Abstract

Mutations in the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) gene account for most common causes of familial and sporadic Parkinson’s disease (PD) and are one of the strongest genetic risk factors in sporadic PD. Pathways implicated in LRRK2-dependent neurodegeneration include cytoskeletal dynamics, vesicular trafficking, autophagy, mitochondria, and calcium homeostasis. However, the exact molecular mechanisms still need to be elucidated. Both genetic and environmental causes of PD have highlighted the importance of mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of PD. Mitochondrial impairment has been observed in fibroblasts and iPSC-derived neural cells from PD patients with LRRK2 mutations, and LRRK2 has been shown to localize to mitochondria and to regulate its function. In this review we discuss recent discoveries relating to LRRK2 mutations and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, LRRK2, mitochondrial dysfunction, mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy, trafficking

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common motor neurodegenerative disorder affecting approximately 1% of the population above 60 years of age. It is characterized by the selective loss of dopaminergic neurons in substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) innervating the basal ganglia (Lees et al., 2009). Hallmark symptoms of PD include rigidity, bradykinesia, and test tremor. More than 90% of the cases are sporadic; however, 10% of the cases are caused by monogenic mutations and 23 causative genes have so far been identified, including ±-synuclein, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1), Parkin, DJ-1, etc (Kalia and Lang, 2015). Neurodegeneration in PD is typically accompanied by the presence of protein inclusions termed Lewy bodies in surviving neurons that are enriched with α-synuclein protein. However, the exact etiology and precise cause of PD has yet to be fully characterized, but involves dysfunction of numerous processes, including mitochondrial function, calcium homeostasis, dopamine (DA) homeostasis, autophagy, and proteostasis (Kalia and Lang, 2015).

Mitochondrial dysfunction has emerged as one of the key mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of both sporadic PD and familial Parkinsonism (For more details on PD and mitochondrial dysfunction see the reviews by Giannoccaro 2017 and Larsen 2018 (Giannoccaro et al., 2017; Larsen et al., 2018). Specifically, the mitochondrial complex I activity is decreased by 40% in the substantia nigra region of the midbrain in PD patients, and complex I subunits are selectively reduced (Bindoff et al., 1989; Hattori et al., 1991; Schapira et al., 1990). Interestingly, complex I inhibitors such as 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and rotenone induce a clinical syndrome mimicking PD phenotypes in both human and non-human primates (Beal, 2003; Dauer and Przedborski, 2003). Further evidences for the involvement of mitochondrial dysfunction in PD pathogenesis comes from the fact that several disease-related genes such as PINK1, Parkin, DJ1 are linked to mitochondrial pathways (Bose and Beal, 2016). Vulnerability of SNc DA neurons in PD is in part due to their particular bioenergetics and morphological characteristics. SNc DA neurons have a higher energy demand for normal function than those that are less vulnerable due to their long and highly-branched, unmyelinated axonal arbors (Pissadaki and Bolam, 2013). SNc DA neurons have a higher basal rate of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) which may confer a further increase in risk (Pacelli et al., 2015).

Mutations in the LRRK2 gene (PARK8) are the most prevalent causes of the late-onset autosomal dominant type of PD (Paisan-Ruiz et al., 2004; Zimprich et al., 2004), accounting for 5-6% of familial and 1-2% of sporadic PD cases (Bardien et al., 2011; Farrer et al., 2005; Gilks et al., 2005; Hardy, 2010). Six LRRK2 mutations have a proven pathogenicity (Ross et al., 2011): R1441C/G, N1437H, Y1699C, G2019S and I2020T. Recently, it is shown that LRRK2 contributes to the risk of sporadic PD (Nalls et al., 2014). Importantly, in most LRRK2 mutation carriers, the clinical and pathological features are indistinguishable from those of sporadic PD, demonstrating an unprecedentedly significant role of LRRK2 in PD pathogenesis (Gosal et al., 2005).

LRRK2 is a multifunctional complex protein, 2527-amino-acids long with multiple domains, including a leucine-rich repeat (LRR), a ROC-COR GTPase, a mitogen-activated protein kinase, and WD40 domains. Not surprisingly, it participates in a broad range of cellular activities, and extensive studies suggest that LRRK2 pathogenesis involves diverse signaling pathways and cellular processes such as cytoskeleton remodeling, vesicular trafficking, autophagy, mitochondria dynamics and quality control, protein translation (Cookson, 2010; Price et al., 2018; Roosen and Cookson, 2016; Taymans et al., 2015). The most frequent mutation, G2019S, found in the kinase domain, shows increased LRRK2 kinase activity (West et al., 2005).

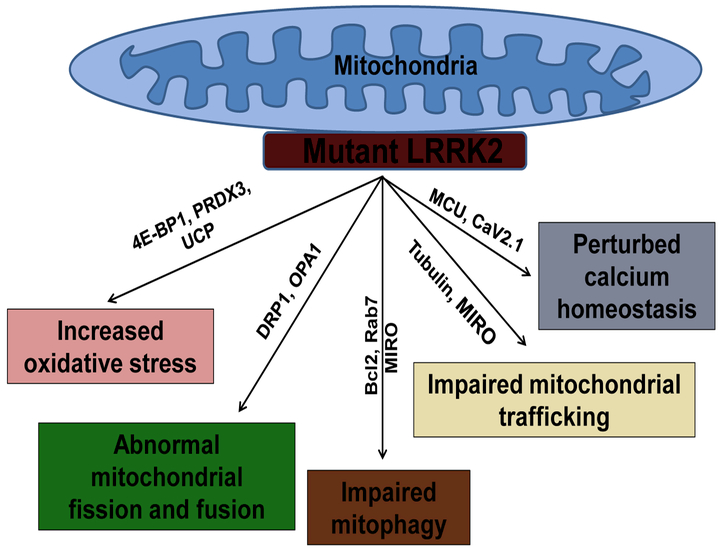

LRRK2 interacts with a number of key regulators of mitochondrial fission/fusion, co-localizing with them either in the cytosol or on mitochondrial membranes, indicating that it has multiple regulatory roles (Stafa et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2012). Thus, LRRK2 might directly affect mitochondrial function in addition to indirectly regulating it through autophagy or cytoskeletal dynamics. This hypothesis is of great interest as mitochondrial dysfunction is central to PD pathogenesis (Beal, 2005; Bose and Beal, 2016). A growing body of evidence supports a role for LRRK2 in mitochondrial function. Mitochondrial dysfunctions (higher oxidative stress, reduced mitochondria membrane potential and decreased ATP production, mitochondria DNA damage, elongated mitochondria, mitochondrial fragmentation, mitophagy) were observed in postmortem human tissues from LRRK2-linked PD patients, various animal models of G2019S-LRRK2 PD (Table 1) (Cooper et al., 2012; Mortiboys et al., 2010; Sanders et al., 2014; Yue et al., 2015) and cellular models of the disease (Cherra et al., 2013; Niu et al., 2012; Su and Qi, 2013; Wang et al., 2012). Exactly how LRRK2 mutations could lead to mitochondrial dysfunction is not yet clear, but recent advances have provided a number of clues (Fig. 1). In this review, we discuss our understanding of how LRRK2 mutations perturb mitochondrial function, ultimately contributing to PD pathogenesis.

Table 1.

