Abstract

Introduction

The primary mechanism through which the development of exercise-associated hyponatraemia (EAH) occurs is excessive fluid intake. However, many internal and external factors have a role in the maintenance of total body water and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) have been implicated as a risk factor for the development of EAH. This study aimed to compare serum sodium concentrations ([Na]) in participants taking an NSAID before or during a marathon (NSAID group) and those not taking an NSAID (control group).

Methods

Participants in a large city marathon were recruited during race registration to participate in this study. Blood samples and body mass measurements took place on the morning of the marathon and immediately post marathon. Blood was analysed for [Na]. Data collected via questionnaires included athlete demographics, NSAID use and estimated fluid intake.

Results

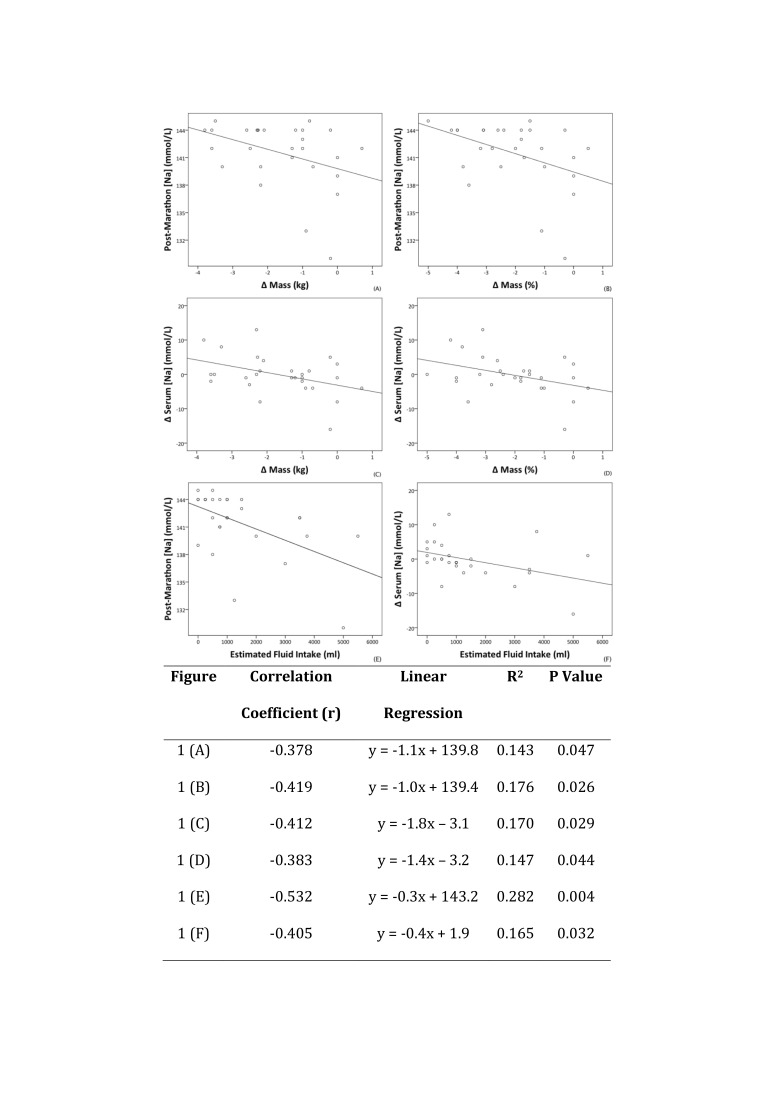

We obtained a full data set for 28 participants. Of these 28 participants, 16 took an NSAID on the day of the marathon. The average serum [Na] decreased by 2.1 mmol/L in the NSAID group, while it increased by 2.3 mmol/L in the control group NSAID group (p=0.0039). Estimated fluid intake was inversely correlated with both post-marathon serum [Na] and ∆ serum [Na] (r=−0.532, p=0.004 and r=−0.405 p=0.032, respectively).

Conclusion

Serum [Na] levels in participants who used an NSAID decreased over the course of the marathon while it increased in those who did not use an NSAID. Excessive fluid intake during a marathon was associated with a lower post-marathon serum [Na].

Keywords: Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia, EAH, Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatories, NSAID, Fluid

What are the new findings?

Over the course of a marathon, serum [Na] is more likely to fall in participants who use an non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAID) than in those who don’t.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the near future?

