Abstract

Key message

Molecular and functional characterization of four gene families of the Physalis exon junction complex (EJC) core improved our understanding of the evolution and function of EJC core genes in plants.

Abstract

The exon junction complex (EJC) plays significant roles in posttranscriptional regulation of genes in eukaryotes. However, its developmental roles in plants are poorly known. We characterized four EJC core genes from Physalis floridana that were named PFMAGO, PFY14, PFeIF4AIII and PFBTZ. They shared a similar phylogenetic topology and were expressed in all examined organs. PFMAGO, PFY14 and PFeIF4AIII were localized in both the nucleus and cytoplasm while PFBTZ was mainly localized in the cytoplasm. No protein homodimerization was observed, but they could form heterodimers excluding the PFY14-PFBTZ heterodimerization. Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of PFMAGO or PFY14 aborted pollen development and resulted in low plant survival due to a leaf-blight-like phenotype in the shoot apex. Carpel functionality was also impaired in the PFY14 knockdowns, whereas pollen maturation was uniquely affected in PFBTZ-VIGS plants. Once PFeIF4AIII was strongly downregulated, plant survival was reduced via a decomposing root collar after flowering and Chinese lantern morphology was distorted. The expression of Physalis orthologous genes in the DYT1-TDF1-AMS-bHLH91 regulatory cascade that is associated with pollen maturation was significantly downregulated in PFMAGO-, PFY14- and PFBTZ-VIGS flowers. Intron-retention in the transcripts of P. floridana dysfunctional tapetum1 (PFDYT1) occurred in these mutated flowers. Additionally, the expression level of WRKY genes in defense-related pathways in the shoot apex of PFMAGO- or PFY14-VIGS plants and in the root collar of PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants was significantly downregulated. Taken together, the Physalis EJC core genes play multiple roles including a conserved role in male fertility and newly discovered roles in Chinese lantern development, carpel functionality and defense-related processes. These data increase our understanding of the evolution and functions of EJC core genes in plants.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11103-018-0795-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pre-mRNA splicing, Defense-related process, Exon junction complex (EJC), Functional evolution, Pollen maturation, Physalis floridana

Introduction

The exon junction complex (EJC) is a vital surveillance system in posttranscriptional regulation of mRNAs in eukaryotes, including pre-mRNA splicing, matured mRNA transport, non-sense mediated mRNA decay (NMD) and protein translation enhancement (Tang et al. 2004; Moore 2005; Ashton-Beaucage et al. 2010; Roignant and Treisman 2010; Ghosh et al. 2012; Kervestin and Jacobson 2012; Chazal et al. 2013; Le Hir et al. 2016). EJC is a multiple protein complex including both core and peripheral factors, which tightly bind to mRNAs in a splicing-dependent manner, and this protein complex establishes a molecular link between splicing and cytoplasmic processes (Le Hir et al. 2016). The EJC core consists of four proteins, including MAGOH NASHI (MAGO), RNA-binding motif 8A (RBM8A, also known as Y14), eukaryotic initiation factor 4A3 (eIF4AIII or eIF4A3) and metastatic lymph node 51 (MLN51/CASC3) in mammals or Barentsz (BTZ) in Drosophila (Ballut et al. 2005; Tange et al. 2005). These four proteins form intertwined interaction networks by stably clamping mRNA molecules in a sequence-independent manner during the posttranscriptional regulation process (Andersen et al. 2006; Bono et al. 2006). They provide a basic platform for peripheral factors to combine once the nuclear splicing machinery is formed (Le Hir et al. 2016).

Knowledge of EJC core proteins comes mainly from animal studies performed during the last 20 years. Both MAGO and Y14 are evolutionarily conserved proteins (Hachet and Ephrussi 2001; Mohr et al. 2001). Crystal structures of MAGO-Y14 heterodimer in Drosophila and humans show that the two proteins mainly associate with spliced mRNA (Lau et al. 2003; Shi and Xu 2003). MAGO is one of the strict maternal effect genes that plays a significant role in germ cell formation by regulating oskar mRNA localization in Drosophila (Boswell et al. 1991; Newmark and Boswell 1994; Micklem et al. 1997; Newmark et al. 1997). This protein also plays important roles in other developmental processes. It participates in hermaphrodite germ-line sex determination in Caenorhabditis elegans (Li et al. 2000) and controls cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdks) activity and proliferation and expansion of neural crest-derived melanocytes in mice (Inaki et al. 2011; Silver et al. 2013). It is also involved in the hedgehog signaling pathway in Drosophila (Garcia–Garcia et al. 2017). Y14/RBM8A, as the obligate interacting partner of the MAGO protein, exercises similar functions in oskar mRNA localization or sex-determination (Mohr et al. 2001; Fribourg et al. 2003; Kawano et al. 2004; Parma et al. 2007; Lewandowski et al. 2010). It targets neuronal genes to regulate anxiety behaviors in mice (Alachkar et al. 2013). Y14 provides a regulatory link between pre-mRNA splicing and snRNP biogenesis by modulating methylosome activity (Chuang et al. 2011). It inhibits the mRNA-decapping activity by interacting with decapping factors (Chuang et al. 2013, 2016) and modulates DNA damage sensitivity in an EJC-independent manner (Lu et al. 2017). The eIF4AIII belongs to the DEAD-box RNA helicase family and contributes almost entirely to the interface with RNA by forming an ATPdependent RNA clamp with its two conserved domains (Chan et al. 2004; Andersen et al. 2006; Bono et al. 2006; Gehring et al. 2009). The eIF4AIII interacts not only with the MAGO-Y14 heterodimer but also with BTZ, providing a molecular link among EJC core components (Palacios et al. 2004). Similar to MAGO and Y14 proteins, eIF4AIII is also required for oskar mRNA localization to the posterior end of mammalian oocytes (Palacios et al. 2004). Transcriptomewide CLIPseq (crosslinking-immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing) in Hela cells revealed that the purine-rich sequences motif GAAGA is the potential binding site of eIF4AIII (Saulière et al. 2012). Furthermore, eIF4AIII was found to be a specific translation initiation factor for CBC (cap-binding complex)-dependent translation (Choe et al. 2014). MLN51, the ortholog of BTZ, is a breast cancer protein and overexpressed in breast carcinomas (Tomasetto et al. 1995), and BTZ in Drosophila is also vitally responsible for oskar mRNA localization (van Eeden et al. 2001). However, many animal BTZ orthologs are mainly involved in promoting protein translation (Degot et al. 2004; Ha et al. 2008; Chazal et al. 2013). All the pre-EJC components can bind the nascent transcripts of intron-containing or intronless genes in Drosophila (Choudhury et al. 2016), and these four core proteins are assembled as a complex, exerting certain posttranscriptional roles as a function, for example, to affect gene splicing. This assumption is further supported by observations that the mutation or knockdown of each gene in D. melanogaster results in the skipping of several exons of mapk pre-mRNA (Ashton-Beaucage et al. 2010; Roignant and Treisman 2010). Knockdown of either EJC core component genes causes widespread and similar alternative splicing changes in mammalian cells (Wang et al. 2014).

Compared to animals, orthologs of the EJC core in plants have been largely overlooked since the first plant MAGO gene was isolated in rice (Swidzinski et al. 2001). To begin with, limited evidence suggests several essential roles of EJC genes in plants. MAGO, Y14 and eIF4AIII genes are involved in the growth, development and reproduction processes in some plant species (Park et al. 2009; Boothby and Wolniak 2011; Gong and He 2014; Gong et al. 2014a; Ihsan et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2016). MAGO and Y14 are regulated by ethylene and jasmonate and MAGO may be involved in the aggregation of rubber particles in Hevea brasiliensis (Yang et al. 2016). Arabidopsis eIF4AIII is co-localized with AtMAGO and AtY14 proteins, and its subcellular localization mode is altered in response to hypoxia or by different phosphorylation states (Koroleva et al. 2009; Cui et al. 2016). In rice, MAGO, Y14 and eIF4AIII are involved in the splicing of UNDEVELOPED TAPETUM1 (OsUDT1) transcripts (Gong and He 2014; Huang et al. 2016), a key transcription factor in anther and pollen development (Jung et al. 2005). There are no reports on the plant BTZ gene as yet. Moreover, the molecular and functional evolution of plant EJC genes is poorly known, although the MAGO and Y14 family have undergone slow coevolution to maintain their obligate heterodimerization (Gong et al. 2014b), and functional evolution of the duplicated MAGO-Y14, especially in Oryza, is associated with adaptive evolution (Gong and He 2014). Therefore, EJC core genes in plants require further study to understand the functional evolution of gene expression components in eukaryotes.

The fruit of Physalis spp. (Solanaceae) has a lantern structure. It is produced via heterotopic expression of MADS-box gene 2 in Physalis floridana (MPF2), and this gene is also associated with pollen development (He and Saedler 2005). MPF2 interacts with P. floridana MAGO (PFMAGO) proteins, and this finding helps to explain the role of MPF2 in male fertility (He et al. 2007), thus providing a new insight into the understanding of the origin of the Chinese lantern. To understand the developmental roles of plant EJC core genes, as well as potential roles in the development of the Chinese lantern, in this study, P. floridana EJC core genes (PFMAGO, PFY14, PFeIF4AIII and PFBTZ) were characterized in multiple ways, including phylogeny, gene expression, subcellular localization, protein–protein interaction (PPI) and developmental roles. We found that these genes shared similar evolutionary patterns and expression modes, but they also had many differences. Gene-specific downregulation demonstrated that these genes could affect multiple developmental processes, including a conserved role in male fertility determination and new functions in female fertility, Chinese lantern development and defense-related pathways. In particular, severe downregulation of PFMAGO, PFY14 and PFeIF4AIII produced lethal phenotypes. Accordingly, the transcripts of some genes in the related pathways were found to be modified either at expression levels or transcript forms, indicating the conserved roles of EJC core in mRNA metabolism, such as stability and splicing of transcripts.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Physalis floridana P106 (He and Saedler 2005) was grown in a greenhouse at the State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China) under long days (16 h light and 8 h dark) at a constant temperature of 23 °C. Nicotiana benthamiana plants were grown in an incubator (RXZ-380C; Ningbo) under long days (16 h light and 8 h dark) at a temperature of 25 °C and 22 °C.