LRRK2 mutations and mitochondrial dysfunction

| Model | LRRK2 variants |

Mitochondrial oxidative stress |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast | G2019S R1441C |

Increased ROS | Pereira et al., 2014 |

| C. elegans | KO | Reduced oxidative stress in PINK1 loss of function allele background | Samann et al., 2009 |

| C. elegans | G2019S | Increased vulnerability of DA neurons to ROT | Saha et al., 2009 |

| Drosophila | G2019S | Increased sensitivity to ROT, rescued by Parkin | Ng et al., 2009 |

| Drosophila | G2019S | Increased oxidative stress | Angeles et al., 2014 |

| Drosophila | dLrrk | Regulates response to oxidative stress via 4E-BP phosphorylation | Imai et al., 2008; Tain et al., 2009 |

| NLCs from PD patients | G2019S | Increased sensitivity to ROT rescued by LRRK2 inhibitors | Mendivil-Perez et al., 2016 |

| NSCs from mice | R1441G | Higher oxidative stress | Bahnassawy et al., 2013 |

| Rat midbrain neurons PD patients fibroblasts | G2019S | Increased mtDNA damage rescued by LRRK2 inhibitor | Howlett et al., 2017 |

| PD patients fibroblasts | G2019S | UCP2 increased ROS increased | Grunewald et al. 2014 |

| PD patients fibroblasts | G2019S | UCP4 mRNA up-regulated | Papkovskaia et al., 2016 |

| PD patients fibroblasts | G2019S R1441C |

Increased vulnerability to valinomycin | Smith et al., 2016 |

| iPSCs-derived DA neurons from PD patients | G2019S | Increased sensitivity tooxidative stress | Nguyen et al., 2011 |

| iPSCs-derived neurons from PD patients | G2019S | Increased sensitivity to ROT attenuated by LRRK2 inhibitor | Reinhardt et al., 2013 |

| iPSCs-derived neurons from PD patients | G2019S | Increased oxidative damage | Sanders et al., 2014 |

| iPSCs-derived neurons from PD patients | G2019S R1441C |

Oxygen consumption decreased | Cooper et al., 2012 |

| Model |

LRRK2 Variants |

Mitochondrial fission and fusion | References |

| Mouse cortical neuron cultures | G2019S | Increased fission | Niu et al., 2012 |

| SH-SY5Y cells Rat cortical neuron cultures | G2019S R1441C |

Increased mitochondrial fragmentation | Wang et al., 2012 |

| Mouse brains | G2019S knock-in |

Mitochondrial fission arrested | Yue et al., 2015 |

| PD patients fibroblasts | G2019S | Elongated, interconnected mitochondria, reduced MMP and ATP production | Mortiboys et al., 2010 |

| Hela cells PD patients fibroblasts | G2019S | Excessive mitochondrial fission which could be blocked by Drp1 inhibitor | Su and Qi, 2013 |

| PD patients fibroblasts | G2019S R1441C |

Increased mitochondrial fragmentation | Grunewald et al., 2014,Smith et al., 2016 |

| PD patients fibroblasts | E193K | Abnormal mitochondrial fission | Carrion et al., 2018 |

| PD patient brains | G2019S | Decreased OPA1 | Stafa et al., 2014 |

| Model |

LRRK2 Variants |

Mitophagy | References |

| SH-SY5Y cells | LRRK2 inhibitor | Promotes mitophagy | Saez-Atienzar et al., 2014 |

| Mouse cortical neuron cultures | G2019S R1441C |

Increased Mitophagy | Cherra et al., 2013 |

| Mouse brains | G2019S | Increased number of autophagic vacuoles and damaged mitochondria | Ramonet et al., 2011 |

| PD patients fibroblasts Rat DA neuron culture | G2019S | Excessive mitophagy | Su et al., 2015 |

| PD patients fibroblasts | G2019S R1441C |

Heightened mitophagy | Smith et al., 2016 |

| iPSC-derived neurons from PD patients | G2019S | Delayed mitophagy | Hsieh et al., 2016 |

| Model |

LRRK2 Variants |

Cytoskeleton dynamics and mitochondria trafficking | References |

| Cultured neurons from mice | G2019S | Decreased free tubulin | Parisiadou et al., 2009 |

| Mice | LRRK2 KO | Increased free tubulin | Gillardon et al., 2009 |

| HEK293T cells | R1441C,R1441G, Y1699C, I2020T |

Increased association with microtubules | Kett et al., 2012 |

| HEK293T cells | R1441G KO |

Altered tubulin acetylation | Law et al., 2014 |

| PBMC from PD patients | G2019S Sporadic PD |

Decreased tubulin acetylation | Esteves et al., 2015 |

| Mice | G2019S | Impaired microtubule assembly | Lin et al., 2009 |

| Mouse Synaptoneurosome PD patient fibroblasts | R1441G G2019S |

Destabilize F-actin | Caesar et al., 2015 |

| Drosophila | G2019S | Increased tau phosphorylation | Lin et al., 2010 |

| Mice | G2019S | Increased tau phosphorylation | Melrose et al., 2010 |

| SH-SY5Y cells | R1441C | Hampered mitochondria transport | Thomas et al., 2016 |

| Rat cortical neurons Drosophila | R1441C | Decreased mitochondria transport | Godena et al., 2014 |

| iPSC-derived neurons from PD patients | G2019S | Decreased mitochondria transport | Hsieh et al., 2016 |

| iPSC-derived DA neurons from PD patients | G2019S | Increased mitochondria mobility | Schwab et al., 2017 |

Abbreviations: HEK-293T: human embryonic kidney 293 cells; iPSC: induced pleuripotent stem cell; NLC: nerve like differentiated cells; NSC: neural stem cell; PMBC: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells; ROT: rotenone; Drp1: dynamin related protein; OPA1: optic atrophy 1; UCP2: uncoupling protein 2; MMP: mitochondrial membrane potential; PINK-1: PTEN-induced kinase

Fig 1: Diagram showing pathways and molecules affecting mitochondrial function.

Abbreviations: Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma 2; DRP1: dynamin like protein; 4E-BP1: eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1; MCU: mitochondrial calcium uniporter; OPA1: optic atrophy 1: PRDX3: peroxiredoxin 3

2. Subcellular localization of LRRK2

LRRK2 normally exists as a dimeric structure minimally mediated via its ROC domain, and dimerization is required for its kinase activity and localization to cellular membranes (Berger et al., 2010; Deng et al., 2008; Greggio et al., 2008; Sen et al., 2009). The WD40 domain also appears to be important for dimerization and kinase activity (Jorgensen et al., 2009). Although the majority of LRRK2 protein is present in the cytoplasm, about 10% of LRRK2 is present in the mitochondrial fraction of cells over-expressing the protein and is associated with the mitochondrial outer membrane in rodent brains (Biskup et al., 2006; West et al., 2005). In rat primary cortical neuronal cultures, confocal images showed a partial overlap of LRRK2 immunoreactivity with mitochondrial and lysosomal markers (Biskup et al., 2006). Ultrastructural analysis revealed that LRRK2 is associated with intracellular membranes, including lysosomes, transport vesicles, and mitochondria in rodent brains. Thus, the specific association of a fraction of LRRK2 with mitochondria and its ability to induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis (Cui et al., 2011; Iaccarino et al., 2007), raise the possibility that LRRK2 may compromise mitochondrial function when over-expressed or mutated leading to PD pathogenesis (Biskup et al., 2006).

3. LRRK2 and mitochondrial oxidative stress

Oxidative stress is the result of disequilibrium between excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and limited antioxidant defenses. ROS can lead to oxidative damage of proteins, DNA, and lipids (Raha and Robinson, 2000). Mitochondria generate most of the ROS as a byproduct of OXPHOS by the respiratory chain complex. Superoxide anion, which is produced mainly by mitochondrial complexes I and III of the electron transport chain, is highly reactive and can easily cross the inner mitochondrial membrane, where it can be reduced to H2O2. Familial PD cases have unequivocally been found to be related to mitochondrial complex I dysfunction (Betarbet et al., 2000; Dauer and Przedborski, 2003; Ved et al., 2005). The PD-susceptible SNc DA neurons in mouse primary culture showed elevated OXPHOS and increased ROS production (Pacelli et al., 2015). One of the probable reasons could be the large axonal arborization of the SNc DA neurons. SNc DA neurons display an increased density of mitochondria and an elevated ATP production, which are factors contributing to ROS (Pacelli et al., 2015).

Multiple studies have demonstrated that LRRK2 mutant is associated with an increased susceptibility to oxidative stress, leading to increased cell death (Cooper et al., 2012; Imai et al., 2008; Mendivil-Perez et al., 2016; Ng et al., 2009; Nguyen et al., 2011; Pereira et al., 2014; Reinhardt et al., 2013). Rotenone is a specific inhibitor that binds to the ubiquinone binding site of mitochondria complex I, thus preventing electron transfer via flavin mononucleotide (FMN) to coenzyme Q10. Consequently, interruption of the OXPHOS chain concomitantly generates ROS such as superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. LRRK2 G2019S-expressing flies display reduced lifespan and increased sensitivity to rotenone (Ng et al., 2009). Rotenone induces DNA fragmentation, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, and intracellular ROS generation in nerve-like differentiated cells carrying the G2019S mutation, and this could be reversed by LRRK2 kinase inhibitor (Mendivil-Perez et al., 2016). Moreover, multiple groups have demonstrated increased susceptibility to oxidative stress in LRRK2 mutant iPSC-derived DA neurons (Nguyen et al., 2011) and neurons (Cooper et al., 2012).

