Abstract

Background

Most clinical trials evaluating treatments for alcohol use target individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorder (AUD), but few address change in diagnostic status following treatment or as a potential outcome indicator. This study evaluated whether DSM-5 AUD total criteria count or severity category were sensitive to change over time and treatment effects.

Methods

Data were drawn from a randomized clinical trial that evaluated the efficacy of computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy program (CBT4CBT) for AUD. Sixty-eight individuals were randomized to one of three weekly outpatient treatments for an 8-week period: (1) treatment as usual (TAU), (2) TAU+CBT4CBT, and (3) CBT4CBT+brief monitoring. Structured clinical interviews were used to determine current (past 30 days) AUD diagnosis at baseline, end-of-treatment, and 6-months following end-of-treatment. Change in the total number of DSM criteria endorsed, as well as severity categories (mild, moderate, severe), was evaluated across time and by treatment condition.

Results

Generalized poisson linear mixed models revealed a significant reduction in the number of DSM criteria from baseline to treatment endpoint [time effect χ2(1) = 35.54, p<.01], but no significant interactions between time and treatment condition. Fewer total criteria endorsed, as well as achieving at least a 2-level reduction in AUD severity category at end-of-treatment were associated with better outcomes during follow-up. Chi-square results indicated a greater proportion of individuals assigned to TAU+CBT4CBT had at least a 2-level reduction in severity category compared to TAU, at trend-level significance [χ2(2, 54) =5.13, p=.07], consistent with primary alcohol use outcomes in the main trial.

Conclusions

This is the first study to demonstrate change in DSM-5 AUD total criteria count, as well as severity category, in a randomized clinical trial. These findings offer support for their use as a potential clinically meaningful outcome indicator.

Keywords: DSM-5, Alcohol Use Disorder, Criteria Count, Severity Category, Treatment Outcome Indicator

INTRODUCTION

Virtually all clinical trials evaluating behavioral and/or pharmacological treatments for alcohol use include measures of drinking quantity or frequency as a primary outcome indicator. However, alcohol use disorder (AUD) itself is not defined by quantity/frequency measures, but rather by drinking-related aspects of how an individual feels and functions (e.g., impaired control over drinking, giving up important social or occupational activities) (Hasin et al., 2017). The clinical significance of drinking-based outcome measures has been demonstrated by their relationship with improvement in functioning, such as fewer alcohol-related consequences (Falk et al., 2010, Witkiewitz et al., 2017b), lower psychiatric severity (Kline-Simon et al., 2013), and lower healthcare costs (Aldridge et al., 2016, Kline-Simon et al., 2014). Yet very few studies have examined changes in diagnostic status as an outcome.

Epidemiological research has indicated support for a dimensional diagnostic approach to AUD, as compared to a categorical diagnosis, in terms of stronger relationships with risk factors for AUD (Hasin and Beseler, 2009), alcohol treatment (Hasin et al., 2006), and as a predictor of alcohol consumption (Dawson et al., 2010). Nevertheless, DSM-5 retained a categorical approach to AUD diagnosis, using a threshold of criteria endorsed (2 or more of 11) to indicate the presence or absence of the disorder. Although the addition of a tri-categorized severity scale (mild, moderate, severe) was intended to distinguish between levels of AUD, thereby adding a dimensional aspect to the diagnosis, criticism remains regarding its categorical nature (Fazzino et al., 2014b, Fazzino et al., 2014a). While much of the research on DSM-5 criteria has focused on reliability and validity of the diagnosis and severity categories (Hasin et al., 2006, Dawson et al., 2010, Lane and Sher, 2015, Hoffmann and Kopak, 2015, Preuss et al., 2014), there have been few examinations of whether change in criteria count or severity category can be a meaningful outcome for AUD treatment.

In a study evaluating the benefits of alcohol self-monitoring via interactive voice response following a brief intervention for heavy drinkers (defined as exceeding NIAAA guidelines for low-risk drinking in the past 3 months: >2 drinks per day/14 per week for men or >1 drink per day/7 per week for women; or 5+/4+ drinks in a day for men/women) in primary care, Fazzino and colleagues (2014b) used a multi-model inference technique to determine that a fully dimensional measure of AUD was a more accurate predictor of change in weekly alcohol consumption than the DSM-5 tri-categorized severity scale. The dimensional AUD measure was based on a summed total of DSM-IV dependence and abuse criteria (range from 0–11) met in the past 12 months as determined by an interview-based assessment, with the craving criterion for DSM-5 approximated from participant reports after the interview. This is consistent with their earlier report with the same sample, indicating a dimensional definition of AUD was superior for detecting change in alcohol consumption than the DSM-IV categorical approach (Fazzino et al 2014a). These reports suggest that a dimensional approach based on the summation of endorsed AUD criteria might be better for predicting treatment effects than the categorical approach used in DSM-IV and now DSM-5. However, both of these evaluations examined baseline AUD criteria as predictors of treatment effects, not as an outcome of treatment. Repeat assessment of AUD criteria following treatment could provide useful information regarding its utility as a treatment outcome indicator.