RNA extraction

Roots and leaves were obtained from 3-month-old seedlings for organ-specific gene expression assays. Other organs/tissues were harvested as indicated, and immediately frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted using the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega, USA).

Sequence isolation

About 2.0 µg RNA from floral buds was treated with a RNase-free DNase I Kit (Promega, USA) in a 10 µl volume to remove genomic DNA contamination. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized with the oligo (dT)18 primers using M-MLV cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, China) following product instructions in a 20 µl volume. Full-length cDNA sequences of the involved genes were obtained by a routine RT-PCR method using gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S1). Each amplified fragment was purified using the High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Roche, Switzerland). Purified fragments were ligated into the pEASY®-Blunt Cloning vector (TransGen Biotech, China) and transformed into Trans10 chemically competent cells (TransGen Biotech, China). Sequencing was performed by Taihe Biotech, China.

Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) and phylogenetic analysis

MSA of the involved gene families was performed by BioEdit software version 5.09 (Hall 1999). Neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA 6.0 software (Tamura et al. 2013) with parameters of maximum composite likelihood model, pairwise deletion and bootstrap values for 1000 replicates.

Gene expression analyses

The first strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNAs of the indicated biological samples. For semi-quantitative RT-PCR, a 1.0 µl aliquot of the synthesized cDNA stock solution was used. Electrophoresis of PCR products was run on 1.0% agarose gels, photographed using an ultraviolet imager, and the typical results were presented. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) assay was carried out on an Mx3000p Real-time RT-PCR instrument (Stratagene, Germany) using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (TAKARA, Japan) at an amplification procedure consisting of 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 46 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 56 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 20 s, which were followed by a dissociation curve analysis. The PFACTIN gene was used as the internal reference in the RT-PCR analyses.

Yeast two-hybrid assays

ORFs of PFMAGO1, PFMAGO2, PFY14, PFeIF4AIII, and PFBTZ were respectively inserted into the pGADT7 or pGBKT7 vectors to form the prey or bait constructs, and then small yeast transformation mediated by LiAC was performed using manufacturer instructions (Clontech, USA). To confirm the protein interactions, nonlethal β-galactosidase activity analysis was performed on strict defective medium SD/-Leu-Trp-His-Ade as described previously (He et al. 2007).

Transient expression assays

For the subcellular localization, the ORF of PFMAGO1, PFMAGO2, PFY14, and PFeIF4AIII was inserted into the plant binary vector pCAMBIA1302 with restriction sites NcoI/SpeI, and fused to the N-terminal of GFP to form fusion proteins. PFBTZ coding sequence was inserted into another binary vector pSuper1300 with Xba I/ Kpn I to form the PFBTZ-GFP fusion protein due to limitation of restriction sites. Each fusion protein vector was agroinfiltrated into epidermal cells of Nicotiana benthamiana. A construct that produced only GFP was used as the control.

For the bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay, ORFs of MPF2, PFMAGO1, PFMAGO2, PFY14, PFeIF4AIII and PFBTZ were cloned into the pSPYNE-35S or pSPYCE-35S plant binary vector pair using Xba I/Kpn I to form either the N- or C-terminal ends of YPF protein. Combination of the N- and C-terminal resultant vectors was cotransformed into leaf epidermal cells of Nicotiana benthamiana by agroinfiltration (Walter et al. 2004). Fluorescence signals of GFP or YFP were observed by a confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus FV1000 MPE, Japan).

VIGS analysis

VIGS procedures were performed as previously described (Zhang et al. 2014). The trigger sequence for each gene silencing (Supplementary Fig. S1) was cloned into the TRV2. Leaves in 14DAI were used to identify gene silencing P. floridana lines by qRT-PCR. The gene expression in flowers, shoot apex, or root collar of each gene-specific VIGS plant was investigated using primers in Supplementary Table S1. The expression of target genes from 16 to 80 flowers or at least three independent samples of shoot apex or root collar was checked to evaluate the extent of gene silencing.

Morphological assays

Plant morphology was photographed using a digital single lens reflex camera (D7000, Nikon, Japan). The leaf primordium, root collar, flower, Chinese lantern, fruits and pollen grains were photographed using a Zeiss microscope (Zeiss, Germany). Pollen grain maturation was investigated using iodine–potassium iodide (I2–KI) staining.

Statistical analyses

Each experiment/measurement was performed using at least three independent biological replicates unless stated otherwise. Mean and standard deviation were presented. A Student’s two-tailed t-test was used for statistical analysis, which was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0 (IBM Corp, New York, USA).

Results

Isolation and sequencing analyses of P. floridana EJC core cDNAs

MAGO homologous genes were previously isolated in P. floridana and named PFMAGO1 (EF205415) and PFMAGO2 (EF205416). These two paralogs shared high sequence identity (He et al. 2007). In this study, we rescreened a P. floridana transcriptome using these two PFMAGOs as the template and no additional homologs were found. This suggests that only two MAGO-like genes exist in the P. floridana genome. For the other three EJC core genes, we used the Oryza sativa RBM8A/Y14 (KF051016/KF051017), Arabidopsis thaliana AteIF4AIII (NM_104029) and Homo sapiens MLN51/CASC3 (XM_005257163) to blast the P. floridana transcriptome. Only one copy of each gene was hit and these, respectively, were named PFY14, PFeIF4AIII and PFBTZ (Supplementary Table S2). The full-length cDNA of these genes was then isolated using RT-PCR, revealing that the open reading frame (ORF) of PFY14, PFeIF4AIII and PFBTZ encoded 188-, 391-, and 688-amino acid (aa) peptides, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). The predicted average hydropathicity values of the four EJC core homologous proteins were all negative (Supplementary Table S2), indicating that they were hydrophilic with a potential capability of shuttling between the nucleus and the cytoplasm.

Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of each protein family from 17 species was displayed including four animals and 13 plants (Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Fig. S2–S5). MAGO proteins were highly conserved (from 9 to 151 aa), while they did not contain any defined motifs. However, four conserved leucine residues that constituted a potential leucine zipper in the C-terminus were found (Pozzoli et al. 2004; Chu et al. 2009; Supplementary Fig. S2). Y14 proteins had a central RNA recognition motif (RRM, amino acids 77–170) flanked by highly divergent N- and C-terminal regions, and the most conserved regions in the RRM were RNP1 and RNP2 motifs (Lau et al. 2003; Shi and Xu 2003; Chu et al. 2009; Supplementary Fig. S3). The eIF4AIII protein belonged to DEAD-box helicase family which was characterized by the conserved motif Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp (DEAD). MSA showed that this protein family contained two RecA-like domains joined by an 11-residue linker (LVKRDELTLEG) and they possessed nine highly conserved motifs along with an N-terminal flanking sequence (Andersen et al. 2006; Cordin et al. 2006; Huang et al. 2016; Supplementary Fig. S4). The eIF4AIII in dicots had a conserved DESD motif instead of the DEAD motif occurring in animals, algae and monocots (Supplementary Fig. S4). The conserved region of the BTZ family was about 80-aa long and named SELOR or the eIF4AIII binding domain (Degot et al. 2004; Supplementary Fig. S5).

The conserved region size of each protein was summarized and their tertiary structures were predicted (Supplementary Fig. S6). PFBTZ was not predicted to have any secondary structure elements, whereas the other three EJC core proteins were composed of a variable number of α-helices and β-strands (Supplementary Fig. S6a). In the simulated Physalis EJC core tetrameric structure based on human EJC structure, the PFMAGO-PFY14 heterodimer kept the two domains of PFeIF4AIII in a closed conformation and the conserved SELOR domain of PFBTZ was wrapped around two domains of PFeIF4AIII (Supplementary Fig. S6b). This is similar to the structure of mammalian EJC, suggesting conserved roles of mRNA metabolism in the Physalis EJC core.

Evolutionary analysis of the EJC core protein families

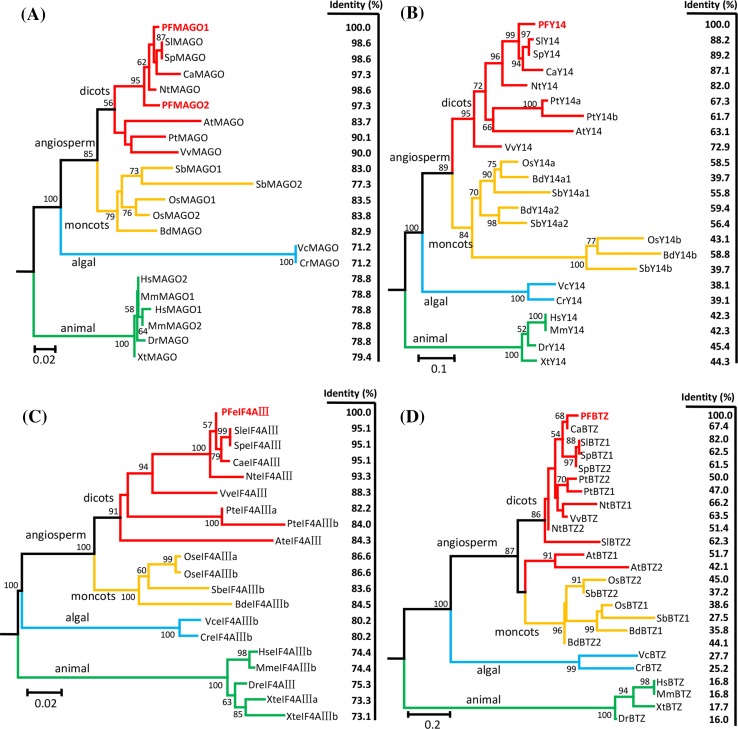

To reveal the evolutionary relationships of Physalis EJC core genes, sequence identity and phylogenetic analyses were performed based on the MSAs of these four protein families (Supplementary Fig. S2–S5). The sequence identity of each Physalis gene with other homologs was reduced within its own gene family, which was dependent on the evolutionary distance (Fig. 1). MAGO and eF4AIII families were relatively conserved since their sequence identity ranged from 73.1 to 98.6% (Fig. 1a, c), while the Y14 (38.1–89.2%) and BTZ (16.0–82.0%) families were highly divergent (Fig. 1b, d). The BTZ family was the most evolutionarily divergent of the four families (Fig. 1d). These observations indicate that the evolutionary speed of each gene family was different, but their divergence patterns were similar.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic reconstruction of EJC core genes. a Neighbor-Joining (NJ) tree of MAGO protein family. b NJ tree of the Y14 protein family. c NJ tree of the eIF4AIII protein family. d NJ tree of the BTZ protein family. The sequence identity compared with Physalis orthologs was indicated on the right panel of each tree. The amino acid sequences include the orthologs from Physalis floridana (PF), Solanum lycopersicon (Sl), Solanum pennellii (Sp), Capsicum annuum (Ca), Nicotiana tomentosiformis (Nt), Vitis vinifera (Vv), Populus trichocarpa (Pt), Arabidopsis thaliana (At), Oryza sativa (Os), Sorghum bicolor (Sb), Brachypodium distachyon (Bd), Volvox carteri nagariensis (Vc), Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Cr), Homo sapiens (Hs), Mus musculus (Mm), Danio rerio (Dr), and Xenopus tropicalis (Xt). Information on these genes is presented in Supplementary Table S3

