Abstract

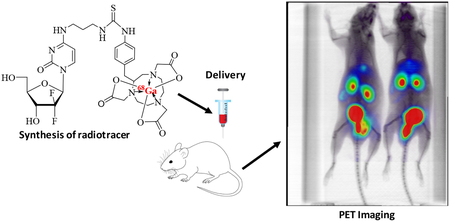

The conjugation of 4-N-(3-aminopropanyl)-2’-deoxy-2’,2’-difluorocytidine with 2-(p-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (SCN-Bn-NOTA) ligand in 0.1 M Na2CO3 buffer (pH 11) at ambient temperature provided 4-N-alkylgemcitabine-NOTA chelator. Incubation of latter with excess of gallium(III) chloride (GaCl3) (0.6 N AcONa/H2O, pH = 9.3) over 15 min gave gallium 4-N-alkylgemcitabine-NOTA complex which was characterized by HRMS. Analogous [68Ga]-complexation of 4-N-alkylgemcitabine-NOTA conjugate proceeded with high labeling efficiency (94% to 96%) with the radioligand almost exclusively found in the aqueous layer (~95%). The high polarity of the gallium 4-N-alkylgemctiabine-NOTA complex resulted in rapid renal clearance of the 68Ga-labelled radioligand in BALB/c mice.

Keywords: Nucleosides, Gemcitabine, Prodrugs, NOTA, PET imaging, 68-Gallium

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

Gemcitabine (2’-deoxy-2’,2’-difluorocytidine, dFdC) is a potent chemotherapeutic drug used in the treatment of cancers and solid tumors.1–2 Various prodrug strategies have been developed to improve uptake and to diminish intracellular deamination of gemcitabine into toxic 2’-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorouridine (dFdU) by deoxycytidine deaminase (dCDA).3 Most of these prodrugs possess lipophilic acyl modifications on the exocyclic 4-N-amine or 5’-hydroxyl groups.4–9 Gemcitabine analogues have also been designed as theranostic anticancer prodrugs with cellular specificity and imaging capabilities. These include H-gemcitabine10 and gemcitabine-coumarin-biotin conjugates,11 among others.12–13

Recently, 1-(2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-β-D-arabinofuranosyl)cytosine [18F-FAC] was developed as a noninvasive predictor probe of tumor response to gemcitabine.14–17 Although FAC generally follows the known biodistribution of gemcitabine, it is missing a geminal difluoromethylene unit at C2’, that is critical for anticancer properties of dFdC, its inhibitory activity of ribonucleotide reductases,18 and its physicochemical properties.19 Practical syntheses of gemcitabine are based on incorporation of a geminal difluoro unit into the ribose moiety in the early synthetic stages.20–21 Preparation of 2’-[18F]dFdC following these synthetic approaches would result in an impractical multistep radiosynthesis, given the short half-life of the 18F isotope (110 mins) and the lack of availability of the proper synthetic precursors.22 To address these challenges, we have explored developing gemcitabine radiotracers in which 18F labeling is incorporated at a different position than at sugar C2’ and in the later stages of their synthesis (Figure 1).

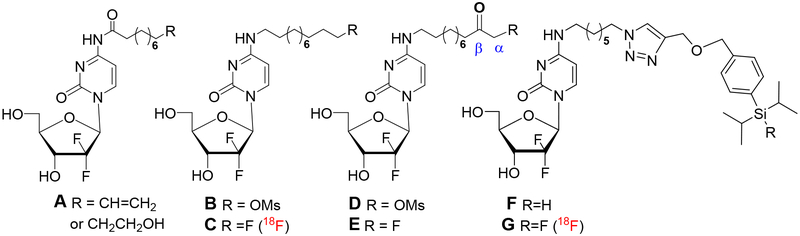

Figure 1.

The 4-N-acyl and 4-N-alkyl gemcitabine analogues suitable for 18F-radiolabelling.

We have developed 4-N-acyl gemcitabine analogues with modifications suitable for incorporation of fluorine radiotracers (e.g. A, Figure 1). However, 4-N-acyl analogues A showed cleavage of the amide linkage under typical radiosynthetic protocols for 18F labeling (KF/K2CO3/K2.2.2/CH3CN/110°C). We found, however, that 4-N-alkyl gemcitabine derivatives24 are suitable for incorporation of 18F radiolabels to 4-N-alkyl chain (e.g., B → C), yet showed 18F in vivo defluorination, which resulted in marked bone uptake as Na18F during mice studies.25 Subsequently, we explored lipophilic 4-N-alkyl gemcitabine analogues bearing terminal β-ketosulfonate (e.g. D) in which the lack of hydrogen at carbon β was expected to prevent loss of fluorine. However, fluorination and deprotection under conditions required for 18F labeling afforded fluoro product E in low yields.26 We recently also reported 4-N-acyl and 4-N-alkyl gemcitabine analogues with silicon-fluoride moieties that have shown to be good substrates for 18F-labeling (e.g., F → G). Preliminary positron-emission tomography (PET) imaging in mice showed the biodistribution of [18F]-G to have initial concentration in the liver, kidneys and GI tract followed by increasing signal in the bone.27

Hydrolysis of the 4-N-amide linkage under radiosynthetic protocols employed in the preparation of 18F radiotracers and observed early loss of 18F through the elimination processes during in vivo mice studies prompted us to search for other gemcitabine conjugates suitable for PET imaging. Recent advances in aza-crown ethers bifunctional chelators with the ability to bind gallium generated significant interest in 68Ga-based radiopharmaceuticals28–32 and radiotracers.33–34 As a metal salt, gallium has been reported to possess anti-proliferative properties in various cancer cells mainly attributed with its ability to mimic Fe3+.35–37 Among bifunctional chelators, NODA-SA38 (1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1-succinic acid-4,7-diacetic acid) and NODA-GA39 (1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1-glutamic acid-4,7-diacetic acid), which possess a NOTA (1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid) complexation site, have a coordination cavity highly accommodating to Ga(III) (ionic radius, 0.65 Ǻ). Also, anti-TF (Tissue Factor) antibody (ALT-836) conjugated to 4-isothiocyanatobenzyl-NOTA (SCN-Bn-NOTA) labelled with 64Cu showed uptake in pancreatic cancer cells overexpressing TF and has been advanced to Phase I clinical trials as a combination therapy with gemcitabine.40 These results encouraged us to investigate 4-N-alkanoyl/alkyl gemcitabine analogues conjugated with aza-crown ether chelators for 68Ga-labelling.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. 4-N-Alkanoyl gemcitabine-NOTA conjugates