In this secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of a web-based treatment for AUD (Kiluk et al., 2016), wherein DSM-5 AUD criteria were assessed at multiple time points, the following questions were addressed: (1) does DSM-5 criteria count and/or severity category change following treatment?, and (2) are DSM-5 criteria counts and/or severity category at the end of treatment associated with severity of alcohol use and other problems during follow-up (i.e., is it clinically meaningful)? We also explored whether changes in meeting diagnostic threshold or criteria counts were sensitive to treatment effects on alcohol use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants were treatment-seeking individuals participating in a randomized controlled trial of CBT4CBT (Kiluk et al., 2016). To be eligible for the RCT, individuals had to be: (1) at least 18 years of age or older, (2) fluent in English with at least a 6th grade reading level, (3) met current (past 30 days) DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, (4) psychiatrically stable for outpatient level of care. Individuals were excluded who either had an untreated bipolar or psychotic disorder, a legal case pending such that incarceration was imminent during the 8-week trial, were seeking alcohol pharmacotherapy, or met DSM-IV criteria for current dependence on another drug other than alcohol.

Eligibility for the trial in terms of DSM criteria was evaluated using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV; First et al., 1995). At the time this trial was conducted, March 2012 – December 2014, the DSM-5 and the accompanying SCID were not yet published. However, through communication with members of the DSM 5 Substance-Related Disorders work group (Hasin et al. 2013), we added a craving criterion question to the SCID-IV enabling use of the AUD criteria planned for DSM-5. The craving criterion was not used for evaluation of alcohol abuse or dependence criteria to determine eligibility for this study.

As described in the main study report (Kiluk et al., 2016), 87 individuals provided written informed consent approved by the Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigations Committee and were screened for eligibility. Of these, 68 were deemed eligible and were randomly assigned to one of three treatment conditions (described below) using an urn randomization program (Stout et al., 1994) designed to balance groups with respect to gender, ethnicity, education level, legal probation status, and severity of alcohol use during the past year as assessed by the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993).

Treatments

The 68 eligible participants were randomly assigned to one of the following treatment conditions delivered over an 8-week period: (1) treatment as usual (TAU), consisting of weekly group and/or individual psychotherapy at the outpatient facility; (2) TAU plus CBT4CBT (TAU+CBT4CBT), consisting of standard weekly treatment in addition to access to the web-based CBT4CBT program (see below); or (3) CBT4CBT plus brief weekly clinical monitoring (CBT4CBT+monitoring), consisting of access to the web-based CBT4CBT program in conjunction with brief (~10 minutes) in-person weekly sessions with a doctoral-level psychologist. These monitoring sessions were manual-guided (Carroll et al., 1998) and intended for the purpose of monitoring participants’ overall functional status and safety, addressing questions or concerns, and reviewing participants’ use of the CBT4CBT program.

Participants assigned to either of the CBT4CBT treatment conditions were provided access to the web-based program on a dedicated computer in a private room within the clinic. Described in greater detail elsewhere (Kiluk et al., 2016, Carroll et al., 2008), the program consists of 7 core CBT skill topics (‘modules’), each taking about 45 minutes to complete, that included videos and interactive exercises to convey key concepts for avoiding alcohol use (e.g., drink refusal, coping with craving).

Assessments

The SCID-IV was administered during participant screening for study eligibility, with one added craving item consistent with DSM-5 criteria. It was re-administered at the end-of-treatment (week 8) and again at the final follow-up interview (week 32). The AUDIT was administered before randomization to measure hazardous drinking levels during the past year (Saunders et al., 1993). The Short Inventory of Problems (SIP; Feinn et al., 2003) was administered at baseline, and at final follow-up to measure the level of negative consequences from alcohol use during the past three months. The Substance Use Calendar, a Timeline FollowBack method (Sobell and Sobell, 1992) was used to collect retrospective day-by-day self-reports of alcohol use during the 28-day period prior to randomization, through the 8-week treatment period, and through the 6-month period following treatment termination. These were used to calculate alcohol outcome measures, such as percent days abstinent, and the percentage of heavy drinking days (with a heavy drinking day defined as ≥ 5 drinks on any given day for males, and ≥ 4 drinks for females). Breathalyzer samples and urine toxicology screens were obtained weekly during treatment and at each follow-up to assess recent alcohol intake and other drug use; there was a high rate of concordance between self-report and results of breathalyzer (99% concordance) and urine toxicology (97% concordance).

