Abstract

Background. Over half of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections in the United States occur among men who have sex with men (MSM). Among MSM, 16% of estimated new infections in 2010 occurred among black MSM <25 years old.

Methodology. We analyzed National HIV Behavioral Surveillance data on MSM from 20 cities. Poisson models were used to test racial disparities, by age, in HIV prevalence, HIV awareness, and sex behaviors among MSM in 2014. Data from 2008, 2011, and 2014 were used to examine how racial/ethnic disparities changed across time.

Results. While black MSM did not report greater sexual risk than other MSM, they were most likely to be infected with HIV and least likely to know it. Among black MSM aged 18–24 years tested in 2014, 26% were HIV positive. Among white MSM aged 18–24 years tested in 2014, 3% were HIV positive. The disparity in HIV prevalence between black and white MSM increased from 2008 to 2014, especially among young MSM.

Conclusions. Disparities in HIV prevalence between black and white MSM continue to increase. Black MSM may be infected with HIV at younger ages than other MSM and may benefit from prevention efforts that address the needs of younger men.

Keywords: HIV, MSM, health disparities, black MSM

Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM), especially young black or African American (hereafter referred to as “black”) MSM, are at increased risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that the number of incident HIV infections increased 12% among MSM from 2008 to 2010 [1]. Of the 47 500 estimated incident HIV infections in 2010 in the United States, 63% were attributable to male-to-male sexual contact [1]. In 2010, black MSM accounted for 36% of all estimated incident HIV infections attributed to male-to-male sexual contact [1]; young black MSM aged 13–24 years accounted for 45% of the estimated incident HIV infections among black MSM and 16% of estimated incident HIV infections among all MSM [1]. Young, white MSM, on the other hand, accounted for 16% of the estimated incident HIV infections among white MSM in 2010 [1].

The reasons for these disparities are still unclear, but there is growing consensus that black MSM report lower sexual and drug-related risk behaviors and higher HIV testing than MSM of other races and ethnicities [2, 3]. There are a number of hypotheses that have been proposed to explain these disparities. Black MSM have higher reports of structural barriers that may increase HIV infection risk, such as unemployment, low income, previous incarceration, and less education [2]. Black MSM are more likely to report black sex partners and consequently have a higher HIV prevalence and transmission potential in their partner pool [4, 5]. Black MSM are less likely to be aware of their HIV-positive status and, therefore, less likely to access HIV treatment or be aware of the risk of transmitting HIV to others. HIV-positive black MSM are also less likely to initiate antiretroviral therapy (ART), to have health insurance, to have a high CD4+ T-cell count, to adhere to ART, or to be virally suppressed, compared with other MSM [2, 6].

This analysis complements previous work by assessing age-specific racial disparities among MSM in HIV prevalence, awareness of infection, and risk behavior in 2014 and by documenting changes from 2008 to 2014. We used data from MSM interviewed in 20 US cities during 2008, 2011, and 2014 as part of the CDC's National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS). Understanding racial disparities and how they change over time provides important indicators for the effectiveness of prevention efforts and insight into where future efforts should be concentrated. The National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS) [7, 8] places strong emphasis on reducing HIV-related disparities by directing interventions to communities at high risk for HIV infection, especially black Americans and MSM. The NHAS updated through 2020 [8] specifically identifies young MSM and young black MSM as important high-risk groups and specifies prevention goals for each. Prior NHBS analyses of 2008 and 2011 data have presented HIV prevalence, awareness, and risk behaviors by age or by race/ethnicity separately [9]; however, the emerging epidemic among young black MSM necessitates more-granular analysis to better understand racial disparities by age.

METHODS

NHBS was initiated in 2003 to monitor HIV-associated behaviors by conducting surveys in populations at high risk of HIV infection, including MSM [10]. NHBS provides data to monitor HIV prevalence overall and among subgroups, such as race/ethnicity and age, and to examine changes over time. NHBS staff in 20 metropolitan statistical areas (referred to as “cities” hereafter) with a high burden of AIDS collected cross-sectional behavioral data and conducted HIV testing among MSM in 2008, 2011, and 2014, using venue-based, time-space sampling (VBS) [11, 12]. NHBS VBS procedures have been previously published [11, 13] and are briefly summarized here. First, NHBS staff identified appropriate venues (eg, bars, social organizations, and sex venues) and days and times when men frequented those venues. Second, venues and corresponding days and times were chosen randomly each month for recruitment events. Third, NHBS staff systematically approached men to screen for eligibility at each recruitment event. Men eligible to be interviewed were aged ≥18 years, residents of a participating city, able to complete the interview in English or Spanish, and willing and able to provide informed consent. After participants provided informed consent, trained interviewers conducted anonymous face-to-face interviews, using a standardized behavioral questionnaire. Participants who completed the interview were given the option to complete an HIV test. HIV testing was performed by collecting blood or oral specimens for either rapid testing in the field or laboratory-based testing followed by laboratory confirmation. Participants received incentives for the interview and HIV test. The incentive format (cash or gift card) and amount varied by city, based on formative assessment and local policy. A typical incentive included $25 for the interview and $25 for HIV testing. Differences in NHBS sampling procedures across years were minor and are discussed elsewhere [9].