A better understanding of the additional risks of using NSAIDs during exercise will inform future guidelines to make marathon running a safer activity

Introduction

Exercise-associated hyponatraemia (EAH) is a potentially life-threatening cause of collapse during and after endurance exercise.1 2 It is defined as a serum sodium concentration ([Na]) below that of the laboratory reference range (commonly 135 mmol/L) during or up to 24 hours following prolonged physical activity.3

Risk factors in the development of EAH tend to be related to fluid balance. In most cases, EAH is caused by overhydration during exercise which can result in a haemodilution and subsequent decrease in blood sodium concentration.4 5 Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) indirectly potentiate the water retention effects of vasopressin through reduction in prostaglandin synthesis and subsequent reduced renal blood flow.6 7 Change in body mass can be used as a marker of hydration status after prolonged endurance exercise, such as a marathon. Participants who do not lose weight, or indeed gain weight, over the course of the marathon are likely to be overhydrated and are at greater risk of developing EAH.8–10 The American College of Sports Medicine recommend aiming for <2% body mass loss during sporting events to maintain hydration status.11 12

Despite the well-documented medical risks of using NSAIDs, NSAIDs are widely available without prescription. Previous studies have found that between 30% and 50% of competitors will use NSAIDs before or during events.13–17 Several authors have observed an association between NSAID use and development of EAH,14 18 19 although other studies specifically investigating EAH risk factors have found no correlation between use of NSAIDs and EAH.7 20 21 This uncertainty in the relationship between NSAIDs and EAH prompted the Third International EAH Consensus Conference to recommend further research in this area.3

The aim of this study was to compare the effect of NSAID use on changes in serum [Na] following a marathon. It was hypothesised that participants using NSAIDs before or during a marathon would have a greater reduction in serum [Na] (post-marathon serum [Na] – pre-marathon serum [Na]) than participants who did not use an NSAID.

Methods

Study setting

This study took place during a 26.2 mile city marathon which runs annually in late spring in the UK. The average daytime temperature on race-day was 6°C (3°C–10°C), the average humidity was 58% (31%–88%) and there was 0.2 mm of rainfall.22 There were several drinks stations along the route including water in 250 mL bottles every mile from mile 3 to mile 25 and 380 mL sports drinks at miles 5, 10, 15, 19 and 23. Final instructions from the marathon organisers which included guidelines on safe drinking habits (eg, to drink according to thirst) and recommendations to avoid NSAID use during the marathon were sent to all participants in print and were also available to read online.

Study design

A sample size calculation was used to calculate the number of participants required in the study in order to compare the change in serum [Na] from pre-marathon sampling to post-marathon sampling (∆ serum [Na]) in participants taking NSAIDs (NSAID group) and participants not taking NSAIDs (control group). A mean ∆ serum [Na] difference of 3 mmol/L was deemed significant. The SD was set at 2 mmol/L as this value has been used in previous research.23 The result found a sample size of 10 participants per group allowed 90% statistical power (1 - beta) with a significance level set at 5%.

Marathon participants were approached at random during marathon registration, which took place over the 4 days prior to the marathon and invited to participate in the study. All registered entrants in the marathon were eligible for our study, and we deemed that participation in the marathon implied that participants were fit and healthy. Participants under 18 years of age were ineligible to enter the marathon and therefore were not included our study. Consent for participation and blood testing was obtained. Participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire.

On the day of the marathon, immediately prior to starting, all participants completed a brief questionnaire had their body mass measured wearing race clothing and running shoes on a Seca 803 Clara Digital Scale, accurate to 0.1 kg, and had a 5 mL blood sample drawn.

After crossing the finish line, participants had their body mass measured using the same scales. A second 5 mL venous blood sample was drawn, and participants completed a brief questionnaire documenting estimated fluid intake, medication use, and where appropriate, NSAID dose.

Data regarding intended NSAID use were collected at race registration and again at the start line. Questions regarding participants knowledge of NSAID risk and safe dose were asked on the post-marathon questionnaire in order to reduce response bias. No instructions were given to participants with regards to NSAID use or NSAID dose. Risk awareness was categorised as correct if participants were able to name at least one correct risk or side effect from any NSAID. Dose awareness was categorised as correct if participants knew the maximum dose of the NSAID they had used. Maximum daily doses of medication were obtained from the British National Formulary.24 Doses of NSAIDs are presented relative to the maximum daily recommended dose.

