Abstract

Objective:

To describe the clinical outcomes associated with the use of checkpoint inhibitor therapy in recurrent ovarian malignancy.

Methods:

Women with recurrent ovarian cancer treated with an immune checkpoint inhibitor between 1/2012 and 8/2017 were included. RECIST criteria determined disease status, and immune related adverse events (irAE) were graded per trial protocols. Predictors of response, irAE, progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were investigated.

Results:

Forty-four women were included with a median age of 53 years, median of 4 prior lines of chemotherapy, and most commonly high grade serous pathology (59.1%). 3 patients had partial response and 3 had pseudoprogression, for a response rate of 14.2%. In subset analysis of high grade serous (HGSOC) pathology, platinum sensitivity at time of checkpoint inhibitor therapy was correlated with response (p=0.01). There were 28 grade 3/4 irAEs in 21 patients (47.7%). Combination therapy rather than monotherapy predicted irAE (OR 5.7, CI 1.6–20.9, p=0.02). The most common severe irAE was elevation in hepatic or pancreatic enzymes in 12 total patients (13.6% each). Interestingly, the number of genes mutated was protective from hepatic/pancreatic AE (p=0.02).

Conclusions:

While response rate was similar to prior literature, in patients with HGSOC platinum sensitivity at time of checkpoint inhibitor initiation was correlated to response. Grade 3/4 hepatic and pancreatic enzyme elevations were more common in ovarian cancer patients than has been previously reported in other tumorfd types. The number of genes mutated was inversely correlated to risk of this type of irAEs but not to total irAEs.

Background

While the traditional management of advanced stage ovarian cancer with tumor reductive surgery and adjuvant platinum-taxane chemotherapy results in high rates of complete response, the vast majority of patients recur. These patients are considered incurable, and, since the FDA’s approval of cisplatin and paclitaxel combination in 1998, there has been no regimen that has uniformly improved overall survival (OS) over existing therapy. Most cytotoxic and biologic agents result in only modest rates of response, with a median progression free survival (PFS) of 3 months for platinum resistant disease [1]. However, the recent advent of immunotherapy represents a new frontier.

In ovarian cancer, the infiltration of treatment naïve tumors with T-cells (TILs) was associated with a significantly improved median progression free (22.4 vs 5.8 months, p < 0.001) and overall survival (50.3 vs 18.0 months, p < 0.001) compared to tumors with no T-cells present, demonstrating the impact of the tumor immune microenvironment [2]. Additionally, expression of programmed-death ligands 1 and 2 (PD-L1 and PD-L2) has been shown to correlate with improved OS [3]. Clinically, checkpoint blockade and immune modulation have demonstrated impressive efficacy in multiple solid tumor types, resulting in FDA approvals for melanoma, non-squamous cell lung cancer, and urothelial carcinoma, among others [4], [5]. In ovarian cancer, phase Ib-II trials report objective response rates ranging from 6–15%, while disease control rates are variable but can reach as high as 45% [6]–[8]. Though small in overall number, the presence of responses in these often heavily pretreated patients is encouraging and has prompted multiple ongoing further investigations, with a particular focus on combination regimens [9]–[11]. These include not only immune checkpoint inhibition with standard chemotherapeutic agents but also various immunotherapy combinations[12][13].

Given this rapid expansion of trials and immunotherapy options available, dissemination of early experience with these therapies and reporting of outcomes is essential to inform further trials and research. The current study presents a retrospective review of all women at a single institution with recurrent ovarian malignancy treated on Phase I trials with checkpoint inhibitor therapy and reports clinical outcomes and toxicity.

Materials and Methods

The Institute for Personalized Cancer Therapy (IPCT) and Department of Investigational Cancer Therapeutics (ICT) at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center maintain a collaborative database (MOCLIA) of all patients enrolled in clinical trials within the department. This database was queried for all ovarian cancer, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer patients treated between 1/1/2012–8/1/2017. This resulted in 1011 patients, which were then limited by designation of having received immunotherapy, defined as any drug that primes the immune system against the tumor, which resulted in 187 patients. Individual chart review was then performed to ensure inclusion of only checkpoint inhibitor based therapies which resulted in the final cohort of 44 patients. Trial choice and enrollment was dependent on availability at clinic visit during the 5 year time period studied. While checkpoint inhibitor therapy was mandatory for inclusion, combinations with other drugs were also permitted.

