The increased integration of Health Information Technology (HIT) [1] into our healthcare system has increased usage of electronic prescriptions (e-prescriptions). From 2008 to 2014, e-prescriptions usage rose from 7% to 70% [2]. However, debate exists regarding the enforced use of e-prescriptions. In March 2016, New York became the first state to ban all non-electronic prescriptions, with a threatened penalty of fines and imprisonment for non-complying physicians [3–5]. Although not currently enforced, physicians are concerned about its potential effect on patient care by reducing medication acquisition/compliance when pharmacies are closed or a medication is out of stock [4,6].

This study aimed to determine whether emergency department (ED) patients are more likely to successfully fill medication prescriptions that are e-prescribed compared to traditional, paper-based prescriptions. Given the chaotic nature of the ED with unplanned and irregularly-timed ED visit, we hypothesized that paper prescriptions would be filled more often than an e-prescriptions. To our knowledge, no study has examined the difference in fill-rates between electronic and paper prescriptions for ED patients.

We performed a retrospective chart review of discharged patients from the (blinded for peer review) ED between July 2016 and December 2016. (Blinded for peer review) is an urban academic, tertiary care hospital. We obtained institutional IRB approval prior to study commencement.

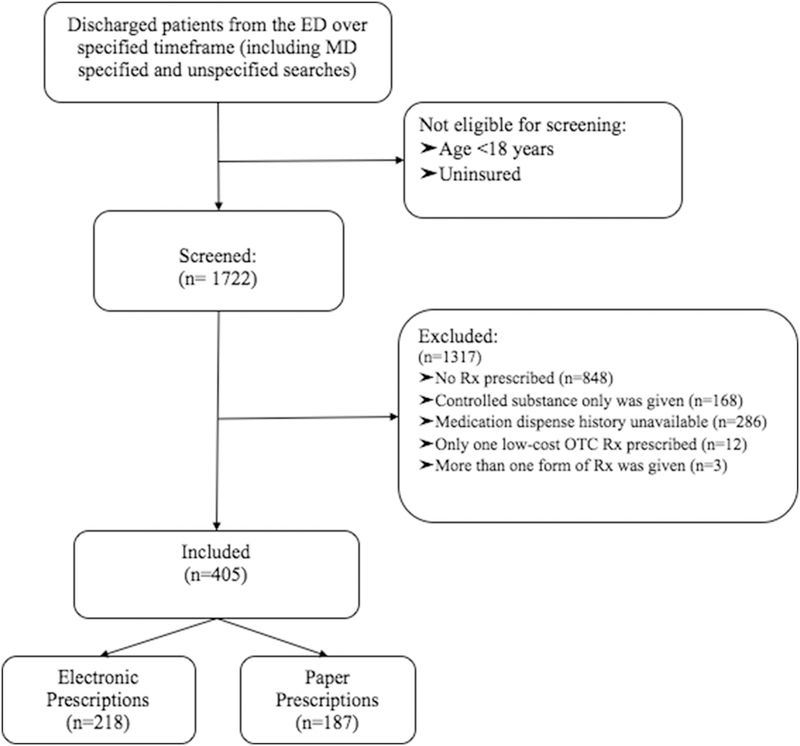

We sought to detect a minimum difference of 15% between the two study groups at 5% significance level and with a power of 80%. Assuming maximum uncertainty in an outcome (a baseline rate of 50%), we required a sample size for each group of 187 prescriptions. Our actual sample size was 405 in total with 187 paper prescriptions and 218 electronic prescriptions (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Study inclusion flowchart.

We screened insured adult patients discharged from our ED to identify those who received a non-controlled substance prescription. We used pharmacy claim-data (SureScripts) to determine fill rates. We included non-controlled substance prescriptions in either printed or electronic form. We excluded controlled prescriptions, as these could only be printed at the time of the study. We excluded uninsured patients as we could not track whether their prescriptions were filled by claims data.

