Abstract

Previous reviews have indicated that immigration from South Asian to Western countries leads to unhealthy changes in diet; however, these reviews have been limited by the methods used in some included studies. This critical narrative review summarizes findings from original research articles that performed appropriate statistical analyses on diet data obtained using culturally appropriate diet assessment measures. All studies quantitatively compared the diets of South Asian immigrants with those of residents of Western or South Asian countries or with those of South Asian immigrants who had varying periods of time since immigration. Most studies examined total energy and nutrient intake among adults. Total energy intake tended to decrease with increasing duration of residence and immigrant generation, and immigrants consumed less protein and monounsaturated fat compared with Westerners. However, findings for intakes of carbohydrate, total fat, saturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, and micronutrients were mixed. Studies that examine food group intake and include South Asians living in South Asia as a comparison population are needed.

Keywords: diet, ethnicity, immigration, South Asian

INTRODUCTION

South Asians account for approximately 25% of the world’s 7.3 billion individuals.1 Although the majority of South Asians reside in South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Afghanistan, or the Maldives), increasingly more South Asians reside in Western countries (North and South America, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand). South Asians represent the largest nonwhite ethnic group in the United Kingdom2 and Canada,3 constituting approximately 5% of each country’s total population, and are among the fastest-growing ethnic groups in the United States4 and New Zealand.5 While population growth among residents partially explains this rise in prevalence, immigration is also a key factor, as South Asians are one of the 3 largest immigrant groups to the United Kingdom,6 Canada,3 the United States,7 and New Zealand.5

Compared with whites of the same body mass index, South Asians are at increased risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.8 Immigration by South Asians to a Western country results in new exposures to food availability and to cultural norms of food preparation methods.9 These exposures, along with other lifestyle influences, are thought to encourage changes in dietary habits,10 leading immigrants to experience excess weight gain that elevates their risk of obesity11 and related chronic diseases.12,13 Dietary change following immigration has been identified as a potential modifiable risk factor for obesity and obesity-related disease in this population.14

Three previous reviews have summarized the diets of South Asian immigrants living in Western countries, but 1 was based on a very small number of studies9 and 2 were largely qualitative.10,15 Furthermore, the study design and statistical analysis methods used in the reviewed studies were not examined to ensure that the effects of known confounders of the associations under study were considered. In addition, none of these reviews critically evaluated the diet methodology to ensure that instruments were culturally appropriate.9,10,15

The purpose of this review is to update and extend previous reviews of diet in South Asians who immigrate to a Western country, with careful attention given to crucial aspects of study methodology. Limitations of relevant studies that failed to conduct appropriate statistical analyses or use culturally relevant diet assessment measures are identified. The findings of only those studies that met the criteria for quality evaluation are then summarized. The aim was to present a critical, rather than systematic, review of the literature.16

Search process

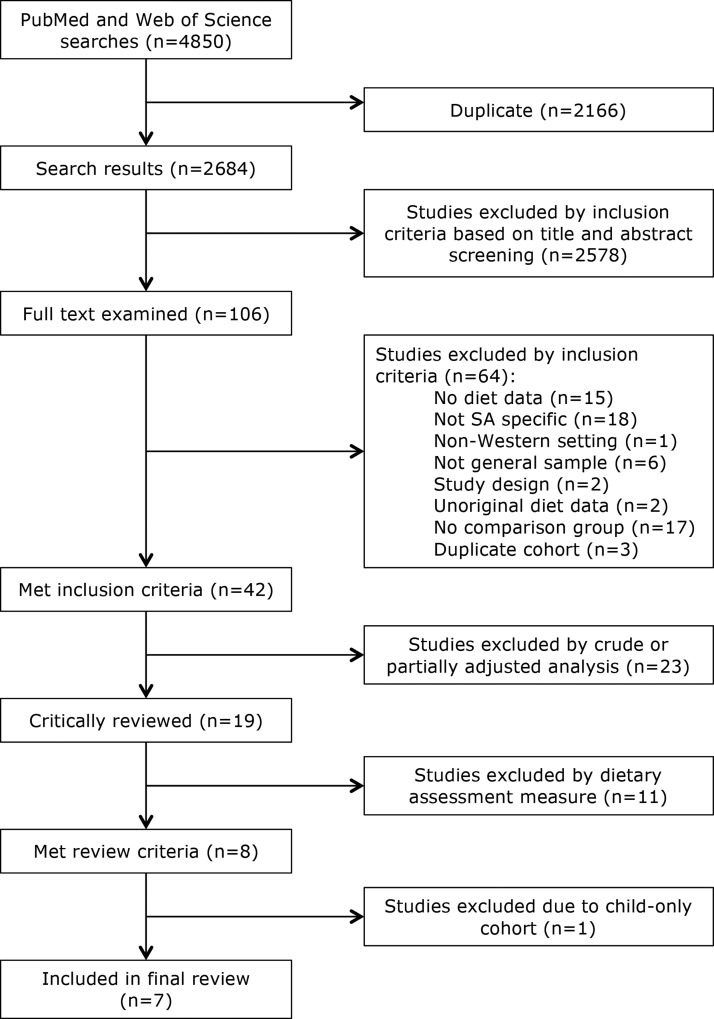

Details of the literature search process are shown in Figure 1. Briefly, the PubMed and Web of Science databases were searched for studies that examined diet in South Asians following immigration to Western countries. The review was limited to relevant articles published between January 1, 1990, and April 18, 2016. Observational studies and interventions that analyzed baseline data were retained if participants were recruited from the general population and if original diet data was used to quantitatively compare South Asian immigrants with a Western population, with other South Asian immigrants living in the same Western country, or with South Asians living in South Asia. Four publications presented diet data from the same cohort17–20; only the one that analyzed diet data with ethnicity as the main exposure was retained.17 This process resulted in the identification of 42 articles for further review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search process.

Critical review of statistical analyses

Previous literature has identified age and sex as important confounders of comparisons of diets of recent vs long-term South Asian immigrants9,21 and of South Asian immigrants vs Westerners.22–24 Given these associations, studies were required to either adjust for or stratify by age and sex in order to be included in the summary of key comparisons. Of the 42 articles, 6 were excluded because no statistical analysis of the diet data was presented. Thirteen were excluded because they reported only crude analyses without adjustment for any covariates. Four additional studies did not adjust for age. Following these exclusions, 19 articles were retained for review of diet assessment methodology.

