Abstract

We herein report a rare autopsy case of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) presenting ventricular tachycardia after pacemaker implantation. A 69-year-old male received a dual-chamber pacemaker implantation for complete atrioventricular block. He had no chest symptoms after the operation. Three days later, he developed severe chest pain, followed by syncope. Electrocardiogram showed sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Despite the use of amiodarone and frequent electrical defibrillation, ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation were repeated incessantly. He died 24 h after the syncope. The autopsy revealed no hemopericardial effusion, or perforation of leads. There were also no obstructive lesions in the coronary arteries. Myocardial necrosis was observed in the entire circumference and the all layers of the left ventricle. Microscopically, myocardial necrosis was plurifocal and contraction band necrosis. We speculate that catecholamine cardiotoxicity caused ventricular tachycardia in this case. Further studies are needed to clarify the heterogeneity of this disease.

<Learning objective: Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy should be considered a potential complication of pacemaker implantation. Physicians should recognize that this disorder can occur unexpectedly during medical examination or treatment.>

Keywords: Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy, Pacemaker implantation, Ventricular tachycardia, Contraction band necrosis

Introduction

Stress-induced (tako-tsubo) cardiomyopathy (TTC) is characterized by transient hypokinesis of the left ventricular mid segments with or without apical involvement; the regional wall motion abnormalities extend beyond a single epicardial vascular distribution; a stressful trigger is often, but not always present, absence of obstructive coronary artery disease, new electrocardiographic abnormalities (either ST-segment elevation and/or T wave inversion), or modest elevation in cardiac troponin and absence of pheocromocytoma and myocarditis [1]. Several possible mechanisms have been proposed to explain TTC, but its pathophysiology is not well understood [1]. We herein report a rare autopsy case of TTC presenting ventricular tachycardia after pacemaker implantation.

Case report

A 69-year-old Japanese male with hypertension was admitted to our hospital with dizziness. His medications included nifedipine CR and olmesartan. He was conscious, his blood pressure was 146/82 mmHg, and pulse rate was 38 beats per minute (bpm). Routine hematological tests were normal, and chest X-ray showed no pulmonary edema or cardiac enlargement.

A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm and complete atrioventricular block (CAVB), at a rate of 40 bpm (Fig. 1A), and echocardiography showed normal left ventricular function with an ejection fraction (EF) of 72%. The next day, he received a dual-chamber pacemaker under local anesthesia. The pulse generator was located in the left pectoral region, and the 52-cm and 58-cm bipolar leads were positioned in the high right atrial septum and mid right ventricular septum respectively (Reply DR, Sorin, Milan, Italy). The programed mode of the pacemaker was DDD, and the programed rate was 70 bpm. No complications occurred during the operation.

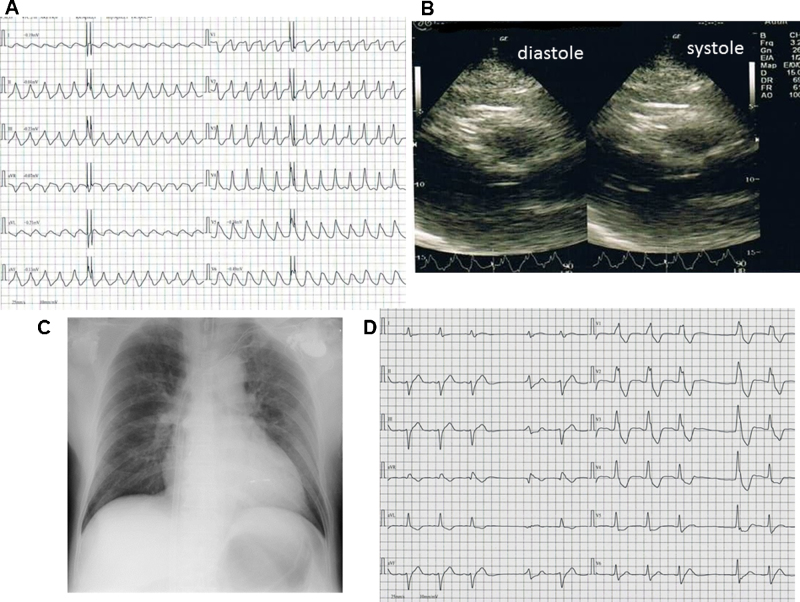

Fig. 1.