Fluid intake was estimated from the participants recall of the number of water and sports drink bottles picked up at fluid stations over the course of the marathon. Furthermore, it was based on the assumption that all bottles were completely consumed.

Venous blood samples were collected from an antecubital vein in a seated position into a Startstedt-Monovette Z-Gel vacutainer system. Blood samples were stored upright for 30–60 min before being centrifuged (2500 rpm for 10 min) using a Hettich Zentrifugen Rotofix 32. Thereafter bloods were stored upright in a cooling bag for transport to the laboratory for analysis. Sodium, potassium, urea and creatinine concentrations were measured in duplicate using indirect ion selective electrode (Siemens ADVIA 2400, Siemens, Berlin: Germany; CV<1.1%).

Outcome measures

The laboratory’s normal reference range for [Na] was 133–146 mmol/L. NSAID use was a key independent variable. Other variables included age, body mass change, estimated fluid intake, marathon time and number of previous marathons.

Statistical analysis

Statistics were calculated using IBM SPSS V.23. Continuous variables, categorical and non-parametric variables were compared using t-tests, χ2 tests and Mann-Whitney U tests, respectively. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to analyse relationships between variables. Multivariate analysis, using analysis of variance, further analysed the dependent variable ‘change in serum [Na] with the independent variables ‘NSAID use’ and ‘percentage mass change’. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. Data were recorded as mean±SD, unless stated otherwise.

Results

Recruitment

A total of 109 participants were recruited during marathon registration. A subset of 41 participants reported to the research station at the start line for pre-marathon baseline tests. All 41 participants completed the marathon and 28 participants returned for data collection after crossing the finish line. Therefore, a complete dataset for 28 participants was obtained. There were no significant differences in age, gender, body mass, number of previous marathons or finish times between the 28 participants who completed the study and the 13 participants who did not attend the research station after the finish line.

NSAID use and their effect on serum biochemistry

At race registration, 50 of the 109 (45.9%) participants stated that they intended to use an NSAID on race day and/or during the marathon. At the start line, 11/28 (39%) participants had used an NSAID on the morning of the marathon. Also, 8 of the 28 (29%) participants used an NSAID during the marathon. In total, 16 of the 28 (57.1%) participants completing the study used an NSAID either before or during the marathon, or both.

Participants were grouped into those who took an NSAID before or during the marathon (‘NSAID group’) and those who did not take an NSAID (‘control group’). The NSAID group comprised 6 females and 10 males. The control group (n=12) had only one female (table 1).

Table 1.

Participant demographics, body mass, fluid intake and marathon time data

| Complete finish line cohort (n=28) |

NSAID group (n=16) |

Control group (n=12) |

P value* | |

| Age (years) | 45±9 | 43±8 | 47±11 | 0.316 |

| Male:female | 21:7 | 10:6 | 11:1 | 0.058 |

| Body mass (kg) | 79.0±16.8 | 77.8±18.8 | 80.8±14.4 | 0.649 |

| Caucasian ethnicity, n (%) | 23 (82.1) | 13 (81.2) | 12 (100) | 0.112 |

| Number of prior marathons completed | 6±13 | 4±10 | 7±16 | 0.532 |

| Estimated fluid intake during the marathon (L) | 1.4±1.5 | 1.7±1.6 | 1.0±1.5 | 0.309 |

| Race time (min) | 276.0±48.0 | 276.8±45.6 | 281.0±58.7 | 0.834 |

| Absolute body mass change (kg) | −1.6±1.3 | −1.4±1.3 | −1.9±1.2 | 0.376 |

| Relative body mass change (%) | −2.1±1.5 | −1.9±1.6 | −2.3±1.4 | 0.568 |

*P values are given for analysis between the NSAID and control groups. NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications.

Both groups finished the marathon in similar times (p=0.834) and estimated consuming similar volumes of fluid per person (p=0.309). There was no significant difference in absolute or relative body mass change between groups (p=0.376 and 0.568, respectively) over the course of the marathon. There was no difference in either pre-marathon or post-marathon serum (Na) between groups (table 2). However, serum (Na) levels in the NSAID group decreased by an average of 1.5% compared with an average 1.6% increase in serum (Na) in the control group. No differences were seen in either pre-marathon or post-marathon serum potassium, urea or creatinine between groups; nor were changes in these parameters over the course of the marathon significant (data not shown).

Table 2.

