Abstract

Objective(s):

Periodontal diseases are among prevalent oral health problems which may ultimately lead to severe complications in oral cavity. Herbal products can be designed as single or multicomponent preparations for better oral health. This study aims to review current clinical trials on the effectiveness of herbal products in gingivitis.

Materials and Methods:

Electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, ScienceDirect and Cochrane library were searched with the keywords “gingivitis” in the title/abstract and “plant/ extract/ herb” in the whole text for clinical trials on herbal treatments for gingivitis. Data were collected from 2000 until January 2018. Only papers with English full-texts were included in our study.

Results:

Herbal medicines in the form of dentifrice, mouth rinse, gel, and gum were assessed in gingivitis via specific indices including plaque index, bleeding index, microbial count, and biomarkers of inflammation. Pomegranate, aloe, green tea, and miswak have a large body of evidence supporting their effectiveness in gingivitis. They could act via several mechanisms such as decrease in gingival inflammation and bleeding, inhibition of dental plaque formation, and improvement in different indices of oral hygiene. Some polyherbal formulations such as triphala were also significantly effective in managing gingivitis complications.

Conclusion:

Our study supports the efficacy and safety of several medicinal plants for gingivitis; however, some plants do not have enough evidence due to the few number of clinical trials. Thus, future studies are mandatory for further confirmation of the efficacy of these medicinal plants.

Key Words: Gingivitis, Medicinal plants, Oral diseases, Phytochemicals, Traditional medicine

Introduction

Periodontal diseases, including gingivitis and periodontitis, are amongst the prevalent oral health problems which may ultimately lead to severe conditions in oral cavity (1). Gingivitis is the inflammation of gingiva without apical migration of junctional epithelium which, unless treated, will lead to periodontitis in susceptible patients (1, 2). Gingivitis has a high prevalence among societies. In an epidemiological study in American adults, nearly 55.7% of subjects had a GI index (Löe-Silness Gingivitis Index) higher than 1 (3). Various etiological factors have been introduced regarding periodontal diseases since it is considered a multifactorial disease (4). Biofilm accumulation and pathogens are the key contributors; however, other risk factors can be categorized as modifiable factors such as smoking, obesity, stress, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, and Vitamin D and calcium deficiency, as well as non-modifiable factors like genetic polymorphisms (5). It has been shown that there is a negative correlation between gingivitis and oral-health related quality of life (6).

Mechanical removal of plaque via tooth brush and use of dental floss has been considered as an effective method in controlling gingivitis (7). Nevertheless, adequate time of brushing, efficient cleaning of all tooth surfaces and regular oral hygiene is hard to achieve in every individual due to variations in oral health practices which accounts for high prevalence of gingivitis (8). Therefore, additional approaches such as dentifrices and mouthwashes containing chemical or herbal agents are suggested (9). American Dental Association has approved chlorhexidine (CHX) and essential oils (EO) as antiseptics in mouthwashes (10); though, there have been reports of hypersensitivity, stain formation on teeth surface, oral mucosa irritation, and altered taste with chlorhexidine (10, 11).

Phytotherapy in oral health has received attention lately and a plethora of clinical trials have been conducted in this area (12-16). Herbs are known to have anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and antioxidative effects (17). Herbal products in the forms of dentifrices and mouth rinses can be based on a single natural component, or a mixture of several medicinal plants (18). The aim of this study is to comprehensively review literature and provide an overview upon effectiveness, safety and availability of herbal products for gingivitis.

Materials and Methods

Electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, ScienceDirect and Cochrane library were searched for clinical trials on herbal treatments for gingivitis. The following keywords were used: Gingivitis (title/abstract) AND plant/extract/herb (all fields). We searched for articles in English from 2000 until January 2018 and checked their reference list for additional relevant studies. A total of 1998 articles were collected. Total of 883 duplicate results were excluded. Abstracts and titles were screened and 898 articles were excluded as they were in vitro studies or investigating oral diseases other than gingivitis. Studies on mixtures of chemical and herbal components were also excluded because the pharmacological activity could not be completely attributed to the herbal component. The number of 34 articles were excluded because they were reviews. Nine articles were excluded since the full-texts were not in English. A total of 60 relevant articles were published before 2000 which were excluded as we intend to focus on recent trends. Full-texts for the remainder were obtained. Ten articles were excluded as they were about non-herbal materials (animal and fungal origin).

The included studies were screened for scientific names of herbal agents, their concentrations and types of preparation, duration of study, tests and indices used to evaluate the outcome and characteristics of subjects. Jadad score was used to compare the methodology of the included articles (19). Outcomes were compared between the herbal component and positive/ placebo controls. In case of before-and-after studies, baseline and final records were compared. The arrows (↑ and ↓) show increase and decrease in the specified parameter, respectively.

Results

Single herbal preparations

Aloe vera (Aloe)

Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. (synonym: Aloe barbadensis) or Aloe from the family Asphodelaceae (Liliaceae) (20) is a perennial plant which originates from South Africa, but has also been cultivated in dry subtropical and tropical regions, such as the southern USA (21, 22).

Potentially active compounds of the leaves include water- and fat-soluble vitamins, simple/complex polysaccharides, minerals, organic acids, and phenolic compounds (22).

In a double-blind, randomized clinical study on 45 subjects, daily rinse with 15 ml of aloe solution significantly decreased Gingival index (GI) and Sulcus bleeding index (SBI) after three months. GI, describes the severity of gingivitis (23); while SBI is an index of gingival inflammation in which bleeding is measured from four gingival units (24). The reduction was more pronounced when scaling and root planning was added to this treatment (25). Another study also demonstrated that aloe can be used as an adjunct to scaling to improve clinical parameters such as PI, GI and bleeding on probing (BOP) (26). Plaque index (PI), developed by Silness and Loe in 1964, assesses the thickness of the plaque in the margin of the tooth closest to gums (23). BOP is the earliest clinical symptom of gingivitis and a predictor of periodontal stability described by Lang et al (27). In another study on 120 subjects, aloe 100% solution consumed for 7 days was effective in reducing PI, bleeding index (BI), and modified gingival index (MGI), a score introduced by Lobene in 1985 to assess the severity of gingivitis by non-invasive approaches (28); however, the effectiveness was less than chlorhexidine 2% (CHX) (29). In a clinical trial on 30 subjects, aloe dentifrice showed an efficacy similar to fluoridated dentifrice after 30 days of brushing as they equally reduced PI and gingival bleeding index (GBI) (30). Same results were obtained in a study on 345 subjects who were advised to rinse with aloe or CHX for 30 days (31). In another controlled study, aloe dentifrice was proved equally effective as a control commercial product (Sensodyne) in improving GI and PI indices (32). By contrast, the effect of aloe mouth rinse on PI and GI was compared with CHX and chlorine dioxide in a study for 15 days in which aloe had a significantly lower efficacy (33). The obtained result may be due to the shorter treatment period in comparison to previous studies. Other parameters such as Quigley-Hein plaque index (QHI a modification of PI that evaluates the plaque revealed on the buccal and lingual non-restored surfaces of the teeth (34) and microbial count was significantly reduced in a study on 90 subjects with both aloe and a triclosan containing fluoride dentifrice compared to placebo (35).

Azadirachta indica (Neem)

Azadirachta indica A. Juss or Neem from the family Meliaceae is a tree which is mainly cultivated in the Indian subcontinent (36). The main active components of the plant with important antibacterial activity are nimbidin, nimbinin, and azadirachtin (37).

In a randomized clinical trial on 30 subjects, neem mouthwash was compared to Camellia sinensis (tea) and CHX mouthwash. Both herbal extracts improved GI, PI, OHIS (a simplified version of the OHI which combines the Debris Index and the Calculus Index on 6 tooth surfaces) (38) and pH level better than CHX; however, green tea outperformed neem in PI index (39). In another study, rinsing with neem and CHX mouthwash reduced PI, SBI and GI indices after 4 weeks with no significant difference between the two agents (40). Sharma et al. compared neem mouthwash with mango and CHX. Neem and CHX had similar results in reducing PI and GI but CHX had a more sustained effect after one month (41). Another parameter used to evaluate the effect of neem was interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) levels. Results showed that the reduction of PI, GI, and IL-2 and IFN-γ level with CHX, essential oil, and povidone iodine is statistically more significant than neem (42).

Calendula officinalis (Marigold)

Calendula officinalis L. or marigold from the family Asteraceae (Compositae) is a plant native to Central and Southern Europe, Western Asia and the US, but it is widely cultivated as an ornamental plant in other parts of the world. Whole plant contains terpenoids, quinones, flavonoids, coumarines, volatile oil, and carotenoids (43, 44).

A study involving 240 subjects showed that marigold mouthwash can significantly improve GI, PI, SBI and OHIS indices after 3 months of treatment (45). In another clinical trial without a control group, marigold dentifrice reduced GI, PI and BOP in 40 patients with stablished gingivitis (46).