Ethics Statement

Activities for the NHBS were approved by local institutional review boards for each of the 20 participating cities. NHBS activities were determined to be research in which CDC was not directly engaged and, therefore, did not require review by CDC IRB [14, 15].

Measures

The 4 main outcomes in this analysis are HIV prevalence, awareness of infection, and 2 sexual risk behaviors: condomless anal sex (CAS) in the past 12 months and CAS at last sex with a partner with a discordant or unknown HIV status. During the interview, participants were asked questions regarding their sexual risk behaviors, most recent sex partner, and HIV testing history, including test results. After the interview, all participants were offered HIV testing. A nonreactive rapid test was considered a definitive negative result; a reactive (preliminary positive) rapid test result was considered a definitive positive result only when confirmed by supplemental laboratory testing (eg, Western blot, immunofluorescence assay, or nucleic acid amplification test) [16–18]. Participants with a confirmed positive HIV test result who reported having previously tested positive for HIV were considered to be aware of their infection.

Participants were asked to report their race (black/African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific islander, white, or multiple race) and ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino: yes/no) separately. A 4-category race/ethnicity variable was coded as follows: participants reporting Hispanic/Latino ethnicity were considered Hispanic, regardless of race; all non-Hispanics were categorized as black, white, or other race. Unless otherwise stated, demographic variables (age, race/ethnicity, education, and income) were analyzed as categorical variables. Sexual risk was measured on the basis of whether participants had engaged in condomless anal sex (CAS) in the previous 12 months and whether they had engaged in CAS with a partner of discordant or unknown HIV status during their most recent sexual experience. A partnership was considered to include a partner with a discordant or unknown HIV status if the participant reported that at least 1 member of the partnership (the participant or his partner) had an unknown HIV status or 1 member of the partnership was HIV positive while the other was HIV negative. Because the information was not available to participants before their most recent sexual encounter, the result of the HIV test that participants completed after the interview was not factored into this measure.

Analysis

Participants were excluded from this analysis if they did not report having had sex with another man during the previous 12 months (n = 618), did not have a definitive positive or negative NHBS HIV test result (n = 237), reported being HIV positive but had a negative NHBS HIV test result at the time of interview (n = 85), did not complete the interview (n = 53), or were determined by the interviewer to have provided responses with questionable validity (n = 19; categories are not mutually exclusive). Generalized estimating equations based on a Poisson distribution [19] were used to assess race/ethnicity and age disparities in HIV prevalence, awareness, and sexual risk among MSM interviewed in 2014. To account for the sampling method and to generate robust standard errors, recruitment venue was designated as the unit of clustering in the models. Two adjusted models are presented for each outcome (Tables 2 and 3): one for the overall results by age and race/ethnicity (without the race/ethnicity*age interaction term) and one for the results by race/ethnicity within age (with the interaction term), yielding 8 separate models. In addition to race/ethnicity and age, all models accounted for income, education, and city. Because HIV-positive MSM often alter their behavior after HIV diagnosis, self-reported HIV status was added to the risk behavior models. To highlight the disproportionate burden of HIV on black MSM as compared to MSM of other racial/ethnic groups (rather than the burden on all minority groups as compared to white MSM), the reference category is black MSM for analysis of race/ethnicity disparities. Results from 8 separate models are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Prevalence and Awareness of Infection Among Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM)—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 US Cities, 2014

| Characteristic | MSM, Total No. | HIV Prevalence |

HIV Positive, Aware of Their Infection |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSM, No. (%) | aPR (95% CI) | P Value | MSM, No. (%) | aPR (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| Age, y | Model 1 | Model 3 | |||||

| 18–24 | 1823 | 247 (14) | Reference | 160 (65) | Reference | ||

| 25–29 | 1944 | 346 (18) | 1.50 (1.30–1.73) | <.001 | 240 (69) | 1.01 (.90–1.13) | .89 |

| 30–39 | 2244 | 511 (23) | 2.05 (1.79–2.35) | <.001 | 376 (74) | 1.03 (.92–1.15) | .62 |

| 40–49 | 1501 | 447 (30) | 2.7 (2.36–3.13) | <.001 | 364 (81) | 1.1 (1.00–1.25) | .05 |

| ≥50 | 1223 | 337 (28) | 2.70 (2.32–3.13) | <.001 | 280 (83) | 1.11 (.99–1.24) | .07 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Black | 2403 | 866 (36) | Reference | 580 (67) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 2336 | 401 (17) | 0.7 (.58–.73) | <.001 | 299 (75) | 1 (.95–1.13) | .39 |

| White | 3283 | 487 (15) | 0.50 (.44–.55) | <.001 | 438 (90) | 1.15 (1.07–1.24) | <.001 |