A comparison of athlete blood results in the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAID) and control groups [a]. These were then subdivided into those taking an NSAID the morning of the marathon (mNSAID group) [b] and those taking an NSAID during the marathon (dNSAID group) [c]

| [a] NSAID use before or during the marathon | |||

| NSAID group (n=16) | Control group (n=12) | P value | |

| Pre-marathon [Na] (mmol/L) | 142.8±4.1 | 140.2±4.4 | 0.114 |

| Post-marathon [Na] (mmol/L) | 140.8±4.4 | 142.5±1.8 | 0.161 |

| ∆ [Na) (mmol/L) | −2.1±5.7 | 2.3±4.7 | 0.039 |

| [b] NSAID use the morning of the marathon | |||

| NSAID group (n=11) | Control group (n=17) | P value | |

| Pre-marathon [Na] (mmol/L) | 142.2±4.6 | 141.4±4.3 | 0.633 |

| Post-marathon [Na] (mmol/L) | 141.4±3.7 | 141.6±3.6 | 0.874 |

| ∆ [Na] (mmol/L) | −0.8±4.7 | 0.2±6.3 | 0.639 |

| [c] NSAID use during the marathon | |||

| NSAID group (n=8) | Control group (n=20) | P value | |

| Pre-marathon [Na] (mmol/L) | 144.0±2.6 | 140.8±4.6 | 0.074 |

| Post-marathon [Na] (mmol/L) | 140.9±4.9 | 141.8±3.0 | 0.566 |

| ∆ [Na] (mmol/L) | −3.1±6.3 | 1.0±5.1 | 0.081 |

∆, Change from pre-marathon to post-marathon; [Na], Sodium concentration.

There was a significant difference in the change in serum [Na] between the NSAID and control groups (p=0.039, table 2). Multiple linear regression suggested a possible correlation between the dependent variable ∆ serum [Na] and the independent variables percentage body mass change (beta=−0.34, p=0.057) and NSAID use (beta=−0.35, p=0.051); however, this did not quite reach significance. Participants who used an NSAID during the marathon tended to reduce serum [Na] over the course of the marathon. However there was no difference in serum [Na] between those who used an NSAID on the morning of the marathon (mNSAID group) and those who used an NSAID during the marathon (dNSAID group) (table 2).

Athlete knowledge of NSAIDs

Ibuprofen was the most commonly used NSAID (n=14). The total dose of ibuprofen taken on the day of the marathon ranged from 200 to 1800 mg (for reference the recommended maximum daily dose is 2400 mg24). One participant used two different NSAIDs during the marathon (ibuprofen and diclofenac). Reasons given for taking NSAIDs included treating a pre-existing injury (n=7), prophylactic pain management (n=6) and perceived improvements in performance (n=3). 37.5% of the participants who used an NSAID were aware of the safe dose and 50% were aware of at least one NSAID-related risk. There were no differences in safe NSAID dose knowledge and NSAID risk awareness between the two groups (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparisons of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAID) knowledge in the NSAID and control group

| NSAID group (n=16) | Control group (n=12) | P value | |

| Correct awareness of NSAID risks, n (%) | 8 (50) | 5 (41.7) | 0.662 |

| Correct awareness of NSAID safe dose, n (%) | 6 (37.5) | 4 (33.3) | 0.820 |

| Consumed more than recommended safe limit of NSAID, n (%)* | 6 (37.5) | – | – |

*Dose exceeding the maximum safe limit for a single dose as per the British National Formulary.24

Other risk factors for EAH

Fluid intake was expressed relative to pre-marathon body mass (fluid intake/body mass) and compared with post-marathon serum [Na] and change in serum [Na]. Significant correlations were found in both cases (R=−0.581, p=0.001 and R=−0.448, p=0.017). However, there was no significant differences in fluid intake/body mass between the NSAID and control groups.

Those in whom the serum [Na] fell over the course of the marathon were relatively inexperienced compared with participants in whom the serum [Na] did not fall (average of 2 previous marathons vs 12 previous marathons, respectively, p=0.063). There were no significant differences in marathon experience between the NSAID and control groups (table 1).

There were no other significant differences in between these two groups, including gender, race time, body mass or age. Other than NSAIDs, no participants were taking any regular medications.

