Abstract

A 70-year-old woman with back pain and breathlessness was referred to our hospital for suspected myocardial infarction. Coronary angiogram was normal and endomyocardial biopsy showed inflammatory cell infiltrates consisting of eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells. The clinical course was hemodynamically fulminant, but steroid therapy improved the cardiac function. Interestingly, this patient had a past history of sarcoidosis. We diagnosed this case with idiopathic giant cell myocarditis (IGCM) from its clinical course. However, whether IGCM and cardiac sarcoidosis belong to the same histological entity has been debated. This case is important with respect to the pathogenic association between these two disorders.

<Learning objective: Both idiopathic giant cell myocarditis and cardiac sarcoidosis are known to show multinucleated giant cell infiltration in the myocardium histologically. In particular, idiopathic giant cell myocarditis is a severe and fulminant disease, making its early diagnosis and treatment important. Although it is difficult to diagnose these diseases, endomyocardial biopsy is useful to decide the treatment strategy in such disorders that may assume a fulminant course.>

Keywords: Idiopathic giant cell myocarditis, Cardiac sarcoidosis, Eosinophilic myocarditis, Endomyocardial biopsy, Multinucleated giant cell, Fulminant myocarditis

Introduction

Myocarditis exhibits a wide spectrum of signs and symptoms, and clinical outcomes range from asymptomatic to fatal [1]. Of these, idiopathic giant cell myocarditis (IGCM), which is a rare condition characterized by multinucleated giant cell infiltration and extensive myocardial cell necrosis, has an especially poor prognosis. Cooper et al. reported that the median transplant-free survival from symptom onset of this disease was only 5.5 months [2]. Meanwhile, cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) is known to also show multinucleated giant cell infiltration in the myocardium histologically [3], and therefore there has been discussion as to whether or not these two diseases belong to the same entity [1]. We experienced a patient who had a past history of sarcoidosis, and in whom IGCM was strongly suspected early in the clinical course.