Camellia sinensis (Green tea)

Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze or tea from the family Theaceae is an evergreen plant originating from China which later spread to other parts of the world. The major chemical components of tea are polyphenols like catechins and flavonoids, as well as methylxanthine alkaloids including caffeine, theobromine, and theophylline. Based on the process, several types of tea are produced amongst which the most popular ones are green tea, as the unfermented type which mostly contains catechin derivatives, and black tea, with the highest degree of fermentation in which the major polyphenols are theaflavins (47).

In a clinical study, green tea improved GI, PI, OHIS and pH level better than CHX or neem (39). PI was equally improved using either green tea or CHX mouthwash in a clinical trial on 30 subjects (48). PI and GI indices were decreased in 110 subjects after using green tea mouthwash for a month (49). Hydroxypropylcellulose strips were used as a sustained release delivery system in a clinical trial on 6 subjects with advanced periodontitis. Combination of green tea and scaling could reduce pocket probing depth (PPD, the distance from the free gingival margin to the bottom of the pocket or gingival sulcus) (50) and peptidase activity after 8 weeks. Green tea also showed in vitro bactericidal activity against Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella nigrescens, and black-pigmented Gram-negative anaerobic rods (51). However, in a study on subjects with chronic gingivitis, green tea had no significant effect on PI, GI and papillary bleeding index (PBI, a score based on sweeping a probe in the sulcus from the line angle to the interproximal contact (52)) (53). Chew candies containing green tea were also effective in reducing SBI and approximal plaque index (API, another periodontal measure defined to further encourage oral hygiene among patients (54)) compared to placebo (55). Green tea gel also improved periodontal health in 49 patients with chronic gingivitis according to GI and PBI parameters compared to placebo control. GI reduction was more pronounced in CHX while PBI was more reduced with green tea; however, plaque scoring system (PSS, modified form of PI) was not improved by the herbal gel (56). Green tea mouthwash performed equally well compared to CHX according to QHI and GI indices as well tooth and tongue stain parameters. Test treatment improved GBI more than CHX (57).

Curcuma longa (Turmeric)

Curcuma longa L. or turmeric from the family Zingiberaceae is a plant native to tropical and subtropical climates, widely cultivated in Asian countries including China and India (58). The main components present in the rhizome are curcuminoids (curcumin, methoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin), as well as the essential oil compounds including turmerones (59, 60).

In a clinical trial, curcumin gel was compared to CHX and a combination of CHX and metronidazole gels. Curcumin was more efficient in reducing PI, MGI, BOP, PPD and IL-1β and CCL28 levels in gingival crevicular fluid (61). In another study, curcumin mouthwash reduced GI and total microbial count to the same level as CHX, and QHI less than CHX (62). Also, in 10 subjects with severe gingivitis, curcumin gel reduced PBI and GI after 3 weeks (63). A combination of turmeric and eugenol resulted in same PI, GI and BAPNA (a method to analyze trypsin like activity of “red” complex microorganisms) values as CHX mouthwash (64).

Lippia sidoides (pepper-rosmarin)

Lippia sidoides Cham. or pepper-rosmarin from the family Verbenaceae is a plant which is distributed mostly in Brazil. The leaves contain essential oil with limonene, β-caryophyllene, p-cymene, camphor, linalool, α-pinene and thymol as major components (65).

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study in 22 subjects, pepper-rosmarin gel failed to reduce GBI or PI in comparison to control; however, GI was significantly improved (66). In another study, PI and GBI scores were improved after rinsing with either pepper-rosmarin or CHX gel (13). Effect of pepper-rosmarin mouthwash on PI, GI and GBI indices were assessed in a study involving 55 subjects which showed a similar efficacy to CHX. Salivary Streptococcus mutans count was also reduced with both treatments (67, 68).

Magnolia officinalis (Magnolia)

Magnolia officinalis L. or magnolia is an endangered deciduous tree from the family Magnoliaceae. Due to the medicinal importance, the tree has been over-harvested to obtain its valuable bark. Magnolol and honokiol with lignan structure are the major phenolic constituents of M. officinalis bark (69, 70).

In a study on 94 subjects, magnolia mouthwash significantly reduced QHI and GI compared to placebo (16). Magnolia and xylitol chewing gum also improved plaque pH, BOP and reduced salivary Streptococcus mutans count after 30 days of treatment (71).

Matricaria chamomilla (Chamomile)

Matricaria chamomilla L. from the family Asteraceae is an annual plant native to eastern and southern parts of Europe; but is also cultivated in several other parts of the world. Numerous phytochemical constituents have been identified in chamomile flower amongst which the most important ones are apigenin, α-bisabolol and cyclic ethers, umbelliferone, and chamazulene (72).

A mouthwash prepared with chamomile extract was as efficient as CHX in reducing visible plaque index (VPI, an index for plaque accumulation and oral hygiene (73)) and GBI (74). Also, in another trial, chamomile mouthwash was compared to pomegranate and miswak mouthwashes in which all herbal treatments could significantly reduce PI and BOP (75).

Ocimum spp. (Basil)

Ocimum spp. or basil belongs to plant family Lamiaceae (Labiatae). The genus Ocimum has around 30 species native to Africa, Asia, and tropical parts of South America (Brazil). The volatile oil of the leaves contains eugenol and methyl eugenol, carvacrol and a sesquiterpine hydrocarbon, caryophyllene. Fresh leaves and stem extract yield some phenolic compounds such as circimaritin, cirsilineol, isothymusin, rosmarinic acid and apigenin which represented antioxidant activity (76, 77).

Ocimum gratissimum reduced GBI and PI to same levels as CHX after 3 months in 30 subjects with gingivitis (78). Ocimum sanctum also reduced GI and PI to same levels as CHX after one month of treatment in 108 subjects (79).

Punica granatum (Pomegranate)

Punica granatum L. or pomegranate from the family Lythraceae, is a tree native to Iran, but is now cultivated in some other countries. Both fruit peel and root cortex are used as medicinal parts which contain ellagic acid, ellagitannins (including punicalagins), punicic acid, flavonoids, anthocyanidins, anthocyanins, and estrogenic flavonols and flavones as well as alkaloid like pelletierine (80-82)

In a short-term study, pomegranate mouthwash enhanced GI index after 4 days better than CHX (83). The effect of pomegranate mouthwash on gingivitis was assessed in a clinical study considering total saliva protein (which correlates with amount of plaque forming bacteria), activity level of aspartate aminotransferase (an indicator of cell injury), α-glucosidase activity (a sucrose degrading enzyme), activity level of the antioxidant enzyme ceruloplasmin, and radical scavenging capacity. All the aforementioned parameters were significantly improved after 4 weeks of treatment (84). In another study, pomegranate mouthwash decreased the streptococci count of saliva, but failed to reduce PI and GBI (though to a lesser extent than CHX) (85). In a trial by Salgado et al. pomegranate gel showed no significant effect on GBI and PI, either (86). By contrast, pomegranate rinse in patients with diabetes mellitus and gingivitis could reduce GBI, PPD, PI and MGI with an efficacy equal to CHX (87). In addition, pomegranate gel accompanied by mechanical debridement reduced PI, GI, PBI and gram-negative bacilli and cocci count (88). Also, pomegranate mouthwash showed similar efficacy to Persica mouthwash (with Salvadora persica as the main ingredient) or Matrica (containing chamomile as the chief active component) regarding PI and BOP indices (75).

Salvadora persica (Miswak)

Salvadora persica L. or Miswak from the family Salvadoraceae is a medicinal plant with a wide geographic distribution is Asia and Africa. The plant is traditionally used as a natural toothbrush to improve oral health in the native areas. The major components from the essential oil of the tree stem are 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol), β-pinene, α-caryophellene, 9-epi-(E)-caryophellene, and β-sitosterol (89, 90).

In a clinical trial, miswak chewing gum reduced GI and SBI compared to placebo; however, it had no effect on PI. It should be mentioned that several patients complained about the unpleasant taste of the preparation (91). Khalessi et al. (2004) also failed to detect a significant improvement in PI by miswak mouthwash; though, GBI and salivary concentrations of S. mutans were successfully reduced (92). A dentifrice containing miswak showed effectiveness similar to a commercial product (Parodontax) in reducing SBI and API (93). In another study, colony forming units of plaque samples were similar after using either Persica (a mouthwash containing miswak extract) or Listerine, but the efficacy was less than CHX (94). In another study QHI and GI indices were applied to compare the use of miswak to regular toothbrush. Best results were obtained when both miswak and toothbrush were used (95). Inactivated (boiled) miswak sticks were compared to active sticks in a clinical trial which obtained same results for both preparations with regard to API, GI and sub-gingival microbiota (96)

Polyherbal preparations

Triphala

Triphala is a traditional multi-component herbal preparation containing three main ingredients, Terminalia bellirica (Gaertn.) Roxb., Terminalia chebula (Gaertn.) Retz., and Phyllanthus emblica L. (Synonym: Emblica officinalis). Triphala mouthwash showed an effectiveness similar to CHX according to PI, GI and Streptococcus count reduction rate; however, triphala had a more pronounced effect on Lactobacillus count (97). Triphala was also compared with CHX in another study on 120 hospitalized periodontal disease subjects and was equally effective in reducing PI and GI (98). Same results were obtained in another study where triphala and CHX were compared in reducing QHI and GI (99). In addition, T. chebula which is an ingredient of triphala was individually evaluated in two trials (Table 1). In a clinical trial, T. chebula mouthwash was able to neutralize salivary pH. It also decreased QHI and GI indices similarly to CHX without any taste alteration and discoloration (100). In another study in 60 subjects, T. chebula mouthwash reduced PI and GI and the effectiveness was equal to CHX (101).