Phylogenetic reconstruction using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method showed that the members of MAGO protein family from animal, algal and angiosperm lineages were clustered into three respective groups along the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1a). In the angiosperm lineage, the MAGO members of monocots and dicots were divided into two subgroups. PFMAGO1 and PFMAGO2 were clustered into one group with homologous members from solanaceous species, while PFMAGO1 was relatively close to solanaceous MAGO proteins (Fig. 1a). The MAGO members from the two species of algae were clustered and located at the base of the angiosperm-lineage, but with longer branch lengths (Fig. 1a). Similar topological structures were found in each phylogeny of Y14, eIF4AIII and BTZ protein families (Fig. 1b–d), indicating that they might have undergone similar evolutionary histories.

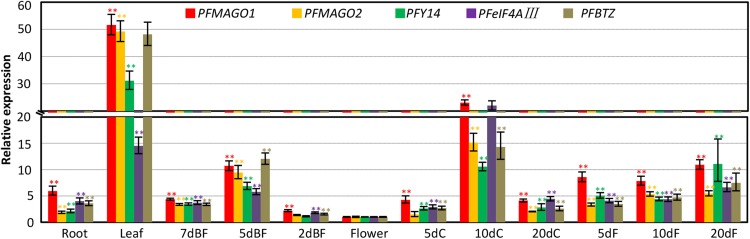

The expression of EJC core genes in Physalis

To obtain functional clues, gene expressions of Physalis EJC core genes were investigated. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was first performed with total RNA from roots, leaves, floral buds, flowers, fruiting calyx, and berries of P. floridana. The results indicated that five genes (PFMAGO1, PFMAGO2, PFY14, PFeIF4AIII and PFBTZ) were all transcribed, but at different levels, in the organs investigated (Supplementary Fig. S7). To quantify gene expression levels in each organ, qRT-PCR assays were performed. Gene expression data showed that each of the five genes had variable expression levels in different organs, and all five genes were also divergent within the same organs. Nonetheless, these genes shared an overall similar expression pattern (Fig. 2). The lowest expression of all genes was found in mature flowers. The expression of all genes was significantly higher in other detected organs and, in particular, they were highly expressed in leaves and 10 d old fruiting calyces (Fig. 2). Moreover, the expression of each gene was elevated in developing berries (Fig. 2). The extensive expression in all organs and the coincident expression profiles of these genes hinted that the EJC core component may cooperatively play multiple roles in growth, development and reproduction in P. floridana.

Fig. 2.

Expression patterns of EJC core genes in P. floridana. The total RNAs from roots, leaves, flower buds (7dBF, 5dBF, and 2dBF abbreviated for the flower buds of 7-, 5-, and 2-day before flowering), blooming flowers, fruiting calyx (5dC, 10dC and 20dC is short of the calyx of 5-, 10- and 20-day after fertilization) and developing berries (5dF, 10dF and 20dF represent fruits of 5-, 10- and 20-day after fertilization) were subjected to qRT-PCR. PFACTIN was used as an internal control. Experiments were performed using three independent biological samples. Mean and standard deviation are presented. The significance of gene expression differences in the detected organs relative to flowers was evaluated by a two-tailed t-test. Double asterisks in the same color for the same gene indicates significance at P < 0.01

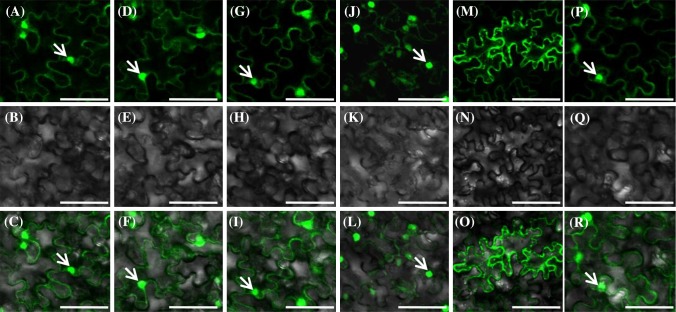

Subcellular localization of Physalis EJC core proteins

The EJC core proteins in animals are nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins (Le Hir et al. 2016). To study subcellular localization patterns of Physalis EJC core components, the ORF of each gene was fused in frame with GFP and was transiently expressed in tobacco leaf cells. The distribution of the GFP expression signal of the resultant construct in leaf cells indicated the subcellular localization of the EJC proteins. Using this technique, we found that PFMAGO1 (Fig. 3a–c), PFMAGO2 (Fig. 3d–f), PFY14 (Fig. 3g–i), and PFeIF4AIII (Fig. 3j–l) shared a similar distribution in that they might be localized both in the nucleus and cytoplasm. However, PFBTZ showed a distinct localization pattern. It was exclusively localized in cytoplasm, particularly in some small bodies (Fig. 3m–o). The GFP protein, as a control, was localized both in the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Fig. 3p–r). These results indicate that the Physalis EJC core may function in the nucleus and cytoplasm or have nucleocytoplasmic shuttling potential.

Fig. 3.

Subcellular localization of Physalis EJC core proteins in plant cells. a–c PFMAGO1-GFP. d–f PFMAGO2-GFP. g–i PFY14-GFP. j–l PFeIF4AIII-GFP. m–o PFBTZ-GFP. p–r GFP protein as the control. Bars, 50 µm. The first row shows signals in fluorescence fields; the second row shows signals in bright fields; the third row shows merged signals of fluorescence and bright fields. The arrow indicates the nucleus

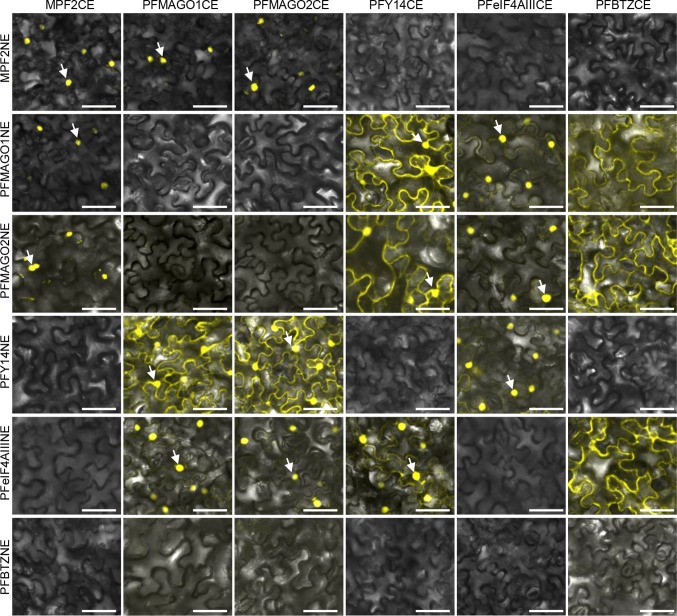

PPIs among Physalis EJC core components

Animal EJC core components form a tetramer to perform biological functions (Le Hir et al. 2016). Therefore, we studied the PPI capability among the Physalis EJC core components. A yeast two-hybrid assay was initially used (see “Materials and methods” section). MPF2 interacts with PFMAGO1 and PFMAGO2 (He et al. 2007) and thus these PPIs were included as the positive controls. An empty prey or a bait vector was included as a negative control. No interaction was observed between the Physalis proteins with the empty vector controls since there was no cell growth and no β-galactosidase activity (blue coloration). However, several PPIs among the Physalis EJC proteins were detected based on cell growth and appearance of the blue coloration (Fig. S8). Consistent with previous work (He et al. 2007), MPF2 formed homodimers and it also interacted with PFMAGO1 and PFMAGO2 (Fig. S8). However, MPF2 did not interact with the other Physalis EJC cores. Among the EJC, the PFY14 interacted with PFMAGO1 or PFMAGO2 protein (Fig. S8). PFBTZ might form homodimers since the yeast cells could grow normally, albeit with extremely low β-galactosidase activity. PFBTZ heterodimerized with PFMAGO1 or PFMAGO2 when PFBTZ acted as a prey protein. Interestingly, PFeIF4AIII did not interact with any of these EJC core components in yeast (Fig. S8).