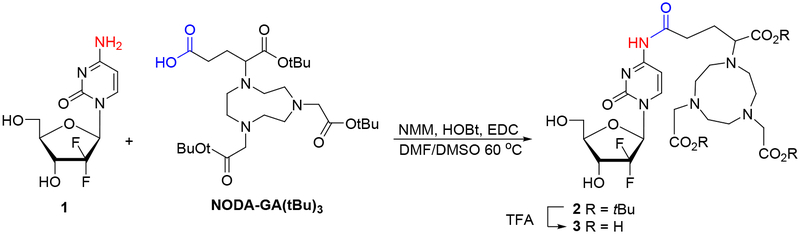

Initially, we attempted direct condensation of gemcitabine 1 with commercially available NODAGA(tBu)3 using conditions previously employed for coupling of the weakly nucleophilic 4-amino group of gemcitabine with carboxylic acids.23 Thus, condensation of 1 with NODA-GA(tBu)3 in the presence of N-methylmorpholine (NMM), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC) gave protected NODA - 4-N-alkanoylgemcitabine conjugate 2 in only 10% yield after RP-HPLC purification (Scheme 1). Nevertheless 2 was found to be unstable and upon standing slowly decomposed back to 1. Deprotection of 2 with TFA afforded NODA-GA-4-N-alkanoylgemcitabine conjugate 3 (37%) but also promoted further decomposition to 1. Moreover, coupling of 1 with 2-(p-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (SCN-Bn-NOTA) in 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer (pH = 9.5)33 failed to produce the corresponding thiourea conjugate.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the 4-N-alkanoyl gemcitabine-NOTA conjugate.

In an effort to overcome the poor nucleophilicity associated with cytosine’s exocyclic amine, we also explored gemcitabine analogues having a more nucleophilic primary amine at the 4-N-alkanoyl linker for subsequent conjugation with NOTA chelators. Thus, condensation of 1 with commercially available N-Boc-β-alanine (NMM/HOBt/EDC) provided 4a in 65% yield (Scheme 2). Attempted removal of the Boc protection at 4-N-(3-aminopropanoyl) linker in 4a with TFA was problematic to control and led mainly to the cleavage of the amide linkage yielding gemcitabine 1 in addition to desired 4b in very low yields.41 Besides, condensation of the crude 4b with SCN-Bn-NOTA in 0.1 M Na2CO3 (pH = 11) over 14 h was unsuccessful to provide a stable gemcitabine-NOTA ligand 5.

Scheme 2.

Attempted synthesis of gemcitabine-NOTA conjugate with 4-N-alkanoyl linker

2.2. 4-N-Alkyl gemcitabine-NOTA conjugates

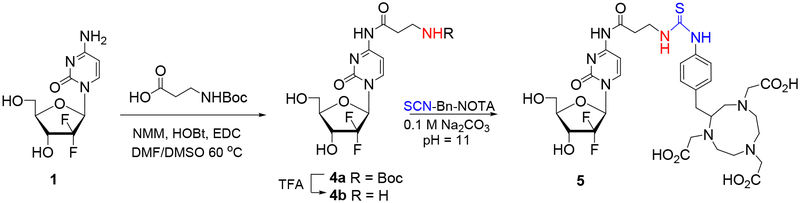

Since 4-N-alkylgemcitabine derivatives are resistant to chemical hydrolysis as well as enzymatic deamination by cytidine deaminase,23 we next undertook an effort to prepare gemcitabine-NOTA ligand conjugated via 4-N-alkyl linker. The 4-N-tosylgemcitabine 6a (prepared from gemcitabine in 96% yield23) and 3’,5’-di-O-Boc protected 4-N-tosylgemcitabine 6b23 served as convenient substrates. Displacement of the p-toluenesulfonamido group from 6b with commercially available N-Boc-1,3-propanediamine in 1,4-dioxane afforded as main product the partially deprotected 4-N-(3-N’-Boc-3-aminopropanyl)gemcitabine 7 (59%, Scheme 3) in addition to 3’,5’-di-O-Boc protected product (31%). Subsequent deprotection of 7 with TFA yielded the 4-N-(3-aminopropanyl) derivative 8 (93%), with a primary amine group suitable for coupling with ligands. Amine 8 was also prepared efficiently in a “one-pot” synthesis from 6a (94% overall yield) without isolation of 7.

Scheme 3.

Preparation of the gemcitabine-NOTA conjugate with 4-N-alkyl linker.

Condensation of 8 with commercially available SCN-Bn-NOTA in 0.1 M Na2CO3 buffer (pH = 11) at ambient temperature for 48–72 h afforded the 4-N-(3-SCN-Bn-NOTA-propanyl)gemcitabine conjugate 9 identified by HRMS (ESI+) m/z 771.2879. The 4-N-alkylgemcitabine-NOTA conjugate 9 was found to be stable as a solid, however some minor deterioration back to 8 (TLC/HPLC) was observed after some time (few weeks) even when stored at −20°C. This showed again that gemcitabine analogues with 4-N-alkyl chains have better stability that the corresponding 4-N-acyl counterparts (e.g., 2 or 5).

2.3. [68Ga]-Labeling and evaluation of NOTA-4-N-alkylgemcitabine radioligand.

