about suicidality.

Successful weight loss may necessitate skin-removal surgery, particularly from the abdomen and the thighs, but sometimes even from the arms and chest. Consultation with a plastic surgeon should be made available to the patient.

Prophylactic dietary supplementation is indicated after any type of surgery for obesity or a metabolic indication. Dosage recommendations for the individual micronutrients are given in Table 3.

Table 3. Prophylactic supplementation after surgery for obesity or surgery for metabolic indications (5).

| SG | RYGB | BPD-DS | |

| Protein (total per day [d]) | >60 g/d | >60 g/d | >90 g/d |

| Folic acid | MVM preparation bid | 600 μg/d | |

| Vitamin B1 | MVM preparation bid, no dose recommendation | ||

| Vitamin B12 | p.o.: 1000 μg/d IM: 1000 – 3000 μg/d every 3 to 6 months |

||

| Vitamin A | MVM preparation bid |

MVM preparation bid |

1–2 × 25 000 IU/d |

| Vitamin D | At least 3000 IU/d, serum concentration >30 ng/mL | ||

| Vitamins E, K | MVM preparation bid, no dose recommendation | ||

| Calcium citrate | 1200 – 1500 mg/d | ||

| Iron sulfate, fumarate, gluconate | MVM preparation bid |

50 mg/d | 2 x 100 mg/d |

| Magnesium citrate | 200 mg/d | ||

| Zinc gluconate, sulfate, acetate |

MVM preparation bid |

MVM preparation bid |

8–15 mg/d |

| Copper gluconate, oxide, sulfate Selenium as sodium selenite |

No recommendation | MVM preparation bid with 2 mg/d of copper |

|

MVM preparation, multivitamin and mineral preparation. A preparation should be chosen that is rich in ?micro?nutrients, in amounts that are within 100% of the RDA (recommended daily allowance).

SG, sleeve gastrectomy; RYGB, proximal Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; BPD-DS, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch.

These recommendations are for the prevention of deficiency states; dose adaptation is necessary for patients with documented deficiency or corresponding symptoms. Regardless of the procedure performed, adequate amounts of MVM cannot be given immediately postoperatively because of the temporary restriction of food intake. Patients who have undergone surgery with techniques that cause more pronounced malabsorption (all distal bypasses with a short common channel or long alimentary and/or biliopancreatic loops) should receive the same type of supplementation as patients who have had a BPD-DS procedure.

There are no data or recommendations on the appropriate duration of prophylactic supplementation after LAGB (laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding) or SG. Patients who have undergone any type of bypass should receive supplementation for life. Depending on the type of surgical procedure and the patient’s nutritional state, adequate intake of macro- and micronutrients may be at least partly achievable.

After LAGB, an MVM preparation qd + 1200–1500 mg calcium + 3000 IU vitamin D are recommended.

Supplementary Material

eMETHODS: ON THE CREATION OF THE GUIDELINE

The guideline committee

As required by the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF), other specialty societies (i.e., societies other than the one mainly responsible for the guideline), corresponding to the intended users of the guideline, were included in the committee; a patient representative was included as well (etable 1). The conflict of interest statements submitted by all committee members, as required by the AWMF, are incorporated in the guideline report (5).

The literature search

The guideline was created in collaboration with the UserGroup—Medizinische Leitlinienentwicklung e. V., CGS Clinical Guideline Services, Berlin, and with the counseling and interactive support of the AWMF. The literature search and evaluation were carried out by the UserGroup—Medizinische Leitlinienentwicklung e. V. in collaboration with the guideline committee. On the basis of questions formulated according to the PICO scheme, and corresponding algorithms, a search for literature published from April 2009 to March 2016 was carried out in the Medline, Cochrane Library, and Scopus databases. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were sought.

Results of the literature search

The literature search yielded 9099 hits (after the elimination of duplicates), which were subjected to multilevel screening. 7920 were excluded by screening of titles and abstracts, leaving 1179 for full-text screening. 833 were excluded, leaving 353 publications that were intended to be used in the evaluation of the literature on all key questions. After correction for publications that were counted more than once because they were relevant to multiple key questions, and therefore appeared in multiple literature groups, the number remaining for evaluation was 261.