The PPIs among Physalis EJC core proteins were also investigated in plant cells by bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analyses. The ORF of each EJC core protein was cloned into a pSPYNE-35S or pSPYCE-35S vector that coded half of the yellow fluorescence protein (YFP) to generate EJC-YFPn or EJC-YFPc fusion proteins, respectively. The detection of the YFP signal in plant cells that were co-transformed with any combination of YFPn- and YFPc-derived fusion constructs indicated that the two proteins could interact. Otherwise, no PPI was detected. In BiFC assays, the positive control, MPF2 not only formed homodimers but also interacted with each of the MAGO (PFMAGO1 and PFMAGO2) proteins, and the YFP signals clearly originated in the nucleus (Fig. 4). Moreover, MPF2 did not interact with other EJC cores in plant cells (Fig. 4). Among the EJC core components, PFMAGO1 or PFMAGO2 interacted with PFY14 both in the nucleus and cytoplasm to form heterodimers. As such, the detected PPIs and non-PPIs patterns in plant cells (Fig. 4) were similar to the Y2H assay (Supplementary Fig. S8). However, some differences were apparent. In plant cells, the PFeIF4AIII could interact with the other three EJC core components (PFMAGO1, PFMAGO2 and PFY14) to form different heterodimers, and strong YFP signals in the nucleus were observed (Fig. 4). In plant cells PFBTZ was unable to form the homodimer but additional heterodimerization with PFeIF4AIII in one orientation was detected and all the detected PPI (YFP) signals associated with PFBTZ were largely from the cytoplasm, i.e., when heterodimerizing with PFMAGO1, PFMAGO2, and PFeIF4AIII (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

PPIs of Physalis EJC core in plant cells. Tobacco epidermal cells were co-transformed with the constructs of both YFPn (vertical panels) and YFPc (horizontal panels) fusion proteins. The arrow indicates the nuclei. Bars, 50 µm

Developmental roles of EJC core components in Physalis

To study developmental roles of PFMAGO1, PFMAGO2, PFY14, PFeIF4AIII and PFBTZ in P. floridana, we used the virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) approach. A gene-specific coding fragment was used as the trigger sequence to create VIGS constructs (PFMAGO1-TRV2, PFY14-TRV2, PFeIF4AIII-TRV2, and PFBTZ-TRV2) (Supplementary Fig. S1). One hundred and twenty P. floridana seedlings (30 days old) were infected for each gene. A total of 30 seedlings were simultaneously infected using an empty TRV2 construct as the negative control (NC) and 30 seedlings were untreated as wild type (WT) controls (Supplementary Fig. S9a). It was difficult to make a gene-specific silencing construct due to high sequence identity (87.6%) of PFMAGO1 and PFMAGO2. Thus, the two genes were aimed to be simultaneously downregulated using part of PFMAGO1 as the trigger sequence, which shared 89.0% sequence identity with the corresponding section of PFMGO2 (Supplementary Fig. S1). The derivative VIGS plants were named PFMAGO-VIGS. The VIGS products of other genes were respectively named as PFY14-, PFeIF4AIII- and PFBTZ-VIGS plants. The expression of each EJC gene in Physalis leaves was detected in VIGS plants using qRT-PCR analyses at 14 days after infection (14DAI) and revealed 112–115 true downregulated VIGS plants for each gene (Supplementary Fig. S9a). These VIGS plants grew as normal as the WT and NC plants before the 14DAI stage (Supplementary Fig. S9b). However, more than half of PFY14- and PFMAGO-VIGS plants, respectively, began to display abnormal growth at the 21DAI and 28DAI stages, while the PFeIF4AIII- and PFBTZ-VIGS plants were apparently normal and similar to the WT and NC plants at these stages (Supplementary Fig. S9b). Further analyses of the results are described, below, per gene.

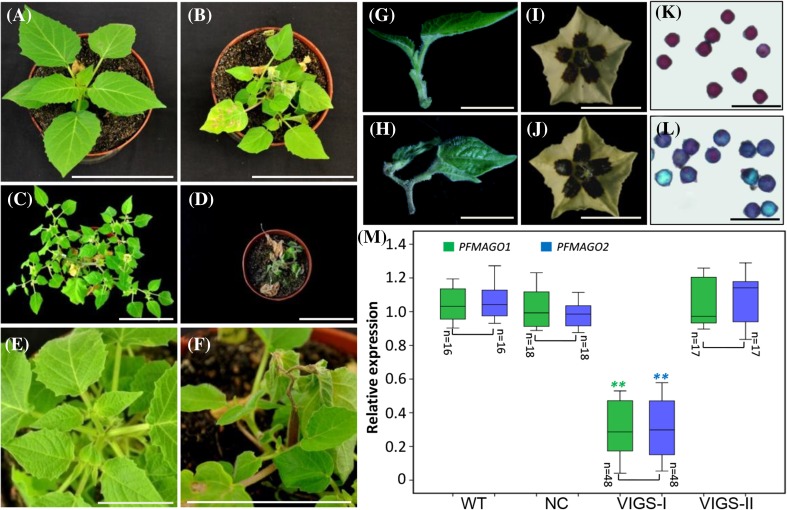

PFMAGO genes have roles in both vegetative and reproductive growth

PFMAGO-VIGS plants grew normally before 21DAI (Supplementary Fig. S9b) then leaves at the top of the main stem became warped and drooped compared to NC and WT (Fig. 5a, b). Three months later, NC and WT plants had luxuriant growth with many flowers and fruits (Fig. 5c), but about 75% of the PFMAGO-VIGS plants had withered and died after flowering (Fig. 5d). Shoot apex exsiccation and leaf withering might have been the main causes of plant death (Fig. 5e–h). Only 25 out of 115 (21.7%) VIGS plants survived (Supplementary Fig. S9a). These surviving plants attained the reproductive stage and developed a few flowers. Compared to WT and NC, flower morphology in PFMAGO-VIGS plants did not appear to be changed (Fig. 5i, j). However, only rarely did flowers produce fruits and the fruit setting rate was 35.3% (Supplementary Fig. S9a). If cross-pollinated with WT pollen, the fruit setting reached 90% (Supplementary Fig. S9a), indicating that the female organ was functional. However, I2–KI staining assays revealed that pollen viability or maturation of most PFMAGO-VIGS flowers was greatly reduced compared to NC (Fig. 5k, l and Supplementary Fig. S9a). qRT-PCR analyses showed that the expression of both PFMAGO genes was significantly knocked down in these PFMAGO-VIGS flowers (P < 0.01, defined as VIGS-I). In the PFMAGO-VIGS flowers that showed WT-like pollen development (defined as VIGS-II), the PFMAGO expression was not altered compared to the WT and NC plants (Fig. 5m). These results indicated that PFMAGO genes in P. floridana primarily affect shoot apex development and male fertility.

Fig. 5.

Phenotypic analysis of PFMAGO-VIGS in P. floridana. a, b NC and PFMAGO-VIGS plants in 28DAI stage. c, d NC and PFMAGO-VIGS plants in the fruiting stage. e, f Phenotype of shoot apex growth at 28DAI stage in NC and PFMAGO-VIGS plants. g, h Shoot apex of NC and PFMAGO-VIGS plants. i, j NC and PFMAGO-VIGS flowers. k, l Pollen viability in NC and PFMAGO-VIGS flowers, which was evaluated by I2–KI staining. m The expression of both PFMAGO1 and PFMAGO2. Total RNAs from different flowers and number (n) as indicated were subjected to qRT-PCR. WT wild type, NC negative control, VIGS-I, PFMAGO-VIGS flowers showing pollen abortion; VIGS-II, PFMAGO-VIGS flowers showing WT-like pollen development. Bars, 10 cm in a–h, 1 cm in i and j, and 100 µm in k, l. Significance relative to NC was evaluated by a two-tailed student’s t test, and double asterisks indicates significance at P < 0.01

PFY14 is involved in shoot apex development and fertility processes

PFY14-VIGS plants grew normally before the 14DAI stage but they began to differ from WT and NC plants at the 21DAI stage (Supplementary Fig. S9b and Supplementary Fig. S10a, b). Some lines of PFY14-VIGS plants displayed early blossoming and displayed a severe leaf withered phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S10b). Three months later, all PFY14 effectively downregulated VIGS plants were dead (Supplementary Fig. S9a). During the vegetative growth stage, the shoot apex of WT and NC plants was deep green and viable (Supplementary Fig. S10c). In PFY14-VIGS plants the shoot apex was distorted and showed a leaf-blight-like phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S10d) with inhibition of new leaf or flower primordia morphogenesis. Fewer and smaller flowers relative to WT and NC were observed in some PFY14-VIGS plants (Supplementary Fig. S10b, e, f). Unfortunately, these flowers quickly withered and dropped after bloom. Pollen viability was investigated, compared to NC. Less than 36% of the pollen grains from the PFY14-VIGS flowers stained blue (Supplementary Figs. S9a, S10g, h), suggesting inhibition of pollen maturation. At the end of the experiment, no fruit was obtained from the PFY14-VIGS plants either naturally or by artificial pollination with WT pollen (Supplementary Fig. S9a). This indicated that the female function might also have been damaged. The PFY14 expression in all observed PFY14-VIGS flowers was seriously down-regulated compared to WT and NC plants (P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. S10i). Therefore, PFY14 plays significant roles in shoot apex development, carpel functionality and male fertility processes in P. floridana.

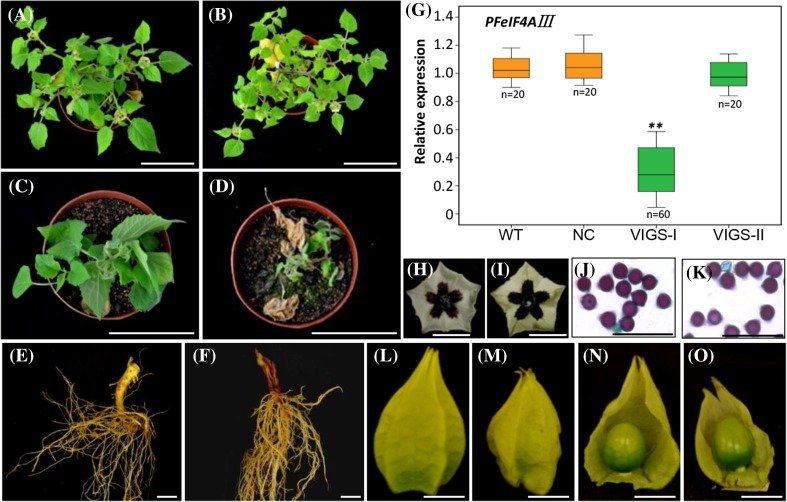

PFeIF4AIII roles in Chinese lantern development and root collar growth

Nearly 40% (44 out of 113) PFeIF4AIII-VIGS grew as strongly as NC plants at the flowering stage, and these plants blossomed and bore fruit normally (Fig. 6a, b and Supplementary Fig. S9a). However, the other 69 PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants died after flowering (Fig. 6c, d). We found that the root collar area was rotten in these dead PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants compared to the NC plants (Fig. 6e, f). qRT-PCR results indicated that PFeIF4AIII expression in the root collar of these PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants was severely downregulated (P < 0.01, defined as VIGS-I), while, in the PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants that showed normal phenotypes (defined as VIGS-II), the gene expression was not altered compared to the WT and NC plants (Fig. 6g). Flower morphologies and pollen grain activities of the surviving PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants showing severe PFeIF4AIII downregulation was similar to NC plants (Fig. 6h–k), and these plants could set fruit naturally or via artificial pollination with WT pollen (Supplementary Fig. S9a). The Chinese lantern shape of PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants was irregular compared to NC (Fig. 6l, m) but the berries were normal (Fig. 6n–o). Therefore, PFeIF4AIII may be involved in Chinese lantern development and root collar growth in P. floridana.