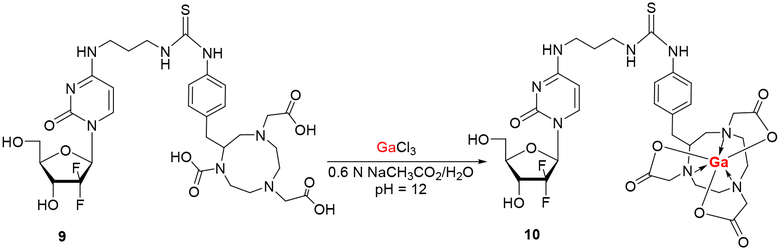

Incubation of 9 with excess of gallium(III) chloride (GaCl3) mimicking radiosynthetic conditions (0.6 N AcONa/H2O, pH = 9.3) over 15 min gave the gallium NOTA-4-N-alkylgemctiabine complex 10, characterized by HRMS (ESI+) m/z 837.1977 (Scheme 4). The reaction products were isolated by HPLC on a Phenomenex Gemini semi-preparative RP-C18 column [0% → 100% ethanol gradient in 0.01% TFA/H2O from 0 to 30 min at a flow rate = 3 mL/min] giving 9 (tR = 12.8 min) and 10 (tR = 11.5 min), respectively. The gallium complexation met criteria for working with [68Ga]3+ (half-life 68 min) and was applied towards the radiosynthesis of the [68Ga]-10 radioligand.

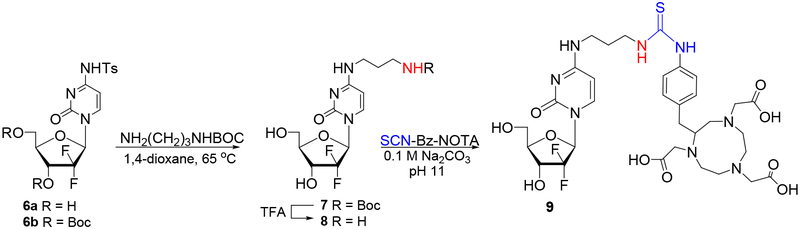

Scheme 4.

Labeling of 4-N-alkylgemcitabine-NOTA conjugate with gallium or 68Ga.

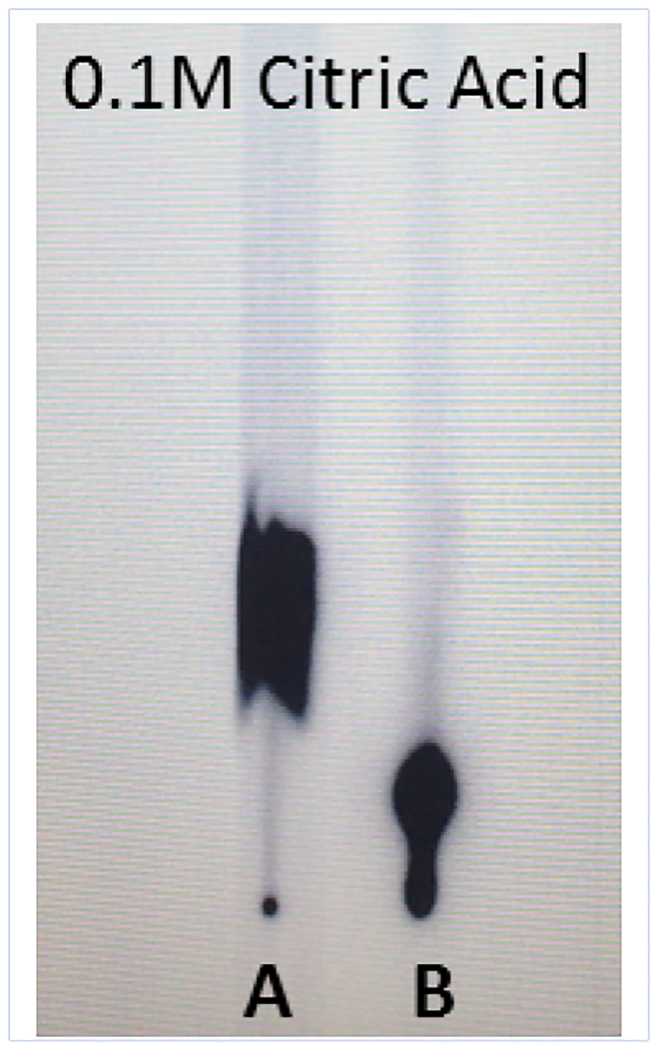

The 68Ga was eluted from an IGG-100 68Ge/68Ga generator. Purified [68Ga]+3 (10 mCi in 1 mL of ≈0.1 N HCl) for the labeling was obtained following previously elaborated conditions.42 The [68Ga]-labeling of 9 was completed within 15 min and analyzed by developing TLC plates eluted with 0.1 M citric acid on a phosphoscreen (Figure 2). Phosphoscreen analysis (Table 1) indicated a high labeling efficiency (94% to 96%) for the complexation of the NOTA-4-N-alkylgemcitabine 9 with [68Ga]3+ to yield [68Ga]-10.

Figure 2.

TLC for complexation of NOTA-4-N-alkylgemcitabine 9 with 68Ga. Free [68Ga]3+ (lane A) and [68Ga]-complexed-10 (lane B).

Table 1.

Labeling values for 4-N-alkylgemcitabine-NOTA ligand 9 with 68Ga.

