Abstract

Anomalous origin of the right coronary artery (ARCA) from the main pulmonary artery is a rare congenital anomaly, unlike the well-known anomalous origin of the left coronary artery (Bland–White–Garland syndrome) from the pulmonary artery. Since most ARCA cases are diagnosed during childhood, few adult cases have been reported. We describe the case of a patient who demonstrated ventricular arrhythmia and low cardiac function due to ischemic heart disease and an ARCA. Coronary angiography revealed flow from the left coronary artery to the pulmonary artery via an epicardial collateral artery and the right coronary artery. Multidetector-row computed tomography provided a definitive diagnosis of ARCA; the patient underwent surgical revascularization.

<Learning objective: We incidentally diagnosed ARCA in a patient who experienced ventricular fibrillation. ARCA is a rare condition caused by early-onset cardiac ischemia, which may be a differential diagnosis for this congenital anomaly. Multidetector-row computed tomography is useful for detecting ARCA and determining the coronary artery's course and other congenital anomalies. Immediate surgical treatment for ARCA is strongly recommended to prevent sudden cardiac death.>

Keywords: Anomalous origin of the right coronary artery, Bland–White–Garland syndrome, Coronary angiography, Multidetector-row computed tomography

Introduction

Anomalous origin of the right coronary artery (ARCA) from the main pulmonary artery is a rare congenital anomaly, with an estimated prevalence of 0.002% [1], and is attributed to a developmental anomaly of the aortic septum. Anomalies such as aortopulmonary window, tetralogy of Fallot, and septal defects have been reported in 22% of ARCA patients [2]. Most ARCA patients are diagnosed during childhood with congestive heart failure, or the diagnosis is missed because of asymptomatic status. However, ARCA patients are at a risk of sudden cardiac death. Therefore, surgical treatment is strongly recommended, even for asymptomatic patients [3]. In this report, we present the case of an adult patient who presented with ventricular fibrillation and was diagnosed with ARCA.

Case report

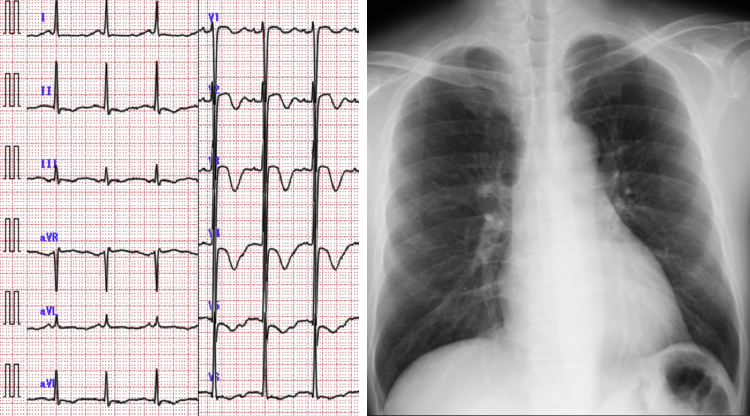

A 44-year-old man, without a significant medical history, was brought to our hospital by ambulance because of loss of consciousness and a seizure after consuming alcohol. The patient did not have a personal or family history of syncope and did not have a family history of sudden death. The patient regained consciousness in the emergency room, but suffered from retrograde amnesia. Upon examination, his blood pressure and heart rate were 154/60 mmHg and 100 beats/min, respectively; he did not exhibit any extra heart sounds, murmurs, neck vein distension, or pedal edema. Laboratory data showed elevated B-type natriuretic peptide (296 pg/mL) and low potassium (3.2 mequiv./L) levels. An electrocardiogram demonstrated an inverted T-wave in the anterior precordial lead and a corrected QT time, calculated using Bazett's correction, of 582 ms (heart rate, 86 beats/min). A chest radiograph did not reveal cardiomegaly or congestion (Fig. 1), but transthoracic echocardiography showed diffuse hypo-contraction, without asynergy, and left ventricular enlargement.