Fig. 6.

PFeIF4AIII-VIGS analysis in P. floridana. a, b Growth of NC and PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants at the fruiting stage. c, d PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants displayed wilting and died after flowering compared to NC plants. e, f Root growth of NC and PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plant. g The PFeIF4AIII expression in root collar area of plants as indicated. WT, wild type; NC, negative control; VIGS-I, PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants showing root collar decay; VIGS-II, PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants having WT-like root collar. The investigated sample number (n) in each case was indicated. h, i Flower morphology in NC and PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants. j, k Pollen viability in NC and PFeIF4AIII-VIGS flowers, which was evaluated by I2–KI staining. l, m ICS morphology in NC and PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants. n, o Fruit morphology in NC and PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants. Bars, 10 cm in a-d, 2 cm in e, f, 1 cm in h, i and l–o, and 100 µm in j, k. Significance relative to NC was evaluated by a two-tailed student’s t test, and double asterisks indicates significance at P < 0.01

PFBTZ is mainly involved in male fertility

PFBTZ-VIGS plants differed from PFMAGO-, PFY14-, and PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants and they appeared as normal as WT or NC plants during the entire developmental process (Supplementary Fig. S9 and Supplementary Fig. S11a, b). All of the PFBTZ-VIGS plants survived and set fruits (Supplementary Fig. S9a). The morphology of the flowers and fruits of the PFBTZ-VIGS plants was similar to NC plants (Supplementary Fig. S11c–f). The fruit setting rate of the PFBTZ-VIGS plants under natural conditions was only 68% and this was significantly less than NC plants (Supplementary Fig. S9a). However, artificial pollination with WT pollen significantly increased the fruit setting rate to 92% (Supplementary Fig. S9a), suggesting that the female organ was not affected. I2–KI assays showed that pollen grain viability in PFBTZ-VIGS flowers was poor (~ 50%) compared to WT and NC flowers (Supplementary Figs. S9a, S11g, h). The PFBTZ expression in these mutated flowers was significantly downregulated (VIGS-I) compared to WT and NC (P < 0.01), while pollen viability of the PFBTZ-VIGS plants that showed the PFBTZ expression of VIGS-II grade was normal (Supplementary Fig. S11i). Thus, PFBTZ mainly participates in the functional determination of male fertility in P. floridana.

Gene expression variation in knockdowns of P. floridana EJC core genes

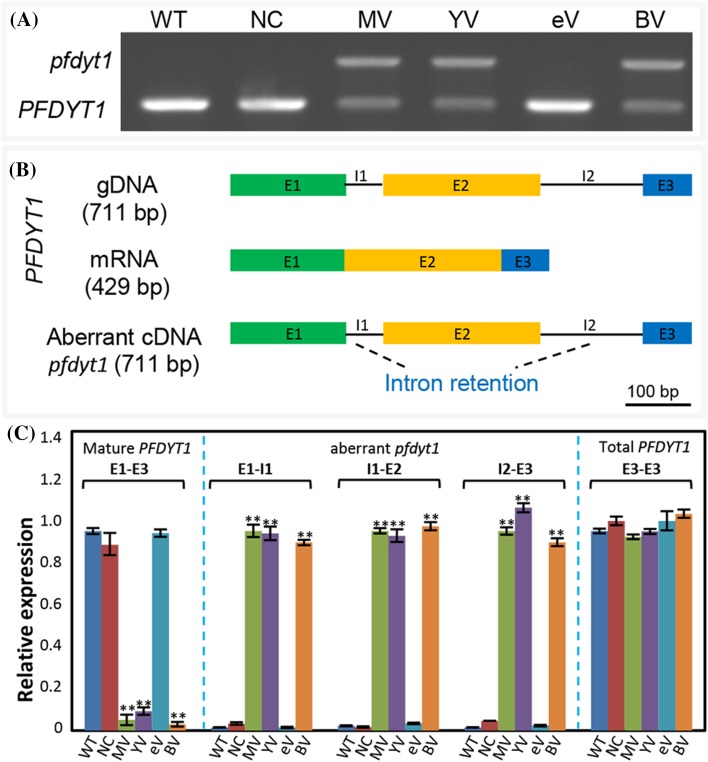

EJC controls the splicing of P. floridana dysfunctional tapetum1 (PFDYT1)

A common abnormality in PFMAGO-, PFY14-, and PFBTZ-VIGS plants was to produce premature pollen. We therefore detected the expression variation of the genes involved. The splicing of the OsUDT1 gene that is essential to pollen maturation in rice is regulated by the EJC core (Gong and He 2014; Huang et al. 2016). Two orthologs of the OsUDT1 gene, tomato male sterile 1035 (Ms1035) and Arabidopsis AtDYT1, also play essential roles in pollen development and meiosis in anthers (Jeong et al. 2014). Using Ms1035 (XM_004233756) as the template to screen the P. floridana transcriptome, only one unigene was found with high sequence identity (91.6%), and this was named P. floridana dysfunctional tapetum 1 (PFDYT1). The ORF of PFDYT1 was 429 base pairs. To investigate expression variation of the PFDYT1 gene, total RNAs of floral organs were extracted from the WT, NC, PFMAGO-, PFY14-, PFeIF4AIII- and PFBTZ-VIGS plants and subjected to conventional RT-PCR assays (Fig. 7a). RT-PCR, using gene-specific primers that flanked the full coding region, showed that the mature PFDYT1 transcripts were severely downregulated in PFMAGO-, PFY14- and PFBTZ-VIGS flowers, but a large transcript of about 700 bp was also detected compared to WT, NC and PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants (Fig. 7a). Cloning and sequencing showed that the large PFDYT1 transcript was 711 bp and was identical with its genomic sequence including three exons and two introns (Fig. 7b). This suggested that intron retention happened during PFDYT1 transcription once PFMAGO, PFY14 or PFBTZ was downregulated. The aberrant transcripts (pfdyt1) due to intron retention failed to encode full-length PFDYT1 proteins (Supplementary Fig. S12). To rigorously confirm the expression variation, qRT-PCR was conducted. The variation of PFDYT1 mature mRNA level, which significantly decreased (P < 0.01, Fig. 7c), was identical to the observation from routine RT-PCR (Fig. 7a). However, when a primer flanking occurred on the intron (i.e., E1–I1, I1–E2, or I2–E3), a contrasting variation was observed, and strong expression signal of the PFDYT1 transcripts occurred in PFMAGO-, PFY14-, and PFBTZ-VIGS floral organs instead of WT, NC and PFeIF4AIII-VIGS flowers (Fig. 7c), indicating an increase of aberrant pfdyt1 transcripts in PFMAGO-, PFY14-, PFBTZ-VIGS flowers, while the total mRNA level seemed not to be affected. We further investigated this using primers flanking exon3 (E3), which were presumed to amplify the total PFDYT1 mRNA level. It turned out that the total mRNA level of PFDYT1 gene was indeed comparable between the controls and the VIGS plants (Fig. 7c), suggesting that the unspliced forms of the PFDYT1 mRNA in these VIGS plants were stably accumulated. Therefore, PFMAGO, PFY14 and PFBTZ are involved in the control of the splicing of the PFDYT1 transcripts.

Fig. 7.

Accumulation of aberrant pfdyt1 transcripts in EJC core knockdowns. a Full-length transcripts of PFDYT1 in floral buds revealed by RT-PCR. WT, NC, MV, YV, eV and BV respectively represent wild type, negative control (TRV2), PFMAGO-, PFY14-, PFeIF4AIII- and PFBTZ-VIGS plants. The extension time was 30 s. A larger transcript designated pfdyt1 occurred in the indicated flowers. b The PFDYT1 splicing is altered in the knockdowns of the EJC core genes. The structure of gDNA, cDNA in WT plants, and aberrant transcript in the VIGS plants was demonstrated. Color rectangles, exons (E1–E3); black lines, introns (I1, I2). c Relative expression levels of mature PFDYT1, abnormal pfdyt1 (E1–I1, I1–E2, I2–E3) and total (E3–E3) mRNA as indicated. Total RNAs from floral buds (7DBF) of WT, NC and PFMAGO-, PFY14-, PfeIF4AIII- and PFBTZ-VIGS plants were subjected to qRT-PCR. PFACTIN mRNAs were used as internal control. The extension time was 10 s. In detection of mature PFDYT1 RNA (left), the expression in WT was set as 1, while in detection of aberrant pfdyt1 transcripts (right), the expression in floral buds of each MV was set as 1. Three independent biological samples were used, and error bars represent SD. Significance relative to WT was evaluated by a two-tailed student’s t test, and double asterisks indicates significance at P < 0.01

EJC alters gene expression levels of tapetal programmed cell death pathway

A well-studied pathway is the function of male fertility associated with the tapetal programmed cell death (PCD) pathway, forming DYT1-TDF1-AMS-bHLH91 transcriptional cascade in rice, Arabidopsis and tomato (Jeong et al. 2014). We investigated the expression of the downstream genes of PFDYT1 in P. floridana. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicon) tapetal PCD genes SlTDF1 (Soly03g113530), SlAMS (Soly08g062780), SlbHLH91 (Soly01g081100), SlCysteine protease (SlCysP, Soly07g053460) and SlAspartic protease (SlAspP, Soly06g069220) were used to blast the P. floridana transcriptome, revealing their putative orthologs named PFTDF1 (MH319843), PFAMS (MH319844), PFbHLH91 (MH319845), PFCysP (MH319846), and PFAspP (MH319847). Their mature transcripts were amplified using RT-PCR, and transcript form was not altered compared to WT and NC (Supplementary Fig. S13a). However, the expression of PFTDF1, PFAMS, PFbHLH91, and PFCysP was downregulated in PFMAGO-, PFY14 and PFBTZ-VIGS flowers (P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. S13a, b). Meanwhile, the expression of PFAspP in PFMAGO- and PFY14-VIGS flowers was downregulated but not affected in the PFBTZ-VIGS flowers (P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. S13a, b). Nevertheless, the expression of all investigated genes was not altered in PFeIF4AIII-VIGS flowers (Supplementary Fig. S13a, b). Thus, PFMAGO, PFY14 and PFBTZ may affect gene expression of microspore development pathways in P. floridana.