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24. The presence of DSM criteria for alcohol use disorder was determined from the SCID and summed to produce a total criteria count for each participant (maximum of 11 total symptoms) at baseline, week 8 (end of treatment) and week 32 (final follow-up). DSM-5 severity categories were established at each time point using the number of AUD criteria endorsed, with 2–3 criteria indicating ‘mild’, 4–5 indicating ‘moderate’, and 6–11 indicating a ‘severe’ disorder (Hasin et al., 2013). Spearman’s rho correlations were used to evaluate the relationship between DSM total criteria counts and other indicators of alcohol use at baseline (AUDIT scores, days of alcohol use, days of heavy drinking, and mean drinks per drinking day out of the past 28 days prior to baseline). ANOVAs were used to evaluate baseline alcohol use differences across DSM-5 severity categories. The frequency of endorsement for each DSM-5 criterion was examined at each time point. Generalized linear mixed models with poisson distribution (to accommodate count data) with an unstructured covariance matrix were used to explore whether total criteria count changed over time from baseline to end-of-treatment, and by treatment assignment with the following contrasts: Contrast 1 = TAU+CBT4CBT vs. TAU; Contrast 2 = CBT4CBT+monitoring vs. TAU. These models use all available data; missing data from SCID was minimal (< 15% of intention to treat sample missing), and there was no differential missingness by treatment assignment. To evaluate sensitivity to treatment effects, findings of criteria count change across treatment assignment were compared with those from the main study report regarding primary alcohol use outcomes (Kiluk et al., 2016). We also examined change in criteria counts from end-of-treatment to the final follow-up interview (week 32) according to treatment assignment using generalized linear mixed models with poisson distribution, with the same contrasts as above. Change in AUD severity category from baseline to end-of-treatment was also evaluated using a dichotomous dependent variable defined as any reduction in severity level (Yes/No), as well as a variable defined as at least a two-level reduction in severity level (Yes/No), which excluded those categorized as having ‘mild’ AUD at baseline due to the inability to reduce two levels. We used Spearman’s rho correlations (and ANOVA) to explore whether DSM criteria count or AUD severity category (or change in severity category) at the end-of-treatment was associated with alcohol outcomes during the 6-month follow-up period (e.g., percentage of days abstinent, percentage of heavy drinking days, SIP total score). Lastly, we explored whether change in AUD severity category from baseline to end-of-treatment was sensitive to treatment effects using chi-square analysis.

RESULTS

Participants

As previously reported (Kiluk et al., 2016), there were no demographic or baseline alcohol use differences across treatment conditions for the 68 randomized participants. The majority of participants were male (65%), African-American (54%), with a mean age of 43. In terms of self-reported alcohol use during the 28 days prior to randomization, participants reported on average 12.5 (SD=8.7) drinking days, 7.8 (SD=7.3) heavy drinking days, and 7.4 (SD=4.9) drinks per drinking day. Average age of first alcohol use was 15.2 (SD=3.7), and participants reported 1.6 (SD=2.7) prior treatments for alcohol use in their lifetime. Mean AUDIT score at baseline was 18.4 (SD=8.4). Drug use other than nicotine during the 28 days prior to randomization was infrequent: marijuana = 1.8 days (SD=5.2); cocaine = 0.6 days (SD=1.8).

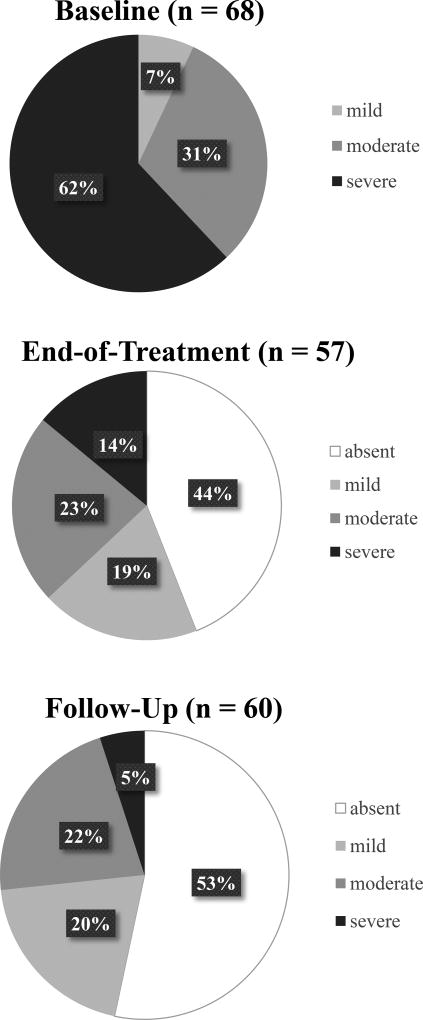

Baseline Criteria Count, Severity, and Alcohol Use Measures

For the full sample (N=68), mean total DSM-5 criteria count at baseline was 6.1 (SD=1.8). Total criteria count did not significantly differ by treatment assignment: TAU Mean=6.5 (SE=.54); TAU+CBT4CBT Mean=5.6 (SE=.50); CBT4CBT+monitoring Mean=6.3 (SE=.51). In terms of DSM-5 severity categories, 42 participants (62%) were classified as having a ‘severe’ alcohol use disorder, 21 (31%) as ‘moderate’, and 5 (7%) as ‘mild’. The proportion of participants in each severity category did not significantly differ by treatment assignment at baseline.