Patient charts were reviewed for demographic variables including age at study enrollment, race, sex, tumor histology, platinum sensitivity, number of gene mutations, and prior therapies. Platinum sensitivity was defined both by initial tumor response as well as sensitivity at time of checkpoint therapy initiation. Number of genes mutated was determined by panel testing per individual clinical trial protocol, as all trials included required mutation assessment. Gene panel used varied by trial; panels included CMS50, Foundation One, Oncomine, STAG_V1, or Guardant360. The MOCLIA database reporting system includes a read out of genes mutated but abstracted data did not include granular information regarding number of mutations per megabase. Therefore, number of genes mutated was used as a proxy but does not provide an exact evaluation of overall mutation burden. In order to allow for comparison of gene mutations across gene panels utilized in included trials, gene number was also quantified using a common subset of 50 gene mutations (Appendix A1). Date of initiation of checkpoint inhibition, number of study treatment cycles and response based on imaging criteria were obtained. Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST V1.1) as well as irRC were used per respective clinical trial protocol to assess response [14]–[16]. Progression free and overall survival durations as well as last follow up was also recorded; progression free interval was defined as the duration between date of first dose of immune checkpoint inhibitor to date of documented progression on imaging or onset of clinical symptoms. Subsequent scans after progression were reviewed to avoid misclassification of pseudo-progression per trial protocol direction, and images were re-reviewed at time of the current study by radiology collaborator (RI) to confirm appropriate classification of disease response. Toxicities were graded based on National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE v4.0). Only severe toxicity, ie grade 3 or 4, was included in this analysis.

MD Anderson Institutional Review Board (IRB) independently approved each clinical trial presented within the current study; thus, per protocol, all patients provided informed consent prior to treatment with investigational therapy. MD Anderson IRB additionally approved retrospective review of the clinical trial data included within this study.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis consisted primarily of descriptive statistics such as means, medians, and measures of dispersion. Predictors of AE were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate for the measure. Predictors were screened for inclusion in the full multivariable regression using univariate regression; variable with no convergence issues and p <0.20 were included in the full model. Multivariate logistic regression with backwards stepwise selection was performed. Overall and progression free survival were visualized using Kaplan-Meier methodology and predictors of survival were tested using Cox regression. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Between January 1st, 2012 and August 1st, 2017 there were 44 patients with recurrent ovarian cancer enrolled on immune checkpoint inhibitor clinical trials within the Department of Investigational Cancer Therapeutics (ICT) at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. The clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. The median age was 53 years old (range 28–73) and the vast majority of patients were of white race (70.5%). Ovarian cancer pathology was most commonly high grade serous type (59.1%), but study also included patients with endometrioid (4.5%), clear cell (6.8%), mucinous (4.5%), germ cell or sex chord stromal tumors (11.4%), and low grade serous histologies (13.6%). The cohort was approximately split evenly between initially platinum sensitive (50%) and platinum resistant (45.5%) disease, with 2 patients with unknown sensitivity. Among those women with high grade serous pathology, only 7 patients remained platinum sensitive at time of checkpoint inhibitor therapy initiation. The median number of prior treatments was 4 (range: 1–10).

Table 1.

Patient demographics, clinical history, and trial treatment regimen

| Number of Patients (n=44) |

|

|---|---|

| Age (median, range) | 53 (28−73) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 31 |

| Black | 0 |

| Hispanic | 4 |

| Asian | 5 |

| Other/Unknown | 4 |

| Pathology | |

| High-grade serous | 26 |

| Endometrioid | 2 |

| Clear cell | 3 |

| Mucinous | 2 |

| Germ cell/Sex chord stromal | 5 |

| Low grade serous | 6 |

| Initial Platinum Sensitivity | |

| Yes | 22 |

| No | 20 |

| Unknown | 2 |

|

HGSOC Platinum Sensitivity at Time of Checkpoint Therapy

1 (N=26) |

|

| Yes | 7 |

| No | 19 |

| Number of prior treatments (median, range) | 4 (1−10) |

| Mutation number (median, range) | |

| Total mutation (all panels) | 2 (0−18) |

| Standardized 50 gene panel | 1 (0−5) |

| Investigational Therapies | |

| Combination | 28 |

| Monotherapy | 16 |

| Combination regimen | |

| Second Checkpoint inhibitor | 6 |

| Other immunomodulatory agent | 13 |

| Other targeted small molecule | 5 |

| Traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation | 4 |

| Checkpoint inhibitor (by mechanism) | |

| Anti-PD-1 | 25 |

| Anti-CTLA-4 | 6 |

| Anti-PD-L1 and Anti-CTLA-4 Combination | 5 |

| Anti-TIM3 | 6 |

| Other checkpoint inhibition | 2 |

Includes only high grade serous pathology, total N = 26. 17 of these patients were initially platinum sensitive.

The median number of genes mutated, regardless of which panel testing was performed, was 2 (range: 0–18). When genes were standardized to only those tested within the 50 gene panel, the median was 1 (range: 0–5). The most commonly mutated genes were TP53 and KRAS, which mirrors known most common mutations in epithelial ovarian cancer [17].