The baseline characteristics of each study group were well matched and are presented in Table 1. The paper-prescription and e-prescribed groups had fill-rates of 58.3% and 57.8%, respectively. These rates were not significantly different (p=1). These results are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Overall patient characteristics*

| Characteristic: | Electronic Prescription (n=218) |

Paper Prescription (n=187) |

p-value** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 45.6 (17.5) | 40.4 (16.7) | .002 |

| Sex, # (%) | 1.0 | ||

| Female | 61 | 61.5 | |

| Male | 39 | 38.5 | |

| Insurance Type | .39 | ||

| Private | 18 | 26 | |

| Cal-Optima | 54 | 51 | |

| Medicare | 3 | 3 | |

| MediCal | 11 | 7 | |

| Dual coverage | 14 | 13 | |

| Number of Prescriptions | .027 | ||

| 1 | 67 | 53.5 | |

| 2 | 23 | 34 | |

| 3 | 6 | 9 | |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | |

| 5 or more | 0 | .5 | |

| Pharmacy Used | .50 | ||

| CVS | 37 | 39 | |

| Walgreens | 39 | 35 | |

| RiteAid | 4 | 8 | |

| Walmart | 6 | 5 | |

| Other | 14 | 12 | |

Table entries are in percentages (%) unless otherwise indicated

p-values were calculated using Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous variables and t-test for continuous variables

Table 2.

Comparison of prescription fill rates for electronic versus paper prescriptions

| Electronic prescription (n=218) |

Paper Prescription (n=187) |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fill rate, % (95% CI) | 57.8 (57.3–58.4) | 58.3 (57.8–59.0) | 1.0 |

Calculated using Fisher’s exact test

Our findings show that in the adult insured ED patient population, paper prescriptions were filled at the same rate as electronic prescriptions (58.3% versus 57.8%). This disproves our hypothesis that paper prescriptions would have a higher fill rate than electronic prescriptions. Several theories could explain this, first, perhaps the barriers to e-prescriptions are not as great as theorized, or perhaps they have advantages that are not yet realized. For example, the persistent automated reminders that pharmacies employ may make it difficult for patients to forget about their e-prescriptions. Finally, perhaps the disadvantages with paper prescriptions are greater than expected, such as being easily lost.

This study has several limitations, first, the data was collected from patients presenting to a single ED. In order to use pharmacy claim data via our EMR, we were limited to insured patients. Additionally, the study relied on the SureScripts medication dispense history. The rationale for choosing to use SureScripts’ pharmacy claim data was based on studies that have shown that using pharmacy claim data is more reliable than conducting phone interviews with patients [7–12]. However, the data may have been limited as SureScripts’ may not include name mismatches, over-the-counter medications, or prescriptions paid for directly by the patient. We limited this source of error by excluding low cost over the counter medications that would not typically be included in the fill history.

In summary, we found patients were equally likely to fill an electronic or paper prescription. This study contributes to the current literature as it presents the first direct-comparison of ED electronic versus paper prescription fill rates. Further research is needed to determine if these results are reproducible at multiple sites and if e-prescriptions are filled as often as paper prescriptions in uninsured populations, but this data may encourage emergency physicians to increase utilization of e-prescriptions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: UL1 TR001414/TR/NCATS NIH HHS/United States

Footnotes

COI disclosure: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper

REFERENCES

- [1].Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, Pub Law no. 111–5, 123 Stat 226–279. 123 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gabriel MH, Swain M. E-Prescribing Trends in the United States. ONC Data Br No 18 2014;2008(18):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Otterman S The End of Prescriptions as We Know Them in New York The New York Times; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Heller M, Patel N, Rose J. Mandatory E-Prescribing Is a Dangerous Rx for ED Patients. ACEPNow 2016;35(9):15. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Official New York state prescription forms, McKinney’s Pubic Health Law no. 281 2016. p. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wormser GP, Erb M, Horowitz HW. Are Mandatory Electronic Prescriptions in the Best Interest of Patients? Am J Med 2016;129(3):233–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ding R, Zeger SL, Steinwachs DM, et al. The validity of self-reported primary adherence among Medicaid patients discharged from the emergency department with a prescription medication. Ann Emerg Med 2013;62(3):225–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hohl CM, Abu-Laban RB, Brubacher JR, et al. Adherence to emergency department discharge prescriptions. Can J Emerg Med 2009;11(2):131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ginde AA, Von Harz BC, Turnbow D, Lewis LM. The effect of ED prescription dispensing on patient compliance. Am J Emerg Med 2003;21(4):313–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Freeman CP, Guly HR. Do accident and emergency patients collect their prescribed medication? Arch Emerg Med 1985;2(1):41–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Saunders CE. Patient compliance in filling prescriptions after discharge from the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 1987;5(4):283–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tackitt RD. The effects of an outpatient pharmacy on the acquisition of prescription medications by emergency room patients [Internet] University of Arizona; 1973. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10150/347835 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]