Table 1.

Clinical trials on the use of single medicinal plants for the treatment of gingivitis

| Plant scientific name | Type of preparation | Study design | Jadad score | Duration of study (day) | Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacia arabica | Dentifrice | Randomized, double-blind, crossover controlled trial in 60 subjects with gingivitis-compared to regular toothpaste | 3 | 28 | ↓GI, QHI, BOP: better with test | (121) |

| Aloe vera | Dentifrice | Randomized clinical trial in 45 subjects-group 1 (scaling)/ group 2 (scaling + A. vera) / group 3 (A. vera) | 3 | 42 | ↓PI, GI, PoB, PPD in all groups with best effect in group 2 | (26) |

| Aloe vera | Dentifrice | Randomized, placebo & positively controlled clinical trial in 90 subjects with chronic generalized gingivitis-compared with dentifrice containing fluoride + triclosan | 5 | 168 | ↓GI, QHI, microbial count same in both groups | (122) |

| Aloe vera | Mouthwash | Single-center, single-blind, controlled trial in 85 subjects- compared to CHX or chlorine dioxide | 3 | 15 | ↓PI, GI with better effect by CHX and chlorine | (33) |

| Aloe vera 100% | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, controlled study in 120 healthy subjects with experimental gingivitis -compared with CHX | 2 | 22 | ↓BI, MGI, PI in both groups (CHX was better in PI) | (29) |

| Aloe vera 15 ml | Mouthwash | Controlled clinical trial in 45 subjects with plaque-induced gingivitis in comparison to scaling only | 2 | 90 | ↓GI & SBI Better results with A. vera mouthwash + scaling |

(25) |

| Aloe vera 45% | Dentifrice | Randomized, double-blind, intra-individual & controlled clinical study in 15 subjects with gingivitis-compared with control dentifrice | 4 | 1.5 year | ↓PI, GI same in both groups | (32) |

| Aloe vera 50% | Dentifrice | Randomized, double-blind, parallel, clinical trial in 30 subjects- compared with fluoridated dentifrice | 4 | 30 | ↓PI, GBI same in both groups | (30) |

| Aloe vera 99% | Mouthwash | Randomized, triple-blind, controlled trial in 345 subjects- compared with CHX | 5 | 30 | ↓PI, GI same in both groups | (31) |

| Azadirachta indica 0.01%, Essential oil 0.01% | Mouthwash | Double-blind clinical trial in 80 subjects with gingivitis- compared with CHX and povidone iodine | 5 | 14 | ↓PI, GI IL-2 & IFN-γ in all groups except A. indica |

(42) |

| Azadirachta indica 0.19% | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial in 45 subjects with plaque induced gingivitis-compared with CHX | 2 | 28 | ↓BI, GI, BOP same in both groups |

(40) |

|

Azadirachta indica 50% OR Mangifera indica 50% |

Mouthwash | Clinical trial in 97 subjects with gingivitis-compared with CHX | 5 | 21 | ↓PI Efficacy: CHX=A. indica> M. indica Duration of effect: CHX= 2 months A. indica- M. indica: 21 or 28 d ↓GI Efficacy: CHX=A. indica> M. indica at 21 d or 1 month Duration of effect: CHX= 3 months A. indica- M. indica: 1 & 2 month |

(123) |

| Berberis vulgaris 1% | Gel | Double-blind clinical trial in 45 subjects-compared with Colgate anti-plaque dentifrice | 1 | 21 | ↓PI, GI same in both groups | (118) |

| Boswellia serrata 0.1% & 0.2% | Gum | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 75 subjects with moderate plaque-induced gingivitis | 3 | 14 | ↓PI, GI, PPD, BI with no significant difference between extract & powder | (116) |

| Calendula officinalis (1:3 concentration of tincture in water) | Mouthwash | Placebo-controlled, clinical trial in 240 subjects with gingivitis | 3 | 180 | ↓PI,GI,SBI,OHIS | (45) |

| Calendula officinalis 2% | Dentifrice | Double-blind, clinical trial in 40 subjects with established gingivitis-compared with placebo | 4 | 28 | ↓PI, GI & BOP | (46) |

| Camellia sinensis | Sugar-free dragées | Placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial in 47 subjects | 3 | 28 | ↓SBI, API | (55) |

| Camellia sinensis 5% | Mouthwash | Clinical trial in 30 subjects- compared with CHX | 2 | 30 | ↓QHI, GBI, tooth stain, & tongue stain same in both groups ↓BI in both groups (test was better) |

(57) |

| Camellia sinensis (catechins) 0.25% | Mouthwash | Single blind crossover clinical trial in 30 subjects- compared with CHX | 3 | 15 | ↓PI same in both groups |

(48) |

| Camellia sinensis (Green tea catechin) 1.0 mg/ml | Hydroxy-propyl-cellulose strips as a slow release local delivery system applied in pockets | Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 6 subjects with advanced periodontitis –group1 (scaling + tea) /group 2 (scaling + placebo) /group3 (tea only) /group 4 (placebo) | 1 | 56 |

In vitro bactericidal effects against Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella nigrescens ↓PPD only in group 1 Peptidase activity: ↓in group1 & ↑in group 2 No significant change in groups 3 & 4 Black-pigmented, Gram-negative anaerobic rods: ↓in group 1 & ↑in group 3 No significant change in group 2 |

(51) |

| Camellia sinensis 0.5% OR Azadirachta indica 2% | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, clinical trial in 30 healthy subjects- compared with CHX | 5 | 21 | ↓GI In all groups (better with herbal preparations) ↓PI, Maximum efficacy: 0.5% C. sinensis ↑OHIS, In all groups (better with herbal treatments preparations) ↑salivary pH, higher in herbal treatments |

(124) |

| Camellia sinensis 2% | Mouthwash | Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 110 subjects | 5 | 28 | ↓GI, PI | (49) |

| Camellia sinensis 5% | Mouthwash | Single-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial in 50 subjects with chronic generalized plaque-induced gingivitis | 1 | 35 | ↓PI, GI, PBI but not statistically significant |

(53) |

| Cinnamomum zeylanicum 20% | Mouthwash | Randomized, triple-blind, controlled trial, a three-group parallel study in 105 subjects- compared with CHX | 4 | 30 | ↓GI, QHI | (125) |

| Copaifera sp. 10% | Gel | Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial in 23 subjects with experimental gingivitis | 5 | 21 | ↓GBI, GI, PI compared with basline but no significant difference between groups | (126) |

| Curcuma longa 10 mg/100 ml | Mouthwash | Clinical trial in 100 subjects- compared with CHX | 3 | 21 | ↓GI & total microbial count: Same in both groups ↓QHI: in both groups (CHX was better) |

(127) |

| Curcuma longa extract 1% | Gel | Uncontrolled pilot clinical trial in 10 subjects with severe gingivitis | 1 | 21 | ↓PBI,GI | (63) |

| Curcuma sp. 0.1% + eugenol 0.01% | Mouthwash | Clinical trial in 60 subjects with mild to moderate gingivitis-compared with CHX | 0 | 21 | ↓GI, PI, BAPNA Numerically but not statistically significant better than CHX |

(64) |

| Curcumin (from Curcuma longa) 10 mg/ g | Gel | Randomized, double-blind clinical trial in 60 subjects- compared to CHX 10 mg & CHX-MTZ 10 mg | 5 | 60 | MGI, PI, BOP, PPD: no significant change ↓IL-1β & CCL28 levels in gingival crevicular fluid: test >CHX-MTZ >CHX |

(61) |

| Curcumin (from Curcuma longa) 1% | Gel | Randomized clinical trial in 30 subject with severe gingivitis- compared with curcumin + SRP treatment | 2 | 21 | ↓SBI, PI, GI Better in curcumin + SRP |

(114) |

| Cymbopogon spp. oil 0.25% | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, controlled parallel designed clinical trial in 60 subjects-compared with CHX | 5 | 21 | ↓PI, GI and Cymbopogon was numerically but not statistically better than CHX |

(128) |

| Enteromorpha linza 1.5 mg/ ml | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial in 55 subjects – compared with Listerine | 2 | 42 | ↓GI, QHI, GBI, bacterial strains (Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia) Same in both groups |

(129) |

|

Eucalyptus

globulus 0.6%- OR 0.4%- |

Chewing gum | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, trial in 97 subjects with gingivitis | 4 | 98 | ↓GI, PPD, BOP, plaque accumulation at both concentrations, No significant change in clinical attachment level |