Treatment Regimen

Checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy made up 36.4% of the cohort, while the remainder of patients were treated with a combination regimen (Table 1). The type of checkpoint inhibition included anti-PD-1 in the majority of patients (56.8%) followed by anti-CTLA-4 (13.6%) and the combination of anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 (11.4%). Combination regimens included four main categories: use of second checkpoint inhibitor (21.4%), other immune effector (46.4%), other targeted small molecule (17.9%), and traditional chemotherapy or radiation (14.3%). The median number of on-trial cycles received was 4, with a range of 1 to 27 cycles.

Responses and Survival

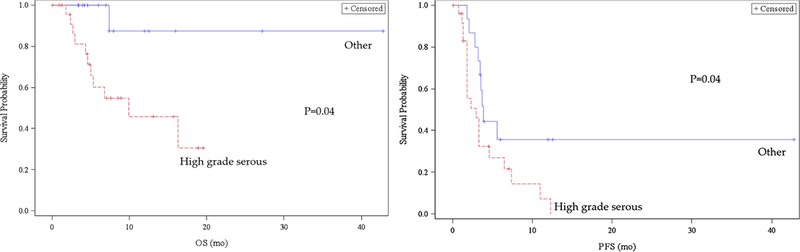

The median progression free survival for the entire cohort was 3.3 months following the initiation of checkpoint inhibitor therapy. In multivariate analysis, only high grade serous pathology independently predicted poorer PFS with median of 2.9 (HR=2.3, 95% CI 1.8–4.6) compared to 3.9 months (95% CI 2.8, n/a) (Figure 1). While surveillance strategies varied by trial, many included three month imaging thus the PFS reported is likely related to timing of first evaluation following trial initiation. High grade serous pathology was also associated with decreased overall survival compared to other histologies with a median survival of 9.9 months (95% CI 4.6, n/a) while median survival of other pathologies could not be estimated due to insufficient follow up (HR 8.5, lower estimate of 95% CI 7.4 months). Thirty-one patients remained alive at time of data abstraction, with an overall median of 5.98 months follow-up, compared to the 13 patients who died during analysis who had a median OS of 4.99 months.

Figure 1. Progression Free and Overall Survival by Histology.

Legend:PFS: Progression Free Survival OS: Overall Survival

Of the 39 patients with complete response imaging available, the best response demonstrated was partial response in 3 patients (7.7%). All of these women had high-grade serous pathology and two had platinum sensitive disease. Two of the patients received anti-PD-1 therapy in combination with other immune modulation, which included IDO-1 inhibitor and CXCR2 antagonist, while the third was enrolled on a combination checkpoint inhibitor trial including anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4. An additional 3 patients were found to have pseudoprogression (7.7%). Their pathology included high grade serous, mucinous, and low grade serous carcinoma. All three were treated with an anti-PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor, two as monotherapy and the third in combination with a small molecule targeting signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). Analysis was performed to determine predictors of response, including presence of severe adverse event, but none of the variables investigated demonstrated statistical significance in the total cohort (Table 2). However, among the subset analysis of high grade serous pathology, platinum sensitivity at time of checkpoint inhibitor therapy was predictive of response (p=0.01). Subsequent logistic regression demonstrated that the duration of platinum resistant disease was not significantly related (p = 0.5210). Given preliminary anecdotal evidence that clear cell pathology may have improved response rate to immune checkpoint, the three patient’s with this pathology were compared to the total cohort and did not demonstrate difference in response (p=0.01). Multivariate analysis, performed among only the HGSOC subset, demonstrated that platinum sensitivity at time of checkpoint initiation remained independently predictive (p = 0.0463).

Table 2.

Predictors of Response to Investigational Therapy

| Non-response (N = 33) |

Response1 (N = 6) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Pathology | 0.6790 | ||

| Non-Serous | 15 (45.5%) | 2 (33.3%) | |

| Serous | 18 (54.5%) | 4 (66.7%) | |

| Initial Platinum Sensitivity | 0.1250 | ||

| Yes | 15 (45.5%) | 4 (66.7%) | |

| No | 17 (51.5%) | 1 (16.7%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (3.0%) | 1 (16.7%) | |

| Investigational Therapy | 1.0000 | ||

| Monotherapy | 17 (51.5%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| Combination | 16 (48.5%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| Checkpoint inhibitor (by mechanism) | 0.5446 | ||

| Anti-PD-1 | 15 (45.5%) | 5 (83.3%) | |

| Anti-CTLA-4 | 6 (18.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Anti-PD-L1 and Anti-CTLA-4 Combination | 4 (12.1%) | 1 (16.7%) | |

| Anti-TIM3 | 6 (18.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other checkpoint inhibitor | 2 (6.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Presence of Severe AE | 1.0000 | ||