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (Free 68Ga) | Cmpd [68Ga]-10 | Control (Free 68Ga) | Cmpd [68Ga]-10 | Control (Free 68Ga) | Cmpd [68Ga]-10 | |

| Counts in upper | 363069018 | 25232330 | 240306449 | 10064331 | 219716549 | 6458287 |

| region Counts in lower | 7970885 | 374787348 | 4208914 | 256461215 | 3319270 | 166566169 |

| Region Labeling Yield | ≈ 2% Appl. Point | 94% | ≈ 2% Appl. Point | 96% | ≈ 1% Appl. Point | 96% |

The distribution coefficient of [68Ga]-radioligand 10 was evaluated in octanol/H2O and EtOAc/H2O. The radioligand 10 was almost exclusively found in the aqueous layer, with less <5% of the observed counts occurring in the organic phase (data not shown) of either system. The hydrophilic character of [68Ga]-radioligand 10 suggests that the radioligand will be rapidly excreted.

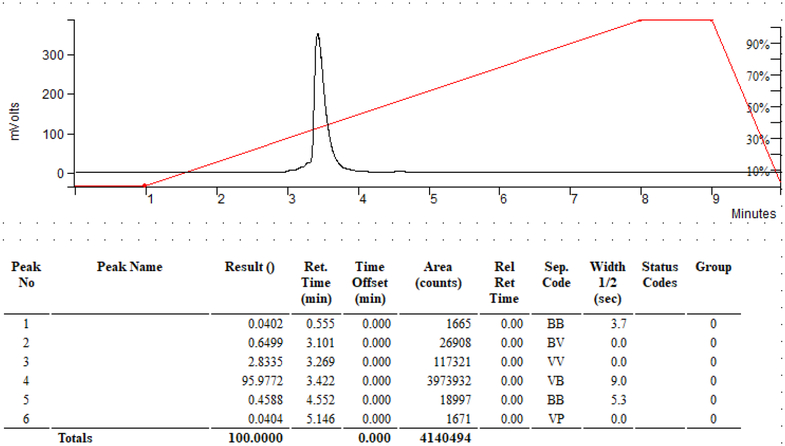

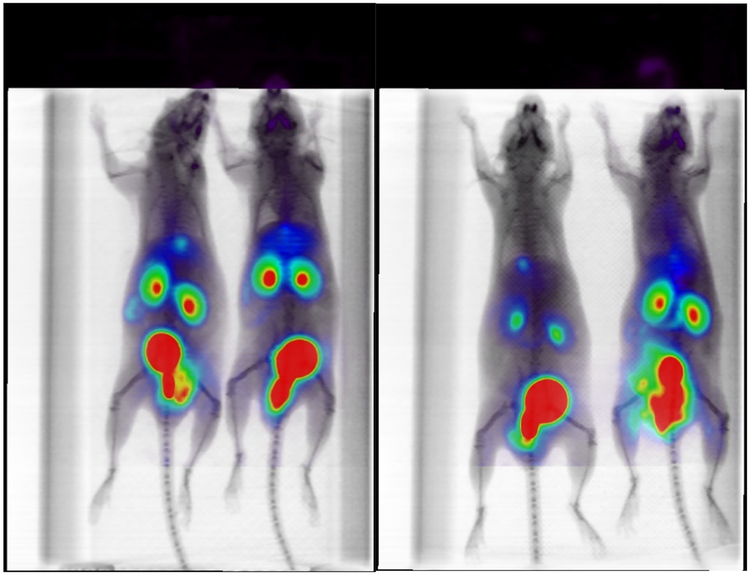

Labeling of 9 with 68Ga was repeated to test for distribution of 10 in BALB/c mice. Chelation of 68Ga to NOTA moiety in 9 was quantitative after 5 minutes incubation. However, a shoulder and some minor impurities peaks were observed. The purity did not change after Sep-Pak purification, showing a shoulder (RT: 3.27 min) and a minor peak (RT: 4.55 min) that are still visible and quantifiable (Figure 3). However, these impurities were not expected to have a large effect on imaging studies. only minimal hepatobiliary excretion during in vivo mice studies. The rapid renal clearance of [68Ga]-10 is most likely due to the increased hydrophilicity caused by the addition of the NOTA chelator as compared to 18F-FAC14 or more hydrophobic 18F radiolabeled 4-N-alkyl gemcitabine analogues C25 and G27 (see Figure 1). Although not within the scope of the present work, this compound could result in higher contrast images due to higher lesion to background ratio, which could produce significant clinical impact. The one hour post-injection images are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

HPLC purification of [68Ga]-10 with minor impurities after Sep-Pak purification. Interestingly, in contrast with previously published studies with 18F-FAC,14 compound [68Ga]-10 showed

Figure 4.

BALB/c maximum intensity projection (MIP) μPET/CT mice images at one hour post injection showing rapid renal clearance.

In conclusion, we have developed the synthesis of 4-N-alkyl gemcitabine−NOTA conjugates and their efficient complexation with gallium that provides the basis for development of the 4-N-modified gemcitabine derivatives, bearing an elongated alkyl chains with more lipophilic character, as potential 68-gallium PET imaging radioligands.

3. Experimental

The 1H (400 MHz), 13C (100 MHz), or 19F (376 MHz) NMR spectra were recorded at ambient temperature in MeOH-d4, unless otherwise noted. The reactions involving non-radioactive materials were followed by TLC with Merck Kieselgel 60-F254 sheets and products were detected with a 254 nm UV lamps. Column chromatography was performed using Merck Kieselgel 60 (230–400 mesh). Perkin Elmer high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used for purifying both the non-complexed and complexed compounds on RP-C18 semi-preparative Phenomenex Gemini or preparative XTerra columns with mobile phase and flow rate as indicated. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained with a Solarix instrument (FT-MS). The SCN-Bn-NOTA and NODA-GA(tBu)3 bifunctional chelators were purchased from Macrocyclics Inc, TX, USA and CheMatech, Dijon, France, respectively. Gemcitabine hydrochloride was purchased from LC Laboratories, MA, USA. All other reagent grade chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

4-N-[4-(4,7-Bis(2-tert-butoxy-2-oxoethyl)-1,4,7-triazonan-1-yl)-5-tert-butoxy-5-oxopentanoyl]-2’-deoxy-2’,2’-difluorocytidine (2).

