Abstract

Getting a good night’s sleep can be challenging for older adults with chronic medical conditions, which often interfere with sleep. As a result, many older adults turn to over-the-counter (OTC) sleep aids, that is, products with diphenhydramine or doxylamine. However, these products are indicated only for occasional difficulty with sleep, not for chronic use; and their safety and efficacy has not been well established in general and in older adults specifically. To engage national stakeholders in a discussion of OTC sleep aids in older adults, the Gerontological Society of America (GSA) convened a multidisciplinary workgroup. The Workgroup examined differences between younger and older adults in sleep health and use of OTC sleep aids using data from the National Health and Wellness Survey; assessed the pharmacologic properties and medication effects of OTC sleep aids; and worked with stakeholders to promote strategies for safe and effective use. Older adults are more likely to take diphenhydramine or doxylamine products 15 or more days in a month, an indicator of inappropriate use. The Workgroup recommends research to investigate the ways older people use OTC sleep aids. The goal should be reduction in inappropriate use and associated risks, such as daytime sedation, compromised cognitive function, and falls. In addition, the Workgroup recommends a greater role for community pharmacists in counseling older adults on appropriate use of OTC sleep aids.

Keywords: Sleep, Medications, OTC drugs, Pharmacology, Patient communication, Preventive medicine, Public policy

Getting a good night’s sleep can be challenging for older adults with chronic medical conditions or pain, which often interfere with sleep. As a result, many older adults and their caregivers turn to over-the-counter (OTC) sleep aids to promote sleep. However, these products are indicated only for occasional difficulty with sleep, not for chronic use; and their safety and efficacy has not been well established in general and in older adults specifically. In older adults, currently available OTC sleep aids may result in daytime sedation, compromised cognitive function, and falls and car crashes. They may also increase the risk of anticholinergic-related adverse events, such as blurred vision, constipation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and increased intraocular pressure.

To engage national stakeholders in a discussion of safe and effective use of OTC sleep aids in older adults, the Gerontological Society of America (GSA) convened a multidisciplinary workgroup and organized a series of national summits. The first summit took place in October 2013. It brought together experts from a number of fields to review data on sleep health and use of OTC sleep aids among older adults. The group recommended several policy initiatives to support sleep health in older adults and a multipronged effort to improve sleep health modeled on other successful public health campaigns. A follow-up national summit, convened by GSA in June 2014, opened the discussion to include stakeholders from a variety of professions involved in sleep health and aging, including psychologists, sleep medicine physicians, pharmacists, injury researchers, and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory staff.

Results from the OTC Sleep Aids Workgroup have appeared in a number of GSA publications: Sleep Health and the Appropriate Use of OTC Sleep Aids in Older Adults (GSA, 2013), Sleep Health and the Appropriate Use of OTC Sleep Aids in Older Adults: Update (GSA, 2014), and Spotlight on OTC Sleep Aids and Sleep Health in Older Adults (2013) in the What’s Hot series. GSA also sponsored two webinars to disseminate Workgroup efforts.

In this Forum contribution, we build on these efforts to examine the challenges posed by OTC sleep aid use among older adults. We focus on three key issues: (a) What is different about sleep disturbance and OTC sleep aid use among older and younger adults? (b) What is different about the activity of OTC sleep aids in older and younger adults? And (c) given such differences, what kinds of education or policy changes would increase safe and effective use of OTC sleep aids among older adults?

Sleep Disturbance among Older Adults

While sleep is a biological imperative, the optimal amount of sleep varies by age group (ranging from over 15hr/day for infants to about 7–8 in old age). Even within age groups, there is variability in need for sleep. Overall, Americans get less sleep than they need. Data from polls conducted by the National Sleep Foundation (NSF) show that Americans sleep an average of 6hr and 31min each night, about an hour less than the mean of 7hr and 13min they admit they need to function at their best (National Sleep Foundation, 2013). NSF has recently published recommendations for the appropriate amount of sleep time at different ages (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015). The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has also developed recommendations, which are still under discussion.

Sleep may be disturbed for a variety of reasons, including extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Extrinsic factors include a decrease in periodic environmental stimuli (e.g., exposure to sunlight), inactivity, and ambient factors such as excessive noise and light during the sleep period, as well as self-imposed sleep restriction. In hospital and institutional settings, nursing care activities throughout the night can disrupt sleep. Intrinsic factors include medical conditions and associated symptoms, such as pain, as well as medications used to manage these conditions. Other intrinsic factors include alterations in the internal circadian clock and increases in the prevalence of primary sleep disorders, such as narcolepsy, various parasomnias, and sleep-disordered breathing/sleep apnea.