| No | 17 (51.5%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| Yes | 16 (48.5%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| Presence of Hepatic/Pancreatic Severe AE | 0.6450 | ||

| No | 22 (66.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | |

| Yes | 11 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | |

|

HGSOC Platinum Sensitivity at Time of Checkpoint Therapy (N = 22)2 |

N = 18 | N = 4 | 0.0100 |

| Yes | 1 (5.6%) | 3 (75.0%) | |

| No | 17 (94.4%) | 1 (25.0%) | |

Includes partial response and pseudoprogression

Includes only high grade serous pathology, 4 patients with missing information

Adverse Events

Adverse events (AE) as graded by CTCAE version 4.0 were limited to severe (grade 3 and 4) events. There were a total of 28 severe immune related adverse events in 21 patients (47.7% of the total cohort), 14 of whom required dose delays (66.7% of those with AE). As has been reported with checkpoint inhibitor use in other tumor types, the type of adverse event varied broadly, spanning multiple organ systems (Table 3). Hematologic toxicities, including anemia and neutropenia, were attributed to immune-related toxicity in 6 patients (13.6%) but 4 of which occurred in patients receiving some form of combination therapy.

Table 3.

Description of Severe (Grade 3 or 4) Adverse Events

| Frequency (number of events, %) Total patients: 44, Total events: 28 |

|

|---|---|

| Grade 3/4 Adverse Events | |

| Neurologic | 2 (4.6) |

| Cardiovascular | 2 (4.6) |

| Pulmonary | 3 (6.8) |

| Endocrine | 0 (0) |

| Hepatic | 6 (13.6) |

| Pancreatic | 6 (13.6) |

| Colitis | 2 (4.6) |

| Hematologic | 5 (11.4) |

| Dermatologic | 2 (4.6) |

The most common immune related AE was elevation in hepatic or pancreatic enzymes; 6 patients had hepatic elevations (13.6%) while an additional 6 patients had elevations in pancreatic enzymes (13.6%), or 27.2% overall. To confirm that these events were not related to disease burden in the liver, patients were classified into groups based on presence or absence of hepatic or perihepatic metastasis (non-parenchymal). The distribution of hepatic or pancreatic enzyme elevations was not significantly different between women with hepatic disease burden and those without (p=0.23). Additionally, there was no statistically significant temporal relationship found between types of AE; in particular, there was no evidence that hepatic or pancreatic enzyme elevations occurred earlier or later than other AE (p=0.8). The duration until peak hepatic or pancreatic enzyme elevation varied widely, with a median of 43 days (range 7–100).

Of these women with a grade 3/4 hepatic or pancreatic event, 92% (11 patients) received checkpoint inhibition in some form of combination regimen. Specifically, 3 patients (25%) received combination of two checkpoint inhibitors while an additional 7 patients received checkpoint inhibition and another immunomodulatory agent (58.3%). Only 1 patient (8.3%) received checkpoint inhibitor and radiation and 1 patient (8.3%) received checkpoint inhibitor alone. Only one patient had abnormal baseline labs and adverse event was graded based on rise, all other women had normal baseline AST, ALT, amylase, and lipase. Women with pancreatic enzyme elevations were more likely to be asymptomatic, while those with hepatic enzyme elevations presented with varying symptoms including most commonly abdominal pain and nausea/vomiting. All women with hepatic enzyme elevations stopped checkpoint inhibitor treatment at time of grade 3/4 event, compared to women with pancreatic enzyme elevations where half (3 patients) continued on treatment given their asymptomatic status. 2 women (16.6%) received steroids, both for hepatic enzyme elevations, while the remaining women had spontaneous downtrend of labs. Interestingly, half of women with a hepatic or pancreatic grade 3/4 event did receive subsequent checkpoint inhibitor (6 patients); of these women who continued or resumed treatment, 4 had pancreatic enzyme elevations while only 2 women with severe hepatic enzyme abnormalities continued treatment.

Clinical predictors of severe AE were then investigated. The use of immune checkpoint inhibitor as part of combination therapy rather than monotherapy was the only significant predictor of overall AE (Table 4, OR 7.8, CI 1.8–34.1, p=0.005). Given the comparatively high rates of hepatic and pancreatic related events, further investigation was performed into predictors of these specific AEs (Table 5). Multivariate analysis again demonstrated the significant increased risk with combination regimen for this specific subset of AEs (p=0.0097).

Table 4.