(115) |

| Eugenia uniflora 3% | Dentifrice | Randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial in 50 subjects–compared with fluoridated triclosan dentifrice | 5 | 7 | ↓OHI only in control ↓GBI same in both groups |

(130) |

| Garcinia mangostana | Gel | Controlled clinical trial in 31 subjects with periodontal pocket- compared with scaling only | 2 | 90 | ↓BOP, PI, GI, PPD, clinical attachment, means percentage of cocci | (131) |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra 30% | Mouthwash | Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 20 subjects | 0 | 14 | ↓PI, GI |

(132) |

| Ilex rotunda 0.6% | Dentifrice | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 100 subjects-compared with normal dentifrice without active agents | 5 | 84 | ↓GI,QHI | (133) |

| Ixora coccinea 0.2% | Mouthwash | Randomized, controlled clinical trial in 20 subjects- compared with CHX | 2 | 28 | ↓GI, QHI, BOP: same in both groups ↑Lobenne tooth staining index in CHX |

(134) |

| Lactuca sativa 200 mg nitrate | Daily consumption (systemic administration) | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 39 subjects with chronic gingivitis | 5 | 14 | No significant change in PCR ↓GI Lower in test ↑SNL higher in test |

(135) |

| Lippia sidoides 1% | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, parallel-armed pilot study in 55 subjects- compared with CHX | 4 | 7 | ↓GI, PI, GBI No significant difference between test and CHX |

(68) |

| Lippia sidoides 1% | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, parallel-armed pilot study in 55 subjects- compared with CHX | 4 | 7 | ↓GI, GBI, PI, salivary Streptococcus mutans | (67) |

| Lippia sidoides 10% | Gel | Parallel controlled clinical trial in 30 subjects- compared with CHX | 5 | 90 | ↓PI, GBI same in both groups |

(13) |

| Lippia sidoides 10% | Gel | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover clinical trial in 22 subjects with experimental gingivitis | 4 | 21 | ↓GI No significant change in GBI & PI |

(66) |

| Macleya cordata 0 .005% & Prunella vulgaris 0.5% | Dentifrice | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial in 40 subjects with gingivitis | 2 | 84 | ↓PI ↓CPITN & PBI numerically but not statistically significant |

(136) |

| Magnolia officinalis (magnolol 0.10% + honokiol 0.07%) | Chewing gum | Randomized, double-blind, controlled intervention trial in 117 subjects-compared with xylitol chewing gum or placebo chewing gum | 5 | 30 | Plaque pH Efficiency in maintaining the pH: Magnolia > Xylitol> Control No significant difference in BOP ↓Salivary Streptococcus mutans count |

(117) |

| Magnolia officinalis 0.3% | Dentifrice | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 94 subjects | 5 | 180 | ↓QHI,GI | (137) |

| Matricaria chamomilla 1% | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study in 30 subjects- compared with CHX | 4 | 15 | ↓VPI, GBI Same in CHX & Test |

(74) |

| Melaleuca sp. 2.5% | Gel | Double-blind, longitudinal, non-crossover study in 49 subjects with severe chronic gingivitis-compared with CHX | 3 | 56 | GI: CHX>test > control PSS: CHX> control > test (not significant) PBI: Test> CHX> control |

(56) |

| Menthol 18 mg % | Mouthwash | Double-blind, crossover, controlled clinical trial in 30 subjects-compared with CHX 0.2% & deionized water | 1 | 5 | ↓PI, GI, GBI Less effective than CHX |

(112) |

| Ocimum gratissimum | Mouthwash | Randomized, parallel, double-blind clinical trial in 30 subjects-compared with CHX | 5 | 90 | ↓PI, GBI same in both groups |

(138) |

| Ocimum sanctum 4% | Mouthwash | Randomized, triple blind, controlled trial in 108 subjects- compared with CHX | 5 | 30 | ↓PI, GI same in both groups | (79) |

| Polygonum aviculare 1 mg/ml | Mouthwash | Uncontrolled clinical trial in 51 subjects with gingivitis | 1 | 14 | ↑PI (however, the consistency of this plaque permitted its mechanical flushing easily) ↓GI |

(139) |

|

Punica granatum

Or Matricaria chammomila Or Salvadora persica |

Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 104 subjects with gingivitis | 2 | 28 | ↓PI, Same in all groups ↓BOP Better in herbal groups Better taste and acceptability in P. granatum |

(75) |

| Punica granatum 10% | Gel | Placebo-controlled, crossover, double-blind study in 23 subjects | 4 | 21 | No significant change in PI, GBI | (140) |

| Punica granatum 6.25% | Mouthwash | Randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical trial in 35 subjects-compared with CHX | 4 | 7, 12 | ↓GBI, PI only in CHX ↓saliva streptococci count in both groups (CHX was better ) |

(85) |

| Punica granatum 0.05% | Gel | Clinical trial in 40 subjects- group 1(mechanical debridement + test gel)/ group 2 (mechanical debridement + control gel)/ group 3 (test gel only)/ group 4 (control gel only) | 2 | 21 | ↓PI, GI, PBI in groups 1 & 2 but not in groups 3 & 4 Significant difference at the end was seen only in PBI among groups Gram-negative cocci & bacilli (less in groups 1 & 3) & Gram-positive cocci & bacilli same in all groups Best results with group 1 |

(141) |

| Punica granatum 30% | Mouthwash | Randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 32 subjects with moderate gingivitis | 1 | 28 | ↓Saliva total protein, AST activity & α-glucosidase activity ↑ceruloplasmin activity & radical scavenging capacity |

(84) |

| Punica granatum 50-75 mg/ml | Mouthwash | Randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 45 subjects- compared with CHX | 5 | 4 | ↓GI with best effect by P. granatum |

(83) |

| Punica granatum var pleniflora 10 g in 240 ml | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, clinical trial in 80 subjects with diabetes mellitus & gingivitis- compared with CHX | 5 | 14 | ↓GBI, PPD, PI same in both groups ↓MGI better in test |

(87) |

|

Rabdosia rubescens

1: 960 mg of the herb +1000 mg simulating agent 2: 1000 mg of the herb + 960 mg simulating agent |

Drop pill or tablets of simulation agent | Randomized, double-blind, double-simulation, positive-controlled parallel multi-center trial in 136 subjects with gingivitis | 4 | 5 | ↓Major symptoms of Gingivitis 1 same as 2 ↓Minor symptoms of Gingivitis 1 same as 2 except in dry mouth and thirst which 1 was better than 1 Therapeutic effect 1>2 |

(142) |

| Salvadora persica | Miswak (chewing stick) | Randomized, single-blind, parallel-armed study in 30 subjects with mild to moderate gingivitis -group 1 (only toothbrush)/ group 2 (toothbrush+ Miswak)/ group 3 (only Miswak) | 1 | 56 | ↓GI: Group 2 > group 1 = group 3 ↓QHI: group 2 > group 1 > group 3 |

(95) |

| Salvadora persica | Miswak (chewing stick) | Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial in 58 subjects with gingivitis | 5 | 21 | ↓API & GI: No significant difference between groups composition of sub-gingival microbiota was same in both groups |

(96) |

| Salvadora persica 0.6% | Gum | Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 60 subjects with plaque induced moderate gingivitis- Either combined with SRP treatments or solely | 4 | 14 | ↓GI, SBI No significant difference in PI |

(91) |

| Salvadora persica 15 drops in 15 ml of water | Mouthwash | Randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial in 32 subjects with gingivitis-compared with CHX | 1 | 14 | ↓CFU of plaque samples: CHX> S. persica No in vitro antibacterial effects |

(94) |

| Salvadora persica 15 drops into 15 ml water | Mouthwash | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial in 28 subjects | 2 | 21 | No significant change in PI ↓GBI ↓Salivary concentrations of Streptococcus mutans |

(92) |

| Salvadora persica OR Parodontax OR Silca | Dentifrice | Controlled, clinical trial in 66 non-smoking subjects -compared with Colgate total | 3 | 21 | ↓SBI: Parodontax = S. persica > colgate total ↓API: same in all groups |

(93) |

| S alvadora persica ( 940 mg) + Aloe vera | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind controlled clinical trial in 76 patients under mechanical ventilation in ICU ward- compared with CHX | 3 | 4 | ↓GI Better in test |

(143) |

| Schinus terebinthifolius 0.3125% | Mouthwash | Randomized, controlled, triple-blind, phase II clinical trial in 27 subjects with plaque induced gingivitis- compared with CHX | 5 | 10 | ↓OHIS (amount of biofilm) only in CHX ↓GBI same in both groups |

(15) |

| Scutellaria baicalensis 0.5% | Dentifrice | Randomized, double-blind clinical trial in 40 subjects with experimental gingivitis-compared with fluoride toothpaste | 5 | 21 | PI, GI, VF% | (144) |

| Streblus asper 80 mg/ml | Mouthwash | Single-blind, crossover clinical study in 30 subjects-compared with distilled water | 2 | 4 | ↓GI No significant change in PI, Streptococcus mutans count in plaque & saliva total salivary bacterial count |