Evaluation of the evidence

The evidence was evaluated by the SIGN method (etable 2) (6). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were given priority. RCTs and cohort studies that were included in systematic reviews of good or very good quality were not individually evaluated. If two or more reviews overlapped in more than half of the studies that they included, only the review that was of the highest quality and had the most recent publication date was considered. In this way, the 261 publications chosen for analysis after full-text screening were reduced to a set of 56 systematic reviews and meta-analyses and, as requested by the experts, one RCT and five cohort studies.

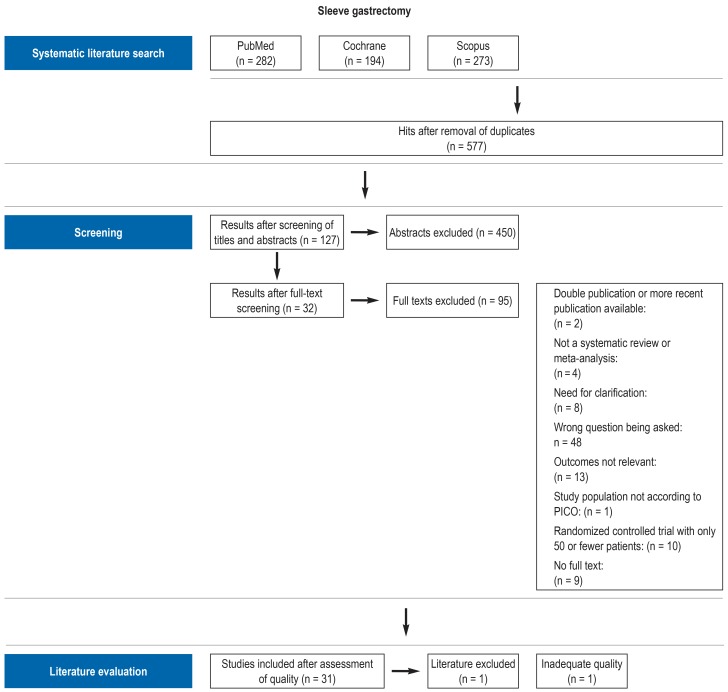

PRISMA charts on the screening algorithm for the literature search on each topic, including reasons for the exclusion of publications, can be seen in the guideline report (eFigure) (5). In the next step, data were extracted from the included publications and summarized in the form of evidence tables.

Structured consensus-finding and formulation of the recommendations

After formulation of the guideline text and recommendations, the latter were evaluated and commented upon online in the framework of a formal consensus-finding process with two rounds of voting, then discussed a final time in the subsequent structured consensus conferences, where they were assigned recommendation grades (etable 3) and consensus strengths (etable 4).

The recommendation grades were assigned on the basis of the evidence, as well as further criteria such as the consistency of study findings, the clinical relevance of the endpoints and effect strengths, risk–benefit ratios, the applicability of the study findings to the target group of patients and to the healthcare system, the implementability of the recommendations in routine care, patient preferences, and ethical and legal aspects.

Recommendations that were not study-based were designated as “expert consensus.” These recommendations represent good clinical practice still in need of confirmation by scientific studies, or for which such confirmation cannot be expected because any relevant studies would be considered unethical.

The resulting guideline text was submitted to all participating specialty societies (and by some of these to their respective membership), discussed in multiple rounds, and amended as indicated. Compromises that were acceptable to the guideline committee could be found on all points, so that no special votes were necessary.

Key Messages.

Various surgical methods can be used, depending on the specific indication and the wishes of the patient: gastric banding, sleeve gastrectomy, proximal Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, omega-loop gastric bypass, and biliopancreatic diversion.

The most commonly performed procedures are sleeve gastrectomy and proximal Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. These can be expected to lead to a loss of 50–65% of excess weight over the intermediate term, and to the remission of pre-existing type 2 diabetes in 60–75% of the patients who have it.

In a meta-analysis, the 30-day mortality of such procedures was 0.08%, and the morbidity was 17%. The most common (but still rare) postoperative complications of obesity surgery are staple-line fistula, anastomosis insufficiency, abscess, and bleeding.

Structured postoperative care with frequent appointments is indispensable.