Fig. 1.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) and chest radiograph. The patient's ECG demonstrated inverted T-waves in the anterior precordial lead and a corrected QT time of 582 ms (heart rate, 86 beats/min).

We speculated that the patient was suffering from Adams–Stokes syndrome, based on his ventricular arrhythmia, and admitted him for monitoring. Ventricular fibrillation occurred during the night of admission, and was terminated using electrical defibrillation. The ventricular arrhythmia was believed to be secondary to hypokalemia, and further episodes were prevented by correcting the patient's serum potassium level by immediately infusing a potassium supplement. The next day, the inverted T-wave in the anterior precordial lead was normalized.

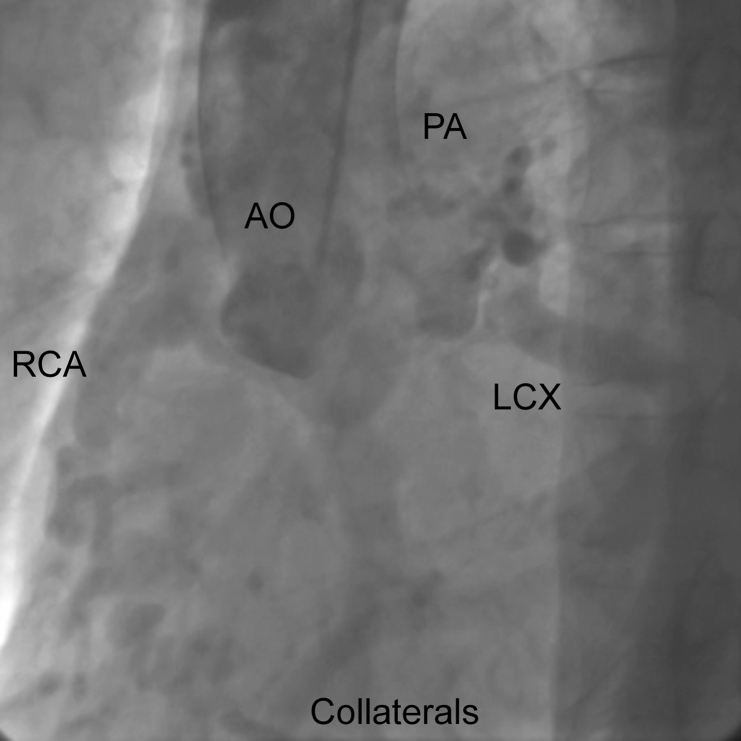

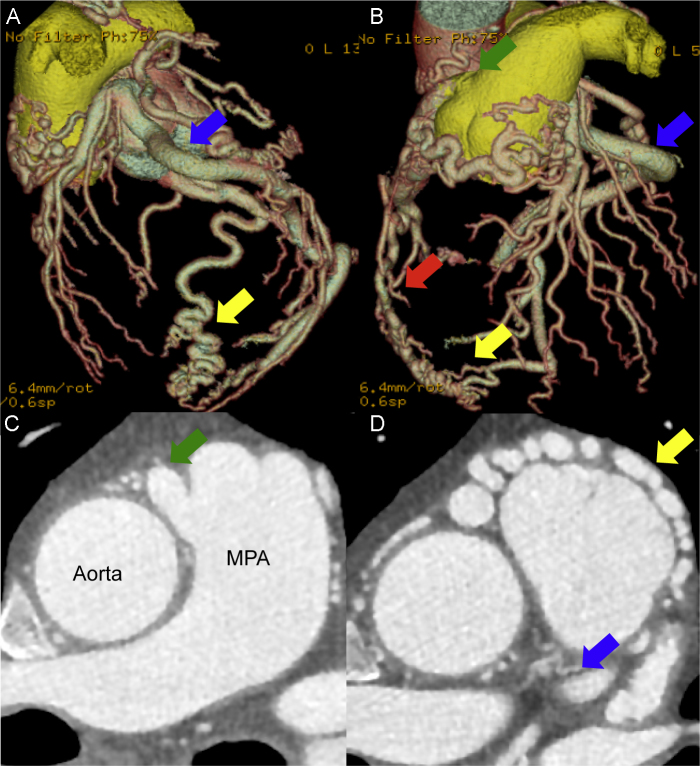

Coronary angiography (CAG) was performed because of the suspicion of ischemic heart disease. However, CAG of the left coronary artery (LCA), using a 5-Fr Judkins catheter and a normal amount of contrast, did not yield clear results. Therefore, a 5-Fr pigtail catheter was used, with a large amount of contrast being mechanically injected to reveal flow from the LCA to the pulmonary artery via an epicardial collateral artery and the right coronary artery (RCA) (Fig. 2); right coronary cusp injection did not show the RCA. His left ventriculogram showed diffuse hypokinesis with an end diastolic volume of 164 mL and an ejection fraction of 33%. Multidetector-row computed tomography (MDCT) was performed to precisely evaluate the angiectopia. 3D imaging showed the coronary artery's course, 2D imaging showed the drainage point of RCA from the pulmonary artery and the collateral artery with rich flow to the RCA from the left coronary artery (Fig. 3). MDCT provided a definitive ARCA diagnosis.