(145) |

| Terminalia chebula 10% | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, controlled study in 78 subjects with gingivitis- compared with CHX | 4 | 14 | ↓QHI, GI, pH same in both groups |

(146) |

| Terminalia chebula 10% | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial in 60 subjects- compared with CHX | 5 | 28 | ↓GI, PI Same in both groups |

(101) |

| Vaccinium myrtillus (250 g (1) or 500 g (2)) | Daily oral consumption | Placebo-controlled clinical trial in 24 subjects with gingivitis- compared with standard care (debridement) | 2 | 7 | ↓BOP in standard care, 2 & placebo, but not 1 ↓IL-1β, IL-6, VEGF in gingival crevicular fluid only in group 2 |

(147) |

GI: Loe & Silness gingival index; SBI: Muhlemann & Son's Sulcus bleeding index; PI: plaque index; PBI: papillary bleeding index; PHPI: Patient Hygiene Performance Index; CPITN: community periodontal index of treatment needs; BOP: Bleeding on probing; GBI: Gingival Bleeding index; VF%: biofilm vitality; API: approximal plaque index; OHIS: simplified Greene & Vermillion’s Oral Hygiene Index; BAPNA: The N-benzoyl-l-arginine-p-nitroanilide (BAPNA) assay used to analyze trypsin like activity of "red" complex microorganisms; CHX: chlorhexidine; QHI: Quigley & Hein plaque index; MGI: modified gingival index; PPD: probing pocket depth; MMP-8: matrix metalloproteinase-8;BA: biofilm accumulation; SAnB: anaerobic (SAnB) & aerobic (SAB) bacterial counts; NPI: Navy Plaque Index; PPI: planimetric plaque index; VPI: visible plaque index; PPBI: The periodontal probe bleeding index of Ainamo & Bay; PSS: plaque staining score; SBI: sulcus bleeding index; PSS: plaque staining score; LB: Lobene index; Parodontax: chamomile, echinacea, sage, rhatany, myrrh & peppermint oil; SRP: Scaling and Root Planing; PHP: patient hygiene performance; PMA: Proximal Marginal and attached gingival index; SNL: Salivary Nitrate Level; MTZ: metronidazole, IL: interleukin, IFN: interferon

Miscellaneous polyherbal preparations

A transmucosal herbal periodontal patch containing a mixture of herbs including Centella asiatica (gotu kola), Echinacea purpurea, and Sambucus nigra (elderberry) was clinically effective in reducing GI and gingival crevicular fluid β-glucuronidase (BG) enzymatic activity (135). The GCF BG level reflects the quantity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes found in the sulcus and may be a more accurate assessment of inflammation found in the periodontal sulcus than subjective clinical signs of inflammation (136). HM-302 is a mixture of the same herbs used to treat gingivitis in a study (Table 2). Its effect was compared to Listerine, cetylpyridinum chloride or water. PI, GI and BOP deteriorated in all groups except HM-302 (137).

Table 2.

Clinical trials on the effectiveness of polyherbal formulations for the treatment of gingivitis

| Arimedadi oil | Mouthwash | Clinical trial in 45 subjects with mild to moderate gingivitis- compared with CHX | 3 | 21 | ↓GI, PI same in both groups | (148) |

| Essential oil mixture (thymol, eugenol and eucalyptus) | Dentifrice | Placebo-controlled double-blind, parallel, clinical study in 104 subjects | 3 | 180 | ↓QHI,GI | (149) |

| Listerine | Mouthwash | Randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial in 32 subjects with gingivitis-compared with CHX | 1 | 14 | ↓CFU of plaque samples: CHX> Listerine No in vitro antibacterial effects |

(94) |

| Parodontax | Dentifrice | Randomized, double-blind clinical trial in 30 subjects-compared with standard fluoridated dentifrice | 4 | 21 | No significant change in QHI ↓GI only in test |

(150) |

| Polyherbal preparation | Dentifrice | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 66 subjects | 5 | 168 | ↓BOP, PPD, SAnB, QHI | (105) |

| Polyherbal preparation | Dentifrice | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 60 subjects | 4 | 84 | ↓GI, BOP, SAnB | (106) |

| Polyherbal preparation | Gel & powder | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial in 113 subjects with chronic generalized gingivitis -compared with CHX | 5 | 168 | ↓GI, PI, microbial count same in test groups and CHX No significant difference between gel & powder |

(151) |

| Polyherbal preparation | Mouthwash | A Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 17 subjects with gingivitis | 5 | 84 | No significant difference in PI, GI & relative abundance of two periodontal pathogens |

(152) |

| Polyherbal preparation | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 60 subjects with gingivitis-compared with CHX | 3 | 14 | ↓QHI, MGI, GBI Same in herbal test and CHX |

(9) |

| Polyherbal preparation | Mouthwash | Clinical study Phase I in 30 subjects with periodontitis Phase II in 34 subjects with gingivitis- compared with CHX |

1 | Phase I: 28, Phase II: 14 |

Phase I ↓PPD, BOP, clinical attachment Efficiency (numerically but not statistically significant): CHX>test>placebo Phase II ↓GI, BOP (numerically but not statistically significant): test = CHX > placebo ↓PI: same in all 3 groups |

(108) |

| Polyherbal preparation | Mouthwash + sub-gingival irrigator | Randomized, double-blind clinical study in 89 subjects-group1(irrigator + test mouthwash)/group 2 (irrigator+ conventional mouthwash)/group 3(conventional mouthwash only) | 3 | 90 | ↓GI in group 2, group 1, but not in group 3 ↓SBI only in group 1 ↓PI in all groups No significant change in PPD |

(153) |

| Polyherbal preparation | Transmucosal herbal periodontal patch | Randomized, single-center, double-blind placebo-controlled, crossover, longitudinal phase II trial in 50 subjects with gingivitis | 3 | 15 | ↓GI ↓gingival crevicular fluid β-glucuronidase enzymatic activity |

(102) |

| Triphala (P. emblica, T. bellirica, and T. chebula) 10 g in 10 ml water | Mouthwash | Randomized ,double-blind, multicenter clinical trial in 120 hospitalized periodontal disease subjects-compared with CHX | 5 | 15 | ↓PI, GI same in both groups | (98) |

| Triphala 0.6% (P. emblica, T. bellirica, and T. chebula) | Mouthwash | Controlled clinical trial in 1431 healthy subjects -compared with CHX and placebo | 3 | 270 | ↓PI, GI, Streptococcus count in both groups ↓Lactobacilli count more pronounced in test group |

(97) |

| Triphala 10% (P. emblica, T. bellirica, and T. chebula) | Mouthwash | Randomized, double-blind, crossover study in 120 healthy subjects- compared with CHX | 5 | 30 | ↓QHI, GI same in both groups | (154) |

GI: Loe & Silness gingival index; SBI: Muhlemann & Son's Sulcus bleeding index; PI: plaque index; PBI: papillary bleeding index; CHX: chlorhexidine; QHI: Quigley & Hein plaque index; PPD: probing pocket depth; SAnB: anaerobic bacterial count

A Sri-Lanka polyherbal preparation containing Acacia chundra, Adhatoda vasica, Mimusops elengi, Piper nigrum, Pongamia pinnata, Quercus infectoria, Syzygium aromaticum, Terminalia chebula, and Zingiber officinale significantly improved QHI, PPD, BOP indices, as well as the salivary aerobic and non-aerobic bacterial counts (138). In another study in 60 subjects, same preparation reduced GI, BOP and salivary aerobic and non-aerobic bacterial counts (139).

Another polyherbal preparation containing hydroalcoholic extracts of Zingiber officinale, Rosmarinus officinalis, and Calendula officinalis was evaluated in 60 subjects. MGI, GBI and QHI indices were improved to the same levels as CHX (9).

Rinsing with a polyherbal mouthwash (Salvia officinalis, Mentha piperita, menthol, Matricaria chamomilla, Commiphora myrrha, Carvum carvi, Eugenia caryophyllus and Echinacea purpura) accompanied by a sub-gingival irrigator had significant effect on PI, GI and SBI indices (148).

Radvar et al. prepared a polyherbal mouthwash using Salix alba, Malva sylvestris, and Althaea officinalis herbs which was evaluated in subjects with either gingivitis or periodontitis (Table 2). CHX or test mouthwash were not significantly different than placebo control in improving PPD, BOP and clinical attachment in those with periodontitis; however, they successfully reduced GI and BOP (145).

A dentifrice containing gotu kola and magnolia was compared with conventional toothpastes and decreased PHP, PMA and malodor indices after 14 days (149). PMA index is an easy method to help figure out the inflammatory portion from the normal portion at the divided areas by comparing each side as papillary, marginal and attached gingiva (150). PHP is a simplified patient hygiene performance evaluation.