Insomnia should be distinguished from sleep disturbance. “Insomnia” is a disorder defined by (a) having difficulty sleeping (difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, or not feeling rested after sleeping), (b) which occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstance for sleep, (c) which is associated with daytime impairment or distress, and (d) which occurs at least three times per week for at least 1 month (Roth, 2007). DSM-V further distinguishes between “chronic insomnia” for this level of sleep problems lasting 3 months or longer and “short-term insomnia” of less than 3 months. “Sleep disturbance,” by contrast, is difficulty sleeping one to two nights in a week over 2 weeks and is not specific. It can be the result of an acute event (such as injury or jet lag) or a symptom of other sleep disorders. OTC sleep aids are indicated for sleep disturbance (“occasional sleeplessness”), not insomnia. A major challenge in investigating sleep health and OTC sleep aids is confusion between insomnia and sleep disturbance. Unfortunately, surveys of sleep health do not typically distinguish between the two.

Population-based estimates of the prevalence of “sleep disturbance” in the United States by age and gender are available in the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS) sleep module. Sleep disturbance in the BRFSS is elicited by asking, “Over the last 2 weeks, how many days have you had trouble falling asleep or staying asleep or sleeping too much?” Dichotomizing results to identify respondents reporting a complaint <6 or ≥6 days in a 2-week period reveals an overall decline in acute sleep disturbance at older ages (Grandner et al., 2012). For example, among women aged 18–64, 20%–25% met the criterion for sleep disturbance. At ages 65 or older, the proportion drops below 20% and is lowest among women aged 80+, with only 17.7% reporting sleep disturbance. A smaller proportion of men report sleep disturbance at every age, and by age 80+ only 15.4% report sleep disturbance. Independent correlates of sleep disturbance identified in the BRFSS include nonwhite race/ethnicity, poorer self-rated health, and depressed mood. Note that this measure does not distinguish insomnia from sleep disturbance. The 2-week window of the question makes it difficult to distinguish the two, each of which may have different correlates. Separating sleep disturbance and insomnia may give a different picture of the age-related prevalence of sleep problems.

The BRFSS finding of declining sleep disturbance with greater age should be interpreted with a number of caveats. First, the nature and chronicity of sleep disturbance may vary with age. One study found older adults more likely to report early morning awakenings and daytime sleepiness than younger adults (Soldatos, Allaert, Ohta, & Dikeos, 2005). Second, reports of less sleep disturbance in old age stand in contrast to declines in many objective sleep parameters, such as total sleep time and slow-wave sleep, as indicated by polysomnography (Ohayon, Carskadon, Guilleminault, & Vitiello, 2004). Thus, response bias may be at work, with older adults using different standards for adequate sleep than younger adults. They may have an expectancy of age-related declines in sleep quality and hence may be less likely to report sleep problems. Third, older adults face fewer of the life stressors that affect sleep, such as childbearing and work, are more likely to be retired, and are less likely to use technologies associated with interruption of sleep, such as electronics in the bedroom. Societal and cohort factors may thus play a role, along with socioeconomic status (Patel, Grandner, Xie, Branas, & Gooneratne, 2010). Finally, the BRFSS relies on telephone interviews of people residing in the community and thus necessarily excludes older people in poorest health, who are less likely to participate in surveys and more likely to reside in skilled care facilities.

Research with older people suggests that older adults without medical or psychiatric problems are less likely to exhibit sleep problems and that sleep disturbance is not a normal part of aging (Vitiello, Moe, & Prinz, 2002). Healthy older adults experience much less sleep disturbance than those with multimorbidity (Ohayon et al., 2004). In general, the more chronic medical conditions and the greater their severity, the worse people sleep (Zee & Turek, 2006). Diseases associated with poor sleep include diabetes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases, mood disorders, cognitive decline, pain conditions, and neurologic disorders (McCurry, Logsdon, Teri, & Vitiello, 2007). Recent research also suggests a bidirectional relationship between sleep loss and certain conditions, such as dementia, pain conditions, and depression. For example, sleep loss increases amyloid-β in the brain and its accumulation has been associated with Alzheimer’s disease. With increasing amyloid-β, we see increased wakefulness and altered sleep patterns (Ju, Lucey, & Holtzman, 2014).

In older adults, the effects of poor sleep extend over many domains. Documented impacts of poor sleep in older adults include difficulty sustaining attention, slowed response time, and impairments in memory and concentration (Cricco, Simonsick, & Foley, 2001); decreased ability to accomplish daily tasks (Ancoli-Israel & Cooke, 2005); increased risk of falls (Stone et al., 2008), inability to enjoy social relationships; increased incidence of pain and reduced quality of life (Léger, Scheuermaier, Philip, Paillard, & Guilleminault, 2001); risk of traffic accidents (American Automobile Association, 2014), increased consumption of health care resources (Hajak et al., 2011); and shorter survival (Dew et al., 2003).