EJC affects expression level of WRKY genes associated with defense-related pathways

Plant death was observed in the knockdowns of some Physalis EJC core genes, and either withered leaves or rotten root collar phenotypes were seen in these plants. These responses might be an alteration in the resistance or defense to certain biotic stresses. To study this, we also detected the expression of relevant genes. The WRKY genes StWRKY8 and StWRKY1 in potato, PtWRKY70 in Populus, and their tomato orthologs SlWRKY31, SlWRKY75 and SlWRKY81 are involved in resistance to the plant leaf blight phenotype (Mandal et al. 2015; Yogendra et al. 2015, 2017). We therefore isolated the three Physalis WRKY genes named PFWRKY31 (MH319849), PFWRKY75 (MH319850), and PFWRKY81 (MH319851), and the expression of these WRKY genes in the VIGS tissues was investigated. No splicing alteration was observed but a decrease of the WRKY genes was detected (Supplementary Fig. S13c). Further qRT-PCR showed that PFWRKY75 and PFWRKY81 were severely downregulated in the shoot apex of PFMAGO- and PFY14-VIGS plants, and PFWRKY31 and PFWRKY81 were downregulated in the root collar of the PFeIF4AIII-VIGS (P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. S13d), where significant plant death was observed. However, significant downregulation of only one gene PFWRKY31 and unaltered expression of all three WRKY genes were respectively observed in the shoot apex of PFBTZ- and PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants (Supplementary Fig. S13d) where no withered leaves were observed. Therefore, EJC core genes may be involved in defense-related processes associated with WRKY genes.

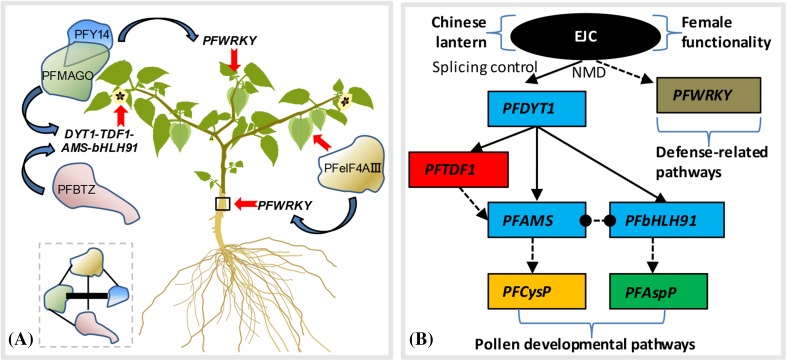

Discussion

Molecular evolution of EJC core genes is conserved, but their developmental roles seem to be diverse. The EJC core genes have been well studied in animals. However, studies of the protein core complex in plants have been less thorough. In this study, we compared the evolutionary conserved characteristics of P. floridana EJC core genes to other orthologs and found that they are involved in multiple developmental processes. Reduced fruit setting after downregulating EJC core genes appeared to be a consequence of poor fertility, particularly male fertility, since artificial fertilization with WT pollen largely rescued fruit setting. Therefore, EJC core genes are primarily involved in male fertility pathways and may participate in female functionality determination, Chinese lantern development or defense-related processes in P. floridana (Fig. 8a).

Fig. 8.

Multiple roles of EJC core homologs in Physalis. a Developmental roles of EJC core components in Physalis. Heterodimerization of EJC core proteins and subsequently recruiting peripheral proteins to form a functional higher order complex is essential for EJC core functions (Le Hir et al. 2016). Moreover, the MGAO-Y14 heterodimerization is obligate and functions as a functional unit (Gong et al. 2014a, b). As demonstrated in the dashed box, heterodimerization was usually formed among Physalis EJC core proteins (indicated by the line), but heterodimerization of PFY14 and PFBTZ was not observed. The obligate PFMGAO-PFY14 heterodimerization is highlighted using the thick line. Single Physalis EJC core protein or heterodimer PFMGAO-PFY14 is presented to stand for each-containing functional complex instead of itself. Blue arrows indicate activation of the downstream genes, and red arrows point to the organs or tissues where the EJC genes exert their developmental affects. Black box defines the root collar area. For the details, see text. b The proposed working model for EJC genes in Physalis. The putative tapetal PCD genes in Physalis were constructed according to Jeong et al. (2014). Blue boxes, basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor; red box, MYB transcription factor; yellow box, cysteine (Cys) protease gene; green box, aspartic (Asp) protease gene; gray box, WRKY transcription factor. The dot indicates PPI. Arrows represent positive regulation. The dashed lines represent predicted regulation or interaction

Functional conservation of plant EJC genes in male fertility

MAGO, Y14 and eIF4AIII genes have been studied in other plant species, and they are mainly involved in male fertility (He et al. 2007; van der Weele et al. 2007; Park et al. 2009; Boothby and Wolniak 2011; Gong and He 2014; Gong et al. 2014a; Ihsan et al. 2015; Cilano et al. 2016; Huang et al. 2016). However, no functional role for the BTZ gene has been found in plants. We found, using the VIGS approach, that PFMAGOs, PFY14 and PFBTZ are all involved in the pollen maturation process. This suggests a conserved role of the EJC core in male fertility. However, the mechanisms of these genes in male fertility are unknown. Serving as the first functional clue, PFMAGO1 and PFMAGO2 were observed to interact with MADS-domain protein MPF2, which plays a role in male fertility (He and Saedler 2005; He et al. 2007), suggesting that PFMAGO is involved with male fertility control by interacting with the essential regulators of pollen development. Further support for this assumption comes from Withania somnifera, where the WsMAGO2 gene is regulated through the anther-specific GAATTTGTGA motif, and the encoded protein interacts with MPF2-like proteins and affects male fertility by producing abortive pollen or seeds (Ihsan et al. 2015).

Rice studies have also provided clues to the role of EJC core genes in male fertility. RNAi of OsMAGO1-OsMAGO2 and OsY14a made various splicing products of OsUDT1 via intron retention and exon skipping in rice flowers. These resulted in degradation of the endothecium and tapetum leading to abnormal pollen grain development (Gong and He 2014). Identical alternative splicing evidence of OsUDT1 was also found in OsRH2 and OsRH34 (eIF4AIII orthologs) double knockdown transgenic rice plants (Huang et al. 2016). OsUDT1 is the ortholog of DYT1 encoding a bHLH transcription factor (Jung et al. 2005; Jeong et al. 2014), which is the essential upstream regulator of the well-studied tapetum PCD pathway including the DYT1 (bHLH)-TDF1 (MYB)-AMS (bHLH)-bHLH91 transcription cascade in rice, Arabidopsis and tomato (Jeong et al. 2014). DYT1 is involved in tapetum development (Zhang et al. 2006; Zhu et al. 2015). TDF1 plays a role in callose dissolution (Zhu et al. 2008). AMS (Sorensen et al. 2003) and bHLH91 (Xu et al. 2010) participate in PCD-triggered cell death. The downstream genes of the transcriptional cascade AspP (Niu et al. 2013) and CysP (Lee et al. 2004; Li et al. 2006) are respectively involved in PCD-triggered cell death and in anther cell wall modification and degradation. To understand the role of the Physalis EJC genes in controlling male fertility, we investigated the gene expression in the tapetum PCD pathway. We determined putative orthologs of these genes in P. floridana. For example, PFDYT1 is the ortholog of OsUDT1 in rice and SlDYT1 (Ms 1035) in tomato (Fig. 8b). We found that knockdown of PFMAGO, PFY14 and PFBTZ genes led to abnormal PFDYT1 pre-mRNA splicing accumulation via intron retention. Similar events were observed in the downregulation of rice EJC genes (OsMAGO-, OsY14-, or eIF4AIII), and abnormal transcript species resulted from first intron retention, partial or whole exon lacking (Gong and He 2014; Huang et al. 2016). These indicate the conserved splicing target of plant EJC genes in male fertility is DYT1 or UDT1.

The abnormal splicing of PFDYT1 might affect the expression of downstream genes such as PFTDF1, PFAMS and PFbHLH (Fig. 8b), and we observed that these genes in this tapetum PCD pathway were extremely downregulated. This suggests that the transcription cascade regulating pollen development is largely conserved. Pollen development was not changed in PFeIF4AIII-VIGS flowers, and the expression of PFDYT1 and the related downstream genes was not altered, indicating the target specificity of different EJC core genes. The aberrant transcript pfdyt1 could not encode a normal PFDYT1 protein, and the downregulation of these downstream genes is likely due to reduction of mature PFDYT1. Therefore, downregulating any of the three Physalis EJC core genes (PFMAGO, PFY14 and PFBTZ) disrupts the conserved EJC function in male fertility. This is correlated with the accumulation of abnormal pre-mRNA and expression alteration of a series of downstream genes in the tapetum PCD pathway, also implying that the NMD role might be impaired in the VIGS plants of these EJC core genes.