Case report

A 70-year-old woman experienced sudden thoracodorsal pain 10 days before presentation and complained of gradually worsening breathlessness. Vomiting and dyspnea on effort had worsened beginning 3 days before presentation. She consulted her family physician who then referred her to our hospital after a diagnosis of heart failure due to myocardial infarction. Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy was observed on chest plain computed tomography 10 months prior to the onset of the current illness (Fig. 1A), and prior to that an ophthalmologist had noted uveitis. From both of these conditions, she was thought to suffer from sarcoidosis (extra-cardiac), and was followed up conservatively. The lymph nodes appeared to shrink without any medication (Fig. 1B). Her height was 144 cm, weight 40 kg, and there were neither risk factors for coronary artery disease nor any other relevant past history. On physical examination, her complexion was pale and she was afebrile. Her blood pressure was 122/69 mmHg, and she was tachycardic with a pulse of 132 bpm. On chest auscultation, coarse crackles were noted in the lung fields. There were no murmurs. Blood tests revealed elevated levels of troponin I (6.197 ng/mL), white blood cells (WBC: 8340/μL), lactate dehydrogenase (916 IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase (152 IU/L), creatine kinase (2924 IU/L), and creatine kinase-MB (80.9 ng/mL). The eosinophil count was not increased (1.1% of WBC). Brain natriuretic peptide was 4500 pg/mL. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (7.2 U/L), IgG (1427 mg/dL), IgA (260 mg/dL), and IgM (59 mg/dL) were not elevated. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus tachycardia, with low voltage in the limb leads, and a QS pattern in leads III, aVF, and V1–4 (Fig. 1C). Chest radiography showed bilateral pulmonary congestion and cardiomegaly (cardiothoracic ratio 58%) (Fig. 1D). Both ventricles had diffuse hypokinetic motion (ejection fraction of left ventricle was 20%) with no mitral regurgitation and respiratory variation of inferior vena cava on ultrasound cardiography. Emergent coronary angiography was performed due to suspected acute coronary syndrome, but revealed normal coronary arteries, while a left ventriculogram showed diffuse severe hypokinesis. The mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was 31 mmHg and the cardiac index was 1.5 L/min/m2. Under a provisional diagnosis of acute myocarditis associated with severe heart failure, an endomyocardial biopsy was performed from the posterior wall of the left ventricle, after which intra-aortic balloon pumping was initiated. Although her appearance and symptoms improved dramatically for a short while with intra-aortic balloon pumping support, a pale complexion, coldness of the extremities, and severe nausea gradually became evident. On the 3rd day ventricular tachycardia occurred frequently, and it became difficult to maintain her blood pressure, and so percutaneous cardiopulmonary support was commenced. Taking into consideration the possibility of fulminant viral myocarditis, gamma globulin (1 g/day) was administered for 4 days beginning on day 3 (total, 4 g). On the 5th day, an ECG showed advanced atrioventricular block and disappearance of the QRS complex. The results of endomyocardial biopsy obtained on the same day verified the presence of inflammatory cell infiltrates consisting mainly of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and multinucleated giant cells in the myocardial tissue. Marked fibrosis was also observed (Fig. 2A, B). Immunostaining with Propionibacterium acnes specific monoclonal antibodies (PAB antibody) of this biopsy specimen was negative for inflammatory lesions (Fig. 2C). From the clinical course and histological findings, IGCM, CS, and eosinophilic myocarditis were considered as the differential diagnosis, and steroid pulse therapy (methylprednisolone; mPSL 1 g/day) was started. Immediately thereafter restoration of sinus rhythm on the ECG monitor and left ventricular contraction on the echocardiogram were seen. After 3 days of steroid pulse therapy, steroid administration was continued (mPSL 40 mg/day for 4 days; prednisolone 20 mg/day for 7 days, and then reduced to 10 mg/day). Cyclosporine (200 mg/day) was started on day 6. Amiodarone was also given as an antiarrhythmic agent. Subsequently, the cardiac function gradually improved, and under inotropic support she was weaned from percutaneous cardiopulmonary support on the 12th day, and from intra-aortic balloon pumping on the 14th day. Since the pulmonary artery pressure then increased, hepatic function deteriorated, and urine volume decreased, phosphodiesterase type 3 inhibitor, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor administration and continuous hemodiafiltration were added to control her heart failure. Despite these interventions she developed ventilator-associated pneumonia. Although echocardiography showed improved left ventricular wall kinesis with an ejection fraction of approximately 30% and somehow the patient became hemodynamically stable, she died on the 39th day due to respiratory failure caused by acute respiratory distress syndrome.

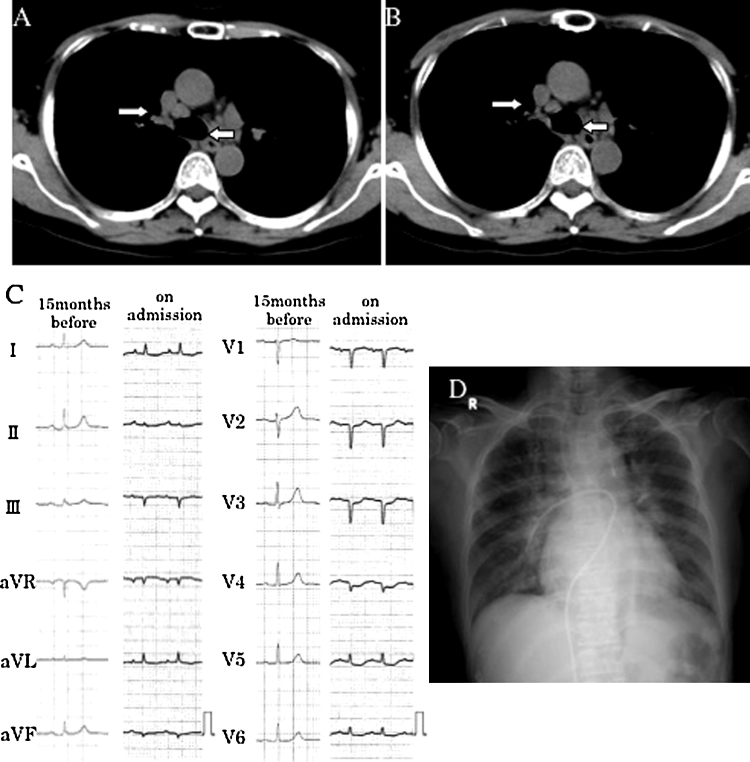

Fig. 1.