The intrinsic cellular redox state is also influenced by LRRK2 mutations in some model systems. Neural stem cells carrying the R1441G mutation displayed higher oxidative stress, increased rates of cell death, and impaired neuronal differentiation (Bahnassawy et al., 2013). The basal oxygen consumption rate (OCR) is reduced in iPSC-derived neural cells from PD patients carrying the homozygous G2019S mutation and the heterozygous R1441C mutation in LRRK2 when compared to healthy controls (Cooper et al., 2012). Notably, these mitochondria defects can be rescued by a LRRK2 inhibitor (Cooper et al., 2012). Finally, enhanced mitochondrial DNA damage is found in iPSC-derived neural cells from patients carrying the G2019S mutation (Howlett et al., 2017; Sanders et al., 2014). DNA damage could both cause and result from oxidative stress.

On the other hand, pathogenic LRRK2 mutations can decrease the antioxidant defenses of mitochondria through several different mechanisms. It is reported that LRRK2 kinase mutant G2019S significantly increased phosphorylation of peroxiredoxin 3 (PRDX3), the most important scavenger of hydrogen peroxide in the mitochondria, compared to the wild-type. The increase in PRDX3 phosphorylation was associated with decreased peroxidase activity in the Drosophila brain (Angeles et al., 2014). Both motor dysfunction and mitochondrial degeneration present in LRRK2 mutants were ameliorated by PRDX3 (Angeles et al., 2014). Another possibility for mutant LRRK2 to decrease the antioxidant defenses of mitochondria came from hyper-phosphorylation of 4E-BP. 4E-BP1 is an inhibitor of translation that has been implicated in mediating the survival response to oxidative stress. Hyper-phosphorylation of 4E-BP in vivo can lead to reduced oxidative stress resistance and dopaminergic neurodegeneration (Imai et al., 2008; Tain et al., 2009). Finally, LRRK2 mutant may affect neuronal uncoupling proteins (UCPs) which are crucial for reducing the production of ROS and consequent oxidative stress (Conti et al., 2005). Expression of UCP2, which has been identified as the cause of mitochondrial proton leakage in fibroblasts from LRRK2 PD patients with the G2019S muation (Papkovskaia et al., 2012), is upregulated in response to elevated ROS generation in affected mutation carriers. Restoration of mitochondrial membrane potential by the UCP inhibitor genipin confirmed the role of UCPs in this mechanism (Grunewald et al., 2014; Papkovskaia et al., 2012).

Interestingly, studies in C. elegans (Saha et al., 2009; Samann et al., 2009) and Drosophila (Venderova et al., 2009) suggest an antagonistic effect of the LRRK2 and PINK1 genes (Samann et al., 2009). PINK1 exerts directly or indirectly an inhibitory effect on LRRK2 in fibroblasts or iPSC-derived DA neurons from PD patients with PINK1 mutations (Azkona et al., 2016). Ectopic expression of human Parkin in LRRK2 G2019S-expressing flies provides significant protection against DAergic neurodegeneration that occurs with age or in response to rotenone (Venderova et al., 2009). Notably, Parkin appears to interact with LRRK2 physically in vitro (Smith et al., 2005).

4. LRRK2 and mitochondrial dynamics and quality control

4.1. LRRK2 and mitochondrial fission and fusion

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that constantly fuse and divide. These processes, collectively termed mitochondrial dynamics, are important for mitochondrial inheritance and for the maintenance of mitochondrial functions. The dynamic balance of fission and fusion contributes to mitochondrial health. These processes help transmitting energy across long distances within the cell, which are required for axonal and synaptic functions (Baloh et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2007; Hoppins et al., 2007). Any perturbation from these dynamic processes would lead to disease phenotypes. The process of fission and fusion is regulated by molecular machinery that includes dynamin-related GTPases and WD40 repeat-containing proteins. Since the LRRK2 protein contains both GTPase and WD40 domains, it could potentially serve as a scaffold during mitochondrial fission and fusion events.

LRRK2 mutations associated with PD have been shown to alter mitochondrial fusion/fission but with conflicting results. Fibroblasts derived from human PD patients with the G2019S mutation have elongated mitochondria (Mortiboys et al., 2010). Homo LRRK2 G2019S knock-in mice display progressive changes in mitochondria that are consistent with arrested fission (Yue et al., 2015). Conversely, most studies show that LRRK2 mutants cause fragmentation of mitochondria (Grunewald et al., 2014; Niu et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2016; Su and Qi, 2013; Wang et al., 2012). Interconnectivity of mitochondria is reduced in fibroblast culture from PD patients carrying the G2019S mutation as compared to control subjects (Grunewald et al., 2014). Smith and colleagues reported that PD-derived fibroblasts displayed a fragmented mitochondrial network which could be attenuated by a LRRK2 inhibitor (Smith et al., 2016). Over-expression of LRRK2 G2019S mutant can induce mitochondrial fragmentation in primary cortical neurons through interacting with dynamin-like protein 1 (DLP1, a mitochondrial fission protein) (Niu et al., 2012). Along the same line, human dopaminergic neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y expressing LRRK2 mutants (G2019S and R1441C) exhibits severe mitochondrial fragmentation with shorter and smaller mitochondria observed in electron micrographs (Wang et al., 2012). The mechanistic investigation revealed that LRRK2 regulates mitochondrial dynamics through direct interaction with DLP1. Similar results were observed by Su and Ki in PD patient fibroblasts, wherein mitochondrial fission was accelerated by LRRK2 G2019S mutant by recruiting the dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) to the mitochondria (Su and Qi, 2013). Notably, the kinase activity of LRRK2 is required for its interaction with DRP1 and mitochondrial fragmentation in these studies (Smith et al., 2016; Su and Qi, 2013; Wang et al., 2012). In a recent investigation, a novel LRRK2 variant E193K identified in an Italian family, was found to alter LRRK2 binding to DRP1 thus affecting fission (Perez Carrion et al., 2018). Further, optic atrophy 1 (OPA1, a protein controlling mitochondria fusion) levels were reported to be reduced in G2019S PD patient brains (Stafa et al., 2014).

Another recent and very intriguing finding has implicated the role of lysosomal RAB7 in mitochondrial fission (Wong et al., 2018). The study demonstrated the existence of Mitochondria-lysosome contacts and the contacts can regulate mitochondrial fission via RAB7 GTP hydrolysis (Wong et al., 2018). Since RAB7 is one of the substrates of LRRK2 (Beilina et al., 2014), it is plausible that LRRK2 mutants affect mitochondrial dynamics in PD via regulating RAB GTP hydrolysis.

4.3. LRRK2 and mitophagy

Autophagy is a key cellular catabolic process wherein the cytosolic components, including mainly dysfunctional organelles, misfolded proteins, and surplus or unnecessary cytoplasmic contents are transported to lysosomes for digestion. Mitophagy describes the clearance of damaged mitochondria. Dysregulation of mitophagy plays important roles in neurodegenerative diseases (Vives-Bauza and Przedborski, 2011). There is substantial evidence suggesting that LRRK2 regulates autophagy (Beilina et al., 2014; Cherra et al., 2013; Cookson, 2016; Ferree et al., 2012; Hindle et al., 2013; Hsieh et al., 2016; Orenstein et al., 2013; Ramonet et al., 2011; Saha et al., 2015; Schapansky et al., 2014; Tong et al., 2012).

LRRK2 mutants have been shown to activate dendritic mitochondrial clearance by autophagy in cortical neuronal culture (Cherra et al., 2013). Inhibition of LRRK2 impairs autophagy by altering autophagosome-lysosome fusion, causes DRP1-mediated mitochondrial fission, and induces mitophagy in SH-SY5Y (Saez-Atienzar et al., 2014). Interestingly, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential has been observed in fibroblasts from PD patients harboring the G2019S LRRK2 mutation (Su et al., 2015). This was accompanied by an increase in autophagic flux and higher expression of autophagy markers in LRRK2 mutants. In HeLa cells, expressing wild-type and mutant LRRK2 G2019S induced mitochondrial mass loss. Further investigation revealed that G2019S bound to and phosphorylated Bcl2, resulting in excessive mitophagy (Su et al., 2015). LRRK2 PD-patient-derived fibroblast lines displayed a more fragmented mitochondrial network and heightened mitophagy at baseline (Smith et al., 2016).