Despite this pervasive impact of sleep on health and well-being, sleep difficulties in older adults are under-recognized in medical practice and therefore undertreated. One survey found that adults who reported insomnia were unlikely to discuss it with their health care provider (Ancoli-Israel & Roth, 1999). Only 5% of respondents said that insomnia was a primary reason for visiting a health care provider, and 26% said it was a secondary reason. Fully 69% of respondents never discussed their sleep disturbances with a health care provider. These data point to the need for health care providers to be more proactive about gathering information about their patients’ sleep health and efforts at treatment, including, when appropriate, use of OTC sleep aids.

OTC Sleep Aids and Strategies for Addressing Sleep Disturbance

Available OTC sleep aids all include diphenhydramine or doxylamine, “first-generation antihistamines” approved by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) alone or in combination with other products, such as OTC analgesics. Diphenhydramine is found in the majority of products under a variety of brand names, including Nytol, Sominex, Tylenol PM, Excedrin PM, Advil PM, Unisom SleepGels, and ZzzQuil. Doxylamine is found in Unisom SleepTabs, Equaline Sleep Aid, and Good Sense Sleep Aid. Other products, such as Benadryl and a variety of pain relief-sleep combinations also contain diphenhydramine. Although the agents are indicated only for treatment of occasional sleeplessness, several lines of evidence assessed by the Workgroup suggest that a subset of older adults may use them chronically to treat insomnia or as part of routine self-care.

Beyond FDA-approved therapies, several dietary supplements, including valerian, tryptophan, and melatonin, are used as sleep aids. In general, evidence to support their use is lacking and questions remain about their safety, especially when used chronically (Ramakrishnan & Scheid, 2007). Unlike OTC and prescription products, dietary supplements receive virtually no scrutiny from the FDA.

Other common strategies to address sleep disturbance include alcohol use, a behavior that unfortunately disrupts sleep and interacts with sleep-promoting agents. Up to 28% of patients report using alcohol to promote sleep (Johnson, Roehrs, Roth, & Breslau, 1998). Although alcohol may reduce sleep-onset latency, it is not recommended as a sleep aid because alcohol fragments sleep in the second part of the night and can increase daytime sleepiness and promote future sleep disturbances.

Evidence suggests that nonpharmacological treatments for chronic insomnia, such as cognitive behavioral therapies, relaxation techniques, or exercise, are effective in older adults. However, more research is needed on the efficacy of nonpharmacologic treatments for occasional sleep disturbance, as opposed to chronic insomnia, to determine if these approaches are also effective in older and younger adults with acute sleep disturbances.

Use of OTC Sleep Aids by Older Adults

Few data are available on use of OTC sleep aids. One study suggests that 10% of adults aged 18–45 years use OTC sleep aids. The majority (70%) of these individuals used the products for less than 1 week at a time, and the overwhelming majority (84%) used the products less than a total of 30 times in a year. However, 9% of individuals used the products for 4 weeks or more, and 3% had used them 180 times or more in the past year (Johnson et al., 1998).

To examine differences between younger and older adults in sleep health and use of OTC sleep aids, the workgroup analyzed cross-sectional data from the National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS), an Internet-based, Institutional Review Board-approved health survey of adults aged 18 years and older. A total of 75,000 adults participated in the 2013 wave of the survey, which is weighted to reflect the total U.S. adult population aged 18+ of 223.8 million (Kantar Health, 2013, 2014). The NHWS Internet panel recruits participants through opt-in e-mails, co-registration with other panels, e-newsletters, and online banner placements. Panel members are limited in the number of annual surveys they complete and receive points that can be exchanged for prizes. Invitations to participate in the NHWS use random stratified sampling to ensure that NHWS participants are representative of the adult population in the United States. The NHWS has been used in a number of studies assessing health behavior (DiBonaventura, Wintfeld, Huang, & Goren, 2014; Goren, Annunziata, Schnoll, & Suaya, 2014).

Participants in the NHWS reported their experience regarding sleep, including “symptoms of sleeplessness,” and whether they experience or have been diagnosed with “insomnia” or “sleep difficulties.” The survey also asked participants whether they had primary sleep disorders, such as narcolepsy, various parasomnias, sleep-disordered breathing/sleep apnea, and/or various circadian rhythm disorders. People reporting such primary sleep disorders were excluded from these analyses.