Predictors of Severe (Grade 3/4) Adverse Event

| No Grade 3/4 AE (N=23)1 |

Grade 3/4 AE (N=21)1 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Pathology | 0.3726 | ||

| Non-Serous | 11 (47.8%) | 7 (33.3%) | |

| Serous | 12 (52.2%) | 14 (66.7%) | |

| Initial Platinum Sensitivity | 1.0000 | ||

| Yes | 10 (43.5%) | 10 (47.6%) | |

| No | 12 (52.2%) | 10 (47.6%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (4.8%) | |

| Investigational Therapy | 0.0050 | ||

| Monotherapy | 13 (56.5%) | 3 (14.3%) | |

| Combination | 10 (43.5%) | 18 (85.7%) | |

| Checkpoint inhibitor (by mechanism) | 0.2692 | ||

| Anti-PD-1 | 12 (52.2%) | 13 (61.9%) | |

| Anti-CTLA-4 | 5 (21.7%) | 1 (4.8%) | |

| Anti-PD-L1 and Anti-CTLA-4 Combination |

2 (8.7%) | 3 (14.3%) | |

| Anti-TIM3 | 2 (8.7%) | 4 (19.0%) | |

| Other checkpoint inhibitor | 2 (8.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

|

HGSOC Platinum Sensitivity at Time of Checkpoint (N = 26)2 |

N=12 | N=14 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 3 (25.0%) | 4 (28.6%) | |

| No | 9 (75.0%) | 10 (71.4%) | |

| Mutation Panel Testing | |||

| 50 Gene Panel (N= 30)2 | 0.0795 | ||

| Mutation number (median, range) | 2 (0−5) | 1 (1−3) | |

| 134 Gene Panel (N = 15)3 | 0.1788 | ||

| Mutation number (median, range) | 4 (1−18) | 1 (1−9) | |

Total number of patients, not number of events

Includes only high grade serous pathology

Of the 30 patients who contributed mutation data within the 50 gene panel, 14 had a grade 3/4 AE while 16 did not.

Of the 15 patients who contributed mutation data within the 134 gene panel, 9 had a grade 3/4 AE while 6 did not.

Table 5.

Predictors of Severe (Grade 3/4) Hepatic or Pancreatic Adverse Event

| No AE (N=23)1 | Grade 3/4 Hepatic or Pancreatic AE (N=12)1 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Pathology | 0.1390 | ||

| Non-Serous | 11 (47.8%) | 2 (16.7%) | |

| Serous | 12 (52.2%) | 10 (83.3%) | |

| Initial Platinum Sensitivity | 1.0000 | ||

| Yes | 10 (43.5%) | 6 (50.0%) | |

| No | 12 (52.2%) | 6 (50.0%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Investigational Therapy | 0.0097 | ||

| Monotherapy | 13 (56.5%) | 1 (8.3%) | |

| Combination | 10 (43.5%) | 11 (91.7%) | |

| Checkpoint inhibitor (by mechanism) | 0.4555 | ||

| Anti-PD-1 | 12 (52.2%) | 8 (66.7%) | |

| Anti-CTLA-4 | 5 (21.7%) | 1 (8.3%) | |

| Anti-PD-L1 and Anti-CTLA-4 Combination |

2 (8.7%) | 3 (25.0%) | |

| Anti-TIM3 | 2 (8.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other checkpoint inhibitor | 2 (8.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Hepatic/Perihepatic Metastasis | 0.23 | ||

| Yes | 22 (68.8%) | 5 (41.7%) | |

| No | 10 (31.2%) | 7 (58.3%) | |

|

HGSOC Platinum Sensitivity at Time of Checkpoint (N = 19)2 |

N= 8 | N= 11 | 0.2451 |

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 3 (27.3%) | |

| No | 8 (100%) | 8 (72.7%) | |

| Mutation Panel Testing | |||

| 50 Gene Panel (N= 30)3 | 0.0156 | ||

| Mutation number (median, range) | 2 (0–5) | 1 (1) | |

| 134 Gene Panel (N = 15)4 | 0.0236 | ||

| Mutation number (median, range) | 4 (1–18) | 1 (1) | |

Total number of patients, not number of events

Includes only high grade serous pathology.

Of the 30 patients who contributed mutation data within the 50 gene panel, 10 had a grade 3/4 hepatic or pancreatic AE while 20 did not.

Of the 15 patients who contributed mutation data within the 134 gene panel, 7 had a grade 3/4 hepatic or pancreatic AE while 8 did not.

When the number of genes mutated was analyzed as a continuous variable and compared to patients without an adverse event, the number was associated with lower risk of experiencing a hepatic or pancreatic AE (p=0.02). This was unique to this specific subset of adverse events; there was no association with any other type of AE individually (all p > 0.05) nor with the combination variable of all severe grade 3/4 events (p=0.08 for 50 gene panel).

Discussion

Recurrent ovarian malignancy is known to have a grave prognosis without available treatment regimens which significantly prolong survival. Therefore, the exceptional success of immunotherapy in other solid tumor types has led to considerable excitement about the possible impact of checkpoint inhibition for these patients and multiple trials are now ongoing. The data presented herein represents a single-institution experience with early phase trials involving immune checkpoint inhibition in recurrent ovarian cancer. While limited by sample size as well as significant heterogeneity, including different pathologic subtypes and highly varied treatment regimens, even among this mixed population certain interesting observations emerge.