Phytochemicals

Menthol

Menthol is a monoterpene which is found in different types of mint, as well as several other plants of the Lamiaceae family. The compound is widely used in food industries as a natural flavoring agent, and is also a main part of several oral health products like dentifrices, chewing gums, and mouthwashes (151). A solution of menthol showed less effectiveness in reducing PI, GI and GBI as compared to CHX in 30 subjects in a clinical trial (124).

Curcumin

Curcumin is a secondary metabolite with diarylheptanoid structure which is mainly extracted from the rhizome of turmeric (Curcuma longa) and has shown significant biological activities like antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective effects (152). Curcumin massaged on gingiva in addition to SRP treatments significantly reduced GI, PI and SBI indices compared to baseline (111).

Discussion

Herbal elements are gaining attention as both preventive plaque control approaches and as adjunctive treatments. Among single herbal preparations, many studies have focused on Aloe vera (aloe), Punica granatum (pomegranate), Salvadora persica (miswak) and Camellia sinensis (tea). Polyherbal mixtures have also been studied regarding their effect on the reduction of microbial count and plaque index and other measures. Triphala, for instance is a mouth rinse composed of T. bellirica, T. chebula, and P. emblica which showed positive effects similar to that of CHX (97-99).

Plant secondary metabolites including menthol from mint species and curcumin from turmeric also showed considerable therapeutic activity for the management of gingivitis-induced inflammation, bleeding, and plaque formation (61, 111, 124).

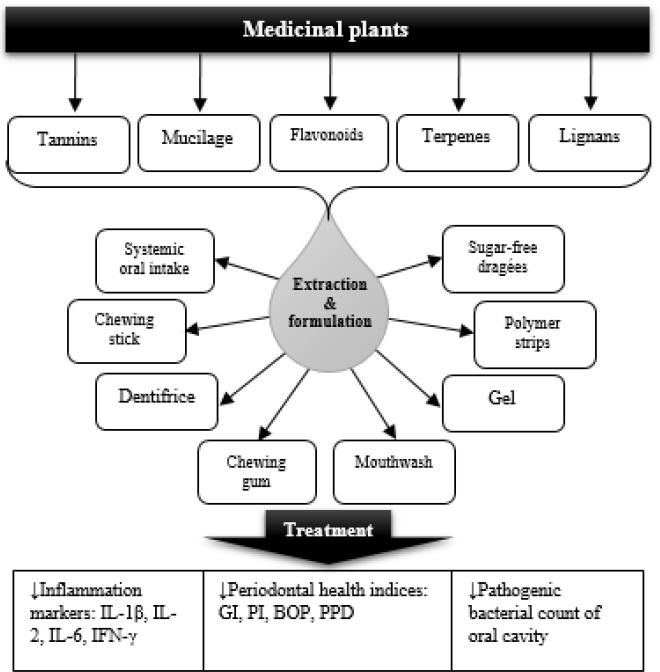

There were a wide diversity of dosage forms and formulations in different studies (Figure 1). Mouthwashes and dentifrices were the most popular forms of administration (Table 1). Green tea has been administered as various dosage forms such as mouth rinse, candies and slow release local delivery systems (39, 51, 55). Some plants like eucalyptus (114), frankincense (106), miswak (91), and magnolia (122) were prepared as chewing gum which might be a favorable dosage form specially for youngsters. Some other extracts such as turmeric (63) and barberry (105) were formulated as gels which, considering the safety of the plant used, can be applied to the damaged areas and would be of great interest in children who might have poor degree of cooperation in using mouthwashes or dentifrices.

Figure 1.

Medicinal plants, active components, formulations, and mechanisms in management of gingivitis. IL: interleukin, IFN: interferon, GI: gingivitis index, PI: plaque index, BOP: bleeding on probing index, PPD: periodontal pocket depth

The main mechanisms by which herbal elements improve the condition of periodontium are described in Figure 1. Immediate bleeding is a result of inflammation in gummy tissues. A combination of host susceptibility and microbial accumulation in form of plaque culminates in inflammation. One of the main mechanisms of medicinal plant to control gingivitis is their anti-inflammatory activity. Some medicinal plants such as pomegranate, tea, and chamomile are rich sources of flavonoids and tannins which are potent anti-inflammatory and astringent phytochemicals and thus, can control both bleeding and inflammation. Aside from different bleeding and inflammation indices reduced during the studies (Table 1), some trials have measured the crevicular level of inflammation biomarkers which strongly support the anti-inflammatory activity of herbal drugs (61).

Another important effect is to control the microflora of oral cavity. Several studies have demonstrated the positive role of herbal extracts to reduce the bacterial count of oral pathogens and plaque formation (Table 1). Rinsing with herbal mouth washes or applying herbal dentifrices, as well as all other sorts of application, can show bactericidal effect and counteract bacterial metabolism (153, 154).

Also, some studies assessed the effect of a combination of herbal treatments along with conventional mechanical dental practices such as scaling (50) which showed a synergistic effect; suggesting that herbal products can be used as a complementary therapy to improve the effectiveness of conventional therapies (25).

