Abstract

Esophageal perforation (Boerhaave's syndrome) is a severe life-threatening disorder. Diagnosis and treatment are often delayed due to the wide variety of presenting symptoms. This case report details an unusual presentation of Boerhaave's syndrome in a 48-year-old man mimicking an acute anterior myocardial infarction. We present the history, clinical, angiographic, and computed tomographic (CT) findings, as well as the subsequent management and clinical outcome. We demonstrate the rare angiographic finding of right heart hypermobility, which was strongly suggestive of a non-cardiac diagnosis in a patient with ST segment elevation and cardiovascular compromise

<Learning objective: Treatment of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction mandates rapid treatment with primary angioplasty to reduce ischemic time and minimize myocardial damage. Patients are transferred directly to catheterization laboratories, and undergo rapid clinical assessment. Such patients may be unstable, or present with atypical history or examination findings. In order to prevent significant delay, ancillary investigations, such as chest radiography are not usually undertaken until after reperfusion of the coronary artery. In this case, with atypical findings, we show important fluoroscopic findings which are rarely seen, and are strongly suggestive of an alternative diagnosis. Clinicians should be wary of the hypermobile right heart.>

Keywords: Diagnosis, Shock, Myocardial infarction, Fluoroscopy, Angiography

Introduction

Patients presenting with ST elevation myocardial infarction require prompt treatment by percutaneous coronary intervention. This case report highlights the importance of consideration of alternative diagnosis in patients with atypical clinical findings and describes the important clinical sign of angiographic right heart hypermobility which operators may encounter in the catheter laboratory, which alerted operators to significant non-cardiac pathology.

Case report

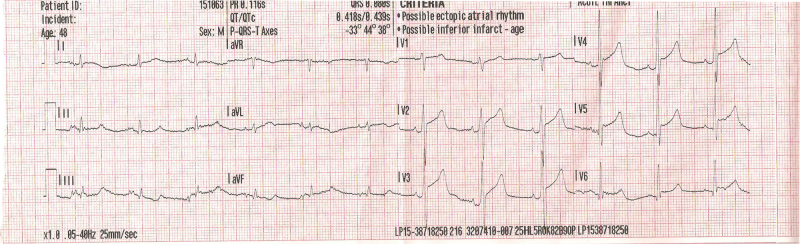

A 48-year-old man presented via ambulance directly to a tertiary cardiac center with anterior ST elevation on electrocardiogram (ECG) performed by the regional ambulance service (Fig. 1). His history was vague, but included 2 days of shortness of breath, as well as presyncope, retrosternal, dull chest pain of 3-h duration and an episode of collapse which led to his presentation. His background history was of type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, bipolar disorder, alcohol excess, and cigarette smoking. He had never been hospitalized. He appeared sweating profusely and was shocked, with cool peripheries, blood pressure of 82/66 mmHg, heart rate of 72 beats/min (despite long-term beta blocker therapy), and respiratory rate of 35. Oxygen saturations measured 90% despite 15 l/min of oxygen being delivered by face mask. Ecchymoses of his right arm was noted. Auscultation did not reveal any cardiac murmur. There was marked polyphonic wheeze present throughout both lung fields and reduced air entry in the right hemi-thorax, with associated dullness to percussion at the right base. There was no tracheal deviation.

Fig. 1.

Electrocardiograph demonstrating anterior ST elevation on presentation to emergency medical services.

The chest findings were of concern to us, indicating the possibility of significant pulmonary or other co-existent pathology. However, given the ECG findings, we felt that it was critical to rule out an acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) as the acute event causing cardiovascular compromise.

The critical care team was contacted on the patient's arrival in anticipation of the requirement for ventilatory and inotropic support. The patient gave consent and was taken to the catheterization laboratory. Arterial sheaths were placed bi-femorally in anticipation of intra-aortic balloon pump insertion. A noradrenaline infusion was commenced.

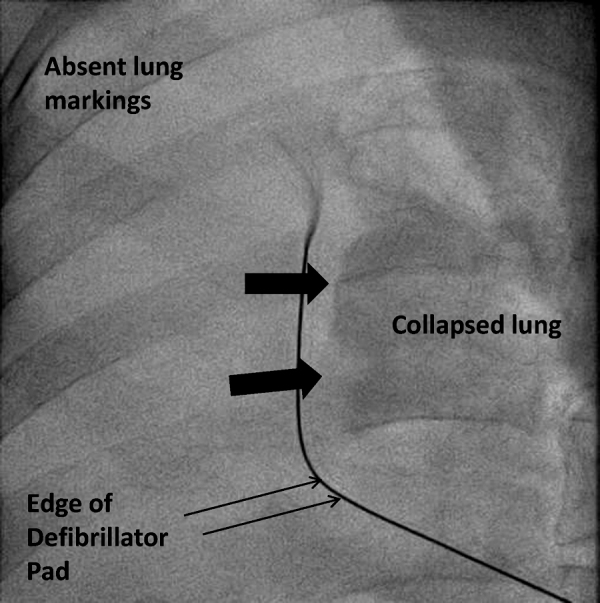

A six-French Judkins right coronary catheter was passed into the ascending aorta, and on screening of the J-tipped wire over the aortic arch, the right heart motion was noted to be grossly abnormal (Video 1). This hyperdynamic appearance, along with our examination findings increased our suspicion of a very significant pulmonary pathology. Fluoroscopy of the right hemi-thorax was carried out (Fig. 2), which demonstrated a large right-sided pneumothorax. The cardiothoracic surgical team was contacted for assistance at this point. We suspected that there might have been a traumatic right sided pneumothorax, given the history of alcohol excess, collapse, and bruising on the right arm.