There were 3 patients who had partial response and an additional 3 were noted to have pseudoprogression. This represents a response rate of approximately 15%, which is similar to previously reported in phase Ib-II trials in ovarian cancer [6]–[8]. Four of these patients were treated with checkpoint inhibitor as part of a combination regimen, or 66.7% of the responders, but this proportion mirrors that of the overall study cohort in that 63.6% of the total cohort received combination rather than monotherapy. The reported finding that high grade serous pathology predicts poorer survival (PFS and OS) may be a reflection of the aggressive nature of this disease when compared to other pathologic subtypes rather than a true relationship to survival after checkpoint inhibition.

The search for predictors of response, beyond intratumoral biomarkers such as PD-1/PD-L1, has thus far mostly focused on high mutational load and the presence of neoantigens. Identification of clinical predictors has proven to be more difficult. While some studies have reported a positive correlation between response and the presence of adverse event in other tumor types [3], [19]–[21], we were unable to identify any relationship between immune-related adverse event and response in this ovarian cancer cohort. In terms of prior therapy, in the subset analysis of only patients with high grade serous pathology, we demonstrated that platinum sensitivity at time of checkpoint inhibitor therapy predicted response. The possible relationship between platinum sensitivity and immune related response is novel and therefore has limited data available in the literature. Recent abstract data from a small platinum resistant ovarian cancer cohort of 18 patients demonstrated a reduction in chance of response with duration of platinum resistant disease [18]; while time since last platinum therapy was not statistically significant in the current cohort, these data also may suggest a relationship to platinum sensitivity.

Other types of prior therapy have been intermittently shown to have an impact, including decreased response to checkpoint with longer duration of prior anti-VEGF therapy inhibitors in metastatic renal cell carcinoma and a possible relationship between acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors and increased response to checkpoint therapy in non-small cell lung cancer [22], [23]. Therefore, though limited by sample size, this association between platinum sensitivity and improved response to checkpoint blockade is worthy of further study, as many of the trials of checkpoint inhibitor therapy have included only platinum-resistant disease [6], [8], [24]. While a relationship between platinum resistance and lower response to immunotherapy is intriguing, these data are based on small numbers and caution should be used in their interpretation until there is confirmation by other studies. Detailed characterization of mutations present and the tumor microenvironment prior to initiation of immune checkpoint inhibition, as well as changes which occur on treatment, will aid in explaining the intricate relationship present.

In terms of toxicity, the overall rate of severe adverse events with checkpoint inhibition in these early phase trials in ovarian cancer was similar to prior literature. However, the current study demonstrates higher rates of specifically severe hepatic and pancreatic enzyme elevations in this patient population. It could be hypothesized that these higher rates were related to the intraperitoneal spread and frequent liver metastasis that is present in ovarian cancer, however presence of hepatic tumor burden was not significantly associated with risk of experiencing a hepatic or pancreatic adverse event.

Prior literature in multiple tumor types demonstrates rates of hepatic toxicity range from 2–10% [25]–[28], but the rates of severe grade 3 or 4 events represent a smaller subset. A recent meta-analysis of randomized phase II/III trials from 1996–2006 across tumor types reported high grade AST elevations in only 94 of 3855 patients (1.5%) [29]. However, it is clear that the mechanism of checkpoint inhibition is closely related to the likelihood of these events. Grade 3 or 4 hepatic event rates with single agent anti-PD1 or PD-L1 are as low as 0–1%, while single agent anti-CTLA-4 rates are slightly higher at approximately 2%, and the combination ranges from 6% to as high as 15% in some individual studies [28], [30], [31]. In meta-analysis for hepatic adverse events, anti-PD1 have pooled odds ratios reported at 1.58 (95%CI 0.66–3.78) compared to pooled OR for anti-CTLA-4 of 4.67 (95%CI 3.42–6.39) respectively when compared to non-checkpoint therapy [32]. There is significantly less data regarding pancreatic enzyme elevations, as these are less frequent events with rates reported to be 1–2% in the subset of clinical trials where it was reported [19], [28], [32]–[34]. However, the relationship between higher rates with combination therapy and with specifically anti-CTLA-4 checkpoint inhibition seem to remain stable.

The higher rates found in this ovarian cancer patient population may represent a disease specific finding. Much like vitiligo is almost exclusively seen in melanoma patients and pneumonitis more common in lung cancer, it is possible that ovarian cancer lends an increased risk of hepatic or pancreatic enzyme elevations when treated with immune checkpoint. It is important to note that the higher rates presented are likely due to multifactorial risk; they may be in part due to treatment regimen, as the majority who had a severe hepatic or pancreatic event did receive combination therapy. However, only approximately 1/3 received a regimen which included anti-CTLA-4, which further suggests that the increased risk is not exclusively due to therapy choice.