Incidence of EAH

One of the 28 participants (3.5%) had a post-race serum [Na] of 130 mmol/L meeting the criteria for EAH. The pre-race serum [Na] was 146. This participant reported using 800 mg ibuprofen and estimated consuming 5 L of fluid during the marathon and lost only 0.3% body mass. The race time for this participant was 4 hours 56 min. The participant remained asymptomatic and reported no subsequent effects (personal correspondence).

Correlations of serum sodium concentration

Estimated fluid intake and body mass changes were inversely correlated with both post-marathon serum [Na] and ∆ serum [Na] (figure 1). There were no significant correlations between estimated fluid intake and either absolute body mass change (r=0.110, p=0.579) or relative body mass change (r=0.161, p=0.396). Furthermore, marathon time did not correlate with either absolute or relative body mass change (r=0.008, p=0.966 and r=0.000, p=0.998, respectively).

Figure 1.

Correlations between changes in serum (Na), body mass changes and estimated fluid intake. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and regression analysis for the respective graphs are illustrated in the underlying table.

Finally, no significant correlations were identified between race time and ∆ serum [Na] and post-marathon [Na] (r=−0.257, p=0.186 and r=0.032, p=0.871, respectively).

Discussion

Our main findings were a high prevalence of NSAID use among marathon participants before or during the marathon. Participants who consumed an NSAID before or during the marathon demonstrated a significantly greater reduction in serum [Na] over the course of the marathon compared with those participants who did not use an NSAID (table 2). Fluid intake and change in body mass both correlated with post-marathon serum [Na] and with ∆ serum [Na] (figure 1). One participant met the criteria for EAH.

Prevalence of NSAID use at marathons

The marathon provides written medical guidance to all participants which includes specific advice on fluid intake and recommendations to avoid using NSAIDs before or during the race. Despite this, 57% of this small study cohort used an NSAID on marathon day.

Participants in this present study commonly cited prophylactic pain management as a reason for using NSAIDS, although previous research has shown that NSAIDs do not prevent delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) after a marathon.13 This lack of benefit could be explained by the short half-life of NSAIDs.25 The half-life of ibuprofen is only 2 hours, and therefore it is unlikely to exert much analgesic effect past 4 hours, the average duration of a marathon.26 This short half-life may be a reason participants take more than one dose during a marathon, and thus consume doses above the recommended safe maximum. Also, 50% of athletes using NSAIDs were unaware of the risks of NSAID use, and 37.5% of NSAID users consumed doses greater than the recommended safe maximum.

It is important to consider the clinical significance of the small changes in serum [Na] observed in this study. A difference in 4.4 mmol/L is unlikely to be of clinical significance. This difference may be of greater clinical significance when combined with other risk factors, such as increased fluid intake.

The effect of NSAIDs on serum sodium concentration

In the present study serum [Na] decreased by 2.1 mmol/L in NSAID users over the course of the marathon, while it increased by 2.3 mmol/L in non-NSAID users (p=0.039). This appears to contrast with a large cohort study of >400 participants which found no association between NSAID use and the development of EAH.7 However, it should be noted that the definition of NSAID use in in this large cohort study included use up to 7 days prior to the marathon and did not differentiate between NSAID use in the days prior to the marathon and use during the marathon.7

A subgroup analysis was performed on the effect of NSAID use prior to or during the marathon. In a subgroup analysis on participants in this study, serum [Na] fell further in participants who used an NSAID during the marathon (3.1 mmol/L) compared with those who only used an NSAID before starting the marathon (0.8 mmol/L)(table 2). This affect may be a consequence of the short half-life of NSAIDs.26 No significant correlations were found between serum [Na] and the dose of NSAIDs used.

The NSAID group did consume 0.7 L more fluid than the control group. Furthermore, the NSAID group lost 0.4% less weight than the control group. Despite both these differences not reaching clinical significance, this may present a confounder.

Fluid intake, body mass changes and serum sodium concentrations

Body mass change is commonly used in field-based studies as marker of hydration and is used as a surrogate measure for fluid balance during a race. Several authors have described inverse correlations between body mass change and serum [Na].7 8 21 27 28 Furthermore, studies have described inverse correlations between fluid intake and serum [Na].12 29 Our study replicated these findings, providing further evidence to show inverse relationships between serum [Na] indices and estimated fluid intake, and between serum [Na] and body mass change. There was no difference in either estimated fluid intake or body mass change between those who used NSAIDs and those who did not use NSAIDs.