While the above evidence suggests that LRRK2 affects mitophagy via autophagy indirectly, studies from Xinnnan Wang’s group have demonstrated a direct role of LRRK2 in mitophagy (Hsieh et al., 2016). Miro is an outer mitochondrial membrane protein that anchors the microtubule motors kinesin and dynein to mitochondria. They reported that LRRK2 in iPSC-derived neurons causes the removal of damaged mitochondria by forming a complex with Miro, thereby promoting its displacement from damaged mitochondria (Hsieh et al., 2016). Mutant LRRK2 (G2019S) disrupts this complex, slows Miro removal and delays the subsequent mitophagy.

4.3. LRRK2 and mitochondrial trafficking

Axonal transport is critical for maintaining healthy neurons as neurons are highly polarized cells that utilize specific motor proteins to travel along cytoskeletons composed of microtubules. Defects in axonal transport can lead to disruption in energy homeostasis, impaired protein clearance pathways, neurite shortening, and eventual cell death (Fu and Holzbaur, 2014; Maday et al., 2014).

LRRK2 has been shown to interact with microtubules and cytoskeleton proteins (Beilina et al., 2014; Caesar et al., 2013; Law et al., 2014). Co-localization and ultrastructural analyses in primary neuronal cultures showed that LRRK2 interacts closely with microtubules in a well-ordered, periodic fashion, suggesting the existence of a LRRK2-binding site on microtubules or microtubule-bound proteins (Kett et al., 2012). Interestingly, it was found that the level of free tubulin is significantly increased in the brain extracts of LRRK2 knock-out mice (Gillardon, 2009), whereas it is dramatically decreased in the brain homogenates of LRRK2 wild-type and G2019S transgenic mice (Parisiadou et al., 2009). Thus LRRK2 might be a potential stabilizing protein for microtubule assembly. LRRK2 has been shown to physically interact with tubulin proteins via its GTPase domain; it phosphorylates them, thereby increasing tubulin polymerization in vitro (Gandhi et al., 2008; Gillardon, 2009). Consistent with this observation, microtubule assembly is impaired in mice overexpressing the wild-type or G2019S mutant LRRK2 (Lin et al., 2009). Another study suggests that G2019S LRRK2 expression may cause dendrite degeneration in Drosophila by promoting the phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau via GSK3β homolog Shaggy (Lin et al., 2010).

Tubulin acetylation is a post-translational modification associated with microtubules stability and has a prevalent role in axonal microtubule structure and function (Esteves et al., 2014; Esteves et al., 2015; Godena et al., 2014). Acetylation of microtubules promotes microtubule-dependent trafficking (Reed et al., 2006). In isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from both sporadic PD and LRRK2 G2019 patients, it has been observed that tubulin acetylation is decreased when compared to age-matched healthy individuals (Esteves et al., 2015). Perturbed microtubule assembly has also been observed in vivo in postmortem brain tissue of LRRK2-associated PD patients, and in transgenic and viral-based rodent models expressing LRRK2 mutants (Dusonchet et al., 2011; Li et al., 2009; MacLeod et al., 2006; Melrose et al., 2010; Rajput et al., 2006; Zimprich et al., 2004). LRRK2, thus, seems to have a role in maintaining microtubule dynamics. Disturbances in the microtubule network would affect axonal transport including mitochondria trafficking. LRRK2 R1441C (Roc-COR) mutant inhibits axonal mitochondria transport as well as locomotion in Drosophila (Godena et al., 2014). The mutant LRRK2 R1441C and Y1699C inhibits microtubule acetylation, hampering axonal transport. Inhibiting histone deacetylases restores axonal transport and locomotion (Godena et al., 2014). Also, cells expressing the R1441C mutant display hampered mitochondrial transport, decreased number of mitochondria traveling in both anterograde and retrograde direction, and significantly decreased the total run length of mitochondria as compared to control. These aberrations could be attenuated by treatment with LRRK2-specific GTP-binding inhibitors (Thomas et al., 2016).

While the above evidence suggests that LRRK2 affects mitochondria trafficking indirectly by modulating microtubule stability, Wang and her colleagues demonstrate a direct role of LRRK2 in mitochondria trafficking in iPSC-derived neurons by interaction with Miro. LRRK2 removes damaged mitochondria by forming a complex with Miro, thereby promoting its displacement from damaged mitochondria (Hsieh et al., 2016). G2019S LRRK2 mutant disrupts this complex therefore, Miro remains on damaged mitochondria which keep trafficking. In summary, the experiments conducted so far show that axonal transport of mitochondria is affected by LRRK2 mutations, which might play an important role in PD pathogenesis. Notably, the defects could not be rescued by LRRK2 kinase inhibitors (Hsieh et al., 2016; Schwab et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2016).

LRRK2 can also disturb mitochondrial homeostasis by affecting the PGC-1α pathway. Genetic or pharmacological activation of the Drosophila PGC-1α ortholog pargel is sufficient to rescue the disease phenotypes of LRRK2 genetic fly models of PD (Ng et al., 2017).

5. LRRK2 and calcium homeostasis

Mitochondria are involved in maintaining calcium homeostasis such as sequestering Ca2+ in neurons through the low affinity mitochondrial uniporter and its associated regulators (Patron et al., 2013). Perturbed calcium homeostasis has been suggested for the pathogenesis of PD. The PD-susceptible SNc DA neurons rely upon voltage-gated calcium channels for autonomous pacemaking, thus putting an excess metabolic burden in terms of ATP to expel the excess calcium in every round of depolarization (Surmeier et al., 2011). Some evidence suggests that constant and long-lasting elevations of cytosolic Ca2+ occurring in SNc DA neurons are directly leading to increased ROS production from mitochondria, thereby augmenting cell death sensitivity (Egnatchik et al., 2014; Guzman et al., 2010; Lemasters et al., 2009; Singh et al., 2018). During aging and in neurodegenerative disease processes, the ability of neurons to maintain an adequate energy level is compromised, thus impacting on Ca2+ homeostasis (Cali et al., 2014; Raffaello et al., 2016).

Studies analyzing the direct involvement of LRRK2 in calcium homeostasis are scarce. Cortical neurons expressing mutant LRRK2 have shown defects in Ca2+ buffering capacity, which results in impairments of mitochondrial function, degradation, and dendritic shortening. Accordingly, the inhibition of the L-type of Ca2+ channels or treatments with Ca2+ chelators revert the phenotype (Cherra et al., 2013). LRRK2 G2019S iPSC-derived sensory neurons display diminished calcium responses to KCl depolarization. These phenotypes could be partially rescued by treatment with LRRK2 kinase inhibitors (Schwab and Ebert, 2015).

Perturbed calcium homeostasis has been shown to play a role in LRRK2-induced autophagy. Overexpression of wild-type or G2019S LRRK2 in HEK-293 cells has been reported to activate the nicotinic acid/adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) receptors to cause Ca2+ efflux from lysosomes (Gomez-Suaga et al., 2012), which results in the induction of autophagy. Consequently, enhanced cytosolic Ca2+ could have downstream effects on other Ca2+-dependent cellular events.

Mitochondria are involved in maintaining calcium homeostasis such as sequestering Ca2+ in neurons through the low affinity mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) and its associated regulators (Patron et al., 2013). There is some evidence to show PINK1 can influence the activity of mitochondrial Ca2+ transport systems (Marongiu et al., 2009), and inhibition of the MCU rescues dopaminergic neurons in PINK1-deficient Zebrafish (Soman et al., 2017). A recent study shows that pathogenic LRRK2 mutants cause increased dendritic and mitochondrial calcium uptake in cortical neurons and familial PD patient fibroblasts by upregulating MCU levels (Verma et al., 2017).

LRRK2 also targets the major presynaptic Ca influx pathway, the CaV2.1 channel, as a further mechanism to modulate intracellular calcium homeostasis. One study shows that LRRK2 stimulates CaV2.1 channels, resulting in an increase in Ca2+ current density (Bedford et al., 2016). Thus, targeting Ca2+ pathways that ultimately converge on mitochondria may represent attractive loci for early therapeutic intervention in PD (Guzman et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2018; Verma et al., 2017).

6. Concluding Remarks

LRRK2 pathogenic mutants are known to cause autosomal dominant PD. Research in the last 15 years has confirmed that pathogenic LRRK2 mutations cause mitochondrial dysfunction in a diverse range of experimental models including C. elegans, Drosophila, rodent brain tissues and primary cultures, human neuroblastoma cell lines, iPSC-derived neurons from PD patient, and PD patient brain tissues (Table 1). It is now generally accepted that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a significant role in the etiology and pathogenesis of PD. However, to date, most of the studies relating LRRK2 to mitochondria dysfunction are correlative or performed in vitro. Thus, in vivo studies are required to validate these findings and to reveal the physiological relevance.