Seven of the 11 criteria for AUD were endorsed by more the half of the participants (see Table 2). The most frequently endorsed criteria at baseline were: drinking alcohol in larger amounts or over a longer period (n=59; 87%); spending a great deal of time in activities necessary to obtain, use, or recover from alcohol (n=58; 85%); a strong desire or urge to use alcohol (i.e., craving) (n=49; 72%); and tolerance to alcohol (n=48; 71%). More than half of the participants endorsed a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down (n=43; 63%), continued use despite a physical or psychological problem caused/exacerbated by alcohol (n=42; 62%), and important social, occupational, or recreational activities given up because of alcohol use (n=40; 59%). Less frequently endorsed criteria included: withdrawal (n=32, 47%), continued use despite social or interpersonal problems caused/exacerbated by alcohol (n=20; 29%), recurrent alcohol use in situations in which it is physically hazardous (n=17; 25%), and recurrent alcohol use resulting in failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home (n=9; 13%).

Table 2.

Percentage of Criteria Endorsement at each Time Point

| % of Endorsement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| DSM-5 Criteria | Baseline (week 0) N = 68 |

End-of-Treatment (week 8) N = 57 |

Final Follow-up (week 32) N = 60 |

| Drinking in larger amounts/longer time | 87 | 30 | 32 |

| Great deal of time to obtain, use, or recover | 85 | 19 | 23 |

| Strong desire or urge (‘craving’) | 72 | 42 | 28 |

| Tolerance | 71 | 19 | 27 |

| Persistent desire/unsuccessful to cut down | 63 | 39 | 30 |

| Use despite physical/psychological problems | 62 | 26 | 10 |

| Important activities given up | 59 | 25 | 12 |

| Withdrawal | 47 | 18 | 5 |

| Use despite social/interpersonal problems | 29 | 21 | 13 |

| Recurrent use in hazardous situations | 25 | 11 | 8 |

| Failure to fulfill role obligations | 13 | 9 | 8 |

| Total criteria endorsed, Mean (SD) | 6.1 (1.8) | 2.6 (2.6) | 2.0 (2.1) |

Results of correlations indicated significant relationships between total criteria counts and several measures of alcohol use severity at baseline, such as, AUDIT total scores (r=.34, p<.01), SIP scores (r=.34, p<.01), years of alcohol use (r=.26, p=.03), and trend significance for the mean number of drinks per drinking day (r=.22, p=.07). However, total criteria counts were not significantly correlated with the mean number of days of alcohol use (r=−.05, p=.68), or the mean number of heavy drinking days during the 28-day period prior to randomization (r=.16, p=.20). Results of ANOVAs indicated significant differences across DSM severity categories on several measures of alcohol use severity at baseline (displayed in Table 1). Participants categorized as ‘severe’ reported a greater number of years of alcohol use [F(2,65) = 3.23, p = .05], had a significantly higher AUDIT score [F(2,65) = 5.25, p < .01], as well as a higher SIP score [F(2,65) = 4.39, p < .05] than those in the less severe categories. There was a linear increase in the mean number of drinks per drinking day from ‘mild’ to ‘moderate’ to ‘severe’ categories, although these differences did not reach statistical significance (p=.09). However, we discovered an extreme outlier in the ‘mild’ severity category; one participant reported 28 heavy drinking days and considerably higher AUDIT and SIP scores (28 and 24, respectively) compared to others in the ‘mild’ category. After excluding this participant, mean baseline alcohol use measures for those in the ‘mild’ category (n=4) were as follows: days of alcohol use (M=12; SD=12.3); number of drinks per drinking day (M=3.2; SD=1); number of heavy drinking days (M=3.5; SD=6.4); AUDIT (M=11; SD=6.4); years of alcohol use (M=5.5; SD=4.7); SIP (M=6.5; SD=5). The number of drinking days, heavy drinking days, AUDIT, and SIP scores were now lowest for those in the ‘mild’ category. Also in separate analyses, results indicated a significant correlation between AUD criteria count and mean number of heavy drinking days (r=.25, p=.04), as well as trend-level significance across DSM severity category on mean number of heavy drinking days [F(2,64) = 2.97, p=.06].

Table 1.