Critical review of diet assessment methods

Table 1 17 , 21–38 shows descriptive information on the 19 studies that were reviewed for diet methodology, arranged by the comparison population. Table 217,21–59 summarizes the development and validation of the diet assessment measures implemented in the remaining 19 relevant articles, organized by the diet methodology used. The following methods were used to collect diet data: (1) food diaries; (2) single 24-hour recalls; (3) food frequency questionnaires (FFQs); and (4) other questionnaires. Different methods were used in each publication except in instances in which the data were from the same study. Three articles by Pomerleau et al.24,30,31 used data from the same cohort, 2 of which described intakes of different macronutrients and 1 of which reported intakes in servings and as a percentage of persons meeting dietary recommendations.24 Bharmal et al.,33 Sarwar et al.,35 and Becerra et al.38 reported similar aspects of diet using overlapping years of data from the same survey and used different comparison groups.

Table 1 .

Description of the 19 studies of diet in South Asian immigrants that met criteria for relevance and statistical analysis

| Reference | Comparison population(s) | Western country | Sample size | Percent male | Age (y) | Ethnicity | Country of origin | Immigrant generation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simmons & Williams (1997)25 | European | UK | 304 | 43 | ≈ 54 | European | – | – |

| 308 | 52 | ≈ 43 | South Asian | |||||

| Anderson et al. (2005)26 | European | UK | 35 | 0 | 28 | European | I, P, B | 1st/2nd |

| 72 | 0 | ≈ 29 | South Asian | |||||

| 35 | 0 | 31 | 1st-gen South Asian | |||||

| 37 | 0 | 27 | 2nd-gen South Asian | |||||

| Sevak et al. (1994)27,a | European | UK | 81 | 100 | 40–64 | European | I, P, B | – |

| 92 | 100 | 40–64 | South Asian | |||||

| Stone et al. (2007)22,a | White European | UK | 409 | – | 11–15 | European | – | – |

| 2460 | – | 11–15 | South Asian | |||||

| Donin et al. (2010)17,a | White European | UK | 543 | 50 | 9–10 | European | I, P, B, SL | – |

| 558 | 47 | 9–10 | South Asian | |||||

| Smith et al. (2012)28,b | White European | UK | 8353 | 48 | 36 | European | I, P, B | 1st/2nd |

| 2298 | ≈ 45 | ≈ 32 | South Asian | |||||

| 368 | 43 | 38 | 1st-gen Indian | |||||

| 349 | 46 | 33 | 2nd-gen Indian | |||||

| 395 | 46 | 36 | 1st-gen Pakistani | |||||

| 475 | 46 | 27 | 2nd-gen Pakistani | |||||

| 351 | 47 | 33 | 1st-gen Bangladeshi | |||||

| 360 | 45 | 24 | 2nd-gen Bangladeshi | |||||

| Ghai et al. (2012)29 | White American | USA | 50 425 | 100 | ≈ 58 | American | I | 1st/≥ 2nd |

| 579 | 100 | ≈ 58 | South Asian | |||||

| Sachan & Samuel (1999)23,a | White American | USA | 23 | 0 | 29–69 | American | I | – |

| Indians living in South Asia | India | 31 | 0 | 26–59 | South Asians in USA | |||

| 27 | 0 | 28–69 | South Asians in South Asia | |||||

| Pomerleau et al. (1997)24 | Canadian | Canada | 29 458 | 49 | 41 | Canadian | I | 1st |

| 163 | – | – | Indian | |||||

| Pomerleau et al. (1998)30 | Canadian | Canada | 29 458 | 49 | 41 | Canadian | I | 1st |

| 163 | – | – | Indian | |||||

| Pomerleau et al. (1998)31 | Canadian | Canada | 29 458 | 49 | 41 | Canadian | I | 1st |

| 163 | – | – | Indian | |||||

| Parackal et al. (2015)32,b | NZ European/other | NZ | 2728 | 47 | ≈ 46 | New Zealander | I, P, B, SL, N, A | – |

| Western residence | NZ | 130 | 57 | ≈ 39 | South Asian | |||

| < 10 y | 74 | 50 | – | |||||

| ≥ 10 y (ref) | 54 | 52 | – | |||||

| Bharmal et al. (2015)33,b | Western residence | USA | 1169 | 58 | 40 | South Asian | I, P, B, SL, N, BH | 1st |

| 0 to < 5 y residence | 144 | – | – | |||||

| 5 to < 10 y residence | 217 | – | – | |||||

| 10 to < 15 y residence | 219 | – | – | |||||

| ≥ 15 y residence (ref) | 589 | – | – | |||||

| Talegawkar et al. (2016)21 | Western residence | USA | 874 | 53 | 56 | South Asian | I, P, B, SL, N | – |

| 1st tertile | 298 | 52 | 51 | |||||

| 2nd tertile | 293 | 51 | 54 | |||||

| 3rd tertile (ref) | 283 | 56 | 62 | |||||

| Wandel et al. (2008)34 | Western residence | Norway | 629 | 58 | 42 | South Asian | P, SL | 1st |

| ≤ 10 y residence (ref) | – | – | – | |||||

| > 10 y residence | – | – | – | |||||

| Sarwar et al. (2015)35,b | Western residence | USA | 398 | – | ≈ 39 | South Asian | I, P, B, SL38 | 1st/≥ 2nd |

| < 15 y residence (ref) | – | – | – | |||||

| > 15 y residence | – | – | – | |||||

| Lesser et al. (2014)36 | Western residence | Canada | 121 | ≈ 52 | ≈ 48 | South Asian | I, P, B, SL, N | 1st |

| ≤ 13.8 y (ref) | 32 | 62 | 46 | |||||

| 13.9–21.1 y | 32 | 59 | 44 | |||||

| 21.2–32.1 y | 32 | 39 | 49 | |||||

| ≥ 32.2 y | 25 | 47 | 53 | |||||

| Chiu et al. (2012)37 | Western residence | Canada | 3364 | 52 | – | South Asian | I, P, B, SL | – |

| < 15 y residence (ref) | 1791 | 50 | – | |||||

| ≥ 15 y residence | 1573 | 53 | – | |||||

| Becerra et al. (2014)38,b | Western residence | USA | 1352 | 56 | 38 | South Asian | I, P, B, SL | 1st/2nd/≥ 3rd |

| 1st gen (ref) | 1125 | – | – | |||||

| 2nd gen | 208 | – | – | |||||

| 3rd gen | 17 | – | – |

Abbreviations and symbols: A, Afghanistan; B, Bangladesh; BH, Bhutan; gen, generation; I, India; N, Nepal; NZ, New Zealand; P, Pakistan; ref, referent group; SL, Sri Lanka; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; –, information not provided or available; ≈, approximations based on weighted averages of frequencies within given sexes or age ranges.

aOnly age ranges were provided for each group of interest.

bSample characteristics based on survey-weighted frequencies.

Table 2.