Fig. 2.

Still fluoroscopic image demonstrating right sided pneumothorax, with lung edge shown by large arrows, and absent lung markings at the periphery.

We completed our angiographic study, which revealed only mild to moderate disease of the left anterior descending artery, and a small, non-dominant, but normal right coronary artery.

Subsequent measurement of troponins was carried out and found to be negative.

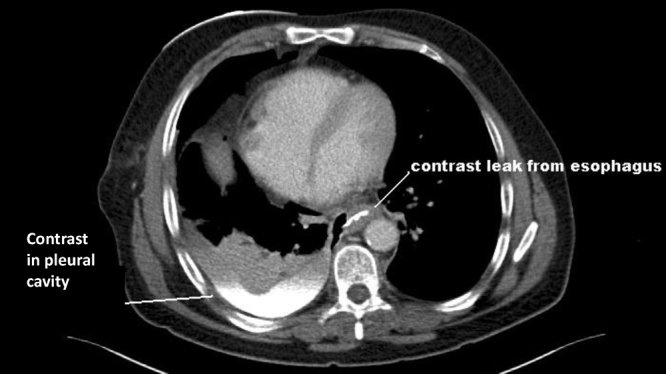

The cardiothoracic team placed a large-bore chest drain which drained copious amounts of bilious fluid. The patient was intubated and ventilated. CT scan was requested (Fig. 3), which confirmed the presence of a perforated esophagus. The patient was referred to the upper gastro-intestinal surgeons and underwent emergency upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy, which confirmed a 1 cm esophageal perforation at 35 cm, which was leaking into the right pleural space. He underwent laparotomy and repair, his post-operative course was unremarkable except for a brief episode of respiratory sepsis, managed by intensive antibiotic therapy, and non-invasive ventilation. He thereafter recovered, and has since been discharged home, where he remains well to date. Pre-discharge echocardiography demonstrated normal resting left and right ventricular function.

Fig. 3.

Computed tomography scan showing contrast leak from esophagus to right pleural space (denoted by lines).

Discussion

The treatment of choice for acute STEMI is primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI). To prevent delay in treatment, patients presenting with STEMI are often delivered directly to centers with the ability to perform PPCI. Often these patients are unstable and critically unwell, and the priority is to perform PPCI, without adding delay by conducting other investigations such as chest X-ray or CT scans. This case illustrates the importance of considering alternative diagnoses for the ECG findings when atypical examination findings are identified. In this case, the possibility of an alternative diagnosis was considered from the outset, which prevented significant delay in the patient receiving treatment for esophageal perforation, which itself is a life-threatening condition.

Boerhaave's syndrome is the eponymous name given to esophageal perforation, named after its first descriptor. The first case was described in 1724, a patient who died 18 h after self-induced vomiting, with undigested food being found in the left pleural space [1]. This condition often presents in a non-specific manner, and if not recognized and treated promptly, may result in rapid deterioration and death. Mackler's triad describes the typical history of esophageal perforation, where vomiting precedes chest pain and development of subcutaneous emphysema [2]. However, the majority of cases do not present in such a typical manner – instead showing non-specific signs such as profound hypotension, chest pain, or respiratory problems [3]. A previous review of the literature suggests in fact that clinical examination and history taking lead to the diagnosis in only 26% of cases [4]. There are previous reports in the literature of Boerhaave's causing anterior ST elevation, due to mediastinitis, which mimics myocardial infarction [5], [6].

In this case, the possibility of significant non-cardiac pathology was suspected from the outset, which prevented delay in diagnosis and treatment of esophageal perforation. The decision to take the patient to the catheter laboratory was based on the history of chest pain, high risk factor profile, ECG findings, and severe shock. Initial fluoroscopic findings indicated that there was grossly abnormal right heart motion. This is rarely seen, and is an important sign for operators to recognize in patients who are critically unwell, to direct further investigation. This was the result of raised intra-thoracic pressure causing mediastinal shift, impairing venous return to the right atrium, and is not specific for the diagnosis of esophageal perforation. Given that life-threatening non-cardiac disease (such as esophageal perforation) may present as myocardial infarction, we feel that this is an important warning sign which cardiologists should be aware of, found at the time of emergency angiography which strongly suggests the presence of a life-threatening, non-cardiac pathology.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jccase.2013.03.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Boerhaave H. Atrocis nec descripti prius, morbi historia, Secundum mediciae artis leges conscripta. Lugd Bat Boutesteniana Leyeden, 1724. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1955;43:217. [English translation] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackler S.A. Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1952;95:344–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Backer C.L., LoCicero J., Hartz R.S., Donaldson J.S., Shields T. Computed tomography in patients with esophageal perforation. Chest. 1990;98:1078–1080. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.5.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pate J.W., Walker W.A., Cole F.H., Jr., Owen E.W., Johnson W.H. Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus: a 30 year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;47:689–692. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mansour K.A., Teaford H. Atraumatic rupture of the esophagus into the pericardium simulating acute myocardial infarction. A case report. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1973;65:458–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosseri M., Eliakim R., Mogle P. Perforation of the oesophagus electrocardiographically mimicking myocardial infarction. Isr J Med Sci. 1986;22:451–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.