Gemcitabine 1 (12.6 mg, 0.042 mmol) was treated with 4-(4,7-bis(2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethyl)-1,4,7-triazacyclononan-1-yl)-5-(tert-butoxy)-5-oxopentanoic acid [NODA-GA(tBu)3; 25 mg, 0.046 mmol] according to coupling conditions as described for 4a. After 20 h, reaction mixture was treated with H2O and EtOH, the volatiles evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue (75 mg) diluted with a solution of 95% H2O/CH3CN to a total volume of 1.5 mL, passed through a 0.2 μm PTFE syringe filter and then injected into a preparative HPLC column (XTerra Prep RP-C18 column; 5μ, 19 × 150 mm) via 2 mL loop. The HPLC column was eluted with a gradient program (isocratic mobile phase mixture 95% H2O/CH3CN for 60 min, gradient 95 → 0% H2O/CH3CN over 30 min) at a flow rate = 2.5 mL/min, to give 2 (3.4 mg, 10%; tR = 100–125 min) as a clear oil: 1H NMR δ 1.44–1.53 (m, 27H, 9 × CH3), 1.58–1.67 (m, 2H), 1.90–2.03 (m, 2H), 2.05–2.12 (m, 2H), 2.68–2.75 (m, 2H), 2.76–3.05 (m, 13H), 3.80–3.88 (m, 1H, H5’), 3.97–4.03 (m, 2H, H4’, H5”), 4.26–4.36 (m, 1H, H3’), 6.28 (“t”, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, H1’), 7.52 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.22 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 19F NMR δ −119.03 (d of m, J = 246.1 Hz, 1F), −120.09 (d of m, J = 247.4 Hz, 1F); MS (ESI) m/z 789 (100, [M+H]+).

4-N-[4-(4,7-Bis(carboxymethyl)-1,4,7-triazonan-1-yl)-4-carboxybutanoyl]-2’-deoxy-2’,2’-difluorocytidine (3).

Compound 2 (3.4 mg, 0.004 mmol) was dissolved in TFA (1.0 mL) and the mixture was stirred at ambient temperature overnight. After 15 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with toluene, the volatiles were evaporated, and the residue co-evaporated with a fresh portion of toluene. The resulting residue was then dissolved with a solution of 95% H2O/CH3CN to a total volume of 1.5 mL, passed through a 0.2 μm PTFE syringe filter and then injected into a preparative HPLC column (XTerra Prep RP-C18 column; 5μ, 19 × 150 mm) via 2 mL loop. The HPLC column was eluted with a gradient program (isocratic mobile phase mixture 95% H2O/CH3CN for 60 min, gradient 95 → 0% H2O/CH3CN over 30 min) at a flow rate = 2.5 mL/min, to give 3 (1.0 mg, 37%; tR = 63–70 min) as a clear oil: 1H NMR (D2O) δ 1.78–1.95 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.33–2.38 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.97–3.02 (m, 5H), 3.04–3.09 (m, 6H), 3.11–3.16 (m, 5H), 3.37–3.43 (m, 1H), 3.60–3.67 (m, 1H, H5’), 3.75–3.82 (m, 1H, H5”), 3.84–3.88 (m, 1H, H4’), 4.08–4.16 (m, 1H, H3’), 5.96 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H5), 5.99 (“t”, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H1’), 7.67 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H6); 19F NMR (D2O) δ −117.39 (d of m, J = 230.5 Hz, 1F), −117.71 (d of m, J = 236.1 Hz, 1F); MS (ESI) m/z 621 (100, [M+H]+).

4-N-[3-N-(tert-Butoxycarbonyl)-3-aminopropanoyl]-2’-deoxy-2’,2’-difluorocytidine (4a).

N-Methylmorpholine (NMM; 15.6 mg, 0.154 mmol), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt; 20.8 mg, 0.169 mmol), commercially available N-Boc-β-alanine (29.2 mg, 0.154 mmol) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC; 28.3 mg, 0.182 mmol) were sequentially added to a stirred solution of gemcitabine hydrochloride (1; 42 mg, 0.140 mmol) in DMF/DMSO (3:1, 2 mL) at ambient temperature under Argon. The reaction mixture was then gradually heated to 65°C (oil-bath) and kept stirring overnight. After the reaction was completed (TLC), the reaction mixture was cooled to 15°C and partitioned between a small amount of brine and EtOAc. The organic phase was separated, and the aqueous layer extracted with fresh portions of EtOAc (2 × 10 mL). The combined organic layers were then washed with NaHCO3/H2O, dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated. The crude product was column chromatographed (5% MeOH/EtOAc) to give 4a (40.1 mg, 65%) as a white solid: 1H NMR δ 1.42 (s, 9H, 3 × CH3), 2.63 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.37 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.81 (dd, J = 3.2, 12.8 Hz, 1H, H5’), 3.95–3.99 (m, 2H, H4’, H5”), 4.24–4.34 (m, 1H, H3’), 6.26 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, H1’), 7.49 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.33 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 19F NMR δ −121.01 (br. d, J = 237.0 Hz, 1F), −119.16 (dd, J = 243.4, 12.1 Hz, 1F); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C17H25F2N4O7 [M+H]+, 435.1686, found 435.1699.

4-N-[3-N-(tert-Butoxycarbonyl)-3-aminopropanyl]-2’-deoxy-2’,2’-difluorocytidine (7).