Diet assessment methods used in the 19 studies of diet in South Asian immigrants that met criteria for relevance and statistical analysis

| Reference | Diet assessment measure | Development of assessment measure | Validity of assessment measure | Languages offered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sevak et al. (1994)27,a | 7-d weighed food diary | Not reported | Not examined | – |

| Anderson et al. (2005)26 | 7-d weighed food diary | Not reported | Not examined | – |

| Sachan & Samuel (1999)23,a | 4-d food diary | Modified original diary developed for pregnant and postpartum adolescents | Not examined | – |

| Donin et al. (2010)17 | Single 24-h recall | Followed recommendations of Nordic Cooperation Group of Dietary Researchers and included elements of the USDA multiple-pass method. Adapted for children.39 | Not examined | Verbal interview in English |

| Parackal et al. (2015)32,a | Single 24-h recall | Closed list of foods/beverages based on those regularly consumed in New Zealand40 | Not examined | Verbal assistance in English, Maori, Samoan, Tongan, Chinese, Korean, Hindi, and Punjabi40 |

| Talegawkar et al. (2016)21 | Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic groups semiquantitative FFQ | Modified FFQ from Canadian Study of Diet, Lifestyle, and Health using multiple 24-h recalls or single 24-h recalls + 4-d diet records from 29 South Asian immigrants41 | Validated against 7-d food record in 58 South Asian immigrants. Pearson r for macronutrients ranged from 0.45 (grams of protein) to 0.64 (grams of saturated fat)41 | Written FFQ in English, Hindi, and Urdu42 |

| Wandel et al. (2008)34 | Modified Oslo Health Study (HUBRO) FFQ and questionnaire on dietary change | Pilot-tested HUBRO FFQ in a group of 130 Pakistani immigrants Questionnaire on dietary change was then created on the basis of the significance of foods in terms of health benefits and adoption of Norwegian food habits | Original HUBRO FFQ validated for ethnic Norwegians43 Details on sample size, comparison method, or statistical results of the validation study were not reported Validity of questionnaire on dietary change not examined | Written FFQ in English and Norwegian,44 plus verbal assistance in English, Norwegian, Urdu, Punjabi, and Tamil |

| Simmons & Williams (1997)25 | FFQ | Not reported | Not examined | Written FFQ in native language, plus verbal assistance in native language |

| Ghai et al. (2012)29 | Women’s Health Initiative semiquantitative FFQ | Based on FFQs from the Women’s Health Trial, Women's Health Trial Vanguard Study and Full-Scale Studies, Working Well Trial, and the Women’s Health Trial Feasibility Study in Minority Populations | Validated for macro- and micronutrient intake against 4-d food records and 4 d of 24-h recalls in 113 white, African American, and other women in the USA. Pearson r for macronutrients ranged from 0.36 (grams of protein) to 0.62 (percent total fat)45 | – |

| Pomerleau et al. (1997, 1998)24,30,31 | Semiquantitative FFQ | Developed for the Ontario Health Study, with a focus on fat, fiber, and calcium46 | Validated against 4-d weighed food records in 147 Canadians. Spearman r for macronutrients ranged from 0.323 (percent protein) to 0.539 (total grams of fat)46 | Written FFQ in English, French, Italian, Chinese, and Portuguese |

| Lesser et al. (2014)36 | Section of comprehensive Multi-Cultural Community Health Assessment Trial questionnaire | Not reported | Not examined | Written questionnaire in English, Punjabi, and Chinese47 |

| Smith et al. (2012)28 | Section of Health Survey for England (1998, 1999, 2003, 2004). Only white comparison population drawn from 1998 and 2003 | Not reported | Not examined | Written questionnaire (1999, 2004) and interview (2004) in English, Gujarati, Hindi, Punjabi, Urdu, Bengali, Cantonese, and Mandarin48,49 |

| Bharmal et al. (2015),33 Sarwar et al. (2015),35 and Becerra et al. (2014)38 | Section of California Health Interview Survey questionnaire (2005, 2007, 2009, 2011) | Developed so that total questionnaire would not exceed 30 min and would cover a wide variety of health-related research topics. Pretested and pilot-tested the English language version each year50–53 | Not examined | Written questionnaire in English, Spanish, Cantonese, Mandarin, Korean, and Vietnamese50–53 |

| Chiu et al. (2012)37 | Section of Canadian Community Health Survey (2001, 2003, 2005, 2007) | Developed in collaboration with Statistics Canada, other departments, and academic fields. Conducted 2 field tests each year54–57 | Not examined | Written questionnaire in 25 languages, including Punjabi, Tamil, Hindi, and Urdu54–57 |

| Stone et al. (2007)22 | Questionnaire of previous day’s intake | Modified original questionnaire developed to track changes in diet among schoolchildren58 | Validated original questionnaire against 3-d food diaries in 96 adolescents of unknown ethnicity in the UK. Not valid for assessing intake of fibrous foods, positive marker foods, or foods containing altered fat or altered sugar59 | – |

Abbreviations and symbols: FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; USDA, US Department of Agriculture; — , information not provided or not available.

In any study of diet, it is important that strong assessment methodology be used, and for the topic of the present review it was also crucial that the diet data collection method be sensitive to cultural differences in food consumption. Food diaries collect dietary intake data by having participants write down all foods consumed over a prespecified period of time.60 There are no restrictions on the types of foods to be recorded,60 and thus the method has high utility across cultures. Three studies collected dietary information using either a 7-day26,27 or 4-day23 food diary. The studies that collected data for 7 days required participants to weigh or measure the foods and beverages consumed,26,27 and the remaining study instructed participants to estimate or measure the amounts consumed.23 Information on the development and validation of the food diaries was generally not provided. Sachan and Samuel23 adapted (in an unspecified manner) a food diary previously developed for pregnant and postpartum adolescents,61 but no information on validation was given.

Although food diaries are an established method of diet assessment,62 the accuracy of information obtained using either a weighed or an estimated food diary in a population of immigrants may be limited by literacy and familiarity with measurement tools and systems.60 Anderson et al.,26 Sevak et al.,27 and Sachan and Samuel23 all addressed this concern by providing participants with written or oral instructions on how to use the diaries and the household measures and food scales, as appropriate. These 3 studies also incorporated follow-up visits or calls (during the recording period or after completion of diet assessment to address participant questions, clarify unclear records, and probe for potentially forgotten foods. Given these measures, all 3 studies were retained in the final summary.