Additionally, the number of genes mutated was found to be inversely correlated with likelihood of having one of these specific events; number of genes mutated was not correlated with any other type of adverse event or overall severe AE. It is possible that the reason gene mutation number was correlated only to hepatic and pancreatic events, rather than all AEs, is that other events are more likely to be misattributed to immune-related toxicity, such as a severe fatigue or hematologic event, while hepatitis or pancreatitis are more likely to be truly related to immune effect. It is worth emphasizing that the limited gene mutation data available within these trials cannot speak to true mutation load. The current trial does not present data regarding overall mutation burden, instead using the available proxy measurement of number of genes mutated in the panel testing performed. Interestingly, despite this fact, the data does suggest an association between number of genes mutated and these hepatic or pancreatic enzyme elevations. The etiology for such an association remains unknown. There is a wealth of data that indicates that mutation load is correlated to immunogenicity [35]–[38], therefore there is biologic plausibility that tumor immunogenicity may be related to particular subsets of immune-related adverse events. However, further research is needed to not only confirm this relationship but to better elucidate and explore the underlying mechanisms.

Conclusion

In this retrospective study of immune checkpoint inhibitor use among women with recurrent ovarian cancer, there is a response rate of 14.2%, similar to what has been previously reported. In patients with high grade serous pathology, platinum sensitivity at time of checkpoint inhibitor initiation was correlated to response. The data additionally demonstrated that there are higher proportions of severe pancreatic and hepatic enzyme elevation than has been described in other tumor types, which may help to inform investigators using immune checkpoint therapy in these patients. Interestingly, the number of genes mutated was inversely correlated to risk of hepatic or pancreatic AE but not to total AEs in this small cohort. Further more detailed study will be crucial to better establish not only which patient population will benefit from immunotherapy but also the patients most at risk for adverse event.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

−In early phase clinical trials for recurrent ovarian cancer, 14.2% of patients had partial response or pseudoprogression

−Severe (grade 3/4) hepatic and pancreatic enzyme elevations occurred in 13.6% of patients, or 27.2% total

−The number of mutations, as evaluated by panel genetic testing, was protective from hepatic/pancreatic severe adverse event

Acknowledgments

Statement of Funding:

This research was supported in part by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA016672), and a T32 training grant for gynecologic oncology (CA101642; to K.H. Lu). The funding sources had no input into the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations:

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interests to disclose related to the study and results reported.

References:

- [1].Naumann RW and Coleman RL, “Management strategies for recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian cancer,” Drugs, vol. 71, no. 11 pp. 1397–1412, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zhang L et al. , “Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer.,” N. Engl. J. Med, vol. 348, no. 3, pp. 203–13, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hamanishi J et al. , “Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes are prognostic factors of human ovarian cancer.,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, vol. 104, no. 9, pp. 3360–5, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Robert C et al. , “Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma,” N. Engl. J. Med, vol. 372, no. 26, pp. 2521–2532, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Garon EB et al. , “Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer,” N. Engl. J. Med, vol. 372, no. 21, pp. 2018–2028, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Disis ML et al. , “Avelumab (MSB0010718C; anti-PD-L1) in patients with recurrent/refractory ovarian cancer from the JAVELIN Solid Tumor phase Ib trial: Safety and clinical activity.,” J. Clin. Oncol, vol. 34, no. 15_suppl, p. 5533, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Varga A et al. , “Antitumor activity and safety of pembrolizumab in patients (pts) with PD-L1 positive advanced ovarian cancer: Interim results from a phase Ib study,” J. Clin. Oncol, vol. 33, no. 15_suppl, p. 5510, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hamanishi J et al. , “Safety and antitumor activity of Anti-PD-1 antibody, nivolumab, in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer,” J. Clin. Oncol, vol. 33, no. 34, pp. 4015– 4022, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pakish JB and Jazaeri AA, “Immunotherapy in Gynecologic Cancers: Are We There Yet?,” Current Treatment Options in Oncology, vol. 18, no. 10 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ring KL, Pakish J, and Jazaeri AA, “Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in the Treatment of Gynecologic Malignancies.,” Cancer J, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 101–7, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sharma P and Allison JP, “The future of immune checkpoint therapy,” Science (80-. ), vol. 348, no. 6230, pp. 56–61, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wenham RM DD, Apte SM, Shahzad MM, Lee JK, “Phase II trial of dose dense (weekly) paclitaxel with pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer,” J. Clin. Oncol, p. TPS 5612, 2016.