In a tightly sealed vessel, a mixture of 6b23 (11.5 mg, 0.018 mmol) and commercially available N-Boc-1,3-propanediamine (150 μL, 150 mg, 0.86 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane was stirred at 65°C. After 48 h, the volatiles were evaporated the resulting residue was column chromatographed (30% EtOAc/hexane → 5% MeOH/EtOAc) to give fully protected 3’,5’-di-O-Boc-4-N-(3-N’-Boc-3-aminopropanyl)gemcitabine [3.6 mg, 31%; MS (ESI+) m/z 621 (100, [M+H]+)] followed by 7 (3.5 mg, 59%) as colorless oil: 1H NMR δ 1.43 (s, 9H, 3 × CH3), 1.74 (“quint”, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.10 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.41 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.77 (dd, J = 3.2 Hz, 12.6 Hz, 1H, H5’), 3.87 (dt, J = 2.8, 8.3 Hz, 1H, H4’), 3.93 (“d,” J = 2.1, 12.6 Hz, 1H, H5”), 4.24 (dt, J = 8.4, 12.1 Hz, 1H, H3’), 5.85 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 6.21 (“t,” J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, H1’), 7.75 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 19F NMR δ −119.94 (br. d, J = 240.6 Hz, 1F), −118.83 (dd, J = 10.3, 238.3 Hz, 1F); MS (ESI) m/z 421 (100, [M+H]+).

4-N-(3-Aminopropanyl)-2’-deoxy-2’,2’-difluorocytidine (8).

Method A.

Compound 7 (3.4 mg, 0.008 mmol) was dissolved in TFA (1.0 mL) and the mixture was stirred at ambient temperature overnight. After 15 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with toluene, the volatiles were evaporated, and the residue co-evaporated with a fresh portion of toluene. The resulting residue was then column chromatographed [EtOAc → 50% EtOAc/SSE (EtOAc/i-PrOH/H O, 4:2:1; upper layer)] to give 8 (2.4 mg, 93%) as a white solid: 1H NMR δ 1.95 (“quint”, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.19 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.51–3.57 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.81 (dd, J = 3.1, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H5’), 3.91–3.99 (m, 2H, H4’, H5”), 4.28 (dt, J = 8.2, 12.1 Hz, 1H, H3’), 5.92 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H5), 6.25 (“t,” J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H1’), 7.88 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, H6); 13C NMR δ 34.7, 38.6, 39.1, 60.5 (C5′), 70.1 (dd, J = 21.0, 24.2 Hz, C3′), 82.8 (dd, J = 4.1, 5.1 Hz, C4′), 86.2 (C1), 97.8 (C5), 125.0 (t, J = 256.8 Hz, C2′), 140.1 (C6), 158.9 (C2), 165.9 (C4). 19F NMR δ −118.92 (br. d, J = 241.2 Hz, 1F), −120.11 (dd, J = 10.4, 237.8 Hz, 1F); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C12H19F2N4O4 [M+H]+, 321.1369, found 321.1346.

Method B.

In a tightly sealed container, a solution of 6a23 (19.6 mg, 0.048 mmol), commercially available N-Boc-1,3-propanediamine (100 μL, 100 mg, 0.58 mmol) and TEA (3 mL) in 1,4-dioxane was stirred at 75°C. After 96 h, the volatiles were evaporated and the resulting residue was treated with TFA (1.5 mL) and the mixture stirred at ambient temperature overnight. After 15 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with toluene, the volatiles were evaporated, and the residue co-evaporated with a fresh portion of toluene. The resulting residue was then column chromatographed (10% MeOH/EtOAc) to give 8 (15.6 mg, 94%) with data as reported above.

4-N-[3-N-(SCN-Bn-NOTA)aminopropanyl]-2’-deoxy-2’,2’-difluorocytidine (9).

A mixture of SCN-Bn-NOTA (10 mg, 0.031 mmol) and 8 (10 mg, 0.018 mmol) in 3 mL of 0.1 M Na2CO3 buffer (pH 11) was stirred at ambient temperature for 60 h. The reaction mixture was injected into a Phenomenex Gemini semi-preparative RP-C18 column (5μ, 25 cm × 1 cm) via 2 mL loop and eluted with 0% → 100% ethanol gradient in 0.01% TFA/H2O from 0 to 30 min at a flow rate = 3 mL/min. Product 9 (12.5 mg, 54% yield) eluted with rt = 12.8 min. 1H NMR δ 1.90 (“quint”, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.68–2.75 (m, 2H), 2.87–2.95 (m, 4H), 3.06–3.15 (m, 3H), 3.17–3.29 (m, 5H), 3.41–3.48 (m, 4H), 3.50–3.62 (m, 1H), 3.65–3.72 (m, 4H), 3.79 (dd, J = 3.2 Hz, 12.5 Hz, 1H, H5”), 3.88–3.98 (m, 2H, H4, H5’), 4.20–4.29 (m, 1H, H3’), 5.89 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 6.26 (“t”, J = 8.0 Hz, H1’), 7.22–7.28 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.31–7.37 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.79 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6). 19F NMR δ −118.80 (d of m, J = 242.1 Hz, 1F), −119.45 (d of m, J = 244.1 Hz, 1F). MS (ESI+) m/z 771 (100, [M+H]+); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C32H45F2N8O10S [M+H]+ 771.2942; found 771.2879.

Gallium 4-N-[3-N-(SCN-Bn-NOTA)aminopropanyl]-2’-deoxy-2’,2’-difluorocytidine (10).

Gallium(III) chloride (5.1 mg, 0.029 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of 9 (1.0 mg, 0.001 mmol) in 0.6 N NaCH3CO2/H2O (1 mL, pH = 9.3) at ambient temperature. After 30 min, the reaction was diluted to a total volume of 1.5 mL with H2O and injected into a Phenomenex Gemini semi-preparative RP-C18 column (5μ, 25 cm × 1 cm) via 2 mL loop and eluted with 0 → 100% ethanol gradient in 0.01% TFA/H2O from 0 to 30 min at a flow rate = 3 mL/min. Product 10 (0.5 mg, 46% yield) eluted with tR = 11.5 min. HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C32H42F2GaN8NaO10S [M+H]+ 837.1963; found 837.1977.

Generation of 68Ga radiotracer of 10.