There are many questions that need to be explored in the future. To begin with, how does LRRK2 affect mitochondria? Is it a direct effect or an indirect effect through interacting with the microtubules thus affecting trafficking? Both mitochondria and lysosomes are affected by LRRK2 mutants, but it is still unclear in which organelles the damage starts and how it is then extended to affect the others. Does impaired autophagic-lysosomal pathway associated with LRRK2 mutations cause the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria; or does mitochondrial damage induced by LRRK2 mutations impact lysosomal function and biogenesis? What stimulates the interaction of LRRK2 with DRP1? How does LRRK2 affect MCU? Although recent studies have found a subset of Rab GTPases as LRRK2 substrates (Dodson et al., 2012; Steger et al., 2016), a continuing search for LRRK2 substrates and interactors, and associated downstream signaling pathways is of critical importance to address these key questions. Finally, it is important to justify whether the observed LRRK2 mutant phenotype is attributed to increased kinase activity or GTPase activity.

To conclude, extensive research is warranted to pinpoint the specific roles of LRRK2 mutants in causing neurodegeneration via mitochondrial dysfunction. It remains to be fully clarified whether mitochondrial dysfunction represents a cause or a consequence of disease pathogenesis.

Highlights.

Pathogenic LRRK2 mutations cause dopaminergic neurodegeneration

Mitochondrial dysfunction is central to Parkinson's disease (PD) pathogenesis

LRRK2 regulates cell survival and oxidative stress

LRRK2 mutations affect mitochondrial dynamics, trafficking, and mitophagy

Acknowledgements/Conflict of interest disclosure

We thank Dr. Bin Gou for his critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (NS098393 to H.Z.). The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Angeles DC, Ho P, Chua LL, Wang C, Yap YW, Ng C, Zhou Z, Lim KL, Wszolek ZK, Wang HY, Tan EK, 2014. Thiol peroxidases ameliorate LRRK2 mutant-induced mitochondrial and dopaminergic neuronal degeneration in Drosophila. Hum Mol Genet. 23, 3157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azkona G, Lopez de Maturana R, Del Rio P, Sousa A, Vazquez N, Zubiarrain A, Jimenez-Blasco D, Bolanos JP, Morales B, Auburger G, Arbelo JM, Sanchez-Pernaute R, 2016. LRRK2 Expression Is Deregulated in Fibroblasts and Neurons from Parkinson Patients with Mutations in PINK1. Mol Neurobiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahnassawy L, Nicklas S, Palm T, Menzl I, Birzele F, Gillardon F, Schwamborn JC, 2013. The parkinson's disease-associated LRRK2 mutation R1441G inhibits neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 2487–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloh RH, Schmidt RE, Pestronk A, Milbrandt J, 2007. Altered axonal mitochondrial transport in the pathogenesis of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease from mitofusin 2 mutations. J Neurosci. 27, 422–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardien S, Lesage S, Brice A, Carr J, 2011. Genetic characteristics of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) associated Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 17, 501–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal MF, 2003. Mitochondria, oxidative damage, and inflammation in Parkinson's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 991, 120–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal MF, 2005. Mitochondria take center stage in aging and neurodegeneration. Ann Neurol. 58, 495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford C, Sears C, Perez-Carrion M, Piccoli G, Condliffe SB, 2016. LRRK2 Regulates Voltage-Gated Calcium Channel Function. Front Mol Neurosci. 9, 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilina A, Rudenko IN, Kaganovich A, Civiero L, Chau H, Kalia SK, Kalia LV, Lobbestael E, Chia R, Ndukwe K, Ding J, Nalls MA, Olszewski M, Hauser DN, Kumaran R, Lozano AM, Baekelandt V, Greene LE, Taymans JM, Greggio E, Cookson MR, 2014. Unbiased screen for interactors of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 supports a common pathway for sporadic and familial Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111, 2626–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger Z, Smith KA, Lavoie MJ, 2010. Membrane localization of LRRK2 is associated with increased formation of the highly active LRRK2 dimer and changes in its phosphorylation. Biochemistry. 49, 5511–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betarbet R, Sherer TB, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov AV, Greenamyre JT, 2000. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci. 3, 1301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindoff L, Birch-Machin M, Cartlidge N, Parker W, Turnbull D, 1989. Mitochondrial function in Parkinson's disease. The Lancet. 334, 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biskup S, Moore DJ, Celsi F, Higashi S, West AB, Andrabi SA, Kurkinen K, Yu SW, Savitt JM, Waldvogel HJ, Faull RL, Emson PC, Torp R, Ottersen OP, Dawson TM, Dawson VL, 2006. Localization of LRRK2 to membranous and vesicular structures in mammalian brain. Ann Neurol. 60, 557–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose A, Beal MF, 2016. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 139 Suppl 1, 216–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caesar M, Zach S, Carlson CB, Brockmann K, Gasser T, Gillardon F, 2013. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 functionally interacts with microtubules and kinase-dependently modulates cell migration. Neurobiol Dis. 54, 280–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cali T, Ottolini D, Brini M, 2014. Calcium signaling in Parkinson's disease. Cell Tissue Res. 357, 439–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, McCaffery JM, Chan DC, 2007. Mitochondrial fusion protects against neurodegeneration in the cerebellum. Cell. 130, 548–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherra SJ 3rd, Steer E, Gusdon AM, Kiselyov K, Chu CT, 2013. Mutant LRRK2 elicits calcium imbalance and depletion of dendritic mitochondria in neurons. Am J Pathol. 182, 474–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti B, Sugama S, Lucero J, Winsky-Sommerer R, Wirz SA, Maher P, Andrews Z, Barr AM, Morale MC, Paneda C, Pemberton J, Gaidarova S, Behrens MM, Beal F, Sanna PP, Horvath T, Bartfai T, 2005. Uncoupling protein 2 protects dopaminergic neurons from acute 1,2,3,6-methyl-phenyl-tetrahydropyridine toxicity. J Neurochem. 93, 493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson MR, 2010. The role of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) in Parkinson's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 11, 791–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson MR, 2016. Cellular functions of LRRK2 implicate vesicular trafficking pathways in Parkinson's disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 44, 1603–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper O, Seo H, Andrabi S, Guardia-Laguarta C, Graziotto J, Sundberg M, McLean JR, Carrillo-Reid L, Xie Z, Osborn T, Hargus G, Deleidi M, Lawson T, Bogetofte H, Perez-Torres E, Clark L, Moskowitz C, Mazzulli J, Chen L, Volpicelli-Daley L, Romero N, Jiang H, Uitti RJ, Huang Z, Opala G, Scarffe LA, Dawson VL, Klein C, Feng J, Ross OA, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Marder K, Surmeier DJ, Wszolek ZK, Przedborski S, Krainc D, Dawson TM, Isacson O, 2012. Pharmacological rescue of mitochondrial deficits in iPSC-derived neural cells from patients with familial Parkinson's disease. Sci Transl Med. 4, 141ra90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Yu M, Niu J, Yue Z, Xu Z, 2011. Expression of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) inhibits the processing of uMtCK to induce cell death in a cell culture model system. Biosci Rep. 31, 429–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W, Przedborski S, 2003. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 39, 889–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J, Lewis PA, Greggio E, Sluch E, Beilina A, Cookson MR, 2008. Structure of the ROC domain from the Parkinson's disease-associated leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 reveals a dimeric GTPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 105, 1499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson MW, Zhang T, Jiang C, Chen S, Guo M, 2012. Roles of the Drosophila LRRK2 homolog in Rab7-dependent lysosomal positioning. Hum Mol Genet. 21, 1350–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusonchet J, Kochubey O, Stafa K, Young SM Jr., Zufferey R, Moore DJ, Schneider BL, Aebischer P, 2011. A rat model of progressive nigral neurodegeneration induced by the Parkinson's disease-associated G2019S mutation in LRRK2. J Neurosci. 