Similar to the food diary, the 24-hour recall usually does not limit the types of foods reported.60 This assessment is usually administered by an interviewer, with the interviewer leading the participant through an oral report of all foods eaten in a specified 24-hour period.60 Two studies included in the present review used a single 24-hour recall to assess dietary intake.17,32 Although multiple days of recall are strongly preferred, the use of a single 24-hour recall is appropriate for the purpose of describing average dietary intake at the group level.60 Donin et al.17 used an interviewer-administered 24-hour recall (that was adapted for children39) and obtained detailed information on ethnic-specific foods. Interviews were conducted in English, which was the language taught in school to all children who participated in the study.17 Parackal et al.32 used a computer-assisted 24-hour recall (with verbal assistance in South Asian languages, including Hindi and Punjabi40) with a closed list of foods. This list was generated using foods frequently consumed in New Zealand40 and could have excluded foods regularly consumed by South Asian immigrants. For that reason, the study of Parackal et al. was excluded,32 but the study of Donin et al. was retained.17

Seven studies collected dietary data using an FFQ, 5 of which used semiquantitative FFQs21,24,29–31 and 2 of which measured intake frequency without indicating the amount consumed.25,34 Because FFQs rely on a closed list of foods that may not capture items usually consumed by South Asian immigrants, the quality of studies that use them depends on whether the authors created, adapted, or validated their FFQ for use in a sample of South Asian immigrants.60,63,64 Talegawkar et al.21 and Wandel et al.34 both adapted existing FFQs to ensure that they appropriately captured the diet of South Asians. They pilot tested previously developed FFQs using South Asians living in Canada21 or Norway,34 adding and removing items as needed. Talegawkar et al.21 translated the modified FFQ into 2 South Asian languages (Hindi or Urdu),42 while Wandel et al.34 provided the modified written FFQ in either English or Norwegian,44 with verbal assistance provided in English, Norwegian, Urdu, Punjabi, or Tamil. The original questionnaires were validated for the general population65 or for natives of each country,43 but only the FFQ used by Talegawkar et al.21 was validated following alteration.41 Nevertheless, both the Wandel et al.34 and the Talegawkar et al.21 studies were retained in the final summary.

The other 5 articles that measured diet using an FFQ were not included in the final summary of results.24,25,29–31 Simmons and Williams25 administered the FFQ in participants’ native language, but they did not provide information on the development or validation of the measure. Thus, it was unclear whether the FFQ was appropriate for use in a population of South Asian immigrants. Similarly, Ghai et al.29 and Pomerleau et al.24,30,31 did not develop or validate their FFQs using a South Asian population or provide the questionnaires in languages commonly spoken by South Asians.45,46

Studies that used instruments that captured focused aspects of diet, rather than overall diet, or that asked about diet-related behaviors such as food preparation were also included in this review. In this context, the necessity for inclusion of culturally appropriate foods is less imperative if assessment of all foods consumed or all foods in a category (eg, fruits) was not the goal. Wandel et al.34 and Lesser et al.36 used a list of questions with the purpose of assessing changes in intakes of specific foods, food categories, or food habits since immigration, rather than changes in overall diet.44,66 Both studies offered the questionnaire in Punjabi,47 with Wandel et al.34 providing additional verbal assistance in other South Asian languages. Lesser et al.36 did not adapt the instrument for use in South Asian populations, but Wandel et al.34 modified their questionnaire as previously mentioned, on the basis of a pilot study among South Asians. Both studies were retained in this review, but the discussion of the findings of Lesser et al.36 will be limited to those related to food preparation, given that the authors assessed consumption of entire food categories without adapting the instrument for South Asians.

Smith et al.28 administered an eating habits questionnaire in 5 South Asian languages (Gujarati, Hindi, Punjabi, Urdu, and Bengali) in 1999 and 2004.48,49 The 2004 questionnaire was shorter than the 1999 questionnaire and was supplemented with interviewer-administered questions about the previous day’s fruit and vegetable consumption.48,49 The process used for the development of the eating habits questionnaire was not reported, but prompts and examples included ethnic-specific foods commonly consumed by South Asian populations.48,49 Therefore, this study was retained in the summary.

Five other studies that administered questionnaires were not included in the summary of results.22,33,35,37,38 Three of these (Bharmal et al.,33 Sarwar et al.,35 and Becerra et al.38) assessed specific food categories using selected questions from the California Health Interview Survey, but the questionnaire was not developed or validated in South Asians and was not provided in languages commonly spoken by South Asians.50–53 Chiu et al.37 used selected questions from the Canadian Community Health Survey, intending to measure usual fruit and vegetable intake. Although the questionnaire was translated into 25 languages, it was not adapted to or validated in South Asians.54–57 Because these 4 studies aimed to assess intake within entire food/beverage categories without adapting the questionnaire for South Asians, they were excluded. A study by Stone et al.22 was also excluded because the food intake questionnaire used was not developed or modified for South Asian populations and was found to have poor validity in 4 of 7 categories of foods queried.59

Of the 19 studies reviewed, only 1 conducted in a child-only sample used a diet assessment measure considered appropriate for use in South Asian immigrant populations.17 Therefore, the summary was restricted to the remaining 7 studies, all of which were conducted in samples aged 20 years and older, with the exception of the study by Smith et al.,28 which included participants as young as 16 years of age.

SUMMARY OF THE 7 STUDIES THAT USED APPROPRIATE STATISTICAL ANALYSES AND DIET ASSESSMENT METHODS

Seven of the 19 articles reviewed used diet assessment methods deemed sufficient to meet minimum standards.21,23,26–28,34,36 Details on the type of data collected, the approach to analysis, and the findings for the 7 studies that met the criteria for statistical analysis and diet assessment are outlined in Table 3,21,23,26–28,34,36,44,48,49,65–68 according to the groups compared: South Asian immigrants vs Westerners, long-term vs recent South Asian immigrants, and South Asian immigrants living in Western countries vs South Asians living in South Asia.

Table 3 .

Results from the 7 studies that met criteria for relevance, statistical analysis, and diet methodology

| Comparison/reference | Data collected | Method of analysis | Diet outcomes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total energy | Carb | Protein | Fat | Other | |||

| South Asian immigrants vs Westerners: examinations of nutrient intake | |||||||

| Sevak et al. (1994)27,a | 7-d weighed food diaries. Weights of ingredients and cooked food; food description, and portion sizes for dining out | Least-squares regression adjusted for age. Used percent energy for macronutrients | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | Total ↓ | – |

| SFA NS | |||||||

| MUFA ↓ | |||||||

| PUFA ↑ | |||||||

| Anderson et al. (2005)26,b,c | 7-d weighed food diaries. Weights of cooked food and leftovers; recipe details; menu items when dining out; salt; and dietary supplement use | Multivariate analysis of variance adjusted for age and number of children in household. Used grams and percent energy for macronutrients | ↑, 1st gen | NS, 1st/2nd gen (g and %) | ↓, 1st/2nd gen (%) | Total ↑, 1st gen | ↑ Vitamin E density, 1st/2nd gen |

| SFA – | ↓ Sodium density, 1st/2nd gen | ||||||

| MUFA ↓, 2nd gen (%) | |||||||

| PUFA – | ↓ Potassium density, 1st gen | ||||||

| Sachan & Samuel (1999)23,a,b,c | 4-d food diaries (3 weekdays, 1 weekend day). Details not reported | Generalized linear models adjusted for age, education, and/or total energy. Used grams for macronutrients | ↓ | – | – | Total – | ↓ Vitamin A |