| Othera | 669 | 126 (19) | 0.64 (.54–.75) | <.001 | 98 (78) | 1.1 (.95–1.18) | .30 |

| 18–24 y | Model 2 | Model 4 | |||||

| Black | 649 | 167 (26) | Reference | 108 (65) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 587 | 51 (9) | 0.45 (.32–.63) | <.001 | 32 (63) | 1.00 (.78–1.29) | .98 |

| White | 419 | 12 (3) | 0.2 (.09–.26) | <.001 | 8 (67) | 0.91 (.62–1.33) | .63 |

| Othera | 160 | 17 (11) | 0.48 (.31–.76) | .002 | 12 (71) | 1.04 (.75–1.44) | .81 |

| 25–29 y | |||||||

| Black | 574 | 178 (31) | Reference | 111 (62) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 547 | 81 (15) | 0.62 (.49–.79) | <.001 | 59 (73) | 1.13 (.95–1.35) | .18 |

| White | 642 | 58 (9) | 0.39 (.30–.51) | <.001 | 52 (90) | 1.29 (1.12–1.50) | <.001 |

| Othera | 168 | 26 (16) | 0.64 (.44–.93) | .02 | 17 (65) | 1.05 (.78–1.43) | .74 |

| 30–39 y | |||||||

| Black | 560 | 240 (43) | Reference | 156 (65) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 641 | 107 (17) | 0.51 (.42–.62) | <.001 | 78 (73) | 1.04 (.90–1.19) | .63 |

| White | 854 | 127 (15) | 0.45 (.37–.55) | <.001 | 113 (89) | 1.19 (1.06–1.33) | .003 |

| Othera | 174 | 33 (19) | 0.53 (.38–.73) | <.001 | 26 (79) | 1.08 (.86–1.36) | .49 |

| 40–49 y | |||||||

| Black | 377 | 170 (45) | Reference | 126 (74) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 389 | 107 (28) | 0.89 (.73–1.09) | .27 | 85 (79) | 0.98 (.86–1.12) | .80 |

| White | 641 | 146 (23) | 0.73 (.62–.86) | <.001 | 132 (90) | 1.10 (.99–1.23) | .09 |

| Othera | 91 | 24 (26) | 0.77 (.55–1.08) | .14 | 21 (88) | 1.04 (.88–1.23) | .66 |

| ≥50 y | |||||||

| Black | 243 | 111 (46) | Reference | 79 (71) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 172 | 55 (32) | 0.99 (.75–1.32) | .95 | 45 (82) | 1.06 (.90–1.25) | .48 |

| White | 727 | 144 (20) | 0.64 (.52–.79) | <.001 | 133 (92) | 1.14 (1.00–1.29) | .05 |

| Othera | 76 | 26 (34) | 0.89 (.65–1.23) | .48 | 22 (85) | 1.08 (.88–1.32) | .45 |

The table presents 4 models: (1) HIV prevalence, by age and by race; (2) HIV prevalence, by the interaction of age and race; (3) awareness of infection, by age and by race; and (4) awareness of infection, by the interaction of age and race. Age, race, income level, education level, and city were included in all models; age*race interaction terms were included in models 2 and 4.

Abbreviations: aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

a Includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or multiple race.

Table 3.

Sexual Behaviors Among Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM)—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 US Cities, 2014

| Characteristic | MSM, Total No. | CAS in Past 12 mo |

CAS With Discordant Partner at Last Sex |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSM, No. (%) | aPR (95% CI) | P Value | MSM, No. (%) | aPR (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| Age, y | Model 1 | Model 3 | |||||

| 18–24 | 1823 | 1242 (68) | Reference | 306 (17) | Reference | ||

| 25–29 | 1944 | 1386 (71) | 1.02 (.98–1.07) | .38 | 289 (15) | 0.97 (.83–1.13) | .67 |

| 30–39 | 2244 | 1544 (69) | 0.96 (.92–1.01) | .09 | 374 (17) | 1.12 (.97–1.29) | .14 |

| 40–49 | 1501 | 934 (62) | 0.9 (.81–.90) | <.001 | 275 (18) | 1.2 (1.04–1.43) | .02 |

| ≥50 | 1223 | 625 (51) | 0.69 (.65–.74) | <.001 | 175 (14) | 0.98 (.82–1.18) | .86 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Black | 2403 | 1427 (59) | Reference | 421 (18) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 2336 | 1600 (69) | 1.1 (1.09–1.20) | <.001 | 427 (18) | 1.1 (.96–1.29) | .17 |

| White | 3283 | 2231 (68) | 1.17 (1.11–1.22) | <.001 | 471 (14) | 1.00 (.87–1.17) | .95 |

| Othera | 669 | 446 (67) | 1.10 (1.02–1.18) | .01 | 94 (14) | .95 (.76–1.17) | .61 |