Incidence of EAH

One participant met the criteria for EAH. He estimated that he had consumed approximately 5 L and 800 mg of ibuprofen before and during the marathon. His race time was 4 hours 56 min, slightly slower than the average race time of all study participants 4 hours 38 min. Given increased fluid intake is a significant factor in the development of EAH; this is likely to have significantly influenced his serum [Na] during and after the marathon. It is interesting to note that several other athletes in this study estimated that they had consumed similar volumes of fluid, but did not use NSAIDs, yet their serum [Na] were not significantly affected adding further weight to the possible role of NSAIDs in the development of EAH.

Limitations and implications for future research

Participants were presumed medically fit and healthy as they were taking part in a marathon. As a result, unidentified comorbidities may have been present. Normal pre-race serum [Na] reduced the likelihood that participants were truly unwell on the day of the marathon.

Fluid intake during the marathon relied on athlete recall which is subject to bias. To minimise this limitation, body mass was measured immediately before and after the marathon to complement fluid intake data. Data regarding NSAID use were also collected retrospectively. Furthermore, NSAID type and dose was not controlled or accounted for in the main analysis.

There was large dropout rate between race registration and the start of the marathon. In addition, 13 participants did not attend the finish line research station for data collection. Attempts were made to contact participants who did not attend for post-race testing. Several cited difficulties locating the research station among busy crowds. This loss to follow-up resulted in small final groups and therefore accuracy of results may have been affected.

Although the same scales were used to measure participants body mass, running shoes were not removed. Accumulation of fluid (eg, sweat) within the fabric of the clothes and shoes may have affected apparent post-marathon body mass potentially underestimating body mass loss. This may offer an explanation for the lack of body mass changes seen in some participants.

Female gender is a known risk factor for EAH, and the higher proportion of females to males in the NSAID group than the control group may have skewed the results. It is possible the increased risk related to female gender represents an association due to volume of fluid relative to females’ smaller size rather than a risk factor per se.

Further research is required to establish if NSAIDs taken post-event cause similar effects on serum sodium levels in the 24 hours following exercise.

Conclusion

Fifty-seven percent of a cohort of 28 marathon participants used NSAIDS before or during a marathon despite cautionary advice from the marathon organisers to avoid their use. There was a significant reduction in serum [Na] over the course of the marathon in participants who used NSAIDS while athletes who did not use NSAIDs demonstrated an increase in serum [Na]. Estimated fluid intake and changes in body mass were inversely correlated with both post-marathon serum [Na] and ∆ serum [Na]. Only half the athletes using NSAIDs were aware of the risks of NSAID use, and 37.5% of NSAID users consumed doses greater than the recommended safe maximum.

Acknowledgments

In addition to the authors of this paper Dr Alex Maxwell, Angela McIllMurray, Dr Bethan Griffiths, Dr Emily Kidd, Jenny Baker, Dr Jonathan Hall, Nikhil Patel, Dr Rachel Parker and Dr Tom Lyon assisted during data collection. The project was awarded the British Association of Sports Medicine (BASEM) 2016 Research Bursary, which helped towards the expenses of the project. University College London (UCL) provided the remaining funds for the projects expenses. The authors would like to thank all participants, helpers, BASEM and UCL.

Footnotes

Contributors: SW: data collection, analysis and article write up. SM: data collection and review/editing of article. CK: supervisor, review/editing of article.

Funding: This project received funding from the University College London (UCL) and the British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine (BASEM).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: UCL Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All collated data are available to all researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal and have the appropriate approval. Data will be available immediately following publication, for 5 years. Proposals should be directed to steven.whatmough@nhs.net. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