(A) Twelve-lead electrocardiogram at hospital admission; (B) twelve-lead electrocardiogram after pacemaker implantation; and (C) chest X-ray after pacemaker implantation.

He had no chest symptoms after the operation. Post-implantation ECG showed a paced rhythm at 70 bpm (Fig. 1B). Post-implantation chest X-ray showed no evidence of pneumothorax and no dislocation of endocardial leads (Fig. 1C). He was carefully monitored by telemetry from admission and had no episodes of dysrhythmia after the operation. His systolic blood pressure remained stable between about 120 and 130 mmHg. Three days later, he developed severe chest pain, followed by syncope. ECG showed sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia with a left bundle branch block and right axis (Fig. 2A). An urgent echocardiograph showed depressed global systolic function with an EF of 38% and dyskinesia involving apical segments (Fig. 2B). Blood markers of cardiac ischemia and electrolytes were in the normal range. Chest X-ray showed pulmonary edema and cardiac enlargement, but no dislocation of endocardial leads (Fig. 2C). The pacing thresholds, sensing thresholds, and lead impedance in the atrial and ventricular leads were unremarkable. We performed cardioversion for ventricular tachycardia. The ECG after cardioversion showed idioventricular rhythm, left axis and right bundle branch block (Fig. 2D). Immediate cardiopulmonary support was initiated, and vasopressors such as dopamine, dobutamine, and epinephrine and antiarrhythmic agent such as amiodarone were used. When ventricular tachycardia started, there was a warm-up phenomenon. Despite the use of amiodarone and frequent electrical defibrillation, ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation were repeated incessantly. The patient remained unconscious and died 24 h after the syncope.

Fig. 2.

(A) Sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia with left bundle branch block and right axis with a frequency of 160 beats per minute; (B) an urgent echocardiography at the bedside (parasternal long axis view); (C) chest X-ray at the time of sudden change and (D) twelve-lead electrocardiogram after cardioversion.