| 18–24 y | Model 2 | Model 4 | |||||

| Black | 649 | 402 (62) | Reference | 111 (17) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 587 | 409 (70) | 1.11 (1.02–1.20) | .01 | 116 (20) | 1.18 (.94–1.48) | .16 |

| White | 419 | 306 (74) | 1.2 (1.05–1.27) | .002 | 61 (15) | 0.98 (.73–1.32) | .89 |

| Othera | 160 | 120 (75) | 1.16 (1.04–1.30) | .006 | 16 (10) | 0.67 (.39–1.13) | .13 |

| 25–29 y | |||||||

| Black | 574 | 384 (67) | Reference | 90 (16) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 547 | 402 (74) | 1.10 (1.02–1.20) | .02 | 91 (17) | 1.10 (.84–1.43) | .49 |

| White | 642 | 473 (74) | 1.08 (1.00–1.17) | .06 | 79 (12) | 0.95 (.72–1.27) | .74 |

| Othera | 168 | 119 (71) | 1.05 (.94–1.18) | .38 | 27 (16) | 1.20 (.80–1.80) | .37 |

| 30–39 y | |||||||

| Black | 560 | 316 (56) | Reference | 90 (16) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 641 | 461 (72) | 1.28 (1.17–1.40) | <.001 | 119 (19) | 1.24 (.97–1.60) | .09 |

| White | 854 | 637 (75) | 1.29 (1.19–1.40) | <.001 | 136 (16) | 1.19 (.93–1.52) | .17 |

| Othera | 174 | 122 (71) | 1.22 (1.06–1.39) | .004 | 27 (16) | 1.09 (.70–1.72) | .69 |

| 40–49 y | |||||||

| Black | 377 | 212 (56) | Reference | 88 (23) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 389 | 238 (61) | 1.09 (.96–1.24) | .20 | 70 (18) | 0.88 (.64–1.20) | .41 |

| White | 641 | 435 (68) | 1.18 (1.05–1.31) | .004 | 106 (17) | 0.90 (.69–1.18) | .44 |

| Othera | 91 | 47 (52) | 0.90 (.72–1.12) | .35 | 11 (12) | 0.65 (.37–1.16) | .14 |

| ≥50 y | |||||||

| Black | 243 | 113 (47) | Reference | 42 (17) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 172 | 90 (52) | 1.10 (.91–1.32) | .32 | 31 (18) | 1.19 (.77–1.83) | .43 |

| White | 727 | 380 (52) | 1.08 (.94–1.25) | .27 | 89 (12) | 0.98 (.68–1.40) | .90 |

| Othera | 76 | 38 (50) | 1.02 (.77–1.35) | .91 | 13 (18) | 1.26 (.71–2.27) | .43 |

The table presents 4 models: (1) CAS, by age and by race; (2) CAS, by the interaction of age and race; (3) CAS with discordant partner at last sex, by age and by race; and (4) CAS with discordant partner at last sex, by the interaction of age and race. Age, race, income level, education level, city, and self-reported HIV status were included in all models; age*race interaction terms were included in models 2 and 4.

Abbreviations: aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio; CAS, condomless anal sex; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

a Includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or multiple race.

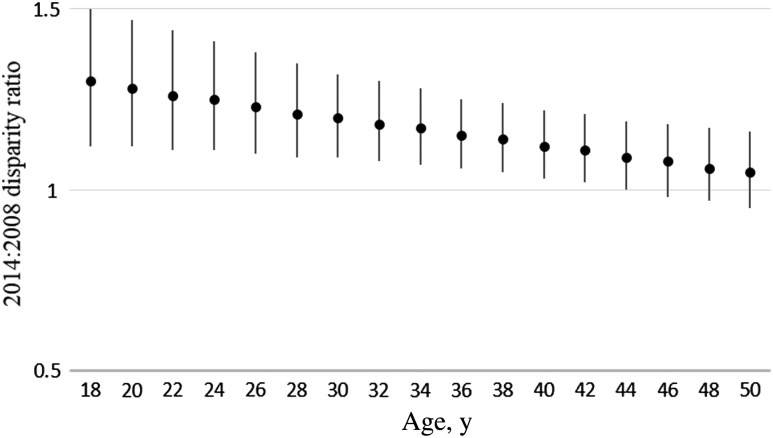

Further analysis using generalized estimating equations based on a Poisson distribution with robust standard error was conducted to determine whether the degree of racial disparity in HIV prevalence and awareness had changed between 2008 and 2014. These models used combined data from NHBS collected in 2008, 2011, and 2014 and included an interaction between race/ethnicity and continuous year. A model with continuous age and a 3-way interaction (race/ethnicity*age*year) was used to examine changes in race/ethnicity disparities in HIV prevalence between black and white MSM by age (Figure 3). The focus of this article is race/ethnicity disparities by age observed in 2014 and changes in the disparities in HIV prevalence and awareness from 2008 to 2014. NHBS-2008 and NHBS-2011 methods and outcomes are reported elsewhere [9, 11, 20].