31, 907–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egnatchik RA, Leamy AK, Jacobson DA, Shiota M, Young JD, 2014. ER calcium release promotes mitochondrial dysfunction and hepatic cell lipotoxicity in response to palmitate overload. Mol Metab. 3, 544–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteves AR, Gozes I, Cardoso SM, 2014. The rescue of microtubule-dependent traffic recovers mitochondrial function in Parkinson's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1842, 7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteves AR, M GF, Santos D, Januario C, Cardoso SM, 2015. The Upshot of LRRK2 Inhibition to Parkinson's Disease Paradigm. Mol Neurobiol. 52, 1804–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer M, Stone J, Mata IF, Lincoln S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Strain KJ, Maraganore DM, 2005. LRRK2 mutations in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 65, 738–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferree A, Guillily M, Li H, Smith K, Takashima A, Squillace R, Weigele M, Collins JJ, Wolozin B, 2012. Regulation of physiologic actions of LRRK2: focus on autophagy. Neurodegener Dis. 10, 238–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu MM, Holzbaur EL, 2014. Integrated regulation of motor-driven organelle transport by scaffolding proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 24, 564–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi PN, Wang X, Zhu X, Chen SG, Wilson-Delfosse AL, 2008. The Roc domain of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 is sufficient for interaction with microtubules. J Neurosci Res. 86, 1711–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoccaro MP, La Morgia C, Rizzo G, Carelli V, 2017. Mitochondrial DNA and primary mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 32, 346–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilks WP, Abou-Sleiman PM, Gandhi S, Jain S, Singleton A, Lees AJ, Shaw K, Bhatia KP, Bonifati V, Quinn NP, Lynch J, Healy DG, Holton JL, Revesz T, Wood NW, 2005. A common LRRK2 mutation in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 365, 415–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillardon F, 2009. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 phosphorylates brain tubulin-beta isoforms and modulates microtubule stability--a point of convergence in parkinsonian neurodegeneration? J Neurochem. 110, 1514–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godena VK, Brookes-Hocking N, Moller A, Shaw G, Oswald M, Sancho RM, Miller CC, Whitworth AJ, De Vos KJ, 2014. Increasing microtubule acetylation rescues axonal transport and locomotor deficits caused by LRRK2 Roc-COR domain mutations. Nat Commun. 5, 5245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Suaga P, Luzon-Toro B, Churamani D, Zhang L, Bloor-Young D, Patel S, Woodman PG, Churchill GC, Hilfiker S, 2012. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 regulates autophagy through a calcium-dependent pathway involving NAADP. Hum Mol Genet. 21, 511–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosal D, Ross OA, Wiley J, Irvine GB, Johnston JA, Toft M, Mata IF, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Taylor JP, Lincoln SJ, Farrer MJ, Lynch T, Mark Gibson J, 2005. Clinical traits of LRRK2-associated Parkinson's disease in Ireland: a link between familial and idiopathic PD. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 11, 349–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greggio E, Zambrano I, Kaganovich A, Beilina A, Taymans JM, Daniels V, Lewis P, Jain S, Ding J, Syed A, Thomas KJ, Baekelandt V, Cookson MR, 2008. The Parkinson disease-associated leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) is a dimer that undergoes intramolecular autophosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 283, 16906–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald A, Arns B, Meier B, Brockmann K, Tadic V, Klein C, 2014. Does uncoupling protein 2 expression qualify as marker of disease status in LRRK2-associated Parkinson's disease? Antioxid Redox Signal. 20, 1955–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Wokosin D, Kondapalli J, Ilijic E, Schumacker PT, Surmeier DJ, 2010. Oxidant stress evoked by pacemaking in dopaminergic neurons is attenuated by DJ-1. Nature. 468, 696–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, 2010. Genetic analysis of pathways to Parkinson disease. Neuron. 68, 201–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori N, Tanaka M, Ozawa T, Mizuno Y, 1991. Immunohistochemical studies on complexes I, II, III, and IV of mitochondria in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 30, 563–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindle S, Afsari F, Stark M, Middleton CA, Evans GJ, Sweeney ST, Elliott CJ, 2013. Dopaminergic expression of the Parkinsonian gene LRRK2-G2019S leads to non-autonomous visual neurodegeneration, accelerated by increased neural demands for energy. Hum Mol Genet. 22, 2129–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppins S, Lackner L, Nunnari J, 2007. The machines that divide and fuse mitochondria. Annu Rev Biochem. 76, 751–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett EH, Jensen N, Belmonte F, Zafar F, Hu X, Kluss J, Schule B, Kaufman BA, Greenamyre JT, Sanders LH, 2017. LRRK2 G2019S-induced mitochondrial DNA damage is LRRK2 kinase dependent and inhibition restores mtDNA integrity in Parkinson's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 26, 4340–4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CH, Shaltouki A, Gonzalez AE, Bettencourt da Cruz A, Burbulla LF, St Lawrence E, Schule B, Krainc D, Palmer TD, Wang X, 2016. Functional Impairment in Miro Degradation and Mitophagy Is a Shared Feature in Familial and Sporadic Parkinson's Disease. Cell Stem Cell. 19, 709–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iaccarino C, Crosio C, Vitale C, Sanna G, Carri MT, Barone P, 2007. Apoptotic mechanisms in mutant LRRK2-mediated cell death. Hum Mol Genet. 16, 1319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Gehrke S, Wang HQ, Takahashi R, Hasegawa K, Oota E, Lu B, 2008. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP by LRRK2 affects the maintenance of dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila. Embo j. 27, 2432–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen ND, Peng Y, Ho CC, Rideout HJ, Petrey D, Liu P, Dauer WT, 2009. The WD40 domain is required for LRRK2 neurotoxicity. PLoS One. 4, e8463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia LV, Lang AE, 2015. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 386, 896–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kett LR, Boassa D, Ho CC, Rideout HJ, Hu J, Terada M, Ellisman M, Dauer WT, 2012. LRRK2 Parkinson disease mutations enhance its microtubule association. Hum Mol Genet. 21, 890–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen SB, Hanss Z, Kruger R, 2018. The genetic architecture of mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Cell Tissue Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law BM, Spain VA, Leinster VH, Chia R, Beilina A, Cho HJ, Taymans JM, Urban MK, Sancho RM, Blanca Ramirez M, Biskup S, Baekelandt V, Cai H, Cookson MR, Berwick DC, Harvey K, 2014. A direct interaction between leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 and specific beta-tubulin isoforms regulates tubulin acetylation. J Biol Chem. 289, 895–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T, 2009. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 373, 2055–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemasters JJ, Theruvath TP, Zhong Z, Nieminen AL, 2009. Mitochondrial calcium and the permeability transition in cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1787, 1395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu W, Oo TF, Wang L, Tang Y, Jackson-Lewis V, Zhou C, Geghman K, Bogdanov M, Przedborski S, Beal MF, Burke RE, Li C, 2009. Mutant LRRK2(R1441G) BAC transgenic mice recapitulate cardinal features of Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci. 12, 826–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, Tsai PI, Wu RM, Chien CT, 2010. LRRK2 G2019S mutation induces dendrite degeneration through mislocalization and phosphorylation of tau by recruiting autoactivated GSK3ss. J Neurosci. 30, 13138–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Parisiadou L, Gu XL, Wang L, Shim H, Sun L, Xie C, Long CX, Yang WJ, Ding J, Chen ZZ, Gallant PE, Tao-Cheng JH, Rudow G, Troncoso JC, Liu Z, Li Z, Cai H, 2009. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 regulates the progression of neuropathology induced by Parkinson's-disease-related mutant alpha-synuclein. Neuron. 64, 807–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod D, Dowman J, Hammond R, Leete T, Inoue K, Abeliovich A, 2006. The familial Parkinsonism gene LRRK2 regulates neurite process morphology. Neuron. 52, 587–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maday S, Twelvetrees AE, Moughamian AJ, Holzbaur EL, 2014. Axonal transport: cargo-specific mechanisms of motility and regulation. Neuron. 