Baseline alcohol use measures according to DSM-5 AUD severity level

| Mild (n = 5)* |

Moderate (n = 21) |

Severe (n = 42) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline alcohol use measure | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F | p |

| Days of alcohol use past 28 | 15.2 | 12.8 | 12.1 | 8.5 | 12.4 | 8.5 | 0.26 | .78 |

| Number of drinks per drinking day past 28 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 6.4 | 4.5 | 8.3 | 5.2 | 2.48 | .09 |

| Number of heavy drinking days past 28 | 8.4 | 12.3 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 9.0 | 7.2 | 1.97 | .15 |

| AUDIT Score | 14.4 | 9.4 | 14.6 | 6.0 | 21.0 | 8.5 | 5.25 | <.01 |

| Years of alcohol use (lifetime) | 6.4 | 4.5 | 12.3 | 11.9 | 17.2 | 10.4 | 3.23 | .05 |

| SIP Score | 10.0 | 8.9 | 10.1 | 8.9 | 18.5 | 11.6 | 4.39 | .02 |

|

| ||||||||

| DSM AUD criteria | 2.8 | 0.4 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 7.3 | 1.1 | ||

Note: df = (2,65) for all F tests except SIP score, which is (2,60)

One extreme outlier identified in the mild AUD severity category. When outlier was excluded, mean baseline alcohol use measures for those in the mild category (n=4) were as follows: Days of alcohol use (M=12; SD=12.3); Number of drinks per drinking day (M=3.2; SD=1); Number of heavy drinking days (M=3.5; SD=6.4); AUDIT (M=11; SD=6.4); Years of alcohol use (M=5.5; SD=4.7); SIP (M=6.5; SD=5).

Change in Criteria Count, Severity Over Time

In terms of data availability to evaluate change over time, 57 participants completed the SCID at end-of-treatment, and 60 completed at the final follow-up (84% and 88% of the intention to treat sample, respectively). Results of the generalized poisson linear mixed model evaluating change in total criteria count from baseline to end-of-treatment (i.e., week 0 to week 8) indicated a significant effect of time [χ2(1) = 35.54, p<.01], suggesting a decrease in AUD criteria for the sample as a whole. However, results of the time × treatment contrast interactions were not significant for either Contrast 1 or 2. There was not significant change in criteria count from end-of-treatment to the final follow-up interview (i.e., from week 8 to week 32), [χ2(1) = 2.35, p=.13] nor were there significant differences in treatment condition by time. Finally, the change from baseline to the final follow-up was significant, showing a decrease in the number of DSM criteria over the entire study period [χ2 (1) = 59.2, p<.01], yet no treatment by time effects.

The percentage of participants endorsing each of the 11 criteria for AUD at baseline, end-of-treatment, and follow-up are displayed in Table 2. The most frequently endorsed criteria at end-of-treatment were: craving (n=24; 42%), and a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down (n=22; 39%). The criteria with the largest reduction in the percentage of endorsement from baseline to end-of-treatment were: drinking alcohol in larger amounts or over a longer period (from 87% to 30% endorsement); spending a great deal of time in activities necessary to obtain, use, or recover from alcohol (from 85% to 19% endorsement); and tolerance to alcohol (from 71% to 19% endorsement). Similar to end-of-treatment, the most frequently endorsed criteria at final follow-up were: drinking alcohol in larger amounts or over a longer period (n=19; 32%); persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down (n=18; 30%); and craving (n=17; 28%).

In terms of change in severity category, the percentage of participants categorized as ‘mild’, ‘moderate’, and ‘severe’ AUD at baseline, end-of-treatment, and final follow-up interview are displayed in Figure 1. Of the 57 participants who completed the SCID at end-of-treatment, the vast majority achieved at least a 1-level reduction in severity compared to baseline (n=45; 79%), and half achieved at least a 2-level reduction (n=27; 50%) excluding those who were ‘mild’ at baseline. For instance, of the 36 participants categorized as having a ‘severe’ AUD at baseline, only 6 (17%) remained in the severe category at end-of-treatment; 10 (28%) reduced to a ‘moderate’ severity level; 3 (8%) reduced to a ‘mild’ severity; and 17 (47%) no longer met criteria for AUD. Of the 18 participants meeting criteria for a ‘moderate’ severity AUD at baseline, 2 (11%) increased to a severe category at end-of-treatment; 2 (11%) remained at a moderate severity; 7 (39%) reduced to a mild severity; and 7 (39%) no longer met criteria for AUD.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Participants in Each AUD Severity Category at Each Time Point

From end-of-treatment to final follow-up, 39% achieved at least a 1-level reduction in severity category. Comparing severity categories from end-of-treatment to final follow-up, 63% of those meeting criteria for a ‘severe’ AUD at end-of-treatment no longer met criteria for AUD at final follow-up; 75% of those with a ‘moderate’ severity AUD at end-of-treatment reduced to either mild severity or no AUD diagnosis; 70% of those with ‘mild’ severity at end-of-treatment remained at mild or no longer met criteria for AUD; and 67% of those who no longer met criteria for AUD at end-of-treatment remained that way at final follow-up.

The result of chi-square analysis exploring differences in the percentage of participants who demonstrated any reduction in severity category from baseline to end-of-treatment according to treatment assignment was not significant [χ2 (2,57) = 1.08, p=.58]. When the percentage of participants achieving at least a 2-level reduction in severity category was explored (excluding those categorized as ‘mild’ severity at baseline, n=5), results indicated differences at a trend level according to treatment assignment between baseline and end-of-treatment [χ2 (2,54) = 5.13, p = .07]. A greater percentage of those assigned to TAU+CBT4CBT achieved at least a 2-level reduction in AUD severity category (73%), compared to TAU (33%) or CBT4CBT+monitoring (48%).