68Ge/68Ga Radioisotopic Generator:

Two different 68Ge/68Ga generators were used in this study, a 50 mCi IGG-100 (Eckert & Ziegler, Germany), based on the TiO2 resin technology; and a 50 mCi ITG generator (ItM, Germany), based on a modified silica resin.

Labeling with IGG-100 68Ge/68Ga Generator:

The generator was eluted with 5 mL of 0.1 M ultrapure HCl (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) solution. Since the elution contains metal contaminants, a combination of chromatographic exchange resins were used for pre-purification of the eluent as described previously.42 Briefly, two luer-fitting column beds were prepared. First, 40 mg of AG-50Wx8 cation exchange (Eichrom, USA) column was connected to a three-way stopcock. Next, 15 mg of UTEVA anion exchange (Eichrom, USA) resin in a column was positioned. Finally, another three-way stopcock was located at the end. The system was designed to be used in four simple steps: elution (from the generator, 5mL of 0.1 M HCl); cleaning (1 mL of 0.1 M HCl); purification (1 mL of 5 M HCl); extraction (1 mL of Millipore Water).

The purified 68Ga elution (1 mL, pH = 0.6–1; activity = 10–20 mCi) obtained from the purification system was collected in a 15 mL centrifuge tube. A solution containing 9 (10 μg of a 1 mg/ml solution in DMSO) was later added and immediately buffered using 0.3 mL of 3 N ultrapure sodium acetate (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Labeling was performed using a thermomixer stirring at 750 rpm for 15 minutes at room temperature (Eppendorf, Germany), taking samples at 5, 10 and 15 minutes of incubation. No further purification was done for initial testing. Final quality control was performed in Silicagel 60 TLC plates with 0.1 M citric acid as the mobile phase. Plates were quantified in OptiQuant software (Perkin Elmer, USA) by exposing a phosphoscreen for 5 min and reading it in a Packard Cyclone Phosphorimager (Perkin Elmer, USA). This labeled product was not used for imaging.

Labeling with the ITG 68Ge/68Ga Generator:

This generator was eluted using 4 ml of 0.05M HCl and collected in a 15 ml sterile centrifuge tube. The obtained solution containing up to 1850 MBq (50 mCi) of 68Ga was directly used for labeling by adding 25 μl of a 1 mg/ml compound 9 stock solution in DMSO, followed by 80 μl of a 3N NaOAc solution for buffering (pH = 4–5). The mixture was then placed in a thermomixer (FisherSci, USA) at 95°C and 750 rpm shaking for 15 minutes. A sample of the reaction was taken and analyzed by radio HPLC to confirm the labeling. Immediately after labeling confirmation, a purification/reformulation was performed by trapping the labeled product in a C-18 Sep-Pak Plus Lite (Waters, USA) followed by a wash with 5 ml of saline solution. The product was then eluted with 200 μl of a 50 % EtOH/saline solution, followed by 0.9 ml of saline to produce a final injectable solution containing 8–9% EtOH in 1 ml saline. A final QC HPLC was performed to assess purity.

Quality Control:

Radiochemical and chemical purity were determined on a dual pump Varian Dynamax HPLC (Agilent Technologies, USA) fitted with an Agilent ProStar 325 Dual Wavelength UV-Vis Detector and a NaI(Tl) flow count detector (Bioscan, USA). UV absorption was monitored at 220 nm and 280 nm. Solvent A was 0.01 % trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in H2O and solvent B was 0.01 % TFA in 90:10 v/v MeCN:H2O. Analytical (radio)HPLC was performed a Symmetry® C18, 4.6×50 mm column (Waters, USA), a flow rate of 2 mL/min and a gradient of 0% B 0–1 min., 0–100% B 1–8 min and 100–0% B 8–10 min. Compound identity was confirmed by co-injection with known standards.

Imaging:

Animals (BALB/c) were injected with 100 μl of the final solution and placed immediately in the camera under 2% isoflurane anesthesia. Imaging was performed in a Siemens Inveon μPET/CT for 30 min from 45 to 75 minutes post injection. Final Maximum Intensity Projection (MIP/μPET CT) images are presented for 4 animals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This investigation was partially supported by award SCICA13876 from NIGMS and NCI (SFW). Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) graduate fellowship recipient Maria de Cabrera was supported by the NRC fellowships grants NRC-HQ-84–14-G-0040 and NRC-HQ-84–15-G-0038 to Florida International University (FIU).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References and notes:

- (1).Gesto DS; Cerqueira NM; Fernandes PA; Ramos MJ Curr. Med. Chem 2012, 19, 1076–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Jordheim LP; Durantel D; Zoulim F; Dumontet C Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2013, 12, 447–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Veltkamp SA; Pluim D; van Eijndhoven MA; Bolijn MJ; Ong FH; Govindarajan R; Unadkat JD; Beijnen JH; Schellens JH Mol. Cancer Ther 2008, 7, 2415–2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Immordino ML; Brusa P; Rocco F; Arpicco S; Ceruti M; Cattel LJ Control Release 2004, 100, 331–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Couvreur P; Stella B; Reddy LH; Hillaireau H; Dubernet C; Desmaële D; Lepêtre-Mouelhi S; Rocco F; Dereuddre-Bosquet N; Clayette P; Rosilio V; Marsaud V; Renoir J-M; Cattel L Nano Letters 2006, 6, 2544–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Bender DM; Bao J; Dantzig AH; Diseroad WD; Law KL; Magnus NA; Peterson JA; Perkins EJ; Pu YJ; Reutzel-Edens SM; Remick DM; Starling JJ; Stephenson GA; Vaid RK; Zhang D; McCarthy JR J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 6958–6961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Bergman AM; Adema AD; Balzarini J; Bruheim S; Fichtner I; Noordhuis P; Fodstad O; Myhren F; Sandvold ML; Hendriks HR; Peters GJ Invest. New Drugs 2011, 29, 456–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Moysan E; Bastiat G; Benoit JP Mol. Pharm 2013, 10, 430–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Skilling KJ; Stocks MJ; Kellam B; Ashford M; Bradshaw TD; Burroughs L; Marlow M ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 1098–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Dasari M; Acharya AP; Kim D; Lee S; Lee S; Rhea J; Molinaro R; Murthy N Bioconjug. Chem 2013, 24, 4–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Maiti S; Park N; Han JH; Jeon HM; Lee JH; Bhuniya S; Kang C; Kim JS J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 4567–4572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Yang Z; Lee JH; Jeon HM; Han JH; Park N; He Y; Lee H; Hong KS; Kang C; Kim JS J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 11657–11662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Liu L-H; Qiu W-X; Li B; Zhang C; Sun L-F; Wan S-S; Rong L; Zhang X-Z Adv. Funct. Mater 2016, 26, 6257–6269. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Radu CG; Shu CJ; Nair-Gill E; Shelly SM; Barrio JR; Satyamurthy N; Phelps ME; Witte ON Nat. Med 2008, 14, 783–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Laing RE; Walter MA; Campbell DO; Herschman HR; Satyamurthy N; Phelps ME; Czernin J; Witte ON; Radu CG Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2009, 106, 2847–2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lee JT; Campbell DO; Satyamurthy N; Czernin J; Radu CG J. Nucl. Med 2012, 53, 275–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kim W; Le TM; Wei L; Poddar S; Bazzy J; Wang X; Uong NT; Abt ER; Capri JR; Austin WR; Van Valkenburgh JS; Steele D; Gipson RM; Slavik R; Cabebe AE; Taechariyakul T; Yaghoubi SS; Lee JT; Sadeghi S; Lavie A; Faull KF; Witte ON; Donahue TR; Phelps ME; Herschman HR; Herrmann K; Czernin J; Radu CG Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2016, 113, 4027–4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Artin E; Wang J; Lohman GJS; Yokoyama K; Yu G; Griffin RG; Bar G; Stubbe J Biochemistry 2009, 48, 11622–11629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Adhikary A; Kumar A; Rayala R; Hindi RM; Adhikary A; Wnuk SF; Sevilla MD J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 15646–15653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hertel LW; Kroin JS; Misner JW; Tustin JM J. Org. Chem 1988, 53, 2406–2409. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Brown K; Dixey M; Weymouth-Wilson A; Linclau B Carbohydr. Res 2014, 387, 59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Synthesis of 2’-[18F]-labelled gemcitabine from the protected 2’-ketouridine or 2’-ketocytidine employing deoxodifluorination method with DAST/[18F]fluoride/K222 were attempted but gave mono 18F-labeled gemcitabine in very low radiochemical yield (0.2–0.3%) and reproducibility:Meyer JP Synthetic Routes to 18F-labelled gemcitabine and related 2’-fluoronucleosides Ph.D., Cardiff University, 2014

- (23).Pulido J; Sobczak AJ; Balzarini J; Wnuk SF J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 191–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lipophilic 4-N-alkyl gemcitabine analogues lack hydrolysis in the cell and are not substrate for deoxycytidine kinase (dCK); thus they have lower anticancer activity than their 4-N-acyl counterparts. Also, 4-N-alkyl modified gemcitabine does not undergo deamination by deoxycytidine deaminase (DCA) into toxic derivatives. Because of the stability of the 4-N-alkyl chain, such analogues may be good candidates as 18F-PET radiotracers.

- (25).Pulido J Design and Synthesis of 4-N-Alkanoyl and 4-N-Alkyl Gemcitabine Analogues Suitable for Positron Emission Tomography. Ph. D., Florida International University, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Gonzalez C; de Cabrera M; Wnuk SF Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2018, 37, 248–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Gonzalez C; Sanchez A; Collins J; Lisova K; Lee JT; Michael van Dam R; Alejandro Barbieri M; Ramachandran C; Wnuk SF Eur. J. Med. Chem 2018, 148, 314–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Velikyan I; Maecke H; Langstrom B Bioconjug. Chem 2008, 19, 569–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Brechbiel MW Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Im 2008, 52, 166–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Notni J; Pohle K; Wester HJ EJNMMI Res 2012, 2, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Banerjee SR; Pomper MG Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 2013, 76, 2–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Farber SF; Wurzer A; Reichart F; Beck R; Kessler H; Wester HJ; Notni J ACS Omega 2018, 3, 2428–2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Jeong JM; Hong MK; Chang YS; Lee YS; Kim YJ; Cheon GJ; Lee DS; Chung JK; Lee MC J. Nucl. Med 2008, 49, 830–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Eder M; Schafer M; Bauder-Wust U; Hull WE; Wangler C; Mier W; Haberkorn U; Eisenhut M Bioconjug. Chem 2012, 23, 688–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Hedley DW; Tripp EH; Slowiaczek P; Mann GJ Cancer Res 1988, 48, 3014–3018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Chitambar CR; Narasimhan J; Guy J; Sem DS; O’Brien WJ Cancer Res 1991, 51, 6199–6201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Haq RU; Wereley JP; Chitambar CR Exp Hematol 1995, 23, 428–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Andre JP; Maecke HR; Zehnder M; Macko L; Akyel KG Chem. Commun 1998, 1301–1302. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Eisenwiener KP; Prata MIM; Buschmann I; Zhang HW; Santos AC; Wenger S; Reubi JC; Macke HR Bioconjug. Chem 2002, 13, 530–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Hong H; Zhang Y; Nayak TR; Engle JW; Wong HC; Liu B; Barnhart TE; Cai WB J. Nucl. Med 2012, 53, 1748–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Also, analogous coupling of 1 with N-Fmoc-β-alanine followed by deprotection with piperidine failed to give desired 4b in practical yields.

- (42).Amor-Coarasa A; Milera A; Carvajal D; Gulec S; McGoron AJ Int. J. Mol. Imag 2014, 2014, pp 7; doi:10.1155/2014/269365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.