Figure 3.

Change in disparity in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence from 2008 to 2014 between black and white men who have sex with men (MSM), by age, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 US cities. Estimates and 95% confidence intervals were based on a 3-way interaction (age*race/ethnicity*year) term in which age and year were treated as a continuous variable. Estimates of >1 signify that the disparity increased during 2008–2014. Age, race/ethnicity, income level, education level, and city were included in the model.

For all models, prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented. Analyses were completed using PROC GENMOD in SAS, version 9.3. Sampling weights were not available [9].

RESULTS

Disparities in 2014

A total of 8735 MSM interviewed and tested in 2014 were included in this analysis. Characteristics of the 2014 sample are presented in Table 1. MSM aged 18–24, 25–29, and 30–39 years each made up approximately 20%–25% of the sample; MSM aged 40–49 and ≥50 years of age each made up approximately 15% of the sample. Whites made up 38% of the sample, while approximately one fourth of the sample was black and one fourth was Hispanic.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 8735 Men Who Have Sex With Men—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 US Cities, 2014

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| 18–24 | 1823 (21) |

| 25–29 | 1944 (22) |

| 30–39 | 2244 (26) |

| 40–49 | 1501 (17) |

| ≥50 | 1223 (14) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latinoa | 2336 (27) |

| Black | 2403 (28) |

| White | 3283 (38) |

| Otherb | 669 (8) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school graduate | 386 (4) |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 1945 (22) |

| Some college or technical college | 2862 (33) |

| College degree or higher education | 3541 (41) |

| Annual household income, $ | |

| 0–19 999 | 2742 (32) |

| 20 000–39 999 | 2117 (25) |

| 40 000–74 999 | 2085 (24) |

| ≥75 000 | 1679 (20) |

Abbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

a Persons of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity might be of any race.

b Includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or multiple race.

Table 2 shows HIV prevalence and awareness of infection among MSM interviewed in 2014. Overall, HIV prevalence increased with age, was highest among black MSM, and was lowest among white MSM. In adjusted analysis, young MSM aged 18–24 years had a significantly lower prevalence of HIV infection than other age groups. HIV prevalence among all racial groups was significantly lower than among black MSM (P ≤ .001, for all races/ethnicities). A separate model was used to analyze age-specific racial disparities in HIV prevalence after adjustment for education, income, and city. Over 25% of black MSM aged 18–24 years were infected with HIV, while 3% of white MSM aged 18–24 years were infected with HIV. While the gap in HIV prevalence between black MSM and MSM of other racial/ethnic groups decreased with age, the adjusted prevalence ratio for the comparison of HIV prevalence among black MSM to that among Hispanic, white, and other races of MSM remained significant in all age categories <40 years. Significant disparities in HIV prevalence between black and white MSM persisted in all age categories. Awareness of HIV infection among HIV-positive MSM in 2014 increased with age and was significantly higher among white MSM (90%) than among black MSM (67%; P < .001). However, few significant differences in awareness of infection were observed by race within age categories.

Black MSM, overall and for ages 18–24, 30–39, and 40–49 years, were significantly less likely than their white counterparts to report having had any CAS in the past 12 months (Table 3). Further, we did not find significant differences by race/ethnicity in the percentage of men who reported having CAS with a partner who had a discordant or unknown HIV status at last sex (Table 3).

Changes in Disparities From 2008 to 2014

Characteristics and response rates for the 2008 and 2011 samples have been presented elsewhere [9]. Analysis of the change in disparities from 2008 to 2014 (data not shown) found that the disparity in HIV prevalence increased significantly from 2008 to 2014 between black MSM and white MSM (P = .002) but not between black and Hispanic MSM (P = .23) or between black MSM and MSM of other racial/ethnic groups (P = .51). Figure 1 shows HIV prevalence, by race, for MSM interviewed in 2008, 2011, and 2014. The increase in disparity between black MSM and white MSM is in part due to an increase in HIV prevalence among black MSM (P < .001). The increase in disparities in HIV prevalence between black and white MSM was greatest among young MSM. Figure 2 illustrates the change in HIV prevalence, by race, among MSM aged 18–24 years. From 2008 to 2014, HIV prevalence among MSM aged 18–24 years increased from 17% to 26% among black MSM (P < .001) but decreased from 6% to 3% among white MSM (P = .03). As a result, the disparity in HIV prevalence between black and white MSM aged 18–24 years increased from 2008 to 2014 (P < .001). Figure 3 presents data for black and white MSM only and shows the change in disparity between black and white MSM at different ages, based on a model of continuous age. Values of >1 represent differences in the slope of HIV prevalence from 2008 to 2014 between black and white MSM that indicate an increase in the disparity at a particular age. The increase in disparity was greatest for young MSM and decreased with age: the disparity in HIV prevalence between black and white MSM increased significantly among MSM aged ≤44 years (P < .05). While the disparity did not increase significantly among men aged >44 years, it did not decrease from 2008 to 2014 among MSM of any age.