84, 292–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marongiu R, Spencer B, Crews L, Adame A, Patrick C, Trejo M, Dallapiccola B, Valente EM, Masliah E, 2009. Mutant Pink1 induces mitochondrial dysfunction in a neuronal cell model of Parkinson's disease by disturbing calcium flux. J Neurochem. 108, 1561–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melrose HL, Dachsel JC, Behrouz B, Lincoln SJ, Yue M, Hinkle KM, Kent CB, Korvatska E, Taylor JP, Witten L, Liang YQ, Beevers JE, Boules M, Dugger BN, Serna VA, Gaukhman A, Yu X, Castanedes-Casey M, Braithwaite AT, Ogholikhan S, Yu N, Bass D, Tyndall G, Schellenberg GD, Dickson DW, Janus C, Farrer MJ, 2010. Impaired dopaminergic neurotransmission and microtubule-associated protein tau alterations in human LRRK2 transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis. 40, 503–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendivil-Perez M, Velez-Pardo C, Jimenez-Del-Rio M, 2016. Neuroprotective Effect of the LRRK2 Kinase Inhibitor PF-06447475 in Human Nerve-Like Differentiated Cells Exposed to Oxidative Stress Stimuli: Implications for Parkinson's Disease. Neurochem Res. 41, 2675–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortiboys H, Johansen KK, Aasly JO, Bandmann O, 2010. Mitochondrial impairment in patients with Parkinson disease with the G2019S mutation in LRRK2. Neurology. 75, 2017–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalls MA, Pankratz N, Lill CM, Do CB, Hernandez DG, Saad M, DeStefano AL, Kara E, Bras J, Sharma M, Schulte C, Keller MF, Arepalli S, Letson C, Edsall C, Stefansson H, Liu X, Pliner H, Lee JH, Cheng R, Ikram MA, Ioannidis JP, Hadjigeorgiou GM, Bis JC, Martinez M, Perlmutter JS, Goate A, Marder K, Fiske B, Sutherland M, Xiromerisiou G, Myers RH, Clark LN, Stefansson K, Hardy JA, Heutink P, Chen H, Wood NW, Houlden H, Payami H, Brice A, Scott WK, Gasser T, Bertram L, Eriksson N, Foroud T, Singleton AB, 2014. Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson's disease. Nat Genet. 46, 989–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CH, Mok SZ, Koh C, Ouyang X, Fivaz ML, Tan EK, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Yu F, Lim KL, 2009. Parkin protects against LRRK2 G2019S mutant-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 29, 11257–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CH, Basil AH, Hang L, Tan R, Goh KL, O'Neill S, Zhang X, Yu F, Lim KL, 2017. Genetic or pharmacological activation of the Drosophila PGC-1alpha ortholog spargel rescues the disease phenotypes of genetic models of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 55, 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HN, Byers B, Cord B, Shcheglovitov A, Byrne J, Gujar P, Kee K, Schule B, Dolmetsch RE, Langston W, Palmer TD, Pera RR, 2011. LRRK2 mutant iPSC-derived DA neurons demonstrate increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. Cell Stem Cell. 8, 267–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu J, Yu M, Wang C, Xu Z, 2012. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 disturbs mitochondrial dynamics via Dynamin-like protein. J Neurochem. 122, 650–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein SJ, Kuo SH, Tasset I, Arias E, Koga H, Fernandez-Carasa I, Cortes E, Honig LS, Dauer W, Consiglio A, Raya A, Sulzer D, Cuervo AM, 2013. Interplay of LRRK2 with chaperone-mediated autophagy. Nat Neurosci. 16, 394–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacelli C, Giguère N, Bourque M-J, Lévesque M, Slack RS, Trudeau L-É, 2015. Elevated mitochondrial bioenergetics and axonal arborization size are key contributors to the vulnerability of dopamine neurons. Current Biology. 25, 2349–2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paisan-Ruiz C, Jain S, Evans EW, Gilks WP, Simon J, van der Brug M, Lopez de Munain A, Aparicio S, Gil AM, Khan N, Johnson J, Martinez JR, Nicholl D, Carrera IM, Pena AS, de Silva R, Lees A, Marti-Masso JF, Perez-Tur J, Wood NW, Singleton AB, 2004. Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 44, 595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papkovskaia TD, Chau KY, Inesta-Vaquera F, Papkovsky DB, Healy DG, Nishio K, Staddon J, Duchen MR, Hardy J, Schapira AH, Cooper JM, 2012. G2019S leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 causes uncoupling protein-mediated mitochondrial depolarization. Hum Mol Genet. 21, 4201–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisiadou L, Xie C, Cho HJ, Lin X, Gu XL, Long CX, Lobbestael E, Baekelandt V, Taymans JM, Sun L, Cai H, 2009. Phosphorylation of ezrin/radixin/moesin proteins by LRRK2 promotes the rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton in neuronal morphogenesis. J Neurosci. 29, 13971–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patron M, Raffaello A, Granatiero V, Tosatto A, Merli G, De Stefani D, Wright L, Pallafacchina G, Terrin A, Mammucari C, 2013. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU): molecular identity and physiological roles. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 288, 10750–10758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira C, Miguel Martins L, Saraiva L, 2014. LRRK2, but not pathogenic mutants, protects against H2O2 stress depending on mitochondrial function and endocytosis in a yeast model. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1840, 2025–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Carrion M, Pischedda F, Biosa A, Russo I, Straniero L, Civiero L, Guida M, Gloeckner CJ, Ticozzi N, Tiloca C, Mariani C, Pezzoli G, Duga S, Pichler I, Pan L, Landers JE, Greggio E, Hess MW, Goldwurm S, Piccoli G, 2018. The LRRK2 Variant E193K Prevents Mitochondrial Fission Upon MPP+ Treatment by Altering LRRK2 Binding to DRP1. Front Mol Neurosci. 11, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pissadaki EK, Bolam JP, 2013. The energy cost of action potential propagation in dopamine neurons: clues to susceptibility in Parkinson's disease. Front Comput Neurosci. 7, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A, Manzoni C, Cookson MR, Lewis PA, 2018. The LRRK2 signalling system. Cell Tissue Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaello A, Mammucari C, Gherardi G, Rizzuto R, 2016. Calcium at the Center of Cell Signaling: Interplay between Endoplasmic Reticulum, Mitochondria, and Lysosomes. Trends Biochem Sci. 41, 1035–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raha S, Robinson BH, 2000. Mitochondria, oxygen free radicals, disease and ageing. Trends Biochem Sci. 25, 502–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajput A, Dickson DW, Robinson CA, Ross OA, Dachsel JC, Lincoln SJ, Cobb SA, Rajput ML, Farrer MJ, 2006. Parkinsonism, Lrrk2 G2019S, and tau neuropathology. Neurology. 67, 1506–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramonet D, Daher JPL, Lin BM, Stafa K, Kim J, Banerjee R, Westerlund M, Pletnikova O, Glauser L, Yang L, 2011. Dopaminergic neuronal loss, reduced neurite complexity and autophagic abnormalities in transgenic mice expressing G2019S mutant LRRK2. PloS one. 6, e18568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed NA, Cai D, Blasius TL, Jih GT, Meyhofer E, Gaertig J, Verhey KJ, 2006. Microtubule acetylation promotes kinesin-1 binding and transport. Curr Biol. 16, 2166–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt P, Schmid B, Burbulla LF, Schondorf DC, Wagner L, Glatza M, Hoing S, Hargus G, Heck SA, Dhingra A, Wu G, Muller S, Brockmann K, Kluba T, Maisel M, Kruger R, Berg D, Tsytsyura Y, Thiel CS, Psathaki OE, Klingauf J, Kuhlmann T, Klewin M, Muller H, Gasser T, Scholer HR, Sterneckert J, 2013. Genetic correction of a LRRK2 mutation in human iPSCs links parkinsonian neurodegeneration to ERK-dependent changes in gene expression. Cell Stem Cell. 12, 354–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosen DA, Cookson MR, 2016. LRRK2 at the interface of autophagosomes, endosomes and lysosomes. Mol Neurodegener. 11, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross OA, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Heckman MG, Aasly JO, Abahuni N, Annesi G, Bacon JA, Bardien S, Bozi M, Brice A, Brighina L, Van Broeckhoven C, Carr J, Chartier-Harlin MC, Dardiotis E, Dickson DW, Diehl NN, Elbaz A, Ferrarese C, Ferraris A, Fiske B, Gibson JM, Gibson R, Hadjigeorgiou GM, Hattori N, Ioannidis JP, Jasinska-Myga B, Jeon BS, Kim YJ, Klein C, Kruger R, Kyratzi E, Lesage S, Lin CH, Lynch T, Maraganore DM, Mellick GD, Mutez E, Nilsson C, Opala G, Park SS, Puschmann A, Quattrone A, Sharma M, Silburn PA, Sohn YH, Stefanis L, Tadic V, Theuns J, Tomiyama H, Uitti RJ, Valente EM, van de Loo S, Vassilatis DK, Vilarino-Guell C, White LR, Wirdefeldt K, Wszolek ZK, Wu RM, Farrer MJ, Genetic Epidemiology Of Parkinson's Disease, C., 2011. Association of LRRK2 exonic variants with susceptibility to Parkinson's disease: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 10, 898–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez-Atienzar S, Bonet-Ponce L, Blesa JR, Romero FJ, Murphy MP, Jordan J, Galindo MF, 2014. The LRRK2 inhibitor GSK2578215A induces protective autophagy in SH-SY5Y cells: involvement of Drp-1-mediated mitochondrial fission and mitochondrial-derived ROS signaling. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Guillily MD, Ferree A, Lanceta J, Chan D, Ghosh J, Hsu CH, Segal L, Raghavan K, Matsumoto K, Hisamoto N, Kuwahara T, Iwatsubo T, Moore L, Goldstein L, Cookson M, Wolozin B, 2009. LRRK2 modulates vulnerability to mitochondrial dysfunction in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 29, 9210–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Ash PE, Gowda V, Liu L, Shirihai O, Wolozin B, 2015. Mutations in LRRK2 potentiate age-related impairment of autophagic flux. Mol Neurodegener. 10, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samann J, Hegermann J, von Gromoff E, Eimer S, Baumeister R, Schmidt E, 2009. Caenorhabditits elegans LRK-1 and PINK-1 act antagonistically in stress response and neurite outgrowth. J Biol Chem. 284, 16482–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LH, Laganiere J, Cooper O, Mak SK, Vu BJ, Huang YA, Paschon DE, Vangipuram M, Sundararajan R, Urnov FD, Langston JW, Gregory PD, Zhang HS, Greenamyre JT, Isacson O, Schule B, 2014. LRRK2 mutations cause mitochondrial DNA damage in iPSC-derived neural cells from Parkinson's disease patients: reversal by gene correction. Neurobiol Dis. 62, 381–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapansky J, Nardozzi JD, Felizia F, LaVoie MJ, 2014. Membrane recruitment of endogenous LRRK2 precedes its potent regulation of autophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 23, 4201–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira AH, Cooper JM, Dexter D, Clark JB, Jenner P, Marsden CD, 1990. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 54, 823–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab AJ, Ebert AD, 2015. Neurite aggregation and calcium dysfunction in iPSC-derived sensory neurons with Parkinson's disease-related LRRK2 G2019S mutation. Stem cell reports. 5, 1039–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab AJ, Sison SL, Meade MR, Broniowska KA, Corbett JA, Ebert AD, 2017. Decreased Sirtuin Deacetylase Activity in LRRK2 G2019S iPSC-Derived Dopaminergic Neurons. Stem Cell Reports. 9, 1839–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S, Webber PJ, West AB, 2009. Dependence of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) kinase activity on dimerization. J Biol Chem. 284, 36346–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Verma P, Raju A, Mohanakumar KP, 2018. Nimodipine attenuates the parkinsonian neurotoxin, MPTP-induced changes in the calcium binding proteins, calpain and calbindin. J Chem Neuroanat. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GA, Jansson J, Rocha EM, Osborn T, Hallett PJ, Isacson O, 2016. Fibroblast Biomarkers of Sporadic Parkinson's Disease and LRRK2 Kinase Inhibition. Mol Neurobiol. 53, 5161–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WW, Pei Z, Jiang H, Moore DJ, Liang Y, West AB, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Ross CA, 2005. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) interacts with parkin, and mutant LRRK2 induces neuronal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102, 18676–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soman S, Keatinge M, Moein M, Da Costa M, Mortiboys H, Skupin A, Sugunan S, Bazala M, Kuznicki J, Bandmann O, 2017. Inhibition of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter rescues dopaminergic neurons in pink1(-/-) zebrafish. Eur J Neurosci. 45, 528–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafa K, Tsika E, Moser R, Musso A, Glauser L, Jones A, Biskup S, Xiong Y, Bandopadhyay R, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Moore DJ, 2014. Functional interaction of Parkinson's disease-associated LRRK2 with members of the dynamin GTPase superfamily. Hum Mol Genet. 23, 2055–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger M, Tonelli F, Ito G, Davies P, Trost M, Vetter M, Wachter S, Lorentzen E, Duddy G, Wilson S, Baptista MA, Fiske BK, Fell MJ, Morrow JA, Reith AD, Alessi DR, Mann M, 2016. Phosphoproteomics reveals that Parkinson's disease kinase LRRK2 regulates a subset of Rab GTPases. Elife. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YC, Qi X, 2013. Inhibition of excessive mitochondrial fission reduced aberrant autophagy and neuronal damage caused by LRRK2 G2019S mutation. Hum Mol Genet. 22, 4545–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YC, Guo X, Qi X, 2015. Threonine 56 phosphorylation of Bcl-2 is required for LRRK2 G2019S-induced mitochondrial depolarization and autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1852, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier DJ, Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Schumacker PT, 2011. The role of calcium and mitochondrial oxidant stress in the loss of substantia nigra pars compacta dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience. 198, 221–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tain LS, Mortiboys H, Tao RN, Ziviani E, Bandmann O, Whitworth AJ, 2009. Rapamycin activation of 4E-BP prevents parkinsonian dopaminergic neuron loss. Nat Neurosci. 12, 1129–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taymans JM, Nkiliza A, Chartier-Harlin MC, 2015. Deregulation of protein translation control, a potential game-changing hypothesis for Parkinson's disease pathogenesis. Trends Mol Med. 21, 466–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JM, Li T, Yang W, Xue F, Fishman PS, Smith WW, 2016. 68 and FX2149 Attenuate Mutant LRRK2-R1441C-Induced Neural Transport Impairment. Front Aging Neurosci. 8, 337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y, Giaime E, Yamaguchi H, Ichimura T, Liu Y, Si H, Cai H, Bonventre JV, Shen J, 2012. Loss of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 causes age-dependent bi-phasic alterations of the autophagy pathway. Mol Neurodegener. 7, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ved R, Saha S, Westlund B, Perier C, Burnam L, Sluder A, Hoener M, Rodrigues CM, Alfonso A, Steer C, Liu L, Przedborski S, Wolozin B, 2005. Similar patterns of mitochondrial vulnerability and rescue induced by genetic modification of alpha-synuclein, parkin, and DJ-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 280, 42655–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venderova K, Kabbach G, Abdel-Messih E, Zhang Y, Parks RJ, Imai Y, Gehrke S, Ngsee J, Lavoie MJ, Slack RS, Rao Y, Zhang Z, Lu B, Haque ME, Park DS, 2009. Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2 interacts with Parkin, DJ-1 and PINK-1 in a Drosophila melanogaster model of Parkinson's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 18, 4390–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma M, Callio J, Otero PA, Sekler I, Wills ZP, Chu CT, 2017. Mitochondrial Calcium Dysregulation Contributes to Dendrite Degeneration Mediated by PD/LBD-Associated LRRK2 Mutants. J Neurosci. 37, 11151–11165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vives-Bauza C, Przedborski S, 2011. Mitophagy: the latest problem for Parkinson's disease. Trends Mol Med. 17, 158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Yan MH, Fujioka H, Liu J, Wilson-Delfosse A, Chen SG, Perry G, Casadesus G, Zhu X, 2012. LRRK2 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and function through direct interaction with DLP1. Hum Mol Genet. 21, 1931–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AB, Moore DJ, Biskup S, Bugayenko A, Smith WW, Ross CA, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, 2005. Parkinson's disease-associated mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 augment kinase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102, 16842–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YC, Ysselstein D, Krainc D, 2018. Mitochondria-lysosome contacts regulate mitochondrial fission via RAB7 GTP hydrolysis. Nature. 554, 382–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue M, Hinkle KM, Davies P, Trushina E, Fiesel FC, Christenson TA, Schroeder AS, Zhang L, Bowles E, Behrouz B, Lincoln SJ, Beevers JE, Milnerwood AJ, Kurti A, McLean PJ, Fryer JD, Springer W, Dickson DW, Farrer MJ, Melrose HL, 2015. Progressive dopaminergic alterations and mitochondrial abnormalities in LRRK2 G2019S knock-in mice. Neurobiol Dis. 78, 172–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimprich A, Biskup S, Leitner P, Lichtner P, Farrer M, Lincoln S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Uitti RJ, Calne DB, Stoessl AJ, Pfeiffer RF, Patenge N, Carbajal IC, Vieregge P, Asmus F, Muller-Myhsok B, Dickson DW, Meitinger T, Strom TM, Wszolek ZK, Gasser T, 2004. Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron. 44, 601–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]