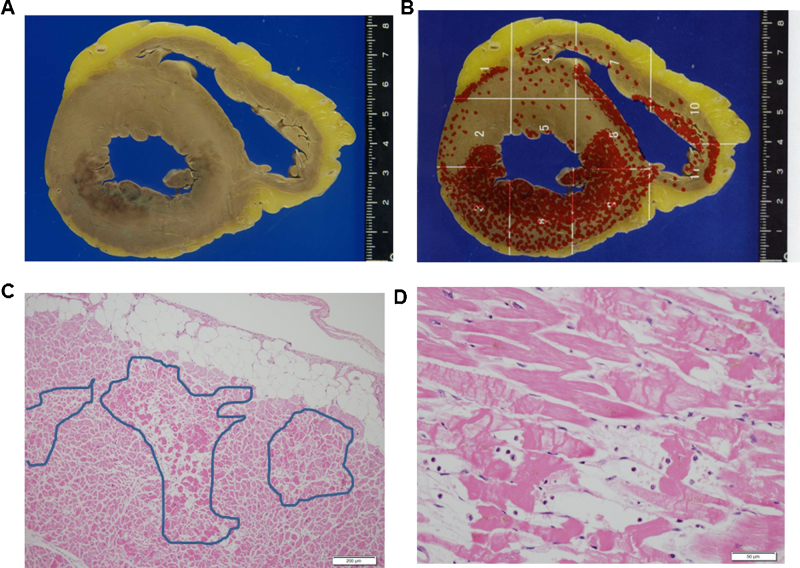

An autopsy was performed at 6 h after death. The autopsy revealed no hemopericardial effusion, or perforation of leads. There were also no obstructive lesions in the coronary arteries. Myocardial necrosis was observed in cross-section of the heart (Fig. 3A). When the sites of myocardial necrosis were mapped, myocardial necrosis was found to be distributed in the entire circumference and all layers of the left ventricle (Fig. 3B). Microscopically, the myocardial necrosis was plurifocal (Fig. 3C) and contraction band necrosis (CBN) (Fig. 3D). Unlike myocardial infarction, intense eosinophilia of the cytoplasm of the myocardial fibers and nuclear pyknosis were not evident. There was no fibrosis; neither was there inflammation in the interstinum.

Fig. 3.

(A) Cross-section of the heart; (B) distribution of the myocardial necrosis sites; (C) the specimen from the left ventricle (hematoxylin–eosin staining; scale bar, 200 μm). The enclosed areas show the pleurifocal myocardial necrosis. (D) Area of contraction band necrosis in a left ventricle myocardium section, cellular degeneration typical of Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (hematoxylin-eosin staining; scale bar, 50 μm).

Discussion

There are several reports of TTC after pacemaker implantation 2, 3. It has therefore been proposed that TTC should be considered a potential complication of pacemaker implantation [2]. Kurisu et al. [2] reported two cases of TTC after pacemaker implantation, both in elderly female patients who received a dual-chamber pacemaker for CAVB without complications. The first one developed chest discomfort 10 min after the operation. She was given furosemide for congestive heart failure (CHF). The second case developed orthopnea three days after the operation. She also had CHF which required furosemide. Mazurek et al. [3] also reported a TTC as a complication of pacemaker implantation in a male patient who received a dual-chamber pacemaker for CAVB. Shortly after the operation he complained shortness of breath. He also had CHF which required furosemide. All patients in previous reports had CHF, and their symptoms were relieved by diuretics. Compared with previous reports, the present case is the most severe case of TTC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of TTC presenting ventricular tachycardia after pacemaker implantation.

TTC usually occurs in postmenopausal women of an advanced age. Mazurek et al. [3] first reported a case of TTC after pacemaker implantation in a male. It has been reported that physical stress might be much more associated with the occurrence in male patients compared to female patients [1]. Physicians should recognize that this disorder can occur unexpectedly during medical examination or treatment.

The prognosis of TTC is generally favorable but can result in ventricular arrhythmias and cardiogenic shock [1]. The incidence of ventricular arrhythmias varies according to reports. This variation may be related to an underestimation of ventricular malignant arrhythmias in previous reports, because sudden cardiac death can be the first clinical presentation of TTC [4].

It has been reported that nifedipine CR has inhibitory effects on symptomatic attacks in patients with vasospastic angina [5]. Our patient was treated with nifedipine CR for hypertension. There was no ST-segment elevation on his ECG. Cardiac enzymes were normal in this case. Coagulation necrosis results from severe persistent ischemia in myocardial infarction [6], and post-ischemic stunned myocardium results from myocardial edema [7]. But such results were not observed in this case. As mentioned above, we speculate that the possibility of vasospastic angina is low in the present case.

Most patients with TTC who underwent myocardial biopsy have shown the same results: interstitial infiltrates consisting primarily of mononuclear lymphocytes and macrophages; myocardial fibrosis; and contraction bands with or without myocardial necrosis [8]. Extensive inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate and multiple foci of CBN have been described too [9]. The inflammatory changes and contraction bands distinguish TTC from coagulation necrosis, as seen in myocardial infarction resulting from coronary artery occlusion [8]. The myocardial histological changes in TTC resemble those seen in catecholamine cardiotoxicity in both animals and humans. These changes, which differ from those in ischemic cardiac necrosis, include CBN, neutrophil infiltration, and fibrosis [8]. CBN is typical of catecholamine cardiotoxicity, which is a form of myocyte injury that has been described in many clinical situations with catecholamine excess [10]. The idea that CBN is a result of direct catecholamine toxicity is based on experimental catecholamine infusion [10]. The lesion is visible within 5–10 min of perfusion in the presence of normal vessels and unrelated to ischemia [10]. Myocardial necrosis was plurifocal and CBN in this case. We made a diagnosis of TTC based on these findings.