| SFA ↓ | ↓ Vitamin E | ||||||

| MUFA ↓ | |||||||

| PUFA ↓ | |||||||

| South Asian immigrants vs Westerners: examinations of food group intake or dietary habits | |||||||

| Smith et al. (2012)28 | Questionnaire of usual eating habits (frequency, type, and amount of foods as well as added fat and salt use); included 20–24 items in 1998–19994,8,67 and 13 items in 2003–2004.49,68 Previous day’s fruit and vegetable intake also included (2003–2004) | Logistic regression adjusted for age and sex | – | – | – | – | ↓ ≥ 6 times/wk consumption of crisps (chips), chocolate, and biscuits (cookies) |

| ↓ < 1 portion/d fruit consumption (except 2nd-gen Indians) | |||||||

| ↓ < 1 portion/d vegetable consumption | |||||||

| ↑ ≥ 3 times/wk fried food consumption (1st-/2nd-gen Indians and 1st-gen Pakistanis) | |||||||

| Long-term vs recent South Asian immigrants: examinations of nutrient intake | |||||||

| Talegawkar et al. (2016)21,c,d | FFQ containing 102 items from the Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic groups and 61 unique items that were added after pilot testing. Open-ended frequency responses about intake during previous year,65 with 3 serving sizes per item | Generalized linear models adjusted for age, sex, and total energy. Dunnett’s adjustment used for pairwise comparisons of adjusted means. Used grams and percent for macronutrients, except for subtypes of fat (used grams only) | Trends | ||||

| ↓ | ↓ (g and %) | ↓ (g and %) | Total ↑ (g and %) | Folate ↓ | |||

| Potassium ↓ | |||||||

| SFA ↑ | |||||||

| MUFA – | |||||||

| PUFA ↑ | |||||||

| Pairwise | |||||||

| ↓, 1st tertile | ↓, 1st/2nd tertile (g, 1st/2nd; % 1st) | ↓, 1st tertile (g and %) | Total ↑, 1st/2nd tertile (g and %) | Folate ↓, 1st/2nd tertile | |||

| SFA NS | Potassium ↓, 1st/2nd tertile | ||||||

| MUFA – | Vitamin C ↓, 2nd tertile Vitamin E ↓, 2nd tertile | ||||||

| PUFA NS | |||||||

| Long-term vs recent South Asian immigrants: examinations of food group intake or dietary habits | |||||||

| Lesser et al. (2014)36,d | Questionnaire containing 26 items on changes in food preparation, consumption, and nutrition knowledge/awareness since immigration.66 Used 5-point Likert scale of decreased to increased change | Spearman correlation to identify dietary variables associated with length of residence; used these 4 items as dependent variables in ordinal models adjusted for age, sex, education, and BMI | – | – | – | – | ↑ Stir frying/barbecuing (13.9–21.1 y since immigration), baking or grilling (13.9–21.1 y since immigration), and microwaving (21.1–32.1 y since immigration) |

| Wandel et al. (2008)34 | Questionnaire containing 11 items on dietary change with 3 possible responses: increase, decrease, or no change; 43 items retained from HUBRO FFQ plus 12 items that were added or reworded. All items in FFQ asked about usual intake instead of intake during defined time period44 | Logistic regression for changes in intake from 4 primary sources of fat and adherence to 3 food-use patterns adjusted for age, sex, country of origin, work status, language, and Norwegian integration index score | – | – | – | – | ↑ Consumption of meat |

| NS use of oil, butter, and margarine | |||||||

| NS adherence to patterns of foods rich in fat, foods rich in sugar, and mostly Norwegian diet | |||||||

| South Asian immigrants vs South Asians living in South Asia | |||||||

| Sachan & Samuel (1999)23,a,b,c | 4-d food diaries (3 weekdays, 1 weekend day). Details not reported | Generalized linear models adjusted for age, education, and/or total energy Used grams for macronutrients | ↓ | – | – | Total – | Vitamin A ↓ |

| SFA NS | |||||||

| MUFA ↑ | |||||||

| PUFA ↑ | |||||||

Abbreviations and symbols: BMI, body mass index; Carb, carbohydrate; gen, generation; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acid; NS, not significant; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; SFA, saturated fatty acid; –, information not provided or available; ↓, lower intake among South Asian immigrants vs Westerners, long-term vs recent South Asian immigrants, South Asian immigrants vs South Asians living in South Asia; ↑, higher intake among South Asian immigrants vs Westerners, long-term vs recent South Asian immigrants, South Asian immigrants vs South Asians living in South Asia;

aAdditional diet assessment measures used, but results from those measures were either not reported (Sevak et al. [1994]27) or were examined using only crude analyses (Sachan & Samuel [1999]23).

bSummarized findings limited to those adjusted for both age and sex (Sachan & Samuel [1999]23) or to those clearly delineated as significant in the text or tables in the original manuscript (Anderson et al. [2005]26).

cOnly significant findings for micronutrients are shown.

When some results in a publication met the criteria and others did not, the summary was restricted to compliant results. For example, summarized results were limited to comparisons of total energy intake and subtypes of fat for Sachan and Samuel23 and to comparisons of nutrient intake for Talegawkar et al.,21 since other analyses in these studies were not adjusted for both age and sex. Similarly, findings for Anderson et al.26 were limited to pairwise comparisons that were clearly delineated as significant or nonsignificant in the text. In the sections below, intakes described in percentages represent intakes as a percentage of total energy21,23,27 or food energy.26 Results were considered statistically significant if differences met the criterion of P<0.05.

Studies comparing South Asian immigrant populations with Western populations

Nutrient intake.