Chest plain computed tomography 10 months before admission shows swollen mediastinal lymph nodes (white arrows) (A). Their size subsequently decreased spontaneously without medication (B). Comparison of electrocardiogram (ECG) on admission with that of 15 months earlier (C) and chest radiography on admission (D). ECG on admission shows low voltage in the limb leads and QS pattern in leads III, aVF, and V1–4, indicating extensive myocardial damage. Chest radiography obtained after cardiac catheterization showed bilateral pulmonary congestion and cardiomegaly.

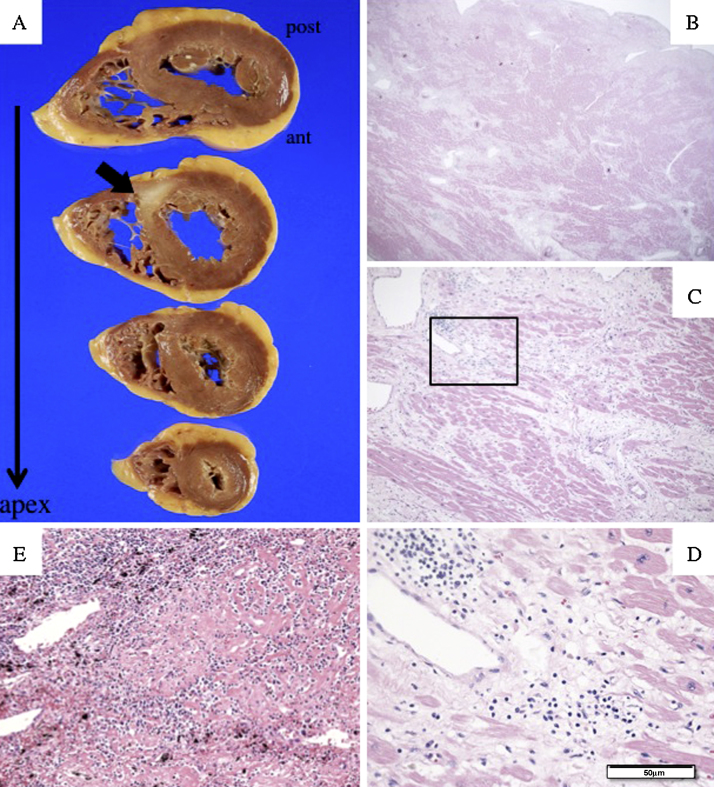

Fig. 2.

Histological findings of endomyocardial biopsy specimen. Marked myocardial fibrosis (A) with inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and eosinophils can be seen (B). Also, infiltration by multinucleated giant cells is evident (black arrow) (hematoxylin–eosin stain, A: 40×; B: 200×). Immunostaining with Propionibacterium acnes-specific monoclonal antibodies in inflammatory lesions was negative (C). If positive, brown and small round bodies should be seen in some of the inflammatory cells. The pictures on the left side show hematoxylin–eosin stained specimens, and those on the right immunostained ones (upper slide: 40×; lower slide: 200×).

Autopsy findings included a heart weight of 275 g, and a white cicatricial lesion from the posterior side of the ventricular septum to the posterior wall of the left ventricle (Fig. 3A), with cardiomyocytes replaced by collagen fibers throughout the heart (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). No eosinophils or multinucleated giant cells were found (Fig. 3C, D) and no findings suggestive of sarcoidosis such as the presence of epithelioid cells in the bronchopulmonary lymph nodes and lungs were detected (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Autopsy findings. A white cicatricial lesion can be seen extending from the posterior side of the ventricular septum to the posterior wall of the left ventricle (A). Histological findings in the myocardium of the left ventricle revealed widespread replacement of cardiomyocytes with collagen fibers, and interstitial edema in which only lymphocytes, but no eosinophils or multinucleated giant cells were present. In the bronchopulmonary lymph nodes, there were no findings suggestive of sarcoidosis such as the presence of epithelioid cells (E) (hematoxylin–eosin stain, B: 20×; C: 50×; D: 200×; E: 200×).