Excess catecholamines cause intramyocellular calcium overload, and this overload causes delayed after-potentials [11]. Delayed after-potentials appear to be responsible for the onset of the ventricular tachycardia. We speculate that catecholamine cardiotoxicity caused ventricular tachycardia in this case.

It has been reported that CBN is visible within 5–10 min of catecholamine infusion [10]. Both fibrosis and inflammation in the interstinum were not unremarkable in this case. Infiltration of inflammatory cells was observed 6 h after myocardial infarction [6]. Pathological findings suggested that CBN was caused at a very early phase of the onset of TTC and ventricular tachycardia also occurred simultaneously in this case.

In conclusion, we encountered a case of TTC presenting ventricular tachycardia after pacemaker implantation. Many and varied cases of TTC are reported. Further studies are needed to clarify the heterogeneity of this disease.

References

- 1.Kurisu S., Kihara Y. Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy: clinical presentation and underlying mechanism. J Cardiol. 2012;60:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurisu S., Inoue I., Kawagoe T., Ishihara M., Shimatani Y., Hata T., Nakama Y., Kijima Y., Kagawa E. Persistent left ventricular dysfunction in takotsubo cardiomyopathy after pacemaker implantation. Circ J. 2006;70:641–644. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazurek J.A., Gundewar S., Ji S.Y., Grushko M., Krumerman A. Left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome after pacemaker implantation in a male. J Cardiol Cases. 2011;3:e154–e158. doi: 10.1016/j.jccase.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonello L., Com O., Ait-Moktar O., Theron A., Moro P.J., Salem A., Sbragia P., Paganelli F. Ventricular arrhythmias during Tako-tsubo syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2008;128:e50–e53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.04.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oikawa Y., Matsuno S., Yajima J., Nakamura M., Ono T., Ishiwata S., Fujimoto Y., Aizawa T. Effect of treatment with once-daily nifedipine CR and twice-daily benidipine on prevention of symptomatic attacks in patients with coronary spastic angina pectoris-Adalat Trial vs Coniel in Tokyo against Coronary Spastic Angina (ATTACK CSA) J Cardiol. 2010;55:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antman E.M. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: pathology, pathophysiology, and clinical features. In: Braunwald E., editor. Heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 9th ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 2012. pp. 1092–1093. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bragadeesh T., Jayaweera A.R., Pascotto M., Micari A., Le D.E., Kramer C.M., Epstein F.H., Kaul S. Post-ischaemic myocardial dysfunction (stunning) results from myofibrillar oedema. Heart. 2008;94:166–171. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.102434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akashi Y.J., Goldstein D.S., Barbaro G., Ueyama T. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a new form of acute, reversible heart failure. Circulation. 2008;118:2754–2762. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.767012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wittstein I.S., Thiemann D.R., Lima J.A., Baughman K.L., Schulman S.P., Gerstenblith G., Wu K.C., Rade J.J., Bivalacqua T.J., Champion H.C. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fineschi V., Michalodimitrakis M., D’Errico S., Neri M., Pomara C., Riezzo I., Turrillazzi E. Insight into stress-induced cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac death due to stress. A forensic cardio-pathologist point of view. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;194:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pepe M., Zanna D., Quagliara D., Caiati C., Marzullo A., Palmiotto A.I., Caruso G., Favale S. Sudden cardiac death secondary to demonstrated reperfusion ventricular fibrillation in a woman with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2011;20:254–257. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]