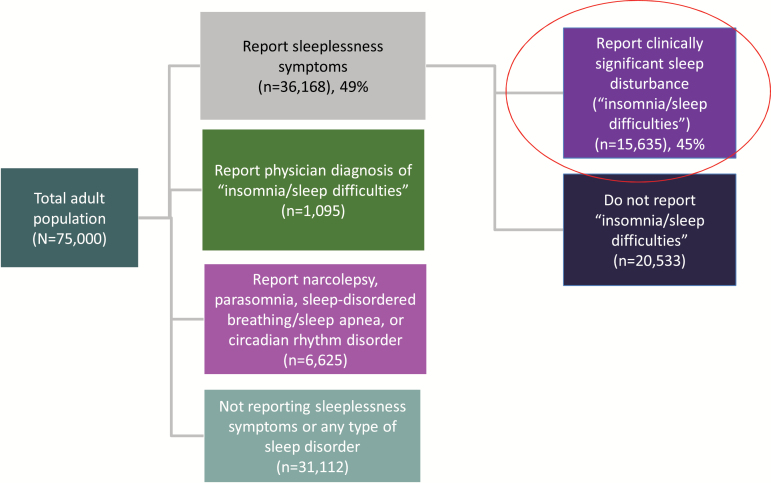

Results from the NHWS for the U.S. adult population aged 18+ are shown in Figure 1. Approximately 49% of the participants in the NHWS reported that they experienced at least some symptoms of sleeplessness in the past 12 months. An additional 2% of the surveyed population did not report regularly experiencing these symptoms but did report experiencing insomnia/sleep difficulties. Extrapolating to the population aged 18+, 115 million individuals in the United States experience symptoms of sleeplessness each year, and an additional 3.8 million report insomnia/sleep difficulties. To establish the prevalence of sleeplessness with functional consequences, Figure 1 presents information for the group reporting sleeplessness that also reported insomnia/sleep difficulties as one of their symptoms. Extrapolating to the U.S. population, 51.2 million Americans, about 21.9%, report this level of sleep disturbance.

Figure 1.

National Health and Wellness Survey: Sleep Medication Sub-Study.

Among the 41.3 million adults aged 65+, 6.3 million report sleeplessness with insomnia/sleep difficulties, or 15.3%. Of the 6.3 million, 1.1 million used an OTC sleep aid, 17.5% of people with symptoms, and 2.7% of the total older adult population (Gross, O’Neill, Toscani, & Chapnick, 2015).

Younger and older adults differed to some degree in reports of sleeplessness in the past 12 months, as shown in Table 1. Among those with any sleep symptom and also reporting insomnia/sleep difficulties, the groups differed in reports of difficulty falling asleep (74% aged 18–64, 65% aged 65–74, and 62% aged 75+) and waking during the night (52% aged 18–64, 63% aged 65–74, and 63% aged 75+), but not in waking up too early (41% aged 18–64, 39% aged 65–74, and 38% aged 75+). The groups also differed in reports of poor quality sleep, with older adults less likely to report poor quality sleep: 48% aged 18–64, 28% aged 65–74, and 26% aged 75+.

Table 1.

Differences by Age among People Reporting Symptoms of Sleeplessness and Insomnia or Sleep Difficulties in Past 12 Months, Weighted for U.S. Population

| Age | Pairwise significance tests (p < .05) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–64 | 65–74 | 75+ | ||

| Any report of sleeplessness and insomnia or sleep difficulties, % | 23 | 16 | 14 | 18–64 > 65–74 > 75+ |

| Of people reporting sleeplessness and insomnia or sleep difficulties: | ||||

| Difficulty falling asleep, % | 74 | 65 | 62 | 18–64 > 65–74 and 75+ |

| Waking during the night, % | 52 | 63 | 63 | 18–64 < 65–74 and 75+ |

| Waking up too early, % | 41 | 39 | 38 | N.S. |

| Poor quality sleep, % | 48 | 28 | 26 | 18–64 > 65–74 and 75+ |

| Use of concomitant anticholinergic medication, % | 23 | 33 | 44 | 18–64 < 65–74 and 75+ |

| Use of alcohol, % | 76 | 65 | 54 | 18–64 > 65–74 > 75+ |

| 15+ days per month using diphenhydramine or doxylamine products, % | 21 | 37 | 47 | 18–64 < 65–74 and 75+ |

Young and old individuals did not differ in OTC or herbal strategies to alleviate sleep problems. In all age groups about half used a prescription, OTC sleep aid, or herbal product. Among those with any sleep symptom and also reporting insomnia/sleep difficulties, about 18% in all three age groups reported use of an OTC sleep aid, and about a third of these reported an OTC product or a supplement. The most commonly used product was an herbal supplement, melatonin, followed by “Tylenol products” (which may contain diphenhydramine), and “Benadryl/diphenhydramine.” Among older adults with insomnia/sleep difficulties, the most commonly used prescription sleep aid was zolpidem (Ambien), followed by trazodone hydrochloride (Trazodone, an off-label use) and alprazolam (Xanax, also off-label).