End-of-Treatment Criteria Count, Severity Category, and Follow-up Outcomes

Results of correlations indicated strong associations between end-of-treatment criteria count and alcohol use outcomes during the 6-month follow-up period. Criteria counts were strongly associated with the percentage of days abstinent during the follow-up period (r = −.47, p<.001), as well as the percentage of heavy drinking days during follow-up (r = .55, p<.001), indicating a greater number of criteria present at end-of-treatment was associated with fewer days of alcohol abstinence and more heavy drinking during follow-up. Correlations also indicated a strong association between end-of-treatment criteria count and total scores on the SIP at final follow-up (r = .39, p<.01), indicating a higher number of endorsed criteria at end-of-treatment were associated with more negative consequences from alcohol during follow-up.

In terms of follow-up outcomes by severity category, results of ANOVA indicated the percentage of days abstinent and the percentage of heavy drinking days during the 6-month follow-up period significantly differed according to end-of-treatment AUD severity category [F(3,49) = 5.95, p<.01, and F(3,49) = 3.94, p<.01, respectively]. Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons indicated participants not meeting AUD criteria at end-of-treatment (‘absent’) had a significantly greater percentage of days abstinent and fewer heavy drinking days than those categorized as ‘moderate’ AUD severity. Also, total scores on the SIP at 6-month follow-up differed according to end-of-treatment AUD severity [F(3,47) = 4.35, p<.01], with post-hoc comparisons indicating those not meeting AUD threshold at end-of-treatment reported significantly fewer negative consequences during follow-up than those categorized as ‘severe’ AUD severity.

Differences on alcohol use outcomes during the follow-up period were also present according to whether participants achieved at least a 2-level reduction in AUD severity category at end-of-treatment. Results of ANOVAs indicated those achieving at least a 2-level reduction at end-of-treatment had a greater percentage of days abstinent during the 6-month follow-up period compared to those not achieving a 2-level reduction (90% vs. 69% days abstinent, respectively; F(1, 49) = 13.07, p<.01). Also, those achieving at least a 2-level reduction had a lower percentage of heavy drinking days during follow-up (5% vs. 16%; F(1,49) = 7.75, p<.01), and a lower total SIP score at final follow-up (7.2 vs. 13.4; F(1,48) = 4.09, p<.05) compared to those not achieving a 2-level reduction at end-of-treatment.

DISCUSSION

This study was the first to evaluate change in the number of DSM-5 criteria for AUD, as well as change in severity category, from baseline to end-of-treatment in a randomized clinical trial. The main findings were as follows: (1) DSM criteria counts and severity categories were associated with multiple indices of heavier alcohol use and problems at baseline, supporting criterion validity of the DSM-5 AUD diagnosis; (2) total criteria counts reduced from baseline to end-of-treatment and follow-up across all three treatment conditions, indicating sensitivity to change over time, and consistent with alcohol use outcomes reported in the main trial (Kiluk et al., 2016); (3) AUD severity category also reduced from baseline to end-of-treatment, with a trend-level effect indicating a greater percentage of those assigned to TAU+CBT4CBT achieved at least a 2-level reduction compared to the other treatment conditions, and (4) criteria counts and severity category at the end of treatment were strongly associated with alcohol outcomes during follow-up, such that higher criteria counts and greater severity were associated with less abstinence, more heavy drinking, and more negative consequences during follow-up. Overall, these findings offer support for the use of DSM-5 AUD total criteria counts (and severity category) as a potential meaningful outcome indicator for clinical trials evaluating treatments for alcohol use.

These results are some of the first to support a dimensional AUD diagnostic approach, based on the count of total AUD criteria endorsed, as a meaningful treatment outcome. Fewer criteria endorsed at the end-of-treatment were reflective of a less negative impact of alcohol use on an individual’s daily life, such as spending less time in activities necessary to obtain, use, or recover from alcohol, as well as not giving up social, occupational, or recreational activities because of alcohol use. Furthermore, end-of-treatment criteria counts were associated with better alcohol outcomes following treatment, including more days abstinent and fewer negative consequences (as measured by SIP). However, these data did not offer evidence that change in DSM 5 criteria counts were sensitive to effects of treatment condition. There was no differential change in criteria count according to treatment assignment, although primary outcomes from the parent trial indicated a greater increase in alcohol abstinence and fewer heavy drinking days for those assigned to TAU+CBT4CBT compared to TAU only (Kiluk et al., 2016).