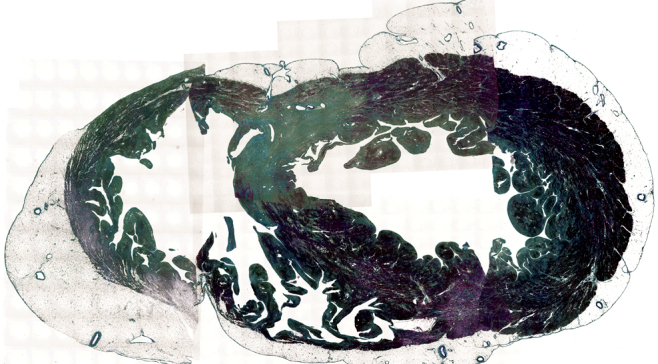

Fig. 4.

Panorama-view (microphotographs of the horizontal sections of the whole ventricles) at the level of cicatricial lesion in Fig. 3 (azan stain). These pictures represent global and transmural replacement of cardiomyocytes with fibrosis in the walls of both ventricles. The cardiomyocyte was stained red and the fibrosis was green in this specimen.

Discussion

The present case showed acute myocarditis that assumed a rapid course and pathologically revealed marked myocardial fibrosis, eosinophil infiltration, and the presence of multinucleated giant cells. We diagnosed this case as IGCM based on both the pathological findings and clinical course, discriminating it from CS and eosinophilic myocarditis.

Karatolios et al. recommended endomyocardial biopsy be performed early to diagnose this type of severe myocarditis [4]. Also in this case, the endomyocardial biopsy was useful, because its findings suggested the above-noted possible types of myocarditis as the differential diagnosis, which prompted us to administer a steroid.

IGCM is a rare and highly fatal disorder – the mean survival period from onset is a mere 5.5 months [2], and is characterized by multifocal inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes, eosinophils, and multinucleated giant cells and evident myocardial cell necrosis in association with the inflammatory lesion [5]. The etiology of IGCM is still unclear, but is often surmised to be autoimmune. Immunosuppressive treatment comprising cyclosporine, steroid pulse, and antithymocyte globulin (muromonab-CD3) is considered to be effective [2], [6]. Therefore we administered cyclosporine in addition to steroid pulse therapy in this case.

Interestingly, there was a past history of sarcoidosis in this case. The etiology of sarcoidosis is also poorly understood, but most likely involves some antigens, initiating an immune response [5]. Recently, Negi et al. reported that P. acnes might be the cause of granuloma formation in many sarcoid patients from their immunohistochemical approach with PAB antibody [7]. Using the biopsy sample, we obtained a negative result of the immunostaining with PAB antibody in some active inflammatory lesions. Although this did not fully exclude the possibility of CS, the lesions were probably not derived from pathological activity of sarcoidosis.

Since histologically multinucleated giant cell infiltration is found in both IGCM and CS, whether they are related conditions or not remains a topic of debate [1], [8], [9]. For instance, in two studies using mice, the possibility was raised that the immunological reactions in IGCM and CS are similar [8], [9]. Both experimental autoimmune myocarditis and sarcoidosis are associated with CD4-positive T cells with a T helper type 1 response, secretion of interleukin-2 and interferon-gamma, followed by fibrous hyperplasia and tissue scarring facilitated by T helper type 2 cells.

On the other hand, Okura et al. [1] revealed various histologic and clinical differences between IGCM and CS. They described that eosinophils, myocyte damage, and foci of lymphocytic myocarditis are more frequent in IGCM, while granulomas and fibrosis are more frequent in CS. Presentation with heart failure predicted IGCM, while that with atrioventricular block or a symptomatic period exceeding nine weeks predicted CS. Since in our case the patient had severe heart failure and marked myocardial damage and eosinophil infiltration were evident histologically, we diagnosed this case as IGCM.

In addition to the IGCM, eosinophilic myocarditis is known as a disease characterized histologically by eosinophil and lymphocyte infiltration corresponding to foci of myocardial necrosis and fibrosis, and the presence of multinucleated giant cells limited to fibrotic portions [10], [11]. A number of reports have described the efficacy of steroid administration in this disease [11]. Because the patient responded to steroids well, eosinophilic myocarditis had to be included in the differential diagnosis. However, given that an extremely rapid course was assumed from onset, the possibility of IGCM was considered to be higher than that of eosinophilic myocarditis.