While younger and older adults did not differ in reported sleep difficulties or recourse to OTC products, the workgroup was surprised to find major differences in the way the different age groups use OTC sleep aids. Product labeling for diphenhydramine and doxylamine advises patients to stop use and consult a heath care provider if sleeplessness persists for more than 2 weeks. However, a large number of older adults use the medications chronically. Among people taking OTC sleep aids, 21% of people aged 18–64, 37% of people aged 65–74, and 47% of people aged 75+ reported 15+ days use in the prior month. Use of the products for 15 days or more in the past month is considered inappropriate, given that the drug facts label suggests no more than 2 weeks use in a month. Older adults using OTC sleep aids were also more likely to be taking concomitant anticholinergic medications (23%, aged 18–64; 33%, aged 65–74; and 44%, aged 75+) but less likely to use alcohol (76%, aged 18–64; 65%, aged 65–74; and 54%, aged 75+). Still, even this level of alcohol use is a concern, because drug fact labels for diphenhydramine and doxylamine recommend avoiding alcohol while using the products.

Differences in OTC Medication Effects in Younger and Older Adults

Pharmacokinetics of OTC Sleep Aids

Data describing the pharmacokinetics of OTC sleep aids are scarce. Available data are limited to diphenhydramine. Because older adults may have slower metabolism and clearance than younger adults, medication half-lives tend to be prolonged, and peak concentrations tend to be higher in older adults. Data suggest this is the case for diphenhydramine as well. An early study reported that diphenhydramine has a half-life of 9.2hr in adults (mean age 31.5 years), rising to 13.5hr in elderly adults (mean age 69.4 years) (Simons, Watson, Martin, Chen, & Simons, 1990). However, another study found the half-life to range from 4.1hr in young adults to 7.4hr in older adults (Scavone, Greenblatt, Harmatz, Engelhardt, & Shader, 1998). A review published in 1986 found a reported half-life range for diphenhydramine from 3.3 to 9.3hr (Blyden, Greenblatt, Scavone, & Shader, 1986).

It is important to note that these studies were published in the 1980s and 1990s and did not employ techniques used to establish pharmacokinetic parameters accepted today. Therefore, the actual half-life of these products remains unclear. However, these limited data suggest that some older individuals may be subject to circulating diphenhydramine when they awaken in the morning, which could cause sedation, compromised cognitive function, dizziness, or falls. Additional data evaluating the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of diphenhydramine and doxylamine are needed, especially in older adults. In particular, age, sex, and food effects need to be studied in the older population taking the medications, as well as the potential effects of accumulation on cognition, falls, and activities such as driving.

Efficacy and Safety of OTC Sleep Aid Use

Decades of use of first-generation antihistamines for the treatment of allergic disorders demonstrate that these agents are sedating. In fact, these agents are often referred to as “sedating antihistamines.” However, whether this effect translates into efficacy for treating occasional sleeplessness or chronic insomnia remains unclear. Because diphenhydramine and doxylamine were marketed before the FDA began the OTC drug monograph process in 1972, the drugs were “grandfathered” and not subject to the same requirements for randomized placebo-controlled trials that are required today for drugs going through a New Drug Application approval process (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2014).

Similarly, the risks and benefits of OTC sleep aids for the treatment of disturbed sleep in elderly adults have not been systematically examined in randomized controlled trials. There are no published controlled trials examining the use of doxylamine for the treatment of sleeplessness. Small controlled trials of diphenhydramine 50mg are available but the results are equivocal. The most positive published trial supporting the use of diphenhydramine as a sleep aid found that diphenhydramine 50mg significantly improved patient reports of disturbed sleep, including sleep latency and reports of feeling more rested the following morning. Patients in the trial also reported that they preferred diphenhydramine to placebo despite experiencing more side effects (Rickels et al., 1983). Other published data using both patient reports and objective measures of sleep, however, are less positive (Morin, Koetter, Bastien, Ware, & Wooten, 2005). This limited efficacy should be considered in light of the negative residual and anticholinergic side effects associated with diphenhydramine use. For example, in a nursing home population, diphenhydramine was associated with significant psychomotor and cognitive function impairments compared with placebo (Meuleman, Nelson, & Clark, 1987). While diphenhydramine improved sleep latency relative to placebo, there were no other significant benefits.