Four articles showed dietary comparisons between South Asian immigrants and Westerners (Table 3).23,26–28 Three of these provided comparisons of total energy and macronutrient intakes23,26,27 and found that intakes of protein26,27 and monounsaturated fat23,26,27 were significantly lower in South Asian immigrants than in Westerners. Protein intake for South Asian immigrants compared with Europeans was 13.7% vs 15.1%27 and 13.1% (first-generation immigrants) and 13.8% (second-generation immigrants) vs 15.1%.26 Similarly, monounsaturated fat consumption for South Asian immigrants compared with Westerners was 11.9% vs 14.7%,27 12.4% (second-generation immigrants) vs 13.7%,26 and 13.6 g vs 18.6 g.23

Although results for intakes of protein and monounsaturated fat were consistent, findings for intakes of total energy,23,26,27 carbohydrate,26,27 total fat,26,27 saturated fat,23,27 and polyunsaturated fat23,27 were mixed across studies. Two studies found that total energy intake was lower in South Asian immigrants than in Westerners.23,27 Sevak et al.27 reported intakes of 9.5 MJ (2269 kcal) vs 10.8 MJ (2580 kcal) in their sample of male Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi immigrants vs Europeans, and Sachan and Samuel23 reported intakes of 1732 kcal vs 1844 kcal in their sample of female Indian immigrants vs white Americans. The one study that reported a greater energy intake for South Asian immigrants than for Westerners, ie, Anderson et al.,26 also limited the sample to females and, as with Sevak et al.,27 compared Indians, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi immigrants with Europeans.26 However, it differed from the aforementioned studies in that it excluded calories from beverages in the calculation of total energy intake and restricted the sample to first- and second-generation immigrants, finding that first-generation immigrants had a significantly higher energy intake compared with Europeans, at 7950 kJ (1900 kcal) vs 6975 kJ (1667 kcal).26

Carbohydrate,26,27 total fat,26,27 saturated fat,23,27 and polyunsaturated fat23,27 intakes were examined in 2 different sets of studies. Only Sevak et al.27 and Sachan and Samuel23 reported significant differences in intakes of carbohydrate (46.4% vs 40.9%)27 and saturated fat (15 g vs 17 g)23 for South Asian immigrants compared with Westerners, respectively. Anderson et al.26 and Sevak et al.27 reported significant yet opposite differences in total fat intake of 42.4% (first-generation immigrants) vs 39.1%26 and 36.5% vs 39.2%27 for comparisons of South Asian immigrants with Europeans, respectively. Similarly, results for trends in polyunsaturated fat intake contradicted, with consumption being 8.2% vs 7.0%27 and 7.7 g vs 10.7 g23 for South Asian immigrants compared with Westerners, respectively.

Examination of micronutrients in these 3 studies showed that South Asian immigrants tended to have lower intakes of micronutrients than Westerners, although results were mixed for vitamin E.23,26 Anderson et al.26 reported more vitamin-E-dense diets among first- and second-generation South Asian immigrant adults than among Europeans (0.9 mg/1000 kJ and 0.8 mg/1000 kJ vs 0.6 mg/1000 kJ, respectively), while Sachan and Samuel23 reported lower vitamin E intake among South Asian immigrants than among white Americans (2.6 mg vs 4.4 mg). The specific micronutrients that were lower among South Asian immigrants were potassium (280 mg/1000 kJ [first-generation immigrants] vs 360 mg/1000 kJ), sodium (315 mg/1000 kJ [first-generation immigrants] and 320 mg/1000 kJ [second-generation immigrants] vs 385 mg/1000 kJ),26 and vitamin A (618 retinol equivalents [RE] vs 1370 RE).23

Food group intake or dietary habits.

Smith et al.28 compared food groups in the diets of South Asian immigrants and Westerners. They examined frequency of intake and found that, compared with white Europeans, both first- and second-generation South Asian immigrants consumed snacks less frequently and fried and micronutrient-rich foods (ie, fruits and vegetables) more frequently.

Studies comparing South Asian immigrants by time since immigration

Nutrient intake.

Talegawkar et al.21 examined Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan, and Nepali immigrants living in the United States and found that length of residence was inversely associated with intakes of total energy, carbohydrate, protein, folate, and potassium and directly associated with intakes of total fat, saturated fat, and polyunsaturated fat. Significant pairwise comparisons tended to be limited to recent vs long-term immigrants, specifically for intakes of total energy (7373 kJ [1762 kcal] vs 6734 kJ [1609 kcal], respectively), carbohydrate (57.4% vs 55.0% or 251 g vs 240 g, respectively), and protein (14.9% vs 14.4% or 62.6 g vs 61.0 g, respectively). For total fat and the aforementioned micronutrients, however, both recent and semi-recent immigrants had significantly different intakes compared with long-term immigrants: 28.3% and 29.1% vs 30.3% or 53.1 g and 54.6 g vs 56.7 g for total fat, respectively; 416 µg and 410 µg vs 388 µg for folate, respectively; and 3664 mg and 3690 mg vs 3554 mg for potassium, respectively.

Food group intake or dietary habits.

Lesser et al.36 and Wandel et al.34 analyzed food intake and food preparation methods among first-generation immigrants, with Lesser et al.36 examining immigrants from the same countries described by Talegawkar et al.,21 and Wandel et al. narrowing the focus to immigrants from 2 of those countries (Pakistan and Sri Lanka). Lesser et al.36 found that increasing duration of residence in a Western country was associated with an increased odds of stir frying or barbecuing (odds ratio [OR] = 3.71, P = 0.024), baking or grilling (OR = 6.36, P = 0.002), and microwaving (OR = 2.75, P = 0.047). Wandel et al.34 reported that increasing duration of residence in a Western country was associated only with an increased odds of meat consumption (OR = 1.6, P < 0.05). Differences in consumption of butter, margarine, and oil and adherence to select food patterns were not significant.34

Studies comparing South Asian immigrants with South Asians living in South Asia

Of the 7 selected articles, only 1 reported a quantitative analysis comparing South Asians living in a Western country to South Asians living in South Asia (Table 3).23 Sachan and Samuel23 found that Asian Indians in the United States had significantly lower intakes of total energy (1732 kcal vs 1976 kcal) and vitamin A (618 RE vs 1191 RE) compared with Indians in India and a higher intake of monounsaturated fats (13.6 g vs 9.2 g) and polyunsaturated fats (7.7 g vs 4.6 g) compared with Indians in India. There was no difference in saturated fat intake between the 2 groups.

CONCLUSION

This critical narrative review of the literature identified 7 studies in adult populations that used sufficiently adjusted statistical analyses and culturally appropriate diet assessment measures to analyze dietary intake among South Asians following immigration to a Western country.21,23,26–28,34,36 Many results conflicted across studies, but there were some consistencies. Three studies showed that monounsaturated fat intake was lower in South Asian immigrants than in Westerners.23,26,27 One study showed that monounsaturated fat intake was higher in South Asian immigrants than in South Asians living in South Asia.23 These findings suggest a continuum, with monounsaturated fat intake being lowest in South Asians living in South Asia, highest in Westerners, and intermediate in South Asians living in a Western country. However, Anderson et al.26 found that second-generation, but not first-generation, immigrants had a lower monounsaturated fat intake compared with Westerners, which is not consistent with a hypothesized time trend of increasing monounsaturated fat intake with greater exposure to a Western culture. Findings for protein were also relatively consistent across studies, with 2 studies showing that protein intake was lower in South Asian immigrants than in Westerners.26,27 Talegawkar et al.21 reported that increased duration of residence was associated with decreased protein intake, but Anderson et al.26 did not observe a similar decline across generations of immigrants.