Depending on the type of procedure, the patient may need prophylactic supplementation of protein, vitamins, and trace elements.

eTable 2. Adapted evidence classification according to SIGN (6).

| Type of study | Categories | Risk of systematic errors | Descriptive quality |

| Systematic review with randomized controlled trials | 1+ | Low | Well-conducted |

| 1− | High | - | |

| 1++ | Very low | High-quality | |

| Systematic review with cohort or case–control studies | 2++ | Very low | High-quality |

| 2+ | Low | Well-conducted | |

| 2− | High | - | |

| Randomized controlled trial | 1++ | Very low | High-quality |

| 1+ | Low | Well-conducted | |

| 1− | High | - | |

| Cohort or case–control study | 2+ | Low | Well-conducted |

| 2− | High | - |

-, no verbal description given

eTable 3. Recommendation grades, according to the AWMF (25).

| Grade | Description | German verb |

| A | Strong recommendation |

Soll/soll nicht |

| B | Recommendation | Sollte/sollte nicht |

| 0 | Open recommendation |

Kann erwogen werden/kann verzichtet werden |

eTable 4. Adapted AWMF classification of consensus strength (25).

|

Strong consensus |

Consensus | Majority agreement | No consensus |

| Agreement 90% |

Agreement 75 – 90% |

Agreement 50 – 75% |

Agreement <50% |

eFigure 1.

Illustrative PRISMA chart for the literature search on sleeve gastrectomy

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Dietrich has served as a paid consultant for BOWA and has received reimbursement of meeting participation fees and of travel and accommodation costs from Medtronic, Johnson & Johnson, Bowa, and Novo Nordisc. He has received lecture honoraria from Bauerfeind, Johnson & Johnson, and BOWA.

Dr. Schütz has received reimbursement of meeting participation fees and of travel and accommodation costs from ETHICON and Johnson & Johnson.

Dr. Aberle, Prof. Wirth, Prof. Müller-Stich, and Dr. Tigges state that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Mensink GB, Schienkiewitz A, Haftenberger M, Lampert T, Ziese T, Scheidt-Nave C. Overweight and obesity in Germany: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1) Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2013;56:786–794. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deutsche Diabetes Gesellschaft und diabetesDE - Deutsche Diabetes-Hilfe. Deutscher Gesundheitsbericht Diabetes 2017. Die Bestandsaufnahme. www.diabetesde.org/system/files/documents/gesundheitsbericht_2017.pdf (last accessed on 12 March 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hüttl TP, Stauch P, Wood H, Fruhmann J. Aktueller Stand der Adipositas- und metabolischen Chirurgie: Bariatrische Chirurgie. Akt Ernahrungsmed. 2015;40:256–274. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, et al. Look AHEAD Research Group. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:145–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie. S3-Leitlinie Chirurgie der Adipositas und metabolischer Erkrankungen. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/II/088-001.html (last accessed on 12 March 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 50. A guideline developer’s handbook. www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign50_2015.pdf (last accessed on 12 March 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie. Ordnung. Das Zertifizierungssystem der DGAV (ZertO 5.1) www.dgav.de/fileadmin/media/texte_pdf/zertifizierung/Zertifizierungsordnung_DGAV_5_1.pdf (last accessed on 12 March 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swiss Society for the Study of Morbid Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (SMOB) Richtlinien zur operativen Behandlung von Adipositas (Administrative Richtlinien) www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/kuv-leistungen/referenzdokumente-klv-anhang-1/01-1-richtlinien-smob-operativen-behandlung-uebergewicht-administrative-richtlinien-gueltig-1-1-2018.pdf.download.pdf/01.1%20Richtlinien%20der% 20SMOB%20zur%20operativen%20Behandlung%20von%20%C3 %9Cbergewicht%20(Administrative%20Richtlinien)%20G%C3% BCltig%20ab%2001.01.2018.pdf (last accessed on 12 March 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Augurzky B, Wübker A, Pilny A, et al. Barmer GEK Report Krankenhaus. www.barmer.de/blob/36680/7729cf79a2d2610092725 d789517 a828/data/pdf-report-krankenhaus-2016.pdf (last accessed on 12 April 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroh C, Köckerling F, Lange V, et al. Obesity Surgery Working Group, Competence Network Obesity: does certification as bariatric surgery center and volume influence the outcome in RYGB-data analysis of German Bariatric Surgery Registry. Obes Surg. 2017;27:445–453. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deutsche Adipositas-Gesellschaft. Interdisziplinäre Leitlinie der Qualität S3 zur „Prävention und Therapie der Adipositas. Version 2.0 (2014) www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/050-001l_S3_Adipositas_Prävention_Therapie_2014-11.pdf (last accessed on 12 April 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient—2013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:159–191. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):1–135. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: ajoint statement by International Diabetes Organizations. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1144–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müller-Stich BP, Senft JD, Warschkow R, et al. Surgical versus medical treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in nonseverely obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2015;261:421–429. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Wang J, Sun X, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity and related comorbidities: a meta-analysis of 21 studies. Obes Surg. 2015;25:19–26. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641–651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang SH, Stoll CR, Song J, Varela JE, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003-2012. JAMA Ssurgery. 2013;149:275–287. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu J, Zhou X, Li L, et al. The long-term effects of bariatric surgery for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized evidence. Obes Surg. 2014;25:143–158. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial—a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273:219–234. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, et al. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HJ, Madan A, Fenton-Lee D. Does patient compliance with follow-up influence weight loss after gastric bypass surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2014;24:647–651. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trastulli S, Desiderio J, Guarino S, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy compared with other bariatric surgical procedures: a systematic review of randomized trials. Surgery Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:816–829. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panunzi S, de Gaetano A, Carnicelli A, Mingrone G. Predictors of remission of diabetes mellitus in severely obese individuals undergoing bariatric surgery: do BMI or procedure choice matter? A meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2014;26:459–467. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e. V. Das AWMF-Regelwerk Leitlinien. www.awmf.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Leitlinien/AWMF-Regelwerk/AWMF-Regelwerk.pdf(last accessed on 12 March 2018) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMETHODS: ON THE CREATION OF THE GUIDELINE