Additional concerns about the use of diphenhydramine concern anticholinergic effects. Anticholinergic effects include blurred vision, constipation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and risk of increased intraocular pressure in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma. According to the Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults, first-generation antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine, should generally be avoided in older adults due to anticholinergic activity (American Geriatrics Society, 2012).

Intervening to Address Sleep Disturbance and OTC Sleep Aids: Key Role of Pharmacy Professionals

The workgroup singled out pharmacists as being uniquely positioned to provide education to older adults about OTC sleep aids. They may be the only health care providers who interact with patients regarding these OTC purchases. While consumers can purchase OTC sleep aids without consulting pharmacists, greater involvement of pharmacists at the point of sale may reduce unintentional misuse.

One promising approach to enlist pharmacists in this effort is a series of web-based modules to alert pharmacists to the challenges of OTC sleep aid use among older adults. GSA has engaged Silver Market Training Modules (http://prod.geron.org/Resources/silver-market-training-modules) to develop tools to help pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and possibly other health care professionals work with older adults. The workgroup helped Silver Market develop two 25-min modules involving realistic case studies. The modules include pre- and posttests. One module addresses sleep health in old age (Sleep Health in Older Adults) and the other challenges associated with OTC sleep aids (Non-Prescription Sleep Aid Use in Older Adults). Case studies demonstrate how to address common challenges for older adults with sleep health issues. For example, the latter module features an older adult (The Worried Well), who reports she is “not sleeping as well as I used to” but upon questioning reveals her nighttime sleep is age-appropriate and daytime function is undisturbed. In Acute Sleep Disturbance, a patient with a clear precipitating factor (recent bereavement), experiences disturbed sleep, and Chronic Insomnia features a patient with frank sleep maintenance insomnia. Pharmacists are counseled to discourage OTC for the first, to consider short-term OTC in consultation with another health care provider for the second, and to refer the third to a health care provider for possible prescription medication.

Pharmacists are also guided to interview patients considering use of OTC products. In the case of a patient purchasing or asking for an OTC sleep aid, the pharmacy professional queries the patient about sleep hygiene practices, the nature and duration of the sleep disturbance and other current medication use, both prescription and OTC, including supplements, along with use of alcohol. For the patient considering an OTC sleep aid with known anticholinergic side effects, the pharmacy professional queries the patient about prescription and OTC products with anticholinergic properties that the patient may already be taking.

Advocacy for Sleep Health and the Safe and Effective Use of OTC Sleep Aids

A key challenge for advocates is to ensure that an issue becomes part of a larger, preferably national conversation. A crucial first step for influencing policy is to identify primary and secondary audiences for the issue. The primary audience for advocacy efforts is composed of decision makers with authority to modify or introduce policies (i.e., Congress). Secondary audiences include individuals or groups that can influence decision makers. These audiences include advisors, foundations, professional societies, patient groups, industry, and media. Once audiences are identified, advocates can work to disseminate their messages to these groups.

To reach the primary audience, the workgroup presented information on sleep health and OTC sleep aids in November 2014 in a congressional hill briefing sponsored by Senator Bill Nelson, Chairman of the U.S. Senate Aging Committee. To address secondary audiences, summit invitees included representatives from the American Society of Consultant Pharmacists, the National Sleep Foundation, the National Council on Patient Information and Education, the American Psychological Association, the National Council on Aging, the Consumer Healthcare Products Association, the FDA, the American Pharmacists Association, American Automobile Association, National Council on Aging, National Hispanic Aging Council, NIH, and CDC. Finally, the two webinars attracted some 100 participants each from a variety of educational and consumer organizations. Twitter activity extended the reach of these activities.

Conclusions

The GSA workgroup on Sleep Health and Appropriate Use of OTC Sleep Aids in Older Adults addressed three questions. The first was “What is different about sleep disturbance and OTC sleep aid use among older adults relative to younger adults?” Our investigation suggests that older adults are not very different from younger adults in the prevalence of sleep disturbance or recourse to OTC medications. Differences between age groups are subtle. For reasons still unclear, older adults use OTC products differently. They are about twice as likely to take them 15 or more days per month, as mentioned earlier, a conservative criterion for inappropriate use. Is this because they are using OTC products to treat chronic insomnia rather than more mild occasional sleep disturbance? If so, why are they not diagnosed with chronic insomnia and receiving appropriate prescription or behavioral therapy? Or, if not insomnia, why the excessive use? Is it because they are taking OTC sleep aids mainly to treat other symptoms, such as pain, or perceive them to be safe to use? Is the impact of drug tolerance a possibility? Or is the misuse unintentional and simply a byproduct of excessive use of many OTC and prescription products? Research to investigate the ways older people use OTC products would shed light on this issue and may suggest ways to reduce inappropriate use among older people, a key goal given concomitant use of medications with anticholinergic effects.