Figure 1.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence among men who have sex with men (MSM) who were interviewed in 2008, 2011, and 2014, by year of interview, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 US cities. Disparities between black and white MSM increased from 2008 to 2014 (P = .002). Age, race/ethnicity, income, education, and city were included in the model.

Figure 2.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence among 18–24-year-old men who have sex with men (MSM) who were interviewed in 2008, 2011, and 2014, by year of interview, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 US cities. The HIV prevalence among black MSM aged 18–24 years steadily increased during 2008–2014. The disparity in HIV prevalence between black and white MSM aged 18–24 years increased, as well (P < .001). Age, race/ethnicity, income level, education level, and city were included in the model.

Awareness of HIV infection increased for all racial/ethnic groups (Figure 4; P < .001 for each race). Disparity in awareness between white and black MSM decreased from 2008 to 2014 (P = .002).

Figure 4.

Awareness of infection among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive men who have sex with men (MSM) of all ages who were interviewed in 2008, 2011, and 2014, by year of interview, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 US cities. Awareness of infection increased during 2008–2014 in all racial/ethnic groups (P < .001 for each category). Age, race/ethnicity, income level, education level, and city were included in the model.

DISCUSSION

This analysis documented racial disparities in HIV prevalence and awareness of HIV infection among MSM in 20 US cities in 2014 and found that black MSM have the highest HIV prevalence and lowest awareness of their HIV infection. Additionally, our results suggest that the disparity in HIV prevalence between black and white MSM, especially among young MSM, may be increasing. While HIV prevalence among young white MSM decreased from 2008 to 2014, the prevalence among young black MSM increased. Consistent with previous work [9] our results showed the disparity in awareness between black and white MSM has diminished, but this is likely due to a ceiling effect limiting the increase in awareness among white MSM from 2011 to 2014.

Consistent with other data showing that HIV prevalence and incidence among young black MSM is high [1, 5, 21], we observed a disparity in HIV prevalence between black and white MSM for all age groups. For black MSM, the risk of HIV infection begins at a young age. Over 25% of black MSM aged 18–24 years interviewed in 2014 were infected with HIV. HIV prevalence typically increases with age. In this analysis, the 25% prevalence mark observed for young black MSM was not reached among Hispanic MSM until the 40–49-year age group and was never reached among white MSM.

A number of factors may be contributing to the increased HIV prevalence among black MSM in general and young black MSM in particular. As documented previously [2, 22], our analysis also suggested that individual behavioral risk factors for HIV infection do not explain elevated HIV rates among black MSM or young black MSM. However, black MSM are more likely to report black partners and to have higher HIV prevalence and transmission potential in their sex partner pool [4, 5] and may have a higher prevalence of HIV in their social networks than other MSM [23]. Black MSM have higher reports of structural barriers that may increase HIV infection risk, such as unemployment, low income, previous incarceration, less education, and reduced access to care [2]. HIV-positive black MSM, especially young black MSM, are less likely to be aware of their HIV status, likely because of recent infection, underestimation of infection risk, and fewer testing opportunities [9, 24]. Persons not aware of their infection are unable to seek treatment and are unaware of the risk of transmitting HIV to others. Additionally, black MSM are less likely to achieve each step along the HIV continuum of care, including viral suppression [2, 6, 25]. HIV treatment and viral suppression have been shown to be effective at preventing HIV transmission [26, 27]. Social factors, including HIV stigma, discrimination, and homophobia, affect whether MSM seek and obtain health services and may disproportionately affect young black MSM [28, 29].

Despite these challenges, some progress has been made. Earlier analyses of NHBS data from 2008 and 2011 found significant increases in recent HIV testing among black MSM in general and among young black MSM in particular [3]; the percentage of all MSM aware of their HIV status, including black MSM [9]; and the percentage of all HIV-positive MSM, including black MSM, currently taking ART [30]. Reducing disparities in HIV infection among black MSM and young black MSM in particular continues to be an important goal of the updated NHAS [8] but will likely require high coverage of effective interventions, such as preexposure prophylaxis and behavioral interventions, to increase outcomes along the continuum of care and to prevent new infections [25].

HIV prevalence among young black MSM is not only high but has steadily increased in recent years. Approximately 1 in 4 black MSM aged 18–24 years were infected with HIV in 2014, compared with 1 in 5 in 2011 and 1 in 6 in 2008. This is in contrast to the HIV prevalence among young white MSM, which has decreased from 1 in 16 in 2008 to 1 in 34 in 2014. As a result, the disparity in HIV prevalence between white and black MSM, especially young MSM, has increased.