- [13].Pujade-Lauraine E LJ, Colombo N, Disis ML, Fujiwara K, “Avelumab (MSB0010718C; anti-PD-L1) +/− pegylated liposomal doxorubicin vs pegylated liposomal doxorubicin alone in patients with platinum-resistant/refractory ovarian cancer: the phase III JAVELIN Ovarian 200 trial,” J. Clin. Oncol, p. TPS5600, 2016.

- [14].Padhani AR and Ollivier L, “The RECIST criteria: Implications for diagnostic radiologists,” British Journal of Radiology, vol. 74, no. 887 pp. 983–986, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Eisenhauer EA et al. , “New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1),” Eur. J. Cancer, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 228–247, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wolchok JD et al. , “Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: Immune-related response criteria,” Clin. Cancer Res, vol. 15, no. 23, pp. 7412– 7420, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cancer T Genome Atlas Research Network et al. , “Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma,” Nature, vol. 474, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Oldenburg J, Normann M, Turzer M, Solheim O, Diep LM, Gajdzik B. “PD-1 inhibitor treatment of platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer,” J. Clin. Oncol, vol. 36, no. 15_suppl, p. 17555, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Freeman-Keller M, Kim Y, Cronin H, Richards A, Gibney G, and Weber JS,”Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: Characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes,” Clin. Cancer Res, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 886–894, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hua C et al. , “Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab,” JAMA Dermatology, vol. 152, no. 1, pp. 45–51, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Horvat TZ et al. , “Immune-related adverse events, need for systemic immunosuppression, and effects on survival and time to treatment failure in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab at memorial sloan kettering cancer center,” J. Clin. Oncol, vol. 33, no. 28, pp. 3193–3198, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Han JJ et al. , “Change in PD-L1 expression after acquiring resistance to gefitinib in EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer,” Clin. Lung Cancer, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 263– 270, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jeyakumar G et al. , “Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and duration of prior anti-angiogenic therapy as biomarkers in metastatic RCC receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,”J. Immunother. Cancer, vol. 5, no. 1, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Varga A et al. , “Antitumor activity and safety of pembrolizumab in patients (pts) with PD-L1 positive advanced ovarian cancer: Interim results from a phase Ib study,” J. Clin. Oncol, vol. 33, no. 15_suppl, p. 5510, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Nanda R et al. , “Pembrolizumab in Patients With Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 Study.,” J. Clin. Oncol, pp. 1–10, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [26].et al LY., “Atezolizumab (atezo) in platinum (plat)-treated locally advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC): Updated OS, safety and biomarkers from the Ph II IMvigor210 study,” Ann. Oncol, vol. 27, pp. 1–20, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hodi FS et al. , “Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in patients with advanced melanoma: 2-year overall survival outcomes in a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial,” Lancet Oncol, vol. 17, no. 11, pp. 1558–1568, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wolchok JD et al. , “Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma,” N. Engl. J. Med, p. NEJMoa1709684, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [29].et al. Velaso G; Je Y; Bosse D; Awad M; Ott P; Moreira R, “Comprehensive meta-analysis of key immune-related adverse events from CTLA-4 and PD-1 / PD-L1 inhibitors in cancer patients.,” Cancer Immunol. Res, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 312–318, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Baxi S et al. , “Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: Systematic review and meta-analysis,” BMJ (Online), vol. 360 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Brahmer JR et al. , “Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline,” J. Clin. Oncol, vol. 4, p. JCO.2017.77.638, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wang W, Lie P, Guo M, and He J, “Risk of hepatotoxicity in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published data,” Int. J. Cancer, vol. 141, no. 5, pp. 1018–1028, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Brahmer JR et al. , “Safety and Activity of Anti–PD-L1 Antibody in Patients with Advanced Cancer,” N. Engl. J. Med, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [34].Suzman DL, Pelosof L, Rosenberg A, and Avigan MI, “Hepatotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: An evolving picture of risk associated with a vital class of immunotherapy agents,” Liver Int, no. March, pp. 976–987, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Llosa NJ et al. , “The vigorous immune microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer is balanced by multiple counter-inhibitory checkpoints,” Cancer Discov, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 43–51, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Pakish JB et al. , “Immune microenvironment in microsatellite-instable endometrial cancers: Hereditary or sporadic origin matters,” Clin. Cancer Res, vol. 23, no. 15, pp. 4473–4481, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tougeron D et al. , “Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability are correlated with the number and spectrum of frameshift mutations,” Mod. Pathol, vol. 22, no. 9, pp. 1186–1195, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Howitt BE et al. , “Association of polymerase e-mutated and microsatellite-instable endometrial cancers with neoantigen load, number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, and expression of PD-1 and PD-L1,” JAMA Oncol, vol. 1, no. 9, pp. 1319–1323, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.