The guideline committee

As required by the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF), other specialty societies (i.e., societies other than the one mainly responsible for the guideline), corresponding to the intended users of the guideline, were included in the committee; a patient representative was included as well (etable 1). The conflict of interest statements submitted by all committee members, as required by the AWMF, are incorporated in the guideline report (5).

The literature search

The guideline was created in collaboration with the UserGroup—Medizinische Leitlinienentwicklung e. V., CGS Clinical Guideline Services, Berlin, and with the counseling and interactive support of the AWMF. The literature search and evaluation were carried out by the UserGroup—Medizinische Leitlinienentwicklung e. V. in collaboration with the guideline committee. On the basis of questions formulated according to the PICO scheme, and corresponding algorithms, a search for literature published from April 2009 to March 2016 was carried out in the Medline, Cochrane Library, and Scopus databases. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were sought.

Results of the literature search

The literature search yielded 9099 hits (after the elimination of duplicates), which were subjected to multilevel screening. 7920 were excluded by screening of titles and abstracts, leaving 1179 for full-text screening. 833 were excluded, leaving 353 publications that were intended to be used in the evaluation of the literature on all key questions. After correction for publications that were counted more than once because they were relevant to multiple key questions, and therefore appeared in multiple literature groups, the number remaining for evaluation was 261.

Evaluation of the evidence

The evidence was evaluated by the SIGN method (etable 2) (6). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were given priority. RCTs and cohort studies that were included in systematic reviews of good or very good quality were not individually evaluated. If two or more reviews overlapped in more than half of the studies that they included, only the review that was of the highest quality and had the most recent publication date was considered. In this way, the 261 publications chosen for analysis after full-text screening were reduced to a set of 56 systematic reviews and meta-analyses and, as requested by the experts, one RCT and five cohort studies.

PRISMA charts on the screening algorithm for the literature search on each topic, including reasons for the exclusion of publications, can be seen in the guideline report (eFigure) (5). In the next step, data were extracted from the included publications and summarized in the form of evidence tables.

Structured consensus-finding and formulation of the recommendations

After formulation of the guideline text and recommendations, the latter were evaluated and commented upon online in the framework of a formal consensus-finding process with two rounds of voting, then discussed a final time in the subsequent structured consensus conferences, where they were assigned recommendation grades (etable 3) and consensus strengths (etable 4).

The recommendation grades were assigned on the basis of the evidence, as well as further criteria such as the consistency of study findings, the clinical relevance of the endpoints and effect strengths, risk–benefit ratios, the applicability of the study findings to the target group of patients and to the healthcare system, the implementability of the recommendations in routine care, patient preferences, and ethical and legal aspects.

Recommendations that were not study-based were designated as “expert consensus.” These recommendations represent good clinical practice still in need of confirmation by scientific studies, or for which such confirmation cannot be expected because any relevant studies would be considered unethical.

The resulting guideline text was submitted to all participating specialty societies (and by some of these to their respective membership), discussed in multiple rounds, and amended as indicated. Compromises that were acceptable to the guideline committee could be found on all points, so that no special votes were necessary.