Ten months prior to the onset of the current illness, this patient had been diagnosed with sarcoidosis based only on bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy detected on chest computed tomography and a history of uveitis. As far as we know, she did not undergo any other examinations to confirm the diagnosis of sarcoidosis or to detect CS (such as echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging, or fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography), but the white cicatricial lesion found in her autopsy heart, which is frequently observed in CS [12], is one piece of evidence suggestive of cardiac involvement by sarcoidosis 10 months previously. In addition, we had little chance to use cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with delayed enhancement or fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography because of the intensive care required in this case. Consequently, there was no positive proof to clarify any association with past sarcoidosis except some specimens of endomyocardial biopsy.

We have presented this case in detail because it may be of interest when considering the significance of appearances of multinucleated giant cells and the pathogenic association between these disorders.

Although this is the first report of IGCM with a past history of extra-cardiac sarcoidosis, their relationship is still unclear. Many more such cases will have to be collected before the pathophysiology of these two disorders can be better defined.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Okura Y., Dec G.W., Hare J.M., Kodama M., Berry G.J., Tazelaar H.D., Bailey K.R., Cooper L.T. A clinical and histopathologic comparison of cardiac sarcoidosis and idiopathic giant cell myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:322–329. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper L.T., Jr., Berry G.J., Shabetai R. Idiopathic giant-cell myocarditis: natural history and treatment. Multicenter Giant Cell Myocarditis Study Group Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1860–1866. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706263362603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yazaki Y., Isobe M., Hiramitsu S., Morimoto S., Hiroe M., Nakano T., Saeki M., Izumi T., Sekiguchi M. Comparison of clinical features and prognosis of cardiac sarcoidosis and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:537–540. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karatolios K., Pankuweit S., Maisch B. Diagnosis and treatment of myocarditis: the role of endomyocardial biopsy. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2007;9:473–481. doi: 10.1007/s11936-007-0042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habersberger V., Manins V., Taylor J. Cardiac sarcoidosis. Intern Med J. 2008;38:270–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper L.T., Jr., Hare J.M., Tazelaar H.D., Edwards W.D., Starling R.C., Deng M.C., Menon S., Mullen G.M., Jaski B., Bailey K.R., Cunningham M.W., William G. Usefulness of immunosuppression for giant cell myocarditis. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:1535–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Negi M., Takemura T., Guzman J., Uchida K., Furukawa A., Suzuki Y., Iida T., Ishige I., Minami J., Yamada T., Kawachi H., Costabel U., Eishi Y. Localization of Propionibacterium acnes in granulomas supports a possible etiologic link between sarcoidosis and the bacterium. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1284–1297. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okura Y., Yamamoto T., Goto S., Inomata T., Hirono S., Hanawa H., Feng L., Wilson C.B., Kihara I., Izumi T., Shibata A., Aizawa Y., Seki S., Abo T. Characterization of cytokine and iNOS mRNA expression in situ during the course of experimental autoimmune myocarditis in rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:491–502. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moller D.R., Forman J.D., Liu M.C., Noble P.W., Greenlee B.M., Vyas P., Holden D.A., Forrester J.M., Lazarus A., Wysocka M., Trinchieri G., Karp C. Enhanced expression of IL-12 associated with Th1 cytokine profiles in active pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Immunol. 1996;156:4952–4960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Getz M.A., Subramanian R., Logemann T., Ballantyne F. Acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis as a manifestation of severe hypersensitivity myocarditis. Antemortem diagnosis and successful treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:201–202. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-3-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe N., Nakagawa S., Fukunaga T., Fukuoka S., Hatakeyama K., Hayashi T. Acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis successfully treated by high dose methylprednisolone. Jpn Circ J. 2001;65:923–926. doi: 10.1253/jcj.65.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsui Y., Iwai K., Tachibana T., Fruie T., Shigematsu N., Izumi T., Homma A.H., Mikami R., Hongo O., Hiraga Y., Yamamoto M. Clinicopathological study on fatal myocardial sarcoidosis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1976;278:455–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb47058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]