Our findings do suggest potential value of the tri-categorized DSM-5 AUD severity scale as an indicator of treatment benefit. Although those not meeting the diagnostic threshold for AUD (fewer than 2 symptoms endorsed) at the end-of-treatment had the best outcomes during follow-up, they were not significantly different from those with ‘mild’ severity AUD in terms of alcohol abstinence, heavy drinking, or negative consequences. Furthermore, a greater percentage (at trend level) of those assigned to TAU+CBT4CBT demonstrated a 2-level reduction in severity category from baseline to end-of-treatment, parallel to the primary outcome analyses regarding changes in alcohol use. This 2-level reduction in severity category (e.g., from ‘severe’ to ‘mild’), may be clinically meaningful as it was associated with greater alcohol abstinence, fewer heavy drinking days, and fewer negative consequences from alcohol during a 6-month follow-up period. These severity category reduction indicators were not particularly valuable when evaluating change during a long-term follow-up, likely reflecting a floor effect, as most participants (63%) had either a ‘mild’ severity or did not meet diagnostic threshold for AUD at end-of-treatment. Nevertheless, a reduction in severity category, particularly for those achieving at least a 2-level reduction, may be a meaningful endpoint for clinical trials. This is consistent with the recent work indicating benefits of a reduction in the WHO drinking risk categories (Hasin et al., 2017, Witkiewitz et al., 2017a). It should be noted the WHO drinking risk categories are considered a surrogate measure of an individual’s level of functioning, as they are based solely on total alcohol consumption per day. The DSM 5 AUD severity categories are a more direct measure of an individual’s functioning with respect to alcohol-related problems, with reductions in severity category potentially being meaningful regardless of level of alcohol consumption.

There may be several benefits of using DSM 5 AUD criteria and severity categories as indicators of treatment outcome, relative to other measures of alcohol use or problem severity. According to the US Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) guidance for the selection of endpoints in clinical trials, treatment benefit is demonstrated by an effect on how a patient survives, feels, or functions (Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, 2009). Therefore, determining the effectiveness of a given treatment in terms of the proportion of individuals no longer meeting criteria for the disorder (i.e., ‘remission’) may confer a more meaningful and interpretable indication of treatment benefit than a change in the quantity or frequency of a specified behavior (e.g., alcohol/drug use). This type of outcome should be assessed more regularly in AUD treatment trials. The main drawback is the loss of power to detect significant effects as compared continuous outcomes based on frequency/quantity of alcohol use. The evaluation of change in the severity of the disorder, either through reduction in the number of disorder criteria or categorical severity (with multiple levels) may somewhat mitigate the loss in power. Given that AUD is not defined by the quantity or frequency of alcohol use, and the lack of significant correlations between AUD criteria counts and days of alcohol use (and heavy drinking days) found here, alcohol use measures should not be considered the only estimates of improvement after treatment. While other measures of alcohol problem severity, such as the AUDIT or SIP, could be useful as indicators of treatment improvement, they have limitations as well. For one, the AUDIT was designed and has been evaluated as an instrument for screening rather than treatment outcome (Reinert and Allen, 2007); it also measures drinking behavior in addition to adverse consequences. The SIP on the other hand, measures the recent consequences of drinking and is distinct from alcohol consumption (Feinn et al., 2003), however it does not measure other constructs that define AUD, such as compulsive use, tolerance and withdrawal. Also, both the AUDIT and SIP are self-report instruments that, although offer advantages in terms of administration compared to an interview-based assessment like the SCID, require a level of insight and acknowledgement of consequences that may be limited in those who are reluctant to acknowledge a causal link with alcohol use.

While these findings supporting DSM 5 criteria counts and severity category reduction as meaningful outcomes are promising, there are several limitations. First and foremost, these data originate from a small clinical trial with fewer than 25 participants per treatment condition, limiting the power to detect treatment differences. The small sample size also limited analyses regarding AUD severity category, as noted by the effect of an outlier on some of the results. Second, the inclusion criterion for this trial included ‘current’ DSM diagnosis, which was based on the number of criteria endorsed in the past 30 days. This differs from the DSM 5 definition of a ‘current’ AUD based on the presence of criteria over the past 90 days. The past 30-day duration may have artificially inflated the amount of change in criteria, as compared to a 90-day duration. Given the treatment period for this trial was only 8 weeks, a 90-day duration would have resulted in overlap between the baseline and end-of-treatment time points.

Nevertheless, these findings are the first to evaluate and support a change in DSM 5 AUD criteria count and severity category as a potentially meaningful endpoint for clinical trials. This does not diminish the value of other outcomes based on the frequency/quantity of alcohol use, but rather provides a more direct approach toward examining change in how an individual feels and functions as an indicator of treatment benefit. Evidence of criteria count and severity category reduction has the potential to expand the acceptability of non-abstinence based outcome measures, potentially offering a more easily interpretable outcome from a clinical perspective. Moving below the diagnostic threshold for a substance use disorder appears a promising, reasonable, and practical indicator of clinical significance.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support:

This research was supported by grant R01AA024122 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and P50DA09241 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The parent randomized trial from which these data were drawn was registered at: Clinicaltrials.gov - NCT 01615497.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE:

Kathleen M. Carroll, PhD, is a member of CBT4CBT LLC, which makes some versions of CBT4CBT available to qualified clinicians. The alcohol version of CBT4CBT is not yet released for clinical use.