References

- 1. Ayus JC, Varon J, Arieff AI, et al. Hyponatremia, cerebral edema, and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema in marathon runners. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:711–4. 10.7326/0003-4819-132-9-200005020-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thompson J-A, Wolff AJ. Hyponatremic encephalopathy in a marathon runner. Chest 2003;124:313S 10.1378/chest.124.4_MeetingAbstracts.313S [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hew-Butler T, Rosner MH, Fowkes-Godek S, et al. Statement of the third international exercise-associated hyponatremia consensus development conference, Carlsbad, California, 2015. Clin J Sport Med 2015;25:303–20. 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B, et al. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2014;29(suppl_2):i1–i39. 10.1093/ndt/gfu040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, et al. Hyponatremia treatment guidelines 2007: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med 2007;120(11 Suppl 1):S1–S21. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rüst CA, et al. Regulation of electrolyte and fluid metabolism in multi-stage ultra-marathoners. Horm Metab Res 2012;44:919–26. 10.1055/s-0032-1312647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Almond CS, Shin AY, Fortescue EB, et al. Hyponatremia among runners in the Boston Marathon. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1550–6. 10.1056/NEJMoa043901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Noakes TD, Sharwood K, Speedy D, et al. Three independent biological mechanisms cause exercise-associated hyponatremia: evidence from 2,135 weighed competitive athletic performances. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:18550–5. 10.1073/pnas.0509096102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoffman MD, Fogard K, Winger J, et al. Characteristics of 161-km ultramarathon finishers developing exercise-associated hyponatremia. Res Sports Med 2013;21:164–75. 10.1080/15438627.2012.757230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bruso JR, Hoffman MD, Rogers IR, et al. Rhabdomyolysis and hyponatremia: a cluster of five cases at the 161-km 2009 Western States Endurance Run. Wilderness Environ Med 2010;21:303–8. 10.1016/j.wem.2010.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Casa DJ, Clarkson PM, Roberts WO, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on hydration and physical activity: consensus statements. Curr Sports Med Rep 2005;4:115–27. 10.1097/01.CSMR.0000306194.67241.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Montain SJ, Cheuvront SN, Sawka MN, et al. Exercise associated hyponatraemia: quantitative analysis to understand the aetiology. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:98–105. 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Küster M, Renner B, Oppel P, et al. Consumption of analgesics before a marathon and the incidence of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and renal problems: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002090 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wharam PC, Speedy DB, Noakes TD, et al. NSAID use increases the risk of developing hyponatremia during an Ironman triathlon. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006;38:618–22. 10.1249/01.mss.0000210209.40694.09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martínez S, Aguiló A, Moreno C, et al. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs among participants in a mountain ultramarathon event. Sports 2017;5:11 10.3390/sports5010011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Joslin J, Lloyd JB, Kotlyar T, et al. NSAID and other analgesic use by endurance runners during training, competition and recovery. South African Journal of Sports Medicine 2013;25:101–4. 10.17159/2078-516X/2013/v25i4a340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gorski T, Cadore EL, et al. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in triathletes: Prevalence, level of awareness, and reasons for use. Br J Sports Med 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Davis DP, Videen JS, Marino A, et al. Exercise-associated hyponatremia in marathon runners: a two-year experience. J Emerg Med 2001;21:47–57. 10.1016/S0736-4679(01)00320-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cairns RS, Hew-Butler T. Incidence of exercise-associated hyponatremia and its association with nonosmotic stimuli of arginine vasopressin in the GNW100s ultra-endurance marathon. Clin J Sport Med 2015;25:347–54. 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Page AJ, Reid SA, Speedy DB, et al. Exercise-associated hyponatremia, renal function, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use in an ultraendurance mountain run. Clin J Sport Med 2007;17:43–8. 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31802b5be9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scotney B, Reid S. Body weight, serum sodium levels, and renal function in an ultra-distance mountain run. Clin J Sport Med 2015;25:341–6. 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meteorological-Office Meteorological office archive. [Online] [Accessed 6 June 2018].

- 23. Stachenfeld NS, Taylor HS. Sex hormone effects on body fluid and sodium regulation in women with and without exercise-associated hyponatremia. J Appl Physiol 2009;107:864–72. 10.1152/japplphysiol.91211.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Joint Formulary Committee British National Formulary (online). London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nieman DC, Henson DA, Dumke CL, et al. Ibuprofen use, endotoxemia, inflammation, and plasma cytokines during ultramarathon competition. Brain Behav Immun 2006;20:578–84. 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bushra R, Aslam N. An overview of clinical pharmacology of Ibuprofen. Oman Med J 2010;25:155–661. 10.5001/omj.2010.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jones BL, OʼHara JP, Till K, et al. Dehydration and hyponatremia in professional rugby union players: a cohort study observing english premiership rugby union players during match play, field, and gym training in cool environmental conditions. J Strength Cond Res 2015;29:107–15. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sharwood K, Collins M, Goedecke J, et al. Weight changes, sodium levels, and performance in the South African Ironman Triathlon. Clin J Sport Med 2002;12:391–9. 10.1097/00042752-200211000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kipps C, Sharma S, Tunstall Pedoe D, et al. The incidence of exercise-associated hyponatraemia in the London marathon. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:14–19. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.059535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]