Findings for total energy intake were mixed for comparisons of South Asian immigrants and Westerners, and these differences might be attributable to time since immigration. Talegawkar et al.21 found that total energy intake decreased as duration of residence in a Western country increased, and thus total energy intake may continue to decrease across immigrant generations. This could explain why Anderson et al.26 observed that first-generation South Asian immigrants had higher energy intakes than Europeans, while the 2 studies with samples of mixed-generation immigrants found that South Asian immigrants had lower energy intakes than Westerners.23,27

Time since immigration does not appear to explain the mixed findings for carbohydrate, total fat, saturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, and micronutrient intakes, but information on the country of origin may help explain the discrepancies in findings. Two of the 7 studies included in this review presented findings by or adjusted for South Asian immigrants’ country of origin and found significant differences in dietary intake and habits.28,34 One of the 4 studies examining macro- and micronutrient intakes limited the sample to Asian Indians only.23 The remaining studies used samples with individuals from multiple South Asian countries, which may have resulted in the mixed findings.

It is also possible that other markers of integration into Western culture, besides time since immigration (eg, language fluency or social affiliation), may help explain the mixed findings for the aforementioned macro- and micronutrients. Only 1 of the 7 included studies examined other markers, but it did not assess nutrient intake.34 The authors found that language fluency and degree of cultural integration (examined using an unvalidated 9-point index of integration based on whether immigrants read the host country’s [Norway’s] newspapers, socialized with ethnic Norwegians, and participated in organizations in Norway) were significantly associated with food preparation methods and food intake following immigration to a Western country.34

An important strength of this critical review was the exclusion of studies on the basis of detailed evaluation of the study design, statistical analyses, and diet methodology. This process resulted in the exclusion of numerous papers, but the criteria applied were considered crucial for the identification of useful information. The intent was to highlight studies that were of high quality and to increase the likelihood that they accurately captured and compared diets of South Asian immigrants. A weakness is that a critical narrative review, rather than a formal systematic review, was conducted. The databases searched may have missed some relevant articles, and it is always possible some articles may have been misclassified.

Given the large number of South Asian immigrants to Western countries and the relevance of diet to many of the health problems they face, it is important that future studies address the mixed findings and gaps in knowledge uncovered here. New research needs to use well-defined samples, study designs, and analyses that control for confounding by age and sex, and dietary measures that are developed and validated for South Asian immigrants. In addition, more information is needed on variables that have previously been shown to influence diet following immigration. Variables such as duration of residence, immigrant generation, country of origin, socioeconomic status, language, religion, and food restrictions would aid the interpretation and understanding of diet-related choices.9,10,69 Future research should aim to examine the intake of food groups as well as the intake of macro- and micronutrients to add context to nutrient intake. Furthermore, future research should examine other markers of integration into Western culture aside from time since immigration and should include South Asians living in South Asia as a comparison population, given the relative lack of information on this contrast. Such research will more fully characterize the dietary intake and habits of South Asian immigrants in Western countries and thus identify specific dietary targets for obesity interventions in South Asian immigrants.

Acknowledgments

Funding/support. No external funds supported this work.

Declaration of interest. The authors have no relevant interests to declare.