Fig. 2.

Coronary angiography. LCX, left circumflex artery; RCA, right coronary artery; AO, aorta; PA, pulmonary artery.

Fig. 3.

Multidetector-row computed tomography. (A) Left anterior oblique view. (B) Anteroposterior view. (C) The drainage point of right coronary artery from the pulmonary artery. (D) The collateral artery with rich flow to the right coronary artery from the left coronary artery. Left circumflex artery (blue arrow), collateral artery (yellow arrow), right coronary artery (red arrow), and ostium of the right coronary artery (green arrow). The red artery is the aorta; the yellow vessel is the pulmonary artery. MPA, main pulmonary artery.

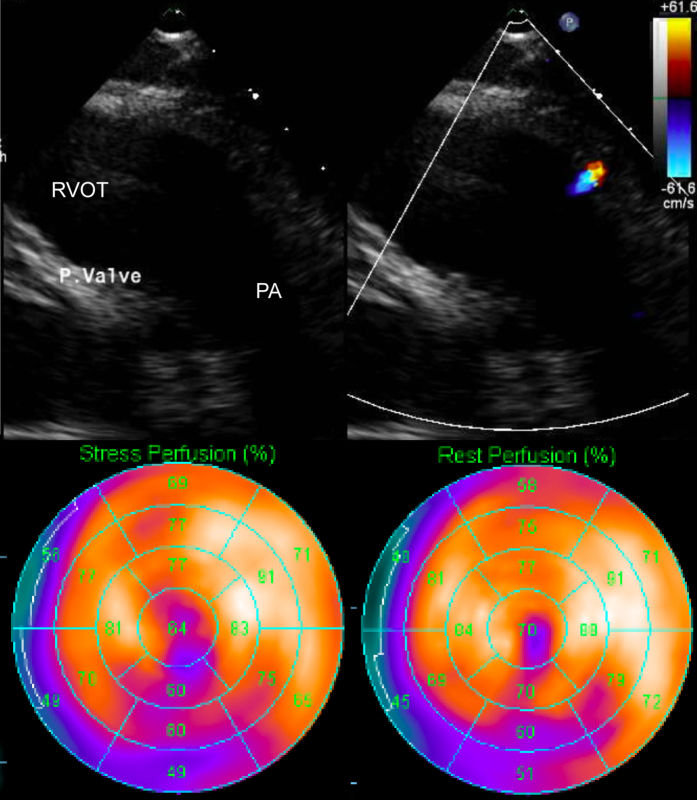

Re-examination of the patient's transthoracic echocardiogram showed the RCA orifice in the pulmonary artery and flow acceleration. Pharmacologic stress perfusion scintigraphy imaging showed infarct and ischemia of the inferior and apical walls (Fig. 4); cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed diffuse hypokinesis, but no late gadolinium enhancement. The myocardial ischemia was considered to have been caused by a low cardiac function and provided the setting for the ventricular arrhythmia. Several tests confirmed the viability of the myocardium, and we immediately performed surgery to move the RCA origin to the ascending aorta to prevent the risk of sudden cardiac death.