References

- Aldridge AP, Zarkin GA, Dowd WN, Bray JW. The Relationship Between End-of-Treatment Alcohol Use and Subsequent Healthcare Costs: Do Heavy Drinking Days Predict Higher Healthcare Costs? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:1122–8. doi: 10.1111/acer.13054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Babuscio T, Gordon MA, Portnoy GA, Rounsaville BJ. Computer-assisted cognitive-behavioral therapy for addiction. A randomized clinical trial of 'CBT4CBT'. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:881–888. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nuro KF, Rounsaville BJ, Petrakis I. Compliance Enhancement: A Clinician's Manual for Pharmacotherapy Trials in the Addictions. Yale University Psychotherapy Development Center; 1998. Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Center for drug evaluation and research. Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in medical product development to support labelling claims. Silver Spring, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Saha TD, Grant BF. A multidimensional assessment of the validity and utility of alcohol use disorder severity as determined by item response theory models. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107:31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D, Wang XQ, Liu L, Fertig J, Mattson M, Ryan M, Johnson B, Stout R, Litten RZ. Percentage of subjects with no heavy drinking days: Evaluation as an efficacy endpoint for alcoholclinical trials. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:2022–2034. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzino TL, Rose GL, Burt KB, Helzer JE. Comparison of categorical alcohol dependence versus a dimensional measure for predicting weekly alcohol use in heavy drinkers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014a;136:121–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzino TL, Rose GL, Burt KB, Helzer JE. A test of the DSM-5 severity scale for alcohol use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014b;141:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinn R, Tennen H, Kranzler HR. Psychometric properties of the Short Index of Problems as a measure of recent alcohol-related problems. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1436–1441. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000087582.44674.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Patient Edition. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Beseler CL. Dimensionality of lifetime alcohol abuse, dependence and binge drinking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Liu X, Alderson D, Grant BF. DSM-IV alcohol dependence: a categorical or dimensional phenotype? Psychol Med. 2006;36:1695–705. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, O'brien CP, Auriacombe M, Borges G, Bucholz K, Budney A, Compton WM, Crowley T, Ling W, Petry NM, Schuckit M, Grant BF. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:834–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Wall M, Witkiewitz K, Kranzler HR, Falk D, Litten R, Mann K, O'malley SS, Scodes J, Robinson RL, Anton R. Change in non-abstinent WHO drinking risk levels and alcohol dependence: a 3 year follow-up study in the US general population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:469–476. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30130-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann NG, Kopak AM. How well do the DSM-5 alcohol use disorder designations map to the ICD-10 disorders? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:697–701. doi: 10.1111/acer.12685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Devore KA, Buck MB, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Lapaglia DM, Yates BT, Gordon MA, Carroll KM. Randomized Trial of Computerized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Alcohol Use Disorders: Efficacy as a Virtual Stand-Alone and Treatment Add-On Compared with Standard Outpatient Treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:1991–2000. doi: 10.1111/acer.13162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline-Simon AH, Falk DE, Litten RZ, Mertens JR, Fertig J, Ryan M, Weisner CM. Posttreatment low-risk drinking as a predictor of future drinking and problem outcomes among individuals with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37 Suppl 1:E373–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline-Simon AH, Weisner CM, Parthasarathy S, Falk DE, Litten RZ, Mertens JR. Five-year healthcare utilization and costs among lower-risk drinkers following alcohol treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:579–86. doi: 10.1111/acer.12273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane SP, Sher KJ. Limits of Current Approaches to Diagnosis Severity Based on Criterion Counts: An Example with DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder. Clin Psychol Sci. 2015;3:819–835. doi: 10.1177/2167702614553026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss UW, Watzke S, Wurst FM. Dimensionality and stages of severity of DSM-5 criteria in an international sample of alcohol-consuming individuals. Psychol Med. 2014;44:3303–14. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test: an update of research findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:185–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. New Jersey: Humana Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Delboca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;(Supplement 12):70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Hallgren KA, Kranzler HR, Mann KF, Hasin DS, Falk DE, Litten RZ, O'malley SS, Anton RF. Clinical Validation of Reduced Alcohol Consumption After Treatment for Alcohol Dependence Using the World Health Organization Risk Drinking Levels. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017a;41:179–186. doi: 10.1111/acer.13272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Roos CR, Pearson MR, Hallgren KA, Maisto SA, Kirouac M, Forcehimes AA, Wilson AD, Robinson CS, Mccallion E, Tonigan JS, Heather N. How Much Is Too Much? Patterns of Drinking During Alcohol Treatment and Associations With Post-Treatment Outcomes Across Three Alcohol Clinical Trials. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017b;78:59–69. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]