Our second question was “What is different about the activity of OTC sleep aids in older and younger adults?” Here we are hampered by the absence of current pharmacokinetic studies and limited randomized controlled trials. Still, available evidence suggests the potential for extended exposure due to longer half-lives for diphenhydramine in older people and the potential risk for hangover or next day effects that may increase the risk of falls and impaired neurocognitive function.

Finally, we asked, “Given such differences, what kinds of education or policy changes would increase safe and effective use of OTC sleep aids among older adults?” The workgroup singled out the pharmacy community as a key player in reducing inappropriate use and promoting safer use of OTC sleep aids. Taking a detailed sleep aid history and using medication profiles from pharmacy data should be consulted. In addition, educational materials will go some way in helping pharmacy professionals and others work with older adults to choose OTC sleep aids wisely. A bigger challenge will be to reconfigure the community pharmacy to support greater consultation with patients and consumers by pharmacists. Workgroup efforts have begun to promote a national dialogue on ways to promote sleep hygiene and reduce inappropriate use of OTC sleep aids and in this way reduce morbidity that may be associated with current products. Newer and more studied treatments, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic, are needed to promote better sleep health and outcomes in older adults with sleep disturbances.

Acknowledgments

This white paper was sponsored by Pfizer as part of a collaboration with the Gerontological Society of America (GSA) to support GSA’s campaign to address OTC sleep aids and sleep health in older adults. While Pfizer reviewed this paper and provided input, the authors retained full editorial control over the final content. Thanks to Hillary Gross from Kantar Health, who assisted in design and analysis of the NHWS survey data.

References

- American Automobile Association. (2014). Understanding older drivers: An examination of medical conditions, medication use, and travel behavior. Foundation for Traffic Safety. Washington DC: AAA Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- American Geriatrics Society. (2012). Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 60, 616–631. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancoli-Israel S., Cooke J. R. (2005). Prevalence and comorbidity of insomnia and effect on functioning in elderly populations. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(7 Suppl), S264–S271. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53392.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancoli-Israel S., Roth T. (1999). Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: Results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey. Sleep, 22(Suppl. 2):S347–S353. PMID: 10394606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyden G. T. Greenblatt D. J. Scavone J. M., & Shader R.I (1986). Pharmacokinetics of diphenhydramine and a demethylated metabolite following intravenous and oral administration. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 26, 529–533. doi:10.1002/j.1552–4604.1986.tb02946.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBonaventura M., Wintfeld N., Huang J., Goren A. (2014). The association between nonadherence and glycated hemoglobin among type 2 diabetes patients using basal insulin analogs. Patient Preference and Adherence, 8, 873–882. doi:10.2147/PPA.S55550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cricco M. Simonsick E. M., & Foley D. J (2001). The impact of insomnia on cognitive functioning in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 49, 1185–1189. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dew M. A. Hoch C. C. Buysse D. J. Monk T. H. Begley A. E. Houck P. R,…Reynolds C. F (2003). Healthy older adults’ sleep predicts all-cause mortality at 4 to 19 years of follow-up. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 63–73. PMID: 12554816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerontological Society of America. (2013). Sleep Health and the Appropriate Use of OTC Sleep Aids in Older Adults: White Paper/2014 Update Gerontological Society of America (in Collaboration with Pfizer), 2014. Retrieved from https://www.geron.org/programs-services/alliances-and-multi-stakeholder-collaborations/otc-medications-older-adults/otc-sleep-aids-and-sleep-health-of-older-adults [Google Scholar]

- Gerontological Society of America. (2014). What’s Hot: Spotlight OTC Sleep Aids and Sleep Health in Older Adults Retrieved from https://www.geron.org/programs-services/alliances-and-multi-stakeholder-collaborations/otc-medications-older-adults/otc-sleep-aids-and-sleep-health-of-older-adults