Fig. 4.

Transthoracic echocardiography and stress perfusion scintigraphy. The top panel shows the orifice of right coronary artery at the pulmonary artery and flow acceleration. The bottom panel shows a myocardial infarct and ischemia of the inferior and apical walls. RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; PA, pulmonary artery.

Discussion

The anomalous origin of the LCA from the pulmonary artery is common and is referred to as Bland-White-Garland (BWG) syndrome. This condition arises as a dysplasia of the aortic septum that separates the truncus arteriosus into the aorta and pulmonary artery [2], and represents 0.24% of all congenital cardiac disease. BWG syndrome has four stages. The first stage occurs during fetal life, manifesting as antegrade flow from the pulmonary artery to the coronary artery because of high pulmonary artery pressure. The second stage occurs during the early postnatal period when the patient develops ischemia and heart failure due to low cardiac perfusion caused by a reduction in pulmonary artery pressure without rich collateral artery flow. The third stage, during early adult life, demonstrates good cardiac perfusion via rich collateral artery flow from the contralateral coronary artery. The last stage, during late adult life, involves the overloaded collateral artery causing recurrent ischemia because of the steal phenomenon from the RCA to the LCA and pulmonary artery.

The anomalous origin of the RCA from the pulmonary artery is a rare condition with only 98 cases having been reported in the literature [4]; its small perfusion area results in the patient generally being asymptomatic, compared with patients having BWG syndrome. However, the coronary steal phenomenon, from the LCA to the RCA and pulmonary artery, triggers extensive cardiac ischemia and causes ventricular arrhythmia, similar to the last stage of BWG syndrome [5]. The clinical symptoms depend on the severity of the collateral flow from the LCA, often making the diagnosis of this condition difficult. Fortunately, MDCT is a useful modality for diagnosing this congenital defect [6]. Patients not undergoing surgical treatment for this anomaly typically have a short lifespan; therefore, immediate surgical treatment, as soon as the condition is diagnosed, is strongly recommended [7].

In conclusion, we treated a patient presenting with ventricular fibrillation who was incidentally diagnosed with ARCA arising from the pulmonary artery. ARCA should be included as a differential diagnosis for early-onset cardiac ischemia. MDCT, Doppler cardiac echography, and scintigraphy are useful for detecting an ARCA, determining the coronary artery's course, and demonstrating the patient's degree of ischemia. Immediate surgical treatment is strongly recommended for patients with this congenital condition to minimize the risk of sudden death.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Williams I.A., Gersony W.M., Hellenbrand W.E. Anomalous right coronary artery arising from the pulmonary artery: a report of 7 cases and a review of the literature. Am Heart J. 2006;152(1004):e9–e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brouwer M.H., Beaufort-Krol G.C., Talsma M.D. Aortopulmonary window associated with an anomalous origin of the right coronary artery. Int J Cardiol. 1990;28:384–386. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(90)90327-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radke P.W., Messmer B.J., Haager P.K., Klues H.G. Anomalous origin of right coronary artery: preoperative and postoperative hemodynamics. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:1444–1449. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00716-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuba P.K., Sharma J., Sharma A. Successful surgical treatment of a septuagenarian with anomalous right coronary artery from the pulmonary artery with an eleven year follow-up: case report and review of literature. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013;13:169–174. doi: 10.12816/0003215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baue A.E., Baum S., Blakemore W.S., Zinsser H.F. A later stage of anomalous coronary circulation with origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: coronary artery steal. Circulation. 1967;36:878–885. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.36.6.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ichikawa M., Lim Y.J., Komatsu S., Iwata A., Ishiko T., Sato Y., Hirayama A., Kodama K., Mishima M. Detection of Bland–White–Garland Syndrome by multislice computed tomography in an elderly patient. Int J Cardiol. 2007;114:288–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.11.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodge-Khatami A., Mavroudis C., Backer C.L. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: collective review of surgical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:946–955. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]