The increased disparity between whites and blacks among young MSM is partially driven by the decrease in HIV prevalence among young white MSM. The reasons for this decrease are unclear and complex, but differences in awareness of infection likely play an important role. In this analysis, awareness among white MSM was 90% overall and significantly higher than for black MSM overall. While awareness of infection was not higher among young white MSM than young black MSM, HIV prevalence among young white MSM was 6 times lower (3%) than among young black MSM (26%). Due to high racial concordance in sex partners [4], young white MSM are less likely to encounter a partner who is HIV positive in general and unaware of his infection in particular than young black MSM, even if age-mixing occurs within race. Further, the likelihood among young white MSM of encountering an HIV-positive MSM who is unaware of his status may be low enough to result in a reduction of HIV prevalence; that is, the rate of HIV transmission to young white MSM may be below replacement. Despite contributing to increased racial disparities, decreased HIV prevalence among young white MSM highlights the potential of sustained prevention efforts to reduce HIV infection and the need for additional, sustained efforts focused on young black MSM.

An important limitation of this analysis is its reliance on prevalence rather than incidence of HIV. Measures of prevalence can be affected by changes in testing or survival. By using HIV test result results, rather than self-reported HIV status, to determine HIV prevalence, this analysis mitigates the impact of increased HIV testing efforts among MSM. However, our analysis does not account for date of HIV acquisition, which was not known, and consequently may not necessarily reflect current trends in HIV acquisition among all MSM. Nonetheless, the results presented here among young MSM likely do reflect current trends in HIV acquisition because young MSM have had less time to become infected. Similarly, analysis of changes in prevalence among older MSM may be diluted by the presence of MSM who have been infected for longer than the analysis period or who became infected at younger ages.

In addition to its reliance on prevalence, this analysis is subject to several limitations. First, MSM were recruited in US cities with a high AIDS burden, and results may not be generalizable to all cities or all MSM. Second, our measures of awareness and risk behavior are based on self-reported data and may be subject to social desirability bias. Such bias would be especially problematic if it differed by race or ethnicity, for which some evidence exists [31]. Third, data are not weighted to account for the complex sampling methods required to locate, recruit, and interview MSM. Variables typically correlated with VBS sampling weights (ie, race/ethnicity, age, venue, and city) were included in the analysis models to adjust for sampling differences and clustering. Finally, the survey population is limited to MSM who attend venues; MSM who do not attend venues may, or may not, differ from the survey population on key outcomes.

This analysis documented racial disparities in HIV prevalence and awareness of HIV infection among MSM. These disparities are especially striking among young MSM. Among black MSM aged 18–24 years, 1 in 4 was infected with HIV. Further, racial disparity in HIV prevalence increased from 2008 to 2014, especially among young MSM. Research suggests that the task of eliminating racial disparities among MSM is daunting [25]. While some progress toward reducing the burden of HIV among black MSM has been made, HIV prevalence among young black MSM continues to increase. Black MSM are being infected with HIV at young ages, requiring a targeted response, especially for young black MSM.

STUDY GROUP MEMBERS

Members of the NHBS study group are as follows: Atlanta, GA: Pascale Wortley, Jennifer Taussig, Robert Gern, Tamika Hoyte, Laura Salazar, Jianglan White, Jeff Todd, Greg Bautista, and Kimi Sato; Baltimore, MD: Colin Flynn, Frangiscos Sifakis, and Danielle German; Boston, MA: Dawn Fukuda, Debbie Isenberg, Maura Driscoll, Elizabeth Hurwitz, Maura Miminos, Rose Doherty, and Chris Wittke; Chicago, IL: Antonio D. Jimenez, Nikhil Prachand, and Nanette Benbow; Dallas, TX: Jonathon Poe, Sharon Melville, Praveen Pannala, Richard Yeager, Aaron Sayegh, Jim Dyer, Shane Sheu, and Alicia Novoa; Denver, CO: Melanie Mattson, Mark Thrun, Alia Al-Tayyib, and Ralph Wilmoth; Detroit, MI: Kathryn Macomber, Emily Higgins, Vivian Griffin, Eve Mokotoff, and Karen MacMaster; Houston, TX: Salma Khuwaja, Marcia Wolverton, Jan Risser, Hafeez Rehman, and Paige Padgett; Los Angeles, CA: Yingbo Ma, Trista Bingham, and Ekow Kwa Sey; Miami, FL: John-Mark Schacht, Marlene LaLota, Lisa Metsch, David Forrest, Dano Beck, and Gabriel Cardenas; Nassau-Suffolk, NY: Amber Sinclair, Chris Nemeth, Bridget J. Anderson, Carol-Ann Watson, and Lou Smith; New Orleans, LA: William T. Robinson, Meagan C. Zarwell, DeAnn Gruber, and Narquis Barak; New York City, NY: Chris Murrill, Alan Neaigus, Samuel Jenness, Holly Hagan, Kathleen H. Reilly, and Travis Wendel; Newark, NJ: Helene Cross, Barbara Bolden, Sally D'Errico, Afework Wogayehu, and Henry Godette; Philadelphia, PA: Kathleen A. Brady, Mark Shpaner, Jennifer Shinefeld, Althea Kirkland, and Andrea Sifferman; San Diego, CA: Vanessa Miguelino-Keasling, Lissa Bayang, Al Velasco, and Veronica Tovar; San Francisco, CA: H. Fisher Raymond and Theresa Ick; San Juan, PR: Sandra Miranda De León, Yadira Rolón-Colón, and Melissa Marzan; Seattle, WA: Maria Courogen, Tom Jaenicke, Hanne Thiede, and Richard Burt; Washington, DC: Yujiang Jia, Jenevieve Opoku, Marie Sansone, Tiffany West, Manya Magnus, and Irene Kuo; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta: Behavioral Surveillance Team.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank all of the NHBS 2008, 2011, and 2014 participants.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Financial support. This work was supported by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the CDC, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the US Department of Energy and CDC.