Conclusion

Taken together, this paper supports the efficacy of several medicinal plants for the management of gingivitis based on the current clinical evidence; however, available clinical data has several limitations such as short course of study, Small sample size, and lack of blinding which remains the effectiveness of some preparations to be unclear. Thus, future well-designed clinical studies are essential in case of several medicinal plants for their efficacy to be confirmed in gingivitis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Al-Mubarak S, Ciancio S, Baskaradoss JK. Epidemiology and diagnosis of periodontal diseases: recent advances and emerging trends. Int J Dentistry. 2014;2014:953646. doi: 10.1155/2014/953646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalili J. Periodontal disease: an overview for medical practitioners. Lik Sprava. 2008;(3-4):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Lee S, Hujoel P, Su M, Zhang W, Kim J, et al. Prevalence and severity of gingivitis in American adults. Am J Dent. 2010;23:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al Jehani YA. Risk factors of periodontal disease: review of the literature. Int J Dent. 2014;2014:182513. doi: 10.1155/2014/182513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 5.Genco RJ, Borgnakke WS. Risk factors for periodontal disease. Periodontol. 2013;62:59–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2012.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Souza Barbosa T, Gavião MBD, Mialhe FL. Gingivitis and oral health-related quality of life: a literature review. Braz DentSci. 2015;18:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sowinski J, Petrone DM, Wachs GN, Chaknis P, Kemp J, Sprosta AA, et al. Efficacy of three toothbrushes on established gingivitis and plaque. Am J Dent. 2008;21:339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu L, Petersen PE, Wang HY, Bian JY, Zhang BX. Oral health knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of adults in China. Int Dent J. 2005;55:231–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2005.tb00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahyari S, Mahyari B, Emami SA, Malaekeh-Nikouei B, Jahanbakhsh SP, Sahebkar A, Mohammadpour AH. Evaluation of the efficacy of a polyherbal mouthwash containing Zingiber officinale, Rosmarinus officinalis and Calendula officinalis extracts in patients with gingivitis: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;22:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metushaj A. Epidemiology of Periodontal Diseases. Anglisticum. 2015;3:136–140. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdollahi M, Rahimi R, Radfar M. Current opinion on drug-induced oral reactions: a comprehensive review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;3:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaziri S, Mojarrab M, Farzaei MH, Najafi F, Ghobadi A. Evaluation of anti-aphthous activity of decoction of Nicotiana tabacum leaves as a mouthwash: a placebo-controlled clinical study. J Trad Chin Med. 2016;36:160–164. doi: 10.1016/s0254-6272(16)30022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereira SLS, Praxedes YCM, Bastos TC, Alencar PNB, da Costa FN. Clinical effect of a gel containing Lippia sidoides on plaque and gingivitis control. Eur J Dent. 2013;7:28–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhingra K. Aloe vera herbal dentifrices for plaque and gingivitis control: a systematic review. Oral Dis. 2014;20:254–267. doi: 10.1111/odi.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freires IDA, Alves LA, Ferreira GLS, Jovito VDC, Castro RDD, Cavalcanti AL. A randomized clinical trial of Schinus terebinthifolius mouthwash to treat biofilm-induced gingivitis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013:873–907. doi: 10.1155/2013/873907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hellström MK, Ramberg P. The effect of a dentifrice containing magnolia extract on established plaque and gingivitis in man: a six-month clinical study. Int J Dent Hygiene. 2014;12:96–102. doi: 10.1111/idh.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heydarpour F, Abasabadi M, Shahpiri Z, Vaziri S, Nazari HA, Najafi F, et al. Medicinal plant and their bioactive phytochemicals in the treatment of recurrent aphthous ulcers: a review of clinical trials. Pharmacog Mag. 2018;12:27–39. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Wong RWK, McGrath C, Hagg U, Seneviratne CJ. Natural compounds containing mouthrinses in the management of dental plaque and gingivitis: a systematic review. Clin Oral Invest. 2014;18:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00784-013-1033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jadad AR, Enkin M, Jadad AR. Randomized controlled trials: questions, answers, and musings. Wiley Online Library; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.López A, de Tangil MS, Vega-Orellana O, Ramírez AS, Rico M. Phenolic constituents, antioxidant and preliminary antimycoplasmic activities of leaf skin and flowers of Aloe vera (L) burm f (syn a barbadensis Mill) from the Canary Islands (spain) Molecules. 2013;18:4942–4954. doi: 10.3390/molecules18054942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wynn RL. Aloe vera gel: Update for dentistry. Gen Dent. 2005;3:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radha MH, Laxmipriya NP. Evaluation of biological properties and clinical effectiveness of Aloe vera: a systematic review. J Trad Complement Med. 2015;5:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Löe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodont. 1967;38:Suppl:610–616. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mühlemann H, Son S. Gingival sulcus bleeding--a leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Helv Odontol Acta. 1971;15:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ajmera N, Chatterjee A, Goyal V. Aloe vera: it’s effect on gingivitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:435–438. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.118312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kripal K, Kumar RKV, Rajan RSS, Rakesh MP, Jayanti I, Prabhu SS. Clinical effects of commerically available dentifrice containing Aloe vera versus Aloe vera with scaling and scaling alone: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2014;5:508–516. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang NP, Adler R, Joss A, Nyman S. Absence of bleeding on probing an indicator of periodontal stability. J Clin Periodont. 1990;17:714–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1990.tb01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lobene R, Weatherford T, Ross N, Lamm R, Menaker L. A modified gingival index for use in clinical trials. Clin Prev Dent. 1985;8:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chandrahas B, Jayakumar A, Naveen A, Butchibabu K, Reddy PK, Muralikrishna T. A randomized, doubleblind clinical study to assess the antiplaque and antigingivitis efficacy of Aloe vera mouth rinse. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:543–548. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.106905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Oliveira SM, Torres TC, Pereira SL, Mota OM, Carlos MX. Effect of a dentifrice containing Aloe vera on plaque and gingivitis control a double-blind clinical study in humans. J Appl Oral Sci. 2008;16:293–296. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572008000400012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karim B, Bhaskar DJ, Agali C, Gupta D, Gupta RK, Jain A, et al. Effect of Aloe vera mouthwash on periodontal health: triple blind randomized control trial. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2014;13:14–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Namiranian H, Serino G. The effect of a toothpaste containing Aloe vera on established gingivitis. Swed Dent J. 2012;36:179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeturu SK, Acharya S, Urala AS, Pentapati KC. Effect of Aloe vera, chlorine dioxide, and chlorhexidine mouth rinses on plaque and gingivitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2016;6:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quigley GA, Hein JW. Comparative cleansing efficiency of manual and power brushing. J Am Dent Assoc. 1962;65:26–29. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1962.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pradeep AR, Agarwal E, Naik SB. Clinical and microbiologic effects of commercially available dentifrice containing Aloe vera: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2012;83:797–804. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar VS, Navaratnam V. Neem (Azadirachta indica): Prehistory to contemporary medicinal uses to humankind. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2013;3:505–514. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60105-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lakshmi T, Krishnan V, Rajendran R, Madhusudhanan N. Azadirachta indica: a herbal panacea in dentistry - an update. Pharmacogn Rev. 2015;9:41–44. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.156337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greene JG, Vermillion JR. The simplified oral hygiene index. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68:7–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1964.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balappanavar AY, Sardana V, Singh M. Comparison of the effectiveness of 05% tea 2% neem and 02% chlorhexidine mouthwashes on oral health: a randomized control trial. Indian J Dent Res. 2013;24:26–34. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.114933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chatterjee A, Saluja M, Singh N, Kandwal A. To evaluate the antigingivitis and antipalque effect of an Azadirachta indica (neem) mouthrinse on plaque induced gingivitis: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:398–401. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.92578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma R, Hebbal M, Ankola AV, Murugaboopathy V, Shetty SJ. Effect of two herbal mouthwashes on gingival health of school children. J Tradit Complement Med. 2014;4:272–278. doi: 10.4103/2225-4110.131373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma S, Saimbi CS, Koirala B, Shukla R. Effect of various mouthwashes on the levels of interleukin-2 and interferon-γ in chronic gingivitis. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2007;32:111–114. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.32.2.u01p135561161476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muley B, Khadabadi S, Banarase N. Phytochemical constituents and pharmacological activities of calendula officinalis linn (asteraceae): a review. Trop J Pharmaceut Res. 2009;8:455–465. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshikawa M, Murakami T, Kishi A, Kageura T, Matsuda H. Medicinal flowers. iii. marigold.(1): hypoglycemic, gastric emptying inhibitory and gastroprotective principles and new oleanane-type triterpene oligoglycosides, calendasaponins a, b, c, and d, from egyptian calendula officinalis. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) . 2001;49:863–870. doi: 10.1248/cpb.49.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khairnar MS, Pawar B, Marawar PP, Mani A. Evaluation of calendula officinalis as an anti-plaque and anti-gingivitis agent. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:741–747. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.124491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amoian B, Moghadamnia AA, Mazandarani M, Amoian MM, Mehrmanesh S. The effect of calendula extract toothpaste on the plaque index and bleeding in gingivitis. Res J Med Plant. 2010;4:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharangi A. Medicinal and therapeutic potentialities of tea (camellia sinensis l)–a review. Food Res Int. 2009;42:529–535. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaur H, Jain S, Kaur A. Comparative evaluation of the antiplaque effectiveness of green tea catechin mouthwash with chlorhexidine gluconate. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18:178–182. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.131320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarin S, Marya C, Nagpal R, Oberoi SS, Rekhi A. Preliminary clinical evidence of the antiplaque, antigingivitis efficacy of a mouthwash containing 2% green tea - a randomised clinical trial. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2015;13:197–203. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a33447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leroy R, Eaton KA, Savage A. Methodological issues in epidemiological studies of periodontitis-how can it be improved? BMC Oral Health. 2010;10:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirasawa M, Takada K, Makimura M, Otake S. Improvement of periodontal status by green tea catechin using a local delivery system: a clinical pilot study. J Periodontal Res. 2002;37:433–438. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2002.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barnett M, Ciancio S, Mather M. The modified papillary bleeding index-comparison with gingival index during the resolution of gingivitis. J Prev Dent. 1980;6:135–138. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jenabian N, Moghadamnia AA, Karami E, Mir PBA. The effect of Camellia sinensis (green tea) mouthwash on plaque-induced gingivitis: a single-blinded randomized controlled clinical trial. DARU J Pharm Sci. 2012;20:39. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-20-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klages U, Weber AG, Wehrbein H. Approximal plaque and gingival sulcus bleeding in routine dental care patients: relations to life stress, somatization and depression. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:575–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krahwinkel T, Willershausen B. The effect of sugar-free green tea chew candies on the degree of inflammation of the gingiva. Eur J Med Res. 2000;5:463–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soukoulis S, Hirsch R. The effects of a tea tree oil-containing gel on plaque and chronic gingivitis. Aust Dent J. 2004;49:78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2004.tb00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Priya BM, Anitha V, Shanmugam M, Ashwath B, Sylva SD, Vigneshwari SK. Efficacy of chlorhexidine and green tea mouthwashes in the management of dental plaque-induced gingivitis: a comparative clinical study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6:505–509. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.169845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maheshwari RK, Singh AK, Gaddipati J, Srimal RC. Multiple biological activities of curcumin: a short review. Life Sci. 2006;78:2081–2087. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Funk JL, Frye JB, Oyarzo JN, Zhang H, Timmermann BN. Anti-arthritic effects and toxicity of the essential oils of turmeric (Curcuma longa L) J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:842–849. doi: 10.1021/jf9027206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Song W, Qiao X, Liang WF, Ji S, Yang L, Wang Y, et al. Efficient separation of curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin from turmeric using supercritical fluid chromatography: From analytical to preparative scale. J Sep Sci. 2015;38:3450–3453. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201500686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pulikkotil SJ, Nath S. Effects of curcumin on crevicular levels of il-1β and ccl28 in experimental gingivitis. Aust Dent J. 2015;60:317–327. doi: 10.1111/adj.12340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Waghmare PF, Chaudhari AU, Karhadkar VM, Jamkhande AS. Comparative evaluation of turmeric and chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash in prevention of plaque formation and gingivitis: a clinical and microbiological study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2011;12:221–224. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Farjana HN, Chandrasekaran SC, Gita B. Effect of oral curcuma gel in gingivitis management - a pilot study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:Zc08–10. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8784.5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Behal R, Gilda SS, Mali AM. Comparative evaluation of 01% turmeric mouthwash with 02% chlorhexidine gluconate in prevention of plaque and gingivitis: a clinical and microbiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:386–391. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.100917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.M Pascual, K Slowing, E Carretero DS, Mata A. Villar Lippia: traditional uses, chemistry and pharmacology: a review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;76:201–214. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rodrigues IS, Tavares VN, Pereira SL, Costa FN. Antiplaque and antigingivitis effect of Lippia sidoides: a double-blind clinical study in humans. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;17:404–407. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572009000500010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Botelho MA, dos Santos RA, Martins JG, Carvalho CO, Paz MC, Azenha C, et al. Comparative effect of an essential oil mouthrinse on plaque, gingivitis and salivary Streptococcus mutans levels: a double blind randomized study. Phytother Res. 2009;23:1214–1219. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Botelho MA, Bezerra Filho JG, Correa LL, Fonseca SG, Montenegro D, Gapski R, et al. Effect of a novel essential oil mouthrinse without alcohol on gingivitis: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial. J Appl Oral Sci. 2007;15:175–180. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572007000300005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shen CC, Ni CL, Shen YC, Huang YL, Kuo CH, Wu TS, et al. Phenolic constituents from the stem bark of Magnolia officinalis. J Nat Prod. 2008;72:168–171. doi: 10.1021/np800494e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu HH, Yang ZL, Sun B, Liu RN. Genetic diversity and relationship of endangered plant Magnolia officinalis (magnoliaceae) assessed with issr polymorphisms. Biochem Systemat Ecol. 2011;39:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Campus G, Cagetti MG, Cocco F, Sale S, Sacco G, Strohmenger L, et al. Effect of a sugar-free chewing gum containing magnolia bark extract on different variables related to caries and gingivitis: a randomized controlled intervention trial. Caries Res. 2011;45:393–399. doi: 10.1159/000330234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singh O, Khanam Z, Misra N, Srivastava MK. Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L): an overview. Pharmacog Rev. 2011;5:82–95. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.79103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975;25:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goes P, Dutra CS, Lisboa MRP, Gondim DV, Leitão R, Brito GAC, et al. Clinical efficacy of a 1% matricaria Chamomile L mouthwash and 012% chlorhexidine for gingivitis control in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. J Oral Sci. 2016;58:569–574. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.16-0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kiany F, Niknahad H, Niknahad M. Assessing the effect of pomegranate fruit seed extract mouthwash on dental plaque and gingival inflammation. J Dent Res Rev. 2016;3:117–123. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pandey G, Madhuri S. Pharmacological activities of Ocimum sanctum (tulsi): a review. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2010;5:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vieira RF, Simon JE. Chemical characterization of basil (ocimum spp) found in the markets and used in traditional medicine in brazil. Econ Bot. 2000;54:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pereira SL, Oliveira JW, Angelo KK, Costa AM, Costa F. Clinical effect of a mouth rinse containing Ocimum gratissimum on plaque and gingivitis control. J Contem Dent Prac. 2011;12:350–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gupta D, Bhaskar DJ, Gupta RK, Karim B, Jain A, Singh R, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of Ocimum sanctum and chlorhexidine mouthwash on dental plaque and gingival inflammation. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2014;5:109–116. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.131727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jafri M, Aslam M, Javed K, Singh S. Effect of Punica granatum Linn(flowers) on blood glucose level in normal and alloxan-induced diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;70:309–314. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jurenka JS. Therapeutic applications of pomegranate (Punica granatum L): a review. Altern Med Rev. 2008;13:128–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Menezes SM, Cordeiro LN, Viana GS. Punica granatum (pomegranate) extract is active against dental plaque. J Herb Pharmacother. 2006;6:79–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dalai DR, Tangade P, Punia H, Ghosh S, Singh N, Yogesh Garg Y. Evaluation of anti-gingivitis efficacy of Punica granatum mouthwash and 02% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash through a 4 day randomized controlled trial. Arch Dent Med Res. 2016;2:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 84.DiSilvestro RA, DiSilvestro DJ, DiSilvestro DJ. Pomegranate extract mouth rinsing effects on saliva measures relevant to gingivitis risk. Phytother Res. 2009;23:1123–1127. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nóbrega RM, Santos RL, Coelho Soares RS, Muniz Alves P, Medeiros ACD, Pereira JV. A randomized, controlled clinical trial on the clinical and microbiological efficacy of Punica granatum Linn mouthwash. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatria Clin Integr. 2015;15:301–308. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Salgado ADY, Maia JL, Pereira SLDS, De Lemos TLG, Mota OMDL. Antiplaque and antigingivitis effects of a gel containing punica granatum linn extract a double-blind clinical study in humans. J Appl Oral Sci. 2006;14:162–166. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572006000300003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sedigh-Rahimabadi M, Fani M, Rostami-Chijan M, Zarshenas MM, Shams M. A traditional mouthwash (Punica granatum var pleniflora) for controlling gingivitis of diabetic patients: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2017;22:59–67. doi: 10.1177/2156587216633370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Somu CA, Ravindra S, Ajith S, Ahamed MG. Efficacy of a herbal extract gel in the treatment of gingivitis: a clinical study. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2012;3:85–90. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.96525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Akhtar J, Siddique KM, Bi S, Mujeeb M. A review on phytochemical and pharmacological investigations of miswak (Salvadora persica Linn) J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3:113–117. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.76488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Halawany HS. A review on miswak (Salvadora persica) and its effect on various aspects of oral health. Saudi Dent J. 2012;24:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Amoian B, Moghadamnia AA, Barzi S, Sheykholeslami S, Rangiani A. Salvadora persica extract chewing gum and gingival health: improvement of gingival and probe-bleeding index. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2010;16:121–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Khalessi AM, Pack AR, Thomson WM, Tompkins GR. An in vivo study of the plaque control efficacy of Persica: a commercially available herbal mouthwash containing extracts of salvadora persica. Int Dent J. 2004;54:279–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Azaripour A, Mahmoodi B, Habibi E, Willershausen I, Schmidtmann I, Willershausen B. Effectiveness of a miswak extract-containing toothpaste on gingival inflammation: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Dent Hyg. 2017;15:195–202. doi: 10.1111/idh.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Haerian-Ardakani A, Rezaei M, Talebi-Ardakani M, Keshavarz Valian N, Amid R, Meimandi M, et al. Comparison of antimicrobial effects of three different mouthwashes. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:997–1003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Patel PV, Shruthi S, Kumar S. Clinical effect of miswak as an adjunct to tooth brushing on gingivitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:84–88. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.94611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.A Sofrata, F Brito, M Al-Otaibi, A Gustafsson. Short term clinical effect of active and inactive Salvadora persica miswak on dental plaque and gingivitis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:1130–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bajaj N, Tandon S. The effect of triphala and chlorhexidine mouthwash on dental plaque, gingival inflammation, and microbial growth. Intl J Ayurveda Res. 2011;2:29–36. doi: 10.4103/0974-7788.83188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Naiktari RS, Gaonkar P, Gurav AN, Khiste SV. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate and compare the efficacy of triphala mouthwash with 02% chlorhexidine in hospitalized patients with periodontal diseases. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2014;44:134–140. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2014.44.3.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chainani SH, Siddana S, Reddy C, Manjunathappa TH, Manjunath M, Rudraswamy S. Antiplaque and antigingivitis efficacy of triphala and chlorhexidine mouthrinse among schoolchildren - a cross-over, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2014;12:209–217. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a32674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gupta D, Bhaskar DJ, Gupta RK, Karim B, Gupta V, Punia H, et al. Effect of Terminalia chebula extract and chlorhexidine on salivary pH and periodontal health: 2 weeks randomized control trial. Phytother Res. 2014;28:992–998. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gupta D, Gupta RK, Bhaskar DJ, Gupta V. Comparative evaluation of Terminalia chebula extract mouthwash and chlorhexidine mouthwash on plaque and gingival inflammation - 4-week randomised control trial. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2015;13:5–12. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a32994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tangade PS, Mathur A, Tirth A, Kabasi S. Anti-gingivitis effects of Acacia arabica-containing toothpaste. Chin J Dent Res. 2012;15:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pradeep AR, Agarwal E, Naik SB. Clinical and microbiologic effects of commercially available dentifrice containing Aloe vera: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2012;83:797–804. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sharma R, Hebbal M, Ankola A, Murugaboopathy V, Shetty S. Effect of two herbal mouthwashes on gingival health of school children. J Tradit Complement Med. 2014;4:272–278. doi: 10.4103/2225-4110.131373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Makarem A, Khalili N, Asodeh R. Efficacy of barberry aqueous extracts dental gel on control of plaque and gingivitis. Acta Med Iran. 2007;45:91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Khosravi Samani M, Mahmoodian H, Moghadamnia AA, Poorsattar Bejeh Mir A, Chitsazan M. The effect of Frankincense in the treatment of moderate plaque-induced gingivitis: A double blinded randomized clinical trial. DARU J Pharm Sci. 2011;19:288–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Balappanavar A, Sardana V, Singh M. Comparison of the effectiveness of 05% tea, 2% neem and 02% chlorhexidine mouthwashes on oral health: A randomized control trial. Indian J Dent Res. 2013;24:26–34. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.114933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gupta D, Jain A. Effect of cinnamon extract and chlorhexidine gluconate (02%) on the clinical level of dental plaque and gingival health: a 4-week, triple-blind randomized controlled trial. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2015;17:91–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pereira SL, Barros CS, Salgado TD, Filho VP, Costa FN. Limited benefit of copaifera oil on gingivitis progression in humans. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2010;11:E057–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]