References

- 1. Population Reference Bureau. 2015 World Population Data Sheet. http://www.prb.org/pdf15/2015-world-population-data-sheet_eng.pdf. Published August 2015. Accessed July 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. UK Office for National Statistics. Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales: 2011. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/ethnicity/articles/ethnicityandnationalidentityinenglandandwales/2012-12-11#background-notes. Published December 2012. Accessed July 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Statistics Canada. Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity in Canada: National Household Survey, 2011. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.cfm#a3. Published 2013. Accessed July 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO et al. The Asian Population: 2010. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf. Issued March 2012. Accessed July 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Statistics New Zealand. 2013 Census QuickStats about Culture and Identity. http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/quickstats-culture-identity/asian.aspx. Published April 15, 2014. Accessed July 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. UK Office for National Statistics. International Migrants in England and Wales: 2011. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/articles/internationalmigrantsinenglandandwales/2012-12-11. Published December 11, 2012. Accessed July 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. US Census Bureau, American Community Survey. 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Table B05006. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_14_1YR_B05006&prodType=table. Revised September 4, 2015. Accessed August 7, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gilbert PA, Khokhar S. Changing dietary habits of ethnic groups in Europe and implications for health. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holmboe-Ottesen G, Wandel M. Changes in dietary habits after migration and consequences for health: a focus on South Asians in Europe. Food Nutr Res. 2012;56 doi:10.3402/fnr.v56i0.18891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hauck K, Hollingsworth B, Morgan L. BMI differences in 1st and 2nd generation immigrants of Asian and European origin to Australia. Health Place. 2011;17:78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Staimez LR, Weber MB, Narayan KM et al. A systematic review of overweight, obesity, and type 2 diabetes among Asian American subgroups. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2013;9(4):312–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anand SS, Yusuf S, Vuksan V et al. Differences in risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease between ethnic groups in Canada: the Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic groups (SHARE). Lancet. 2000;356:279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gadgil MD, Anderson CA, Kandula NR et al. Dietary patterns are associated with metabolic risk factors in South Asians living in the United States. J Nutr. 2015;145:1211–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Landman J, Cruickshank JK. A review of ethnicity, health and nutrition-related diseases in relation to migration in the United Kingdom. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4:647–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26:91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Donin AS, Nightingale CM, Owen CG et al. Nutritional composition of the diets of South Asian, black African-Caribbean and white European children in the United Kingdom: the Child Heart and Health Study in England (CHASE). Br J Nutr. 2010;104:276–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Donin AS, Nightingale CM, Owen CG et al. Ethnic differences in blood lipids and dietary intake between UK children of black African, black Caribbean, South Asian, and white European origin: the Child Heart and Health Study in England (CHASE). Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:776–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Donin AS, Nightingale CM, Owen CG et al. Dietary energy intake is associated with type 2 diabetes risk markers in children. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:116–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Donin AS, Dent JE, Nightingale CM et al. Fruit, vegetable and vitamin C intakes and plasma vitamin C: cross-sectional associations with insulin resistance and glycaemia in 9–10 year-old children. Diabet Med. 2016;33:307–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Talegawkar SA, Kandula NR, Gadgil MD et al. Dietary intakes among South Asian adults differ by length of residence in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19:348–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stone MA, Bankart J, Sinfield P et al. Dietary habits of young people attending secondary schools serving a multiethnic, inner-city community in the UK. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:115–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sachan DS, Samuel P. Comparison of dietary profiles of Caucasians and Asian Indian women in the USA and Asian Indian women in India. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 1999;26:161–171. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pomerleau J, Ostbye T, Bright-See E. Food intake of immigrants and non-immigrants in Ontario: food group comparison with the recommendations of the 1992 Canada’s Food Guide to Healthy Eating. J Can Diet Assoc. 1997;58:68–76. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Simmons D, Williams R. Dietary practices among Europeans and different South Asian groups in Coventry. Br J Nutr. 1997;78:5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson AS, Bush H, Lean M et al. Evolution of atherogenic diets in South Asian and Italian women after migration to a higher risk region. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2005;181:33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sevak L, McKeigue PM, Marmot MG. Relationship of hyperinsulinemia to dietary intake in south Asian and European men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:1069–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith NR, Kelly YJ, Nazroo JY. The effects of acculturation on obesity rates in ethnic minorities in England: evidence from the Health Survey for England. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22:508–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ghai NR, Jacobsen SJ, Van Den Eeden SK et al. A comparison of lifestyle and behavioral cardiovascular disease risk factors between Asian Indian and White Non-Hispanic Men. Ethn Dis. 2012;22:168–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pomerleau J, Ostbye T, Bright-See E. Place of birth and dietary intake in Ontario. I. Energy, fat, cholesterol, carbohydrate, fiber, and alcohol. Prev Med. 1998;27:32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pomerleau J, Ostbye T, Bright-See E. Place of birth and dietary intake in Ontario. II. Protein and selected micronutrients. Prev Med. 1998;27:41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parackal SM, Smith C, Parnell WR. A profile of New Zealand “Asian” participants of the 2008/09 Adult National Nutrition Survey: focus on dietary habits, nutrient intakes and health outcomes. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18:893–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bharmal N, Kaplan RM, Shapiro MF et al. The association of duration of residence in the United States with cardiovascular disease risk factors among South Asian immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17:781–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wandel M, Råberg M, Kumar B et al. Changes in food habits after migration among South Asians settled in Oslo: the effect of demographic, socio-economic and integration factors. Appetite. 2008;50:376–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sarwar E, Arias D, Becerra BJ et al. Sociodemographic correlates of dietary practices among Asian-Americans: results from the California Health Interview Survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2:494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lesser IA, Gasevic D, Lear SA. The association between acculturation and dietary patterns of South Asian immigrants. PloS One. 2014;9:e88495 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chiu M, Austin PC, Manuel DG et al. Cardiovascular risk factor profiles of recent immigrants vs long-term residents of Ontario: a multi-ethnic study. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28(1):20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Becerra MB, Herring P, Marshak HH et al. Generational differences in fast food intake among South-Asian Americans: results from a population-based survey. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E211 doi:10.5888/pcd11.140351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Frank GC, Berenson GS, Schilling PE et al. Adapting the 24-hr. recall for epidemiologic studies of school children. J Am Diet Assoc. 1977;71:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. University of Otago and Ministry of Health. Methodology Report for the 2008/09 New Zealand Adult Nutrition Survey. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kelemen LE, Anand SS, Vuksan V et al. Development and evaluation of cultural food frequency questionnaires for South Asians, Chinese, and Europeans in North America. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:1178–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kanaya AM, Kandula N, Herrington D et al. Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) study: objectives, methods, and cohort description. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36:713–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mostøl A. Dietary Assessment—The Weakest Link? [dissertation] Oslo, Norway: University of Oslo; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kumar BN, Grøtvedt L, Meyer HE et al. The Oslo Immigrant Health Profile. Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Institute of Public Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Tinker LF et al. Measurement characteristics of the Women’s Health Initiative food frequency questionnaire. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9:178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bright-See E, Catlin G, Godin G. Assessment of the relative validity of the Ontario Health Survey food frequency questionnaire. J Can Diet Assoc. 1994;55:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lear SA, Birmingham CL, Chockalingam A et al. Study design of the Multicultural Community Health Assessment Trial (M-CHAT): a comparison of body fat distribution in four distinct populations. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Erens B, Primatesta P, Prior G, eds. Health Survey for England 1999. Vol 2: The Health of Minority Ethnic Groups. London, UK: The Stationery Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sproston K, Mindell J, eds. Health Survey for England 2004. Vol 2. Methodology and Documentation. Leeds, UK: The Information Centre; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 50. California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2005 Methodology Series: Report 2—Data Collection Methods. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 51. California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2007 Methodology Series: Report 2—Data Collection Methods. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 52. California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2009 Methodology Series: Report 2—Data Collection Methods. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 53. California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2011–2012 Methodology Series: Report 2—Data Collection Methods. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Healthy Survey 2000–2001 (Cycle 1.1)—Data Sources and Methodology. http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=3359. Published May 8, 2002. Accessed June 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Healthy Survey 2003 (Cycle 2.1)—Data Sources and Methodology. http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=4995. Published June 15, 2004. Accessed June 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Healthy Survey 2005 (Cycle 3.1)—Data Sources and Methodology. http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=22642. Published June 13, 2006. Accessed June 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Statistics Canaada. Canadian Community Healthy Survey 2007 (Cycle 4.1)—Data Sources and Methodology. http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=29539. Published June 18, 2008. Accessed June 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Johnson B, Hackett AF. Eating habits of 11–14-year-old schoolchildren living in less affluent areas of Liverpool, UK. J Hum Nutr Diet. 1997;10(2):135–144. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Johnson B, Hackett A, Roundfield M, Coufopoulos A. An investigation of the validity and reliability of a food intake questionnaire. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2001;14(6):457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Thompson FE, Subar AF. Dietary assessment methodology. In: Coulston A, Boushey C: Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease. 2nd ed.Burlington, MA: Elsevier; 2008:3–39. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pope JF. Pregnant and Postpartum Adolescents’ Appetite Compulsions, Food Preferences, and Reasons for Dietary Change [dissertation]. Knoxville: University of Tennessee; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Baranowski T. 24-Hour recall and diet record methods. In: Willett W, ed. Nutritional Epidemiology. 3rd ed.Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cade J, Thompson R, Burley V, Warm D. Development, validation and utilisation of food-frequency questionnaires—a review. Public Health Nutr. 2002;54:567–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Teufel NI. Development of culturally competent food-frequency questionnaires. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(4 suppl):1173S–1178S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jain MG, Rohan TE, Soskolne CL, Kreiger N. Calibration of the dietary questionnaire for the Canadian Study of Diet, Lifestyle and Health cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6(1):79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rosenmöller DL, Gasevic D, Seidell J, Lear SA. Determinants of changes in dietary patterns among Chinese immigrants: a cross-sectional analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:42 doi:10.1186/1479-5868-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. National Centre for Social Research, University College London. Health Survey for England, 1998: Cardiovascular Disease. Vol 2. Methodology and Documentation. London, UK: The Stationery Office; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 68. National Centre for Social Research, University College London. Health Survey for England 2003. Vol. 3. Methodology and Documentation. London, UK: The Stationery Office; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL et al. Rethinking the concept of acculturation. Am Psychol. 2010;65:237–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]