- Goren A., Annunziata K., Schnoll R. A., Suaya J. A. (2014). Smoking cessation and attempted cessation among adults in the United States. PLoS One, 9, e93014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner M. A. Martin J. L. Patel N. P. Jackson N. J. Gehrman P. R. Pien G.,…Gooneratne N. S (2012). Age and sleep disturbances among American men and women: Data from the U.S. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Sleep, 35, 395–406. doi:10.5665/sleep.1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross H. J O’Neill G. Toscani M., & Chapnick J (2015). Sex differences in over-the-counter sleep aid use in older adults. ISPOR 20th Annual International Meeting. Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- Hajak G. Petukhova M. Lakoma M. D. Coulouvrat C. Roth T. Sampson N. A.,…Kessler R. C (2011). Days-out-of-role associated with insomnia and comorbid conditions in the America Insomnia Survey. Biological Psychiatry, 70, 1063–1073. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshkowitz M. Whiton K. Albert S. M. Alessi C. Bruni O. DonCarlos,…Hillard P. J. A (2015). National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health, 1, 40–43. doi:org/10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. O. Roehrs T. Roth T., & Breslau N (1998). Epidemiology of alcohol and medication as aids to sleep in early adulthood. Sleep, 21, 178–186. PMID: 9542801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju Y. E., Lucey B. P., Holtzman D. M. (2014). Sleep and Alzheimer disease pathology–a bidirectional relationship. Nature Reviews. Neurology, 10, 115–119. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2013.269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantar Health. (2013). National Health and Wellness Survey: US. New York: Kantar Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kantar Health. (2014). The National Health and Wellness Survey: fact sheet. Retrieved from http://www.kantarhealth.com/docs/datasheets/Kantar_Health_NHWS_datasheet%20.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Léger D. Scheuermaier K. Philip P. Paillard M., & Guilleminault C (2001). SF-36: evaluation of quality of life in severe and mild insomniacs compared with good sleepers. Psychosomatic Medicine, 63, 49–55. PMID: 11211064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCurry S. M., Logsdon R. G., Teri L., Vitiello M. V. (2007). Sleep disturbances in caregivers of persons with dementia: contributing factors and treatment implications. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 11, 143–153. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman J.R. Nelson R.C., & Clark R.L. Jr (1987). Evaluation of temazepam and diphenhydramine as hypnotics in a nursing-home population. Drug Intelligence and Clinical Pharmacy, 21, 716–720. PMID: 2888637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin C. M. Koetter U. Bastien C. Ware J. C., & Wooten V (2005). Valerian-hops combination and diphenhydramine for treating insomnia: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Sleep, 28, 1465–1471. PMID: 16335333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Sleep Foundation. (2013). International Bedroom Poll: Summary of Findings Retrieved from http://sleepfoundation.org/sites/default/files/RPT495a.pdf

- Ohayon M. M. Carskadon M.A. Guilleminault C., & Vitiello M. V (2004). Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep, 27, 1255–1273. PMID: 15586779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel N. P., Grandner M. A., Xie D., Branas C. C., Gooneratne N. (2010). “Sleep disparity” in the population: poor sleep quality is strongly associated with poverty and ethnicity. BMC Public Health, 10, 475. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan K., & Scheid D. C. Treatment options for insomnia. (2007). American Family Physician, 76, 517–526. PMID: 17853625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickels K. Morris R. J. Newman H. Rosenfeld H. Schiller H., & Weinstock R (1983). Diphenhydramine in insomniac family practice patients: a double-blind study. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 23, 234–242. doi:10.1002/j.1552–4604.1983.tb02730.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth, T. (2007). Introduction-Advances in our understanding of insomnia and its management. Sleep Medicine, 8, S25–S26. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2007.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scavone J. M. Greenblatt D. J. Harmatz J. S. Engelhardt N., & Shader R. I (1998). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of diphenhydramine 25mg in young and elderly volunteers. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 38: 603–609. doi:10.1002/j.1552–4604.1998.tb04466.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K. J. Watson W. T. Martin T. J. Chen X. Y., & Simons F. E (1990). Diphenhydramine: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in elderly adults, young adults, and children. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 30, 665–671. doi:10.1002/j.1552–4604.1990.tb01871.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldatos C. R., Allaert F. A., Ohta T., Dikeos D. G. (2005). How do individuals sleep around the world? Results from a single-day survey in ten countries. Sleep Medicine, 6, 5–13. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2004.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone K. L. Ancoli-Israel S. Blackwell T. Ensrud K. E. Cauley J. A. Redline S.,…Cummings S. R (2008). Actigraphy-measured sleep characteristics and risk of falls in older women. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168, 1768–1775. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.16.1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2014). Development and regulation of OTC (nonprescription) drug products. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ucm209647.htm

- Vitiello M. V. Moe K. E., & Prinz P. N (2002). Sleep complaints cosegregate with illness in older adults: Clinical research informed by and informing epidemiological studies of sleep. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 555–559. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00435-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zee P. C., Turek F. W. (2006). Sleep and health: Everywhere and in both directions. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 1686–1688. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.16.1686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]