EJC genes are involved in defense-related processes in Physalis

NMD is a eukaryotic quality-control mechanism that governs the stability of both aberrant and normal transcripts. NMD inhibition during biotic stress contributes to the development of immunity responses (Shaul 2015). There is evidence that EJC is involved in defense-related pathways of plants. In rice, both OsMAGO2 and OsY14b genes show high sensitivity to a variety of abiotic stresses (Gong and He 2014). In Hevea brasiliensis, HbMAGO and HbY14 genes have different expression patterns in response to ethylene and jasmonate treatments (Yang et al. 2016). AteIF4AIII shares functions in abiotic stress adaptation in Arabidopsis. The orthologs of the stress-related helicases PDH45 and MH1 in Pisum sativum and Medicago sativa (Pascuan et al. 2016), and subcellular localization of Arabidopsis eIF4AIII was influenced by hypoxic environments (Koroleva et al. 2009). These observations suggest that the EJC core component may be involved in plant defense-related pathways. In our study, phenotypes resembling leaf-blight or showing root collar decay were observed in PFMAGO-, PFY14 and PFeIF4AIII-VIGS transgenic Physalis plants. We inferred that the regulation of defense against biotic stresses may be hindered due to knocking these EJC genes down.

The WRKY gene family in Arabidopsis is important in the defense-related pathways that guard against biotic stresses, such as bacterial and fungal pathogens (Ulker and Somssich 2004; Higashi et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2008; Mukhtar et al. 2008; Pandey et al. 2010). In Solanum lycopersicon, SlWRKY genes are also involved in response to multiple abiotic and biotic stresses including drought, salt stress and Pseudomonas syringae invasion (Huang et al. 2012). SlDRW1 (S. lycopersicon defense-related WRKY1, also named SlWRKY31) is involved in Botrytis cinerea resistance and tolerance to oxidative stress in tomato (Liu et al. 2014), while the StWRKY8 ortholog in Solanum tuberosum is involved in late blight resistance with the benzylisoquinoline alkaloid pathway (Yogendra et al. 2017). StWRKY1, the ortholog of SlWRKY75, confers late blight resistance by regulating phenylpropanoid metabolites in potato (Yogendra et al. 2015). PtWRKY70-RNAi in Populus alters salt stress and leaf blight disease responses (Zhao et al. 2017). We therefore studied the expression of three WRKY genes in Physalis, and found PFWRKY31, PFWRKY75 and PFWRKY81 were severely reduced in the shoot apex or root collar of PFMAGO-, PFY14- or PFeIF4AIII-VIGS plants. The growth of PFBTZ-VIGS plants appeared similar to wild plants, and the three WRKY expressions were not altered. Therefore, PFMAGO-, PFY14- and PFeIF4AIII might directly or indirectly regulate the expression of WRKY genes, via NMD for example, to affect plant defense pathways (Fig. 8b). The molecular details need further investigation, but this finding helps us to understand the adaptive role of EJC in plant evolution.

Generality and specificity of EJC roles and targets

EJC core components MAGO, Y14, eIF4AIII and BTZ form a stable polymer structure in animals (Andersen et al. 2006; Bono et al. 2006; Gehring et al. 2009; Le Hir et al. 2016). In eukaryotes, the MAGO and Y14 protein families have undergone coevolution (Gong et al. 2014b). In this study, the similar topology of four gene families suggested that they might have undergone a similar evolutionary history. In addition, the simulated tetramer structures of the Physalis EJC core are conserved compared to those of animals. Therefore, EJC probably play fundamental roles in all of the eukaryotes. However, they play diverse roles in cell division, as well as physiological, developmental and adaptive roles, but were recruited in a species- or gene-specific manner (see “Introduction” section).

One possibility for the specificity in functions might involve the selective targets at transcription and different posttranscriptional levels such as localization, splicing and translation. In Drosophila, oskar mRNA proper localization is a primary target of EJC (Boswell et al. 1991; Newmark and Boswell 1994; Newmark et al. 1997; Micklem et al. 1997; van Eeden et al. 2001; Palacios et al. 2004). Depletion of EJC results in the skipping of several exons of mapk pre-mRNA, indicating the bias targeting of long intron genes (Ashton-Beaucage et al. 2010; Roignant and Treisman 2010). The GAAGA motif is a potential binding site for human EJC core eIF4AIII for gene expression regulation (Saulière et al. 2012). Mice MAGO plays a key function in brain size development by positively affecting microcephaly-associated lissencephaly-1 (LIS1) expression during neurogenesis (Silver et al. 2010). Y14 and MAG-1 control germ line sex determination by inhibiting the proper expression of the transformer-2 (TRA-2) protein in Caenorhabditis elegans (Shiimori et al. 2013). A few plant studies have shown that EJC primarily targets the splicing of the UDT1 transcript in rice and Physalis (Gong and He 2014; Huang et al. 2016). We found that plant EJC can affect transcription of genes associated with several specific pathways to produce related phenotypic variation in Physalis. The EJC homologues are closely interconnected at different levels, such as protein subcellular localization and protein dimerizations, to perform EJC functions in various organisms (Ashton-Beaucage et al. 2010; Roignant and Treisman 2010; Gong and He 2014; Choudhury et al. 2016). They can be interconnected at different steps of their own gene expression mechanisms in Arabidopsis (Mufarrege et al. 2011). This was not observed in rice or Physalis (Gong and He 2014; Huang et al. 2016). The differential extent of interconnection may contribute to the evolution of EJC diversity in function and mechanistic aspects. Examining more key species that reflect the phylogeny on the tree of life may contribute to understanding the evolutionary pattern of EJC targets and their related biological processes.

Conclusions

The EJC is an important complex playing roles in RNA metabolism during eukaryotic life. EJC core genes share similarities in sequences and evolutionary history, but they play diverse developmental roles in different eukaryotic life forms. One such role is floral development in plants. In this study, we found that the EJC core in Physalis is primarily involved in pollen developmental pathways and associated with female functionality determination, Chinese lantern development and defense-related responses (Fig. 8). A primary target for Physalis EJC core is PFDYT1, which encodes orthologs of UDT1, the key bHLH transcription factor in pollen development in rice and other plants (Jung et al. 2005; Gong and He 2014; Jeong et al. 2014; Huang et al. 2016). This supports the essential and conserved role of plant EJC in pollen development. Physalis EJC also affected the gene expression in the developmental processes. The newly discovered roles of Physalis EJC core genes in defense-related processes was linked to WRKY genes, while the roles in Chinese lantern morphology (PFeIF4AIII) and carpel functionality (PFY14) appeared to be gene-specific. This finding needs further investigation. Our results suggest that EJC is involved in gene expression regulation and mRNA metabolism of multiple developmental processes in Physalis, and provide novel insights into the understanding of the functional evolution of EJC core genes. Further studies will help us understand the basis for the diversity and specificity of EJC target genes and the biological processes that are involved in species such as P. floridana. The adaptive value of EJC for plants during their evolution could also be revealed by advanced studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Miss Chunjing Song for the assistance in preparing the Fig. 8a. Data deposition All relevant supporting data can be found within the additional files accompanying this article. Sequence data isolated in this article can be found in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) under the accessions of MH319840-MH319851.

Author Contributions

PCG and CYH designed the work. JL performed sequence isolation, gene expression and generated VIGS materials. PCG performed phylogenetic reconstruction, yeast-two hybrid, and BiFC analyses. PCG and JL performed genotyping and phenotyping of VIGS materials. PCG and CYH analyzed data and wrote the article. All authors read and approved the manuscript. CYH agrees to serve as the author responsible for contact and ensures communication.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant Nos. (31370259 and 31525003) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China to CYH.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

These authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Alachkar A, Jiang D, Harrison M, Zhou Y, Chen G, Mao Y. An EJC factor RBM8a regulates anxiety behaviors. Curr Mol Med. 2013;13:887–899. doi: 10.2174/15665240113139990019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen CB, Ballut L, Johansen JS, Chamieh H, Nielsen KH, Oliveira CL, et al. Structure of the exon junction core complex with a trapped DEAD-box ATPase bound to RNA. Science. 2006;313:1968–1972. doi: 10.1126/science.1131981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton-Beaucage D, Udell CM, Lavoie H, Baril C, Lefrançois M, Chagnon P, et al. The exon junction complex controls the splicing of MAPK and other long intron-containing transcripts in Drosophila. Cell. 2010;143:251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballut L, Marchadier B, Baguet A, Tomasetto C, Séraphin B, Le Hir H. The exon junction core complex is locked onto RNA by inhibition of eIF4AIII ATPase activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:861–869. doi: 10.1038/nsmb990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bono F, Ebert J, Lorentzen E, Conti E. The crystal structure of the exon junction complex reveals how it maintains a stable grip on mRNA. Cell. 2006;126:713–725. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothby TC, Wolniak SM. Masked mRNA is stored with aggregated nuclear speckles and its asymmetric redistribution requires a homolog of Mago nashi. BMC Cell Biol. 2011;12:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-12-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell RE, Prout ME, Steichen JC. Mutations in a newly identified Drosophila melanogaster gene, mago nashi, disrupt germ cell formation and result in the formation of mirror-image symmetrical double abdomen embryos. Development. 1991;113:373–384. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CC, Dostie J, Diem MD, Feng W, Mann M, Rappsilber J, et al. eIF4A3 is a novel component of the exon junction complex. RNA. 2004;10:200–209. doi: 10.1261/rna.5230104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazal PE, Daguenet E, Wendling C, Ulryck N, Tomasetto C, Sargueil B, et al. EJC core component MLN51 interacts with eIF3 and activates translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5903–5908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218732110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe J, Ryu I, Park OH, Park J, Cho H, Yoo JS, et al. eIF4AIII enhances translation of nuclear cap-binding complex-bound mRNAs by promoting disruption of secondary structures in 5′UTR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E4577–E4586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409695111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury SR, Singh AK, McLeod T, Blanchette M, Jang B, Badenhorst P, et al. Exon junction complex proteins bind nascent transcripts independently of pre-mRNA splicing in Drosophila melanogaster. eLife. 2016;5:e19881. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu FH, Chen YR, Lee CH, Chang TT. Molecular characterization and expression analysis of Acmago and AcY14 in Antrodia cinnamomea. Mycol Res. 2009;113:577–582. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang TW, Peng PJ, Tarn WY. The exon junction complex component Y14 modulates the activity of the methylosome in biogenesis of spliceosomal small nuclear ribonucleoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8722–8728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang TW, Chang WL, Lee KM, Tarn WY. The RNA-binding protein Y14 inhibits mRNA decapping and modulates processing body formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:1–13. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-03-0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang TW, Lee KM, Lou YC, Lu CC, Tarn WY. A point mutation in the exon junction complex factor Y14 disrupts its function in mRNA cap binding and translation enhancement. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:8565–8574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.704544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cilano K, Mazanek Z, Khan M, Metcalfe S, Zhang XN. A new mutation, hap1-2, reveals a C terminal domain function in AtMago protein and its biological effects in male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0148200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordin O, Banroques J, Tanner NK, Linder P. The DEAD-box protein family of RNA helicases. Gene. 2006;367:17–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui P, Chen T, Qin T, Ding F, Wang ZY, Chen H, et al. The RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain phosphatase-like protein FIERY2/CPL1 interacts with eIF4AIII and is essential for nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2016;28:770–785. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degot S, Le Hir H, Alpy F, Kedinger V, Stoll I, Wendling C, et al. Association of the breast cancer protein MLN51 with the exon junction complex via its speckle localizer and RNA binding module. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33702–33715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fribourg S, Gatfield D, Izaurralde E, Conti E. A novel mode of RBD-protein recognition in the Y14-Mago complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2003;10:433–439. doi: 10.1038/nsb926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Garcia E, Little JC, Kalderon D. The exon junction complex and Srp54 contribute to hedgehog signaling via ci RNA splicing in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2017;206:2053–2068. doi: 10.1534/genetics.117.202457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring NH, Lamprinaki S, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE. The hierarchy of exon-junction complex assembly by the spliceosome explains key features of mammalian nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Marchand V, Gaspar I, Ephurssi A. Control of RNP motility and localization by a splicing-dependent structure in oskar mRNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:441–449. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong PC, He CY. Uncovering divergence of rice exon junction complex core heterodimer gene duplication reveals their essential role in growth, development, and reproduction. Plant Physiol. 2014;165:1047–1061. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.237958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong PC, Quan H, He CY. Targeting MAGO proteins with a peptide aptamer reinforces their essential roles in multiple rice developmental pathways. Plant J. 2014;80:905–914. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong PC, Zhao M, He CY. Slow co-evolution of the MAGO and Y14 protein families is required for the maintenance of their obligate heterodimerization mode. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e84842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha JE, Choi YE, Jang J, Yoon CH, Kim HY, Bae YS. FLIP and MAPK play crucial roles in the MLN51-mediated hyperproliferation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. FEBS J. 2008;275:3546–3555. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachet O, Ephrussi A. Drosophila Y14 shuttles to the posterior of the oocyte and is required for oskar mRNA transport. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1666–1674. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00508-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- He CY, Saedler H. Heterotopic expression of MPF2 is the key to the evolution of the Chinese lantern of Physalis, a morphological novelty in Solanaceae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5779–5784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501877102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He CY, Sommer H, Grosardt B, Huijser P, Saedler H. PFMAGO, a MAGO NASHI-like factor, interacts with the MADS-box protein MPF2 from Phyaslis floridana. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1229–1241. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi K, Ishiga Y, Inagaki Y, Toyoda K, Shiraishi Y, Ichinose Y. Modulation of defense signal transduction by flagellin-induced WRKY41 transcription factor in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Genet Genom. 2008;279:303–312. doi: 10.1007/s00438-007-0315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SX, Gao YF, Liu JK, Peng XL, Niu XL, et al. Genome-wide analysis of WRKY transcription factors in Solanum lycopersicum. Mol Genet Genom. 2012;287:495–513. doi: 10.1007/s00438-012-0696-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CK, Sie YS, Chen YF, Huang TS, Lu CA. Two highly similar DEAD box proteins, OsRH2 and OsRH34, homologous to eukaryotic initiation factor 4AIII, play roles of the exon junction complex in regulating growth and development in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:84. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0769-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihsan H, Khan MR, Ajmal W, Ali GM. WsMAGO2, a duplicated MAGO NASHI protein with fertility attributes interacts with MPF2-like MADS-box proteins. Planta. 2015;241:1173–1187. doi: 10.1007/s00425-015-2247-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaki M, Kato D, Utsugi T, Onoda F, Hanaoka F, Murakami Y. Genetic analyses using a mouse cell cycle mutant identifies magoh as a novel gene involved in Cdk regulation. Genes Cells. 2011;16:166–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong HJ, Kang JH, Zhao MA, Kwon JK, Choi HS, Bae JH, et al. Tomato Male sterile 1035 is essential for pollen development and meiosis in anthers. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:6693–7609. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung KH, Han MJ, Lee YS, Kim YW, Hwang I, Kim MJ, et al. Rice Undeveloped Tapetum1 is a major regulator of early tapetum development. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2705–2722. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.034090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T, Kataoka N, Dreyfuss G, Sakamoto H. Ce-Y14 and MAG-1, components of the exon-exon junction complex, are required for embryogenesis and germline sexual switching in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech Dev. 2004;121:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kervestin S, Jacobson A. NMD: a multifaceted response to premature translational termination. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:700–712. doi: 10.1038/nrm3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KC, Lai Z, Fan B, Chen Z. Arabidopsis WRKY38 and WRKY62 transcription factors interacted with histone decetylase 19 in basal defense. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2357–2371. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroleva OA, Calder G, Pendle AF, Kim SH, Lewandowska D, Simpson CG, et al. Dynamic behavior of Arabidopsis eIF4A-III, putative core protein of exon junction complex: fast relocation to nucleolus and splicing speckles under hypoxia. Plant Cell. 2009;21:1592–1606. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.060434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau CK, Diem MD, Dreyfuss G, Van Duyne GD. Structure of the Y14-Magoh core of the exon junction complex. Curr Biol. 2003;13:933–941. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Hir H, Saulière J, Wang Z. The exon junction complex as a node of post-transcriptional networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:41–54. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Jung KH, An G, Chung YY. Isolation and characterization of a rice cysteine protease gene, OsCP1, using T-DNA gene-trap system. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;54:755–765. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000040904.15329.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski JP, Sheehan KB, Bennett PE, Jr, Boswell RE. Mago Nashi, Tsunagi/Y14, and Ranshi form a complex that influences oocyte differentiation in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 2010;339:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Boswell R, Wood WB. mag-1, a homolog of Drosophila mago nashi, regulates hermaphrodite germ-line sex determination in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 2000;218:172–182. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Zhang DS, Liu HS, Yin CS, Li XX, Liang WQ, et al. The rice tapetum degeneration retardation gene is required for tapetum degradation and anther development. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2999–3014. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Hong YB, Zhang YF, Li XH, Huang L, et al. Tomato WRKY transcriptional factor SlDRW1 is required for disease resistance against Botrytis cinerea and tolerance to oxidative stress. Plant Sci. 2014;227:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CC, Lee CC, Tseng CT, Tarn WY. Y14 governs p53 expression and modulates DNA damage sensitivity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45558. doi: 10.1038/srep45558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal A, Sarkar D, Kundu S, Kundu P. Mechanism of regulation of tomato TRN1 gene expression in late infection with tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus (ToLCNDV) Plant Sci. 2015;241:221–237. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micklem DR, Dasgupta R, Elliott H, Gergely F, Davidson C, Brand A, et al. The mago nashi gene is required for the polarisation of the oocyte and the formation of perpendicular axes in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 1997;7:468–478. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr SE, Dillon ST, Boswell RE. The RNA-binding protein Tsunagi interacts with Mago Nashi to establish polarity and localize oskar mRNA during Drosophila oogenesis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2886–2899. doi: 10.1101/gad.927001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MJ. From birth to death: the complex lives of eukaryotic mRNAs. Science. 2005;309:1514–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.1111443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufarrege EF, Gonzalez DH, Curi GC. Functional interconnections of Arabidopsis exon junction complex proteins and genes at multiple steps of gene expression. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:5025–5036. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar MS, Deslandes L, Auriac MC, Marco Y, Somssich IE. The Aradidopsis transcription factor WRKY27 influences wilt disease symptom development casued by Ralstonia solanacearum. Plant J. 2008;56:935–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark PA, Boswell RE. The mago nashi locus encodes an essential product required for germ plasm assembly in Drosophila. Development. 1994;120:1303–1313. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.5.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark PA, Mohr SE, Gong L, Boswell RE. mago nashi mediates the posterior follicle cell-to-oocyte signal to organize axis formation in Drosophila. Development. 1997;124:3197–3207. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.16.3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu N, Liang W, Yang X, Jin W, Wilson ZA, Hu J, et al. EAT1 promotes tapetal cell death by regulating aspartic proteases during male reproductive development in rice. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1445. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios IM, Gatfield D, St Johnston D, Izaurralde E. An eIF4AIII-containing complex required for mRNA localization and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nature. 2004;427:753–757. doi: 10.1038/nature02351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SP, Roccaro M, Schön M, Logemann E, Somssich IE. Transcriptional reprogramming regulated by WRKY18 and WRKY40 facilitates powdery mildew infection of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2010;64:912–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park NI, Yeung EC, Muench DG. Mago nashi is involved in meristem organization, pollen formation, and seed development in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2009;176:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parma DH, Bennett PE, Jr, Boswell RE. Mago Nashi and Tsunagi/Y14, respectively, regulate Drosophila germline stem cell differentiation and oocyte specification. Dev Biol. 2007;308:507–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascuan C, Frare R, Alleva K, Ayub ND, Soto G. mRNA biogenesis-related helicase eIF4AIII from Arabidopsis thaliana is an important factor for abiotic stress adaptation. Plant Cell Rep. 2016;35:1205–1208. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-1947-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]