Potential conflict of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV surveillance supplemental report. Vol 17. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2012; 380:341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cooley LA, Oster AM, Rose CE et al. Increases in HIV testing among men who have sex with men - National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 20 U.S. metropolitan statistical areas, 2008 and 2011. Plos One 2014; 9:e104162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kelley CF, Rosenberg ES, O'Hara BM et al. Measuring population transmission risk for HIV: an alternative metric of exposure risk in men who have sex with men (MSM) in the US. Plos One 2012; 7:e53284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sullivan PS, Rosenberg ES, Sanchez TH et al. Explaining racial disparities in HIV incidence in black and white men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA: a prospective observational cohort study. Ann Epidemiol 2015; 25:445–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beer L, Oster AM, Mattson CL, Skarbinski J, Medical Monitoring P. Disparities in HIV transmission risk among HIV-infected black and white men who have sex with men, United States, 2009. AIDS 2014; 28:105–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf. Published July 2010. Accessed 4 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States: Updated to 2020. https://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/overview/. Published July 2015. Accessed 4 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wejnert C, Le B, Rose CE et al. HIV infection and awareness among men who have sex with men-20 cities, United States, 2008 and 2011. Plos One 2013; 8:e76878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gallagher KM, Sullivan PS, Lansky A, Onorato IM. Behavioral surveillance among people at risk for HIV infection in the U.S.: the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System. Public Health Rep 2007; 122(suppl 1):32–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Finlayson TJ, Le B, Smith A et al. HIV risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among men who have sex with men--National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 21 U.S. cities, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011; 60:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV risk, prevention, and testing behaviors. National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System: men who have sex with men, 20 US cities, 2011. In: HIV surveillance special report 8. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. MacKellar DA, Gallagher KM, Finlayson T, Sanchez T, Lansky A, Sullivan PS. Surveillance of HIV risk and prevention behaviors of men who have sex with men--a national application of venue-based, time-space sampling. Public Health Rep 2007; 122(suppl 1):39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for defining public health research and public health non-research. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Protection of human subjects. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html. Accessed 4 November 2014.

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Notice to readers: protocols for confirmation of reactive rapid HIV tests. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004; 53:221–2. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: HIV counseling and testing using rapid tests--United States, 1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1998; 47:211–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interpretation and use of the western blot assay for serodiagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1989; 38:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003; 3:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence and awareness of HIV infection among men who have sex with men—21 cities, United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010; 59:1201–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sullivan PS, Peterson J, Rosenberg ES et al. Understanding racial HIV/STI disparities in black and white men who have sex with men: a multilevel approach. PLoS One 2014; 9:e90514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS 2007; 21:2083–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hernandez-Romieu AC, Sullivan PS, Rothenberg R et al. Heterogeneity of HIV prevalence among the sexual networks of black and white men who have sex with men in Atlanta: illuminating a mechanism for increased HIV risk for young black men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2015; 42:505–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crepaz N, Hart TA, Marks G. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review. JAMA 2004; 292:224–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rosenberg ES, Millett GA, Sullivan PS, Del Rio C, Curran JW. Understanding the HIV disparities between black and white men who have sex with men in the USA using the HIV care continuum: a modeling study. Lancet HIV 2014; 1:e112–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cohen J. Breakthrough of the year. HIV treatment as prevention. Science 2011; 334:1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cohen MS, McCauley M, Gamble TR. HIV treatment as prevention and HPTN 052. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2012; 7:99–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wolitski RJ, Fenton KA. Sexual health, HIV, and sexually transmitted infections among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS Behav 2011; 15(suppl 1):S9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Balaji AB, Oster AM, Viall AH, Heffelfinger JD, Mena LA, Toledo CA. Role flexing: how community, religion, and family shape the experiences of young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012; 26:730–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hoots BH, Finlayson TJ, Wejnert C, Paz-Bailey G, for the NHBS Study Group. Early linkage to HIV care and antiretroviral treatment among men who have sex with men—20 cities, United States, 2008 and 2011. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0132962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. White D, Rosenberg ES, Cooper HL et al. Racial differences in the validity of self-reported drug use among men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014; 138:146–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]